June 12th, 2013 § § permalink

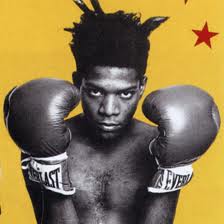

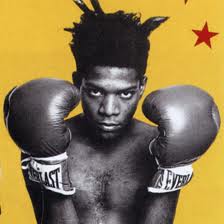

Jean-Michel Basquiat

For those complacent about the ongoing reduction and elimination of professional arts journalism, I would like to offer a small but concrete example of where this decline is leading us.

On Monday June 10, the website BroadwayWorld.com published the following item, credited only to “BWW News Desk.” In my experience, this usually means that it is, more or less, taken directly from a press release.

Eric LaJuan Summers and Felicia Finley to Star in BASQUIAT THE MUSICAL Reading, 6/24

Basquiat, a new musical based on the life and times of 80’s art-star, Jean-Michel Basquiat will get a private reading on Monday June 24th.

Basquiat was a New York graffiti artist who shot to stardom in the early 80’s with his neo-expressionistic paintings and bad-boy image. He was a part of a cultural revolution that included fellow painters, Keith Haring and Fab 5 Freddy, New Wave bands Blondie and Talking Heads and Basquiat’s mentor, Andy Warhol. He was one of the most sought after painters in the 80’s until his untimely death in 1988 at only 27 years old. Written by Chris Blisset (music and lyrics), Matt Uremovich (lyrics) and Larry Tobias (book), Basquiat deals with the triumphs and failures of one of the art world’s most controversial figures.

The cast stars Eric Lajuan Summers (Motown) and Felicia Finley (Mamma Mia). Summers, who recently won an Astaire Award for Outstanding Male Dancer for Motown the Musical, will be reading the title role of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Other performers include: Roger DeWitt, Chad Carstarphen (In the Heights), James Lambert, Justis Bolding (Woman in White) Frank Viveros, Jason Veasey (Lion King), Gabriel Mudd, Rubin Ortiz, and Eddie Varley.

Basquiat is conceived and directed by Paul Stancato.

Now this is a pretty straightforward announcement of something that happens constantly in New York, a reading of a new musical. But in our era of search engine optimization, curation, consolidation, aggregation and “reporting” based solely on something written elsewhere, stories begin to grow. On Tuesday June 11, The Huffington Post carried the following “story,” with no byline, which escalates some of the language around this one-day industry reading. It is, presumably, drawn from the same source as the Broadway World item, or extrapolated from the item itself.

‘Basquiat The Musical’ Is Reportedly Happening

Move over Matilda, there is a new unlikely Broadway star in town. According to Broadway World, “Basquiat The Musical” will get a private reading on June 24 with stars Eric LaJuan Summers and Felicia Finley.

That’s right, art star Jean-Michel Basquiat will have his meteoric life immortalized in song, thanks to writers Chris Blisset, Matt Uremovich and Larry Tobias, and director Paul Stancato (who is married to Felicia Finley).

Of course if any artist were to get a Broadway debut, we would assume it would be Jean-Michel. The neo-Expressionist bad boy’s iconic style, charismatic persona and tragic early death make for an extremely compelling story. He’s already been the subject of documentary and film, and a blockbuster auction at Christie’s, but the musical threshold has yet to be crossed…until now.

Summers, who previously starred in “Motown,” seems like a good fit to play the graffiti king, leaving us wondering who will play Basquiat’s mentor Andy Warhol and brief beau, Madonna.

What do you think of the prospect of a Basquiat-based musical? And which artist would you most like to see doing jazz hands on Broadway? Fingers crossed for Gerhard Richter…

On the very same day that a one-day reading is announced by Broadway World, The Huffington Post informs us that Basquiat is “reportedly happening” as a Broadway show and the actor taking the lead role in the reading has been elevated to having “previously starred in Motown.” Considering that Motown has only been running for a couple of months, the use of past tense seems unwarranted, and the actor in question is a member of the ensemble there, not playing a lead role (the Motown ensemble plays a wide variety of small roles). In addition, this as-yet unseen reading is apparently already generating buzz, as the unnamed reporter opines that this actor “seems like a good fit to play the graffiti king,” even though the reporter is unlikely to have read the script, heard the score or been able to extrapolate from the actor’s Motown performance how his talents would bear on that material. Incidentally, as I write, 133 people saw fit to share this story with others, 67 tweeted it out and 463 “liked” it.

Then, in turn, this morning, Complex.com does its own “reporting,” credited to Justin Ray (noting it is “via The Huffington Post,” but also citing Broadway World as a source) in which Basquiat is now a sure thing.

“Basquiat The Musical” Will Be Coming to Broadway

We have heard a slew of rappers refer to Jean-Michel Basquiat in song, however the influential artist’s involvement with music will be taken to the next level. Basquiat The Musical will be having a private reading on June 24 according to Broadway World.

Yes, the prolific art icon will now have a musical dedicated to his life starring Eric LaJuan Summers and Felicia Finley. The musical was written by Chris Blisset, Matt Uremovich, and Larry Tobias. It will be directed by director Paul Stancato. Although it is unexpected, we imagine it will be a pretty awesome story. It’s another thing he could have added to his hilarious resume.

Eric LaJuan Summers starred in the big musical Motown and is sure to play the part well. However details have not been released as to who will play Madonna or Andy Warhol. However we anticipate it will become popular, though it will be hard to outsell his works (which have gotten crazy amounts of dollars).

Yes, in less than 48 hours, Basquiat is not only “coming to Broadway” – all reference to a reading is gone in the headline – but Complex “anticipate[s] it will become popular” and the lead actor is “sure to play the part well.” The snowball effect is well underway, for a show that hasn’t even had its industry reading.

I don’t bring this up in order to cast any aspersions on the artists or creators of Basquiat; I genuinely wish them well. But these three items, taken together, demonstrate how quickly some simple facts about a show early in its development blow it up into a Broadway show based solely on the voracious appetite of news consolidators and headline fabricators. Have they done so wholly of their own accord, or were they easy prey for a wily publicist? Hard to say.

