|

Having written only last week about the elements that I believe will sustain theatre over the long haul, I was intrigued to open yesterday’s New York Times and find that film critic Manohla Darghis was lamenting the loss of communal attendance at movies. The coming-together of audience is an intrinsic part of theatre, now and forever, but is no longer an essential part of seeing movies precisely because movies can be replicated and shown on an ever-expanding variety of platforms, which increasingly insure that you can watch whatever you want whenever you want, without leaving the comfort of your sofa. I happen to remain dedicated to seeing movies in movie theatres, however challenging and dispiriting that can be in so many venues. Well, I hear you say, you’re conditioned to going to theatres to see theatre, so you like the same experience for movies. Actually, no. Except when I’m seeing a comedy, when I do enjoy being a part of group merriment, I am not seeking a communal experience at the movies. In fact, I’m delighted when I manage to catch an under-attended showing: I can throw my coat on an extra seat, chomp on Raisinets to my heart’s content and my arteries’ dismay, and be blissfully unbothered by someone behind me kicking my seat every time they cross or uncross their legs. It doesn’t even matter when I’m at the movies with someone else, since I am always so intent on a film that I will accept no conversation around me or including me for the duration of the film. I know that regardless of others surrounding me or a vast sea of empty seats, the movie will be unchanged, since the audience acts upon a projected image no differently than it does upon the printed page. That is to say, not at all. What surprised me about Darghis’ paean to the lost movie audience (and she seemed so bereft I feel I should invite her to the theatre so she can experience a live audience once again) was that it failed to hit upon the single element that makes movies in a theatre such a distinctive experience that cannot achieve equivalence at home, their unique selling proposition, if you will. That element is scale. Movies are a visual medium and the best of them were and are conceived, shot and meant to be shown on a large canvas, figuratively and literally. I’m not talking about 60”-diagonal-plasma-wow-those-insects-look-cool large, I mean stand-in-line-at-New-York’s-Ziegfeld-for-hours-to-see-Star–Wars large. Theatre can offer any story with grand imagination and scope, but only the movies can magnify the players, so that a twitch of an eyebrow can be seen in the very last row of any theatre, so that an embrace is viewed from a distance so close it’s almost as if you’re in it, so that human fury can seem the size of battling redwoods. Let me seemingly digress for a moment. My college roommate Steve, who used to travel on a lot on business, saw a number of movies on airplanes over the years, and came to develop what we call The Inverse Proportion Theory of movie quality. The theorem, which is pretty infallible, is this: A great movie is great on a movie theatre screen, and a bad movie on the same screen is quite bad. But if you change the scale, watching those movies instead, say, on your home TV, or even further reduced on an airplane or your iPod, a funny thing happens. The good movie loses its impact, while the bad movie suddenly becomes, though not good, passable. Think about it: Lawrence of Arabia on a three-inch screen has sequences that would be interminable or impenetrable writ small, and the same goes for 2001: A Space Odyssey, while Happy Madison on the same screen isn’t quite as grating or overbearing as any Adam Sandler film can be at greater than life size. I developed a corollary movie rating system, which folds in the cost-value equation: See in a theatre; in-theatre at the bargain matinee; second-run theatre (where those still exist); rental (now obsolete); cable or Netflix; cable or Netflix if you’re sick; better to sleep. I wrote last week that theatre’s key point of distinction from the other narrative dramatic forms is that it is performed live; in the case of movies, the distinguishing feature is that they can be so big. Audience presence is not in a defining attribute of film, and the diminution of its in-theatre audience is shared with so many formerly public activities as to be endemic to society; the prevalence of “Bowling Alone” came about even before we could bowl with a Wii, as the personal schedule took precedence over the desire to congregate and share most experiences. But since there is no live theatre when you have an empty venue, the stage has been forced to adopt a contrarian, Luddite and life-saving stance against the prevailing sentiment. Had it not been for Ms. Darghis’ essay, it had been my intent to avoid any manner of follow-up to last week’s blog, which incited a variety of interesting comment, both pro and con (among them from Chris Wilkinson; Rob Weinert-Kendt; and 99 Seats). And my point here is not to rehash my prior message, but to brashly offer my prescription for the motion picture industry and particularly their exhibitors, even as the studios themselves seem so resigned to the loss of theatre revenue that they keep shortening the window between theatrical release and home viewing availability. For god’s sake, embrace size and scale. I don’t mean that you should make big, loud movies; I mean that if the movies are conceived and executed in a way that demands they been seen on screens no home theatre can approximate, then people will go to see them in the theatres, where visionary films have triumphed even with the advent of radio, TV and home video, if only you’ll let them. They’re more than commodities to be exploited on multiple platforms, they’re creative enterprises in a commercial setting, and the movie theatre is filmdom’s Broadway, with the added benefit of existing in markets large and small. Home video, regardless of BluRay, SurroundSound, and streaming on demand, is still the bus and truck version of the real thing. I love the movies in a different way than I love theatre, but dare I say it, I love them each in their own way equally. When I see a play that has rapid-fire, short scenes with a literal and linear construction, I wonder why it wasn’t a movie; when I see a great film like The Hurt Locker I know it could have never been realized as well on stage. But just as I feared that theatre was shrinking even more and forcing its creative artists to write to fit a more constrained model, I am flabbergasted that movies may be doing the same, accepting that the paradigm has changed, instead of fighting to sustain its most distinctive features. Don’t let movies get smaller, folks. There’s no need. We’ve already got that. It’s called television. And if someone wants to sit by me at the movie theatre, I’ll move my coat.

This post originally appeared on the American Theatre Wing website. |

It’s The Pictures That Got Small

April 11th, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

Defending the Invalid

April 4th, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

|

A few times in the past week, I have encountered several people who, unprompted, expressed to me their concern for the future of theatre. I am not sure what prompted this confluence of empathy, but I chose primarily to listen to their dissertations on why theatre was in trouble and why they were worried. It immediately bears mentioning that these were well educated, culturally aware people, who no matter where they were from (and I’ve been on both coasts in the past seven days), seemed well informed on the newest theatrical works, although they were perhaps disproportionately basing their information on The New York Times, rather than a range of media outlets, regardless of their location. Because it has been a hectic week, I simply wasn’t up for a sustained debate about the undying nature of the fabulous invalid; cross-country travel has a funny way of putting me into an altered state: anticipatory anxiety over the rigors of travel, the charming experiences that characterize our modern airports, the unfamiliarity of my accommodations, and so my rhetorical engagement was superseded by the specifics of the tasks I had to accomplish. As I return to New York (I am currently 35,000 feet over the Mississippi, I imagine, but a blanket of clouds prevents better geo-location), I realize that I missed opportunities to evangelize for theatre and so, to avoid this problem in the future, even when torpor besets me, I have decided to enumerate the talking points I should have at the ready any time the vitality or validity of theatre in our present day, or future days, presents itself. Perhaps this may prove useful to others as well. 1. Theatre hasn’t always been for everyone, and it’s not reasonable to expect that it should be. There is this unspoken theory that in the days before electronic media, everyone flocked to the theatre constantly. But for every audience member at Shakespeare’s Globe, there were probably five others else where enjoying a good bear-baiting somewhere. That is to say, even when today’s high culture was somewhat less high flown, there was always an even lower common denominator form of entertainment outselling it, but the latter has never seemed to eradicate the former. In fact, we’ve outlasted bear-baiting, so there. We’ve been asked to stow our electronics and fold up our tray tables in preparation for landing, so I’ll leave my list – albeit incomplete and perhaps a bit irreverent – incomplete. That’s actually not so terrible; after all, our “elevator speeches” are often cut short when we reach our destination. I should acknowledge once again that we face economic struggles in our efforts to make theatre, and the realities of a complicated and ever more technologically wondrous society are not necessarily enhancements that will improve the lot of live theatre in the world. I do not believe simply that “if we build it they will come,” nor do I believe that if we applaud at theatre it will, like Tinker Bell, be perpetually brought back to life. But I do believe that in its simplicity, its foundation in the human connection of people telling, of people enacting stories for other groups of people, live and alive, theatre will go on precisely because we cannot be reduced to a series of zeroes and ones, packed for sale at the local warehouse superstore, or streamed into homes. The very things that make theatre hard to sustain are what insure its survival.

