September 4th, 2015 § § permalink

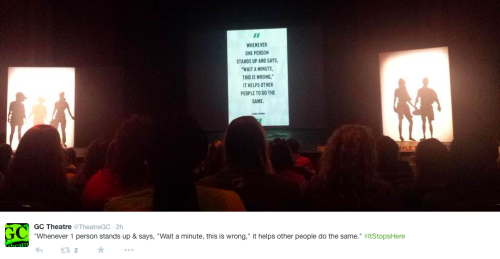

Poster from It Stops Here at Greensboro College

Members of the Greensboro College community have the right to be free from gender-based discrimination, sexual harassment, and sexual misconduct of any kind.

– from the Greensboro College Sexual Misconduct Policy

To start the new school year, Greensboro College in North Carolina required all of its first-year students to attend a performance of It Stops Here, a play about sexual violence, as part of the college’s newly adopted Sexual Misconduct policy. If that were all there was to report to illuminate how, beyond online training and in-person seminars, the school was employing theatre – a student written and directed play, no less – to confront this topic, it would be a terrific example of the power of theatre. Instead, the first performance of It Stops Here resulted in the harassment of the students performing the play and the opening of a Title IX investigation on the campus within 24 hours of that first presentation. It showed that even the dramatic rendering of sexual violence and its aftermath could provoke vocally insensitive, deeply offensive responses among first year students, and that despite the new steps taken by the school, many more were needed.

* * *

In presenting It Stops Here, a project of the college theatre department, it appears that the school’s primary concern was the potential to provoke deeply felt emotional responses in the audience. The play combined the words of the playwright with monologues from survivors of sexual assault that were submitted for use and presented verbatim. There were “trigger warnings” on the show’s promotional materials and an announcement prior to the performance; students acting as ushers were stationed in the aisles with flashlights to immediately assist any student who was overcome and needed to leave quickly.

The production had its first performance, a preview really, at 11 am on Wednesday morning this week, with students required to attend as part of their first-year seminar classes, an ongoing orientation program on how to succeed in college, as the school president described it. Teachers and coaches were to attend with their students, so that the show might provide the basis for further conversation.

“There was a certain segment of the audience that was joking and making crude remarks,” said Luke Powell, a senior theatre major who appears in the play. “One of the first things I noticed was during one of the monologues. One of the girls was doing hers and I could hear that this portion of the audience was catcalling her during this story of a rape victim. That really set me off, because it’s really disrespectful.

“The worst thing that happened,” Powell later said, “was when we get to the end of the play, the stage goes dark and four of the girls do the internal thoughts of a victim during a sexual attack. Some of that group got up to leave, not because they were triggered. Some of the group was saying stuff like ‘oh, you want it,’ and one started making a noise with his hands that sounded like masturbation throughout the five or six minute scene.”

“I expected this to happen,” declared Makenzie Degenhardt, a sophomore theatre major who appears in the play. “It’s a topic people don’t like to talk about. As soon as someone says rape, people get uncomfortable. People make jokes about things they’re uncomfortable with, but in this case it was inappropriate.”

Dagenhardt described hearing, “laughing and reactions that were not appropriate. People were laughing, clapping and encouraging behavior that shouldn’t be happening.” As to how the behavior affected her own performance, Dagenhardt said, “It made me speak louder. When I’m walking down the street and a boy catcalls me, I just ignore it, so I spoke louder to make sure I was heard. I was appalled.”

Dagenhardt said that her initial reaction was, “Oh, boys react like this, this is normal.” But upon reflection she realized, “It shouldn’t be normal. That’s what the point of the show is. If it happens again, I will respond differently.”

Another actor in the play, Emily Parker, a junior theatre major concentrating in musical theatre performance, described being on stage with a male scene partner. “A particular group of boys was talking rudely,” she said. They were talking loudly about how they didn’t want to be there and how they thought he [the male actor] was gay. Typical teenage boy stuff. “He’s so gay’.”

Ana Radulescu, a freshman theatre major concentrating in directing, who was the assistant director for the show, watched from the back of the house. She described the behavior of one pocket of students during the same scene that Dagenhardt referred to. “They did call him a ‘fag’,” she said. “He had a line that said ‘No one in high school ever told me I would have a girlfriend,’ and a bunch of people around me just started laughing.” Radulescu also described hearing a student, as a female actor was speaking on stage, speaking only partially in a whisper to those around him, say, “Whore. Bitch.”

Radulescu also said that another student, seated near where she stood at the back, before the show the show had even started, declaimed things like, “It was consensual – I didn’t rape her” and “I did Haven, I promise.” Haven is the online sexual harassment training all students were required to complete.

* * *

Of the five students who spoke on the record for this article, all of them expressed disappointment at the fact that while there were faculty in the theatre during the performance, they were unaware of any efforts by those faculty members to curtail the behavior that continued throughout the show. Several students spoke specifically about the lack of action by the Dean of Students, who they say was seated close to the area that harbored the worst offenders, and couldn’t have possibly missed what was happening. Some students also said that there was less faculty than anticipated, saying that not all of the instructors who were supposed to attend with the students, in order to facilitate subsequent discussion, had been present.

The students who were in the show all expressed, in differing ways, their own indecision about what to do in the face of inappropriate behavior and language. Emily Parker said, “We were in a predicament over whether to confront it or go on with the show.”

Backstage, Rebecca Hougas, a freshman theatre major concentrating in theatre education, was working as assistant stage manager, and said that for much of the play, she wasn’t aware of what was taking place, until late in the show.

“I could hear laughter,” she said, “and I knew this was not a laughing matter.” Hougas said that she really came to understand what was going on by seeing how the actors, who were onstage for most of the performance, reacted when they came offstage. “We had one actor come off the stage in tears over what she was trying to say.”

Several students spoke of actors being physically ill after the performance, and of the company coming together to support one another. Those I spoke with say they were upset upon leaving after the show, even as they had banded together to support one another, but not expecting any significant further fallout from the incident.

* * *

I first learned of what had happened at the performance of It Stops Here when, the next day, playwright and advocate Jacqueline Lawton sent me a Tumblr post recounting the event, written by Nicole Swofford, a recent graduate of Greensboro with a theatre degree who is still close with some of the students involved in the production. It described many of the same incidents that were ultimately described to me, but Swofford was also reporting what was said to her, as she hadn’t been at the show.

Swofford was very clear, and very honest, about her intent is posting, writing:

“Greensboro College is a small private college with less than 2,500 students and there hasn’t been a sexual assaulted recorded in the official report in years. Which is a blatant cover to protect the school from getting into to more hot water than it already is (having suffered from lots of financial problems in the past).

This is disgusting, and as a survivor of my own assault, and an alumni of this school I am appalled. All I can ask is that you share this story with everyone, and realize our fight is far from over.”

She had written on Wednesday evening, and her post, along with Facebook posts and comments about the incident, circulated quickly around the campus.

* * *

Where this story may differ from other accounts of sexual harassment on college campuses is that, less than 24 hours after the performance, the school opened a Title IX investigation. It did so on its own, not as a result of a specific complaint by a student, faculty or staff member. It is quite possible that this was because students reported Greensboro’s Title IX Coordinator, Emily Scott, as having been present at the performance. Her title at the school also includes “Assistant to the President.”

As information was being routed to me, but before I spoke directly with anyone on campus, a statement from the college president, Dr. Lawrence D. Czarda, addressed the issue in a school-wide communication:

“It has been reported that during a special performance Wednesday of the play “It Stops Here” for First Year Seminar classes, several audience members made comments that were offensive and sexual in nature. Under our new Sexual Misconduct policy, the comments that have been reported qualify as sexual harassment. The Title IX Coordinator has reviewed the reported comments and has asked the Title IX Investigator to gather additional information to determine who is responsible for making the comments. The college is pursuing a formal complaint of sexual misconduct against the students and is working to identify them. Upon results of the investigation, those found responsible will face disciplinary consequences.”