Since I was a child, I’ve known the phrase, “You can’t believe everything you read.” But nowadays, when it comes to news, when facts are elaborated upon and disseminated by multiple “news” sources, our skepticism needs to be greater than ever before. If this is the new standard for news, we shouldn’t be bemoaning the death of accuracy, even more than the anticipated death of print?

And as for arts coverage? Without reliable and verifiable reporting, whether in print or online, our descent into nothing but gossip draws ever closer.

* * *

Full disclosure: I periodically cross-post blog entries from this site to The Huffington Post as an arts blogger, for which I receive no compensation, and I have not communicated with anyone there in connection with this piece.

March 28th, 2013 § § permalink

“Hello? Do you have Tilda Swinton in a box?”

For a certain breed of relatively cultured wags (including the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright David Lindsay Abaire and, less exaltedly, me), Tilda Swinton sleeping in a glass box at the Museum of Modern Art is a comedic source that just keeps on giving. After all, this is an Academy Award-winning actor with a distinctly unique personal style ensconcing herself in a terrarium on random days for hours at a time. Modern art, performance art, personal eccentricity or creative vision – all grist for the humor mill. The piece has a name, incidentally — “The Maybe” — which only serves as a dog-whistle call to those who would poke fun at it; that Swinton first “performed” it in 1995 only increases the volume.

I freely admit I am unequipped to assess “The Maybe” as fine art or performance art. But in contrast to my own tweeted gibes and my enthusiastic embrace of David’s seemingly endless variations on the theme, I’d like to dispense with the humor and take the piece vaguely seriously, stipulating to the court that it is worthy of consideration, since experts have apparently deemed it as such.

If it is art of any stripe, why has it touched off such a sensation? If just anyone was asleep, or feigning sleep in a glass box at MOMA for hours at a time, it would be a curiosity, at best worthy of a squib on websites or the kicker story on local news. On occasion, I happen to talk with some coherence while I sleep, and I am known (by a very select few) to thrash about involuntarily as well; I’d be much more engaging lying in that box, but wouldn’t raise much media comment.

If there was no apparent air source to the box, this would rise to the dwindling level of interest of a David Blaine stunt. If there was an adorable kitty or puppy in the box it might find attention as an internet video, or arouse ire and concern over the animal’s treatment. If we learned someone was being paid $50,000 a night to do this, it might prove as enraging as the new Virginia bus stop that cost $1 million to build.

The only reason the general public knows about this piece of art is because Swinton already has a level of fame. She’s got that Oscar and she’s a highly respected actress, though hardly a household name. She might be called a star, but certainly not a celebrity; this isn’t Hasselhoff or a Kardashian lounging about on view. But Tilda’s well enough known to raise oddity into spectacle, more than willing to exploit her renown for this “work,” which has surely generated international headlines for MOMA this week. Let’s remember, when she did this in the 90s, she hadn’t yet gone toe to toe with Clooney onscreen.

Some of the same cultural outlets that are quick to question when “name” actors are announced for theatre productions have covered the Swinton event, and while they’ve noted its peculiarity, many have left the withering and witty comments to those on social media. Silly as the whole thing may seem, I feel they’ve given Swinton some leeway, while shows on and off-Broadway with famous actors are damned right out of the gate as “star-driven,” even when the actor is impeccably cast (admittedly, not all are). No one that I’ve seen has reported the weekend grosses at MOMA, despite their surprise deployment of a celebrity and the subsequent press; however, it is often implied that when a stage piece with a star in it does well at the box office, it has somehow cheated its way to success. Are there different standards for museums and theatres? Or am I just not tuned in to the art world?

To be a celebrity or to be a star, that is the question.

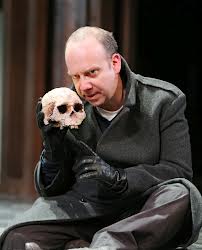

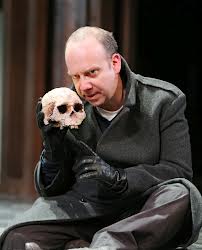

“The Maybe”’s emergence this weekend happened to coincide with the premiere of a new production of Hamlet at the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven. Perhaps you’ve heard about it? Normally, a regional production of Hamlet might not evoke much attention, but this one has lured the New York theatre press onto I-95 and Metro-North almost en masse. Why? Because the melancholy Dane is being played by the very fine actor Paul Giamatti, a screen stalwart little seen on stage in recent years. The announcement of the show generated the first wave of press, given the incongruity of his appearance and manner with most visions of the sweet prince; the performance itself has yielded many more reviews than a typical show at a Connecticut theatre.

Some of the outlets that rushed to see the “famous” Paul Giamatti as Hamlet are the same ones who rail against the damage celebrity casting has done to New York theatre, yet here they are responding to its siren call (along with audiences, who made the show a sell-out even before performances began). I’m not denigrating Giamatti’s considerable talents, but dollars to doughnuts some other fine actor, unexpected or not, but without copious entries on the IMDB, wouldn’t have taxed arts travel budgets. It would have been “just another regional theatre show,” left to the local press.

This is all a long way of saying that whether the box is a small glass display case or grand theatre, fame gets to the head of the media line, even when it comes to the arts, even in media that decry the ascendance of celebrity. I don’t begrudge MOMA or Yale Rep the attention they’re getting, but I wonder whether that attention may play into the hands of celebrity culture, saying to other organizations that they’ll get their shot at the spotlight when and if they too offer the media “names.” Will not-for-profits of every stripe, not just commercial enterprises, be driven towards stunts and stars, even if the examples I’ve given were staged with the utmost sincerity? Or can stardom be made secondary when contemplating the arts?

When we get a gift, part of the excitement is not knowing what’s in the box, the joy of discovery. But if the admittedly embattled media increasingly attends only to boxes – be they glass, canvas, concrete or brick and mortar – because they and we are already attracted to what’s inside, we’ll keep seeing more and more known quantities as companies vie for attention, and without it, it’ll be harder and harder to sustain work that retains the thrill of surprise.

March 6th, 2013 § § permalink

“There is nothing quite as wonderful as money! There is nothing quite as beautiful as cash!”

