September 15th, 2015 § § permalink

Please consider the following two statements.

- In a description of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado: “The location is a fictitious Japanese town.”

- “There are no ethnically specific roles in Gilbert and Sullivan.”

The conflict between these two statements seems fairly obvious since even in a fictitious Japanese village, the residents are presumably Japanese, and that is indeed ethnically specific, even if they are endowed with nonsensical names that may have once sounded vaguely foreign to the British upper crust.

The NYGASP Production of The Mikado

Now one could try to explain away this dissonance by saying that the statements are drawn from conflicting sources, however they are both taken from the website of the New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players. The company, which has been producing the works of G&S in Manhattan for 40 years, will be mounting their production of The Mikado at NYU’s Skirball Center from December 26 of this year through January 2, 2016, six performances in total.

It is hardly news that The Mikado is a source of offense and insult to the Asian-American community, both for its at best naïve and at worst ignorant cultural appropriation of 19th century Japanese signifiers, as well as for the seeming intransigence of 20th and 21st century producers when it comes to attempting to contextualize or mitigate how the material is seen today. Particularly awful is the ongoing practice of utilizing yellowface (Caucasian actors made up to appear “Asian”) in order to produce the show, instead of engaging with Asian actors to both reinterpret and perform the piece. Photos of past productions by the NY Gilbert & Sullivan Players suggest their practice is the former.

“History!,” some cry, “Accuracy to the period!” That’s the same foolish argument recently spouted by director Trevor Nunn to explain why his new production of Shakespeare history plays featured an entirely white cast of 22. “But The Mikado is really not about Japan! It’s a spoof of British society,” is another defense. But it has been some 30 years since director Jonathan Miller stripped The Mikado of its faux Japanese veneer and made it quite obviously about the English, banishing the “orientalist” trappings from 100 years earlier. Besides, reviews of prior NY Gilbert & Sullivan Players productions note that the script is regularly updated with topical references germane to the present day, so claims to historical accuracy have already been tossed away.

Looking at the New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players (NYGASP) cast on their website, it appears that the company is almost exclusively white. While our increasingly multicultural society makes it difficult and reductive to assume race and ethnicity based on names and photos, I noted a single person who I would presume to be Latino among the 70 photos and bios, and seemingly no actors of Asian heritage. While I should allow for the possibility that there may be new company members to come, it seems clear that the preponderance of The Mikado company will be white.

Was it only a year ago that editorial pages and arts pages erupted over a production of The Mikado in Seattle precisely because of an all-white cast? Is it possible that in the insular world of Gilbert and Sullivan aficionados, word didn’t reach the founder and artistic director of NYGASP, Albert Bergeret? I doubt it. In Seattle, the uproar was sufficient to warrant a gathering of the arts community to air grievances and discuss the lack of racial and ethnic awareness shown by the Seattle troupe. That it followed on another West Coast controversy, a La Jolla Playhouse production of The Nightingale, a musical adaptation of a China-set Hans Christian Andersen tale that utilized “rainbow casting,” rather than ethnically specific casting, only added fuel to the justifiable controversy.

This year, The Wooster Group sparked protest on both coasts with its production of Cry Trojans, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida that had members of an all-white company in redface portraying Native Americans and appropriating Native American culture, as viewed through the wildly inaccurate prism of American western movies. Yet in a victory for ethnically accurate casting earlier this year, a major Texas theatre company recast its leading actor in The King and I when it was made abundantly clear by the Asian American theatre community that a white actor as the King of Siam simply wasn’t acceptable.

The NYGASP production of The Mikado (photo by William Reynolds)

That NYGASP will be performing on the NYU campus makes the impending production all the more surprising. It is highly doubtful that the university’s arts programs would undertake an all-white Mikado any more than they would do an all-white production of Porgy and Bess (although copyright probably prevents them from attempting the latter). College campuses are where racial consideration is at the forefront of thinking and action. Is it possible that The Mikado is in the Christmas to New Year’s slot precisely because school will not be in session and the university will be largely vacant, mitigating the potential for protest? Without school in session, NYGASP can’t even take advantage of the university community, if both parties agreed, to contextualize this production as part of a broader cultural conversation, not to explain it away, but to interrogate the many issues it raises.

