April 10th, 2016 § § permalink

When we last looked in on Ocala, Florida on March 2, the City Council had declined to take any action on the claim by local businessman Brad Dinkins that upcoming performances in city owned sites violated the terms of the venues’ leases. That came after an hour of presentations at a City Council meeting at which the majority of the speakers defended the bookings in question, while only a few voices were raised against them. As a result, a benefit performance of The Vagina Monologues and a burlesque show went on as planned.

Following the meeting, the Ocala Star-Banner quoted Council Chairman Jim Hilty as saying, “We don’t feel (we want) to ban this. We’re definitely not looking to ban anyone’s free speech. I believe at this point we have to allow the shows to go on.” The paper further noted, “In cases where performances were grossly obscene, Gilligan said the city would likely invoke the part of the contract that limits performances.”

A separate editorial in the Star-Banner, titled “A Lesson in Public Discourse,” praised the previous day’s debate. It began, “It was a good day at Tuesday’s Ocala City Council meeting. Not only was a fundamental American principle discussed and debated passionately for more than an hour and left untrampled, but it was done so in a civil manner that our presidential candidates would do well to emulate.”

Katerina Aella in The Vagina Monologues (Photo by Ralph Demilio)

So while it is not entirely surprising that Brad Dinkins remains unsatisfied by the City Council’s action, or rather lack thereof, since none was deemed necessary, it is surprising to find Dinkins garnering headlines on the same subject yet again. He’s now convinced that by standing for the constitutional rights of individuals using city owned property, things are only going to get more “adult” in Ocala.

Dinkins’ prediction: People inclined to produce adult-oriented theater or films are likely to do it again, given the council’s unwillingness to stop last month’s performances of “The Vagina Monologues” at the Reilly Arts Center and a retro burlesque rendition in the Marion Theater. “The way the trend it going it’s very likely (there will be more adult-oriented performances).” (Star-Banner, April 9)

What is remarkable about the extensive new article is that the first 13 paragraphs concern Dinkins’ position exclusively. While many voices are heard from thereafter, explaining why the City Council’s decision was appropriate and legal, the paper has allowed one single person to set the tone for a review of an issue settled a month earlier, at a point when there isn’t even a particular performance or production to debate.

Mr. Dinkins has every right to express his opinion. But why exactly does the Ocala Star-Banner have to give him a platform every time he complains about his worries and fears regarding live performance? Is Dinkins’ Ocala’s own Donald Trump, whose every utterance is worthy of attention, no matter how ill-considered?

If one reads the entire article, “Brad Dinkins still wants City Council to stand against adult shows,” it’s clear that the City Council’s actions in March were made according to local and Constitutional law. Yet now city officials are starting to parrot some of Dinkins’ concerns, and speak of looking for oversight they previously said they didn’t need.

Hilty said it’s possible future performances of adult-oriented films and plays held on publicly owned property could be coming.

“I think it can happen. They could be a little bit more emboldened now,” Hilty told a Star-Banner reporter a few weeks after the March council meeting. “But I would hope they wouldn’t go to that extreme to push the envelope.”

For now, City Attorney Pat Gilligan is reviewing the leases if they should be changed to give the council a stronger hand.

Gilligan said he wants to “give the City Council as much legal flexibility” as possible if it is to grapple over a performance it thinks isn’t compatible with the community’s values. He said the current lease gives the elected officials plenty of authority over what’s performed on city property.

This new hedging towards worry and control is contrary to the message that came out of the City Council meeting. It suggests that Ocala might be looking for legal grounds to censor creative work on city property in violation of the First Amendment. It sends a not-so-tacit message to the operators of the venues in question that they should be careful about what they present, lest they cross a line that they haven’t even come close to.

Could Brad Dinkins be laying the groundwork for a political campaign based upon his highly subjective stance on public decency? If so, it seems that city officials and the media in Ocala are only too willing to give him a hand in building his base. Admittedly, there can be value in a single voice fighting against a status quo, even when the majority think otherwise. But when that solo voice is given a disproportionate platform in order to try and subvert the Constitutionally-rooted principle of free speech, maybe it’s time for everyone to get a grip and remember: nothing illegal or even subversive has taken place in Ocala, and there’s nothing on the horizon either.

If Mr. Dinkins wants to press his cause, let him do so on a blog, or social media, or by buying ad time or space. Let him call in to talk radio if he wishes and flog his censorious efforts endlessly there. After all, in the words of the Star-Banner editorial:

In the end, the City Council appropriately took no action. And while we are pleased to see another unnecessary civic kerfuffle come to its proper end, we cannot help but be proud of how the community handled this issue — or non-issue, as it turned out.

Recapping: this “unnecessary civic kerfuffle” has come to its “proper end.” It’s a “non-issue.” No censorship. Performances in city venues continue. Move on. No matter what Brad Dinkins thinks.

April 9th, 2016 § § permalink

Online or in print, headlines are meant to be grabbers. Just this week, I was taken aback by, and simply had to read, The Independent’s “Radioactive wild boars rampaging around Fukushima nuclear site.” Honestly – how could I resist? A great headline need not always have a pun, such as the New York Daily News’s declaration against gun violence, “God Isn’t Fixing This.” Of course the classic of the genre is the New York Post’s “Headless Body in Topless Bar.”

Online or in print, headlines are meant to be grabbers. Just this week, I was taken aback by, and simply had to read, The Independent’s “Radioactive wild boars rampaging around Fukushima nuclear site.” Honestly – how could I resist? A great headline need not always have a pun, such as the New York Daily News’s declaration against gun violence, “God Isn’t Fixing This.” Of course the classic of the genre is the New York Post’s “Headless Body in Topless Bar.”

Though I see journalism and criticism discussed and dissected six ways to Sunday in article upon article, blog after blog (and I’m often an avid participant), headlines tend not to be a significant part of the discussion of arts journalism. The “star rating” system gets a lot more attention, as of course do the reviews themselves. But headlines can have an enormous impact on your impression of a review, or a show; like stars, headlines may, for an enormous number of readers, be all they ever learn about a show.

Good headline writing is a talent, a craft, and that holds true in old-line print media or online. The Huffington Post seems to have made its fortune on headlines that promise more than they deliver, harking back to the best of true tabloid journalism, but dammit they make you look. None of us are immune to the lure of shrewd headline.

As someone who surveys the internet daily for news stories of theatrical interest, I marvel at the headlines I see, some clever, some mundane, some inadvertently hilarious. While there are fine editors of all stripes who contribute to headlines (the general public doesn’t realize that in many cases, the writer of the article has no participation in the process), there’s no question that at smaller outlets that still generate a lot of copy, the process of headline writing can become a bit rote. In the most absurd cases, I envision a lone editor, late at night in an empty newsroom, wracking their brain for copy that will fit both the story and the allotted space. I see this editor being responsible for headlines such as “‘Fences’ features all black-cast,” which I saw online two years ago, conveying a bit of information self-evident in 2014 to anyone familiar with August Wilson’s 1987 play.

My imagined editor seems to work on a lot of theatre reviews but apparently doesn’t go to a lot of theatre, and so I muse upon headlines I suspect most of us would not want to see; endless alliteration, bad puns, inadvertently risqué or even offensive juxtapositions pouring from a sleep-deprived mind, one that may have only read the review cursorily. Consequently, here’s a selection of 25 headlines I created for a range of plays and musicals – all to accompany positive reviews, as going negative is too easy – with the hope that it will make its way to arts copy desks across the country as samples of what not to do. But I can assure you that these are very close to the reality I see daily.

