March 4th, 2015 § § permalink

Remember Trumbull, Connecticut?

That’s the town where a new high school principal canceled a production of the student edition of the musical Rent in the fall of 2013. The resultant outcry from students, parents, town residents, the media and interested third parties (including me) was such that three weeks later, the show was reinstated. It was produced at the high school in 2014 without any incident.

After my advocacy for Rent, I hate returning to the subject of the arts in Trumbull, for fear of being accused of piling on. That said, there must be something in the water supply in Trumbull, because it’s right back at the center of an arts censorship controversy again. Timothy M. Herbst, the town’s first selectman, has ordered the Trumbull Library to remove a painting by Robin Morris from a current exhibition, “The Great Minds Collection,” commissioned and loaned by Trumbull residents Richard and Jane Resnick. The painting in question, “Women of Purpose,” features representations of a number of famous women, including Mother Teresa, Betty Freidan, Gloria Steinem, Clara Barton and Margaret Sanger.

After my advocacy for Rent, I hate returning to the subject of the arts in Trumbull, for fear of being accused of piling on. That said, there must be something in the water supply in Trumbull, because it’s right back at the center of an arts censorship controversy again. Timothy M. Herbst, the town’s first selectman, has ordered the Trumbull Library to remove a painting by Robin Morris from a current exhibition, “The Great Minds Collection,” commissioned and loaned by Trumbull residents Richard and Jane Resnick. The painting in question, “Women of Purpose,” features representations of a number of famous women, including Mother Teresa, Betty Freidan, Gloria Steinem, Clara Barton and Margaret Sanger.

The Bridgeport Archdiocese of the Catholic Church has already made its dismay over the painting known, due to the juxtaposition of Mother Teresa with Sanger, who founded Planned Parenthood. Library Director Susan Horton says she has received eight messages complaining about the painting, all from men. It is not yet known what complaints may have gone directly to Town Hall, prompting Herbst to pull the painting (the Resnicks’ attorney has filed a Freedom of Information Request to determine whether his client’s property is being unfairly singled out).

In fact, Herbst won’t admit to complaints being the cause for the painting’s removal at all. He refers instead to threats of copyright infringement for depicting Mother Teresa and the lack of an indemnification from the Resnicks against any claims arising from the display of the paintings.

“After learning that the Trumbull Library Board did not have the proper written indemnification for the display of privately-owned artwork in the town’s library, and also being alerted to allegations of copyright infringement and unlawful use of Mother Teresa’s image, upon the advice of legal counsel, I can see no other respectful and responsible alternative than to temporarily suspend the display until the proper agreements and legal assurances are in place,” Herbst said. “I want to make it clear that this action is in no way a judgment on the content of the art but is being undertaken solely to protect the town from legal liability based upon a preliminary opinion from the town attorney.”

I heard Mr. Herbst in action during the Rent incident, when he went on radio several times trying to assume the role of peacemaker. Instead, he merely offered unworkable solutions that were clear to anyone familiar with the school and the town’s youth theatre troupe. It should be noted that as first selectman, he doesn’t control the school system. That is the purview of the elected school board, which is chaired by his mother, who was all but silent throughout. As before, I find his current protestations to be a smokescreen.

First, this isn’t a copyright issue, since the painting is an original work of art and no one appears to have claimed that it is in some way derivative of another copyrighted work. There is the possibility that Mother Teresa’s image may have some trademark protection, as claimed by the Society of Missionaries of Charity in India on their website, but the assertion of trademark is not proof of ownership and the organization offers no documentation of their claim; it’s worth noting that there are numerous organizations operating in Mother Teresa’s name, which suggests that policing of the trademark is shoddy at best. Additionally, the fact is that a privately commissioned painting in private hands is unlikely to constitute an infringement of rights that causes confusion in the marketplace, something trademark is meant to protect.

Second, Richard Resnick has said he would be pleased to offer indemnification to the town for the display of the painting, which would make any issue disappear. Herbst asserts he needs time for an attorney to draft something, but any attorney with even limited experience could produce straightforward “hold harmless” language in perhaps an hour’s time. Frankly, I have more than a few on my hard drive from literary agreements, since it’s not uncommon for playwrights to hold producing organizations harmless from any claims against a work that as challenged as not being wholly original to the author. The fact that Herbst has already tried to throw the town librarian under the proverbial bus for not getting such documentation is shameful, since if such protection is regularly required, why hasn’t the town’s attorney prepared a document for each and every exhibit the library has ever shown, that can just immediately be pulled out of a file? If Horton failed to get one signed, then it should be readily available for Resnick’s promised immediate signature; if it hasn’t been required previously, then the fault lies with Herbst and the town’s attorney.

When Principal Mark Guarino tried to defend his cancellation of Rent, he took refuge behind vague terms like ‘challenging issue.’ Now we have Herbst hiding under the guise of proper legal procedure, which is a flimsy excuse for what seems quite obviously an attempt to censor work which some find displeasing. In doing so, Herbst has placed himself in the unenviable situation of being damned either way: if the painting stays down, he’s a art censor (which he adamantly claims he is not) and if it’s restored he’s alienating members of his constituency who may object to the painting on religious, ideological, political or even artistic grounds. This is a fine mess he’s gotten himself into, and for someone who apparently harbors greater political ambitions – he lost the race for state treasurer by a narrow margin in 2014 – he’s placed his ideology squarely in front of voters for any future campaign, while ineptly handling a situation that is quickly rising to the level of crisis.

Regarding theological opposition to the painting, it’s worth noting that it was on display at nearby Fairfield University in 2014 without any incident. Oh, and for those unfamiliar with the colleges and universities of southern Connecticut (where I grew up), it’s important to note that Fairfield is a Catholic school. Why didn’t the Archdiocese or the Society of Missionaries in Charity raise their issues during that three-month exhibition?

Tim Herbst could make the charges of censorship go away instantly with one single document. But as he keeps throwing up roadblocks, it’s obvious that he’s not protecting the town from legal claims, but rather serving other interests. If Herbst is trying to establish his conservative cred, he may well get himself exalted in certain partisan quarters only to be vilified in others. The question is whether his actions are bolstering the profile and needs of Trumbull, Connecticut, or those of Timothy M. Herbst, the once and future candidate?

While it’s a tenuous linkage, I’d just like to toss into the pot that Herbst’s town budget has zeroed out the annual allocation for the town’s popular summer theater operation, the Trumbull Youth Association. This is the same TYA program that Herbst suggested could provide a home for Rent if it couldn’t be done at the high school (although that wasn’t a workable alternative for several reasons). If we’re looking for patterns about art and Trumbull, one does seem to be emerging.

And just to cap this off, it has been noticed that in discussing the withdrawal of the painting from the library exhibit, the Trumbull town website reproduced the painting itself. If Herbst is so concerned about copyright infringement, didn’t he just place the town at risk once again? Seems like a contradiction to me.

Update March 4, 2 pm: I just spoke briefly with Jane Resnick, as we both called in to “The Colin McEnroe Show” on WNPR in Connecticut. Mrs. Resnick affirmed that she and her husband had always been prepared to indemnify the town against any damage that might occur while their paintings were on display in a town facility and that, while they had not anticipated the need, they would also hold the town harmless from any copyright claims that might possibly be forthcoming.

Update, March 4, 4 pm: Regarding First Selectman Tim Herbst’s efforts to zero out the budget of the Trumbull Youth Association, it has been reported today by the Trumbull Times that just last night, the town’s Board of Finance overruled the cut, and the funding was restored, against Herbst’s wishes.

Update, March 4, 5:15 pm: The Hartford Courant, the state’s largest newspaper, declares in an editorial, “Public works of art, like library books, should not be held hostage to the complaints of a few whose sensibilities are offended.”