“We can’t find qualified performers in the Asian-American community,” is another one of the frequent defenses of yellowface Mikados. After 25 years of countless productions of Miss Saigon, a revised Flower Drum Song with an entirely Asian-American cast, and two current Broadway productions (The King and I and the impending Allegiance) with largely Asian casts, it’s not possible to claim that the talent isn’t out there. Excuses about training or worse, diction (which is noted on the NYGASP site), are utterly implausible.

Admittedly, even with racially authentic casting, The Mikado is a problematic work, since it is rooted in ignorant stereotypes of Japan and not in any real truth. Does that make it unproducible, like, say The Octoroon (as explored by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s revisionist An Octoroon), or any number of early musical comedies which traded in now-offensive racial humor? No, as Jonathan Miller proved 30 years ago. And while it seems contradictory, even if the text and characterizations of The Mikado are retrograde, if it is to be done, at least it should be interpreted by Asian actors, who are afforded too little opportunity in theatre, musical theatre, operetta and opera as it is. There are any number of Asian performers who will discuss their reservations about Miss Saigon as well, but at least it affords them work, and the chance to bring some sense of nuance and authenticity to the piece. The same should be true of The Mikado.

The upset surrounding The Mikado at the Skirball Center has just begun to bubble up, originating so far as I saw with Facebook posts from Leah Nanako Winkler, Ming Peiffer, and Mike Lew; Winkler has already posted a blog in which she speaks candidly with NYGASP’s Bergeret and Erin Quill has a strong take as well. Hopefully a great deal more will be said, with the goal that instead of keeping The Mikado trapped in amber as G&S loyalists seem to prefer, it will be brought properly into the 21st century if it is to be performed at all. In a city as large as New York, maybe there are those who see six performances of The Mikado as being insignificant and not worthy of attention. But in a city as modern and multicultural as New York, can and should a yellowface, Causcasian Mikado be countenanced? Now is the time for the last (ny)gasp of clueless Mikados.

Update, September 16, 2 pm: NYGASP has replaced the home page of their website with a statement titled, “The Mikado in the 21st Century.” It reads in part:

Gilbert studied Japanese culture and even brought in Japanese acquaintances to advise the theater company on costumes, props and movements. In its formative years, NYGASP similarly engaged a Japanese advisor, the late Kayko Nakamura, to ensure that our costumes and sets remain true to the spirit of the culture that inspired them. We are dedicating this year’s production of The Mikado to her memory.

One hundred and forty years after the libretto was written, some of Gilbert’s Victorian words and attitudes are certainly outdated, but there is vastly more evidence that Gilbert intended the work to be respectful of the Japanese rather than belittling in any way. Although this is inevitably a subjective appraisal, we feel that NYGASP’s production of The Mikado is a tribute to both the genius of Gilbert and Sullivan and the universal humanity of the characters portrayed in Gilbert’s libretto.

In all of our productions, NYGASP strives to give the actors authentic costumes and evocative sets that capture the essence of a foreign or imaginary culture without caricaturing it in any demeaning or stereotypical way. Lyrics are occasional altered to update topical references and meet contemporary sensibilities; makeup and costumes are intended to be consistent with modern expectations.

Update, September 16, 4 pm: Since I made the original post yesterday, several other pertinent blog posts have appeared, and I wanted to share them as well. There are many aspects to this conversation.

From Ming Peiffer, “#SayNoToMikado: Here’s A Pretty Mess.”

From Melissa Hillman, “I Get To Be Racist Because Art: The Mikado.”

From Chris Peterson, “The Mikado Performed In Yellowface and Why It’s Not OK.”