I have made no secret of my disdain for the practice of announcing theatre grosses as if we were the movie industry. I grudgingly accept that on Broadway, it is a measure of a production’s health in the commercial marketplace, and a message to current and future investors. But no matter where they’re reported, I feel that grosses now overshadow critical or even popular opinion within different audience segments. A review runs but once, an outlet rarely does more than one feature piece; reports on weekly grosses can become weekly indicators that stretch on for years. If the grosses are an arbiter of what people choose to see, then theatre has jumped the marketing shark.

So it took only one tweet to get me back on my high horse yesterday. A major reporter in a large city (not New York), admirably beating the drum for a company in his area, announced on Twitter that, “[Play] is officially best-selling show in [theatre’s] history.” When I inquired as to whether that meant highest revenue or most tickets sold, the reporter said that is was highest gross, that they had reused the theatre’s own language, and that they would find out about the actual ticket numbers.” I have not yet seen a follow up, but Twitter can be funny that way.

As the weekly missives about box office records from Broadway prove, we are in an endless cycle of ever-higher grosses, thanks to steady price increases, and ever newer records. That does not necessarily mean that more people are seeing shows; in some cases, the higher revenues are often accompanied by a declining number of patrons. Simply put, even though fewer people may be paying more, the impression given is of overall health.

I’m particular troubled when not-for-profits fall prey to this mentality as part of the their press effort, and I think it’s a slippery slope. If not-for-profits are meant to serve their community, wouldn’t a truer picture of their success be how many patrons they serve? In fact, I’d be delighted to see arts organizations announcing that their attendance increased at a faster pace than their box office revenue, meaning that their work is becoming more accessible to more people, even if the shift is only marginal. If selling 500 tickets at $10 each to a youth organization drags down a production’s grosses, that’s good news, and should be framed as such, unless our commitment to the next generation of arts attendees is merely lip service.

From my earliest days in this business, I have advocated for not-for-profit arts groups to be recognized not only as artistic institutions, but local businesses as well. While I think that has come into sharper focus over the past 30 years, I’m concerned that the wrong metrics are being applied, largely in an effort to mirror the yardstick used for movies. It’s worth noting that for music sales or book sales, it’s the number of units sold, not the actual revenue, that is the primary indicator of success, at either the retail or wholesale level (although more sophisticated reporting methods are coming into play).

In a recent New York Times story about a drop in prices at the Metropolitan Opera, I was startled by the assertion that grosses were down in part because donor support for rush tickets had been reduced. Does that mean that fewer tickets were being offered because there wasn’t underwriting for the difference in price? Does it mean that the donor support was actually being recognized as ticket revenue, instead of contributed income? What does it mean for the future of the rush program if the money isn’t replaced – less low-price access? No matter how you slice it, something is amiss.

That said, the Met Opera example brings out an aspect of not-for-profit success that is, to my eyes, less reported upon, namely contributed revenue. Yes, we see stories when a group gets a $1 million gift (in larger cities, the threshold may be higher for media attention). But we don’t get updates on better indicators of a company’s success: the number of individual donors, for example, showing how many people are committing personal funds to a group. The aggregate dollar figure will come out in an annual report or tax filing, but is breadth of support ever trumpeted by organizations or featured in the media? I think it should be. I also can’t help but wonder whether proclaiming high dollar grosses repeatedly might serve to suppress small donations.

Not-for-profit arts organizations exist in order to pursue creative endeavors at least in part in a manner different from the commercial marketplace. Make no mistake, the effort to generate ticket sales for a NFP is equivalent to that of a commercial production, but the art on offer is (hopefully) not predicated on reaching the largest audience possible for the longest period possible. When NFP’s proclaim box office sales records, they are adopting a wholly commercial mindset. While it may appeal to the media, because it aligns with other reportage of other similar fields, it disrupts the perception of the company and their mission. And look out when grosses drop, as they inevitably will at some point.

We all love a hit, whether it’s the high school talent show or a new ballet. But if all we can use to demonstrate our achievements is how big a pile of money we’ve made, well then forgive me if I’m a bit grossed out.

January 14th, 2013 § § permalink

“She nailed it! She nailed it! What a spectacular pirouette, Biff, wouldn’t you agree?”

While the idea of all-arts talk radio, modeled on sports talk radio, may strike one upon first thought as rather absurd, I think my friend Pia Catton is really on to something in her enthusiastic pitches for just such a thing both this week and last week in her “Culture City” column at The Wall Street Journal.

Frankly, whether it’s sports, politics or, for that matter, car repair, we’ve been shown time and time again that there are people who are drawn to listen to, and participate in, audio conversations for hours on end. NPR’s Car Talk managed to attract listeners who didn’t even own cars, because the program was simply so entertaining. Now, while the Magliozzi brothers weren’t on a 24-hour car talk network (they had to make room for things like Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me and All Things Considered), their 30 year run is a testament to the idea that good talk makes for compelling listening, no matter what the subject.

So even as yet another arts television network heads towards rocky shoals (Ovation just lost the significant access to the pool of Time Warner Cable subscribers), maybe it’s time to realize that arts TV may be too expensive to sustain. But talking is considerably cheaper to produce, even when done truly well, and if Twitter, Facebook, chat rooms and the like are any evidence, there’s an audience for talking about the arts.

Certainly one fear is that it would quickly devolve into debates about which recording of La Boheme is best, or whose Mama Rose was definitive. I wouldn’t have much patience with such circular argument. But shrewd hosts could prevent repetitive (and insoluble) contretemps in favor of variety, and daily topics and special guests could focus the discourse. This is a little trick known as producing, and while it seems invisible when it comes to talk radio, it’s essential. They’re rarely just turning on a mike and letting some personality do whatever they want, which explains why Keith Olbermann keeps getting fired – he doesn’t want to be produced, but let free to roam wherever he sees fit and get paid for it.

One hurdle to be conquered by arts talk radio is the hyperlocal nature of the performing arts. While the entire country can share movies, recorded music and books, even the most successful Broadway show might be seen by say 500,000 people in a year, meaning that if an arts show is national, you may have trouble finding enough people who have seen any given piece to fuel a great conversation. Though there may be original sports talk radio in many markets, I suspect it corresponds with those markets which have major league teams, even though thanks to broadcast, cable, satellite and the web, sports are accessible across the country as never before.