Update, March 4, 5:30 pm: The Trumbull Times reports, via e-mails it has seen, that organized opposition to the display of the painting originated with the Catholic fraternal organization the Knights of Columbus, and indicates that a town councilman assured members of the group that the painting would be coming down as early as February 14, and suggested that First Selectman Herbst was in support of its removal. Herbst, however, denies that this was the case, and says that an indemnification agreement has been provided to Dr. Resnick and that, “As soon as the agreement is executed by Dr. Resnick, the artwork can be re-hung in the library.”

However, Herbst goes on to say that “Public buildings should bring people together to have an open exchange of alternate points of view,” which seems positive, save for the fact that it is immediately followed by, “Public buildings should not make any member of the community feel that their point of view is secondary to another,” which seems exceedingly vague and undercuts the prior statement. A single work of art rarely pleases everyone. If dissatisfaction or dislike of a work of art, or a book, can be construed as making someone feel “secondary,” what is to prevent future efforts to remove controversial content from the Trumbull Library?

Update, March 6, 12 pm: The Trumbull Times reports that Dr. Resnick has returned a signed indemnification agreement to the Town of Trumbull. There is no word yet on whether the painting has been restored to its place in the library.

Update, March 6, 3:30 pm: While the disputed painting has been rehung just now, the Town of Trumbull is now demanding a “comprehensive indemnification” for all of the paintings from their owner Dr. Richard Resnick, without which the entire collection will be taken down as of 5 pm. The letter from first selectman Herbst to Dr. Resnick’s attorney has been made public by the Connecticut Post.

Update: March 9, 12 noon: So far as I know at the moment, the entire collection is currently hung at the Trumbull Library. A series of claims and counterclaims between First Selectman Herbst and attorney Bruce Epstein on behalf of Dr. Richard Resnick have been made in correspondence, and shared with all interested parties via the Trumbull Times. They are: “Painting back up for now; but all could come down soon” (March 6, with updates); “Herbst and Horton: Chief wasn’t at meeting” (March 7, with updates), and “Resnick: I won’t be intimidated by Herbst’s demands” (March 8).

Update, March 11, 11:00 pm: At approximately 8 pm this evening, as the painting was being discussed at a meeting of the library board, an individual defaced the painting, reportedly by obscuring Margaret Sanger’s face. The Trumbull Times reported on the developments.

As of March 12, there will be no further updates to this post, but please refer to my newer post, “The Shameful, Inevitable Result of The Trumbull Art Controversy” for any additional details.

Howard Sherman is the director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama in New York.

Note: crude or ad hominem attacks in comments will be removed at my discretion. This is not censorship, but my right as the author of this blog to insure that conversation remains civil. Comments will not be removed simply because we disagree.

February 25th, 2015 § § permalink

It is not, sad to say, news that controversy has surrounded a production of Terrence McNally’s Corpus Christi. It is certainly not surprising to hear that such controversy took place on a university campus. But when one hears that Corpus Christi became the subject of controversy as a result of a production at a Christian faith-based university, the reflex is to wonder how anyone ever thought it could be done there in the first place. But the production of Corpus Christi that was to have been produced this past weekend at Eastern Mennonite University in Virginia reveals a situation that demands something more than a reflexive scoff, as it reveals a great deal about the struggle between the tenets of faith and academic freedom, between traditional ways and where our society is in the 21st century.

It is not, sad to say, news that controversy has surrounded a production of Terrence McNally’s Corpus Christi. It is certainly not surprising to hear that such controversy took place on a university campus. But when one hears that Corpus Christi became the subject of controversy as a result of a production at a Christian faith-based university, the reflex is to wonder how anyone ever thought it could be done there in the first place. But the production of Corpus Christi that was to have been produced this past weekend at Eastern Mennonite University in Virginia reveals a situation that demands something more than a reflexive scoff, as it reveals a great deal about the struggle between the tenets of faith and academic freedom, between traditional ways and where our society is in the 21st century.

The basic facts are this: Christian Parks, a senior majoring in theatre at Eastern Mennonite University (EMU) proposed as his senior project a production of Corpus Christi, which was, according to him, approved by the school’s theatre faculty in the spring of 2014. Since January, due to increasing concerns by the school administration over the content of the play, Parks was called into a series of meetings about the play, which escalated from expressing concern to reducing the number of performances from four to two and severely limiting who would be permitted to attend to the show being completely canceled. It seems to echo many cases of academic theatre censorship, although there appears to have been significantly more dialogue surrounding the process as it accelerated – and how the final decision was made, and by whom, seems unique in my experience.

* * *

For those unfamiliar with Corpus Christi, it is McNally’s 1998 play in which he reimagines the story of Jesus as told and enacted by 13 gay male friends in the present day. When it was first announced for its premiere at the Manhattan Theatre Club, it was thrust into the center of controversy over its content – which few people had seen or even read – resulting in violent threats against MTC and the production, causing it to be briefly canceled and then restored, with strong protests outside the theatre during its run and security measure put in place to protect the theatre, the show and its patrons.

The play subsequently had numerous productions around the country, many which had their own controversies where it played, again, often over what people imagined to be the content rather than the play itself. It has been produced at colleges and universities, provoking similar reactions. Now, 17 years later, the play is produced intermittently, hardly surprising for any play that, in its way, had such a huge “moment” in the late 90s.

Writing of the play in the preface to the trade paperback edition, McNally describes it as follows:

Corpus Christi is a passion play. The life of Joshua, a young man from south Texas, is told in the theatrical tradition of medieval morality plays. Men play all the roles. There is no suspense. There is no scenery. The purpose of the play is that we begin again the familiar dialogue with ourselves: Do I love my neighbor? Am I contributing to the good of the society in which I operate or nil? Do I, in fact, matter? Nothing more, nothing less. The play is more religious ritual than a play. A play teaches us new insight into the human condition. A ritual is an action we perform over and over because we have to. Otherwise we are in danger of forgetting the meaning of the ritual, in this case that we must love one another or die. Christ died for all of our sins because He loved each and every one of us. When we do not remember His great sacrifice, we condemn ourselves to repeating its terrible consequences.

All Corpus Christi asks of you is to “look at what they did to Him. Look at what they did to Him.” At the same time it asks you to look at what they did to Joshua, it asks that we look at what they did one cold October night to a young man in Wyoming as well. Jesus Christ died again when Matthew Shepard did.

* * *

The play is set in the present day and employs language that might raise concerns within religious groups, but McNally’s message of dialogue and ritual seems particularly well suited to the discussion of faith in present day life. That said, it helps to know something about the Mennonites. Here I’ll draw from the website of Mennonite Church USA.

Mennonites are Anabaptists

We are neither Catholic nor Protestant, but we share ties to those streams of Christianity. We cooperate as a sign of our unity in Christ and in ways that extend the reign of God’s Kingdom on earth.

We are known as “Anabaptists” (not anti-Baptist) – meaning “rebaptizers.” The Anabaptist movement began in the 16th Century in Europe.

To defuse a commonly held misconception I also draw from their website the following

Mennonites are not Amish

We find that many people asking about Mennonites are actually thinking of the Amish or “Old Order Mennonites.” Mennonites and Amish come from the same Anabaptist tradition begun in the 16th century, but there are differences in how we live out our Christian values. The distinctiveness of the Amish is in their separation from the society around them. They generally shun modern technology, keep out of political and secular involvements and dress plainly.

It is important to know, however, that there is great debate within the Mennonite community about the acceptance and role of LGBTQ followers, which has historically been one of exclusion. However, as in so many faiths, there is a strong contingent of Mennonites who want to see the church change its ways, and there are groups working to bring that about. But there is no agreement.

* * *

Christian Parks first proposed doing Corpus Christi as his senior project two years ago, inspired by seeing a production of the play in San Francisco by 108 Productions as part of their “I Am Love” effort to bring the play and its message to communities around the country, including communities of faith.