This post originally appeared on the American Theatre Wing website. |

Of Critics Passed

March 28th, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

|

Last week, many blogs and tweets commented on what they saw as the oddity, the irony or even the humor of an obituary appearing in The New York Times for Elizabeth Taylor written by a journalist who had passed away almost six years earlier. Many spoke of “the guy who wrote it,” knowing nothing of his background or expertise. “The guy” was Mel Gussow, a longtime Times writer and critic, who had indeed passed away in 2005. “The guy” was also someone I considered a friend and a teacher, and instead of finding it odd to see his byline again, it cheered me, just as it cheered me to see his name atop the obituary for Ellen Stewart not so long ago. I don’t mean to suggest that I valued Mel as a writer of obituaries; he was far more essential as a critic and interviewer. Sadly, due to the internecine politics of The Great Grey Lady, he had been shunted off those posts long before he passed away, although he never retired. He also wrote several extended profiles of theatre artists for The New Yorker; as I recalled one about Bill Irwin recently for some research needed here at The Wing, remembering it quite distinctly, I was stunned to find it had come out while I was in college, before I’d ever met Mel.  Mike Kuchwara Seeing Mel’s name also brought back a more recent passing, one I mourn perhaps even more deeply: the death of Associated Press critic Michael Kuchwara a bit less than a year ago. Mike was an even closer friend; we spoke perhaps twice a week for almost 25 years, we dined together, went to shows together, he attended my wedding in 2006. I felt his absence deeply at last year’s Tony Awards and I know he would have been calling me almost daily, given my forthcoming job transition, with news and gossip about places where I might next be employed. I did not write about these men when they passed on because I didn’t know quite what to say, perhaps I still don’t, but Mel’s byline provokes reveries: of their writing, of our relationships, of what they meant for the American theatre. Save for their complete devotion to theatre, they were quite different. Mel was quiet, even shy, and if you did not know him, you would think him sullen or perhaps even dull. Mike, on the other hand, while never loud or boisterous, was gregarious, especially when talking about theatre. With Mel, you could often wonder why you were doing most of the talking; with Mike, he was so eager to engage that he would often finish your sentences for you. In both, I think this fostered their success at interviews, albeit with differing styles of drawing out their subjects: people opened up to Mike because he was such an enthusiast; people revealed themselves to Mel if for no other reason than to fill the silence in conversation. But Mel was not aloof, nor Mike indiscriminately verbose: Mel, once he knew you, was quite funny and at times wickedly sly; Mike always remembered your interests and wanted to hear about them, even if it meant not talking about theatre for just a little while. I grew to know these men, both senior to me, during my years as a young publicist at Hartford Stage; even after I began my life as what I refer to as “a recovering press agent” 18 years ago, we remained in touch, even though my career only brought me to Manhattan to live in 2003. There’s a benefit to being a regional press representative as opposed to one in New York: whereas in New York you might only chat with a critic for a few moments as you hand them their tickets on a press night, when you’re out of town you have to take charge of their travel, feeding them and insuring the whole affair goes as smoothly as possible. It means convincing them to visit, since no editor compelled them; it means taking them for a good meal before they see the show. Early in my tenure, I used to personally drive them from New York to Hartford, opening up several hours of nothing but time to talk. And that is how friendship evolves. I must admit that part of my affection for these men grew from their willingness to see the work that I was promoting; I owe my early career success to their agreeing to attend Hartford Stage regularly, although Mel had been traveling to the theatre for two decades before I ever set foot there. Nonetheless, their coverage – national coverage – was essential to the theatre and to my reputation there; I appreciated them, but I also enjoyed them. Lest this be nothing but my personal salute to two friends and two critics passed, I want to frame their loss in a broader context, namely the loss they represent for arts journalism and for the American theatre. Mike, though he was never known in the manner of a Frank Rich or a John Simon, may well have been the most widely read theatre journalist in America, and his audience grew every time another arts department downsized. Indeed, in many cases his reviews appeared without a byline, just the simple identifier of “(AP)” at the start of an article. Mel was never nameless, though as a critic he was often known as “the second-string” theatre chronicler at theTimes, an unfortunate shorthand which diminished both his influence and his impact. Between these two men, I cannot imagine how many shows they saw in their abbreviated lifetimes, but since both had loved theatre before they were paid to write about it, I can only imagine that it numbered in the many thousands – and both could recall, in my experience, most anything they’d seen, to my perpetual delight. They also interviewed pretty much anyone of importance in the field for decades, both befriending select artists. Mel, in particular, developed a remarkable circle of intimates; when in Paris, he would meet Samuel Beckett at a café to visit and talk. Oh, to have been at the next table, eavesdropping on the enigmatic author of Godot and the soft-spoken reporter. I truly mean no slight on any reporter or critic as I write this and fail to mention their work, for I think fondly of so many and admire even more. But when we lost Mel and Mike we lost models of what arts reporters and critics could and should be, kind and gentle journalists who always wanted to see the next show and always wanted to enjoy it. Even when they didn’t, they were more interested in pointing out flaws rather than damning artists for their lapses. Fortunately in this electronic age we can locate their reviews online, rather than resorting to laborious microfilm, but we will never regain the compendium of knowledge they amassed and their dexterity in manipulating it for our edification. We are also unlikely to ever experience such ideal matches of writers with outlets: Mel, whose avoidance of the stylistic flourish or easy wisecrack was so suited to “the paper of record”; Mike, who understood that he was writing for his readership and not for himself, and strove to write from everyman’s perspective, never succumbing to cynicism or obscurantism. I worry that their names will quickly fade from memory; Walter Kerr and Brooks Atkinson, their predecessors, have theatres named for them but I doubt such honors are I store for Mike or Mel. Even as I write, I know this is but a footnote of a memorial, so many bits and bytes that will scroll out of sight quickly enough. But in this era of changing and shrinking arts coverage, they are deserving of constant homage, not for being my friends, but for being friends to everyone who cared about theatre from the 60s to today, even if you never had the opportunity to meet them.  Mel Gussow I have regrets that I did not know of Mel’s illness and didn’t get to say goodbye in any fashion, but it was not his nature to publicize such things; I recall our last lunch at Joe Allen, after I had come to the Wing, at which he expressed his good wishes for my success here (although many years earlier he had predicted to one of my friends that by the time I reached 40, he thought I’d be a Hollywood executive, a career path I later explored and rejected). I recall my last conversation with Mike as well, when we discussed what he might do when he retired, a topic I considered premature; two weeks later, I held his hand in the hospital, one day before he died, and I don’t know if he heard the words I whispered to him or not. I attended Mike’s funeral last year and, last month, a memorial benefit for the disease that took him so swiftly; I attended Mel’s memorial only. Fittingly in both cases, the former was at a cabaret, the latter on the stage of a not-for-profit theatre. They all had one thing in common, and that was the paucity of artists and producers in attendance; I don’t know whether that was by design of the organizers or the choice of the individuals not present. I only know that these men had spent their lives consumed with love for the theatre, and I didn’t see much of the theatre paying their respects, which was a shame. I don’t know whether the AP has any of Mike’s writing in a queue somewhere, to emerge when some theatrical figure passes on; it appears that the Times may yet have a few more examples of Mel’s work to share with the world. I hope so, and indeed, when Lanford Wilson passed away just after Miss Taylor, I awaited the publication of Wilson’s Times obituary in the hope that even as I mourned for Lanford, it might give me another opportunity to hear again from Mel, who likely had seen the original productions of every play that Lanford wrote. To my disappointment, another byline appeared. The other night, half in jest, half in fear, a theatre artist I admire asked me to remind him again, “Why do we have critics?” We have them so that theatre, which can never truly be captured, can be chronicled, examined and preserved by those who love it and have the skill and the opportunity to preserve not the moment itself, but its effect. For their gifts at doing so, I will forever miss Mel and Mike, my friends, and key parts of the collective memory of our field.