Because of Pia’s ambition, I’m not prepared to theorize about arts talk radio that only serves New York, Chicago and London even at the start; its greatest service to the arts would be if it was national or international, connecting often disparate arts communities into a single conversation. Where I would moderate her vision is length. A daily show or weekend programming block would be a good place to start and test things out, without round-the-clock pressure and expense.

Another staple of most talk radio is opinion, which can fall somewhere between loud argument over the holiday dinner table and outright character assassination. That worries me. I would have trouble listening to people, whether host or caller, tearing down any artist, even when I agree that their work is negligible. That, of course, is because I come from inside the field. Perhaps, just as with many people’s reactions to the Bros on Broadway on Theatremania, it’s the reflex of the dedicated arts aficionado, protecting the artists and the art, and if arts talk radio is to attract an audience beyond the already-converted, maybe some feelings will have to get hurt, beyond bad reviews.

A number of years ago, I read a fascinating speech given at an arts journalism conference in which the speaker/writer said that if the performing arts want more coverage, more attention and perhaps more acceptance, they need to – to use the sports analogy – let the arts media into the locker room. We are, as a rule, profoundly careful about access to artists and process, so we should be surprised if our coverage is limited to one feature story and one review per outlet. While post-game interviews and sports press conferences are remarkable for their ability to say very little, they create the veneer of connection; if they didn’t, they’d have been axed by editors and producers long ago. Even in film, there are both prepackaged behind the scenes featurettes and set-visits for select outlets, whether high-brow (Vanity Fair) or low (Access Hollywood and the like). Maybe arts talk radio can open up those avenues.

Yes, social media has been used creatively by some celebrities to build the bond with their fans, but most theatre folk don’t manage to reach a critical mass or approach social media all that creatively (on Twitter, Lin-Manuel Miranda offers a great template for artist-fan interaction). They need a platform that goes beyond their own efforts.

Would I have called into arts talk radio when I was 20? Probably so often that I’d have gotten a nickname and become a recurring voice (or gag). Would I do it now? Probably only to play a similar role to that which I play on Twitter: fact-checker, conversation starter, and mild wit. Of course, at this stage, after seven years helming “Downstage Center,” I’d apply for a hosting job in a flash. Frankly, I think Pia and I would make a great duo. And with Car Talk off the air, maybe an arts talk call-in show is just what’s needed. Hmmm.

So I’ve gotta go. Need to find the number for the heads of programming for some radio outlets. NPR, WNYC, WBEZ and WGBH, you’re on the top of the list. Go arts, go arts, gooooo arts!

November 26th, 2012 § § permalink

“Can you imagine the readership if our critics exuberantly hated LOTS of things?”

To begin with, I would like to stipulate that I read Pete Wells’ now-legendary New York Times review/take-down of Guy Fieri’s Times Square restaurant and I found it, as so many did, a striking and funny piece of writing. I read it, I imagine, with my mouth agape, but not watering. I also suspect, based solely on my own street-side reading of the restaurant’s menu before The Review had appeared, that Mr. Wells had more than sufficient grounds for his opinions of the fare. Donkey sauce, indeed.

With that out of the way, I would also like to say that I found The Review inappropriate as journalism, critique or opinionated analysis for the venue in which it appeared. It was, perhaps, more akin to a “Shouts & Murmurs” piece from The New Yorker, fact stretched to its satirical limits. After the first few paragraphs, the point had already been made, but Wells was allowed to go on, and on, to no other end than to demonstrate how skilled and witty a writer he was, and to insure that his evisceration of the establishment left no possible doubt as to how much he had not enjoyed his multiple dining experiences there.

So I was startled when The Times’ public editor Margaret Sullivan, who I have admired greatly since she arrived at the paper, took time to write a Sunday essay which was a full-throated defense of “Reviews With ‘All Guns Blazing’,” because it struck me as just a bit more piling on by the paper of record (yes, I still view The Times that way) without in any way grappling with the deeper ramifications of reviews which don’t merely damn their critical victims, but gleefully turn the knife. Sullivan’s citation of Dorothy Parker’s famed quip about Katharine Hepburn is ironic, because while Parker needed only a few well chosen, subtle words for her takedown of Hepburn, Wells needed, or at least took, paragraphs, when perhaps two would have sufficed. (Sullivan’s defense was also slightly redundant, since her predecessor wrote a piece on the prerogatives of Times critics one day before his departure and her appointment were announced in July; I registered dismay then as well.)

I stand with critics for their right to say what they think, but when that tips over into being clever or cutting for its own sake, I’d like to lobby for erring on the side of restraint. I’m surprised that Ms. Sullivan doesn’t share that view. Reviews occupy a funny place in papers: they’re opinion pieces, although they’re not corralled on the op-ed page; they’re analysis, but based solely on the aesthetic values of the assigned writer, not any defined criteria; they’re consumer reportage unmoored from a narrowly defined constituency. While those in the profession being reported upon can clearly distinguish between a review and straight news or feature coverage, my own anecdotal experience has shown me time and again that average, casual readers often fail to make that distinction. The Times becomes The Borg for so much of its content.

I have read many famous and scathing reviews of theatre productions over the years and they are etched in my brain; Frank Rich on Moose Murders and the musical A Doll’s Life, both read when I was in college, are two that have stuck with me. But once reviews of that type were targeted at my colleagues and my friends as I became a theatre professional, I lost my taste for them; with the benefit of hindsight, of course, I take greater pleasure going over famously misguided reviews. By way of example, time has proven that one can frequently “draw sweet water from a foul well” in the theatre, even though no less than Brooks Atkinson thought it suspect after seeing Rodgers & Hart’s Pal Joey.

I’m even more concerned about the aftermath of The Review: how it “went viral”; how it generated enormous press coverage about the review itself and therefore The Times; how it is now the standard for critical disdain, waiting to be topped by an even more withering and witty assault. In an era when newspapers struggle for relevancy and attention, will the Wells review send the wrong message: that in order for old-line media to break through in the new media paradigm, it needs to become sensational? I’m not suggesting that The Times is about to become a tabloid, but when we start reading about how much of the paper’s web traffic was generated by that review, it’s impossible not to wonder whether some latter-day Diana Christensen isn’t calculating what periodic salvos like Wells’, skipping from department to department, might do for business. Also, with The Times a flag bearer for top-quality journalism, reviews like Wells’ give license to critics at other outlets to make their own writing more outrageous and attention-getting when possible, quite possibly without the talent the Fieri review employed.

