He clasps his hands together and bows, low. When he lifts his head again, his arms now at his sides, his eyes glisten, moist perhaps, but not teary. He lifts his gaze to the balcony, scans it, then looks to those seated closest to him. As he glances across the front rows, there is the very slightest hint of a warm smile, perhaps conspiratorial. Then he joins hands with the rest of the company.

He clasps his hands together and bows, low. When he lifts his head again, his arms now at his sides, his eyes glisten, moist perhaps, but not teary. He lifts his gaze to the balcony, scans it, then looks to those seated closest to him. As he glances across the front rows, there is the very slightest hint of a warm smile, perhaps conspiratorial. Then he joins hands with the rest of the company.

“Look, he’s so moved,” I’ll overhear a nearby lady remark. “Oh, but now he’s smiling,” says another, relived and happy, bonding with him in the very final moments of several hours in the theatre. They feel more connected because he’s shown them all that he feels so deeply, sad, elated, a bit tired, by all that’s come before.

I have seen this particular bow more than once, and it never fails to move audiences to comment, no matter what has come before. Because it is the bow of a friend who typically plays leading roles, I have seen it at the end of classics and new plays, of comedies and dramas. It is a performance unto itself, but no less genuine for being one. And while the play that preceded it may be flawed, this particular, brief display of emotion and thanks always delivers.

We say so much about the theatre we see that we often don’t take into account the curtain call itself, the bows, the epilogue to the performance that allows us to join with the company one last time. Indeed it is not uncommon at the end of a curtain call for the actors, before they depart the stage, to reach out their hands, stretching towards us, to applaud us, in mutual admiration, cementing a bond. Nowadays, when the curtain call is discussed at all, it is to decry the falseness of Broadway’s seemingly de rigueur standing ovations, an honor once reserved for performances of extraordinary merit, now the inexplicable and meaningless standard.

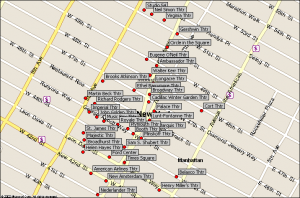

Let’s not engage in yet another debate about the devalued ovation, but consider instead the act of the bows. Even at their simplest, different stages dictate different patterns; while a proscenium allows for a straightforward, straight-across line of actors entering and bowing successively, in the order of the size of their role or, in some cases, their personal fame, looking out, looking up (if there is one or more balcony) joining hands and bowing en masse. If the stage is a thrust, or perhaps in the round, the company is usually arrayed separately, and they turn together to each side of the audience as they bow, keying off of some unseen signal in a final bit of subtle choreography.

Subtlety is not always required; the curtain call can be an extension of the performance that enhances it. As if we had not had enough fun at Matthew Warchus’s Boeing-Boeing, he enlisted Kathleen Marshall to choreograph a final burst of motion and mirth, insuring that even the bows failed to begin to distance us from the show we had enjoyed; it sent us bouncing out of the theatre, not merely collecting our things after dutiful or enthusiastic clapping. A number of English musicals offer the mega-mix finale which, after we’ve already begun clapping and perhaps taken to our feet, recaps what’s come before with a medley of the show’s best tunes; it is designed to get us on our feet, often against our better judgment, lest we be seen as spoilsports. In the case of Mamma Mia!, the curtain calls are topped with the song “Waterloo,” a big Abba hit that couldn’t be shoehorned into the plot, and its last minute deployment takes the entire show the one final joyous, rhapsodic plane.

Productions of the vintage Arsenic and Old Lace are known to have a series of complete strangers emerge from the set’s supposed basement; they are nightly-rotated strangers who are recognized as some of the heretofore unseen corpses sent off by the sweet old ladies’ wine. At Bring It On, the curtain calls are accompanied by videos of the cast in rehearsals, as well as the creative team; while it mirrors the videos that pervade our internet lives, or the bloopers that run alongside credits in some movies, it shows that the cast is “just like us.” It also allows brief glimpses of the creative team as we applaud and while they may not be known to all, I could smile as I applauded, at Amanda, at Lin-Manuel, at Tom and so on; I have always been of the belief that authors, directors and designers should be brought to the stage for bows whenever they are in the house, not only on opening nights, and this is a compromise solution.

These examples among the most creative I’ve seen, and perhaps far too rare. They don’t belong in serious drama, of course; they’d be ridiculous at Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? or The Normal Heart, but something special is certainly appropriate for vintage musicals and for comedies, even classic ones. Sadly, bows are too often an afterthought, roughly staged if at all at the first previews, given order as the production comes closer to an opening night. That is why I always marvel at my friend’s self-contained bow; no matter what the circumstance of a given production, he is complete unto himself at the denouement, with unwavering results.

Of course even the most perfunctory bow is better than none at all. Some directors, typically on dark works with many deaths, will argue that to bring the actors back to the stage is to deny what has come before; to brings back corpses (apparently having never seen Arsenic and Old Lace) makes no sense. In two productions that I have seen – the most recent Broadway revival of Journey’s End and, years earlier, Mark Lamos’ Julius Caesar at Hartford Stage – the bodies strewn about the stage rose before our eyes, not under cover of darkness, and we applauded as were slightly chilled, never knowing whether we’d just applauded performance, staging or resurrection, not that it matters.

I take issue with directors who eschew curtain calls on artistic grounds, because, along with everyone else in the audience, I am denied the opportunity to express my appreciation to the cast, and we leave the theatre dissatisfied and puzzled by the absence of convention, surely not what any director really seeks. Applauding is a theatrical social contract of many, many years’ practice, and appreciation denied is appreciation diminished.

I’m not suggesting that every production should contrive a unique curtain call; to do so would then make them as boring as standing ovations have largely become. But as we parse every aspect of theatre making and theatre marketing to insure that we are attracting and sustaining audiences, we mustn’t forget the impact of that last minute – after the show itself has ended but before the audience is released to back into the real world – and its ability to enhance what has come before and to make audiences truly a part of it, achieving community not just within the audience but throughout the theatre.