This post originally appeared on the American Theatre Wing website.

|

Our Generations

March 14th, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

|

I called playwright A.R. Gurney a few months ago to congratulate him on his newest play. This is a call I make with great frequency, because Gurney (known to all since his childhood as “Pete”), is startlingly prolific these days, and unless I’ve seen him at his newest show, I always like to touch base with him and acknowledge my continuing admiration for him and his work. It’s worth noting that in the few months since this particular call, yet another of his plays has already opened in New York. I’ve been doing this for more than 25 years because Pete was the first major artist I got to meet and work with after I graduated college, when I was a press assistant at the Westport Country Playhouse, where his plays were staples each and every summer for years. Professionally, our association encompasses only four shows, two at Westport and two more at Hartford Stage (one a premiere), but we have seen each other with stunning regularity, at his own plays (I recall introducing him to my mother at a benefit of Love Letters starring Jessica Tandy and Hume Cronyn); at the plays of others (coming up the aisle at The Lion King, he lauded it as great fun); and at various events both in Connecticut and in New York. He is, as ever, one of the most gracious and kind men you could ever want to meet, the warm-hearted WASP uncle I never had. “You keep writing them, Pete,” I said, “And I’ll keep going to them.” “I don’t know, Howard,” he replied, “Maybe it’s time to give it a rest. I’m going to be 80, you know.” Horrified at the thought of his output slackening or drawing to a close, I opted for humor. “You know, Pete, somewhere up in Heaven, Horton Foote is frowning on you right now.” “Ah, yes, Horton. He did keep going , didn’t he?” “And so should you,” I replied. “Well, the truth of it is, I keep getting asked to write things, so I guess I should. And I really love working with the kids down at The Flea.” The Flea Theatre has done some half-dozen of Gurney’s less typical works, including his most overtly political plays, including Mrs. Farnworth; Gurney has written pieces specifically for The Flea’s young company, “The Bats.” “What I really love,” he continued, “is that when I’m working with them, age isn’t an issue. We’re just all in it together. I think theatre may be the only place where that happens.” That was an “a-ha” moment for me. I don’t know that Pete realized it, especially since we weren’t face to face, but his casual statement struck me as completely and utterly true. In a society where, if we are to believe the media, everything is focused on what’s new, what’s hip, what will reach the 18 to 25, or perhaps the 25 to 35 age bracket, the act of theatre, the community of theatre, is all embracing and, unlike in so many other places, we are hungry to hear from our veterans, even as we embrace the new. In fact, the elders are among the first to encourage to next generations, and you need only look to how Gurney, or Edward Albee, interact with younger and even aspiring artists to see that the age divide evaporates when theatre is the topic at hand. Look as well to the cascading celebrations of Stephen Sondheim, which despite their near ubiquity, were “hot tickets” in every iteration. Look still again at how many mature playwrights teach, or act as mentors through theatre companies. Perhaps this is an outgrowth of the fleeting nature of theatre itself. Yes, a script remains and survives its author, but productions do not; unlike movies or books, great works of fully realized theatre live on only in memories, and it is our elders who provide us with some connection to what came before, just as succeeding generations replenish the form to the delight of those who preceded them. This is not unique to authors; I believe it permeates our field, in every discipline that makes up theatre. Whether at a post-performance discussion, special symposium, public lecture or through a recorded interview, we all want to hear about “what it was like when” if the speaker is Rosemary Harris, or Manny Azenberg, or Mike Nichols. They are the closest we have to time travel, since in their presence we learn of experiences and artists from 40 and 50 years ago, who themselves may have been old enough to remember back to what they learned from their elders even years before that. I’ve been privileged to travel through time with such marvelous talents as Helen Stenborg and Frances Sternhagen, who one night over dinner began reminiscing about working with the apparently stentorian Helen Hayes at the Ivoryton Playhouse when Frannie and Helen were just starting their careers; with Austin Pendleton, who just told me stories about playing Motel to Zero Mostel’s Tevye in the original Fiddler on the Roof – and I was one of the tens of thousands who would later play Austin’s role, in my case in community theatre. I distinctly recall my frustration when, on interviewing the engaging raconteur John Cullum, I realized that with only 25 minutes left to talk, we had only reached 1965, and that so much of his great work would be given short shrift, meaning my temporal journey would be foreshortened. We often hear talk about “the theatre community” and I’m delighted to report (perhaps as I become more aware of my own age) that it is a community that reveres its elders, and indeed does not put them out to pasture, but looks for every opportunity not only to celebrate them but to put them to work. In what other field would 80-year-old James Earl Jones be able to be signed for his next Broadway role even before his current engagement is through; where else would a collective mourning take place for the all-too-early losses of Natasha Richardson, Lynn Redgrave and Corin Redgrave not only because we are deprived of their work as artists and the sadness for their loved ones, but because we imagine the ties to the storied Redgrave lineage snapping before our eyes, in much too rapid succession. In theatre, writers can write – and be produced; actors can perform; directors can stage; and designers can imagine for as long as they wish and their work will reach and enrich audiences. Artists are less disposable than they seem to be in the film industry, or popular music. For those of us in the audience, the moment of enrichment may be fleeting; for those who collaborate with our senior artists, their encounters both in the act of making theatre or simply visiting together on breaks must be profound, ultimately finding its way back to us in the seats as well. So even as I seek out new experiences with artists like Julianne Nicholson, Rajiv Joseph, Anne Kauffman and Donyale Werle, I will be there applauding for Angela Lansbury if we’re fortunate enough to have her on stage yet again; I will seek out shows designed by the masterful Eugene Lee, who designed the play that changed my life in 1979; I will hope to see yet another show directed by my idol Hal Prince. And I’ll look forward to many more calls and talks with Pete Gurney, be it to congratulate him, or to egg him on.

This post originally appeared on the American Theatre Wing website.

|

A Bad Word

March 7th, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

|

It goes without saying that, as a literature based-discipline, theatre must be very sensitive in its word usage. Certainly playwrights choose their words with care, to insure that we understand not only story, but character, by faithfully following their script. In contrast to what we hear about the movie business, playwrights’ words are sacrosanct in the theatre; they are not altered, production by production, by actors or directors to make either party – or the audience – more comfortable. Words are the road map from which all theatre springs. So now let me pose a hypothesis: what if the word ‘theatre’ is the greatest threat to the very discipline of theatre? Before you begin to parse the last phrase, let me state that I am not seeking to reopen the tiresome “theater vs. theatre” argument that seems to blossom anew every so often. For the purpose of this discussion (and as far as I’m concerned, at any time) the variant spellings are interchangeable, as is ‘teatro’ which I tossed out once during an internet debate in an effort to end a cycle of meaningless debate. So, why do I worry about the word ‘theatre’? I’m concerned that, like so many things that are said in the world, its meaning to the speaker may be profoundly different to those who hear it. And I fear that the word ‘theatre’ — not the act of making it, or the buildings that house it – has connotations we rarely think about. If you happen to use Google News to search on either word (and the ever literal algorithm distinguishes between them), you will of course find a deluge of articles that speak to the act of people collectively gathering to present a dramatic story live for an assembled audience, as well as a steady flow about performance spaces being built, refurbished or razed. But seeded amongst these expected results are the stories that make we wonder about whether ‘theatre’ always means what we want it to mean. I cannot tell you how many articles about government, be it city, state, federal or foreign, constantly cite acts of ‘political theatre.’ In the vast majority of these citings, they refer not to activists engaging in some performance-based activity designed to illustrate a position on an issue. Instead, ‘political theatre’ seems, in its common usage, to refer to political acts, statements and strategies that are merely for show — empty, hollow gestures that serve only to advance an agenda, and are sized up by reporters as cynical acts of attempted manipulation. I also see flare-ups of articles about ‘security theatre,’ in which the more public efforts to address the safety of the populace, such as the work of the Transportation Safety Authority or random bag checks in the New York City subways, are seen merely as sham demonstrations of protection, rather than meaningful steps towards securing the population. But one thing is for certain: whether it’s ‘political theatre’ or ‘security theatre,’ ‘theatre’ is used to denigrate the action taking place, not to elevate it. So when we talk of drawing people to the theatre, or working in the theatre, are we, for the many people who are not attendees, suggesting that what we do is itself a sham, the apotheosis of fakery? Yes, what we do is to engage audiences in an act of collective pretending, but in order to achieve a higher purpose, whether it is to bring them joy or illuminate some truth. But is that possibly understood by those who have either not been exposed to, or do not connect with, the art form so many of us love? If the media and the public accept ‘theatre’ as a pejorative when it is tied to ventures other than the act of making words come alive on stage, is the word becoming barnacled with a negativity that carries over to our own efforts? Let me offer a corollary. One of the words that theatremakers embrace and champion is the word ‘new.’ It is, to us, a word that means many things – not yet of the repertory, encompassing of current style and ideas, unseen by our constituency – but in every case it is worn as a badge of honor by artists, companies and enlightened funders. That we are engaged in the ‘new’ is to blaze a pathway and be part of building the continuum of the stage. Yet I have learned, from both anecdotal and research evidence at multiple theatres in different communities, that most audiences do not hear ‘new’ when we say it. What they hear is ‘risky,’ ‘unproven,’ ‘experimental,’ even ‘avant-garde,’ when all we’re trying to say is that they probably (or in the case of world premieres, certainly) have not seen it before. And when they’re deciding whether to plunk down money in order to enter into the unknown, many will balk. This is why whenever I hear about theatres surveying their audiences to ask what they’d like to see, the answers are invariably titles of plays they’ve seen before and liked. After all, they cannot name plays as yet unwritten, and the casual theatergoer is not going to ask to be subjected to risk, even though those of us on the inside of creative endeavors know that only by risking do we have the potential to achieve great things. Perhaps you find my wordplay on ‘theatre’ and ‘new’ to be merely semantic pedantry; it surely would not be the first time I’ve been accused of such. But as we watch the political arena, the marketing arena and other cauldrons of ‘message,’ I don’t think we should simply overlook the possibility that the very words which we hold so dear may be stumbling blocks to reaching new audiences. Perhaps we should have gotten a message when a decades-old PBS mainstay of high quality drama dropped ‘theatre’ from its name, to be known henceforth as “Masterpiece.” If it is true that theatre audiences, or audiences for any of the arts, are in fact experiencing a diminution of demand, then we may need better words to describe our efforts and to incite others to experience them, lest the work we create and celebrate – that of playwrights, bookwriters, lyricists and composers – go unheard.