“There is an application process,” Parks explained, describing the theatre department’s standard procedures, “where I give them the name of the script. I also give them the reasons why I’m doing the project. I also give them a budget that I had to pre-balance, so that they knew where I was going to spend my money. Then we began more discussions after the script had a read-through and that’s when the conversations about this being a student lab production entered in. That entails making sure there’s a talkback, a way for the audience to process the show after every performance and it also means the department will not collectively advertise this outside the campus.”

Parks explained that a lab production is a full production, with four performances, and that while it may not be advertised off campus, the local community may attend. He then said, “I got approval when the season was approved, in the spring of 2014. Surprisingly enough, the administration is mailed every season that gets approved and this show was on the list.”

Asked as to whether he was aware of the play’s controversial past, he said, “In the fall, I began my senior thesis, which is the theoretical part which goes along with the production. I wrote a conceptual, theorized piece using poor theatre and Grotowski and using some other things that had more to do with the ritual side of Corpus Christi. I actually had to dive into the script and look at past performances, where this had been and the controversy that has been around it. So yes, I was very aware of everything that was around Corpus Christi. But it was a lab production, so that was the clearance, or should I say the filter, in which I said that ‘Yes, this is a thing but we’re doing it as a lab production. That will be alright.”

Had Parks considered that the play might not be approved?

“It was a little iffy because I’m in a religious community and an especially close-knit one like the Mennonites. The university, according to the process we went through last year, was ahead of the church, so I knew that on the church denominational level will do whatever it does, and yes it’s going to make some conflict, but that’s OK because there’s enough people who can take care of that.”

“The process” Parks refers to was a “Listening Process” on the EMU campus in 2014, which sought to address issues relating to LGBTQ representation, particularly among the faculty. After six months, the school deferred formal action on hiring policy. Parks’s proposal was being considered by the theatre faculty during this time.

“I wasn’t aware,” he said, “that there was enough harm and enough pain and enough tension in the process that we went through, because in the spring of 2014 we approved it as a department in the middle of the listening process. It seemed, especially with the concept around the show, as if it would fit the culture that we were in and becoming.” Asked about his reference to “pain and hurt,” Parks explained that he was referring to situations that arose, “any time you have a lot of straight people talking about queer and gay bodies, and just constantly being under the microscope as they figure out what to do with us. So this show was a way of finally putting our voice at the table that they tried to do with us last year, but it didn’t really work because they still don’t understand and don’t want to understand.”

* * *

Parks said that conflict over the play began when he put out his audition notice at the beginning of January, which included a description of the play. Parks then described a series of meetings that he was called to by the administration beginning in late January. The first two were led by the Provost and Academic Dean; at the first, Parks said he was made aware of “concerns” and was asked to provide the script. He said that the provost subsequently stated that he never completed reading it, having stopped at the play’s nativity scene, at roughly page 20. Parks was also asked for his director’s notes and his advisor was asked for an explanation of the standard lab process.

At the second meeting, a week later, he said “We prepared a resource list and they took four or five of their resources and I took four or five of my resources and we were going to synthesize them together for people who might have more questions and might need places to go.” Parks also said that at that time, there was some concern as to whether he could field a full cast, and that the possibility of a reading instead of a full production, which would require less rehearsal, came up, but that he quickly thereafter secured a full cast and notified the theatre department that a production would be possible as originally planned. At a third meeting, this one called by the president, following a weekend meeting by the president’s cabinet, he was given a choice.

“The two decisions that they laid on the table for me was that either they would shut it down completely or, on the basis of academic integrity, they would confine the show to the classroom so that it would become a classroom endeavor which meant one performance at one time with a select group of people, a select group of classes and classes that were already dealing with subjects around sexuality conflict and faith. We compromised and went with one day instead of one performance and so there was a three o’clock and an eight o’clock performance. That is what we settled on and that each of these classes would get a ticket and only people who would be allowed to enter the theatre would be the people with a ticket, which meant that we would have to turn away anyone who came from the community and anyone who was a student but didn’t have a ticket.”

Following this decision, the restrictions on attendance were announced.

“It went on Facebook,” said Parks, “The theatre department had to tell people and that got out quicker than wildfire and what that means is that all of the justice connections that I have got whiff of it. People were angry and they went to social media to get out their anger. That is when I got called in for another meeting, Wednesday the 18th.”

This is now just prior to the two remaining scheduled performances, set for February 21.

* * *

I reached out to several people, via e-mail, in the EMU administration about the Corpus Christi situation. I did not receive a reply from Heidi Winters Vogel, Parks’s advisor and an associate professor, and my inquiries to the university president Loren Swartzendruber and provost Fred Kniss were referred to Andrea Wenger, Director of Marketing and Communications for the school. I should note that Wenger attempted to schedule direct conversation between me and the provost, however his schedule and my own were in conflict, and Wenger accepted and responded to my questions via e-mail at my suggestion in the interest of expediency.

I asked Wenger when the administration first became concerned about Corpus Christi and whether it was their practice to alter academic efforts in response to complaints over previously approved content.

She wrote, “Administrative leadership became aware of the play – and its controversial history – in mid-January. It is not the school’s practice to ‘alter academic efforts in response to complaints about previously approved academic content.’ Production of the play hadn’t been reviewed or approved by department leadership or administration prior to mid-January.”

Wenger explained that, “Public performances were cancelled by the president’s cabinet when administration learned that what they had been assured in mid-January would be a staged reading with no publicity morphed into a full-blown production.” Responding to my question about limiting attendance, she said, “The student involved intended to sell tickets to this show. He anticipated off-campus interest and support even with limited publicity. The administration cut the performance schedule from four performances over three days to two performances on one day with an invitation-only audience

She further said, regarding the timing of the process, “The administration first became aware of the planned staging in recent weeks. Administration is evaluating the process of how the play was selected and vetted. EMU students are given freedom to choose productions that explore controversial topics as part of a rigorous academic program.

A report on the cancelation of the play in the school newspaper quoted Swartzendruber as citing threats of violence over the play, although he acknowledged that those had been over other productions, and none had been made at EMU. Asked about this, Wenger responded, “Given the history of this play’s controversial nature – which in some settings has generated threats of violence – EMU leadership took the action that they believed was in the overall best interests of students’ safety and well-being. Leadership had enough information to be concerned about the possibility of disruption.”

* * *

Which brings us to the cancelation.

Which brings us to the cancelation.

The EMU student newspaper ran their story, on Thursday, February 19, with the headline, “Parks Cancels ‘Corpus Christi’ Over Controversy,” saying that the decision was his, not the administration’s. Regarding the accuracy of this account, Parks returned to the meeting of February 18.

“After hearing what was going on,” he said, “and after doing some strategic planning in my mind, that is when I went in and I knew that they were going to shut it down. I knew. And so instead of the story being written as they shut it down, I’d rather it be written as I took it down, because I refuse to be a victim. I refuse, I refuse. So that’s when I made the decision, Wednesday the 18th, that Corpus Christi is coming down and we would not be having the performance and so I went back and told my cast.

I wondered whether Parks had jumped the gun, and asked Andrea Wenger whether the administration would have permitted the performances to go on had Parks said he was canceling them

“No,” Wenger replied. “The invitation-only performances were to be cancelled; administration believed this to be in the overall best interests of EMU students’ safety and well-being. Administration had enough information to be concerned about the possibility of disruption — especially when it became apparent that the students were proceeding with a full production versus a staged reading as originally planned.”

That statement stands in relief against a university wide communication by Wenger on behalf of Swartzendruber on February 18 which read, in part, “Despite the nature of the play, which varies from the university’s theological and biblical understandings, the cabinet sought to protect academic freedom and honor the student project as an academically engaging activity intended primarily for an internal audience,” then citing Parks’s decision as coming in the wake of the “intense reaction to the planned staging.” It doesn’t point out that the intense reaction was coming, at least in part, from the administration itself.