He also wrote:

“However, Wednesday’s incident makes clear that we as an academic and social community still have much to learn. That includes all of us, not just a few students. In addition to the Title IX investigation, the college will be reviewing and discussing the entirety of the context of the incident. Among many other questions, we will address such issues as what faculty and staff who were present might have done differently. Beyond meeting our legal obligations, the College’s goal is to make this incident a learning opportunity for the entire College community.”

When I spoke with Dr. Czarda, he volunteered that, “We do not have a history of sexual assaults on campus.” But he said that in response to the national dialogue about sexual violence, “the board adopted new policies which were put into place July 1. All students were required to take an online training course before the process of moving in. In addition, all students are required to do an on-site training program. All faculty and staff were required to do online and in-person training sessions. The fact that the student production is part of the required training means they’ve heard what these issues are about.”

When asked about what kind of preparation students had been given prior to seeing the play, he cited the online and in-person sexual misconduct training implemented by the school. “Did they know specifically what was going to happen on stage?” Dr. Czarda asked rhetorically, suggesting that they didn’t, that students attended the show without any direct contextual preparation prior to attending. But he said, “I think we did a tolerably good job in prepping the students.”

As to why no member of the faculty or staff intervened in light of the catcalling, insults and disruptions, Dr. Czarda said that was a “key question.” He said, “On the one hand, I have been told that there was some behavior that was not atypical of freshmen,” but he said, “I have not talked to any faculty or staff who heard the comments being made. I’m very troubled by that.” As to whether all faculty who we supposed to attend had done so, he said, “I hope that is not the case.”

Regarding steps being taken to insure that the incident would not recur, Dr. Czarda said that there would be campus security and faculty at every performance; he attended last night’s show. “We will have a very clear, immediate response,” he stated. “I would be totally disheartened and shocked if anything like this happened again.”

The students told me that they had agreed that if there were incidents at subsequent performances, they would simply pause in place until it ceased; some said they might direct their looks to where the believed the interruptions to have come from. Several, jokingly, invoked the name of Patti LuPone and her cellphone incident of earlier this summer.

Luke Powell subsequently reported that the Thursday evening performance had taken place without incident. “I’ve never seen an audience give a standing ovation so quickly,” he wrote.

* * *

As readers can tell from this account, some students who were a part of It Stops Here took me up on my offer to speak with them, others obviously did not, and I don’t think anyone should infer anything from the fact that I did not hear from some. That is their absolute right.

As readers can tell from this account, some students who were a part of It Stops Here took me up on my offer to speak with them, others obviously did not, and I don’t think anyone should infer anything from the fact that I did not hear from some. That is their absolute right.

Because institutionally, it is so often the case that in the midst of a crisis organizations initially go silent, trying to decide the best course of action, I have to say that Dr. Czarda’s willingness to speak with me within three hours of my request was both surprising and appreciated.

But I now want to say to Dr. Czarda something I didn’t express when I spoke with him, in part because by the time we spoke, he was getting organized to attend last night’s performance and had limited time. I want to say that while he may be technically correct when he says there is no history of sexual assaults on his campus, that does not mean there haven’t been sexual assaults on his campus, only that they have gone unreported, that they are not part of the school’s records.

Statistically, both on campuses and in the population nationally, sexual assault is too widespread to imagine that Greensboro is a unique sanctuary. Students up until now may have been too afraid, may have been too intimidated, may not have seen genuine evidence of support and understanding in the school environment, prompting them to keep silent. If the prevailing attitude is “it doesn’t happen here” and if the new guidelines have been put in place only to comply with general practice and to insulate the school from future liability, not because of a deep understanding of the prevalence of sexual violence, then there is still a great deal more learning to be done, and not just by the students of Greensboro.

The students I spoke with were uniformly appreciative and indeed surprised by the speed with which the school began its investigation. However, several expressed concern that because the perpetrators sat in the dark and were not immediately discovered and taken out, no one will ever be held accountable. Greensboro College is now on the line both in terms of how it addresses this current situation and what it does now that it has learned that its newly implemented policies are clearly insufficient.

I would also be remiss if I didn’t say to Dr. Czarda and the Greensboro faculty that the students are not only concerned about getting through the performances this weekend. While one noted that they feel “more comfortable knowing that some of the faculty is stepping up and doing their job” and that “the regulations are going to make sure this doesn’t get swept under the rug,” there are now students on your campus who are concerned about recriminations and retaliation because they spoke up, because they spoke out. Beyond insuring the performances go forward smoothly, beyond investigating what took place on Wednesday, you now must do everything possible to make certain that all students connected with this production, and indeed all students (and faculty and staff) are safe and secure on your campus, in the days, weeks and months to come.

What happens at Greensboro in the wake of this incident is not simply a campus matter, but one with impact on every college campus, and for every survivor of sexual assault and their families and friends. If this is what happens when sexual assault is portrayed, what will happen if – and indeed, sadly, when – sexual violence occurs? The school has already been made an example. Now it must demonstrate whether it can set one.

* * *

When asked whether they thought that the rest of the audience at Wednesday’s performance had gotten the message of the show, several of the students professed somewhat ruefully that they didn’t know; one said she knew of one student who had expressly communicated how important it had been for her. If the remaining three performances go as well as last night’s did, then hopefully the message of the play will be reaching many more members of the Greensboro College community in the way it was intended to do.

At the conclusion of our conversation, Ana Radulescu summed up so much of what is essential now in regards to Greensboro and It Stops Here.

“We all now understand what those girls who sent us those monologues were talking about. In a way, we were all sexually harassed yesterday and this Title IX report says so. I never knew that through theatre someone could be harassed. Now in six hours, I understand a lot more of what comes out of those girls’ mouths.

“The idea of this piece is to start this conversation. I don’t think we planned on it starting this way. But if you want to look at it, it’s nothing different than what we meant it to do. The fact that it’s not getting ignored is sort of amazing. It has reaffirmed for us that the piece needs to happen, why it needs to happen and why it needs to happen here. If anyone questioned that, well – we have the answer.”

Update, September 5: A local television newscast covered the incident at Greensboro College last night. You can view their report here; the video piece is more complete than the accompanying text.

The title of the play discussed in this post is shown on the poster as “It Stops Here” with a period at the end of Here. The punctuation mark has been omitted from the text for clarity.

I attempted to reach the theatre department chair David Schram and Josephine Hull, assistant professor of acting and voice, but neither replied to my inquiries.

This post will be amended and updated as the situation warrants.

Howard Sherman is the director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School for Performing Arts.

September 4th, 2015 § § permalink

Members of the Greensboro College community have the right to be free from gender-based discrimination, sexual harassment, and sexual misconduct of any kind.

– from the Greensboro College Sexual Misconduct Policy

To start the new school year, Greensboro College in North Carolina required all of its first-year students to attend a performance of It Stops Here, a play about sexual violence, as part of the college’s newly adopted Sexual Misconduct policy. If that were all there was to report to illuminate how, beyond online training and in-person seminars, the school was employing theatre – a student written and directed play, no less – to confront this topic, it would be a terrific example of the power of theatre. Instead, the first performance of It Stops Here resulted in the harassment of the students performing the play and the opening of a Title IX investigation on the campus within 24 hours of that first presentation. It showed that even the dramatic rendering of sexual violence and its aftermath could provoke vocally insensitive, deeply offensive responses among first year students, and that despite the new steps taken by the school, many more were needed.