This post originally appeared on the American Theatre Wing website. |

Fastball

February 28th, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

|

This past Friday evening, I attended the Waterbury CT Arts Magnet High School’s production of August Wilson’s Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, a production that had been debated, then delayed, and about which I had been fairly vocal in my advocacy. The students acquitted themselves quite admirably, but the real discovery came during the post-performance discussion, which included the entire cast, as well as the actors Eisa Davis and Frankie Faison. The most revelatory comment of the evening did not pertain to the “n-word” controversy that had threatened to shutter the show. Instead, what made me really sit up and think was a comment from one of the students, in response to a general question about how working on the play affected them. “We don’t get material like this every day,” said the young man (whose name I didn’t catch because I was busy relaying the discussion via Twitter). “We’re the MTV generation. We’re bombarded by trash.” I do not know anything about this young student actor, but this was certainly the first time I had heard an inner-city high school student, albeit one at an arts magnet school, make a statement that heretofore had emanated mostly from the mouths and pens of pundits (amateur and professional) older than I am. And in those few words, the universal value of this production was conveyed, moving beyond the focus on a single word that is heard only in passing in the play’s dialogue. As someone whose high school theatre experience ran to Don’t Drink the Water and Bye Bye Birdie, I never had the chance to explore a difficult work. As a once-aspiring actor, I was never challenged to “up my game” on the stage, by taking on a difficult challenger like Wilson or Miller. We read Albee in English class, although shorn of any context that would have truly revealed The Zoo Story to us, but when it came to putting on a show, the material catered to whatever youthful skills we may have had, rather than advancing them. How many high schools not only allow, but push their kids to grapple with great works? Yes, we can make jokes about a 17-year-old Willy or Linda Loman, and it’s highly unlikely that the performers will ever reach the true core of these characters. But by playing against someone greater than themselves, they discover the challenge that is acting, even if the auditorium is not as full as it might have been had Cats been on offer. As for the trash that bombards kids? We are all bombarded by it. As I write, much of America is focused on dresses from the Oscars or watching the sad spectacle of Charlie Sheen’s self-immolation. If this is what is served up for adult consumption as morning news, I truly cannot imagine the messages and media consumed by high schoolers, middle schoolers, even elementary school kids today. And while most thoughtful people perpetually decry the dumbing down of cultural conversation, the debasement of entertainment, we do our youths no favor if we simplify their education, be it in the name of in loco parentis, ticket sales or budgets. What I was pleased to hear on Friday evening is that there are kids who realize the potential effects of what schools and society at large offers them, and they hunger for more. We underestimate the capacity and the appetites of younger minds at their own peril, since not every student goes to an arts high school, not every student is drawn to work by artists like August Wilson (let alone forced to defend its place on school stages in front of a board of education). I do not advocate this type of work because of its potentially problematic language or content, but because of its larger ideas which belong in the classroom, at our dinner tables, and in our daily lives. We cannot allow the simplistic, sound-bite, lowest common denominator offerings that pass for entertainment become the standard, lestIdiocracy become first prescient, then prevalent. Let’s keep firing metaphoric fastballs at students and let them struggle to hit them back, because it is in that struggle in which they learn the most. A final word. During Friday night’s post-show discussion, an older woman stood up and identified herself as someone who had attended the school board meeting at which the fate of Joe Turner was decided, and confessed that she had been opposed to the production but that after seeing the show, she felt differently. “I’m 72 years old,” she said, “And you have taught me – to trust high school students.” And to learn from them. I know I did. * * * Having shared two notes that I tweeted out during Friday evening’s discussion, let me take this opportunity to recount what little I managed to set down for those who follow me on Twitter, typing quickly with my thumbs even as I paid attention to the worthy colloquy. They are unedited, but in chronological order. I hope they speak for themselves.

This post originally appeared on the American Theatre Wing website.

|

A Great Many Plays and Musicals About The Movies

February 22nd, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

You had to know that this was inevitable.

After my Thanksgiving catalogue of 37 Flicks Theatre Lovers Should Know and 13 Docs That Theatre Lovers Should Know, and my New Year’s disgorgement of An Awful Lot of Plays and Musicals About Theatre, it was inevitable that I would close the circle with this blog, enumerating plays which look at the act of moviemaking and the environs of Hollywood.

There is one strong theme that emerges in these plays, which is that the authors see theatre as purer than Hollywood, and indeed that the film industry is a corrupting influence on artists. Although some of the works show great affection for film genres, the actual process by which movies get made gets low marks from playwrights, and it’s up to the viewers or historians to determine whether that perception comes from experience, jealousy or sheer invention. But overall, playwrights don’t seem to regard the business of moviemaking as representative of or conducive to the creation of art (and producers take a particular hit). Hollywood is not much good for your moral fiber either.

There are many shows that are parodies of or homages to particular films or film genres; one need only look to the work of Charles Ludlam and Charles Busch to find countless examples. But they are about the product of Hollywood, rather than moviemaking itself, so save for a handful of broadly encompassing examples, curtain-to-curtain parodies of genre films do not appear on this list.

This list also highlights the fluidity of stories between film and theatre, as once again there are entries that appeared on the earlier lists, having either begun life as a play and then become a movie, or vice versa, as well as plays that present theatre and film in counterpoint to one another within the same script. It’s also worth noting how often the names of George S. Kaufman, Betty Comden and Adolph Green appear in the list; clearly they had a lot to say on the subject of movies.

Please note that I have defined my territory as plays about the movies, not the entire entertainment industry of Hollywood. Consequently, with a few exceptions, plays about the music industry (Buh-bye, Dreamgirls!) and in particular television (Sorry, The Ruby Sunrise! Apologies, The Farnsworth Invention!) don’t appear. Screen adaptations of plays, and vice versa, would be another blog altogether, and that’s been written about plenty of times anyway.

As always, I don’t pretend that this list is so exhaustively researched as to be definitive. Instead, I hope it’s merely the jumping off point for readers to add their own knowledge to the piece by listing other examples in the comments section.

