December 3rd, 2015 § § permalink

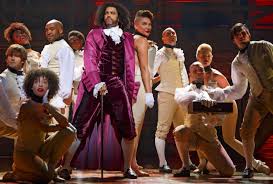

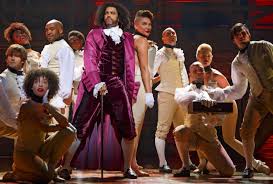

Renée Elise Goldsberry, Lin-Manuel Miranda and Phillipa Soo in Hamilton (Photo by Joan Marcus)

In the wake of the recent casting controversies over Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop and Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India, there have been a number of online commenters who have cited Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton as a justification for their position in the debate. What’s intriguing is that Hamilton has been offered up both as evidence of why actors of color must have the opportunity to play both characters or color and characters not necessarily written as characters of color – but it has also been used to say that anything goes, and white actors should be able to play characters of color as well.

In the Broadway production of Hamilton, the characters are historical figures who were all known to have been white, but they are played by actors of many races and ethnicities, notably black, Latino and Asian. My position on non-traditional (or color-blind or color-specific) casting is that it is not a “two-way street,” and that the goal is to create more opportunities for actors of color, not to give white actors the chance to play characters of color.

As it happens, I had an interview scheduled with Miranda last week, the night before Thanksgiving. Race wasn’t the subject at all, however. We were speaking about his experiences in, and views on, high school theatre, for Dramatics magazine, a publication of the Educational Theatre Association (ask a high school thespian for a copy). But when I finished the main interview, and had shut off my voice recorder, I asked Miranda if he would be willing to make any comment regarding the recent casting situations that had come to light. He was familiar with The Mountaintop case, but I had to give him an exceptionally brief précis of what had occurred with Jesus in India. He said he would absolutely speak to the issue, and I had to hold up my hand to briefly pause him as he rushed to start speaking, while I started recording again.

“My answer is: authorial intent wins. Period,” Miranda said. “As a Dramatists Guild Council member, I will tell you this. As an artist and as a human I will tell you this. Authorial intent wins. Katori Hall never intended for a Caucasian Martin Luther King. That’s the end of the discussion. In every case, the intent of the author always wins. If the author has specified the ethnicity of the part, that wins.

“Frankly, this is why it’s so important to me, we’re one of the last entertainment mediums that has that power. You go to Hollywood, you sell a script, they do whatever and your name is still on it. What we protect at the Dramatists Guild is the author’s power over their words and what happens with them. It’s very cut and dry.”

This wasn’t the first time Miranda and I have discussed racial casting. Last year, we corresponded about it in regard to high school productions of his musical In The Heights, and his position on the show being done by high schools without a significant Latino student body, which he differentiated from even college productions.

Lin-Manuel Miranda, Karen Olivo and the company of In The Heights (Photo by Joan Marcus)

“The joy of In The Heights runs both ways to me,” he wrote me in early 2014. “When I see a school production with not a lot of Latino students doing it, I know they’re learning things about Latino culture that go beyond what they’re fed in the media every day. They HAVE to learn those things to play their parts correctly. And when I see a school with a huge Latino population do Heights, I feel a surge of pride that the students get to perform something that may have a sliver of resonance in their daily lives. Just please God, tell them that tanning and bad 50’s style Shark makeup isn’t necessary. Latinos come in every color of the rainbow, thanks very much.

“And I’ve said this a million times, but it bears repeating: high school’s the ONE CHANCE YOU GET, as an actor, to play any role you want, before the world tells you what ‘type’ you are. The audience is going to suspend disbelief: they’re there to see their kids, whom they already love, in a play. Honor that sacred time as educators, and use it change their lives. You’ll be glad you did.”

Daveed Diggs and the company of Hamilton (Photo by Joan Marcus)

Anticipating the flood of interest in producing Hamilton once the Broadway production and national tours have run their courses, I asked Miranda whether the acting edition of the script of Hamilton will ultimately be specific about the cast’s diversity, and whether, either at the college level or the professional level, he would foresee a situation where white actors were playing leading roles.

“I don’t have the answer to that. I have to consult with the bookwriter, who is also me,” he responded. “I’m going to know the answer a little better once we set up these tours and once we set up the London run. I think the London cast is also going to look like our cast looks now, it’s going to be as diverse as our cast is now, but there are going to be even more opportunities for southeast Asian and Asian and communities of color within Europe that should be represented on stage in that level of production.