So no matter what had took place, and who spoke first, Corpus Christi wasn’t going to be seen at Eastern Mennonite University. The administration has responsibility for the denouement.

* * *

Seeking more perspective on the situation, I reached out to Barbra Graber, the co-chair of the EMU theatre department when she retired in 2005, having first started on the faculty in 1981. She had made several public postings on social media, which led me to her.

I asked her about the process that had taken place, which, when we spoke (preceding my communications with Parks and Wenger), she only had learned about the situation through friends and former colleagues on campus and what she had seen on social media. She also made clear that while she was familiar with McNally’s work, she did not know Corpus Christi.

Graber said, “It was troubling to hear that EMU pulled this play at all after it being passed through the theatre department. For the president’s office to feel that they just have the right to pull something the theatre department has already approved and that students have put their heart and soul into, you need to let the show go on. You can’t just step in and make that decision. It is a blatant misuse of freedoms, of rights, all kinds of rights violations going on there.”

“Religious people love to make decisions for other people and think they have a right to do that and they think they have the corner on what should or shouldn’t be spoken into the public arena.”

Graber, who now works with Our Stories Untold, a Mennonite advocacy group focused on addressing sexualized violence within the church and its members, that also seeks to address the church’s heterosexism and suppression of LGBTQ members, also took exception with Swartzendruber’s citing of potential threats as a reason for opposing the show, saying that Mennonites had historically always faced up to violence without flinching.

“In the name of justice we will walk into anything violent,” she declared. “We don’t shirk from violence. Because we serve a higher calling than this world, we will walk into violence. We will be these voices, we will be these peace and justice people – until it’s our own little prejudices and bigotry. When it affects our own bigotry and prejudice then we say, ‘Oh, there might be violence, we’d better stop this.’ It would be like Martin Luther King saying there’s a threat of bombing here so we’re going to cancel church.”

* * *

Parks had cited his inspiration for producing and directing Corpus Christi at EMU as being a production of the play by 108 Productions, best known through their “I Am Love” efforts which subsequently became a documentary film, Corpus Christi: Playing With Redemption. I reached out to both Nic Arnzen and James Brandon, who are partners in 108, I Am Love and the film, which they directed, and reached Arnzen first.

Parks had cited his inspiration for producing and directing Corpus Christi at EMU as being a production of the play by 108 Productions, best known through their “I Am Love” efforts which subsequently became a documentary film, Corpus Christi: Playing With Redemption. I reached out to both Nic Arnzen and James Brandon, who are partners in 108, I Am Love and the film, which they directed, and reached Arnzen first.

When he described that close to half of their ongoing touring performances, now a decade old, are in church-related venues, I asked about how the play reached those communities. “We basically answer the call where people are eager to see it,” he said. “Invitations often come from some spiritual leaders who are eager to broaden the minds of their congregation.”

Arnzen said that while certain Christian denominations resist the play, that once the group is in a community, they always issue an invitation to the leaders of all area churches, noting that, “We’ve had 10 years of running the play with little or no protest.” He observed that they rarely hear back after sending invitations, but that, “We’re not bitter that they’re not reaching back. We respect people’s boundaries. If I don’t respect their boundaries, how can I ask them to respect mine?”

Arnzen spoke about the many misconceptions about the play among those who haven’t seen or read it, dating back to the original Manhattan Theatre Club production. While acknowledging that they play does have “some words in it, very real language” and estimated “the f-word” appears “22 times, I think,” he was quite clear in his feeling about the overall message of the play.

“I attest to the fact that this is a very respectful retelling of the Jesus story.”

As a side note, 108’s production of the play uses a mixed gender cast, as Parks planned to do at EMU.

* * *

From four performances to one to two to none, Corpus Christi was not seen on the EMU campus this past weekend. There was, on February 18, after Parks’s decision – before the university administration was going to make it for him, one last rehearsal of Corpus Christi. While there was no official invitation, but apparently the theatre was packed. It became, in Parks’s word, a sit-in.

Parks has been assured that the show’s suspension will not affect his academic record, that he will receive full credits for his work and will graduate on time. I wondered whether he wanted to try to present the show off-campus, out from under the school’s authority.

He said, “I have considered it and I have considered it. The thing that is stopping me is that I have 13 actors who have lived through the I have a cast that wasn’t included in the decision making. No one sat at the table with me, no one gave their voice to what did happen, should happen, what might happen and at the bottom of the totem pole was the Corpus Christi cast. Now we have some harm and trauma that has been done and I don’t want to lead made cast members back into the hurt and trauma because now this story has it. I’ve been trying to think about how you do that and still give care to actors and not exacerbate the entire problem?”

I asked Parks whether he has any regrets and he said no. “I got to do what I love and there was some controversy about it,” he declared. “That’s OK, because I’m a queer body and that’s OK because I’m used to controversy.”

The conversation on the campus has not ended, and indeed I am told that the school community is consumed by it. There will be a student assembly for further conversation tomorrow, February 26. What will Parks’s role be at that event?

“I was invited,” he said. “I want to be the gatekeeper of the story. I want the facts to be straight.” And then his voice trailed off, in the equivalent of a verbal shrug as to what else might happen.

I will add my voice to that conversation, to the extent this is read on the campus, to say that 1) contrary to an assertion in the school newspaper, Corpus Christi has been produced on college campuses, dating back to at least 2001, however I was not able to determine whether it had been done at any faith-based university; 2) Andrea Wenger’s statement that not even the theatre department had approved the play, when Parks’s project had been approved in the spring and he was working on a thesis that was ready when the university asked for it and had announced auditions through university channels, seems highly contradictory; 3) that while there have been protests and threats against productions of Corpus Christi, my research did not reveal any overt acts against productions, only threats, and canceling it on the grounds of threats, or imagined threats, is the equivalent of giving in to terrorists, and 4) if the Mennonite Church’s practice of discernment in regards to this play is to be complete and thorough, then the play should be seen, so all discussions are fully informed by production, not merely by reading the script, or worse, hearsay, because that is how plays are truly meant to be seen.

The Mennonite Church may be wrestling with whether to welcome LGBTQ members of their church, and Eastern Mennonite University, in their handling of Corpus Christi, has proven how urgent the need to address this actually is. As someone who believes in complete equality for all people, I’d just like to suggest they have a leader in their midst who can open eyes and change minds and do so with love, respect and care. His name is Christian Parks.

I will update, correct and amend this post if circumstances warrant.

February 24th, 2015 § § permalink

Last night, I was extremely flattered and honored to receive the second annual Dramatists Legal Defense Fund’s “Defender” Award, for my work on behalf of artists’ rights and against censorship. My remarks were fairly brief (I know a little something about brevity and awards presentations, even when there isn’t an orchestra to “play you off”), so for those who have expressed interest, or may be interested, here’s what I had to say, following a terrific and humbling introduction by playwright J.T. Rogers, my newest friend.

Last night, I was extremely flattered and honored to receive the second annual Dramatists Legal Defense Fund’s “Defender” Award, for my work on behalf of artists’ rights and against censorship. My remarks were fairly brief (I know a little something about brevity and awards presentations, even when there isn’t an orchestra to “play you off”), so for those who have expressed interest, or may be interested, here’s what I had to say, following a terrific and humbling introduction by playwright J.T. Rogers, my newest friend.

I feel as if this evening is a classic Sesame Street segment, because as I see my name alongside those of such great talents as Annie Baker, Jeanine Tesori, Chisa Hutchinson, Charles Fuller and my longtime friend Pete Gurney, I can’t help feeling that one of these things is not like the others, one of these things doesn’t belong, namely me.

That said: I am honored more than you can possibly know to receive this recognition from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund and the Dramatists Guild, because I have spent the better part of my life in the dark with your stories, your characters, your words and your music, and my life is so much better for it.