From Barb Leung, “Breaking Down The Issues with ‘The Mikado’”

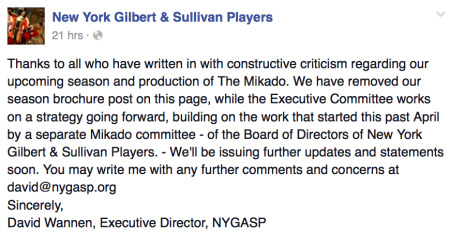

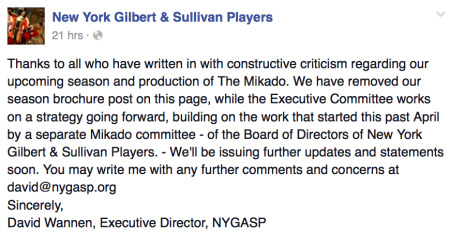

Update, September 17, 7 am: NYGASP has posted the following message on their Facebook page:

Update, September 18, 8 am: Overnight, NYGASP announced that they are canceling their production of The Mikado at the Skirball Center, replacing it with The Pirates of Penzance. A statement on their website reads as follows:

New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players announces that the production of The Mikado, planned for December 26, 2015-January 2, 2016, is cancelled. We are pleased to announce that The Pirates of Penzance will run in it’s place for 6 performances over the same dates.

NYGASP never intended to give offense and the company regrets the missed opportunity to responsively adapt this December. Our patrons can be sure we will contact them as soon as we are able, and answer any questions they may have.

We will now look to the future, focusing on how we can affect a production that is imaginative, smart, loyal to Gilbert and Sullivan’s beautiful words, music, and story, and that eliminates elements of performance practice that are offensive.

Thanks to all for the constructive criticism. We sincerely hope that the living legacy of Gilbert & Sullivan remains a source of joy for many generations to come.

David Wannen Executive Director New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players

Update, September 18, 3 pm: The NYGASP production of The Mikado was scheduled to be given a single performance on the campus of Washington and Lee University this coming Monday evening, September 21. As of this afternoon, the production has been replaced with the NYGASP production of The Pirates of Penzance.

* * *

Howard Sherman is the interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts.

September 4th, 2015 § § permalink

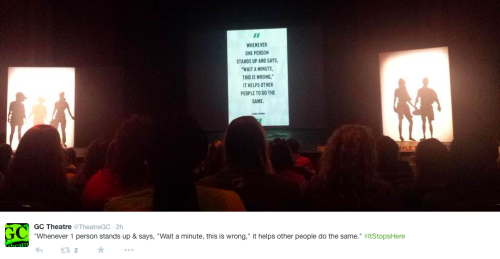

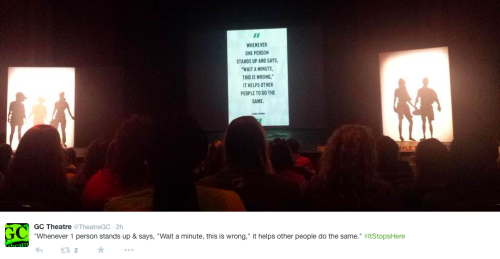

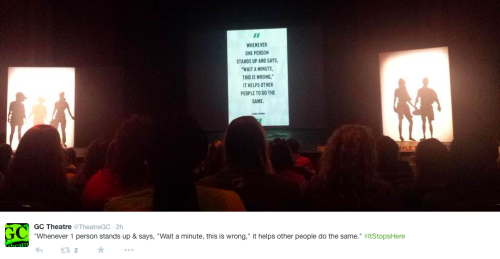

Poster from It Stops Here at Greensboro College

Members of the Greensboro College community have the right to be free from gender-based discrimination, sexual harassment, and sexual misconduct of any kind.

– from the Greensboro College Sexual Misconduct Policy

To start the new school year, Greensboro College in North Carolina required all of its first-year students to attend a performance of It Stops Here, a play about sexual violence, as part of the college’s newly adopted Sexual Misconduct policy. If that were all there was to report to illuminate how, beyond online training and in-person seminars, the school was employing theatre – a student written and directed play, no less – to confront this topic, it would be a terrific example of the power of theatre. Instead, the first performance of It Stops Here resulted in the harassment of the students performing the play and the opening of a Title IX investigation on the campus within 24 hours of that first presentation. It showed that even the dramatic rendering of sexual violence and its aftermath could provoke vocally insensitive, deeply offensive responses among first year students, and that despite the new steps taken by the school, many more were needed.

