September 15th, 2015 § § permalink

Please consider the following two statements.

- In a description of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado: “The location is a fictitious Japanese town.”

- “There are no ethnically specific roles in Gilbert and Sullivan.”

The conflict between these two statements seems fairly obvious since even in a fictitious Japanese village, the residents are presumably Japanese, and that is indeed ethnically specific, even if they are endowed with nonsensical names that may have once sounded vaguely foreign to the British upper crust.

The NYGASP Production of The Mikado

Now one could try to explain away this dissonance by saying that the statements are drawn from conflicting sources, however they are both taken from the website of the New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players. The company, which has been producing the works of G&S in Manhattan for 40 years, will be mounting their production of The Mikado at NYU’s Skirball Center from December 26 of this year through January 2, 2016, six performances in total.

It is hardly news that The Mikado is a source of offense and insult to the Asian-American community, both for its at best naïve and at worst ignorant cultural appropriation of 19th century Japanese signifiers, as well as for the seeming intransigence of 20th and 21st century producers when it comes to attempting to contextualize or mitigate how the material is seen today. Particularly awful is the ongoing practice of utilizing yellowface (Caucasian actors made up to appear “Asian”) in order to produce the show, instead of engaging with Asian actors to both reinterpret and perform the piece. Photos of past productions by the NY Gilbert & Sullivan Players suggest their practice is the former.

“History!,” some cry, “Accuracy to the period!” That’s the same foolish argument recently spouted by director Trevor Nunn to explain why his new production of Shakespeare history plays featured an entirely white cast of 22. “But The Mikado is really not about Japan! It’s a spoof of British society,” is another defense. But it has been some 30 years since director Jonathan Miller stripped The Mikado of its faux Japanese veneer and made it quite obviously about the English, banishing the “orientalist” trappings from 100 years earlier. Besides, reviews of prior NY Gilbert & Sullivan Players productions note that the script is regularly updated with topical references germane to the present day, so claims to historical accuracy have already been tossed away.

Looking at the New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players (NYGASP) cast on their website, it appears that the company is almost exclusively white. While our increasingly multicultural society makes it difficult and reductive to assume race and ethnicity based on names and photos, I noted a single person who I would presume to be Latino among the 70 photos and bios, and seemingly no actors of Asian heritage. While I should allow for the possibility that there may be new company members to come, it seems clear that the preponderance of The Mikado company will be white.

Was it only a year ago that editorial pages and arts pages erupted over a production of The Mikado in Seattle precisely because of an all-white cast? Is it possible that in the insular world of Gilbert and Sullivan aficionados, word didn’t reach the founder and artistic director of NYGASP, Albert Bergeret? I doubt it. In Seattle, the uproar was sufficient to warrant a gathering of the arts community to air grievances and discuss the lack of racial and ethnic awareness shown by the Seattle troupe. That it followed on another West Coast controversy, a La Jolla Playhouse production of The Nightingale, a musical adaptation of a China-set Hans Christian Andersen tale that utilized “rainbow casting,” rather than ethnically specific casting, only added fuel to the justifiable controversy.

This year, The Wooster Group sparked protest on both coasts with its production of Cry Trojans, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida that had members of an all-white company in redface portraying Native Americans and appropriating Native American culture, as viewed through the wildly inaccurate prism of American western movies. Yet in a victory for ethnically accurate casting earlier this year, a major Texas theatre company recast its leading actor in The King and I when it was made abundantly clear by the Asian American theatre community that a white actor as the King of Siam simply wasn’t acceptable.

The NYGASP production of The Mikado (photo by William Reynolds)

That NYGASP will be performing on the NYU campus makes the impending production all the more surprising. It is highly doubtful that the university’s arts programs would undertake an all-white Mikado any more than they would do an all-white production of Porgy and Bess (although copyright probably prevents them from attempting the latter). College campuses are where racial consideration is at the forefront of thinking and action. Is it possible that The Mikado is in the Christmas to New Year’s slot precisely because school will not be in session and the university will be largely vacant, mitigating the potential for protest? Without school in session, NYGASP can’t even take advantage of the university community, if both parties agreed, to contextualize this production as part of a broader cultural conversation, not to explain it away, but to interrogate the many issues it raises.

“We can’t find qualified performers in the Asian-American community,” is another one of the frequent defenses of yellowface Mikados. After 25 years of countless productions of Miss Saigon, a revised Flower Drum Song with an entirely Asian-American cast, and two current Broadway productions (The King and I and the impending Allegiance) with largely Asian casts, it’s not possible to claim that the talent isn’t out there. Excuses about training or worse, diction (which is noted on the NYGASP site), are utterly implausible.

Admittedly, even with racially authentic casting, The Mikado is a problematic work, since it is rooted in ignorant stereotypes of Japan and not in any real truth. Does that make it unproducible, like, say The Octoroon (as explored by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s revisionist An Octoroon), or any number of early musical comedies which traded in now-offensive racial humor? No, as Jonathan Miller proved 30 years ago. And while it seems contradictory, even if the text and characterizations of The Mikado are retrograde, if it is to be done, at least it should be interpreted by Asian actors, who are afforded too little opportunity in theatre, musical theatre, operetta and opera as it is. There are any number of Asian performers who will discuss their reservations about Miss Saigon as well, but at least it affords them work, and the chance to bring some sense of nuance and authenticity to the piece. The same should be true of The Mikado.

The upset surrounding The Mikado at the Skirball Center has just begun to bubble up, originating so far as I saw with Facebook posts from Leah Nanako Winkler, Ming Peiffer, and Mike Lew; Winkler has already posted a blog in which she speaks candidly with NYGASP’s Bergeret and Erin Quill has a strong take as well. Hopefully a great deal more will be said, with the goal that instead of keeping The Mikado trapped in amber as G&S loyalists seem to prefer, it will be brought properly into the 21st century if it is to be performed at all. In a city as large as New York, maybe there are those who see six performances of The Mikado as being insignificant and not worthy of attention. But in a city as modern and multicultural as New York, can and should a yellowface, Causcasian Mikado be countenanced? Now is the time for the last (ny)gasp of clueless Mikados.

Update, September 16, 2 pm: NYGASP has replaced the home page of their website with a statement titled, “The Mikado in the 21st Century.” It reads in part:

Gilbert studied Japanese culture and even brought in Japanese acquaintances to advise the theater company on costumes, props and movements. In its formative years, NYGASP similarly engaged a Japanese advisor, the late Kayko Nakamura, to ensure that our costumes and sets remain true to the spirit of the culture that inspired them. We are dedicating this year’s production of The Mikado to her memory.

One hundred and forty years after the libretto was written, some of Gilbert’s Victorian words and attitudes are certainly outdated, but there is vastly more evidence that Gilbert intended the work to be respectful of the Japanese rather than belittling in any way. Although this is inevitably a subjective appraisal, we feel that NYGASP’s production of The Mikado is a tribute to both the genius of Gilbert and Sullivan and the universal humanity of the characters portrayed in Gilbert’s libretto.

In all of our productions, NYGASP strives to give the actors authentic costumes and evocative sets that capture the essence of a foreign or imaginary culture without caricaturing it in any demeaning or stereotypical way. Lyrics are occasional altered to update topical references and meet contemporary sensibilities; makeup and costumes are intended to be consistent with modern expectations.

Update, September 16, 4 pm: Since I made the original post yesterday, several other pertinent blog posts have appeared, and I wanted to share them as well. There are many aspects to this conversation.

From Ming Peiffer, “#SayNoToMikado: Here’s A Pretty Mess.”

From Melissa Hillman, “I Get To Be Racist Because Art: The Mikado.”

From Chris Peterson, “The Mikado Performed In Yellowface and Why It’s Not OK.”