- Where’s the beef? Steer yourself to prime AMERICAN BUFFALO

- Don’t paws, run to (litter) box office: CAT on TIN ROOF will have you feline HOT

- Fine end to CORIOLANUS, but you may be bummed out

- Insane fun to be had at nutty CRAZY FOR YOU

- Miller spins tight-knit yarn about SALESMAN’s DEATH

- Piercing EQUUS quiets the neigh-sayers

- No woe at MOE show, so grab FIVE GUYS and go, shmoe

- Kernel of corporal punishment makes LIEUTENANT OF INISHMORE generally great

- LITTLE WHOREHOUSE turns tricks into trade, hooks audiences to happy ending

- Compelling climax in THE ICEMAN COMETH

- You’ll want to preserve JELLY’S LAST JAM

- No need to hope for charity at LEAP OF FAITH

- NIGHT time is the right time for Sondheim’s MUSIC

- Oh, my: THE LYONS is a tiger, bears seeing

- Missed I and II? You’ll still enjoy MADNESS OF GEORGE III

- MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM is tops

- M. BUTTERFLY emerges in unexpected, satisfying ways

- Start spreading the NEWSIES

- NORMAN’s CONQUESTS make him Attila the Fun

- ONE MAN, TWO GUVS: three cheers four you — five stars

- Norris’ PAIN AND THE ITCH receives critical an-ointment

- Local troupe puts impressive PRIVATES ON PARADE

- Current RAISIN IN THE SUN prunes away time’s overgrown vines

- There’s no need to fear, TOPDOG/UNDERDOG is here

- Yes VIRGINIA, Albee’s foxy WOOLF blows the house in

I will close by quoting a long-remembered headline, 100% accurate, that accompanied a glowing review for a show I worked on once upon a time: “Crawl Over Ground Glass to See This Show.” Enticing, huh? Truth can be stranger than fiction.

This is a slightly revised version of a post originally published in 2012, under the dreadful headline, “Much Read Heads Can Put Chorus In Line Or Punch ‘Em Out.” I have no idea what I was thinking. Needless to say, no one read it.

March 1st, 2016 § § permalink

When a student-devised piece of theatre begins as The Politics of Dancing, an examination of relationships springing from Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, and is ultimately produced as This Title Has Been Censored, something is amiss. When a student production scheduled for multiple performances in a college theatre department’s mainstage season ends up as a single workshop performance with rudimentary tech given during a final exam period, something is strange. When an original work of theatre begins to address gender roles and is immediately downsized, something is troubling. When these actions were prompted because an inchoate project was judged by departmental leadership based solely on a few preliminary scenes reviewed four months before the work was to be finished, something seems wrong.

But those are all aspects of what transpired over the past several months in the theatre department of Oklahoma State University. The Politics of Dancing, which had been announced as part of the school’s 2015-16 mainstage season in the Vivia Locke Theatre, which seats some 500 patrons, was to have been presented in February; the rest of the season included A.R. Gurney’s What I Did Last Summer, and The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee. Instead of The Politics of Dancing, the school produced John Cariani’s Almost, Maine.

So what exactly happened to The Politics of Dancing? In October, Professor Jodi Jinks, who holds the school’s Mary Lou Lemon Endowed Professorship for Underrepresented Voices, shared a few short scenes from the work the students had begun to create with the head of the department, which both she and the students say weren’t necessarily representative of what the finished work would be like, given the evolving nature of any devised theatre.

“Professor Jinks allowed us as an ensemble to explore what we wanted. It kind of naturally flowed in that direction,” said student Jessica Smoot via e-mail. “Honestly I think it just came from the fact that you can’t properly explore romantic relationships without understanding gender, and since it is such a hot topic these days it became a much more fascinating subject to explore.”

Student Joshua Arbaugh said, also via e-mail, “The focus of the show never switched from ‘general relationships.’ Gender was only one subject that the show was going to touch on. There was never a time that we as a group decided that the show would be about gender. However, gender and gender roles play a big part in relationships so we devoted a healthy amount of time early in our devising process to explore the many facets of gender in our research and our work. We had no idea that this would displease anyone and did not believe that it was a divergence in our declared ‘focus’.”

Prof. Jinks says that she shared some very early drafts of Dancing on October 19 and two days later department chair Andrew Kimbrough met with the students involved in the production and, in Jinks’s words, “dropped the bomb, or gave the option.”

“We could change the direction we were heading in and create something for our [mainstage] audience, or the students could say what they wanted to say and move to the studio,” explained Jinks.

The audience, as described by students in their meeting with Kimbrough, was “over 50, white and Republican,” according to Jinks in an interview with the campus newspaper The O’Colly. Kimbrough told The O’Colly, “I believed the students’ assessment of the audience was accurate.” From The O’Colly:

The theater department advertised the play as a production that “examines the mating rituals of our planet’s most advanced and complicated species,” according to a department brochure.

“I was seeing an evolution of work that was, one, not on the topic that was proposed, (and) two, that tended to be one-sided in its address of transgender issues,” Kimbrough said.

Kimbrough said he visited the class and requested that if the students continued with “The Politics of Dancing,” they keep in mind the type of audience they would be performing for.

“Even though they were moving in a new direction, they were never asked to abandon the topic but simply to proceed from the vantage of mid-October with our current audience in mind,” Kimbrough said. “And I believe when you’re running a business, this is the No. 1 rule. You must create work that has your audience in mind.”

After a weekend of consideration, according to Jinks, the students decided to move the production to the smaller studio. “Ultimately,” said Jinks, “they decided to perform the play they originally wanted to write.”

But that plan hit a snag when Jinks and the students were later informed that their production in the studio would have no production support, because the technical departments, in her description, “could not do two things that close together or at the same time,” with the substituted mainstage show cited as a conflict.

“They were offered the studio and thought they could do that,” said Jinks. “That was the option they were presented, and slowly, bit by bit, it was removed.”

Regarding Kimbrough’s position on the project, Arbaugh wrote, “The idea of him bullying our work until he was ‘comfortable’ with it was too great a cost. However, none of us would have chosen to lose departmental support and our spot in the season. We were all blindsided by the decision and I would say it’s because we gave the “wrong answer.”

Arbaugh continued, saying, “The Politics of Dancing was supposed to be a true test of all our talents. We, as students of the theater, were to use everything we had learned in this in this endeavor. When it was cancelled, it was like a big door was slammed in all of our faces saying, ‘who you are is inappropriate and what you have to contribute has no value.’ So self-esteems suffered and even now there is anxiety in the department.”

So why did the show become This Title Has Been Censored?

“As a class,’ wrote Smoot, “we found that using the source materials we were initially assigned (A Doll’s House and the “Politics Of Dancing” song) were becoming more of a hindrance to our creativity, so we scrapped them from the show. This, along with the struggles we had faced through the process, made the show look completely different from what it was initially intended to be – but that can be expected with devised theatre! We wanted to rename the show in a way that acknowledged the struggles in the process. The final product still discussed gender, but in a much more personal way that drew from many of our personal experiences and life moments interspersed with current events revolving around gender.”

At the show’s single performance, Jinks wrote the following in the program:

During the first few weeks of this current semester the Devised Theatre class was developing a different play than the one you will see today. It was called the The Politics of Dancing and it was to be performed in the Vivia Locke in February of 2016. The devised class would build it and perform it, with me serving as facilitator and director. Over a year ago I made preliminary choices to jump start the process with the class. We were to deconstruct Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House and build a new piece by looking at Ibsen’s work through the lens of gender identification, transgenderism and gender politics – subjects which are omnipresent in the media of late. However other lessons (struggles) interrupted that process.

Jinks believes that some of the problems that arose came from many in the theatre department being unfamiliar with company-created theatre.

“I was working with faculty who have no experience with devising, but I thought we were addressing those needs, “ she said, noting that there was “some rigidity, some pushback even before it was canceled.” Jinks said she discounted that response, calling it “irrelevant.”