* * *

In presenting It Stops Here, a project of the college theatre department, it appears that the school’s primary concern was the potential to provoke deeply felt emotional responses in the audience. The play combined the words of the playwright with monologues from survivors of sexual assault that were submitted for use and presented verbatim. There were “trigger warnings” on the show’s promotional materials and an announcement prior to the performance; students acting as ushers were stationed in the aisles with flashlights to immediately assist any student who was overcome and needed to leave quickly.

The production had its first performance, a preview really, at 11 am on Wednesday morning this week, with students required to attend as part of their first-year seminar classes, an ongoing orientation program on how to succeed in college, as the school president described it. Teachers and coaches were to attend with their students, so that the show might provide the basis for further conversation.

“There was a certain segment of the audience that was joking and making crude remarks,” said Luke Powell, a senior theatre major who appears in the play. “One of the first things I noticed was during one of the monologues. One of the girls was doing hers and I could hear that this portion of the audience was catcalling her during this story of a rape victim. That really set me off, because it’s really disrespectful.

“The worst thing that happened,” Powell later said, “was when we get to the end of the play, the stage goes dark and four of the girls do the internal thoughts of a victim during a sexual attack. Some of that group got up to leave, not because they were triggered. Some of the group was saying stuff like ‘oh, you want it,’ and one started making a noise with his hands that sounded like masturbation throughout the five or six minute scene.”

“I expected this to happen,” declared Makenzie Degenhardt, a sophomore theatre major who appears in the play. “It’s a topic people don’t like to talk about. As soon as someone says rape, people get uncomfortable. People make jokes about things they’re uncomfortable with, but in this case it was inappropriate.”

Dagenhardt described hearing, “laughing and reactions that were not appropriate. People were laughing, clapping and encouraging behavior that shouldn’t be happening.” As to how the behavior affected her own performance, Dagenhardt said, “It made me speak louder. When I’m walking down the street and a boy catcalls me, I just ignore it, so I spoke louder to make sure I was heard. I was appalled.”

Dagenhardt said that her initial reaction was, “Oh, boys react like this, this is normal.” But upon reflection she realized, “It shouldn’t be normal. That’s what the point of the show is. If it happens again, I will respond differently.”

Another actor in the play, Emily Parker, a junior theatre major concentrating in musical theatre performance, described being on stage with a male scene partner. “A particular group of boys was talking rudely,” she said. They were talking loudly about how they didn’t want to be there and how they thought he [the male actor] was gay. Typical teenage boy stuff. “He’s so gay’.”

Ana Radulescu, a freshman theatre major concentrating in directing, who was the assistant director for the show, watched from the back of the house. She described the behavior of one pocket of students during the same scene that Dagenhardt referred to. “They did call him a ‘fag’,” she said. “He had a line that said ‘No one in high school ever told me I would have a girlfriend,’ and a bunch of people around me just started laughing.” Radulescu also described hearing a student, as a female actor was speaking on stage, speaking only partially in a whisper to those around him, say, “Whore. Bitch.”

Radulescu also said that another student, seated near where she stood at the back, before the show the show had even started, declaimed things like, “It was consensual – I didn’t rape her” and “I did Haven, I promise.” Haven is the online sexual harassment training all students were required to complete.

* * *

Of the five students who spoke on the record for this article, all of them expressed disappointment at the fact that while there were faculty in the theatre during the performance, they were unaware of any efforts by those faculty members to curtail the behavior that continued throughout the show. Several students spoke specifically about the lack of action by the Dean of Students, who they say was seated close to the area that harbored the worst offenders, and couldn’t have possibly missed what was happening. Some students also said that there was less faculty than anticipated, saying that not all of the instructors who were supposed to attend with the students, in order to facilitate subsequent discussion, had been present.

The students who were in the show all expressed, in differing ways, their own indecision about what to do in the face of inappropriate behavior and language. Emily Parker said, “We were in a predicament over whether to confront it or go on with the show.”