From Barb Leung, “Breaking Down The Issues with ‘The Mikado’”

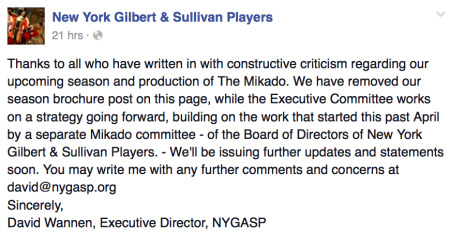

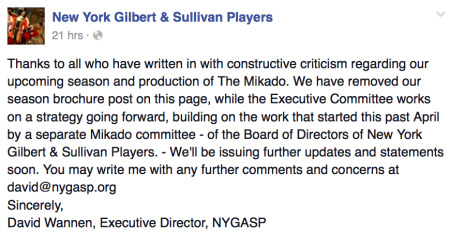

Update, September 17, 7 am: NYGASP has posted the following message on their Facebook page:

Update, September 18, 8 am: Overnight, NYGASP announced that they are canceling their production of The Mikado at the Skirball Center, replacing it with The Pirates of Penzance. A statement on their website reads as follows:

New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players announces that the production of The Mikado, planned for December 26, 2015-January 2, 2016, is cancelled. We are pleased to announce that The Pirates of Penzance will run in it’s place for 6 performances over the same dates.

NYGASP never intended to give offense and the company regrets the missed opportunity to responsively adapt this December. Our patrons can be sure we will contact them as soon as we are able, and answer any questions they may have.

We will now look to the future, focusing on how we can affect a production that is imaginative, smart, loyal to Gilbert and Sullivan’s beautiful words, music, and story, and that eliminates elements of performance practice that are offensive.

Thanks to all for the constructive criticism. We sincerely hope that the living legacy of Gilbert & Sullivan remains a source of joy for many generations to come.

David Wannen Executive Director New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players

Update, September 18, 3 pm: The NYGASP production of The Mikado was scheduled to be given a single performance on the campus of Washington and Lee University this coming Monday evening, September 21. As of this afternoon, the production has been replaced with the NYGASP production of The Pirates of Penzance.

* * *

Howard Sherman is the interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts.

June 22nd, 2015 § § permalink

“You can’t draw sweet water from a foul well,” critic Brooks Atkinson wrote of his initial reaction to the musical Pal Joey. I don’t know whether Christopher Hart of The Sunday Times in London knows this famous quote, but it certainly seems to summarize his approach to reviewing the London premiere of Stephen Adly Guirgis’s The Motherfucker With The Hat, which one can safely say is light years more profane than the Rodgers and Hart musical.

Alec Newman, Ricardo Chavira & Yul Vázquez in The Motherfucker With The Hat at the National Theatre

“A desperately boring play,” “an absolute stinker of a play,” “untrammelled by such boring bourgeois virtues as self-restraint or good manners,” “turgid tripe,” and “a pile of steaming offal,” are among the phrases Hart deploys about Guirgis’s Hat. While I happen to not agree with him (and admittedly I saw the Broadway production, not the one on at the National Theatre), he is entitled to these opinions. It may not be particularly nuanced criticism, but it’s his reaction. There are other British critics with opposing views (The Guardian and The Independent), and some who agree (Daily Mail), so there’s no consensus among his colleagues. But within his flaying of the play, Hart reveals classist, racist and nationalist sentiments that, however honestly he may be expressing them, prove why he is unable to assess the play on its own terms, empathizing with its flawed characters, as any good critic should endeavor to do.

Take this example: “Like the white working class in this country, the PRs in America have picked up a lot of black patois.” Even allowing for differences in language between England and the U.S., referring to residents of Puerto Rico and “the PRs” is patently offensive, and also hopelessly out of date, all at once. The statement also suggests that Puerto Ricans are in some way foreign, when the island itself has been part of America for more than a century; it’s perhaps akin to saying “the Welsh in Great Britain” as if they’re alien. When he parses “black patois” as the difference between saying “ax instead of ask,” Hart presents himself as Henry Higgins of American pronunciations, which I strongly suspect he picked up from watching American television and film, without any real understanding of racial culture or linguistics here – and he generalizes condescendingly about a huge swath of the British populace for good measure.

Hart also refers to the “very brief entertainment to be had in trying to work out” the ethnic background of the character Veronica, first musing that she might be “mixed race African American” but acknowledging her as Puerto Rican “when her boyfriend calls her his ‘little taino mamacita’.” I don’t know why he was fixated on this issue, presumably based on a parsing of the skin color of the actress in the role, especially since the play provided him with the answer (though the same problem has afflicted U.S. critics encountering Puerto Rican characters as well). Would that he were more focused on the character and story. He briefly describes the plot as being about “one Veronica, who lives in a scuzzy apartment off Times Square, snorts coke and sleeps around. Oh, and she shouts a lot.” In point of the fact, the play is an ensemble piece, and if any one character dominates, it’s Jackie, the ex-con struggling to fight his addictions and set his life straight.

After going off on a tear about the play’s profanity, Hart makes a comment about the play’s dialogue, saying, “A lot of it is ass-centred, in that distinctive American way.” As an American, I have to say that I’m unfamiliar with our bum-centric obsession, outside of certain pop and rap songs, even if Meghan Trainor is all about that bass. But hey, I’ve only lived here my whole life, and spent 13 of those years living and working in New York, a melting pot of culture and idiom. What do I know?

I don’t happen to read Hart with any regularity, but my colleague at The Stage, Mark Shenton, has noted his tendency to antagonistic hyperbole in the past, having called Hart out for separate reviews of Cabaret and Bent which both seem puritanical and, in the latter case, homophobic. While I peruse a number of UK papers online, both via subscription and free access, even my limited exposure to Hart’s rhetoric suggests that The Sunday Times is an outlet whose paywall I shall happily leave unbreached.

I was actually going to shrug off the ugliness of the Hat review, but only about an hour after I read it, I came across some letters to the editor in The Boston Globe, responding to a review of A. Rey Pamatmat’s Edith Can Shoot Things and Hit Them at Company One Theatre. While I don’t think the critic in this case, Jeffrey Gantz, was trying to be inflammatory (as I’m fairly certain Hart was), he revealed his own biases in seemingly casual remarks. Noting that two of the characters are Filipino-American, he wrote:

They make the occasional reference to their favorite Filipino dishes, but I wish more of their culture was on display, and it seems odd that they have no racial problems at school.

Maria Jan Carreon and Gideon Bautista in Edith Can Shoot Things and Hit Them at Company One Theatre

Not every character with a specific racial or ethnic origin need demonstrate it for our consumption on stage; it may not be germane to the play or perhaps the characters created by Pamatmat are more steeped in American culture than Filipino. The statement is the equivalent of saying about me, were I a character, that though I mention matzoh ball soup and pastrami, it would be nice if I spoke more Yiddish, wore a yarmulke, or waxed rhapsodic about my bar mitzvah. My grandparents were all immigrants to the U.S., so I’m only second generation American, not so far removed from another culture and schooled at length in my religion, but I don’t constantly remind people of those facts.

As for not experiencing intolerance at school, Gantz must have a singular idea of what every young person who is not white experiences on a daily basis. That’s not to say that there isn’t ugliness and ignorance directed at people of color far too regularly at every level of American life, but perhaps that isn’t germane to the story Pamatmat wants to tell or part of the personal experience he draws upon (he’s from Michigan, incidentally). It’s not as if “racial problems” for students of color are an absolute rule of dramaturgy that must be obeyed.