“It was so early in the process, the play could have gone in any direction. We had four months. They canceled it because the idea was threatening.”

Jinks described a series of meetings with the dean, the provost, the faculty council and the Office of Equal Opportunity between November and early February.”

“I was met with a wall of silence and denial,” she said, “I’d like them to tell me why it isn’t a denial of academic freedom of speech.”

In February, Jinks met with Kimbrough and the provost.

“I gave both men by action requests, “ she said. “One, Andrew was to acknowledge that an error was made in canceling The Politics of Dancing. Two, Andrew would apologize to the department – faculty, staff and students. Three, the department would write policy so that this doesn’t happen again. Four, there would be a recusal from professional advancement discussion by Andrew over me.”

“Andrew said no to one and two,” she continued. “He did say he would apologize for not having everyone in the same room at the same time to discuss the issue.”

Jinks has been at Oklahoma State University for five years, four of those on a tenure track. She will be up for tenure review in two years.

* * *

Dr. Andrew Kimbrough was contacted by e-mail and asked for an on the record interview regarding this situation. His entire reply was as follows

I’ll be happy to speak to you once our challenge is fully resolved and behind us. I’m learning a lot, and would appreciate more professional response. Thanks.

A second request, noting that his replies to The O’Colly would be the only opportunity for his voice to be heard in this article, received no reply.

Since Dr. Kimbrough asked for more professional response, it seems only appropriate to provide him with some.

My first thought is to say that if indeed you are not already well-versed, Dr. Kimbrough, you should become familiar with the process of devised theatre as an evolutionary process that cannot necessarily be given a label more than half a year in advance and be expected to stick to exactly the original premise. That said, devised theatre must have a place in the OSU theatre department with the full resources of the department, because devised theatre is important both academically and creatively; it is essential that theatre students of today learn about and experience devised, collaborative works to prepare them forprofessional careers.

Please reconsider your statements and overall perspective, Dr. Kimbrough, about the audience being the most important arbiter of what students perform at OSU. Your assertion in The O’Colly, “When you’re running a business, this is the No. 1 rule,” seems profoundly misplaced within an academic theatre program. Students should not be educated according to the perceived preferences of the local consumer marketplace, but rather taught in order to develop their talent, their skills, and their knowledge so that they themselves are competitive in the marketplace of theatre. Indeed, if your position on why we make theatre were voiced by the artistic director of most of America’s not-for-profit theatres, that individual would be questioned by many in the field for abdicating the role of an artistic leader and kowtowing to lowest common denominator sentiments. Yes, there are financial demands on all theatres, and theatre cannot survive without an audience, but those concerns need to operate in balance with the creative impulse. To visit those concerns on students who have paid for a complete theatrical education, with audience satisfaction superseding the education imperative, seems a corruption of the role of academics.

Dr. Kimbrough, your students have the same sentiments as I do.

Jessica Smoot wrote, “He sees this department as a business, and while that has been very beneficial when building the department, it can become dangerous for the creative integrity of the department, which I think is very detrimental to our department. There are ways to warn people to not come if you’re easily offended – add ratings, label shows as avant garde or fringe – but don’t take freedom of speech from the students. We will spend the rest of our lives having to worry about where the money to support our art will come from. Let us have some freedom while we still have the ability to not worry about finance, so that when producing our work becomes harder, we will be creating better quality work from the start because we have already had a chance to practice.”

Joshua Arbaugh wrote, “How could we possibly predict what every audience member came to see and how do we know whether or not there is a completely different audience that has simply been alienated by these ‘choices’ in the past. When someone says, “We need to cater to our audience.” That person is really saying, ‘what’s going to be the most digestible to the kinds of people I personally want to come to these shows.’ My answer is no, the theater season should not be selected to impress Andrew’s hetero-normative white friends.”

Finally Dr. Kimbrough, while one would hope you would do so in all things, it’s particularly incumbent upon you when your department has an endowed chair for underrepresented voices to always demonstrate genuine concern and respect for the students who embody those voices and the professor directly charged with serving them. When you offered the students the opportunity to pursue their vision in a smaller space due to your concerns over the marketability of a piece which appeared to be leaning towards a consideration of gender, and they were subsequently informed that they would receive no technical support and no promotion, you were effectively suppressing art on that subject, regardless of your intent.

I am very fond of Almost Maine (and its author, John Cariani) and I’ve seen Cabaret numerous times, but I don’t think those are shows which deeply explore gender issues and represent efforts at diversity, as you suggested to The O’Colly. You need to redress the impression you have instilled in your students as quickly as possible, by planning for work which explicitly examines that topic, either on the mainstage or for a sustained run in the studio. In addition, you would do well to endorse a new student devised work on the subject of gender in modern society that you will stand behind as firmly as you do The 39 Steps or As You Like It (which does have a bit of gender bending of its own, rendered safe by being 400 years old).

On top of all of this, Dr. Kimbrough, to speak your language for a moment, if money is an important consideration, your actions may be alienating a presumably important donor. To cite an article in The Gayly:

“Literally, the name of this endowed professorship is ‘The Mary Lou Lemon Endowed Professorship for underrepresented voices,’” said Robyn Lemon, daughter of the late Mary Lou Lemon. “Not allowing these students to perform this play contradicts the very reason this entire professorship was set up.”

The bottom line here is that the education of students must come first at a university, and that education must not be simply current but forward-thinking in its philosophy, its pedagogy and its practice. The Politics of Dancing isn’t likely to be resurrected; its moment has passed. But if Oklahoma State University theatre wishes to stand for excellence, if it wants to both compete for students and for the students it graduates to be competitive, it must make very clear that it embraces students no matter their gender identity, their race, the ability or disability – in short, it must be genuinely and consistently inclusive – and it should use its stages to make that clear to the entire university, the local community and beyond.

* * *

One last word: as The O’Colly researched its story on this subject, Kimbrough acknowledged that he attempted to have the story quashed. He was quoted saying, “I think it would be in the best interest of the department if there was no negative publicity of this incident.” When there are charges of censoring a piece of theatre by reducing its potential audience significantly and withdrawing support from it, that’s not a very good time to also try to keep the story from being told. As is so often the case, efforts to avoid negative stories only lead to yet more inquiry and more concern. That holds true for decisions to cease answering questions about a subject in the public eye. Theatre is about telling stories and very often, about revealing truths. The story of The Politics of Dancing is incomplete. It is up to Oklahoma State Theatre to bring it to an honest, open, inclusive and satisfying ending for all concerned.

February 3rd, 2016 § § permalink

Let’s start with the basics: no one can possibly prevent critics from reviewing shows if they want to do. Whether it’s requested or even imposed by theatre company, a venue, a rights holder, or an author, members of the press – just like the public – can always buy a ticket to a theatrical production and express what they think. To actively prevent members of the press from entering a theatre is at least foolhardy if not potentially discriminatory; to prevent anyone from writing or broadcasting their opinion is a denial of their rights to speech. Just so we’re all on the same page.

Ari Fliakos, Kate Valk and Scott Renderer in the Wooster Group production of Pinter’s The Room (Photo by Paula Court)

That’s why a recent press release from The Wooster Group and the Los Angeles venue REDCAT quickly stirred up a hornet’s nest. It stated that the license granted to The Wooster Group for the REDCAT run of the Group’s production of Harold Pinter’s The Room, beginning tomorrow, contained the admonition, “There may be absolutely No reviews of this production; e.g. newspaper, website posts etc.” It also appeared in a press release issued by The Wooster and REDCAT, after an opening paragraph which stated “Samuel French, Inc., which manages the United States rights for Harold Pinter’s work, restricts critics from reviewing the world premiere of the Group’s production of The Room at REDCAT.”