Backstage, Rebecca Hougas, a freshman theatre major concentrating in theatre education, was working as assistant stage manager, and said that for much of the play, she wasn’t aware of what was taking place, until late in the show.

“I could hear laughter,” she said, “and I knew this was not a laughing matter.” Hougas said that she really came to understand what was going on by seeing how the actors, who were onstage for most of the performance, reacted when they came offstage. “We had one actor come off the stage in tears over what she was trying to say.”

Several students spoke of actors being physically ill after the performance, and of the company coming together to support one another. Those I spoke with say they were upset upon leaving after the show, even as they had banded together to support one another, but not expecting any significant further fallout from the incident.

* * *

I first learned of what had happened at the performance of It Stops Here when, the next day, playwright and advocate Jacqueline Lawton sent me a Tumblr post recounting the event, written by Nicole Swofford, a recent graduate of Greensboro with a theatre degree who is still close with some of the students involved in the production. It described many of the same incidents that were ultimately described to me, but Swofford was also reporting what was said to her, as she hadn’t been at the show.

Swofford was very clear, and very honest, about her intent is posting, writing:

“Greensboro College is a small private college with less than 2,500 students and there hasn’t been a sexual assaulted recorded in the official report in years. Which is a blatant cover to protect the school from getting into to more hot water than it already is (having suffered from lots of financial problems in the past).

This is disgusting, and as a survivor of my own assault, and an alumni of this school I am appalled. All I can ask is that you share this story with everyone, and realize our fight is far from over.”

She had written on Wednesday evening, and her post, along with Facebook posts and comments about the incident, circulated quickly around the campus.

* * *

Where this story may differ from other accounts of sexual harassment on college campuses is that, less than 24 hours after the performance, the school opened a Title IX investigation. It did so on its own, not as a result of a specific complaint by a student, faculty or staff member. It is quite possible that this was because students reported Greensboro’s Title IX Coordinator, Emily Scott, as having been present at the performance. Her title at the school also includes “Assistant to the President.”

As information was being routed to me, but before I spoke directly with anyone on campus, a statement from the college president, Dr. Lawrence D. Czarda, addressed the issue in a school-wide communication:

“It has been reported that during a special performance Wednesday of the play “It Stops Here” for First Year Seminar classes, several audience members made comments that were offensive and sexual in nature. Under our new Sexual Misconduct policy, the comments that have been reported qualify as sexual harassment. The Title IX Coordinator has reviewed the reported comments and has asked the Title IX Investigator to gather additional information to determine who is responsible for making the comments. The college is pursuing a formal complaint of sexual misconduct against the students and is working to identify them. Upon results of the investigation, those found responsible will face disciplinary consequences.”

He also wrote:

“However, Wednesday’s incident makes clear that we as an academic and social community still have much to learn. That includes all of us, not just a few students. In addition to the Title IX investigation, the college will be reviewing and discussing the entirety of the context of the incident. Among many other questions, we will address such issues as what faculty and staff who were present might have done differently. Beyond meeting our legal obligations, the College’s goal is to make this incident a learning opportunity for the entire College community.”

When I spoke with Dr. Czarda, he volunteered that, “We do not have a history of sexual assaults on campus.” But he said that in response to the national dialogue about sexual violence, “the board adopted new policies which were put into place July 1. All students were required to take an online training course before the process of moving in. In addition, all students are required to do an on-site training program. All faculty and staff were required to do online and in-person training sessions. The fact that the student production is part of the required training means they’ve heard what these issues are about.”

When asked about what kind of preparation students had been given prior to seeing the play, he cited the online and in-person sexual misconduct training implemented by the school. “Did they know specifically what was going to happen on stage?” Dr. Czarda asked rhetorically, suggesting that they didn’t, that students attended the show without any direct contextual preparation prior to attending. But he said, “I think we did a tolerably good job in prepping the students.”

As to why no member of the faculty or staff intervened in light of the catcalling, insults and disruptions, Dr. Czarda said that was a “key question.” He said, “On the one hand, I have been told that there was some behavior that was not atypical of freshmen,” but he said, “I have not talked to any faculty or staff who heard the comments being made. I’m very troubled by that.” As to whether all faculty who we supposed to attend had done so, he said, “I hope that is not the case.”