* * *

ADULT EDUCATION by Elaine May It’s by pure alphabetical accident, but how fitting that a singular screenwriter and one-time improv comedy darling chose the stage to send up the porn film industry and landed first on this list. May’s comedy imagines the scenario if a bunch of adult film stars and their director developed artistic pretensions and attempted to make a film of insight and value. Compared to many of the plays discussed below, May’s comedy takes an affectionate view of her characters, rather than simply hitting the fairly easy target that is XXX-filmmaking.

AMAZONS AND THEIR MEN by Jordan Harrison As “Hitler’s filmmaker,” Leni Riefenstahl has been admired for her technical skills and reviled for her collaboration with the Nazi regime, as well as her subsequent disavowals of any political aims of her own. So, referred to only as The Frau, she gets her comeuppance in this imagining of a true-life event, in which she attempts and fails to make a movie about Achilles’ battle with the Amazons, as did Riefenstahl as World War II was breaking out.

ANGEL CITY by Sam Shepard Based on Shepard’s own experiences working on the screenplay of Zabriskie Point for Michelangelo Antonioni, this early work portrays a trio of unlikely screenwriters summoned by reprehensible producers to help salvage a film in a nightmare vision of Hollywood that leads to its destruction.

THE BIG KNIFE by Clifford Odets A film producer blackmails a star, threatening to reveal his role in a drunk driving accident that killed a child, in a drama drawn both from the life of Odets, who had an unhappy screenwriting career, and that of his original leading man and muse, John Garfield. It marked Odets’ return to Broadway after a six-year hiatus; his subsequent work, The Country Girl, was the greater success.

THE BIOGRAPH GIRL book by Warner Brown, music by David Heneker, lyrics by Brown and Heneker The intertwined fortunes of Lillian and Dorothy Gish, Mary Pickford, Adolph Zukor and D.W. Griffith form the core of this British musical that charts the rise and fall of silent films. Though praised for charm and wit, the show doesn’t fail to attend to the racial issues provoked by Griffith’s Birth of a Nation and the financial impact of the movies’ skyrocketing popularity.

BOY MEETS GIRL by Bella and Sam Spewack A madcap farce about two Hollywood screenwriters (possibly modeled on Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur) who are looking to put a new twist into the old formula that gives the show its name, but the most available “girl” is a widow whose bigamist husband has left her with their infant son, Happy, who becomes a major film star.

BRECHT IN HOLLYWOOD devised by Goran Stefanovski Although it promises the story of Brecht’s sojourn in California, that goes unremarked upon in this loose assemblage of Brecht’s work that may be most notable for featuring, in its London premiere production, Vanessa Redgrave in tap shoes.

BRECHT IN L.A. by Rick Mitchell The clash between Brecht’s personal philosophies about life and theatre and the materialistic, populist mindset of the film community form the core of the drama about the noted playwright’s life in California, during which he had trouble finding work, collaborated with Charles Laughton on a stage production of Galileo, and was ultimately called to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The CHARLIE CHAPLIN Shows (Chaplin with book, music and lyrics by Anthony Newley; Chaplin with book by Ernest Kinoy, music by Roger Anderson and lyrics by Lee Goldsmith; Charlie Chaplin Goes to War (aka Chaplin) by Simon Bradbury and Dan Kamin; Limelight aka Behind the Limelight, book by Thomas Meehan, music and lyrics by Christopher Curtis) Certain figures in Hollywood seem to provide endless source material for dramatists and musical writers alike. Charlie Chaplin, perhaps because his movie ouevre is silent while his personal life spoke volumes, has been the subject of numerous stage portrayals. What is remarkable is that with many efforts, only a handful of which are listed, none has become a major success. Perhaps silence is golden.

CITY OF ANGELS book by Larry Gelbart, Music by Cy Coleman, lyrics by David Zippel This structurally ingenious musical toggles between the film noir story of tough guy gumshoe Stone and the Hollywood travails of his creator, screenwriter Stine, battling the usual studio meddling with his work, even as he lives out his fantasy life through the story of Stone.

CITY OF ANGELS book by Larry Gelbart, Music by Cy Coleman, lyrics by David Zippel This structurally ingenious musical toggles between the film noir story of tough guy gumshoe Stone and the Hollywood travails of his creator, screenwriter Stine, battling the usual studio meddling with his work, even as he lives out his fantasy life through the story of Stone.

COMPLETELY HOLLYWOOD (ABRIDGED) by the Reduced Shakespeare Company While parodies of films abound and are largely absent from this list, I would be remiss (and berated by the playwrights) if I did not make mention of this break-neck, ingenious compendium of filmmaking’s 100-plus-year history through condensations 186 great films, ranging alphabetically from Airplane! to The Wrong Man (what, no Zardoz?).

THE CRIPPLE OF INISHMAAN by Martin McDonagh Rooted in the true-life making of Robert Flaherty’s quasi-documentary Man of Aran, set on the poverty stricken Islands off the coast of Ireland, McDonagh’s protagonist in “Cripple Billy” Clavan, who sees the arrival of a film crew in his otherwise stultifying community as a way up and perhaps out.

A DAY IN HOLLYWOOD/A NIGHT IN THE UKRAINE book by Dick Vosburgh, music by Frank Lazarus, lyrics by Vosburgh I certainly can’t skip this light-hearted entertainment romanticizing Hollywood films, which is really two unrelated one-acts, or more accurately, a first-act revue mixing new and classic songs, and a second act Marx Brothers-styled comedy (adapted from Chekhov’s The Bear, no less) with an original score. Tommy Tune’s Broadway staging lifted some ideas he had previously used in the musical DOUBLE FEATURE by Jeffrey Moss, which he had co-directed at the Long Wharf Theatre; that show contrasted the relationships of two present-day couples with the great romances of the silver screen.

A DAY IN HOLLYWOOD/A NIGHT IN THE UKRAINE book by Dick Vosburgh, music by Frank Lazarus, lyrics by Vosburgh I certainly can’t skip this light-hearted entertainment romanticizing Hollywood films, which is really two unrelated one-acts, or more accurately, a first-act revue mixing new and classic songs, and a second act Marx Brothers-styled comedy (adapted from Chekhov’s The Bear, no less) with an original score. Tommy Tune’s Broadway staging lifted some ideas he had previously used in the musical DOUBLE FEATURE by Jeffrey Moss, which he had co-directed at the Long Wharf Theatre; that show contrasted the relationships of two present-day couples with the great romances of the silver screen.

THE DISENCHANTED by Budd Schulberg and Harvey Breit Although it has much more on its mind than just Hollywood, this little-remembered Tony-nominee for Best Play in the early 60s, drawn from Schulberg’s novel, won Jason Robards Jr. a Tony for his portrayal of a dissipated novelist at the end of his failed career in Hollywood, assigned to research a frothy entertainment by observing a college winter carnival, chaperoned by an aspiring screenwriter. Substitute F. Scott Fitzgerald and Schulberg himself for the play’s lead characters and you have a quasi-fictional account of an actual trip the two men took as “research” at the behest of movie execs in Fitzgerald’s final days.

EPIC PROPORTIONS by Larry Coen and David Crane Seen Off-Broadway in 1986 and then again on Broadway in 1999 (with co-writer Crane creating a sitcom you may have heard of called Friends in the interim), this comedy, despite the claim of its title, is an intimate behind the scenes look at the making of a Cecil B. DeMille-type biblical epic devoid of DeMille’s talent or budget.

FADE OUT, FADE IN book by Betty Comden and Adolph Green, music by Jule Styne, lyrics by Comden and Green A chorus girl is accidently chosen to star in a film, which inexplicably gets made before anyone discovers the mistake, at which point the movie is shelved. But when the film is let out of the can for a sneak preview, both it and its unlikely star become successes. This little seen musical ran on the strength of its star, Carol Burnett, although at one point she attempted to depart the production and was forced back in due to her contractual commitment.

FILM IS EVIL, RADIO IS GOOD by Richard Foreman Lest we neglect the avant-garde, theatrical innovator and enigma-generator Foreman lays out his thesis in his title and proceeds with an elliptical debate on the subject, punctuating it in the original production with, paradoxically, a very good film, and letting the audience draw his take on the theatre from the play they’re watching that juxtaposes the other mediums.