That said, it’s ironic that Gantz criticizes the play for taking on “easy targets, notably bigotry and bad parents.” The fraught relationship between parents and children has been the fodder of drama since the Greeks, and it seems an endlessly revelatory subject; as for bigotry, if it is perceived as an “easy” subject, then perhaps Gantz, despite wishing “racial problems” on the characters, has no real understanding of the complexity of race in America and the many forms bigotry can take, enough to fuel 1,000 plays and playwrights or more. But he’s complaining that Pamatmat hasn’t written the play that Gantz wants to see, rather than assessing the one that was written.

I can’t speak to the general editorial slant of The Sunday Times, so while Hart’s recent rant may be in keeping with the paper’s character, I don’t think the implicit racial commentary of Gantz’s review is consistent with the social perspective of The Boston Globe. That leads me to wonder, as I have before, what role editors play when racial bias appears in reviews, such as in a Chicago Sun-Times review that appeared to endorse racial profiling. Yes, these reviews are each expressions of one person’s opinion, but they are also, by default, opinions which are tacitly endorsed by the paper itself. Reading these reviews just after following reports from the Americans in the Arts and Theatre Communications Group conferences, which demonstrated a genuine desire on the part of arts institutions to address diversity and inclusion, I worry that if the arbiters of art continue to judge work based on retrograde social views, it will only slow progress in the field that, as it is, has already been too long in coming.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts School of Drama and senior strategy consultant at the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts.

May 19th, 2015 § § permalink

The story practically writes itself: fundraiser for anti-censorship group gets censored. Ironic headline, attention-grabbing tweet, you name it. That’s exactly what appears to have happened in the past few days as the Sheen Center for Thought and Culture’s decision to cancel a rental contract with the theatre group Planet Connections Theatre Festivity has been made public. Planet Connections was producing a one-night event, “Playwrights for a Cause,” on the subject of censorship, which would in part benefit the National Coalition Against Censorship.

The story practically writes itself: fundraiser for anti-censorship group gets censored. Ironic headline, attention-grabbing tweet, you name it. That’s exactly what appears to have happened in the past few days as the Sheen Center for Thought and Culture’s decision to cancel a rental contract with the theatre group Planet Connections Theatre Festivity has been made public. Planet Connections was producing a one-night event, “Playwrights for a Cause,” on the subject of censorship, which would in part benefit the National Coalition Against Censorship.

“Neil LaBute’s Anti-Censorship Play Is Censored, With Chilling ‘Charlie Hebdo’ Echoes,” was the headline of an article by Jeremy Gerard for Deadline. “Neil LaBute NYC Anti-Censorship Theater Event ‘Censored’ to Prevent Muslim Outrage,” topped a piece by Kipp Jones for Breitbart News. “Sheen Center Cancels Event Featuring Neil LaBute Play About ‘Mohammed’” was the title for Jennifer Scheussler’s story in The New York Times.

In the wake of the cancelation, the situation was described in a press release:

“Playwrights For A Cause,” an evening of plays by award-winning playwrights Erik Ehn, Halley Feiffer, Israel Horovitz and Neil LaBute, and a panel discussion concerning censorship in climate science and more inclusion of LGBT, women, and minorities in the arts, originally scheduled for June 14, 2015 at The Sheen Center at 18 Bleecker Street, has been canceled by the management of The Sheen Center.

Although their management originally approved the event and accepted full payment for the venue, a recent change in management resulted in the Center’s decision that some of the speeches the panel speakers were going to make, along with Neil LaBute’s play Mohammed Gets A Boner, are not acceptable or compatible with their mission statement. The diverse panel of speakers included Cecilia Copeland, speaking on the censorship of women in the arts; Kaela Mei-Shing Garvin, speaking on the censorship of environmentalists and climate scientists; Michael Hagins, speaking on the censorship & underrepresentation of minorities in the arts; and Mark Jason Williams, speaking on the censorship of LGBT artists.

On Tuesday, May 12, The Sheen Center canceled the entire event, including the Planet Connections opening night party which – ironically – was benefitting the National Coalition Against Censorship.

Upon my inquiry as to the cause of the cancelation, William Spencer Reilly, executive director of the Sheen Center, responded:

At the Sheen Center we are 100% for the right to free speech for every American, and always will be. However, when an artistic project maligns any faith group, that project clearly falls outside of our mission to highlight the good, the true, and the beautiful as they have been expressed throughout the ages.

We were disappointed to learn only a few days ago that one of the plays commissioned by Planet Connections Theater Festivity for the Playwrights For a Cause benefit event was called “Mohommad Gets a Boner” [sic]. We were totally unaware of this, and their Producing Artistic Director was fully cognizant that plays of this nature were unacceptable vis a vis our contract. (That contract, FYI, was with Planet Connections Theater Festivity, not with National Coalition Against Censorship.)

In light of this clear offense to Muslims, I decided to cancel the contract. Just as newspapers the world over have chosen not to publish cartoons offensive to Islam, I chose not to provide a forum for what could be incendiary material. At the Sheen Center, we cannot and will not be a forum that mocks or satirizes another faith group.

I am confident that the programming at the Sheen Center will continue to demonstrate our commitment to meaningful conversation about important issues, and will do so in a respectful manner — to people of all faiths, or of no particular faith.

Reilly wrote, in a separate e-mail, that he learned of the content of “Playwrights for a Cause” from a staff member on May 11, saying that his staff knew of three of the plays prior to his start as executive director in late January, that he signed the contract on February 10, and that his staff only learned of the La Bute play on May 8, when they “discovered” it on the Planet Connections website.

* * *

Before continuing, I should note my pre-existing relationship with NCAC. I have worked collaboratively with them on several instances of school theatre censorship, most notably on the cancelation of a production of Almost, Maine in Maiden NC and most recently on a threat to student written plays in Aurora, CO. Last year, they named me as one of their “Top 40 Free Speech Defenders.” They first informed me of the cancelation of “Playwrights for a Cause” because they were seeking suggestions of where they might relocate the event, and they did not solicit me at any time to write about the situation.

* * *

In the wake of the cancelation, the NCAC indicated to me that the contract for the event, signed by Planet Connections, provided for cancelations pertaining to content concerns. The statement from the Sheen Center (“unacceptable vis a vis our contract”) seemed to confirm that proviso. However, when I asked Glory Kadigan, producing artistic curator of Planet Connections about provisions for cancelation in the contract, she responded,

It does say no abortions on the premises. And it does say it can’t be pornographic. However the Sheen did not cite pornography as the reason they were breaking contract. They cited religion. I do not see anything in the contract that states ‘religious differences’ as a reason they are allowed to break contract. I also can’t find a clause that states that ‘not upholding their mission’ is a reason they can break contract.

Kadigan reaffirmed this in a subsequent e-mail:

When breaking contract with us – [a Sheen staffer] stated in an email that they had a right to break contract for “religious differences/being offensive to a religion” and not upholding their mission statement. The contract does not state this anywhere that we can find. This was just something she said in an email when breaking contract but it is not actually in the contract.”

Kadigan also said there was no provision in the contract for review or approval of content. In a follow-up e-mail, after two prior exchanges, I asked Reilly if he could share the specific contract language that provided for cancelation due to material that might prove offensive to any religious group. I received no response. He also did not respond to my inquiry asking if the decision to cancel the contract based solely on the La Bute play or if the content by the featured speakers part of the decision.

* * *

The website of the Sheen Center for Thought and Culture doesn’t make explicit that it’s a project of New York’s Catholic Archdiocese, although it does so in a current job listing for a managing director position on the New York Foundation for the Arts website. However, there are clear public indications that the new arts center has a Catholic underpinning, via its mission statement:

The website of the Sheen Center for Thought and Culture doesn’t make explicit that it’s a project of New York’s Catholic Archdiocese, although it does so in a current job listing for a managing director position on the New York Foundation for the Arts website. However, there are clear public indications that the new arts center has a Catholic underpinning, via its mission statement:

The Sheen Center is a forum to highlight the true, the good, and the beautiful as they have been expressed throughout the ages. Cognizant of our creation in the image and likeness of God, the Sheen Center aspires to present the heights and depths of human expression in thought and culture, featuring humankind as fully alive. At the Sheen Center, we proclaim that life is worth living, especially when we seek to deepen, explore, challenge, and stimulate ourselves, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, intellectually, artistically, and spiritually.