Regarding steps being taken to insure that the incident would not recur, Dr. Czarda said that there would be campus security and faculty at every performance; he attended last night’s show. “We will have a very clear, immediate response,” he stated. “I would be totally disheartened and shocked if anything like this happened again.”

The students told me that they had agreed that if there were incidents at subsequent performances, they would simply pause in place until it ceased; some said they might direct their looks to where the believed the interruptions to have come from. Several, jokingly, invoked the name of Patti LuPone and her cellphone incident of earlier this summer.

Luke Powell subsequently reported that the Thursday evening performance had taken place without incident. “I’ve never seen an audience give a standing ovation so quickly,” he wrote.

* * *

As readers can tell from this account, some students who were a part of It Stops Here took me up on my offer to speak with them, others obviously did not, and I don’t think anyone should infer anything from the fact that I did not hear from some. That is their absolute right.

As readers can tell from this account, some students who were a part of It Stops Here took me up on my offer to speak with them, others obviously did not, and I don’t think anyone should infer anything from the fact that I did not hear from some. That is their absolute right.

Because institutionally, it is so often the case that in the midst of a crisis organizations initially go silent, trying to decide the best course of action, I have to say that Dr. Czarda’s willingness to speak with me within three hours of my request was both surprising and appreciated.

But I now want to say to Dr. Czarda something I didn’t express when I spoke with him, in part because by the time we spoke, he was getting organized to attend last night’s performance and had limited time. I want to say that while he may be technically correct when he says there is no history of sexual assaults on his campus, that does not mean there haven’t been sexual assaults on his campus, only that they have gone unreported, that they are not part of the school’s records.

Statistically, both on campuses and in the population nationally, sexual assault is too widespread to imagine that Greensboro is a unique sanctuary. Students up until now may have been too afraid, may have been too intimidated, may not have seen genuine evidence of support and understanding in the school environment, prompting them to keep silent. If the prevailing attitude is “it doesn’t happen here” and if the new guidelines have been put in place only to comply with general practice and to insulate the school from future liability, not because of a deep understanding of the prevalence of sexual violence, then there is still a great deal more learning to be done, and not just by the students of Greensboro.

The students I spoke with were uniformly appreciative and indeed surprised by the speed with which the school began its investigation. However, several expressed concern that because the perpetrators sat in the dark and were not immediately discovered and taken out, no one will ever be held accountable. Greensboro College is now on the line both in terms of how it addresses this current situation and what it does now that it has learned that its newly implemented policies are clearly insufficient.

I would also be remiss if I didn’t say to Dr. Czarda and the Greensboro faculty that the students are not only concerned about getting through the performances this weekend. While one noted that they feel “more comfortable knowing that some of the faculty is stepping up and doing their job” and that “the regulations are going to make sure this doesn’t get swept under the rug,” there are now students on your campus who are concerned about recriminations and retaliation because they spoke up, because they spoke out. Beyond insuring the performances go forward smoothly, beyond investigating what took place on Wednesday, you now must do everything possible to make certain that all students connected with this production, and indeed all students (and faculty and staff) are safe and secure on your campus, in the days, weeks and months to come.

What happens at Greensboro in the wake of this incident is not simply a campus matter, but one with impact on every college campus, and for every survivor of sexual assault and their families and friends. If this is what happens when sexual assault is portrayed, what will happen if – and indeed, sadly, when – sexual violence occurs? The school has already been made an example. Now it must demonstrate whether it can set one.

* * *

When asked whether they thought that the rest of the audience at Wednesday’s performance had gotten the message of the show, several of the students professed somewhat ruefully that they didn’t know; one said she knew of one student who had expressly communicated how important it had been for her. If the remaining three performances go as well as last night’s did, then hopefully the message of the play will be reaching many more members of the Greensboro College community in the way it was intended to do.

At the conclusion of our conversation, Ana Radulescu summed up so much of what is essential now in regards to Greensboro and It Stops Here.