“Is it ever really acceptable for criticism to be so over the top, considering that there are human beings behind every venture?,” writes Sullivan. “I think it is. That kind of brutal honesty is sometimes necessary. If it is entertaining, all the better. The exuberant pan should be an arrow in the critic’s quiver, but reached for only rarely.”

I can support brutal honesty. I cannot support gleeful cruelty. Inventive? Sure. Over the top? Too much for a generally sober-sided publication. Piercing arrows in critics’ quivers? Yes. Thermonuclear weapons? No. And who is patrolling the armory at The Times, to insure this isn’t an incipient trend? It wasn’t Arthur Brisbane and apparently it’s not going to be Margaret Sullivan, at least insofar as criticism is concerned. And while it’s hard to muster enthusiasm for standing in any way on the side of Guy Fieri and his emporium, I have to. I may gag at the thought of Donkey Sauce as a food item, but if it were the title of a play or a painting or a book, I’d want that work treated honestly, directly, vigorously, creatively — and negatively if a critic warrants — but not excessively.

UPDATE November 26 at 3:15 pm: After posting this piece, I learned that less than a week ago, The New York Times‘ veteran book critic Michiko Kakutani had written a review of Calvin Trillin’s Dogfight in which she mimicked the book’s own verse scheme, reinforcing my thesis about critics going awry when they work to show their own cleverness rather than attending to the work at hand. Kakutani’s device is hardly groundbreaking; I see it often for works in rhyming couplets both in print and on stage, most notably Moliere and Dr. Seuss. In a bit of irony, she criticizes Trillin’s “unnecessarily blah” rhymes, but apparently sees no problem with her own ostensible rhyming of “shrub” and “flubs” or “oops” and “moose.” Having run only days after The Review, my concern about criticism that values novelty over insight is only reinforced by Kakutani’s poem.

UPDATE November 26 at 3:15 pm: After posting this piece, I learned that less than a week ago, The New York Times‘ veteran book critic Michiko Kakutani had written a review of Calvin Trillin’s Dogfight in which she mimicked the book’s own verse scheme, reinforcing my thesis about critics going awry when they work to show their own cleverness rather than attending to the work at hand. Kakutani’s device is hardly groundbreaking; I see it often for works in rhyming couplets both in print and on stage, most notably Moliere and Dr. Seuss. In a bit of irony, she criticizes Trillin’s “unnecessarily blah” rhymes, but apparently sees no problem with her own ostensible rhyming of “shrub” and “flubs” or “oops” and “moose.” Having run only days after The Review, my concern about criticism that values novelty over insight is only reinforced by Kakutani’s poem.

October 22nd, 2012 § § permalink

What if there were more commandments, but only beyond a paywall?

I have lost the Globe and Mail, and it hasn’t simply been buried under a stack of old magazines. Next week, I lose The Chicago Tribune. I have already begun to mourn.

My losses are not because these newspapers are going out of business. It is because they are moving behind paywalls, as many other papers have done to insure their online content isn’t being read for free, as these companies struggle to remain solvent. Having spent a certain amount of time every morning for the past few years seeking out theatre and arts stories to share on Twitter, I know that the loss of these two outlets will shrink the pool of intelligent coverage from which I can draw. Still, I am sympathetic to the papers, because as I have said before, if we want quality journalism – and I believe we need it – we have to be prepared to pay for it.

But…

Over the past 20 years, long before my Twitter curation, I’ve found the online access to arts coverage from around the country, and the world, to be an enormous asset in my continuing professional education. Indeed, where my only sources for arts news outside of my local paper (wherever I was living) were The New York Times and USA Today (and occasionally The Wall Street Journal), the advent of online newspapers and magazines enabled me to read features and reviews as never before. Yes, Variety had reviews from around the country and a handful of weekly feature stories, the accelerating decline of that publication sapped it of its once essential nature. I suspect I am hardly alone.

Arts coverage on the web eliminated the inefficient need to ask for, or send, coverage around by fax, a highly inefficient samizdat network of like-minded individuals who already knew one another. More importantly, with the rise of social media, it enabled the broad-based sharing of coverage, helping to bring arts aficionados closer with the opportunity to discover and discuss subjects raised in the press regardless of geography and without skipping from website to website in hope of finding worthwhile material.

So how do I reconcile this cognitive dissonance, this belief in paying for good journalism and a passion for access to arts coverage from wherever it may be found?

I’d like to suggest that arts coverage remain free online, unlike the rest of a newspaper’s content. Even as such coverage has diminished and remains under threat (one of the country’s largest cities, Philadelphia, no longer has a full-time theatre critic at any daily paper in the market), newspapers are the last bastion of mainstream arts coverage, long ignored by television locally or nationally.

Precisely because the media has demonstrated or declared time and again that arts coverage does not drive their revenues, I think it should remain free for all, whether to support the groups in its local market or facilitate a national conversation. The Wall Street Journal, despite its trendsetting paywall success, maintains its arts blog, “Speakeasy,” outside of access restrictions, and while I would like more of its arts content readily accessible, they’ve at least set a precedent, with no apparent financial harm.

Even as a die-hard consumer of arts coverage, I’m not about to pay $10 or $15 per month to read about what’s happening in Chicago or Toronto in these paywalled publications, especially if I can’t share it. I’ll find at least some of that news through other sites. But as someone living hundreds of miles from these cities, if outlets are fundamentally opposed to any free access, I can’t help but wonder whether something equivalent to sports broadcast blackouts could apply; you pay if your IP address is located within 90 miles of the publication’s base, but those outside that circle have vastly less expensive access.

There’s a double-edged sword to hiding arts coverage behind paywalls. On the one hand, the publication may be securing its revenue base (although it may be forcing people to unprotected news resources elsewhere in the market). But in the case of arts coverage, it may well drive the growth of new online-only resources, creating a viable market for arts-specific sites – thereby advancing the irrelevancy of what the paper is providing for a steadily diminishing audience. That will then serve as the excuse to further cut arts coverage.