“So I have some time on that language and I will find the right language to make sure that the beautiful thing that people love about our show and allows them identification with the show is preserved when this goes out into the world.”

Authorial intent, y’all. Authorial intent.

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

December 3rd, 2015 § § permalink

Phillipa Soo, Lin-Manuel Miranda and Renée Elise Goldsberry in Hamilton (Photo by Joan Marcus)

In the wake of the recent casting controversies over Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop and Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India, there have been a number of online commenters who have cited Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton as a justification for their position in the debate. What’s intriguing is that Hamilton has been offered up both as evidence of why actors of color must have the opportunity to play both characters or color and characters not necessarily written as characters of color – but it has also been used to say that anything goes, and white actors should be able to play characters of color as well.

In the Broadway production of Hamilton, the characters are historical figures who were all known to have been white, but they are played by actors of many races and ethnicities, notably black, Latino and Asian. My position on non-traditional (or color-blind or color-specific) casting is that it is not a “two-way street,” and that the goal is to create more opportunities for actors of color, not to give white actors the chance to play characters of color.

As it happens, I had an interview scheduled with Miranda last week, the night before Thanksgiving. Race wasn’t the subject at all, however. We were speaking about his experiences in, and views on, high school theatre, for Dramatics magazine, a publication of the Educational Theatre Association (ask a high school thespian for a copy). But when I finished the main interview, and had shut off my voice recorder, I asked Miranda if he would be willing to make any comment regarding the recent casting situations that had come to light. He was familiar with The Mountaintop case, but I had to give him an exceptionally brief précis of what had occurred with Jesus in India. He said he would absolutely speak to the issue, and I had to hold up my hand to briefly pause him as he rushed to start speaking, while I started recording again.

“My answer is: authorial intent wins. Period,” Miranda said. “As a Dramatists Guild Council member, I will tell you this. As an artist and as a human I will tell you this. Authorial intent wins. Katori Hall never intended for a Caucasian Martin Luther King. That’s the end of the discussion. In every case, the intent of the author always wins. If the author has specified the ethnicity of the part, that wins.

“Frankly, this is why it’s so important to me, we’re one of the last entertainment mediums that has that power. You go to Hollywood, you sell a script, they do whatever and your name is still on it. What we protect at the Dramatists Guild is the author’s power over their words and what happens with them. It’s very cut and dry.”

This wasn’t the first time Miranda and I have discussed racial casting. Last year, we corresponded about it in regard to high school productions of his musical In The Heights, and his position on the show being done by high schools without a significant Latino student body, which he differentiated from even college productions.

Lin-Manuel Miranda, Karen Olivo and the company of In The Heights (Photo by Joan Marcus)

“The joy of In The Heights runs both ways to me,” he wrote me in early 2014. “When I see a school production with not a lot of Latino students doing it, I know they’re learning things about Latino culture that go beyond what they’re fed in the media every day. They HAVE to learn those things to play their parts correctly. And when I see a school with a huge Latino population do Heights, I feel a surge of pride that the students get to perform something that may have a sliver of resonance in their daily lives. Just please God, tell them that tanning and bad 50’s style Shark makeup isn’t necessary. Latinos come in every color of the rainbow, thanks very much.

“And I’ve said this a million times, but it bears repeating: high school’s the ONE CHANCE YOU GET, as an actor, to play any role you want, before the world tells you what ‘type’ you are. The audience is going to suspend disbelief: they’re there to see their kids, whom they already love, in a play. Honor that sacred time as educators, and use it change their lives. You’ll be glad you did.”

Daveed Diggs and the company of Hamilton (Photo by Joan Marcus)

Anticipating the flood of interest in producing Hamilton once the Broadway production and national tours have run their courses, I asked Miranda whether the acting edition of the script of Hamilton will ultimately be specific about the cast’s diversity, and whether, either at the college level or the professional level, he would foresee a situation where white actors were playing leading roles.

“I don’t have the answer to that. I have to consult with the bookwriter, who is also me,” he responded. “I’m going to know the answer a little better once we set up these tours and once we set up the London run. I think the London cast is also going to look like our cast looks now, it’s going to be as diverse as our cast is now, but there are going to be even more opportunities for southeast Asian and Asian and communities of color within Europe that should be represented on stage in that level of production.

“So I have some time on that language and I will find the right language to make sure that the beautiful thing that people love about our show and allows them identification with the show is preserved when this goes out into the world.”