“Sheen Center for Thought and Culture” is also not the complete name of the venue, since its letterhead notes that it is in fact “The Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen Center for Thought and Culture.” I wouldn’t begin to suggest that the Center is hiding its affiliation with the church, but it is inconsistent in making the relationship clear.

I think it would benefit the Sheen Center enormously to clarify this, because a religious organization certainly has the right to determine what activities are appropriate in its own facilities. In making its facility available to outside groups for rent, rather than relying solely on its own productions, it behooves the Center to make clear how they might choose to assert their prerogative.

In an article last year in the Wall Street Journal, Elena K. Holy, who runs the New York International Fringe Festival, an early tenant of the Center, discussed her conversations with the Center’s leadership about content, prior to Reilly’s tenure:

The new spaces appealed to Ms. Holy, whose festival typically includes shows that would raise the eyebrows of conservative churchgoers. “We’ve had conversations about it,” said Ms. Holy. “They approached us. And my initial response was ‘Are you sure?'”

Ms. Holy said she was given no restriction on style or content, with one caveat: “They wanted to avoid anything that is hateful about a one group of people. And that probably wouldn’t be accepted to Fringe NYC anyway.”

Of course, the Fringe has the benefit of playing in more than a dozen venues, so presumably it can program its work at the Center accordingly, to avoid running afoul of its content restrictions. From this year’s crop of upcoming productions at the Fringe, I would say we’re unlikely to see Van Gogh Fuck Yourself, Virgin Sacrifice, The God Gaffe, or Popesical at the Sheen Center. I have no idea what they would make of An Inconvenient Poop or I Want To Kill Lena Dunham.

I do find myself wondering about another booking at The Sheen Center, specifically The Public Theater’s Emerging Writers Group Spotlight series. Since the beginning of April, and concluding next week, The Public has presented two free readings of each of ten new plays. While the titles don’t indicate any potential controversy as La Bute’s did – they include Optimism, The Black Friend, The Good Ones and Pretty Hunger – it’s hard not to wonder whether ten new plays by young writers by sheer coincidence manage to not make any statements that could be perceived as contrary or insulting to any faith. Since it doesn’t appear that the Sheen Center requires script material to be submitted in advance, is it possible that if a Sheen staff member attended a 3 pm reading in The Public’s series and heard statements they deemed to be contrary to the center’s mission, the 7 pm reading of the same script might be prevented from going on?

* * *

Reilly stated that the Center is “100% for the right to free speech for every American.” However, truly free speech means that we have to allow for both words and ideas that may not be acceptable to everyone. As a project of the Catholic Church, the Sheen Center certainly has the absolute right, as do all religious institutions in the US, to assert its prerogative over what is said and performed on its premises – but that is not 100% free speech for their tenants during their stay, even if the goal of restrictions is to foster, in Reilly’s words, “meaningful conversation that reaches for understanding and not polarization.”

While Reilly’s comments were not shared with her, Kadigan, in her final e-mail to me, seemed to directly confront the idea that the event was meant to polarize. She wrote:

‘Playwrights For A Cause’ is a great event in which we are building bridges. We had two Muslim actors performing that evening who were going to be on our panel. We also have African American artists performing and Asian American writers speaking. Women playwrights and LGBT playwrights were also going to be on the panel. Erik Ehn (one of the other presenting writers) is a devout Catholic. Israel Horovitz is Jewish. All of these people would be on the panel so we had a lot of different opinions/voices.

The events of the past week make it abundantly clear why the Sheen Center needs to be more transparent in its affiliation and restrictions. It should not enter into rental contracts which may be canceled for content concerns unless it makes explicitly clear what lines cannot be crossed in its facility – allowing arts organizations seeking to use the facility to consider whether they want their work subject to such scrutiny, or to work in a facility that imposes such content limitations on others. That way, all parties can be fully informed in their dealings at the very start, understanding that the Sheen Center, in the words of New York Times reporter David Gonzalez, “was envisioned as a vehicle for the church to evangelize through culture and art.”

As for “Playwrights for a Cause”? I’m told by the National Coalition Against Censorship that they and Planet Connections may have a line on a new venue. I hope they do (maybe even one I suggested), and that the result of this conflict will be to fill whatever theatre they end up performing in. After all, one of the results of silencing speech, even in those rare cases where the right exists to do so, usually has the effect of spreading the original message even further.

Update May 19, 2:45 pm: Planet Connections has announced that “Playwrights for a Cause” will take place as scheduled on June 14 at New York Theatre Workshop. However, the program will no longer include Neil LaBute’s piece. The playwright released a statement regarding his decision to withdraw the piece:

Unfortunately the event was starting to become all about my play and its title and not about the fine work that Erik Ehn, Halley Feiffer and Israel Horovitz were also presenting that evening, along with the accompanying speeches and the cause of the evening itself. “I had hoped my work would be viewed on its own merits rather than overshadow our message or become a beacon of controversy. I am honestly not interested in stirring hatred or merely being offensive; I wanted my play to provoke real thought and debate and I now feel like that opportunity has been lost and, therefore, it is best that I withdraw the play from “Playwrights For A Cause.”

Howard Sherman is the director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama.

May 4th, 2015 § § permalink

When it was all said and done, three student-written short plays, part of an evening of playlets, monologues and songs, went on as scheduled at Cherokee Trail High School in Aurora, Colorado. But in the 10 days leading up to that performance, the students claim they were told the plays and one student-written monologue were canceled. The students successfully garnered the attention of a local TV station, the National Coalition Against Censorship, and the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama over the impending cancelation.

However, the school claimed the shows were never canceled and that the students misunderstood, but first delayed the performance of the pieces in question and then rescinded that delay, which would have pushed the plays to a later date. The school cited lack of proper process for approval, issued permission slips to the parents of all participating students and sent a broader memo to parents regarding the content of the pieces, defining them as “suitable for mature audiences.” Amidst this, rumors suggested that some contemporaneous school vandalism was the work of the drama kids. One student-written monologue was canceled entirely because the student’s parents reportedly denied approval for it to be performed.

What precisely triggered all of this activity around brief student-written plays? LGBTQ subject matter.

* * * *

The cast and creators of “Evolution” at Cherokee Trail High School

Students in Cherokee Trail’s Theatre 3 class developed the “Evolution” evening under the banner of their student-run Raw Works Studio, working on them both in class and after school for more than a month. According Theatre 3/Raw Works students – including Josette Axne, Kenzie Boyd, Brandon McEachern, Dyllan Moran, and Ayla Sullivan, with whom I shared phone calls, texts and e-mails at various times beginning April 16 – they were informed by the school’s Activities Director Christine Jones on April 15 that because of the LGBTQ content in the student written works, the pieces could not be performed and would be excised from the pending performance set for April 24.

The students immediately took action, reaching out to the local media, setting up a Facebook page called “Not Original,” contacting the National Coalition Against Censorship (which in turn contacted the Arts Integrity Initiative), all over their understanding that the plays were being cut from the performance. After first speaking with Axne, I spoke and corresponded primarily with Sullivan in the first few days.