Very little angers and piques the interest of the press more than being told what they can’t do, so it’s no surprise that following the initial word of the issue coming from the website Bitter Lemons, both the Los Angeles Times and New York Times did features on the ostensible critical blackout. But there’s more to the story, which both Times recounted.

In short, The Wooster Group acquired a license for “advance” presentations of The Room last fall, at their home The Performing Garage in New York, where it played an extended run in October and November of 2015. At the time the Group announced that engagement, press releases issued by the company spoke of the planned “premiere” at REDCAT, a return run in New York, and plans to make The Room the first of a trilogy of Pinter productions (The Wooster Group has subsequently spoken of plans to take The Room to France).

However, Bruce Lazarus, executive director of Samuel French, which licenses Pinter’s work in the U.S. on behalf of the Pinter estate’s London agent, says that the announcement of any presentation beyond the original New York license caught the company by surprise. The Wooster Group has confirmed that they had not secured licenses for any of the subsequent engagements beyond November 2015, with their general manager Pamela Reichen writing in an e-mail, “Our plans to do further Pinter pieces besides The Room were preliminary and tentative, when we first announced performances of The Room in New York City. We did not have specific dates for these further productions, and so had not yet made an application for rights to Samuel French.”

Both parties agree that they began discussions about future licenses immediately after French learned of the company’s plans, but the pace and substance of those negotiations and terms are in dispute. What is not in dispute is that by the time rights for the REDCAT engagement were completed, the prohibition against opening the production for review was in place.

When this first hit the press, Lazarus issued a statement that read in part:

Samuel French is licensing agent representing the wishes of the Harold Pinter estate. The Wooster Group announced the Los Angeles production of Pinter’s “The Room” before securing the rights. Had The Wooster Group attempted to secure the rights to the play prior to announcing the production, the estate would have withheld the rights.

Lazarus maintains that the Pinter estate had not been prepared to grant any subsequent license, because the British agent had lined up a “first class” production in the UK, which had an option for a US transfer. Lazarus points out that French could have simply said no. He said that French persuaded the UK agent to allow the LA production, with restrictions. “We said yes because they begged, said Lazarus, “They said, ‘We’ll lose money’.” At first the license was written so as not to permit any promotion of the production, but that was scaled back to being a limitation on reviews.

Queried about the “no reviews” language, Lazarus says French, “made it clear what we meant: don’t invite the critics and don’t provide press tickets. We were under no illusion that the press couldn’t buy a ticket and that if they did so, it wasn’t a breach of contract. We weren’t denying freedom of speech.” That said, whatever the content of the conversations were, in stark black and white contract language, the suggestion of a press exclusion appeared much more blunt, and became even more so when deployed in a press release verbatim. Lazarus allowed that in the future, should such stipulations be made, the language will be more specific.

Ari Fliakos in the Wooster Group production of Pinter’s The Room (Photo by Paula Court)

In the Wooster/REDCAT release, Mark Murphy, Executive Director of REDCAT, says that the review restrictions were “’highly unusual and puzzling,’ adding that, ‘This attempt to restrict critical discussion of such an important production in print and online is deeply troubling, with the potential for severe financial impact.’” In point of fact, review restrictions have become increasingly frequent, for any number of reasons. Just last summer, Connecticut critics were strongly urged not to review A.R. Gurney’s Love and Money at the Westport Country Playhouse because the show’s ‘true’ premiere was to take place immediately following its Connecticut run at New York’s Signature Theatre. Several years ago, national press was “uninvited” from the premiere of Tony Kushner’s The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide at the Guthrie Theatre once a commercial producer optioned the piece. Major press was asked to skip The Bridges of Madison County when it was first seen at Williamstown Theatre Festival. I can think back almost 30 years to a time when I pleaded with a New York Times critic not to attend a production at Hartford Stage, even though local press had attended. And let’s not forget how long Spider-Man: Turn Off The Dark spent in preview before the press finally got fed up and covered it despite the stated preferences of the production. Whether or not one likes the practice of letting producers decide when reviews are or are not “permitted” (Jeremy Gerard of Deadline, previously of Bloomberg and Variety, stakes out his position in a recent column), whether one feels the press is honorable or complicit in how they handle these requests on a case by case basis, it’s hardly a rare practice.

In the case of how the press was handled in connection with The Wooster Group’s unreviewed advance showings of The Room in New York in the fall, Pamela Reichen, general manager of the company, who responded to e-mail questions, writes, “The New York performances were not open to the press. We develop our work over long periods of time that involve work-in-progress showings – like the October-November showings of The Room – at our home theater, The Performing Garage. We only open a show for review in New York or elsewhere once development is complete. The decision not to invite press to the advance showings was our decision, not a stipulation from Samuel French. It was our intention to open the show for review in Los Angeles.”

In a phone conversation about this situation, Jeremy Gerard of Deadline noted, “There’s no other kind of journalism where the journalist says, ‘Is it OK if I report this kind of story?’” That said, the allowance for theatrical productions to be developed and previewed in front of paying audiences has become generally standard practice and important to countless creative artists, the result of a détente between the natural instincts of the press and the creative process of artists.

It’s impossible not to wonder whether the license was actually being denied because of dissatisfaction with the advance presentation in New York by French or the estate. Lazarus says that’s not the case. “No,” he stated, “This is not a value judgment on the production.” That seems consistent with the account by Pamela Reichen, who writes, “We received an appreciative note from the representative of Samuel French who attended an advance showing performance. We have not received any other communication from the estate or Samuel French relating to the concept or execution of our production.”

Asked whether the current denial of right to perform The Room for the foreseeable future after the Los Angeles run would effect their exploration of other Pinter works, Reichen wrote, “Because the rights are not being made available to us, we have no plans to explore other Pinter works. No significant work had begun on them. But our inability to perform The Room in New York or on tour will cause The Wooster Group a significant financial loss. We are a not-for-profit organization, and we fund our own productions. We therefore must recoup our investment over time through long performance runs and touring fees.”

* * *

So let’s cull this down to the basics.

The Wooster Group entered into an agreement to premiere their production of The Room in Los Angeles without having secured the rights to do so, and predicated company finances on presentations of the work beyond the original advance shows in New York in the fall 2015. Whatever the circumstances of the negotiations for those rights, The Wooster Group moved forward with an additional engagement, and was planning for yet more, with no assurance that they could do the piece.

In ultimately granting the rights for the Los Angeles engagement, Samuel French, on behalf of the Pinter estate’s wishes, stipulated that the show at REDCAT should not be open for reviews, but with language that can be construed as a broadly sweeping admonition over any reviews appearing, as opposed to being merely that the venue not facilitate the attendance of critics. Could French and the Pinter estate have allowed the brief LA engagement to proceed with no restrictions, without materially affecting the fortunates of a UK first class production and avoiding the resulting fuss? Sure, but ultimately, it was their call.

In accepting the terms as set forth by French, The Wooster Group and REDCAT apparently still bridled at them, and so instead of asking critics not to attend, they issued a media release which implied an actual, but entirely unenforceable, press ban by French.

I would suggest that The Wooster Group and REDCAT, instead of acquiescing to their agreement and abiding by its spirit, issued the press release they did precisely to incite the press to greater interest in covering The Room, and it worked like a charm. It resulted in more national press than a 10-day run in Los Angeles might have otherwise received, and it prompted the American Theatre Critics Association to issue a statement in support of the right of the arts press to cover work as they see fit. Editors are reportedly debating whether or not to honor – is it a ban or is it a request – the position that the Los Angeles production isn’t officially open for review, even when it’s perfectly clear that they can do as they wish and always could.