FLIGHT Conceived by Steve Pearson, text by Robyn Hunt Drawn from a true story from 100 years ago, the multifaceted story of two young French actresses who take a break from a production of The Seagull (note metaphor) to serve as a flight team in the early days of aviation. Movies enter the picture as Alisse, a documentary filmmaker, chronicles the endeavor.

FORBIDDEN HOLLYWOOD by Gerard Alessandrini Much like his series of Forbidden Broadway shows, Alessandrini’s Hollywood foray was a send up of both movies themselves as well as the business and gossip behind them, using tunes from classic movie musicals.

FOUR DOGS AND A BONE by John Patrick Shanley Moral bankruptcy abounds in Shanley’s satire of filmmaking as two actresses attempt to manipulate a screenwriter for larger roles in a low-budget film, while a take-no-prisoners producer pursues his own agenda. This 1993 comedy follows Shanley’s Oscar-winning hit Moonstruck and his less-successful directing debut with Joe Vs. The Volcano, but predates Congo, which became his last screenplay credit for 13 years.

GENIUSES by Jonathan Reynolds A biting look at Hollywood in general and the runaway production history of Coppola’s Apocalypse Now in particular, Reynolds’ characters belie the play’s title at every turn, from the sadomasochistic art director to the Hemingway-emulating make-up man, to the jaded screenwriter; the only smart person in evidence is the bimbo (and director’s mistress) brought in to doff her clothes gratuitously at one point in the film. Given the enduring legacy of the Coppola film (itself the subject of a documentary by Coppola’s wife, Hearts of Darkness), it’s surprising no one has revived this comedy for a new generation.

GOLDILOCKS book by Walter and Jean Kerr, music by Leroy Anderson, lyrics by Joan Ford and The Kerrs A sharp tongued actress who’s about to forsake the stage for marriage to a fat cat and an egomaniacal producer who latches onto her as his next big screen star battle their way to romance in this little-remembered Broadway musical that featured no less than Elaine Stritch and Don Ameche in the pre-sound era. Just imagine: Elaine Stritch, but no sound…

A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN FILM by Christopher Durang, music by Mel Marvin, lyrics by Durang A mad dash through some 40 years of movie genres, as five classic character types journey through plotlines reminiscent of film staples. At once an homage to and comment on the content of Hollywood product, the show achieved a remarkable “hat trick” premiere, opening in entirely separate productions at Hartford Stage, Arena Stage and the Mark Taper Forum only a few weeks apart from each other.

HOLLYWOOD EXPOSED by Michael Tester Another spoof of Hollywood genres, featuring Friday the 13th, The Ballet; Maria von Trapp endorsing Valium; Elmer Fudd appearing in Singin’ in the Wayne and selections from Dirty Harry Dancing and A Very Brady Exorcist.

HOLLYWOOD PINAFORE, OR THE LAD WHO LOVED A SALARY book and lyrics by George S. Kaufman, music by Sir Arthur Sullivan Debuting on Broadway only a week after Memphis Bound took the same source material, Gilbert and Sullivan’sH.M.S. Pinafore, on a trip to the American south, Kaufman’s version used it as the framework for a Hollywood satire in which a young starlet is promised in marriage to a studio head by her ambitious director father, while she really loves a disgraced screenwriter. It managed on 52 performances in 1945 (16 better than Bound).

HURLYBURLY by David Rabe Think that Hollywood is filled with narcissistic, substance-abusing, morally bankrupt low-lifes focused on their own gratification? Then this is the play for you.

HURLYBURLY by David Rabe Think that Hollywood is filled with narcissistic, substance-abusing, morally bankrupt low-lifes focused on their own gratification? Then this is the play for you.

I OUGHT TO BE IN PICTURES by Neil Simon Listed more for its title than its topic, Simon’s 18th play focused more much on the rapprochement behind a father and his estranged daughter, but it has its share of Hollywood humor thanks to the father’s formerly successful, now blocked, career as a screenwriter.

KISS OF THE SPIDER WOMAN In the darkest of circumstances, a filthy jail in a Latin American country, two political prisoners sustain themselves by escaping from hellish reality into fantasies of the motion pictures, one of the few examples on this list where the movies are lifelines. Available in both play (by original novelist Manuel Puig) and musical (by John Kander, Fred Ebb and Terrence McNally) versions.

LIKE TOTALLY WEIRD by William Mastrosimone Two teenaged delinquents break into the home of a schlock action film producer and proceed to terrorize the man and his girlfriend by recreating scenes from the producer’s own films. A seemingly exploitative play that examines the responsibility of those who create senseless violence for public consumption.

THE LITTLE DOG LAUGHED by Douglas Carter Beane A scathing and hilarious look at Hollywood mores and double-standards, Beane’s sharp comedy about a fast-talking, amoral agent who’s trying, by any means necessary, to keep her young star client from coming out of the closet manages to have its cake and eat it too, because the crass, soulless agent is also the most perceptive and funniest person on the stage.

LOOPED by Matthew Lombardo Although Tallulah Bankhead was better known for her stage work and for her flamboyant and risque public persona, this recent Broadway outing chose to focus on the star as she struggles to re-record a single line of dialogue for an undistinguished film thriller, earning it a place on this list. Bankhead has proven a favorite of stage writers and stars, generating numerous shows about her life, includingTallulah, book by William F. Brown, lyrics by Mae Richard, Music by Ted Simon; Tallulah by Sandra Ryan Howard; Tallulah Who? with book by William Rushton, music and lyrics by Suzi Quatro and Shirlie Roden; Tallulah, A Memory by Eugenie Rawls; and Tallulah Hallelujah! By Larry Amoros, Tovah Feldshuh and Linda Selman.

MACK AND MABEL book by Michael Stewart , music and lyrics by Jerry Herman The intertwined professional and personal lives of early filmmaker Mack Sennett and his leading lady Mabel Normand are the basis for this much-tinkered-with musical about their romance. A favorite of musical theatre buffs, it has a hard time reconciling the darker aspects of the true-life tale to the musical comedy conventions that were still in place when it was created, resulting in numerous attempts to “fix” the show in the more than 35 years since its short-lived Broadway premiere.

A MAP OF THE WORLD by David Hare An extremely complex play which takes place in Bombay at a 1978 UNESCO conference on poverty, as well as at a contemporary British film studio where a movie is being made about the conference’s behind-the-scenes events, based upon a novel about the conference. Needless to say, the film of the novel of the conference is highly reductive, highlighting the failure of moviemaking to do justice to either the novel or its factual basis.

MARILYN: AN AMERICAN FABLE book by Patricia Michaels; music and lyrics by many collaborators Though inevitably any retelling of the short, tragic life of Marilyn Monroe would at face value be bound to be an indictment of Hollywood, this musical treatment focused more on her men than her movies. But hers was a Hollywood life after all, so this merits inclusion, despite the Broadway production being, you should pardon the expression, a candle in the wind.

MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG book by George Furth, music and lyrics by Stephen SondheimWhile the anti-hero of George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s original play was a theatrical success, Furth and Sondheim begin their backward-moving musical with their compromised writer having sold out to Hollywood after having begun in the theatre. Sharp barbs are tossed at movie society in the earlier parts of the show, before we move backwards to a time of more integrity and before that, aspiration.

MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG book by George Furth, music and lyrics by Stephen SondheimWhile the anti-hero of George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s original play was a theatrical success, Furth and Sondheim begin their backward-moving musical with their compromised writer having sold out to Hollywood after having begun in the theatre. Sharp barbs are tossed at movie society in the earlier parts of the show, before we move backwards to a time of more integrity and before that, aspiration.

MERTON OF THE MOVIES by George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly A bad actor becomes a comedy star when producer realize his incompetence in drama results in successful comedy. Quite remarkably, the play debuted in 1922, based on a 1919 book, making it one of the earliest stage satires of Hollywood and finding success while the silent film era was still in full swing.