* * *

In presenting It Stops Here, a project of the college theatre department, it appears that the school’s primary concern was the potential to provoke deeply felt emotional responses in the audience. The play combined the words of the playwright with monologues from survivors of sexual assault that were submitted for use and presented verbatim. There were “trigger warnings” on the show’s promotional materials and an announcement prior to the performance; students acting as ushers were stationed in the aisles with flashlights to immediately assist any student who was overcome and needed to leave quickly.

The production had its first performance, a preview really, at 11 am on Wednesday morning this week, with students required to attend as part of their first-year seminar classes, an ongoing orientation program on how to succeed in college, as the school president described it. Teachers and coaches were to attend with their students, so that the show might provide the basis for further conversation.

“There was a certain segment of the audience that was joking and making crude remarks,” said Luke Powell, a senior theatre major who appears in the play. “One of the first things I noticed was during one of the monologues. One of the girls was doing hers and I could hear that this portion of the audience was catcalling her during this story of a rape victim. That really set me off, because it’s really disrespectful.

“The worst thing that happened,” Powell later said, “was when we get to the end of the play, the stage goes dark and four of the girls do the internal thoughts of a victim during a sexual attack. Some of that group got up to leave, not because they were triggered. Some of the group was saying stuff like ‘oh, you want it,’ and one started making a noise with his hands that sounded like masturbation throughout the five or six minute scene.”

“I expected this to happen,” declared Makenzie Degenhardt, a sophomore theatre major who appears in the play. “It’s a topic people don’t like to talk about. As soon as someone says rape, people get uncomfortable. People make jokes about things they’re uncomfortable with, but in this case it was inappropriate.”

Dagenhardt described hearing, “laughing and reactions that were not appropriate. People were laughing, clapping and encouraging behavior that shouldn’t be happening.” As to how the behavior affected her own performance, Dagenhardt said, “It made me speak louder. When I’m walking down the street and a boy catcalls me, I just ignore it, so I spoke louder to make sure I was heard. I was appalled.”

Dagenhardt said that her initial reaction was, “Oh, boys react like this, this is normal.” But upon reflection she realized, “It shouldn’t be normal. That’s what the point of the show is. If it happens again, I will respond differently.”

Another actor in the play, Emily Parker, a junior theatre major concentrating in musical theatre performance, described being on stage with a male scene partner. “A particular group of boys was talking rudely,” she said. They were talking loudly about how they didn’t want to be there and how they thought he [the male actor] was gay. Typical teenage boy stuff. “He’s so gay’.”

Ana Radulescu, a freshman theatre major concentrating in directing, who was the assistant director for the show, watched from the back of the house. She described the behavior of one pocket of students during the same scene that Dagenhardt referred to. “They did call him a ‘fag’,” she said. “He had a line that said ‘No one in high school ever told me I would have a girlfriend,’ and a bunch of people around me just started laughing.” Radulescu also described hearing a student, as a female actor was speaking on stage, speaking only partially in a whisper to those around him, say, “Whore. Bitch.”

Radulescu also said that another student, seated near where she stood at the back, before the show the show had even started, declaimed things like, “It was consensual – I didn’t rape her” and “I did Haven, I promise.” Haven is the online sexual harassment training all students were required to complete.

* * *

Of the five students who spoke on the record for this article, all of them expressed disappointment at the fact that while there were faculty in the theatre during the performance, they were unaware of any efforts by those faculty members to curtail the behavior that continued throughout the show. Several students spoke specifically about the lack of action by the Dean of Students, who they say was seated close to the area that harbored the worst offenders, and couldn’t have possibly missed what was happening. Some students also said that there was less faculty than anticipated, saying that not all of the instructors who were supposed to attend with the students, in order to facilitate subsequent discussion, had been present.

The students who were in the show all expressed, in differing ways, their own indecision about what to do in the face of inappropriate behavior and language. Emily Parker said, “We were in a predicament over whether to confront it or go on with the show.”

Backstage, Rebecca Hougas, a freshman theatre major concentrating in theatre education, was working as assistant stage manager, and said that for much of the play, she wasn’t aware of what was taking place, until late in the show.

“I could hear laughter,” she said, “and I knew this was not a laughing matter.” Hougas said that she really came to understand what was going on by seeing how the actors, who were onstage for most of the performance, reacted when they came offstage. “We had one actor come off the stage in tears over what she was trying to say.”

Several students spoke of actors being physically ill after the performance, and of the company coming together to support one another. Those I spoke with say they were upset upon leaving after the show, even as they had banded together to support one another, but not expecting any significant further fallout from the incident.

* * *

I first learned of what had happened at the performance of It Stops Here when, the next day, playwright and advocate Jacqueline Lawton sent me a Tumblr post recounting the event, written by Nicole Swofford, a recent graduate of Greensboro with a theatre degree who is still close with some of the students involved in the production. It described many of the same incidents that were ultimately described to me, but Swofford was also reporting what was said to her, as she hadn’t been at the show.

Swofford was very clear, and very honest, about her intent is posting, writing:

“Greensboro College is a small private college with less than 2,500 students and there hasn’t been a sexual assaulted recorded in the official report in years. Which is a blatant cover to protect the school from getting into to more hot water than it already is (having suffered from lots of financial problems in the past).

This is disgusting, and as a survivor of my own assault, and an alumni of this school I am appalled. All I can ask is that you share this story with everyone, and realize our fight is far from over.”

She had written on Wednesday evening, and her post, along with Facebook posts and comments about the incident, circulated quickly around the campus.

* * *

Where this story may differ from other accounts of sexual harassment on college campuses is that, less than 24 hours after the performance, the school opened a Title IX investigation. It did so on its own, not as a result of a specific complaint by a student, faculty or staff member. It is quite possible that this was because students reported Greensboro’s Title IX Coordinator, Emily Scott, as having been present at the performance. Her title at the school also includes “Assistant to the President.”

As information was being routed to me, but before I spoke directly with anyone on campus, a statement from the college president, Dr. Lawrence D. Czarda, addressed the issue in a school-wide communication:

“It has been reported that during a special performance Wednesday of the play “It Stops Here” for First Year Seminar classes, several audience members made comments that were offensive and sexual in nature. Under our new Sexual Misconduct policy, the comments that have been reported qualify as sexual harassment. The Title IX Coordinator has reviewed the reported comments and has asked the Title IX Investigator to gather additional information to determine who is responsible for making the comments. The college is pursuing a formal complaint of sexual misconduct against the students and is working to identify them. Upon results of the investigation, those found responsible will face disciplinary consequences.”

He also wrote:

“However, Wednesday’s incident makes clear that we as an academic and social community still have much to learn. That includes all of us, not just a few students. In addition to the Title IX investigation, the college will be reviewing and discussing the entirety of the context of the incident. Among many other questions, we will address such issues as what faculty and staff who were present might have done differently. Beyond meeting our legal obligations, the College’s goal is to make this incident a learning opportunity for the entire College community.”

When I spoke with Dr. Czarda, he volunteered that, “We do not have a history of sexual assaults on campus.” But he said that in response to the national dialogue about sexual violence, “the board adopted new policies which were put into place July 1. All students were required to take an online training course before the process of moving in. In addition, all students are required to do an on-site training program. All faculty and staff were required to do online and in-person training sessions. The fact that the student production is part of the required training means they’ve heard what these issues are about.”