My efforts on behalf of artists rights and against censorship began, four years ago, in what I merely thought was one blog post among many. My awareness and understanding has evolved significantly over that time. I am asked sometimes why I think there is so much more censorship of theatre now, and I’m quick to say that I know this has been happening for years, for decades; all I have done is, perhaps, to make some people more aware of some of the incidents, and to try to address them in greater depth than they might have otherwise received.

I think the same is true of unauthorized alteration of your work, sad to say. All I’ve been able to do is call more attention to it, in the hope of warning people off from trying it ever again. It is an uphill battle.

I want to thank John Weidman, Ralph Sevush and everyone who is part of creating the DLDF for giving me this honor, and to thank the Guild for being my partner and for welcoming me as your partner in these efforts. I want to thank Sharon Jensen and the staff and board of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts for allowing me the latitude to address these situations as they have arisen in the 18 months I have been part of that essential organization. I want to thank David van Zandt, Richard Kessler and especially Pippin Parker for making it possible for me to professionalize this work as the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama; I look forward to working with all of you through that new platform. And I especially want to thank my wife, Lauren Doll, for so many things, not least of which has been tolerating the late night and early morning calls with strangers around the country, often high school students, and the furious typing at all hours, whenever someone reaches out to me about censorship or the abrogation of authors rights.

I accept this award less for myself than for the students, teachers and parents who stand up for creative rights, in places like Maiden, North Carolina; South Williamsport, Pennsylvania; Plaistow, New Hampshire; Wichita, Kansas; and Trumbull, Connecticut, among others. If they didn’t sound the alarm, we might otherwise never know.

I should tell you that when I’ve visited some of these communities, I have had people come up to me repeatedly and tell me that I am brave for doing this work. ‘But I’m not brave,’ I tell them, ‘You’re the brave ones. I have nothing at stake here. You do.’

Indeed, I am not brave. What I am is loud. I will shout on behalf of theatre, on behalf of arts education, on behalf of creative challenge, on behalf of all of you here and all of those artists who aren’t here for as long I have a voice. And those of you who know me are fully aware that it’s very hard to shut me up.

My congratulations to tonight’s other honorees and thank you again for this award.

February 13th, 2015 § § permalink

No, I’m sorry, it’s not a blog post; it’s a press release. But if you’ll read on, I hope you’ll understand why I’ve placed it here, and indulge me this once. – Howard

NEW YORK (February 12, 2014) – The New School for Drama (Pippin Parker, Director) announces the launch of the Arts Integrity Initiative, a new project aimed at supporting and protecting the work of artists at every level of society and production. Under the leadership of arts administrator, writer and advocate Howard Sherman, Arts Integrity will not only examine and take an active role in instances of censorship and alteration of works, but also serve as a resource for the academic and professional arts communities.

The program is designed to ensure that audiences and practitioners alike have the opportunity to engage directly with challenging, vital work that reflects the very best the arts have to offer.

The program is designed to ensure that audiences and practitioners alike have the opportunity to engage directly with challenging, vital work that reflects the very best the arts have to offer.

“As long as books are banned, creative works are rewritten, and plays and musicals are eliminated by schools because they deal with challenging issues, we need to be vigilant about protecting freedom of speech, quality education and the rights of artists,” said Richard Kessler, Executive Dean of The New School’s Performing Arts School and Dean of Mannes School of Music. “With this new program, The New School addresses the subject from multiple vantage points, developing students who understand the necessity of free artistic expression as a means by which to explore, reflect, and critique society.”

The program features new curricular opportunities for students that explore the value of free artistic expression, as well as enhanced community outreach and projects to confront the issue. These commitments will be amplified through a range of public programs to promote discourse on the silencing or manipulation of artistic works, copyright protection, and broader use of the arts as a vehicle for social engagement and justice.

Projects associated with the Office for Arts Integrity include integrated coursework in conjunction with a forthcoming Master’s degree in Arts Management and Entrepreneurship; a collective space for affected professional and community artists to raise concerns and seek guidance; an online publication chronicling challenges to artistic expression and offering original work speaking directly to those issues from within the New School community and expert outside voices; and public programs to raise awareness of the silencing of artistic works and devise strategies for mobilization of the creative and educational communities.

Projects associated with the Office for Arts Integrity include integrated coursework in conjunction with a forthcoming Master’s degree in Arts Management and Entrepreneurship; a collective space for affected professional and community artists to raise concerns and seek guidance; an online publication chronicling challenges to artistic expression and offering original work speaking directly to those issues from within the New School community and expert outside voices; and public programs to raise awareness of the silencing of artistic works and devise strategies for mobilization of the creative and educational communities.

“Since he first picked up the anti-censorship banner, no one has been a more vocal, tireless, and effective advocate for the playwright’s right to be heard than Howard Sherman,” said John Weidman, President of the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund.

“I began doing work in this area on an ad hoc basis four years ago,” said Sherman, “and since that time I’ve increasingly found the need for a proactive resource to study and address arts censorship, supporting both academic and professional arts companies in their efforts to do work that has the greatest rewards for their constituencies. At the same time, I find more and more examples of works being altered unilaterally to appease often arbitrary assessments of what is appropriate or acceptable – or even simply appealing.”

Sherman continued, “Too often when challenges arise, those who are targeted don’t know where to turn, and I hope we’ll be able to provide those facing such restriction or tampering with guidance and on the ground resources, as well as collaborate with other organizations which share those goals, while bringing specific arts expertise to the table. In addition, our plan is to explore the roots of these issues in the arts and work collaboratively within schools and both the amateur and professional communities to develop best practices to reduce these high profile incidents over time, even as we look to explore cases that never reach the general public.”

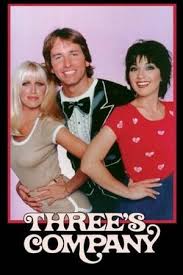

Recent examples of obstruction of artists’ rights include the ongoing lawsuit preventing production of David Adjmi’s dark parody 3C and the unauthorized alteration of the musical Hands on a Hardbody in its Texas premiere in Houston. Recent arts censorship efforts have included the cancelations of Almost, Maine in North Carolina and Spamalot in South Williamsport, Pennsylvania; and the cancelations and subsequent restorations of Rent in Trumbull, Connecticut and Sweeney Todd in Plaistow, New Hampshire.

Howard Sherman is senior strategy consultant at the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts, a position he’ll continue in parallel to his new role at The New School for Drama. Sherman has been executive director of the American Theatre Wing and the O’Neill Theatre Center, managing director of Geva Theater, general manager of Goodspeed Musicals and public relations director of Hartford Stage. He has recently been recognized as one of the National Coalition Against Censorship’s “Top 40 Free Speech Defenders of 2014” and will be honored later this month with The Dramatists Legal Defense Fund’s second “Defender” Award. His writing about the arts has been seen in such publications as American Theatre magazine, Slate and The Guardian, and he is the U.S. correspondent for London’s The Stage newspaper. He blogs at www.hesherman.com.

February 10th, 2015 § § permalink

Hannah Cabell and Anna Chlumsky in David Adjmi’s 3C at Rattlestick Playwrights Theater (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Seen any good productions of David Adjmi’s play 3C lately?

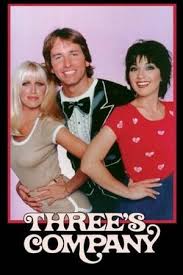

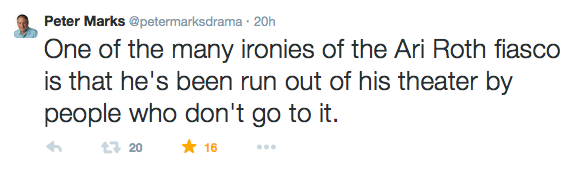

Sorry, that’s a trick question with a self-evident answer: of course you haven’t. That’s because in the two and a half years since it premiered at New York’s Rattlestick Playwrights Theater, no one has seen a production of 3C because no one is allowed to produce it, or publish it. Why, you ask? Because a company called DLT Entertainment doesn’t want you to.