By the time Channel 9 in Denver, NCAC and Arts Integrity made contact with the school’s administration on April 16, Principal Kim Rauh had prepared a response, which portrayed the situation in a different light. It read, in part:

The student written plays will be performed at Cherokee Trail High School. The decision that was made was to postpone the date of the performance to allow our theater process to be completed. Students were invited to meet with us to work through the process and give the necessary time to work through all of the “what ifs” and attempt to be proactive as opposed to reactive and to plan for success. With every production there is an element of both directorial and administrative review and approval. The plays were submitted after the due date for final approval for the original performance date. We have extended the process timeline to allow the plays to be performed at a later date at Cherokee Trail High School.

Channel 9’s account of the situation, the only significant local news story, was reported on the evening news on April 16, stating that the pieces would now be performed on May 9.

* * * *

“Not Original”’s Facebook post about school vandalism

On Friday morning April 17, shortly before 8 am Colorado time, I received, in the space of ten minutes, an e-mail and phone call from Ayla Sullivan. She was deeply concerned that an act of vandalism at the school overnight was being attributed to the Theatre 3 students, even though she said it had been covered up before students arrived at the school that morning, so that not only were she and her classmates not involved, they didn’t even know the nature of the vandalism. Sullivan asked how the drama students should address this, and I advised them to tell the truth and make clear their position about whatever had occurred. Ten minutes later, the following message was posted, as a screenshot from a cellphone, to the “Not Original” Facebook page:

The vandalism we are now aware of that happened earlier this morning was not done by any member of Raw Works Studio and is not affiliated with the Not Original Movement whatsoever. Due to none of the members even seeing this vandalism, we do not know what it says and if it is even related to us. Whatever the markings say, we can not see it because it was covered as early as 6:45 this morning.

If someone wrote something that is related to Not Original through vandalizing public property, we absolutely oppose it. We do not support vandalism, violence, or hate speech. We do not support this action. We are, and have always been, a peaceful movement.

This is not the way towards change. This is not acceptable.

To date, the students say they haven’t heard anything more about the vandalism. It was a brief source of anxiety, but not central to the dispute.

* * * *

On April 17, I sent a series of questions about the events of the past two days to Principal Rauh, copying Tustin Amole, the director of communications for the school district. It was Amole who responded, very promptly. Describing the reasons and process for what was happening with the plays, she explained:

All student performances are subject to administrative review prior to rehearsals beginning. The teacher is responsible for submitting material for consideration. I do not know how soon prior to that the students finished the plays. Regardless of when the materials are submitted, there is a long-standing process which must be followed.

In cases where the material may be mature or sensitive, the school meets with the parents of the students involved to make sure that they have permission to participate. We would then inform the broader community so that they are aware of the subject matter and can make a decision about whether they want to come and perhaps bring younger children.

Because I had pointed out that the new date set for the student written works (all of the other pieces were to be performed as originally scheduled) conflicted with tests for Advanced Placement and the International Baccalaureate, Amole wrote me:

In our effort to ensure that the students have the opportunity to perform the plays, we selected a date that allowed time for the process. We understand concerns about the timing, but this is the only available opportunity before school ends.

Following this exchange, I wrote again to Amole, inquiring as to the school’s specific concerns about the material, which had gone unmentioned. She replied:

The plays concern some issues around sexuality and gender identity. We would not censor the subject matter, but do work to ensure that all parents were informed and give consent for participation, and that attendees know the nature of the material. In other words you would not take children to a movie without knowing what it is about, nor are you likely to allow children to participate in an unknown activity. In the Cherry Creek School District, parents are given the option of reviewing activities, books and other materials and asking for alternatives if they object to what is assigned.

As for when the review process had begun, she responded:

The conversations with the students began when the material was submitted to administrators for review. We were looking for alternative dates to complete the review process when some of the students decided to call the media. Because they did not have that class yesterday, they were unaware that a new date had been determined. Had they waited to talk to their teacher during the next class, they would have been informed. They also always have the option of coming to the principal to express their concerns and they chose to call the news media instead. We regret that they chose not to work through our long established process.

That same day, the students told me, there were two meetings with Christine Jones, who outlined for them the plans for going forward.

* * * *

After all of this, imagine my surprise when, just before 5 pm Colorado time on Monday, April 20, the NCAC and Arts Integrity Initiative received the following e-mail from Ayla Sullivan:

We have officially gotten our show back! Thank you so much for your help and support. Your belief in us is the only reason we have this. Thank you.

I wrote Rauh and Amole minutes later, to find out how the timetable had been restored to the original date. Amole replied two days later, sharing the communication that was going out to parents that day, which read in part:

I wanted to take this opportunity to communicate an update regarding the Theatre 3 production at Cherokee Trail High School, Evolution. Evolution contains a series of vignettes including songs, original student works and published scenes centered around the theme of love, some of which contain topics that may be considered best suited for mature audiences.

Because we are not putting topics on the stage, but rather actual students with actual feelings it was our desire to ensure that we had the time to adequately communicate the nature of the production with our parents and community members to help ensure the safety and well-being of all involved. The events of the past week have allowed us to do so and as such the administration, director and students have determined that we can perform the show on the originally scheduled date of April 24.

In response specifically to me, Amole added:

As of now, we do not have permission from all of the students’ parents to participate. While we continue to work to obtain the required permissions, we will honor the parent’s wishes, as per district policy. The performances of those students who do have parent permission will go forward.

* * * *

Graphic design for “Evolution” at Cherokee Trail High School

On April 24, the following student written pieces were performed as part of “Evolution”: A Tale of Three Kisses by Kenzie Boyd and Brandon McEachern , Roots by Dyllan Moran, and Family: The Art of Residence by Ayla Sullivan and Brandon McEachern. The evening was, in the words of Dylan Moran, in an interview with KGNU Radio that he gave the day of the performance, about “how love evolves, both through time and within ourselves.”

On April 29, five days after the performance, I spoke with the students to ascertain how the performance had gone. They reported attendance in the neighborhood of 300 people, which while it only filled the orchestra section of their theatre, they said was comparable with other performances of this kind, and they seemed satisfied with the turnout. But had there been, when it was all said and done, any censorship of the work?

Brandon McEachern replied, “The only thing that was asked to be changed was certain curse words. There was no content change. It was just not having the word ‘shit’ or something like that. Those are the only changes they asked for the shows.”

“Certain words were allowed to fly in certain shows that weren’t allowed in others,” Moran continued. “It was very touch and go. There wasn’t any set rule. We’d be performing and it was like, ‘That one’s not OK,’ and we’d move on. Life Under Water did have changes, not as extensively as the original ones, probably because it had already been produced.”

I wondered, given the representations of Amole on behalf of the school district, whether the students had in fact misunderstood their conversation with Jones on April 15, given all that had transpired since. The unanimous reply of Boyd, McEachern, Moran, and Sullivan was that they hadn’t.

“It was very clear to us, on the day, that the show would not be happening,” said Moran. “There was no editing, there was no pushing it to a later date, there was no discussion about it. It was only when we got involved with the media that they changed their story and said, ‘No, we are going to push it back. We told them we were going to push it back, they just didn’t listen to us’.”

Sullivan continued, “There was also the sense of, when we were approached later, that Friday, which was April 17, by our activities director, that we were being guilt tripped, that we didn’t give her the benefit of the doubt and we immediately met with the media outlets and tried to make this a bigger thing than what it was – that it was our fault for misunderstanding, which never happened. It was very clear.”

When asked if it was made clear to them why there was concern over the material, Sullivan said there was a single reason given, that it was about “how the community would react to LGBT representation.” The students said it was on Friday that they were told by Jones that if they could meet all the necessary requirements by Monday, in terms of parental permission, the school leadership would reconsider the May 9 plan.

Had the students anticipated any pushback against the student written shows? “When we were going through the entire process,” McEachern said, “I didn’t think the school would tell us that these were controversial issues and it would make people uncomfortable. I just thought it would go on like a regular show. I didn’t think there would be any backlash.” Sullivan added that once the news broke, “there was nothing but support.”