Authorial intent, y’all. Authorial intent.

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

December 2nd, 2015 § § permalink

Jonathan Larson’s Rent at Eastern Tennessee State University (Photo by Larry Smith)

I assume most people, either as a child heard, or as a parent deployed, the timeworn phrase, “If someone told you to jump off the Brooklyn Bridge, would you do it?” My parents had a variant along the same lines: “Just because other people do it doesn’t make it right.”

I am reminded of this phrase as it seems every week lately I hear about another instance of a theatre director altering a script or overriding an author’s clear intent; the recent run of examples has been with college-affiliated productions. I wonder whether the people responsible have had others set the wrong example, and they felt they could just join in, or if they just started doing it and, since they were never challenged or caught, kept it up.

The most prominent incidents have been with Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop, at a community theatre affiliated with Kent State University’s Department of Pan-African Studies, and with Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India at Clarion University. In both of those cases, the issue was the casting of roles written as characters of color.

In a markedly less fraught situation which didn’t generate any major headlines, a production of Rent at Eastern Tennessee State University, just before Thanksgiving, had to cancel one day of a five-day run because the show’s licensing house learned of a scene that had been cut without approval. The lost day was used to restore the scene in question, as reported by the campus newspaper, The East Tennessean.

In its coverage, the paper quoted Patrick Cronin, the production’s director and the Program Director of Communication and Performance at the school, as to what had taken place.

“I have directed hundreds of shows, and made many cuts before,” Cronin said. “So, I did the same with the street scenes [in ‘Rent’] because we did not have enough actors to make those scenes interesting.”

At the end of the article, Cronin was again quoted:

“I have a young cast who were able to add six pages of material in two days,” Cronin said. “I am just grateful that we got the show on and that we caught the mistake I had made.”

While the school paper didn’t draw attention to the inconsistency, it’s worth noting that Cronin said that what he did was a mistake, but earlier on he had said it was consistent with what he’d done numerous times before. Secondly, it’s not Cronin who caught the mistake, but someone at the school familiar enough with what had been taking place in the rehearsal room – and with copyright and licensing law – to contact Music Theatre International and give them a heads up about the unauthorized alteration. Finally, isn’t it interesting to note that a solution was found to the supposedly problematic scene, in almost no time at all.

Some might accuse me of conflating the first two examples, which turn on the issue of race in casting, with the third, which was the excision of a scene. But I’d argue that they’re all of a piece, because they involve directors either misinterpreting works or placing their own sensibility above that of the author, be it for practical, aesthetic or intellectual reasons. While I don’t have press reports I can bring forward, I can say that since I began writing on this topic, I have been told numerous anecdotes about shows in academic settings that have been altered for any number of reasons, all without approval.

So I have to wonder: are some theatre programs and theatrical groups at the college level advancing the belief that scripts can be altered at will, or elements ignored? Are schools teaching both the legal and ethical implications of artists’ rights and copyright law, not just to playwrights but to all of those who study theatre? Have bad practices begotten yet further bad practices? Are there professors and program directors who believe that anything produced on a campus falls under the fair use exemption for educational purposes under the copyright laws?

Lest anyone think I’m advocating for slavish recreations of original productions or less than fruitful collaborations on new works, I should state that I most assuredly am not. I want to see directors, whether students or faculty (and, for that matter, professionals as well), have the opportunity to undertake creative productions that will challenge the artists involved and the audiences they attract. I want to see works reinvented, but in ways which reveal something new that is supported by the text, rather than overriding it. That said, I am troubled by a sense that in some cases (I’m not saying that this applies to every production at every school) something approaching film’s auteur theory, in which the director of a movie is seen as its primary author, is filtering into theatre at the pre-professional level in a way which diminishes or disregards the importance and rights of authors.

I have a genuine desire to know the answers to some of the questions I’ve asked above. I’d be interested in those answers not only from faculty but from students both past and present. What is being taught about the relationship between playwright and director, regardless of whether the latter is present in rehearsals, available via computer or phone, otherwise engaged, or even dead but still protected by copyright? I ask because I think we all have a lot to learn. I’d like to hear from you, either on the record or confidentially; you can write to me here.