3C is an alternate universe look at the 1970s sitcom Three’s Company, one of the prime examples of “jiggle television” from that era, which ran for years based off of the premise that in order to share an apartment with two unmarried women, an unmarried man had to pretend he was gay, to meet with the approval of the landlord. It was a huge hit in its day, and while it was the focus of criticism for its sexual liberality (and constant double entendres), it was viewed as lightweight entertainment with little on its mind but farce and sex (within network constraints), sex that never seemed to actually happen.

Looking at it with today’s eyes, it is a retrograde embarrassment, saved only, perhaps, by the charm and comedy chops of the late John Ritter. The constant jokes about Ritter’s sexual façade, the sexless marriage of the leering landlord and his wife, the macho posturings of the swinging single men, the airheadedness of the women – all have little place in our (hopefully) more enlightened society and the series has pretty much faded from view, save for the occasional resurrection in the wee hours of Nick at Night.

In 3C, Adjmi used the hopelessly out of date sitcom as the template for a despairing look at what life in Apartment 3C might have been had Ritter’s character actually been gay, had the landlord been genuinely predatory and so on. It did what many good parodies do: take a known work and turn it on its ear, making comment not simply on the work itself, but the period and attitudes in which it was first seen.

Enter DLT, which holds the rights to Three’s Company. They sent a cease and desist letter to Adjmi back in 2012 claiming that the show violated their copyright; Adjmi said he couldn’t afford to fight it. Numerous well-known playwrights wrote a letter in support of Adjmi and the controversy generated its first wave of press, including pieces in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Over time, there have been assorted legal filings by both parties, with another wave of press appearing last year just about this time, when Adjmi sued for the right to reclaim his play for production, with commensurate press coverage once again from the Times and Studio 360, among others.

Enter DLT, which holds the rights to Three’s Company. They sent a cease and desist letter to Adjmi back in 2012 claiming that the show violated their copyright; Adjmi said he couldn’t afford to fight it. Numerous well-known playwrights wrote a letter in support of Adjmi and the controversy generated its first wave of press, including pieces in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Over time, there have been assorted legal filings by both parties, with another wave of press appearing last year just about this time, when Adjmi sued for the right to reclaim his play for production, with commensurate press coverage once again from the Times and Studio 360, among others.

Why do I dredge this all up now? Because the bottom line is that DLT is doing its level best to prevent a playwright from earning a living, and throwing everything they can into a specious argument to do so. They say, both in public comments and in their filings, that 3C might confuse audiences and reduce or eliminate the market for their own stage version (citing one they commissioned and one for which they granted permission to James Franco). They cite negative reviews of 3C as damaging to their property. And so on.

But while I’m no lawyer (though I’ve read all of the pertinent briefs on the subject), I can make perfect sense out of the following language from the U.S. Copyright Office, regarding Fair Use exception to copyright (boldface added for emphasis):

The 1961 Report of the Register of Copyrights on the General Revision of the U.S. Copyright Law cites examples of activities that courts have regarded as fair use: “quotation of excerpts in a review or criticism for purposes of illustration or comment; quotation of short passages in a scholarly or technical work, for illustration or clarification of the author’s observations; use in a parody of some of the content of the work parodied; summary of an address or article, with brief quotations, in a news report; reproduction by a library of a portion of a work to replace part of a damaged copy; reproduction by a teacher or student of a small part of a work to illustrate a lesson; reproduction of a work in legislative or judicial proceedings or reports; incidental and fortuitous reproduction, in a newsreel or broadcast, of a work located in the scene of an event being reported.”

As someone who has gone out on a limb at times defending copyright and author’s rights, I’d be the first person to cry foul if I thought DLT had the slightest case here. But 3C (which I’ve read, as it’s part of the legal filings on the case) is so obviously a parody that DLT’s actions seem to be preposterously obstructionist, designed not to protect their property from confusion, but to shield it from the inevitable criticisms that any straightforward presentation of the material would now surely generate.

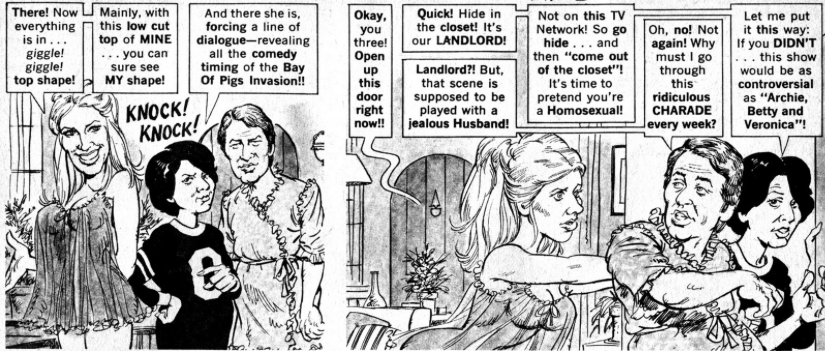

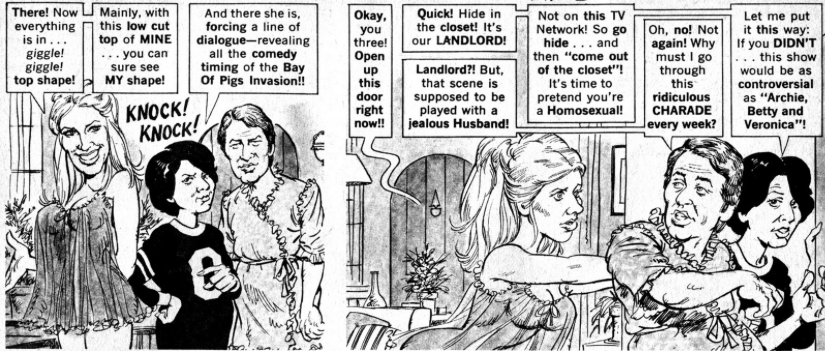

Rather than just blather on about the motivations of DLT in preventing Adjmi from having his play produced and published, let me demonstrate that their argument is specious. To do so, I offer the following exhibit from Mad Magazine:

What’s fascinating here is that Mad, a formative influence for countless youths in the 60s and 70s especially, parodied Three’s Company while it was still on the air, seemed to already be aware of the show’s obviously puerile humor, was read in those days by millions of kids – and wasn’t sued for doing so. That was and is a major feature of Mad, deflating everything that comes around in pop culture through parody. The fact is, Adjmi’s script is far more pointed and insightful than any episode of Three’s Company and may well work without deep knowledge of the original show, just like the Mad version.

The most recent filing in the Adjmi-DLT situation comes from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, an offshoot of The Dramatists Guild. Like all of the filings in this case, it’s very informative about copyright in general and parody in particular, and it spells out the numerous precedents where the use of a prior work was permitted under fair use, with particular attention to the idea that when the new work is transformative – which 3C surely is – it is permitted (read the complete amicus curiae brief here). In addition to their many examples, I would add from my own misspent youth such works as Bored of the Rings, a 1969 book-length parody of Tolkien by some of the people who would go on to create the National Lampoon, where incidentally, DLDF president John Weidman exercised his own comic skills) and Airplane!, which took its plotline (and punctuation mark) of a poisoned airline crew directly, uncredited, from the 1957 film Zero Hour! More recently, the endlessly touring Potted Potter has successfully run without authorization, though clearly derived from the works of J.K. Rowling and prior to any authorized stage interpretation.