Am I anti-blog or online magazine? Hardly. But outside of a handful of online publications that do include arts and culture coverage (Slate, Salon and Grantland come first to mind), the majority of what is out there isn’t economically viable, and therefore relies on unpaid (read volunteer or self-produced) coverage, limiting its long-term prospects. Are there superb blogs? Absolutely. But when they write about anything beyond their own immediate vicinity, they’re predominantly relying on other outlets for the news upon which they then re-report or opine.

It’s ironic that I write this while living in New York City, which offers more variety of daily and weekly arts coverage than most cities. But as I hope I’ve shown in my writing, I don’t consider New York as the be-all and end-all of the arts; there’s superb work worth seeing, or at least knowing about, everywhere. Yet with each paywall announcement, I feel my world narrowing, headed backwards to the pre-internet era, and it troubles me greatly.

I urge those who have or would have paywalls to continue to treat the arts as a loss leader and maintain that coverage online for free or almost free, outside of local and national news, business coverage and sports. You’ll keep America’s arts healthy by providing the raw material of national conversation and you’ll make sure that we’re talking about you, too. Because you want to remain part of the conversation too, don’t you?

July 16th, 2012 § § permalink

It cannot be easy being a “public critic,” or ombudsman, so I have a certain sympathy for Arthur Brisbane, The Public Editor of The New York Times. Although he is in their employ, he is charged, as I understand it, with acting as the voice of the people at the paper, exploring issues and practices at the paper independent of the regular news and editorial staff. The practical, personal, professional and ethical issues are complex, no doubt, and it’s worth noting that the paper’s first Public Editor, Daniel Okrent, has turned to the comparably relaxing world of the professional theatre as an alternative.

But despite this sympathy, I have to say that The Public Editor’s newest work, “The View From The Critic’s Seat,” is a disappointment. While written with Brisbane’s usual clarity, it sets up a premise and then utterly fails to address it, leaving this audience member to wonder whether late cuts muted his commentary or whether he simply wasn’t able or willing to confront head on an issue which he himself had highlighted.

In his first act, running a brief 5.5 column inches, Brisbane relates stories of readers who have expressed their displeasure with the tone of several articles in the arts pages of the Times. Since none of those he cites are a Mr. Richard Feder from Fort Lee, NJ, I have to trust that these are direct quotes from actual readers, not composites or inventions. The readers expressed reservations about pieces on the singer Jackie Evancho, principal dancers in a performance of “The Nutcracker,” and the late artist LeRoy Neiman. I know little of the work of the first artists’ named; my closest connection to Mr. Neiman was a free Burger King book cover I received sometime in the early 1970s, adorned with Mr. Neiman’s Olympic art. Therefore, my response to the column is not compromised by any personal feelings about those discussed by The Public Editor.

But after setting up the premise that he will address what some readers see as unduly harsh assessments of artists, Mr. Brisbane pivots suddenly, referring to complaints about criticism as “a certain backwash of discomfort,” employing a negative, unappetizing metaphor unilaterally to this particular subgenre of reader correspondence. He then ceases to utilize his own ostensibly opinionated voice for his disproportionately long Act II, preferring instead to dedicate some 17 column inches to the culture editor Jonathan Landman discussing the scale and challenge of covering all that the Times culture desk endeavors to encompass. And while the scale is almost certainly as wide ranging and logistically complex as Mr. Landman asserts, it has absolutely nothing to do with the issue of opinions which may step beyond an undefined line of propriety and into character assassination.

It’s a shame that The Public Editor didn’t go beyond a single source, since within his own paper he can find evidence of ethical quandaries when it comes to authors personal opinions, what appears in the paper and what is appropriate. Perhaps Mr. Brisbane might have explored Charles Isherwood’s declaration that he no longer wished to review Adam Rapp’s plays, an internal issue given a public airing that allowed Mr. Isherwood the opportunity to once again cast aspersions on the work of an author even as he was saying that he no longer wished to be forced into the position of casting comparable aspersions.

That aside, it is the inexplicable avoidance of the very topic he sets up that proves such a letdown and, as if to exacerbate matters, he tosses in a coda at the end of his encomium to the Times cultural reportage saying that it “should never come at the expense of the subject’s dignity.” Well, has it, Mr. Brisbane? Has it? Had he spoken to the various subjects of Times criticism, or conversed directly with the letter writers, I suspect they could have given him numerous examples where they feel that line was crossed, so that Mr. Brisbane could have made his own assessment.

The Public Editor’s column can, at his or her discretion, be a monologue; in this instance it was a two character piece adopting the form of an interview. Had Mr. Brisbane chosen to bring in the active voices of others who are affected by this issue, and not simply spoken with Mr. Landman and quoted from letters, he could have provided a compelling picture of the ongoing struggle between arts and critics, newspapers and their public, and perhaps even between a Public Editor and his employer.

Despite his hagiography of the Times culture section, which I also admire, I shall continue to follow The Public Editor’s work with interest, in the hope that he will challenge authority, play devil’s advocate and on occasion ruffle a few feathers. For those of us who care about (and pay for) quality journalism, The Public Editor has the potential to be one of the most valuable voices in journalism, as a check and balance against the reporting of the news itself.

Update, July 16 at 1 pm: Timing, as they say, is everything. Barely two hours after I posted this piece, The New York Times announced that Arthur Brisbane would be succeeded as public editor by Margaret M. Sullivan. While my criticism of yesterday’s column by Brisbane stands, so do my hopes for the role of the Public Editor and, therefore, Ms. Sullivan. I look forward to her tenure, which beings in September.

May 23rd, 2012 § § permalink

Followers of the ethical issues surrounding the press in general, and arts journalism in particular, spent the first few days of this week watching and opining on Peter Gelb’s decision to remove reviews of The Metropolitan Opera from Opera News and his decision, only a day later, to restore said reviews, amidst an almost unanimous outcry against his maneuver. Gelb’s efforts inspired sufficient umbrage that even when he reversed his decision, people then criticized him for folding so quickly and not having the strength of his own convictions.