When asked about what kind of preparation students had been given prior to seeing the play, he cited the online and in-person sexual misconduct training implemented by the school. “Did they know specifically what was going to happen on stage?” Dr. Czarda asked rhetorically, suggesting that they didn’t, that students attended the show without any direct contextual preparation prior to attending. But he said, “I think we did a tolerably good job in prepping the students.”

As to why no member of the faculty or staff intervened in light of the catcalling, insults and disruptions, Dr. Czarda said that was a “key question.” He said, “On the one hand, I have been told that there was some behavior that was not atypical of freshmen,” but he said, “I have not talked to any faculty or staff who heard the comments being made. I’m very troubled by that.” As to whether all faculty who we supposed to attend had done so, he said, “I hope that is not the case.”

Regarding steps being taken to insure that the incident would not recur, Dr. Czarda said that there would be campus security and faculty at every performance; he attended last night’s show. “We will have a very clear, immediate response,” he stated. “I would be totally disheartened and shocked if anything like this happened again.”

The students told me that they had agreed that if there were incidents at subsequent performances, they would simply pause in place until it ceased; some said they might direct their looks to where the believed the interruptions to have come from. Several, jokingly, invoked the name of Patti LuPone and her cellphone incident of earlier this summer.

Luke Powell subsequently reported that the Thursday evening performance had taken place without incident. “I’ve never seen an audience give a standing ovation so quickly,” he wrote.

* * *

As readers can tell from this account, some students who were a part of It Stops Here took me up on my offer to speak with them, others obviously did not, and I don’t think anyone should infer anything from the fact that I did not hear from some. That is their absolute right.

As readers can tell from this account, some students who were a part of It Stops Here took me up on my offer to speak with them, others obviously did not, and I don’t think anyone should infer anything from the fact that I did not hear from some. That is their absolute right.

Because institutionally, it is so often the case that in the midst of a crisis organizations initially go silent, trying to decide the best course of action, I have to say that Dr. Czarda’s willingness to speak with me within three hours of my request was both surprising and appreciated.

But I now want to say to Dr. Czarda something I didn’t express when I spoke with him, in part because by the time we spoke, he was getting organized to attend last night’s performance and had limited time. I want to say that while he may be technically correct when he says there is no history of sexual assaults on his campus, that does not mean there haven’t been sexual assaults on his campus, only that they have gone unreported, that they are not part of the school’s records.

Statistically, both on campuses and in the population nationally, sexual assault is too widespread to imagine that Greensboro is a unique sanctuary. Students up until now may have been too afraid, may have been too intimidated, may not have seen genuine evidence of support and understanding in the school environment, prompting them to keep silent. If the prevailing attitude is “it doesn’t happen here” and if the new guidelines have been put in place only to comply with general practice and to insulate the school from future liability, not because of a deep understanding of the prevalence of sexual violence, then there is still a great deal more learning to be done, and not just by the students of Greensboro.

The students I spoke with were uniformly appreciative and indeed surprised by the speed with which the school began its investigation. However, several expressed concern that because the perpetrators sat in the dark and were not immediately discovered and taken out, no one will ever be held accountable. Greensboro College is now on the line both in terms of how it addresses this current situation and what it does now that it has learned that its newly implemented policies are clearly insufficient.

I would also be remiss if I didn’t say to Dr. Czarda and the Greensboro faculty that the students are not only concerned about getting through the performances this weekend. While one noted that they feel “more comfortable knowing that some of the faculty is stepping up and doing their job” and that “the regulations are going to make sure this doesn’t get swept under the rug,” there are now students on your campus who are concerned about recriminations and retaliation because they spoke up, because they spoke out. Beyond insuring the performances go forward smoothly, beyond investigating what took place on Wednesday, you now must do everything possible to make certain that all students connected with this production, and indeed all students (and faculty and staff) are safe and secure on your campus, in the days, weeks and months to come.

What happens at Greensboro in the wake of this incident is not simply a campus matter, but one with impact on every college campus, and for every survivor of sexual assault and their families and friends. If this is what happens when sexual assault is portrayed, what will happen if – and indeed, sadly, when – sexual violence occurs? The school has already been made an example. Now it must demonstrate whether it can set one.

* * *

When asked whether they thought that the rest of the audience at Wednesday’s performance had gotten the message of the show, several of the students professed somewhat ruefully that they didn’t know; one said she knew of one student who had expressly communicated how important it had been for her. If the remaining three performances go as well as last night’s did, then hopefully the message of the play will be reaching many more members of the Greensboro College community in the way it was intended to do.

At the conclusion of our conversation, Ana Radulescu summed up so much of what is essential now in regards to Greensboro and It Stops Here.

“We all now understand what those girls who sent us those monologues were talking about. In a way, we were all sexually harassed yesterday and this Title IX report says so. I never knew that through theatre someone could be harassed. Now in six hours, I understand a lot more of what comes out of those girls’ mouths.

“The idea of this piece is to start this conversation. I don’t think we planned on it starting this way. But if you want to look at it, it’s nothing different than what we meant it to do. The fact that it’s not getting ignored is sort of amazing. It has reaffirmed for us that the piece needs to happen, why it needs to happen and why it needs to happen here. If anyone questioned that, well – we have the answer.”

Update, September 5: A local television newscast covered the incident at Greensboro College last night. You can view their report here; the video piece is more complete than the accompanying text.

The title of the play discussed in this post is shown on the poster as “It Stops Here” with a period at the end of Here. The punctuation mark has been omitted from the text for clarity.

I attempted to reach the theatre department chair David Schram and Josephine Hull, assistant professor of acting and voice, but neither replied to my inquiries.

This post will be amended and updated as the situation warrants.

Please note: I afford all people the opportunity for healthy debate in the comments section of all of my blog posts, but I will not condone statements which advocate violence, racism or are in and of themselves verbal attacks. That is in no way an abridgment of anyone’s First Amendment rights; this is my right as the author and manager of this site. I will not exercise the removal of comments indiscriminately, but it is at my sole discretion.

Howard Sherman is the director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School for Performing Arts.

August 22nd, 2015 § § permalink

Les Misérables at Lakeshore Collegiate (Photo by Darren Calabrese for The Globe and Mail)

If you haven’t been reading Toronto’s The Globe and Mail every weekend this summer, then you likely haven’t come across J. Kelly Nestruck’s terrific series in which he followed a single high school theatre production of a non-musical adaptation of Les Misérables from start to finish.

It no doubt benefited the youthful-looking Nestruck that he would stand out vastly less among a gaggle of high schoolers than say, me, and it appears to have allowed him unfettered access to the process, the logistics and the emotions that are part of any theatrical production, let alone one in a high school. While Kelly wasn’t undercover at Lakeshore Collegiate Institute, I like to imagine his series as the journalistic equivalent of Cameron Crowe’s original book Fast Times at Ridgemont High, but one set entirely in the drama group.

Because I write so often about crises and conflict in high school theatre, I found Kelly’s series essential, not solely because of one part’s focus on what is “appropriate” for a high school production. It is in my memory the most sustained piece of major mainstream newspaper reporting on high school theatre since Jesse Green wrote about the field for The New York Times in “The Supersizing of the School Play” back in 2005. But Nestruck’s series goes vastly farther than Green’s article in its depth.

Since I am not given to aggregating content, I’d prefer to think of what follows merely as an index, with excerpts that in no way give a full sense of the range of the complete articles and the stories they tell, in the hope that you’ll use this post as a guide to the Globe and Mail’s entire series. (The headline of each section will take you to each separate article.) I think for anyone who cares about theatre – not just high school theatre, but the entire field and it’s future – it’s a must-read.

It’s also my way of asking Kelly to take a bow.