Ultimately, The Wooster Group and REDCAT may have won the battle, but they’ve lost the war, since there won’t be any further Pinter work by the company at this time. But they did successfully turn the press account of the situation away from their inability to secure rights on terms they found acceptable into one of press freedom. However, the impact of heightened alertness by the press to requests that work be protected from review in some cases or for some period of time may prove detrimental to other companies and productions in the wake of this scenario. I have always supported the right of artists and companies to explore their work in front of audiences for a reasonable period of time before critics weigh in, and will continue to do so, but in all cases, the press will have the final word. I’m not sure this situation was ultimately beneficial to the arts community because it puts a longstanding, unwritten mutual agreement under the glare of scrutiny that one day may have far-reaching implications.

Howard Sherman is the director off the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

February 3rd, 2016 § § permalink

Let’s start with the basics: no one can possibly prevent critics from reviewing shows if they want to do. Whether it’s requested or even imposed by theatre company, a venue, a rights holder, or an author, members of the press – just like the public – can always buy a ticket to a theatrical production and express what they think. To actively prevent members of the press from entering a theatre is at least foolhardy if not potentially discriminatory; to prevent anyone from writing or broadcasting their opinion is a denial of their rights to speech. Just so we’re all on the same page.

Ari Fliakos, Kate Valk, and Scott Renderer in The Wooster Group’s production of Pinter’s The Room (photo by Paula Court)

That’s why a recent press release from The Wooster Group and the Los Angeles venue REDCAT quickly stirred up a hornet’s nest. It stated that the license granted to The Wooster Group for the REDCAT run of the Group’s production of Harold Pinter’s The Room, beginning tomorrow, contained the admonition, “There may be absolutely No reviews of this production; e.g. newspaper, website posts etc.” It also appeared in a press release issued by The Wooster and REDCAT, after an opening paragraph which stated “Samuel French, Inc., which manages the United States rights for Harold Pinter’s work, restricts critics from reviewing the world premiere of the Group’s production of The Room at REDCAT.”

Very little angers and piques the interest of the press more than being told what they can’t do, so it’s no surprise that following the initial word of the issue coming from the website Bitter Lemons, both the Los Angeles Times and New York Times did features on the ostensible critical blackout. But there’s more to the story, which both Times recounted.

In short, The Wooster Group acquired a license for “advance” presentations of The Room last fall, at their home The Performing Garage in New York, where it played an extended run in October and November of 2015. At the time the Group announced that engagement, press releases issued by the company spoke of the planned “premiere” at REDCAT, a return run in New York, and plans to make The Room the first of a trilogy of Pinter productions (The Wooster Group has subsequently spoken of plans to take The Room to France).

However, Bruce Lazarus, executive director of Samuel French, which licenses Pinter’s work in the U.S. on behalf of the Pinter estate’s London agent, says that the announcement of any presentation beyond the original New York license caught the company by surprise. The Wooster Group has confirmed that they had not secured licenses for any of the subsequent engagements beyond November 2015, with their general manager Pamela Reichen writing in an e-mail, “Our plans to do further Pinter pieces besides The Room were preliminary and tentative, when we first announced performances of The Room in New York City. We did not have specific dates for these further productions, and so had not yet made an application for rights to Samuel French.”

Both parties agree that they began discussions about future licenses immediately after French learned of the company’s plans, but the pace and substance of those negotiations and terms are in dispute. What is not in dispute is that by the time rights for the REDCAT engagement were completed, the prohibition against opening the production for review was in place.

When this first hit the press, Lazarus issued a statement that read in part:

Samuel French is licensing agent representing the wishes of the Harold Pinter estate. The Wooster Group announced the Los Angeles production of Pinter’s “The Room” before securing the rights. Had The Wooster Group attempted to secure the rights to the play prior to announcing the production, the estate would have withheld the rights.

Lazarus maintains that the Pinter estate had not been prepared to grant any subsequent license, because the British agent had lined up a “first class” production in the UK, which had an option for a US transfer. Lazarus points out that French could have simply said no. He said that French persuaded the UK agent to allow the LA production, with restrictions. “We said yes because they begged, said Lazarus, “They said, ‘We’ll lose money’.” At first the license was written so as not to permit any promotion of the production, but that was scaled back to being a limitation on reviews.

Queried about the “no reviews” language, Lazarus says French, “made it clear what we meant: don’t invite the critics and don’t provide press tickets. We were under no illusion that the press couldn’t buy a ticket and that if they did so, it wasn’t a breach of contract. We weren’t denying freedom of speech.” That said, whatever the content of the conversations were, in stark black and white contract language, the suggestion of a press exclusion appeared much more blunt, and became even more so when deployed in a press release verbatim. Lazarus allowed that in the future, should such stipulations be made, the language will be more specific.

Ari Fliakos in The Wooster Group’s production of Pinter’s The Room (photo by Paula Court)

In the Wooster/REDCAT release, Mark Murphy, Executive Director of REDCAT, says that the review restrictions were “’highly unusual and puzzling,’ adding that, ‘This attempt to restrict critical discussion of such an important production in print and online is deeply troubling, with the potential for severe financial impact.’” In point of fact, review restrictions have become increasingly frequent, for any number of reasons. Just last summer, Connecticut critics were strongly urged not to review A.R. Gurney’s Love and Money at the Westport Country Playhouse because the show’s ‘true’ premiere was to take place immediately following its Connecticut run at New York’s Signature Theatre. Several years ago, national press was “uninvited” from the premiere of Tony Kushner’s The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide at the Guthrie Theatre once a commercial producer optioned the piece. Major press was asked to skip The Bridges of Madison County when it was first seen at Williamstown Theatre Festival. I can think back almost 30 years to a time when I pleaded with a New York Times critic not to attend a production at Hartford Stage, even though local press had attended. And let’s not forget how long Spider-Man: Turn Off The Dark spent in preview before the press finally got fed up and covered it despite the stated preferences of the production. Whether or not one likes the practice of letting producers decide when reviews are or are not “permitted” (Jeremy Gerard of Deadline, previously of Bloomberg and Variety, stakes out his position in a recent column), whether one feels the press is honorable or complicit in how they handle these requests on a case by case basis, it’s hardly a rare practice.

In the case of how the press was handled in connection with The Wooster Group’s unreviewed advance showings of The Room in New York in the fall, Pamela Reichen, general manager of the company, who responded to e-mail questions, writes, “The New York performances were not open to the press. We develop our work over long periods of time that involve work-in-progress showings – like the October-November showings of The Room – at our home theater, The Performing Garage. We only open a show for review in New York or elsewhere once development is complete. The decision not to invite press to the advance showings was our decision, not a stipulation from Samuel French. It was our intention to open the show for review in Los Angeles.”

In a phone conversation about this situation, Jeremy Gerard of Deadline noted, “There’s no other kind of journalism where the journalist says, ‘Is it OK if I report this kind of story?’” That said, the allowance for theatrical productions to be developed and previewed in front of paying audiences has become generally standard practice and important to countless creative artists, the result of a détente between the natural instincts of the press and the creative process of artists.

It’s impossible not to wonder whether the license was actually being denied because of dissatisfaction with the advance presentation in New York by French or the estate. Lazarus says that’s not the case. “No,” he stated, “This is not a value judgment on the production.” That seems consistent with the account by Pamela Reichen, who writes, “We received an appreciative note from the representative of Samuel French who attended an advance showing performance. We have not received any other communication from the estate or Samuel French relating to the concept or execution of our production.”