Referring to sentiment within the school, Boyd said, “I think immediately, as soon as we found out, that there was an immediate buzz on Twitter, everyone from school and even from out of state, that were talking about this and how disappointed they were in the school. I think it was definitely at first – the whole situation is definitely a lesson for schools in general and even for society in general, to really look at people and look at what they’re saying versus what they’re doing. Because everybody’s always talking about equality, equality, equality but then when they actually get the opportunity, it gets shut down pretty fast. So I think it’s a big lesson, but I also think that in a positive manner other than just lessons, it really brought everyone together, because I’ve never seen this school so united.”

* * * *

But what of the student-written monologue, Ever Since I Was A Kid? The students I spoke with, who explained that it had been cut because the parents of the student author had declined to give permission, spoke freely of the piece. They shared that it was a personal account of a teen who was in the process of gender transition. It suggests that this piece was, at least in part, what Amole referred to on April 22 when she wrote me that not all permission slips had been received.

I must note that I spoke to the author/performer of “Ever Since I Was A Kid” on April 20, before it was clear that parental permission was being withheld and that the piece in question would not be performed. Because the situation had changed and I was not able to speak with this student again, I have withheld the content of our interview because, despite sending messages through the other students, I could not confirm whether the author was still comfortable with my using our conversation. The students I spoke with said their classmate was permitted to perform in other parts of “Evolution,” just not with the original monologue.

* * * *

As much as I have tried to reconstruct the timeline of this incident, it is clear that the students’ account and that of the administration differ. The students say they were told originally, in no uncertain terms, that the student-written pieces were being cut. The school maintains that they simply needed time to put the work in context.

Missing from this report is any account of the circumstances from either the Theatre 3 teacher, Cindy Poinsett, or the Activities Director, Christine Jones. Because it is typical in most schools that faculty and staff do not speak to the press without approval, and because after the first response to my inquiry to the principal, all responses came from the school system’s spokesperson, I did not attempt to contact either Poinsett or Jones. Should either of them choose to contact me directly, I will amend this post to reflect their input.

I have to say that throughout this period, the students I spoke with were remarkably poised in their accounts of what took place. While as I noted, the school was very responsive to my inquiries, there is one notable shift in the timeline they created: on April 16 they said it would take three weeks to put everything in place in order to allow the student written pieces to be performed. Two business days later, everything had been accomplished that allowed the pieces to go forward as originally scheduled.

That the original “solution” would have excised these pieces from the April 24 performance and isolated them as their own event, that May 9 was initially the “only” possible date on which they could do so, suggests that the administration was responding on the fly, in response to external inquiries. If the students had misunderstood what they were originally told, why on April 15 didn’t the school simply say that all would go on as planned if the students brought in signed permission slips by April 20, as they ultimately did, instead of promulgating a new date?

I also have to wonder why, as has so often been the case when potential incidents of censorship arise in high schools, was the initial reason given for the action the assertion that an approval process had not been followed? The students say they had been working on the pieces for more than a month and were never given any deadline or reminded to get their materials in by a certain date. Is Principal Rauh suggesting that the students and their teacher had been keeping the work under wraps? Was there a disconnect between the teacher and the activities director, or between the activities director and the administration?

At the root of this incident remains the skittishness that schools have regarding any public representation of LGBTQ issues and lives to their community at large. While opinion polls show that six out of every ten Americans support marriage equality, that percentage jumps to 78 percent for people under 30. Presumably that is at least the same for the general acceptance of LGBTQ Americans overall, although to quote a New York Times editorial, “being transgender today remains unreasonably and unnecessarily hard.”

So it seems that whatever precisely took place at Cherokee Trail, it derives from the students having a more evolved attitude towards equality than the school fears the local adult community may hold. How long will students be required to get permission before they can tell true stories of their own lives and the lives of those around them? When will all schools stand up for student expression of their lives and concerns on the stage from the outset, and stand firm against those who continue to oppose the tidal wave of equality that will inevitably overtake them?

* * * *

I asked several of the students what the ultimate takeaway was from their experience.

Sullivan said, “We got a lot of positive support and had a positive show, but my biggest concern is that now that our department has made a name for itself for doing original content, the administration is going to create a harder process, a new deadline. I’m concerned that student-written work will not be able to be performed the way it should, that now they will have something of a deadline process to fall back on and use that to censor other voices and censor experiences in that light. That kind of worries me, because we’ve already seen an attitude of they don’t want this to continue and they don’t want to have to deal with this again.

“I definitely feel that our principal and our activities director have found that this has created such a mess that they don’t want student-written work to continue, that they don’t want Raw Works, the studio itself, to be representative of the theatre department anymore and that they don’t want student-directed student works.”

Boyd picked up that thread, saying, “I don’t think it’s as much concern about it continuing, as much as they’re going to make it so hard to continue that we’re going to have to stop ourselves. I definitely think there’s been so much backlash on them now that they can’t just say no more original work, but I do think that the process next year is going to be a lot harder to the point that it may be impossible to put on original works.”

When I pressed the students on whether anything explicit had been said about the future for student written work, McEachern said, “Right now, it’s just a concern of ours. They have not said anything.”

In my last communication with Tustin Amole, I asked whether the events surrounding “Evolution” would have any impact on the Theatre 3 class, Raw Works or student written plays in the future, and received the following reply:

Our process will remain unchanged. As I have already explained, it is the standard process that has worked well for us for a long time.

The class also will be unchanged. Students will be able to write and perform their own work.

So for now, all we can do is watch and wait until next year, to see what stories get told at Cherokee Trail.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School for Drama.

March 30th, 2015 § § permalink

If you have any interest in the subject of diversity in entertainment, no doubt you’re aware of the firestorm kicked off last week by TV editor and co-editor-in-chief of the entertainment website Deadline, Nellie Andreeva. An article/op-ed under the headline “Pilots 2015: The Year of Ethnic Castings – About Time Or Too Much Of A Good Thing” was taken by many (myself included) as an insensitive response to a greater commitment by TV networks to casting new shows with actors representing a wide swath of racial diversity.

If you have any interest in the subject of diversity in entertainment, no doubt you’re aware of the firestorm kicked off last week by TV editor and co-editor-in-chief of the entertainment website Deadline, Nellie Andreeva. An article/op-ed under the headline “Pilots 2015: The Year of Ethnic Castings – About Time Or Too Much Of A Good Thing” was taken by many (myself included) as an insensitive response to a greater commitment by TV networks to casting new shows with actors representing a wide swath of racial diversity.

What you may have missed was Deadline’s apology for the article, and most specifically the headline, which was altered the next day in response to the criticism leveled at the site. In his weekly colloquy with his former Variety colleague Peter Bart on the site, Andreeva’s co-editor-in-chief Mike Fleming Jr. stated the following:

“I wanted to say a few things to our core readers who felt betrayed. That original headline does not reflect the collective sensibility here at Deadline. The only appropriate way to view racial diversity in casting is to see it as a wonderful thing, and to hope that Hollywood continues to make room for people of color. The missteps were dealt with internally; we will do our best to make sure that kind of insensitivity doesn’t surface again here. As co-editors in chief, Nellie and I apologize deeply and sincerely to those who’ve been hurt by this. There is no excuse. It is important to us that Deadline readers know we understand why you felt betrayed, and that our hearts are heavy with regret. We will move forward determined to do better.”

That’s a clear statement, and admirable, but I have lingering questions, about both the form and the content of the apology itself.