* * *

Part 1: A quest to re-discover the magic of theatre, starting in a high-school drama studio

Last fall, approaching my seventh anniversary at the newspaper, I was in crisis about the art form that I had loved since I, myself, was a teenager.

Watching plays at Stratford, or in Toronto, or in Calgary upwards of 200 times a year, I had begun to worry about what I was seeing in the seats around me and on the stages in front of me.

I worried I was writing about an art form still dominated by white directors and playwrights and performers in a country that increasingly was not.

I worried that theatre was becoming an elitist art form whose major institutions were increasingly out of reach of even the middle class, that the core theatre audience was staying white and getting older – and that my profession was swiftly becoming as idiosyncratic and outdated as a mechanic for penny farthings.

Most worrisome of all: I began to lose faith that theatre was worth fighting for. I wondered if the “magic” I had always ascribed to live performance just was a myth I had bought into, and whether more complex and better-told stories – ones that reflect and engage with and interrogate the country and the world we live in – could actually be found on Netflix for a fraction of the cost.

Part 2: Finding a role that fits, on stage and in life

Drama teacher Greg Danakas settles behind a small desk, while 25 students from Grade 10 to 12 gather around him in a circle on the floor. “Let’s read this frikkin’ play!” he says – and you’d never guess the Tim Hortons coffee in front of him was decaffeinated.

“Is anyone Instagramming this?” asks Bradley Plesa, the Grade 12 student who will be playing prisoner-on-the-run Jean Valjean.

Listening to these kids immerse themselves in their characters for the first time, it’s clear how much work – and learning – is ahead of them.

The students pause every page or so as Mr. Danakas defines words such as “cleric” or “consumption” or explains a historical event referenced in the play, like the July Revolution. “It’s a French revolution, not the French Revolution,” Mr. D says – a recurring refrain for the rest of rehearsals.

It’s also clear, however, that Lakeshore’s acting students are up for the challenge. (Unlike me – I reluctantly declined Mr. Danakas’s kind offer to play author Victor Hugo in his dystopian production of the play.)

Part 3: Student actors learn the art of paying your dues

It’s easier for some students at Lakeshore Drama to pay dues than others. Lakeshore, a high school located in south Etobicoke, is not only representative of Toronto’s cultural diversity – but also the city’s economic diversity.

Allan Easton, the school’s new principal, explained the catchment area to me one day over a surprisingly delicious lunch prepared by the culinary-arts students. In the 1980s, Lakeshore was formed by the amalgamation of three schools – an academic-oriented school in a higher-income area, a technical school in a more blue-collar neighbourhood and a third in the centre that was what Mr. Easton calls a “classic public school catering to whoever.”

The demographics of the school still reflect that mix: There are students who live near the water and come from families with incomes that may be significantly six figures, and there are students who live to the east in Toronto public housing. That class disparity is often apparent in the Les Misérables cast – one student contributes to discussions of the play by talking about what she learned on a trip to France, while another shares his experiences growing up in foster care like Cosette.

Many have part-time jobs they struggle to balance with rehearsals – but that hold different importance from person to person. Certain students are saving up to go to expensive universities abroad; others are earning money to help out at home.

Part 4: Censor and sensibility: What’s appropriate for a middle-school matinee?

Mr. Danakas’s most popular production to date was a stage adaptation of Dracula inspired by the 1998 Wesley Snipes movie Blade. It featured 17 vampires who were – in Mr. D’s words – “dressed like prostitutes,” watching the action unfold from scaffolding.

Dracula sold out Lakeshore’s 600-seat auditorium all three nights it played in 2005 – and Kathleen McCabe, the principal then, wrote Mr. D to praise him.

“I am sure that producing a high school play may have limited your true creativity because of the censoring that I imposed on you,” she wrote in the letter, which Mr. D has framed and hung on his office wall. “However, you were able to design an amazing play and keep it on the edge.”

Times have changed, however – and now it’s Mr. Danakas who has to censor himself. “I wouldn’t be able to do Dracula now,” he says with a sigh.

The drama teacher is continuing to deal with fallout from his relatively tame, gender-bending Three Musketeers from last year.

Mr. Danakas had d’Artagnan – who wants to join the Musketeers – played by a female student and decided to deal with the implications of dropping a woman into the jocular world of 17th-century French swordsmen.

Athos, Portho and Artemis gradually gained respect for d’Artagnan, but they behaved chauvinistically toward her in the early scenes. “I thought it was totally harmless, juvenile silliness,” Mr. D says.

That’s not what a couple of local middle-school teachers thought of the groping and crude gestures with épées, however. They pulled their classes out of a matinee due to the sexual slapstick.

Part 5: Set up to fail? Less drama in schools could hurt theatre industry

As opening night of Les Misérables gets closer and closer, more and more people become involved beyond Mr. Danakas’s Acting Class – and more and more elements move outside of his direct control. Cosmetology students are working on the hair and make-up; business students are planning front-of-house operations; and the after-school sewing club is making long, black skirts for all the young women to wear in Mr. D’s non-musical, dystopian take on Victor Hugo’s classic tale.

On top of that, Timothy O’Hare, Lakeshore’s shop teacher, runs an entire for-credit class devoted to the design and construction of the set. I pop by the Toronto high school one morning in early May to see them at work. Instead, I find a handful of students studying or on their phones under the supervision of a substitute teacher, while a documentary about the history of sneakers plays unwatched.

Mr. O’Hare – who is much-loved by his students and doesn’t seem to mind his nickname “Mr. No Hair” – is away with much of the class at the Ontario Technological Skills Competitions. Grade 11 students Lamisa Hasan, Nicholas Latincic and Shamar Shepherd – who all had to stay behind for various reasons – happily leave the doc behind to talk to me about how they collectively designed and built the Les Misérables set.

Part 6: Tale of the red tape: Even in high school, bureaucracy can frustrate art

Allan Easton, the patient and good-humoured new principal at Lakeshore, walks me through some of what is holding up Mr. Danakas’s production. The worry about the fog machine is that it will set off the smoke detectors. The detectors could be bypassed, but then staff would have to be paid to walk around and look for fires – $1,200 in overtime for three nights.

Painting the floor, meanwhile, could be a problem because it might impinge on the skilled trades. “I can’t ever be seen to be taking a union job away from anybody,” Easton explains.

Health and safety concerns also complicate Les Misérables. I remember climbing up on ladders to help hang and focus the lights in my high school auditorium, but Lakeshore’s 1950s-built catwalks are off-limits to all (teachers aren’t even supposed to get up on a ladder, so an adult volunteer did that work on borrowed scaffolding). “Even our caretakers have to have ladder training before they can use a ladder safely,” Easton says. “We’re a very litigious society now.”

As for budgeting, Mr. Danakas used to roughly estimate his ticket revenue, but now sales have to be carefully projected. “ ‘It should be fine,’ isn’t something I can go with any more,” Easton says, with a sympathetic shrug. “Accountability is huge – more than it was in the past. … Taxpayers’ money, right?”

Part 7: Masters of the house: The payoff that makes the gruelling weeks of drama worthwhile

Even at Les Misérables though, it’s clear different audience members want different things. There’s Caroline Buchanan, for instance, described to me as the ultimate drama mom. Not only is her daughter, Samantha Dodds, playing Madame Thénardier, but her partner, Jim Ellis – a 60-year-old management consultant and part-time voice-over artist – has been conscripted to play the role of Victor Hugo.

Ms. Buchanan was one of the first in line to make sure she got good seats – and was primed for a moving experience. “I don’t know why, but it’s very emotional for me,” she says. “There’s so much lead-up – and you see what they all go through. And now it’s here.”