MINNIE’S BOYS book by Arthur Marx and Robert Fisher, music by Larry Grossman, lyrics by Hal Hackady This is included only to point out why it doesn’t belong here. The story of the Marx Brothers and their mom (a regular Mama Rose was she), focuses entirely on their vaudeville days and ends with their discovering their trademark personas, which were honed on stage before being transferred to Hollywood.

MIZLANSKY/ZILINSKY, OR SCHMUCKS by Jon Robin Baitz Schlock producer Davis Mizlansky has the I.R.S. breathing down his neck as he works to convince his partner Sam Zilinsky to embrace the idea of celebrity retellings of Bible stories for children, such as “Sodom and Gomorrah: The True Story,” even though the backer for the project may also be a Nazi sympathizer.

MOONLIGHT AND MAGNOLIAS by Ron Hutchinson Focused on the five days in which producer David O. Selznick, writer Ben Hecht and Victor Fleming rewrote the screenplay of Gone With the Wind, this true-life tale chooses to play artistic desperation and potential financial ruin for laughs. Of course, we know the resulting film was a big hit, so there’s little need for reverence or any genuine suspense.

MY FAVORITE YEAR book by Joseph Dougherty, music by Stephen Flaherty, lyrics by Lynn Ahrens Although it’s one of the many fictionalized dramatizations of life behind the scenes at Sid Caesar’s television hit Your Show of Shows, MFY belongs on this list because of its portrayal of Alan Swann, a dissipated one-time swashbuckling star, now reduced to a guest shot on the new medium known as television, and the idealized Hollywood dreams of our protagonist, young Benjy Stone, that, as a result of Swann’s personal failings, are forced to fall by the wayside. Life is not like the movies at all.

NINE book by Arthur Kopit, music and lyrics by Maury Yeston Fellini’s film 8 1/2 is the basis for this highly stylized musical about film director Guido Contini and the many women in his life. While the backdrop is moviemaking (although in this case Cinecitta rather than Warner Brothers), it’s the relationships that form the backbone of the episodic story.

ONCE IN A LIFETIME by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman A light-hearted satire of three out of work actors who head west to find work in the new field of talking pictures, convinced that their stage training will give them an edge over the once-silent stars of the era, this was first written by Hart and subsequently polished in partnership with Kaufman in the first of their eight collaborations. The show was promised several years ago as a musical, GOING HOLLYWOOD, by David Zippel, Jonathan Sheffer and Joe Leonardo, but it has yet to materialize.

PASSIONELLA from The Apple Tree, book by Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick, music by Bock and lyrics by Harnick The final chapter of Bock and Harnick’s tripartite chamber musical is drawn from Jules Feiffer‘s illustrated subversion of the Cinderella tale, in which a chimney sweeping drudge is transformed into a glamorous movie star. For the trivia minded, this was the second effort to bring Passionella to the musical stage; the earlier failed version was by Feiffer and some guy named Sondheim.

POPCORN by Ben Elton Stop me if you’ve heard this one: two killers on a serial murder spree hole up at the home of the schlock action film producer whose movies have inspired them and, knowing they’re likely to be caught soon, force the producer to accept the responsibility for their own depraved behavior. Adapted from Elton’s own 1996 novel of the same name.

ROAD TO NIRVANA (aka BONE-THE-FISH) by Arthur Kopit A conflation of David Mamet’s Speed-the-Plow and its original much-hyped Broadway production starring Madonna, this structurally and dramatically similar play expresses its own contempt for the state of modern Hollywood but seems to have contempt for Mr. Mamet’s tale as well, in this case telling the story of a rock star who attempts to pass off Moby Dick as her autobiography, with her in the place of Ahab, and the competitive producers vying to one-up each other.

THE ROYAL FAMILY by Edna Ferber and George S. Kaufman Yes, yes, I know it’s primarily focused on its two leading ladies, stage doyennes Fanny and Julie Cavendish, and modeled on The Barrymores, but there are more than a few poisoned arrows pointed at Hollywood via the character of Tony Cavendish, who has forsaken the stage for the louche and lucrative world of the screen.

SEARCH AND DESTROY by Howard Korder A morally bankrupt young man on the lam from the I.R.S. takes refuge where only such an empty vessel can succeed: Hollywood, where he embarks on a series of misadventures including drug abuse and murder in preparation for producing his first movie, Dead World.

SHAKESPEARE IN HOLLYWOOD by Ken Ludwig Based in the true-life making of the classic film version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream by recent refugee Max Reinhardt, the farceur Ludwig ups the ante by having the “real” Oberon and Puck materialize on the film set to complicate the production.

SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN book adapted by Betty Comden and Adolph Green from their screenplay, with pre-existing songs Amidst so many dark visions, Singin’ in the Rain is a ray of sunshine of stage shows about the movies, admittedly a straightforward adaptation of the utterly delightful love letter to Hollywood that is the original film, turning on the transition from silent films to talkies. One of the early cases of an original film musical subsequently being turned into a stage vehicle, the stage Singin’ marked the Broadway debut of Twyla Tharp as director and choreographer.

SLASHER by Allison Moore If the making of porn can be the subject of a stage play about movies, then the slasher genre should get a shot (or cleaver, or buzzsaw) too. Moore’s play portrays Sheena, a Texas waitress who secures a role in a low-budget horror film shooting nearby in order to make ends meet, the prospect of which causes her wheelchair-bound mother to go…CRAZY! A simultaneous spoof of horror films and feminist commentary on their objectification of women.

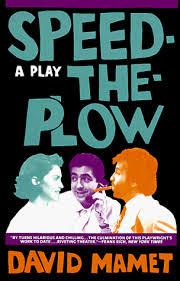

SPEED-THE-PLOW by David Mamet A crass, driven Hollywood big shot comes to question his profession and his purpose when he has to choose between making a sure-hit blockbuster and an esoteric film championed by his temp assistant. Like so many plays of Mamet, an accomplished screenwriter and film director, the story particulars are less important than the gender politics and macho battles that erupt within it.

SPEED-THE-PLOW by David Mamet A crass, driven Hollywood big shot comes to question his profession and his purpose when he has to choose between making a sure-hit blockbuster and an esoteric film championed by his temp assistant. Like so many plays of Mamet, an accomplished screenwriter and film director, the story particulars are less important than the gender politics and macho battles that erupt within it.

STONES IN HIS POCKETS by Marie Jones Not unlike The Cripple of Inishmaan, Stones portrays the effects of a film crew’s arrival on a small Irish village, once the location for filming of The Quiet Man, although in this case the film is big budget Hollywood epic and the entire village is portrayed by only two men. While it has its share of standard Hollywood satirical jokes, Stones manages to retain a vision of Hollywood as a dream factory and America as a land paved with gold, even as it shares some darker stories of the filming, including the one that gives the play its name.

SUNSET BOULEVARD book by Don Black and Christopher Hampton, music by Andrew Lloyd Webber, lyrics by Black and Hampton The classic film noir by Billy Wilder, of a forgotten silent screen siren who dreams of a comeback and her ill-fated dalliance with a down on his luck screenwriter, is transferred to the stage with a good bit of its tawdriness intact. The deluded, pathetic, grasping Norma Desmond and her kept man Joe Gillis encapsulate everything that’s was wrong with Hollywood for two different generations.

THEDA BARA AND THE FRONTIER RABBI book by Jeff Hochhauser, music by Bob Johnston, lyrics by Hochhauser and Johnston A young rabbi’s forbidden attraction to the films of silver screen siren Theda Bara, Bara’s true identity as Theodosia Goodman (who just wants to find a nice Jewish boy to settle down with), and the efforts of one Selwyn Farp to have the rabbi lead a movie industry watchdog group form the basis of this musical romantic comedy that manages to mix religious issues into the standard tale of Hollywood allure and true life values.

THE VAMP book by John LaTouche and Sam Locke, music by James Mundy, lyrics by LaTouche Created as a vehicle for Carol Channing, this musical take-off on the silent screen career of – here she is again – Theda Bara proved one of Channing’s rare flops (60 performances), of which she later wrote that she should have simply walked out while it was out-of-town in Washington.