1. If Andreeva and Fleming recognized the problems quickly, why did they wait five days before apologizing, and only then via comments in a piece headlined, “Bart & Fleming: A Mea Culpa; Frank Sinatra Re-Cast; Tent Pole Assembly Line”? If they feel so strongly, why wasn’t this a standalone statement signed by both editors-in-chief, clearly marked as such, rather than included in a tete-a-tete that discussed other, irrelevant matters?

2. If Andreeva apologizes for the handling of the subject, why hasn’t she linked to the Bart & Fleming piece with the apology from her Twitter feed (for a start), where a link to the original piece, under its original headline remains if you scroll back a few days? Why hasn’t she taken any ownership of “her” apology? By not doing so, it’s easy to wonder about the sincerity, and even the source, of the apology.

3. Fleming responds to a question from Bart about why the piece wasn’t taken down, saying:

“It was 12 hours before I awoke to numerous e-mails, some by people of color who are sources, who trust us, who were rightfully incensed. At that point, the damage was done. I don’t believe you can make an unwise story disappear and pretend it didn’t happen.”

However, while Fleming acknowledges the change of headline, he fails to comment on internal edits to the piece, which included moving the third and fourth paragraphs much deeper in the article, perhaps putting them in better context. I also noted the addition of a phrase about “a young Latina juggling her dreams and her heritage” which I hadn’t spotted in the original. Why aren’t those changes made clear in the note on the bottom of the original piece? It seems an effort to say that all that was wrong was the original headline.

4. While it’s commendable of Fleming to not pretend that the original article never happened, I’m surprised that if you read the piece online now, there’s no evident link to the apology. To leave the article standing without that context, given how it is supposedly perceived internally at the site per Fleming’s own account, once again suggests that the apology is something less than thorough.

I have no doubt that people will be scrutinizing Deadline’s coverage of diversity, especially when Andreeva writes about it, for some time to come. Giving Fleming the benefit of the doubt as to his intentions, he needs to take a few more steps to demonstrate the depth of his commitment – and Andreeva needs to stand up and take responsibility for what she wrote and acknowledge the flaws. Otherwise, she’s left her partner to clean up her mess, and we’re all still wondering where her heart really lies.

Howard Sherman is senior strategy director at the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama.

March 23rd, 2015 § § permalink

If you happen to know of any young people who you’re trying to dissuade from careers in the creative arts, you might want to casually leave around two new books for them to find. Scott Timberg’s Culture Crash: The Killing Of The Creative Class (Yale University Press, $26) and Michael M. Kaiser’s Curtains?: The Future Of The Arts In America (Brandeis University Press, $26.95) both paint dark pictures of the state of the creative arts and where they’re headed, enough to send one right into investment banking if it remains a choice.

Timberg, a former arts journalist at the Los Angeles Times who writes the “Culture Crash” blog for ArtsJournal, predominantly focuses on the music industry and the state of legacy media and journalism, with nods to architecture and literature, while Kaiser, former head of the Kennedy Center and now leader of the DeVos Institute of Arts Management, concentrates on the world of symphonies, opera and dance. As an avid consumer of music and journalism, my interests run closer to those explored by Timberg; professionally my background comes closer to the disciplines discussed by Kaiser, but (troublingly) neither book spends much time at all on theatre, my actual profession and leisure time avocation as well.

Timberg, a former arts journalist at the Los Angeles Times who writes the “Culture Crash” blog for ArtsJournal, predominantly focuses on the music industry and the state of legacy media and journalism, with nods to architecture and literature, while Kaiser, former head of the Kennedy Center and now leader of the DeVos Institute of Arts Management, concentrates on the world of symphonies, opera and dance. As an avid consumer of music and journalism, my interests run closer to those explored by Timberg; professionally my background comes closer to the disciplines discussed by Kaiser, but (troublingly) neither book spends much time at all on theatre, my actual profession and leisure time avocation as well.

As a result, neither book reveals a great deal to me that I’ve not read about before, or experienced personally in some cases. But while both are published by academic presses (perhaps its own comment on broad-based interest, or lack thereof, in arts and culture), neither seems targeted at industry insiders. Instead, they are surveys of where we are now and how we got here, with a limited amount of prescriptive suggestions for how the tide that favors mass entertainment over the rarified or personal might be turned or at least survived in new forms. Both place a great deal of blame on technology for the woes they recount.

Of the two, I was more drawn to Timberg’s book, which, no doubt due to the author’s experience as a professional writer, is the more elegant, immersive read, peppered throughout with specific stories that support his thesis of cultural decline, a vision notably counterpointed with Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class (with a book cover designed to evoke that oft cited book). Timberg particularly worries about the loss of a wide range of social influencers who could guide existing and potential audiences to works that might interest them, from knowledgeable record store clerks to professional (paid) reporters and critics. While it’s a valid point, Timberg falls prey to making it seem, at times, as if he’s bemoaning his own employment status and that of his many colleagues who have been decimated by the contraction in print journalism, never more so than when he cites the decline in the popular portrayal of critics as having slid from George Sanders as Addison DeWitt in All About Eve in the 1950s to Jon Lovitz as Jay Sherman in the cartoon The Critic in the 1990s. That said, he does make strong points about the fracturing of a common culture even as a blockbuster mentality has overridden many creative industries, a seemingly oxymoronic concept. He also cites a wide array of sources, both from other writing and newly conducted interviews, and his fields of interest are admirably broad.

Kaiser’s book resembles a series of lectures about the state of the performing arts – a look at a golden era in the latter half of the 20th century, where we are now, where we may be in 20 years time, and how we might make things better. Unfortunately, the lectures seem to spring wholly from Kaiser himself, as he quotes no experts, provides no data, and doesn’t include either an appendix or bibliography. It seems we are to take what Kaiser tells us simply on faith, even such sweeping statements as “While the outlook for the performing arts is dire, museums have better chances for survival” or “Theatre organizations should fare better than symphony orchestras.” In the case of the latter statement, much as I would dearly love it to be true, it flies in the face of recent studies from the National Endowment for the Arts, cited by Timberg but AWOL from Kaiser’s survey. Given how much of his brief book is taken up with prognostication, its unfortunate that Kaiser doesn’t extrapolate from existing data; in imagining 2035, it’s surprising that ongoing demographic shifts, especially in regards to race and ethnicity, in the country play so little role in his thinking. That’s not to say he doesn’t have some interesting observations, among them the thesis that while the end of Metropolitan Opera touring gave rise to more regional opera companies in the 80s, the success of the Met Live cinecasts may now be undermining those very troupes.

Kaiser’s book resembles a series of lectures about the state of the performing arts – a look at a golden era in the latter half of the 20th century, where we are now, where we may be in 20 years time, and how we might make things better. Unfortunately, the lectures seem to spring wholly from Kaiser himself, as he quotes no experts, provides no data, and doesn’t include either an appendix or bibliography. It seems we are to take what Kaiser tells us simply on faith, even such sweeping statements as “While the outlook for the performing arts is dire, museums have better chances for survival” or “Theatre organizations should fare better than symphony orchestras.” In the case of the latter statement, much as I would dearly love it to be true, it flies in the face of recent studies from the National Endowment for the Arts, cited by Timberg but AWOL from Kaiser’s survey. Given how much of his brief book is taken up with prognostication, its unfortunate that Kaiser doesn’t extrapolate from existing data; in imagining 2035, it’s surprising that ongoing demographic shifts, especially in regards to race and ethnicity, in the country play so little role in his thinking. That’s not to say he doesn’t have some interesting observations, among them the thesis that while the end of Metropolitan Opera touring gave rise to more regional opera companies in the 80s, the success of the Met Live cinecasts may now be undermining those very troupes.