Sara and Alexander Plesa, Bradley and Samantha’s parents, are more skeptical about theatre in general. “I’ll be completely honest, where I’m not the ‘drama mom’ is that school comes first, grades come first and this comes last,” says Ms. Plesa, who works in a civilian role for the Toronto Police and affectionately calls her kids “drama brats.” “I’ll fight with Bradley to the end of time on that – and Mr. Danakas.”

But the Plesas have had a number of personal setbacks over the past year, with Mr. Plesa’s cancer diagnosis, cruelly, coming just as he was on the verge of being hired by the police. Their children’s performances tonight have surprised them – particularly boisterous Bradley’s deeply centred Jean Valjean.

“You wouldn’t know that their life has been the way it has been [lately] by watching that,” Ms. Plesa says. “It’s almost flooring to me: Is that my son?”

Part 8: Exit stage left: Lakeshore Collegiate’s drama students take a final bow

I came to Lakeshore with a naive point of view. I really did want to renew my faith in theatre after becoming frustrated with professional theatre in this country – and rediscover the joy of theatre I had felt as a high school student myself. But you only get to be a teenager once. And what I found when I looked at high school drama through an adult critic’s eyes were things I hadn’t noticed the first time around. I found an acting class that wasn’t fully representative of the racial diversity of its school, and that it was easier for students from certain economic classes to participate than it was for others.

I found a high school theatre with less money and less audience than it used to have, and more hoops to jump through, set up by administrators and unions. I found bureaucracy and I found self-censorship – and I found art’s value being sold with the language of business.

But what I ultimately discovered at Lakeshore is that the dissatisfaction that I’ve been feeling about the professional Canadian theatre I cover as a critic isn’t really about theatre at all, but about the wider society that theatre exists in and reflects. If theatre and democracy have indeed been linked since ancient Greece, then it makes sense that theatre would suffer from the same problems as our democracy – which is also unfair and bureaucratic and filled with leaders who speak to taxpayers instead of citizens.

* * *

Again, bravo to everyone – the teachers, the students, the administrators, the parents and the reporter. Bravo.

All excerpts from the series High School Drama by J. Kelly Nestruck from The Globe and Mail, originally appearing between July 3 and August 21, 2015.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Performing Arts.

August 3rd, 2015 § § permalink

A close facsimile of the Smith Corona typewriter I used for over a decade.

Last weekend, I shared a story and wrote a blog post about Dylan Lawrence, a 13-year-old in Lincoln, Nebraska who staged what appeared to be a fairly impressive production of Shrek The Musical in a neighbor’s backyard. The story seemed to touch an awful lot of people, perhaps because they responded as I had, when introducing the article on Facebook.

Sometimes, those of us who work in the theatre need a quick reminder of the impulse that got us started, which can get lost amid the realities of having made the thing we love into our job. That’s why I think this story is so terrific, because, in one way or another, wherever we grew up or however we got started, to paraphrase Lin-Manuel’s Tony acceptance rap, we were that kid. Let’s share this – let’s make Dylan Lawrence a star, for every kid out there making theatre in a backyard, a basement, or on Broadway.

Frankly, I found myself jealous of Dylan’s energy and initiative, wishing I had been that creative and entrepreneurial at his age, to the degree one can be jealous of someone today over one’s own perceived deficiencies 40 years in the past.

A few days later, I happened on a news story from the UK, announcing that a small London pub theatre would be producing the world premiere of a play by Arthur Miller. Impressed by such a discovery, I read on, only to learn that the unstaged play in question had been written by Miller as a 20-year-old college sophomore. Frankly, while Miller’s reputation is secure, I had to wonder whether the play in question would add to the Miller canon, if it would contradict some aspect of it (a la Go Tell A Watchman), or would it simply be a novelty that goes back into the Miller archives after this run.

These two incidents began to work on me, as did a flip comment I made, entirely in jest, to a Twitter commenter about the Miller story. I said something to the effect that I doubted if anyone wanted to read my unproduced plays.

Shortly thereafter, it hit me. I actually have some unproduced plays. Or at least I had them. I’m not digging through old files and boxes for them, for me or anyone else, and I’m really hoping that no one else has copies. But I am willing to share with you what I recall of my efforts, which I haven’t thought about in quite some time.

It’s worth noting that I saw very little theatre as a child. I attended a children’s theatre show at Long Wharf Theatre in 1967 for the fifth birthday of a kindergarten classmate, of which I remember nothing but the seeming vast darkness of that actually intimate space. In second grade, my parents took my brother and me to see the national tour of Fiddler on the Roof at the Shubert Theatre in New Haven, and what I remember most is “Tevye’s Dream.” It stands out not because I liked the number, but because as a child I was very skittish about anything supernatural, and so my parents had spent a lot of time preparing me for the appearance of Frumah Sarah. The anticipation was so significant, and the event so anticlimactic, that it was my greatest takeaway. My first Broadway show, circa 1975, was Stephen Schwartz’s The Magic Show. My second was Beatlemania.

Despite a paucity of real world examples, I conceived of a passion for theatre, and my parents enrolled me in a Saturday morning drama program at the New Haven YMCA. I believe I was in fourth grade. I dimly recall the space in which we worked, that there were only a few other kids involved, perhaps three or four, and I have no memory of the class leader. But I do remember that the program concluded with some manner of performance – I don’t even recall any audience – of the play I wrote for the group, Love and Hate. The plot? No idea. But remarkably, I do think that even then I was aware of a book called War and Peace, and that it sounded pretty good, so I mimicked the wide scope of its title. I suspect I performed in Love and Hate as well, but that aspect is too indistinct. My older brother wouldn’t have attended out of disinterest, so I can’t ask him about it, and my sister would have been to young to sit through it. With my parents gone, these threads are all that is left of Love and Hate.

My next writing efforts, some time during fifth and sixth grade, were both done under the tutelage of my synagogue’s cantor, one Solomon Epstein, who was a young Jewish man from the south whose lasting gifts to me included several of my formative cultural experiences, notably my first art museum visits, as well as my lingering tendency, despite my New England upbringing, to say “y’all.”

It was Cantor Epstein who had our second grade Hebrew school class sing a short pop cantata called Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, years before it was expanded into a stage show (I managed to tell Lord Lloyd Webber this story years later). He staged several similar, but longer, works as multimedia events on the synagogue’s stage – after all, this was the early 70s. I remember learning how to synchronize three sets of dual slide projectors with a big electrical box called a crossfader, and asking him whether the rabbi would permit him to have an attractive young woman of 17 or 18 years of age dance in the synagogue in a body suit (it was fine, apparently).

But he also encouraged me to write, going so far as to loan me a portable Smith Corona electric typewriter, which was so much easier than the vintage manual typewriter that dated from my parents’ school days, and probably before; they later bought me my own electric, the same model as the one I’d borrowed. First, I undertook to do my own adaptation of the Peanuts comics for the stage (an avowed fan of the strip and quite aware of You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown). I did little more than transcribe the various cartoons from the comics, which I had been cutting from the newspaper and pasting into scrapbooks for years, and arrange them in short scenes. My only innovation, not entirely surprising given my guide, was to invent a new character, a Jewish “Peanut” named “Tsvi,” which not so coincidentally is my Hebrew name. The title of this opus: Happiness is a Jewish Peanut. Clearly at that time I was seeking my cultural identity by placing myself among characters I loved.