As a result, you may be unaware of another critical contretemps that has set the theatre world abuzz – the Australian theatre world, that is. This past weekend, the stage musical of the film An Officer and a Gentleman opened in Sydney, Australia (please, hold your contempt for musicals derived from movies for the moment). This opening was a source of national theatrical pride, as Australia seeks to bolster its image as the starting place for major musicals, a position declared in the pages of Variety only last week. Priscilla Queen of the Desert and Dirty Dancing, also film-derived, are two previous productions cited. With the advent of the internet, going out of town to work on a show without press scrutiny has become increasingly difficult. Australia is seeking to supplant the West Coast of the U.S. as a place where one can go relatively free of prying eyes.

So what’s the fuss? The Australian, a national daily, first published a short review on May 19 critical of the musical and, on May 21, the same critic reinforced her views with a longer piece. But on the 21st, The Australian also saw fit to publish a letter from Douglas Day Stewart, screenwriter of the film and co-writer of the book of the musical, in which he lashed out strongly at The Australian’s review and its critic, going so far as to suggest that she is “incapable of human emotion.” Because I have seen this coverage on the Internet, I do not know the relative prominence each piece received in print, although it is fair to say that The Australian sought to provoke controversy, since they could have declined to run the letter.

Now artists writing to newspapers to complain about reviews is hardly a new phenomenon. It’s not hard to understand why someone involved in a creative venture would feel compelled to try to debunk not only criticism but the person who wrote it. After all, no one likes being told their baby is ugly. However, in my experience, it’s an impotent gesture at best and a counterproductive one at worst: I am unaware of any critic ever seeing such a missive and then realizing that they were “mistaken.” More often, the critic will respond to such letters by reiterating or embellishing upon their original position, and the artist doesn’t get a second whack. The critic may harbor resentment, to be expressed in the future, against the artist or the producer, whether commercial or not-for-profit. When this sort of thing has come to me as press agent, as general manager, as executive director, I have always sought to talk the artist down, expressing genuine compassion, but trying to explain that other than making themself and perhaps the company feel better, no real good comes of such an action.

When this first blew up in Australia, several of my Twitter friends down under were quick to send me various links, saying, more or less, “Have you seen this?” My initial reaction was to not comprehend why this perennial conflict merited much attention, but consistent replies said that, indeed, national pride was at stake. If that’s the case, then it is unfortunate that so many people have invested emotionally in the current state of Australian theatre through this one production – and even more unfortunate that Mr. Stewart (Mr. Day Stewart?) caused more attention to be focused on An Officer and A Gentleman. The fact is, were it not for his letter, this opening might have escaped me (and no doubt many others internationally) entirely and the show would have been free to develop in relative solitude. Instead, it’s now “the show where the author got mad at the press.” By citing “a plethora of five-star reviews,” Stewart sent many looking for them, and let’s just say I hardly found a “plethora.” (For your reference, here are a selection of reviews from: The Daily Telegraph, The Sydney Morning Herald, Australian Stage, Crikey, Nine to Five, and The Coolum News)

Thanks to Mr. Stewart, my sense of An Officer and a Gentleman is that it did not meet with general critical acclaim, save for The Australian, but (thanks to comments beneath reviews) that it is a crowd-pleaser. If the creative team feels they have an impeccably wrought success and feel no further work is necessary, the show may be a risky venture based on what I’ve read. The more strategic response to the reviews, if there was to be a response, would have been to talk about the value of many opinions, critical and general public, and talk about how the time in Australia was going to be used to make the show even more successful and entertaining before conquering the known world.

Like the Gelb incident, the Officer and a Gentleman kerfuffle is a result of people not thinking through their actions fully in advance, perhaps not seeking (or accepting) the counsel of others, to the detriment of their institution or their production. The Metropolitan Opera will go on, and it’s very likely that An Officer and a Gentleman will be seen in other countries one day soon. But in both cases, focusing on the productions instead of the press would have been more, well, productive.

April 24th, 2012 § § permalink

It’s a word that is thrown about with abandon. “Flop.” It is synonymous with failure and it’s one of those words that sounds like what it means: short, blunt, unimpressive; the sound of a leaden landing or even the puncturing of expectation.

It is used profligately in the theatre, and indeed aficionados revel in tales of famed flops on Broadway: vampire musicals, Shogun, Carrie, Enron, On The Waterfront, Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Even as you read this, you’re adding your own to the list. Theatrical dining spot Joe Allen reserves space on its walls for posters of famous flops (also accessible online); I have to imagine it has either driven away those who were involved in these shows, or at least induces a bit of indigestion as they dine.

There’s a certain grandeur and folly to the theatrical flop. There are countless shows that over the decades have opened, often with big stars and advance anticipation, only to sink quickly out of sight. But to be a truly legendary flop, there seems to be a unique and ever changing set of guidelines that lifts this show or that one into the pantheon; certainly hubris seems to play a role. The more godawful, the better they are for gossip and chatter, years after the fact. Even Shakespeare can flop on Broadway, despite the long-established reputation of the work; living down to its cursed reputation, separate Macbeths featuring Kelsey Grammer and Christopher Plummer come to mind.

Yet for some, notably journalists of a certain vintage, “flop” is not merely a pejorative, but an economic distinction, propagated by the much diminished show biz bible Variety. Any commercial production that does not recoup its initial investment during its Broadway run, even if only shy by five or ten per percent of the capitalization, is a flop. Any show which recoups or exceeds is a hit. This rigidly binary criteria permits no flexibility, so some of Stephen Sondheim’s most admired work takes its place alongside travesties in the Variety annals; flop is an economic distinction, not an artistic one.

I have no doubt that this terminology, part of the distinctive patois that made Variety such a pleasure to read (and commemorated by Animaniacs as “Variety Speak”) dates back many decades, to a time when all major new work debuted on Broadway and the not-for-profit theatre system in America was not yet formed (most agree it launched in earnest in the early 1960s). So does – and should – “flop” retain any power today? There’s certainly no eradicating the word (any more than the failure to nominate certain artists and works for awards will cease to be called “snubs”), but perhaps we can all agree that there’s a benefit to discussing the success or failure of theatre with something approaching nuance.