Reading the two books back to back, I was struck by the fact that both hit some similar themes (the loss of shared cultural language and experience, the impact of electronic media) yet diverge in their exemplars. While Kaiser’s book also doesn’t include an index, I did a fast pass through to see whether certain areas came up frequently, and found 14 references to The Kennedy Center and eight to the Alvin Ailey Dance Company (both of which Kaiser led) and a whopping 19 mentions of the Metropolitan Opera – all organizations which appear nowhere in Timberg’s index, which lists its greatest citations for areas of discipline rather than particular purveyors (the film industry, the economy, the indie music scene to name three). Both books may focus on the state of culture and its future, but their respective attentions are essentially balkanized.

If I were teaching a survey course in arts leadership, I might well assign both books early in the semester, albeit with a restorative break between them to replenish some sense of optimism. But both are merely starting points for a conversation, each in their own way raising areas of concern, yet stinting on any semblance of how those concerns can be addressed, battled or even embraced. To be fair, Timberg is a reporter, recording and interpreting, but Kaiser is training arts leaders, so its more incumbent upon him to offer something prescriptive. We can bemoan the fact that Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts are a thing of the past, or long for the one on one counsel of record and bookstore employees, but that’s not likely to bring them back. If our cultural appreciation and literacy has fallen, can it get back up – and if so how? That’s the book I need to read. Soon.

March 12th, 2015 § § permalink

Vandalized “Women of Purpose” (photo courtesy of Kate Czaplinski, Trumbull Times)

Last night, a painting hanging in the town library in Trumbull, Connecticut was defaced, while in the same building, the library board was holding a meeting about the display of said painting. I wish I could say I was surprised that this happened, but to be honest, I’m not. I’ve been expecting it. I believe this was the inevitable result of a series of events that broke into public awareness two weeks ago, when the town’s First Selectman ordered the painting removed.

Let’s review the timeline:

- A collection of paintings entitled “The Great Minds Collection,” commissioned by Trumbull residents Richard and Joan Resnick has been on display at the Trumbull Library since the fall of 2014. It had previously been on display at nearby Fairfield University.

- In mid-February, the Bridgeport Archdiocese made it known publicly that they were displeased about one painting in the collection, “Women of Purpose,” because it included in its depiction of influential women both Mother Teresa and Margaret Sanger. The library itself received eight calls of complaint and a religious order in India notified the town that any use of Mother Teresa’s image was a copyright violation.

- In response to the copyright claim, which experts – save for the town attorney – agreed was specious, the First Selectman Timothy M. Herbst ordered the librarian to remove the painting to protect the town. He said he required an indemnification from the Resnicks against any copyright claims that might arise from the painting, which the Resnicks had already provided verbally and were happy to commemorate in writing. This action generated significant press attention throughout the state.

- When the First Selectman then said he required indemnification against any claims that might arise from possible damage to the collection while in the town’s care, publicly chastised the librarian and library board for not having secured one previously, and accused the librarian of ethics violations in her dealings with the Resnicks.

- The Resnicks agreed to sign an indemnification agreement against damage to the collection, but balked when the town reportedly proffered language that could have made them responsible for such instances as one of the paintings falling off the wall and causing damage or injury, as well as requiring that the Resnicks foot the bill for repairing and repainting library walls when the exhibition concluded.

- On Friday, March 6, the town added a rider to its own insurance policy covering the paintings and “Women of Purpose” was rehung at the library.

- Five days later, someone defaced the image of Margaret Sanger.

As quoted in the Trumbull Times, First Selectman Herbst responded to last night’s vandalism by saying, “I think this proves exactly what we have been saying for the last three weeks.”

Here’s what’s faulty with Herbst’s argument: this wasn’t a public issue until he made it one. By demanding the removal of the painting, by sending a barrage of communications to the Resnicks and others and by simultaneously releasing them to the local press, he elevated dispute into controversy, all the while saying he was doing it to protect the town. His tactics likely led to the painting becoming a target, in a way it hadn’t been before.

Why didn’t Mr. Herbst simply ask the Resnicks for indemnification, working through the established channels of their relationship with the library? Why, if the town had such language ready for works that might be displayed in town hall, wasn’t that immediately offered to the Resnicks? Why did Herbst accept the sole legal opinion that encouraged removal of the painting, instead of seeking further guidance from an intellectual property lawyer? Why if the concern was for the safety of the paintings while in the possession of the town did he demand only that the single painting, the one which had been the subject of complaints, be removed, when surely his liability concerns pertained to all of them?

While I don’t deny that some of the responses from the Resnicks and their attorney were part of the escalation of tensions, the fact is this could have all been handled quickly and quietly as part of an administrative process. Instead, by selectively removing the one painting that had received some complaints – an act of censorship, not protection – this was transformed into a culture war: of art, of ideas, of expression and of religion.

In all of the discussion of the painting itself – and I respect the beliefs and opinions of all of those who are distressed by it – I haven’t seen anyone make the argument about the fact that in this work, Mother Teresa and Margaret Sanger are at the opposite ends of the frame. I’m not art critic, but one could validly say that while all contained are influential women, the great nun and the family planning pioneer are literally as far apart as they can get, opposite ends of the spectrum. Might that not reflect their divergent views? It’s one simplistic interpretation, I know, but might it not be a valid one? Does their mere presence in the same image declare that one endorses the tenets of another?

I am impressed that Dr. Resnick has stated that he will not press charges if the vandal is caught, which is a generous statement that shows his desire to return the conversation to one of ideas, not vindictiveness. That said, Mr. Herbst must be held to his statement to the Connecticut Post that, “”We’re going to nail the person who did this and Police Chief (Michael) Lombardo and I are mutually committed to holding the person who did this accountable.” Without that investigation, without someone held responsible, the town sends the message that vandalism is an acceptable form of debate anywhere in the town of Trumbull, let alone inside a town property.

It’s unfortunate and infuriating that we’re seeing the many faces of censorship in Trumbull. It’s also unfortunate that the actions of town officials set it in motion on the pretext of municipal protection, rather than handling what was obviously a potentially charged situation with finesse and with care for the protection of open public discourse and the expression of ideas through art.

Howard Sherman is Director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama.

Note: crude or ad hominem attacks in comments will be removed at my discretion. This is not censorship, but my right as the author of this blog to insure that conversation remains civil. Comments will not be removed simply because we disagree.

March 4th, 2015 § § permalink

Remember Trumbull, Connecticut?

That’s the town where a new high school principal canceled a production of the student edition of the musical Rent in the fall of 2013. The resultant outcry from students, parents, town residents, the media and interested third parties (including me) was such that three weeks later, the show was reinstated. It was produced at the high school in 2014 without any incident.

After my advocacy for Rent, I hate returning to the subject of the arts in Trumbull, for fear of being accused of piling on. That said, there must be something in the water supply in Trumbull, because it’s right back at the center of an arts censorship controversy again. Timothy M. Herbst, the town’s first selectman, has ordered the Trumbull Library to remove a painting by Robin Morris from a current exhibition, “The Great Minds Collection,” commissioned and loaned by Trumbull residents Richard and Jane Resnick. The painting in question, “Women of Purpose,” features representations of a number of famous women, including Mother Teresa, Betty Freidan, Gloria Steinem, Clara Barton and Margaret Sanger.

After my advocacy for Rent, I hate returning to the subject of the arts in Trumbull, for fear of being accused of piling on. That said, there must be something in the water supply in Trumbull, because it’s right back at the center of an arts censorship controversy again. Timothy M. Herbst, the town’s first selectman, has ordered the Trumbull Library to remove a painting by Robin Morris from a current exhibition, “The Great Minds Collection,” commissioned and loaned by Trumbull residents Richard and Jane Resnick. The painting in question, “Women of Purpose,” features representations of a number of famous women, including Mother Teresa, Betty Freidan, Gloria Steinem, Clara Barton and Margaret Sanger.