Asked whether the current denial of right to perform The Room for the foreseeable future after the Los Angeles run would effect their exploration of other Pinter works, Reichen wrote, “Because the rights are not being made available to us, we have no plans to explore other Pinter works. No significant work had begun on them. But our inability to perform The Room in New York or on tour will cause The Wooster Group a significant financial loss. We are a not-for-profit organization, and we fund our own productions. We therefore must recoup our investment over time through long performance runs and touring fees.”

* * *

So let’s cull this down to the basics.

The Wooster Group entered into an agreement to premiere their production of The Room in Los Angeles without having secured the rights to do so, and predicated company finances on presentations of the work beyond the original advance shows in New York in the fall 2015. Whatever the circumstances of the negotiations for those rights, The Wooster Group moved forward with an additional engagement, and was planning for yet more, with no assurance that they could do the piece.

In ultimately granting the rights for the Los Angeles engagement, Samuel French, on behalf of the Pinter estate’s wishes, stipulated that the show at REDCAT should not be open for reviews, but with language that can be construed as a broadly sweeping admonition over any reviews appearing, as opposed to being merely that the venue not facilitate the attendance of critics. Could French and the Pinter estate have allowed the brief LA engagement to proceed with no restrictions, without materially affecting the fortunates of a UK first class production and avoiding the resulting fuss? Sure, but ultimately, it was their call.*

In accepting the terms as set forth by French, The Wooster Group and REDCAT apparently still bridled at them, and so instead of asking critics not to attend, they issued a media release which implied an actual, but entirely unenforceable, press ban by French.

I would suggest that The Wooster Group and REDCAT, instead of acquiescing to their agreement and abiding by its spirit, issued the press release they did precisely to incite the press to greater interest in covering The Room, and it worked like a charm. It resulted in more national press than a 10-day run in Los Angeles might have otherwise received, and it prompted the American Theatre Critics Association to issue a statement in support of the right of the arts press to cover work as they see fit. Editors are reportedly debating whether or not to honor – is it a ban or is it a request – the position that the Los Angeles production isn’t officially open for review, even when it’s perfectly clear that they can do as they wish and always could.

Ultimately, The Wooster Group and REDCAT may have won the battle, but they’ve lost the war, since there won’t be any further Pinter work by the company at this time. But they did successfully turn the press account of the situation away from their inability to secure rights on terms they found acceptable into one of press freedom. However, the impact of heightened alertness by the press to requests that work be protected from review in some cases or for some period of time may prove detrimental to other companies and productions in the wake of this scenario. I have always supported the right of artists and companies to explore their work in front of audiences for a reasonable period of time before critics weigh in, and will continue to do so, but in all cases, the press will have the final word. I’m not sure this situation was ultimately beneficial to the arts community because it puts a longstanding, unwritten mutual agreement under the glare of scrutiny that one day may have far-reaching implications.

The two sentences which finish with an asterisk above were inadvertently left out of the post when it first appeared, and were added approximately 90 minutes after this piece first went online. Bruce Lazarus’s title at Samuel French was incorrect in the original post and the text has been altered to reflect his correct position at the company.

Howard Sherman is the director off the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

January 30th, 2016 § § permalink

I am not given to reveries about bygone days or a review of my life choices on my birthdays. The same holds true for New Year’s eve and day. But just in time for my birthday this year, I was forced to look back on a small portion of my past, thanks to an archiving project undertaken by my college newspaper at the University of Pennsylvania. I suspect that many other alumni of The Daily Pennsylvanian are having this experience right now. It just so happens that its debut timed out just prior to my birthday.

I am not given to reveries about bygone days or a review of my life choices on my birthdays. The same holds true for New Year’s eve and day. But just in time for my birthday this year, I was forced to look back on a small portion of my past, thanks to an archiving project undertaken by my college newspaper at the University of Pennsylvania. I suspect that many other alumni of The Daily Pennsylvanian are having this experience right now. It just so happens that its debut timed out just prior to my birthday.

From roughly September 1981 to April of 1984, I wrote for The DP, after breaking through the cliquish barrier that didn’t afford me much opportunity during my freshman year. But once I began writing in earnest, I turned out some 70 pieces over three school years, a pretty good count considering my writing was limited almost entirely to 34th Street, a weekly magazine insert to the main paper where I was also arts editor for two semesters. Unlike the main newspaper, 34th Street of that era was focused on news and entertainment beyond the campus itself.

With my friend John Marshall (l.) at an annual DP dinner circa 1982

It’s worth noting that at the time I wrote for The DP, the internet was inconceivable and there was no prospect that my writing would last more than a couple of days, save for a few bound volumes that might gather dust in the paper’s archives. While I do have a stack of old papers stashed away in a drawer, I never anticipated that my thoughts on entertainment from ages 19 to 22 would ever be generally available to those who wished to seek them out.

Of course, dipping into the archive proved irresistible, and I quickly discovered pieces I remembered rather well, notably my first celebrity interview, with a not yet knighted Ian McKellen, which I had retyped and added to this website a few years ago. I found a number of film and theatre reviews, all written with the hauteur and certainty that one can perhaps only muster at that age. But as I browsed headlines, I was quickly reminded of some pieces, despite a distance of over 30 years, while others were so unfamiliar that I wondered if someone else had written them.

The most surprising pieces are the ones where, while my language may have been infelicitous and is now outmoded, with some unintentional sexism in evidence, it seems my perspective on the arts wasn’t all that different from what it is today. These are the ones from which I want to share a few bits and pieces.

In March 1982, I attempted to address both student performers and critics, tired of the endlessly repeated patterns of a review one day, followed by outraged letters from the subjects of those reviews a couple of days later. In “For Reviewers and Reviewees,” I counseled critics:

If you feel that there is something wrong with a show, say so, but don’t be nasty about it. The search for exciting prose should not extend to slandering the performers. They are, after all, fellow students. A negative observation about an actor is fine, but avoid excess, it does neither the performer’s nor your reputation any good.

Lights, sets, costumes, and, most importantly, direction are all critical elements of a show and involve great commitments by those responsible. These factors of production deserve much more than an offhand summation of “good” or “bad.”

To provide balance, I advised those involved in student theatre:

Remember that the reviewers also try to be as professional as possible. That means they must say what they feel, be it pleasant or uncomplimentary. Just as a director can choose to emphasize any facet of a script in production, a writer can focus on any element of a show that he deems worthy of mention.

Getting reviewed is an unavoidable part of performing (unless a producer decides not to let reviewers in). Right or wrong, intelligent or irresponsible, reviews are almost inextricably linked to the performing arts. Also, reviewers must speak with authority, since only they can justify the personal opinions that they write about. If a writer hates, for example, the score of West Side Story, he should say so, regardless of what anyone else thinks.

Two days after he received the Pulitzer Prize in 1982 for A Soldier’s Play, I had the opportunity to attend a small press gathering with Philadelphia resident Charles Fuller, held at Freedom Theatre, a company focused on work by African-American artists. I reported the event, in part, as follows:

Fuller says that at first he wasn’t sure everyone would like A Soldier’s Play, which is currently being staged by New York City’s Negro Ensemble Company. “We wanted to take a chance,” he says. “It begins to deal with some of the complexities of black life in this country.”

Fuller is only the second black playwright to win the prize. “It’s an important step for me as a playwright – I don’t know what effect it will have on theater as a whole.” As for Fuller’s own effect on theater, he wants to “talk about black people as human beings. We’ve been talked about as statistics for so long.”

Fuller says that his writing develops from his hopes for society. “It’s a severe racial pride. But it’s not racist.”

I presumed to opine about the state of Philadelphia theatre from a historical perspective, in the days before many of the vibrant companies that now occupy the city had begun. This was hubris, of course. But take note of my concern about ticket pricing.

Philadelphia theater ain’t what it used to be. Thank God.