On a purely economic level, the failure of a show to return its entire investment during its Broadway run does not mean that the show is necessarily unprofitable. Yes, shows that lose their entire investment or return only 30% of the capitalization have a very long road, especially musicals produced for $10-15 million. But what of those shows that get to 85% or 90% recoupment? They are likely to tour; to be licensed to regional theatres, amateur companies and schools; to sell cast recordings even if they didn’t quite snatch the brass ring in the commercial incarnation. Maybe they’ll even be sold to the movies. As a result (and I’m not going to break down how investment income is returned to investors and producers in this post), they may enter profit a year or several years after they’ve shuttered on Broadway. But the public books have already been closed, the rubber stamp of flop already impressed upon their public file; no one issues press releases about recoupment on closed shows (though perhaps they might do well to start).

This isn’t as much of a problem for the not-for-profits that produce on Broadway, or for that matter, Off-Broadway. Since their expenses for any show are part of a larger institutional budget, the issue of recoupment isn’t germane; in their immediate wake, an unpopular show may be branded a flop, but over time that distinction seems to fade in a way it does not for commercial work. This doesn’t stop the media from trying to intimate the dreaded branding iron of flop when discussing not for profit work; witness The New York Times’ “autopsy” for MCC Theatre’s Carrie revival, which wishfully applies the paper’s own commercial expectations for the show in order to support its thesis.

“Flop” strikes me as particularly debilitating when it comes to work that is recognized as having artistic value, even if it fails in the marketplace. As far as I’m concerned, Sondheim’s score for Merrily We Roll Along is one of his finest and while the overall piece proves problematic in reworking after revival after resuscitation, I challenge anyone who would claim that it is an utter failure creatively, even if it is not an unqualified success. By Variety’s yardstick, the original Merrily was a flop, and it’s hard to argue given its brief run, but that fails to do the work justice. If one is allowed more than a single word in judgment, it is an ambitious, flawed work by one of the geniuses of musical theatre; it does not deserve dismissal in a column that codifies only hits and flops. Works of art shouldn’t be “guilty” or “not guilty.”

“Flop” is so associated with theatrical ventures that Dictionary.com goes so far as to help define its meaning by specifically linking it to works on the stage; I can’t compete with that. But perhaps in our conversations in the field, commercial or not for profit, we can bring shadings to assessments of productions. For economics, we must take the long view, and remember that a show’s life does not end the moment it closes in New York. For creativity, I recommend that The Scottsboro Boys, Caroline or Change and Passing Strange shouldn’t be lumped together on any extant list with In My Life and Metro. We would serve work better – even when money is lost, sometimes significant sums – if our collective focused on the succès d’estime, rather than the success of an accountant’s pen. It won’t necessarily cushion financial losses, however they’re calculated, but it will put emphasis back on the work, not just on its bottom line.

April 9th, 2012 § § permalink

O.K., so it’s not “This Is Your Pilot Freaking.”

Though I see journalism and criticism discussed and dissected six ways to Sunday in article upon article, blog after blog (and I’m often an avid participant), headlines tend not to be a significant part of the discussion of arts journalism. The “star rating” system gets a lot more attention, as of course do the reviews themselves. But headlines can have an enormous impact on your impression of a review, or a show; like stars, headlines may, for an enormous number of readers, be all they ever learn about a show.

Good headline writing is a talent, a craft, and that holds true in old-line print media or online. The Huffington Post seems to have made its fortune on headlines that promise more than they deliver, harking back to the best of true tabloid journalism, but dammit they make you look. None of us are immune to the lure of shrewd headline.

As someone who surveys the internet daily for news stories of theatrical interest, I marvel at the headlines I see, some clever, some mundane, some inadvertently hilarious. While there are fine editors of all stripes who contribute to headlines (the general public doesn’t realize that in many cases, the writer of the article has no participation in the process), there’s no question that at smaller outlets that still generate a lot of copy, the process of headline writing can become a bit rote. In the most absurd cases, I envision a lone editor, late at night in an empty newsroom, wracking their brain for copy that will fit both the story and the allotted space.

My imagined editor seems to work on a lot of theatre reviews but apparently doesn’t go to a lot of theatre, and so I muse upon headlines I suspect most of us would not want to see; endless alliteration, bad puns, inadvertently risqué or even offensive juxtapositions pouring from a sleep-deprived mind, one that may have only read the review cursorily. Consequently, here’s a selection of 25 headlines I created for a range of plays and musicals – all to accompany positive reviews, as going negative is too easy – with the hope that it will make its way to arts copy desks across the country as samples of what not to do. But I can assure you that these are very close to the reality I see daily.

- Where’s the beef? Steer yourself to prime AMERICAN BUFFALO

- Don’t paws, run to (litter) box office: CAT on TIN ROOF will have you feline HOT

- Fine end to CORIOLANUS, but you may be bummed out

- Insane fun to be had at nutty CRAZY FOR YOU

- Miller spins tight-knit yarn about SALESMAN’s DEATH

- Piercing EQUUS quiets the neigh-sayers

- No woe at MOE show, so grab FIVE GUYS and go, shmoe

- Kernel of corporal punishment makes LIEUTENANT OF INISHMORE generally great

- LITTLE WHOREHOUSE turns tricks into trade, hooks audiences to happy ending

- Compelling climax in THE ICEMAN COMETH

- You’ll want to preserve JELLY’S LAST JAM

- No need to hope for charity at LEAP OF FAITH

- NIGHT time is the right time for Sondheim’s MUSIC

- Oh, my: THE LYONS is a tiger, bears seeing

- Missed I and II? You’ll still enjoy MADNESS OF GEORGE III

- MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM is tops

- M. BUTTERFLY emerges in unexpected, satisfying ways

- Start spreading the NEWSIES

- NORMAN’s CONQUESTS make him Attila the Fun

- ONE MAN, TWO GUVS: three cheers four you — five stars

- Norris’ PAIN AND THE ITCH receives critical an-ointment

- Local troupe puts impressive PRIVATES ON PARADE

- Current RAISIN IN THE SUN prunes away time’s overgrown vines

- There’s no need to fear, TOPDOG/UNDERDOG is here

- Yes VIRGINIA, Albee’s foxy WOOLF blows the house in

I will close by quoting a long-remembered headline, 100% accurate, that accompanied a glowing review for a show I worked on once upon a time: “Crawl Over Ground Glass to See This Show.” Enticing, huh? Truth can be stranger than fiction.

Nonetheless, now it’s your turn. Can you craft some headlines that stumble on the fine line between clever and stupid?