The most recent filing in the Adjmi-DLT situation comes from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, an offshoot of The Dramatists Guild. Like all of the filings in this case, it’s very informative about copyright in general and parody in particular, and it spells out the numerous precedents where the use of a prior work was permitted under fair use, with particular attention to the idea that when the new work is transformative – which 3C surely is – it is permitted (read the complete amicus curiae brief here). In addition to their many examples, I would add from my own misspent youth such works as Bored of the Rings, a 1969 book-length parody of Tolkien by some of the people who would go on to create the National Lampoon, where incidentally, DLDF president John Weidman exercised his own comic skills) and Airplane!, which took its plotline (and punctuation mark) of a poisoned airline crew directly, uncredited, from the 1957 film Zero Hour! More recently, the endlessly touring Potted Potter has successfully run without authorization, though clearly derived from the works of J.K. Rowling and prior to any authorized stage interpretation.

It’s been months since there have been filings for summary judgment in the case (August 2014, to be precise), and according to Bruce Johnson, the attorney at Davis Wright Tremaine in Seattle who is leading the fight on Adjmi’s behalf, there is no precise date by which there will be a ruling. Some might say that I’m essentially rehashing old news here, but I think it’s important that the case remains prominent in people’s minds, because it demonstrates the means by which a corporation is twisting a provision of copyright law to prevent an artist from having his work seen – and that’s censorship with a veneer of respectability conferred by legal filings under the umbrella of commerce. There may be others out there facing this situation, or contemplating work along the same lines, and this case may be suppressing their work or, depending upon the ultimate decision, putting them at risk as well.

We don’t all get to vote on this, unfortunately. But even armchair lawyers like me can see through DLT’s strategy. I just hope that the judge considering this case used to read humor magazines in his youth, which should provide plenty of precedent above and beyond what’s in the filings. 3C may take a comedy and make it bleak, but there’s humor to be found in DLT’s protestations, which are (IMHO) a joke.

P.S. I don’t hold the copyright to any of the images on this page. I’m reproducing them under Fair Use. Just FYI.

January 21st, 2015 § § permalink

There were, in my estimation, many interesting people at the first performance of Almost, Maine in Hickory NC this past Thursday night.

Almost, Maine program cover for Hickory NC

To begin with, there was the author, John Cariani, who had come out to support the production, something he can’t do very often given how frequently his show is produced around the country. There was Jack Thomas, who produced the New York City premiere of Almost, Maine a decade ago. There was the doctor who had helped to found OutRight Youth of Catawba Valley, a support center for LGBTQ young people in this rural North Carolina region, which the performances, in part, benefited. There were the two women who were part of the local “Friends of the Library,” who knew little of the show but just wanted to support the effort. There was a high school drama teacher from the Raleigh-Durham area who had driven two and a half hours to see the show – and had to drive home that very night.

Oh, and there was the guy out on the street as I entered the building who was carrying a cross and shouting about how we were all going to hell for supporting homosexuality, and that God had very specific intentions for how humans should use their genitalia in relation to one another – though he was somewhat less circumspect than I just was in his phrasing.

Blake Richardson and Jonathan Bates in the scene “They Fell” from Almost, Maine

This production of Almost, Maine in Hickory was originally to have been produced at Maiden High School in nearby Maiden NC, but the show was canceled, after rehearsals had begun, when the school’s principal buckled to complaints about gay content and sex outside of marriage, reportedly from local churches (one made itself known publicly shortly before performances began). Due to the determination of Conner Baker, the student who was to have directed the show at the high school and ended up performing and co-directing, and with the tireless support of Carmen Eckard, a former teacher who had known many of the students since she taught them in elementary school, the show was shifted to Hickory, where it was performed in the community arts center’s auditorium.

Ci-Ci Pinson and Nathaniel Shoun in “Where It Went” from Almost, Maine

There were shifts in casting due to schedule changes, due to the show no longer being school-sanctioned, due to the need to travel 15 miles or so to and from Maiden to Hickory. But nine young people, a mix of current and former Maiden High students and a few students from local colleges, made sure that Catawba County got to see Almost, Maine, the sweet, rueful comedy that is hardly anyone’s idea of dangerous theatre.

Save for Cariani and Thomas, I hadn’t anticipated knowing anyone at the show that evening, though I had been in communication with Eckard and Baker since the objections first arose at Maiden High. But I was very pleased to spot Keith Martin, the former managing director of Charlotte Repertory Theatre, now The John M. Blackburn Distinguished Professor of Theatre at Appalachian State University, who I knew from my days as a manager in LORT theatre, but hadn’t seen or spoken with in more than a decade. Keith’s presence had a special resonance for me, because nearly 20 years ago, before the cast of Almost, Maine was born, he had been at the center of one of the most significant and ugly efforts to censor professional theatre in that era, namely community and political campaigns to shut down Charlotte Rep’s production of Angels in America, a national news story at the time which saw lawsuits, injunctions, restraining orders and even the de-funding of the entire Charlotte Arts Council, all in an effort to silence Tony Kushner’s “Gay Fantasia on National Themes.” The efforts failed, but left scars.

Keith Martin

I spoke with Keith a few nights after we saw Almost, Maine, and even as he recounted – and I recalled – the fight over Angels, he told me of two other censorship cases in North Carolina in the 1990s. The first, with which I was familiar and which played out over much of the decade, began in 1991, when a teacher named Peggy Boring was removed from her school and reassigned due to her choice of Lee Blessing’s play Independence for students, which was deemed inappropriate by administrators. Boring didn’t accept the disciplinary action and brought suit against the school system, which went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ultimately let stand a lower court decision which said that Boring’s right to free expression did not extend to what she chose for her students, an key precedent for all high school theatre and education.

The second occurrence which Keith told me about took place in 1999, when five young playwrights won a playwriting contest at the Children’s Theatre of Charlotte – but only four of the pieces were produced. The fifth, Samantha Gellar’s Life Versus the Paperback Romance, was omitted to due its inclusion of lesbian characters. The play was ultimately produced locally under private auspices and also got a reading at The Public Theater in New York with Mary-Louise Parker and Lisa Kron in the cast, but in the wake of the Boring case and Angels in America, it couldn’t be seen in North Carolina in a public facility or produced using public funds.

As we talked, as he told me firsthand accounts of situations both known and unknown to me, Keith was very concerned that I might focus too much on him when I sat down to write. It’s hard not to want to tell his story – or, perhaps, his stories – in greater detail. But since we both went to Hickory to celebrate Almost, Maine and the people who made it happen, here’s just a handful of the very smart and pertinent thoughts he shared.

Why had he made the hour-long trip to Hickory? Because, he replied, “When one of us is threatened, we as a theatre community are all at risk.”

Why is this important even in high school? “Teenagers aged 13 to 17 are, I believe, among the most marginalized voices in America today,” said Martin. “It’s ironic, because they’ve developed a sense of place, they have a spirit of activism, but they’re not yet of a legal age to give voice to their passion.”

Regarding efforts to minimize controversy in theatre production, Keith said, “Theatre has always been the appropriate venue for the discussion of difficult subjects and it provides a respectful place where people of goodwill who happened to disagree about different sides of an issue can see that issue portrayed on stage and then have a healthy, informed debate.

Is there something special about North Carolina that led to these high profile cases emerging from the state? “Angels in America was portrayed as having happened in a southern, bible belt town. But what happened after that?” Keith asked me, going on to cite the controversies and attempts to silence Terrence McNally’s Corpus Christi at Manhattan Theatre Club and My Name is Rachel Corrie at New York Theatre Workshop.