Oh, since I started with timeworn phrases, let me finish with one as well, which believe it or not I’ve heard more than a few times over my career: “Better to ask for forgiveness than to ask for permission.” These are not, I hope you’ll agree, words to live by. Even if some seem to.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

December 2nd, 2015 § § permalink

Jonathan Larson’s Rent at Eastern Tennessee State University (Photo by Larry Smith)

I assume most people, either as a child heard, or as a parent deployed, the timeworn phrase, “If someone told you to jump off the Brooklyn Bridge, would you do it?” My parents had a variant along the same lines: “Just because other people do it doesn’t make it right.”

I am reminded of this phrase as it seems every week lately I hear about another instance of a theatre director altering a script or overriding an author’s clear intent; the recent run of examples has been with college-affiliated productions. I wonder whether the people responsible have had others set the wrong example, and they felt they could just join in, or if they just started doing it and, since they were never challenged or caught, kept it up.

The most prominent incidents have been with Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop, at a community theatre affiliated with Kent State University’s Department of Pan-African Studies, and with Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India at Clarion University. In both of those cases, the issue was the casting of roles written as characters of color.

In a markedly less fraught situation which didn’t generate any major headlines, a production of Rent at Eastern Tennessee State University, just before Thanksgiving, had to cancel one day of a five-day run because the show’s licensing house learned of a scene that had been cut without approval. The lost day was used to restore the scene in question, as reported by the campus newspaper, The East Tennessean.

In its coverage, the paper quoted Patrick Cronin, the production’s director and the Program Director of Communication and Performance at the school, as to what had taken place.

“I have directed hundreds of shows, and made many cuts before,” Cronin said. “So, I did the same with the street scenes [in ‘Rent’] because we did not have enough actors to make those scenes interesting.”

At the end of the article, Cronin was again quoted:

“I have a young cast who were able to add six pages of material in two days,” Cronin said. “I am just grateful that we got the show on and that we caught the mistake I had made.”

While the school paper didn’t draw attention to the inconsistency, it’s worth noting that Cronin said that what he did was a mistake, but earlier on he had said it was consistent with what he’d done numerous times before. Secondly, it’s not Cronin who caught the mistake, but someone at the school familiar enough with what had been taking place in the rehearsal room – and with copyright and licensing law – to contact Music Theatre International and give them a heads up about the unauthorized alteration. Finally, isn’t it interesting to note that a solution was found to the supposedly problematic scene, in almost no time at all.

Some might accuse me of conflating the first two examples, which turn on the issue of race in casting, with the third, which was the excision of a scene. But I’d argue that they’re all of a piece, because they involve directors either misinterpreting works or placing their own sensibility above that of the author, be it for practical, aesthetic or intellectual reasons. While I don’t have press reports I can bring forward, I can say that since I began writing on this topic, I have been told numerous anecdotes about shows in academic settings that have been altered for any number of reasons, all without approval.

So I have to wonder: are some theatre programs and theatrical groups at the college level advancing the belief that scripts can be altered at will, or elements ignored? Are schools teaching both the legal and ethical implications of artists’ rights and copyright law, not just to playwrights but to all of those who study theatre? Have bad practices begotten yet further bad practices? Are there professors and program directors who believe that anything produced on a campus falls under the fair use exemption for educational purposes under the copyright laws?

Lest anyone think I’m advocating for slavish recreations of original productions or less than fruitful collaborations on new works, I should state that I most assuredly am not. I want to see directors, whether students or faculty (and, for that matter, professionals as well), have the opportunity to undertake creative productions that will challenge the artists involved and the audiences they attract. I want to see works reinvented, but in ways which reveal something new that is supported by the text, rather than overriding it. That said, I am troubled by a sense that in some cases (I’m not saying that this applies to every production at every school) something approaching film’s auteur theory, in which the director of a movie is seen as its primary author, is filtering into theatre at the pre-professional level in a way which diminishes or disregards the importance and rights of authors.

I have a genuine desire to know the answers to some of the questions I’ve asked above. I’d be interested in those answers not only from faculty but from students both past and present. What is being taught about the relationship between playwright and director, regardless of whether the latter is present in rehearsals, available via computer or phone, otherwise engaged, or even dead but still protected by copyright? I ask because I think we all have a lot to learn. I’d like to hear from you, either on the record or confidentially; you can write to me here.

Oh, since I started with timeworn phrases, let me finish with one as well, which believe it or not I’ve heard more than a few times over my career: “Better to ask for forgiveness than to ask for permission.” These are not, I hope you’ll agree, words to live by. Even if some seem to.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.