TRUE WEST by Sam Shepard Though it’s the sibling rivalry that most recall about this Shepard comedy, one shouldn’t forget that at the start, brother Austin is at work on a screenplay, one of the four characters is an unctuous film producer, and the filmic metaphor of what the west really represents gets trashed as the brothers metamorphose as a result of their dangerous proximity.

TWENTIETH CENTURY by Ben Hecht & Charles MacArthur/ON THE TWENTIETH CENTURY book by Betty Comden and Adolph Green, music by Cy Coleman, lyrics by Comden & Green Although the main focus is on theatre in both the play and musical version of a down on his luck theatrical producer who works to woo his one-time protégée back to the stage and into his arms, there are zingers aplenty for Hollywood as producer Oscar Jaffe works to win a contract out of screen siren Lily Garland (nee Mildred Plotka).

WHAT A GLORIOUS FEELING by Jay Berkow with pre-existing songs Belonging to the “let’s look behind the scenes of a movie we all know well,” this play with songs focuses on the romantic triangle between Singin’ in the Rain‘s co-directors Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen and the film’s dance captain and Donen’s ex-wife Jeanne Coyne. Portrayals of producer Arthur Freed and leading lady Debbie Reynolds round out the cast. And for those who shout “jukebox musical,” just remember that the originalSingin’ didn’t have original songs either; they were drawn from a back catalogue of 20 to 30 years vintage.

* * *

While I began with a disclaimer regarding the completeness of the list you’ve just read, I would be remiss if I didn’t note that a new addition will be making its debut very shortly: BY THE WAY, MEET VERA STARK by Lynn Nottage. Because the play has not yet had its world premiere — it begins previews in April at New York’s Second Stage) — I will borrow a synopsis from that theatre’s marketing copy: “the life of Vera Stark, a headstrong African-American maid and budding actress, and her tangled relationship with her boss, a white Hollywood star desperately grasping to hold on to her career. When circumstances collide and both women land roles in the same Southern epic, the story behind the cameras leaves Vera with a surprising and controversial legacy.” And thus another play about the movies is born.

* * *

I would like to thank the many folks who helped me to build this list, even those whose suggestions may not have made the cut as a result of my arbitrary and mercurial nature and guidelines. Via Twitter, I give my appreciation to:

@awkwarddanny, @bengougeon, @charlenevsmith, @danaboll, @devonvsmith,

@dloehr, @dramagirl, @forumtheatre, @fronkensteen, @galoka,

@_hesaid_shesaid, @humphriesmark, @kevinddaly, @kingduncan, @labfly,

@organsofstate, @pawofthepanther, @patrica666, @pksfrk, @pollycarl,

@raisinsliaisons, @reduced, @spaltor and @thenygalavant.

Via Facebook and e-mail, I am indebted to Casey Childs, Roger Danforth, Michael Dove, Jane Lipka Helfgott, Larry Hirschhorn, Dawson Howard, Ben Pesner, Heather Randall, Scott Rice, Ellen Richard, Eric Savitz, Susan L. Schulman, Ed Windels, and Randall Wreghitt. MVP goes to Bert Fink.

This post originally appeared on the American Theatre Wing website.

This is Not a Political Blog

February 14th, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

|

While a significant portion of the theatre community was distracted over the past several weeks by the fallout from Rocco Landesman’s statements about there perhaps being too many theatres, a more imminent problem began a journey through the halls of government. I’m speaking of proposed cuts to the National Endowment for the Arts, which overnight between Thursday and Friday nearly doubled, even before most people were aware that any cuts were on the table. Now if you’ve been working in not-for-profit theatre as long as I have, cuts –- and proposed cuts — to the NEA are hardly new. Frankly, it seems an almost annual event, not unlike the buzzards returning to Hinckley Marsh, and at a certain point for many, it has perhaps become just so much white noise. Given the state of technology, we can now vent our spleen by filling in some blanks on the website of Americans for the Arts or their Arts Action Fund (http://ArtsActionFund.org/) or we can try to rally the troops via Twitter, Facebook and blogs, but every time this rises to the surface, the horse is already out of the barn, and those who would minimize or eliminate the NEA have the upper hand and momentum. Indeed, I sense exhaustion among those who choose to voice their thoughts on this issue, since what was once a rallying cry to save the NEA seems to be giving way to questions about whether the NEA is worth saving at all. I suppose having its chairman question the necessity of your existence can do that. But because this is, as the title states, not a political blog, I won’t attempt to dissect the history and reasons behind the ongoing use of the NEA as a symbolic whipping boy for proper values or economic responsibility. I will, however, take a moment to cast blame. But that blame is turned inward. The reason the NEA (and the NEH and NPR and PBS) make for such easy targets is that their audiences and their artists fail to make a case for their intrinsic value. Yes, we’re asked that if we like “Masterpiece” (recently shorn of “Theatre”) on PBS, won’t we make a donation and receive a tote bag, but we never really hear why such programming is important and why it must be sustained. Frankly, I rarely watch PBS and wonder why its pledge specials often feature doo-wop groups from the 50s or aging troubadors from the 60s, so perhaps even I need to be shown why there’s value in government supported not-for-profit TV, and since I don’t watch, I need to get that case delivered through some other vehicle. A big part of the problem is that those of us who are profoundly dedicated to the arts hold them as a sacred belief; we are called to them as surely as religious leaders are called to the cloth. Yet to pursue the comparison, religious leaders spend one day every week making the case for the relevancy and value of their religion (these are called sermons), while we spend our time selling tickets to individual productions or exhibits. The reason the arts and humanities are targeted is that for a major portion of the country, we are either a complete blank or the spawn of the upper-class elites. We fail to make the argument for the value of our field, because we’re too busy getting butts in seats or bodies through turnstiles. We rally to a certain degree in times of crisis, but the moment the crisis passes, we return to our individual pursuits, proud of whatever we may have achieved to protect support for the arts, or even just for having tried. This simply isn’t enough; if all we do is react, we’re always playing defense. Every so often, there’s a minor ripple of interest in creating a “Got Milk?” campaign for the arts, designed to bring awareness and instill messages about the value of the arts in our lives. It hasn’t ever gotten off the ground in a big way, and I can’t say whether it’s because of a lack of creative spark, a lack of cohesion among the disparate arts field, or perhaps because lack of funds. I happen to think that, specifics of a campaign aside, this is our greatest failing and the reason the arts remain a perpetual punching bag. We just don’t know how to tell people why we’re worthwhile. After all, our friends and peers are committed to the arts, and so are our audiences. ‘See,’ we think, ‘there’s evidence of the value.’ If cotton and cheese need to remind us of there worth, surely culture does as well. But we have to figure out how to make that case for those who don’t work with us and who don’t often – or ever – participate with us. We have to take those genuine statistics about economic impact, those many studies about how we help young people to think and learn, and turn them into an ongoing platform that is reiterated year in and year out, not just in times of hardship, conflict or elections. I have written and spoken on many occasions on how essential it is that we stop “talking to ourselves,” getting outside our rarified circles and our assorted conferences in order to speak to the majority of the public, not just those who have self-selected themselves or who we have inveigled into our theatres, our concert halls and our museums. We cannot speak with the gentility and subtlety that often characterizes the best work of our fields and instead create bold, motivational messaging that befits an important industry (and yes, I know how much that word “industry” is reviled by those inside of it, but since money is the core of our need to survive, adopting the language of the marketplace doesn’t sully our reputations). Is the country oversupplied with arts at this moment? Is the NEA the best vehicle for distributing public monies to the arts? At a time when federal, state and local governments cannot balance their budgets, should the arts remain as expense items? Those are political questions and, per my title, this is not a political blog. All I know is that if the arts are to operate on any model other than a commercial one, we have to raise funds, from all sources – individual, corporate, foundation and government – at a time when essential services (which I believe the arts to be, lest you be confused by this diatribe) are all under fire. So let’s gather our painters, our sculptors, our actors, our dancers, our singers, our filmmakers and get behind a singular, cohesive message and get it out in the field of public opinion. And let’s be prepared to never stop the campaign, lest other campaigns stop us. It’s a good fight, but it’s also one we’ll never win. The best we will ever do is live to fight the good fight another day.

This post originally appeared on the American Theatre Wing website. |

It’s Not A Contest

February 7th, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

|