The team behind Almost, Maine in Hickory NC, including playwright John Cariani

As I said at the beginning, there were many interesting people at the opening of Almost, Maine. I suspect the students in the show didn’t know, or even know of, Keith Martin, and this post is one small way of putting their work in a broader context that he embodies in their state. I have no doubt that there were other people with personal experiences and connections relating to what the students had achieved, and it’s pretty much certain that neither they nor I will ever know them fully. But just as Keith said to me in our conversation that, “these kids need some recognition that their efforts have not gone unheard,” it’s important that they know that their theatrical act of civil disobedience does not stand alone, be it in North Carolina or nationally. The same is true for everyone who had a hand in making certain that Almost, Maine was heard over the cries of those who wanted it silenced.

In one of my early conversations with Conner Baker, as we discussed her options, her mantra was that, “We just want to do the play.” She and her classmates and supporters did just that, in the least confrontational way possible, but in doing so their names belong alongside those of Peggy Boring, Samantha Gellar, Keith Martin and many others in the annals of North Carolina theatre, at the very least.

I’ll leave you with one last connection between Keith Martin and Almost, Maine. The SALT Block Auditorium where the show was produced is located in an arts center which is the former Hickory High School. Keith Martin attended that very school decades ago and performed on the stage where Almost, Maine was produced last week. The role he recalled for me when asked? The title character in The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. I suspect that even James Thurber’s famous daydreamer couldn’t have imagined the controversy surrounding Almost, Maine…or its happy ending. Maiden’s reactionary, cowardly loss was Hickory’s heroic gain.

January 6th, 2015 § § permalink

“What’s the deal with all this high school theatre?”

That’s the kind of comment—spoken, written or tweeted—I’ve been getting regularly over the past four years since I began writing about instances of censorship of theatre in American high schools (and, on occasion, colleges). To be fair to those who may be skeptical about the extent of the problem, I myself have been surprised by the volume and variety of issues raised over the content of shows being done—and, in some cases, ultimately not being done—in school-sponsored theatre.

But between writing about these incidents, and directly involving myself as an advocate in some of them, I’ve come to believe that what’s taking place in our high schools and on our campuses has a very direct connection to what is happening (and will be happening) on professional stages.

So here are nine common questions that have arisen as my advocacy has increased, and some answers—although, as every attempt at censorship is different, there aren’t any absolute answers.

1. Why is there so much more censorship of high school theatre these days?

There’s no quantitative study that indicates the policing of what’s performed is any greater than it was 10, 25 or 50 years ago. Everything is anecdotal. But the Internet has made it easier for reports to spread beyond individual communities and for news-aggregation sites uncover and accelerate the dissemination of such stories. It only takes one report in a small-town paper these days to bring an incident to national attention; that was a rarity in the print-only era.

2. Isn’t this just a reflection of our polarized national politics?

School theatre censorship doesn’t necessarily follow the red state/blue state binary division, because the impulse can arise from any constituency. While efforts to quash depictions of LGBTQ life—as with Almost, Maine in Maiden, N.C., or Spamalot in South Williamsport, Pa.—may be coming from political constituencies galvanized against the spread of marriage equality, or from certain faith communities which share that opposition, that’s hardly the only source. Opposition to Sweeney Todd, both muted (in Orange, Conn.) and explicit (in Plaistow, N.H.) was driven by concern about the portrayal of violence in an era of school shootings and rising suicide rates, while Joe Turner’s Come and Gone was challenged by a black superintendent over August Wilson’s use of the “n-word.”

3. What’s the real impact of school theatre on the professional community?

The Broadway League pegs attendance at Broadway’s 40 theatres in the neighborhood of 13 million admissions a year and touring shows at 14 million a year. TCG’s Theatre Facts reports resident and touring attendance of 11 million. That totals a professional universe of 38 million admissions.

Based on figures provided to me by half a dozen licensing houses, there are at minimum 37,500 shows done in high school theatres annually, and conservatively guesstimating three performances of each in 600 seat theatres at 75-percent capacity, that’s more than 50 million attendees. In both samples, the numbers don’t represent the total activity, but high school theatre’s audience impact is undeniable, both as a revenue stream for authors and as a means of reaching audiences who might not see any other theatre at all.

4. Does it really matter what shows kids get to do in high school?

While there are valuable aspects to making theatre that apply no matter what the play choice may be, many schools view their productions as community relations, frequently citing that they want to appeal to audiences “from 8 to 80.” While the vast majority of students in the shows, and their friends who come to see them, will never become arts professionals, they are the potential next generation of audiences and donors for professional companies. If they are raised on a diet of Alice in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz (both currently very popular in the high school repertoire), how can we expect more challenging work , new work, or socially conscious work to sustain itself 20 years on?

5. Are school administrators fostering an environment in which censorship flourishes?

I’m unwilling to accept the idea that our schools are run by people who fundamentally want to limit what students can learn—or perform. But they are operating within a political structure topped by an elected board of education, and can be subject to political pressure that often makes the path of least resistance—altering text or changing a selected show, in most cases—the expedient way to go. Unless an administrator (or a teacher, for that matter) is independently wealthy, they can’t necessarily afford to risk their job fighting for the school play that may have challenging content. That said, students at Newman University rebelled against administration-dictated text changes, reverting to the script as written for the latter two of their four performances of Legally Blonde in November.

6. Isn’t this a free speech issue?

In a word, no. Schools have the right and responsibility to determine what is appropriate activity and speech under their control, and just because students are exposed to all manner of content in the media and even in their day-to-day lives doesn’t mean that schools can or must permit it, either in classrooms or performance. That The Crucible is in countless high school curriculums does not necessarily prevent it from being censored as a performance piece, despite the seeming double standard.

The same stringent oversight that affects school theatre is also often directed at school newspapers and media. However, while some school systems attempt to control all student speech, it is a First Amendment violation to infringe on student speech to the media about their dissatisfaction with the actions of a school, including censorship. Drama teachers, who are best equipped to make the cases for the shows they choose, are usually prevented from doing so by employment agreements which prohibit them from discussing school matters without the express approval of the administration, typically the superintendent.

7. Don’t shows get edited all the time in schools for content?

In all likelihood, shows are constantly being nipped and tucked by teachers and administrators to conform to their perception of “community standards,” whether it’s the occasional profanity or entire songs. But that doesn’t make it right, and it is censorship. Aside from violating copyright laws and the licensing contracts signed for the right to the show, it sets a terrible example for students by suggesting that authors’ work can be altered at will, undermining the rights of the artists who created the work.

Some writers and composers have authorized school editions or junior versions of their shows for the school market to recognize frequent concerns and to keep from denying students the opportunity to explore their shows. But the rights must lie with the authors, not each and every school. If that isn’t made clear early on, how can we expect to fight censorship anywhere?

8. When a show is canceled and then successfully restored through a public campaign, is that winning the battle and then losing the war?

That’s a genuine concern of mine—that once there’s a public battle over theatrical content, the school will thereafter clamp down even harder and apply greater scrutiny forever after to drama programs, academic or extracurricular. At the Educational Theatre Association’s national conference this past summer, one attendee asked the others if there were shows that they believed would be great for their students but which they couldn’t even raise as possibilities. Every single teacher in the room raised his or her hand. So the incidents that become public—ones in which a show is announced, then has approval rescinded—are the tip of the iceberg. Drama teachers and directors are already having their choices limited, often by self-censorship. There’s much more work to be done, but if blatant examples don’t come to light, it may never be possible to galvanize support for school theatre that challenges students to do great work and great works.

9. Can professional artists and companies make any difference when incidents of censorship arise?

Local theatres—professional, community and academic—make superb allies in fighting against censorship. Institutions and individuals within communities that are respected for their art occupy a position from which to speak out forcefully and effectively for school theatre programs. Whether it’s a nearby artistic director or a one-time resident who has gone on to a professional career, they bring a history and authority that will speak to both the local populace and the media. The vocal support of the Yale School of Drama and Yale Rep with the aforementioned Joe Turner, and of Goodspeed Musicals and Hartford Stage in the case of Rent in Trumbull, Conn., were key factors in the ultimately successful efforts toward restoring those shows to production.