After skyrocketing financial restraints severely depleted the number of pre-Broadway tryout productions here, Philadelphia in the 1970’s was left with but a few large Broadway-type houses and very little to put in them. Smaller companies tried in vain to bridge the gap, failing for a variety of economic and artistic reasons. And Andre Gregory’s Theatre of the Living Arts – the city’s only interesting theater of the 60’s – got too weird for patrons and fizzled out over a decade ago.

Pre-Broadway tours still come around every so often, with Anthony Quinn’s Zorba revival highlighting the past season and an Angela Lansbury Mame promised for the summer. Less discriminating theatrical patrons will probably be sated with the national tours that appear regularly with watered-down versions of Broadway smash hits, although paying 35 dollars for Andy Gibb in the otherwise wonderful Joseph and The Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat should be considered a criminal offense.

I had the opportunity to interview Spalding Gray, relatively early in his solo performing career, in conjunction with one of his monologues that few people have even heard of. It was performed at a venue called The Wilma Project, now known at The Wilma Theatre.

“I am a sort of actor-anthropologist, a mixture of story-teller and monologuist,” Gray says, summing up his unique performing style. He talks directly to the audience from memory, using no script. Unlike previous one-man shows. Gray portrays no one other than himself as he “re-remembers” his life experiences for audiences.

Gray will deliver his piece, In Search of the Monkey Girl, for a live audience the first lime this weekend. He has performed it four times into a tape recorder, in order to provide a text for a series of sideshow photographs shot by Randall Leverson which were printed in Aperture magazine. “It was strange,” Gray says. “He had worked for ten years and I only took ten days.”

In the course of his journey to the state fair, Gray was attracted to a trio of middle class preachers. “They had lost their drug rehabilitation center as a result of the Reagan cutbacks and were working in the sideshow in order to save up enough money to reopen it.” he says. In the meantime, Gray adds, “they were geeks, sucking on the heads of fifteen foot snakes.”

I am glad to find that I was concerned about the portrayal of women on screen at a young age (while completely misunderstanding a film’s genre), writing the following about 48 HRS, the Walter Hill movie that introduced Eddie Murphy to the big screen:

Compounding this inept rehash of the hard-boiled detective genre is the incredibly sexist treatment of women. The few females presented are either climbing into or out of bed, making 48 HRS the most callously anti-feminist film in years.

Even live theatre, or taped productions, something that is once again a current topic, caught my eye, and my thoughts today aren’t all that different than these from 1982:

First, in the case of NBC’s offerings, is it really necessary for T.V. to air the programs live? Granted, live productions were the rule in the fifties, but now editing allows for choosing the best of many takes. Finer quality could be attained from editing together several different performances of the same work. Nowadays live broadcasts are novelties masquerading as high art.

Second, judging by the cable tapings of stage shows, can true justice be done to a work that is primarily staged for one viewing perspective? The limitations imposed by stage architecture result in a radical lessening of camera angles, which have traditionally been used by T.V. and cinema to add to a production. One play shown on HBO included shots from the back of the theater, rendering the figures on the stage almost invisible. Stage shows should be directed again if they are to be adapted for the camera.

Third, what of realism: will a T.V. audience accept “theatricality’?…

…It is commendable that T.V. is attempting to bring theater to a mass audience, but it is a shame that the artistic qualities and capabilities of both media are being compromised in the process. While the public should strongly support the revival of television drama, perhaps theater is belter off where it belongs: on the stage.

I do remember my lengthy feature on the issue of book banning and censorship, which presaged some of my work at the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School on arts censorship. I spoke with figures I didn’t care for at the time (and still don’t), such as Phyllis Schlafly and a spokesman for Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority. Frankly, I wish I’d spoken to more anti-censorship figures as I look back at the article, but my summing up wasn’t bad, though I deeply regret the absence of two asterisks at the time, or my use of a racial slur at all, when referring to Mark Twain’s character of Jim in Huckleberry Finn:

In Texas this past August, a couple who spend their time reviewing school books for “questionable” content voiced disapproval of a textbook that describes the medicinal qualities of the drug insulin. They said that the reference will lead students to believe that all drugs are sale and beneficial.

Earlier this year Studs Turkel visited a high school in Girard, Pennsylvania, to talk with students and teachers about the movement to remove Working from twelfth grade reading lists. His appearance convinced authorities to restore the book temporarily, but they are still seeking a means by which Working can be banned.

The above examples are not isolated incidents. The rapidly rising wave of book banning and censorship threatens to engulf the U.S.’s entire elementary and secondary education system. There are ten times as many books banned today as there were only a decade ago. Books are being withheld or purged from classrooms and school libraries according to the dictates of various parental and political interest groups…

…No matter how big the issue becomes, the controversy boils down to three issues; what rights the Constitution guarantees to students, what parents want their children to read, and what censorship means. Is it the removal of traditional values from books or the removal of books from libraries? And who will decide?

Finally, in a piece I had completely forgotten, I find that my work at the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts was not something that emerged late in life, but had actually been on my mind a long time ago as well. It’s important to remember that at the time, “handicapped” was still emerging to replace “crippled”; “disabled” was not yet identified as the best term. There’s some hyperbole here, and outmoded and awkward expression, but the core of my thinking, I hope, rings true.

An actor’s greatest fear, short of death, is probably of being disfigured in some terribly obvious way. A facial scar, a missing limb, even something so simple as nodes on the vocal cords can send the finest actor into oblivion. But a handful of actors over the past several decades have proven that the handicapped are still superb performers who do not deserve to be shunned by an industry that has based itself on physical perfection…

…Currently, Adam Redfield is touring in the play Mass Appeal, despite an obvious case of neuralgia which has paralyzed the right side of his face. While the condition is temporary, it is to the producers’ credit that they have allowed Redfield to continue in the role. It also proves that the handicapped should be allowed to perform in “normal” roles, even if they do not quite fit the character description, it is sobering to remember that had Redfield had the neuralgia before his audition, he probably would have been quickly discarded.

Are we fully formed as people in college? Certainly not. But it seems that many of the same interests and issues that moved me to to write 30 years ago remain important to me now. I wonder if anything I said in the 80s, or today, will still hold up another 30 years on. But I’d like to still be writing, and I wonder what will be in my mind in 2046.

November 16th, 2015 § § permalink

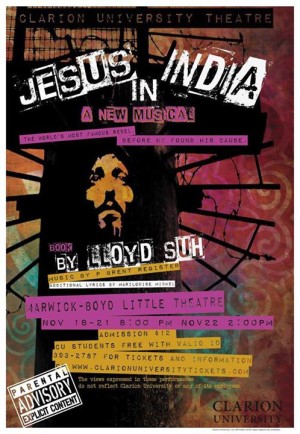

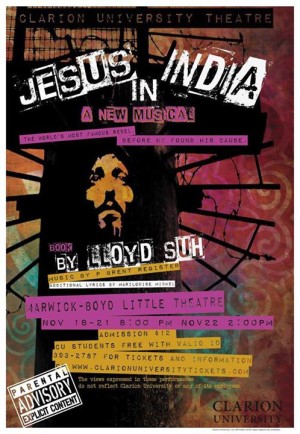

Poster for Jesus in India at Clarion University

“What will you learn?” asks the home page of the website of Clarion University in Pennsylvania. In the wake of the school’s handling of the casting of white students in Asian roles in Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India, and the playwright’s withdrawal of production rights upon learning this fact, it’s unclear at best, disturbing at worst, to consider what Clarion wants students to learn about race and about the arts.

Based on what is appearing in the press, they are learning to blame artists for wanting to see their work represented accurately. They are learning to attack artists when the artists defend their work. They are learning that a desire to see race portrayed with authenticity is irrelevant in an academic setting. They are learning that Clarion seems unaware of the issues that have fueled racial unrest on campuses around the country, most recently with flashpoints at the University of Missouri and Yale University. They are learning that when a community is overwhelmingly white, concerns about race aren’t perceived as valid.