Subsequently, I tackled a more significant project, adapting a novel, the name of which escapes me now. It was a wry Jewish fantasy about the lives of babies in heaven before they’re born and sent to earth, but it actually had a narrative, which ended with its main character being launched to meet its parents. I recall that in the book’s mythology, the philtrum, or “drip canal,” under our nose is where God snapped his fingers against us to bring us to mortal life send us to earth. Funny what stays with us, no? Again, I was probably transcribing more than writing, but as this was a several hundred page novel, I did have to assert some basic editing skills, if nothing else.

My last writing attempt never got beyond the outline phase, but it was a special high school project that proved too overwhelming. Looking back, it was utterly self-indulgent and also self-revelatory, a play in which I imagined a version of myself, to be played by me. This main character, a high school student in a school much like mine, was to look at the talents of other students I –I mean he – admired and then, in turn, he/I would demonstrate those very same talents, at least on a par with, if not better than, those I envied. It would have been great fodder for a therapist, but as drama, no doubt quite inert, albeit a showcase for whatever talents I actually had.

To be honest, I still have ideas for plays, and screenplays, from time to time, some of which have been turned over and over in my head for many years as the circumstances of the world, or of my life, have changed. I honestly believe one or two of them are pretty good, but I have found that my impulse to write is best served by the essay form, the blog form, because it allows me to pursue a single idea in a single writing session. It is the commitment of returning to the same story, over and over, day after day, tweaking, adjusting, and fixing endlessly that has staved off any real creative efforts. It is why I admire playwrights (and screenwriters, and novelists) so very much.

I unearth all of this now because of young Arthur Miller decades ago, because of young Dylan Lawrence today, and because of the countless youthful creative artists who may not yet realize that’s where they’re headed, who may not have the support and access that Dylan Lawrence, Arthur Miller and I all had. We know what happened with Miller, and I plan to follow and support Dylan in any way I can – as I will do as much as I’m able for any young person inspired by the arts, especially theatre, and I hope that holds true for those who read my blog.

As for me, I came to understand that I am not a dramatic storyteller, but an avid consumer of stories, who wants nothing more than to play some role in their getting told, and in supporting and knowing those who tell them. Just as there are undoubtedly countless young artists and administrators – and audiences – to be nurtured, I hope there are at least as many parents, mentors and teachers to pave the way, declining budgets and skittish authority figures be damned.

And check back with me in about 20 years. Maybe by then I’ll have enough material for a marginally entertaining one-man show. You never know.

July 26th, 2015 § § permalink

Sundays tend to be slow days for theatre news, if you get most of your theatre news online. By the time I sit down to trawl through “the Sunday papers” for theatre stories to share, primarily through my Twitter account, I’ve seen most of what’s on offer already. The New York Times Arts stories start filtering out through Twitter and Facebook as early as Wednesday, the Sunday column of Chris Jones at The Chicago Tribune is usually available by Friday afternoon, and so on.

Sundays tend to be slow days for theatre news, if you get most of your theatre news online. By the time I sit down to trawl through “the Sunday papers” for theatre stories to share, primarily through my Twitter account, I’ve seen most of what’s on offer already. The New York Times Arts stories start filtering out through Twitter and Facebook as early as Wednesday, the Sunday column of Chris Jones at The Chicago Tribune is usually available by Friday afternoon, and so on.

I look at my theatre news curation on Sundays as perfunctory (just as Saturdays tend to be particularly busy), knowing I’m unlikely to find much, which is why a story in the Lincoln, Nebraska Journal Star managed to catch my eye. It’s not, so far as I can tell, in the paper’s arts or entertainment section, but in local news, the sort of charming slice of life that columnists look for to illuminate their communities. However reporter Conor Dunn found out about impresario Dylan Lawrence’s production of Shrek: The Musical in a neighbor’s backyard, I’m awfully glad it came to the paper’s attention, and that I stumbled upon it. If you haven’t seen it yet, here’s a taste:

Now 13, Dylan pulled off his first major production this weekend — “Shrek: The Musical” — at The Backyard Theatre in southeast Lincoln, a venue literally carved out of a family’s backyard and completely run by kids.

This isn’t the first time Dylan has directed a play, however. It’s just in a new location. Last summer, he and 10 of his friends performed “The Wizard of Oz” in his Lincoln backyard. Dylan said the cast put the show together in just nine days and about 70 people attended.

* * *

While most theatrical productions have a set and a stage crew, Dylan took most of the roles on himself, alongside directing and performing as Lord Farquaad in the show.

He’s sewn the costumes, designed the props, rented a sound system and also created light cues using a software program on his laptop. He even created The Backyard Theatre’s website.

I have no doubt that there are other Dylan Lawrences out there, so I like to look at this story not as a wholly unique incident, but rather as emblematic of the grassroots love of theatre that inspires kids, and that in turn can inspire even those of us working at it professionally. I’m glad it’s finding resonance online – my post has been “liked” on Facebook 72 times in less than two hours and shared 37 times, including by David Lindsay-Abaire, who wrote the show’s book and lyrics. I suspect the number will climb much higher, because I believe that many more people will connect to it in the same way that I did.

I have no doubt that there are other Dylan Lawrences out there, so I like to look at this story not as a wholly unique incident, but rather as emblematic of the grassroots love of theatre that inspires kids, and that in turn can inspire even those of us working at it professionally. I’m glad it’s finding resonance online – my post has been “liked” on Facebook 72 times in less than two hours and shared 37 times, including by David Lindsay-Abaire, who wrote the show’s book and lyrics. I suspect the number will climb much higher, because I believe that many more people will connect to it in the same way that I did.

There was one comment posted to me on Twitter, where I also shared the Journal Star story, saying “Hope he has the rights.” While I am adamant that authors should be compensated for their work, I wonder whether this ad hoc production by children 14 and under, with no institutional backing or adult leadership, reaches the level at which a license is required, and I intend to find out. However, if it turns out that a license should be paid, I don’t want my decision to share a local story that might have otherwise gone unnoticed to be visited upon Dylan and his company; consequently, I’ll pay for any rights required myself, to help Dylan practice what I preach, because it’s a small price to pay for encouraging the love of theatre and for a tale that reminds so many of us why we got into this crazy and thrilling business in the first place.

I performed on stage for the very first time as Charlie Brown at my day camp’s condensation of You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown into about 20 minutes. I’m willing to bet it was unauthorized and unlicensed, and I don’t say that to encourage scofflaws, but merely as a fact. While it sounds like The Backyard Players of Lincoln, Nebraska are considerably more sophisticated than the rudimentary theatrics at Camp Jolly circa 1969, I feel a kinship to Dylan, even though he is obviously significantly more enterprising than I was. So I urge you to read his story and, perhaps, remember that very first time you made a stage in your backyard or your basement, or sang a show tune in elementary school before you’d even seen a play. Because we all started somewhere, and we need to always celebrate those taking their first theatrical steps whenever the opportunity presents itself.

Update, July 27, 7 a.m.: 18 hours after I first shared the Journal Star story via Facebook, my posting has been liked 107 times and shared 81 times. I have no way of knowing how it spread beyond there, but the original story on the Journal Star website has been “Facebook recommended” over 2700 times. We are that kid.

May 4th, 2015 § § permalink

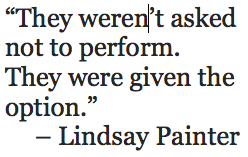

When it was all said and done, three student-written short plays, part of an evening of playlets, monologues and songs, went on as scheduled at Cherokee Trail High School in Aurora, Colorado. But in the 10 days leading up to that performance, the students claim they were told the plays and one student-written monologue were canceled. The students successfully garnered the attention of a local TV station, the National Coalition Against Censorship, and the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama over the impending cancelation.

However, the school claimed the shows were never canceled and that the students misunderstood, but first delayed the performance of the pieces in question and then rescinded that delay, which would have pushed the plays to a later date. The school cited lack of proper process for approval, issued permission slips to the parents of all participating students and sent a broader memo to parents regarding the content of the pieces, defining them as “suitable for mature audiences.” Amidst this, rumors suggested that some contemporaneous school vandalism was the work of the drama kids. One student-written monologue was canceled entirely because the student’s parents reportedly denied approval for it to be performed.

What precisely triggered all of this activity around brief student-written plays? LGBTQ subject matter.

* * * *

The cast and creators of “Evolution” at Cherokee Trail High School

Students in Cherokee Trail’s Theatre 3 class developed the “Evolution” evening under the banner of their student-run Raw Works Studio, working on them both in class and after school for more than a month. According Theatre 3/Raw Works students – including Josette Axne, Kenzie Boyd, Brandon McEachern, Dyllan Moran, and Ayla Sullivan, with whom I shared phone calls, texts and e-mails at various times beginning April 16 – they were informed by the school’s Activities Director Christine Jones on April 15 that because of the LGBTQ content in the student written works, the pieces could not be performed and would be excised from the pending performance set for April 24.

The students immediately took action, reaching out to the local media, setting up a Facebook page called “Not Original,” contacting the National Coalition Against Censorship (which in turn contacted the Arts Integrity Initiative), all over their understanding that the plays were being cut from the performance. After first speaking with Axne, I spoke and corresponded primarily with Sullivan in the first few days.

By the time Channel 9 in Denver, NCAC and Arts Integrity made contact with the school’s administration on April 16, Principal Kim Rauh had prepared a response, which portrayed the situation in a different light. It read, in part:

The student written plays will be performed at Cherokee Trail High School. The decision that was made was to postpone the date of the performance to allow our theater process to be completed. Students were invited to meet with us to work through the process and give the necessary time to work through all of the “what ifs” and attempt to be proactive as opposed to reactive and to plan for success. With every production there is an element of both directorial and administrative review and approval. The plays were submitted after the due date for final approval for the original performance date. We have extended the process timeline to allow the plays to be performed at a later date at Cherokee Trail High School.

Channel 9’s account of the situation, the only significant local news story, was reported on the evening news on April 16, stating that the pieces would now be performed on May 9.

* * * *

“Not Original”’s Facebook post about school vandalism

On Friday morning April 17, shortly before 8 am Colorado time, I received, in the space of ten minutes, an e-mail and phone call from Ayla Sullivan. She was deeply concerned that an act of vandalism at the school overnight was being attributed to the Theatre 3 students, even though she said it had been covered up before students arrived at the school that morning, so that not only were she and her classmates not involved, they didn’t even know the nature of the vandalism. Sullivan asked how the drama students should address this, and I advised them to tell the truth and make clear their position about whatever had occurred. Ten minutes later, the following message was posted, as a screenshot from a cellphone, to the “Not Original” Facebook page:

The vandalism we are now aware of that happened earlier this morning was not done by any member of Raw Works Studio and is not affiliated with the Not Original Movement whatsoever. Due to none of the members even seeing this vandalism, we do not know what it says and if it is even related to us. Whatever the markings say, we can not see it because it was covered as early as 6:45 this morning.

If someone wrote something that is related to Not Original through vandalizing public property, we absolutely oppose it. We do not support vandalism, violence, or hate speech. We do not support this action. We are, and have always been, a peaceful movement.

This is not the way towards change. This is not acceptable.

To date, the students say they haven’t heard anything more about the vandalism. It was a brief source of anxiety, but not central to the dispute.

* * * *

On April 17, I sent a series of questions about the events of the past two days to Principal Rauh, copying Tustin Amole, the director of communications for the school district. It was Amole who responded, very promptly. Describing the reasons and process for what was happening with the plays, she explained:

All student performances are subject to administrative review prior to rehearsals beginning. The teacher is responsible for submitting material for consideration. I do not know how soon prior to that the students finished the plays. Regardless of when the materials are submitted, there is a long-standing process which must be followed.

In cases where the material may be mature or sensitive, the school meets with the parents of the students involved to make sure that they have permission to participate. We would then inform the broader community so that they are aware of the subject matter and can make a decision about whether they want to come and perhaps bring younger children.

Because I had pointed out that the new date set for the student written works (all of the other pieces were to be performed as originally scheduled) conflicted with tests for Advanced Placement and the International Baccalaureate, Amole wrote me:

In our effort to ensure that the students have the opportunity to perform the plays, we selected a date that allowed time for the process. We understand concerns about the timing, but this is the only available opportunity before school ends.

Following this exchange, I wrote again to Amole, inquiring as to the school’s specific concerns about the material, which had gone unmentioned. She replied:

The plays concern some issues around sexuality and gender identity. We would not censor the subject matter, but do work to ensure that all parents were informed and give consent for participation, and that attendees know the nature of the material. In other words you would not take children to a movie without knowing what it is about, nor are you likely to allow children to participate in an unknown activity. In the Cherry Creek School District, parents are given the option of reviewing activities, books and other materials and asking for alternatives if they object to what is assigned.

As for when the review process had begun, she responded:

The conversations with the students began when the material was submitted to administrators for review. We were looking for alternative dates to complete the review process when some of the students decided to call the media. Because they did not have that class yesterday, they were unaware that a new date had been determined. Had they waited to talk to their teacher during the next class, they would have been informed. They also always have the option of coming to the principal to express their concerns and they chose to call the news media instead. We regret that they chose not to work through our long established process.

That same day, the students told me, there were two meetings with Christine Jones, who outlined for them the plans for going forward.

* * * *

After all of this, imagine my surprise when, just before 5 pm Colorado time on Monday, April 20, the NCAC and Arts Integrity Initiative received the following e-mail from Ayla Sullivan:

We have officially gotten our show back! Thank you so much for your help and support. Your belief in us is the only reason we have this. Thank you.

I wrote Rauh and Amole minutes later, to find out how the timetable had been restored to the original date. Amole replied two days later, sharing the communication that was going out to parents that day, which read in part:

I wanted to take this opportunity to communicate an update regarding the Theatre 3 production at Cherokee Trail High School, Evolution. Evolution contains a series of vignettes including songs, original student works and published scenes centered around the theme of love, some of which contain topics that may be considered best suited for mature audiences.

Because we are not putting topics on the stage, but rather actual students with actual feelings it was our desire to ensure that we had the time to adequately communicate the nature of the production with our parents and community members to help ensure the safety and well-being of all involved. The events of the past week have allowed us to do so and as such the administration, director and students have determined that we can perform the show on the originally scheduled date of April 24.

In response specifically to me, Amole added:

As of now, we do not have permission from all of the students’ parents to participate. While we continue to work to obtain the required permissions, we will honor the parent’s wishes, as per district policy. The performances of those students who do have parent permission will go forward.

* * * *

Graphic design for “Evolution” at Cherokee Trail High School

On April 24, the following student written pieces were performed as part of “Evolution”: A Tale of Three Kisses by Kenzie Boyd and Brandon McEachern , Roots by Dyllan Moran, and Family: The Art of Residence by Ayla Sullivan and Brandon McEachern. The evening was, in the words of Dylan Moran, in an interview with KGNU Radio that he gave the day of the performance, about “how love evolves, both through time and within ourselves.”

On April 29, five days after the performance, I spoke with the students to ascertain how the performance had gone. They reported attendance in the neighborhood of 300 people, which while it only filled the orchestra section of their theatre, they said was comparable with other performances of this kind, and they seemed satisfied with the turnout. But had there been, when it was all said and done, any censorship of the work?