In an essay published in the Chronicle of Higher Education on Friday, Marilouise Michel, professor of theatre and director of the canceled production, wrote, “I have intentionally left out the name of the playwright and the piece that we were working on as I do not wish to provide him with publicity at the expense of the fine and viable work of our students.” What’s peculiar about that statement is that until 1:30 pm that day, when he released a statement, the playwright hadn’t sought for this issue to be public in any way. It was Clarion that had contacted the press, Clarion which had released his correspondence with Michel, and Clarion which used a professional public relations firm to issue a statement about the situation from the university and its president. It reads, in part:

The university claims their intent from the start was to honor the integrity of the playwright’s work, and the contract for performance rights did not specify ethnically appropriate casting. Despite the university’s attempt to give Suh a page in the program to explain his casting objections and a stage speech given by a university representative on the cast’s race, Suh rejected any solutions other then removing the non-Asian actors or canceling the production.

“We have no further desire to engage with Mr. Suh, the playwright, as he made his position on race to our theater students crystal clear,” says Dr. Karen Whitney, Clarion University President. “I personally prefer to invest my energy into explaining to the student actors, stage crew and production team members why the hundreds of hours they committed to bringing ‘Jesus in India’ to our stage and community has been denied since they are the wrong skin color

This insidious inversion of racial justice is profoundly troubling. The play, set in India, has three characters named “Gopal,” “Mahari/Mary,” and “Sushil,” a strong indication of their race. Suh maintains that the university was asked about their plans to cast those roles, and his agent Beth Blickers says no answer was ever given. But when the playwright finally drew a line over racial representation, he was the one who was supposedly denying skin color, when it was Michael’s personal interpretation of the play, against clear evidence and requests, which was ignoring race in the play. So now, one must wonder whether Dr. Whitney will be spending time explaining to the students of color on campus why she is vigorously defending the practice of “brownface” on campus (white actors portraying Indian characters, regardless of whether color makeup is actually employed) and attacking a playwright of color for decrying the practice.

To be clear, there is undoubtedly great disappointment and pain among the students and crew who had been working on the production. Anyone in the arts will surely sympathize with them for having invested time and effort towards a production that they surely undertook with the best of intentions. But they were, most likely unwittingly, made complicit in the act of denying race and denying an artist’s wishes.

In the university’s press release, the extremely small Asian population of the school is noted (at 0.6% of the student body), as it has been previously in many reports. That no Asian students auditioned should not have been surprising, nor should it have been license to substitute actors of others races as a result. Any director who is part of an academic theatre program has a very good idea of what talent may be available, and often productions are chosen accordingly. So it is not the failure of Asian students to audition to blame for the inaccurate racial casting. More correctly it was the decision to produce a play which clearly called for Asian characters and the assessment that race didn’t matter that created this situation – not Lloyd Suh or any student.

In the Chronicle, Harvey Young, chair of the theatre department at Northwestern University, admittedly a more urban school, says the following regarding racial casting on campus:

“That is the magic of the university — to introduce people to a variety of perspectives and points of view.”

But at Northwestern, Mr. Young said, the department uses a variety of strategies to avoid what could be racially problematic casting. The department has hired outside actors to play some roles and serve as mentors to students, reached out to minority groups to let them know about acting opportunities, and staged readings at which only voices are represented.

“The goal is to devise strategies that allow you to engage the work while being aware of whatever limits exist,” Mr. Young said.

In her essay for the Chronicle, Michel wrote, “Perhaps Shakespeare would wince at a Western-style production of The Taming of the Shrew, but he never told us we couldn’t. He never said Petruchio couldn’t be black, as he was in the 1990 Delacorte Theater production starring Morgan Freeman.” This is a specious and rather ridiculous argument, since Shakespeare’s work is not under copyright and can be cast or altered in any way one wishes. While there are certainly examples of actors of color taking on roles written for or traditionally played by white actors – NAATCO’s recent Awake and Sing with an all-Asian cast playing Clifford Odets’s Jewish family, the Broadway revival of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof with a black cast playing Tennessee Williams’s wealthy southern family – they were done with the express approval of the rights holders. That these productions were in New York as opposed to Clarion, Pennsylvania makes no difference as to the author’s rights. What we have not seen is an all-white Raisin in the Sun, either because no one has been foolish enough to attempt it or because the Lorraine Hansberry estate hasn’t allowed it.

Clarion’s press efforts have certainly paid off in the local community, with three news/feature stories in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (here, here and here) as well as an editorial, along with two features (here and here) in the Chronicle of Higher Education, in addition to the aforementioned essay. That the Post-Gazette’s editorial sides entirely with Clarion is no surprise, since the university was driving the story; that it fails to take into account any reporting which runs counter to Clarion’s narrative, and indeed repeats them, is shameful, a disservice to the Pittsburgh community. That the Chronicle of Higher Education ran Professor Michel’s essay, another one-sided account of the situation, is problematic, but the headline (whether it is theirs or Michel’s), “How Racial Politics Hurt My Students,” is a clarion call for paranoia about race. It ignores the fact that the problems arose from a failure to respect the work and the playwright, that the issue is based not in politics, but in art, and that the author saw his work being defaced and stood up for it. There have been countless other reports on the situation. That this has engendered vile racist outpourings online, especially in comments sections and on Facebook, and in some press accounts is the result of the university’s irresponsible spin.

Universities are in no way exempted from professional standards when it comes to licensing and producing shows; to claim otherwise is to suggest that campuses are bubbles in which the rules of the real world do not apply. While classrooms are absolutely places for exploration and discovery, theatre productions of complete works for audiences are not just educational exercises. Students need to be taught creative and legal responsibility towards plays (and musicals) and their authors, not encouraged to take scripts as mere suggestions to be molded in any way a director wishes. When it comes to race, this incident and the recent Kent State production of The Mountaintop will now insure that every playwright who cares about the race of their characters will be extremely explicit in their directions, but that doesn’t excuse directors who look for loopholes to justify willfully ignoring indications in existing texts.

It’s my understanding that there has been new contact between Michel and Suh, though I am not party to its nature or content. It’s worth noting that in the third Post-Gazette story, it is reported that “Ms. Michel took to Facebook Saturday to ask “that any negative or mean-spirited posts or contact towards Mr. Suh be ceased. We are both artists trying to serve a specific community and attacking him helps no one.” That’s a responsible position to take, but it should be expanded to include negative posts or contact about the accurate portrayal of race in theatre, since they are flourishing in the wake of this incident.

It is also now time for the university to explain the truth about why the production was shut down, namely a failure to respect the artistic directive of the playwright; insure that this incident and the rhetoric surrounding it hasn’t been a license for anyone to marginalize their students of color; and begin truly addressing equity and diversity on their campus. Regardless of the racial makeup of their community or student body, they need to be setting an example and creating a better environment for all students, not feeding into narratives of racial divisiveness.

Update, November 18, 7 pm: Earlier today, the Dramatists Guild of America released a statement regarding the organization’s position on casting and copyright, signed by Guild president Doug Wright. It reads, in part:

One may agree or disagree with the views of a particular writer, but not with his or her autonomy over the play. Nor should writers be vilified or demonized for exercising it. This is entirely within well-established theatrical tradition; what’s more, it is what the law requires and basic professional courtesy demands.

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts School of Drama.

November 11th, 2015 § § permalink

Joe Bannister & Leon Annor in As You Like It at the National Theatre (Photo: Johan Persson)

Four words. Why do four words bother me so much?