“We all now understand what those girls who sent us those monologues were talking about. In a way, we were all sexually harassed yesterday and this Title IX report says so. I never knew that through theatre someone could be harassed. Now in six hours, I understand a lot more of what comes out of those girls’ mouths.

“The idea of this piece is to start this conversation. I don’t think we planned on it starting this way. But if you want to look at it, it’s nothing different than what we meant it to do. The fact that it’s not getting ignored is sort of amazing. It has reaffirmed for us that the piece needs to happen, why it needs to happen and why it needs to happen here. If anyone questioned that, well – we have the answer.”

Update, September 5: A local television newscast covered the incident at Greensboro College last night. You can view their report here; the video piece is more complete than the accompanying text.

The title of the play discussed in this post is shown on the poster as “It Stops Here” with a period at the end of Here. The punctuation mark has been omitted from the text for clarity.

I attempted to reach the theatre department chair David Schram and Josephine Hull, assistant professor of acting and voice, but neither replied to my inquiries.

This post will be amended and updated as the situation warrants.

Howard Sherman is the director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School for Performing Arts.

September 4th, 2015 § § permalink

Members of the Greensboro College community have the right to be free from gender-based discrimination, sexual harassment, and sexual misconduct of any kind.

– from the Greensboro College Sexual Misconduct Policy

To start the new school year, Greensboro College in North Carolina required all of its first-year students to attend a performance of It Stops Here, a play about sexual violence, as part of the college’s newly adopted Sexual Misconduct policy. If that were all there was to report to illuminate how, beyond online training and in-person seminars, the school was employing theatre – a student written and directed play, no less – to confront this topic, it would be a terrific example of the power of theatre. Instead, the first performance of It Stops Here resulted in the harassment of the students performing the play and the opening of a Title IX investigation on the campus within 24 hours of that first presentation. It showed that even the dramatic rendering of sexual violence and its aftermath could provoke vocally insensitive, deeply offensive responses among first year students, and that despite the new steps taken by the school, many more were needed.

* * *

In presenting It Stops Here, a project of the college theatre department, it appears that the school’s primary concern was the potential to provoke deeply felt emotional responses in the audience. The play combined the words of the playwright with monologues from survivors of sexual assault that were submitted for use and presented verbatim. There were “trigger warnings” on the show’s promotional materials and an announcement prior to the performance; students acting as ushers were stationed in the aisles with flashlights to immediately assist any student who was overcome and needed to leave quickly.

The production had its first performance, a preview really, at 11 am on Wednesday morning this week, with students required to attend as part of their first-year seminar classes, an ongoing orientation program on how to succeed in college, as the school president described it. Teachers and coaches were to attend with their students, so that the show might provide the basis for further conversation.

“There was a certain segment of the audience that was joking and making crude remarks,” said Luke Powell, a senior theatre major who appears in the play. “One of the first things I noticed was during one of the monologues. One of the girls was doing hers and I could hear that this portion of the audience was catcalling her during this story of a rape victim. That really set me off, because it’s really disrespectful.

“The worst thing that happened,” Powell later said, “was when we get to the end of the play, the stage goes dark and four of the girls do the internal thoughts of a victim during a sexual attack. Some of that group got up to leave, not because they were triggered. Some of the group was saying stuff like ‘oh, you want it,’ and one started making a noise with his hands that sounded like masturbation throughout the five or six minute scene.”

“I expected this to happen,” declared Makenzie Degenhardt, a sophomore theatre major who appears in the play. “It’s a topic people don’t like to talk about. As soon as someone says rape, people get uncomfortable. People make jokes about things they’re uncomfortable with, but in this case it was inappropriate.”

Dagenhardt described hearing, “laughing and reactions that were not appropriate. People were laughing, clapping and encouraging behavior that shouldn’t be happening.” As to how the behavior affected her own performance, Dagenhardt said, “It made me speak louder. When I’m walking down the street and a boy catcalls me, I just ignore it, so I spoke louder to make sure I was heard. I was appalled.”

Dagenhardt said that her initial reaction was, “Oh, boys react like this, this is normal.” But upon reflection she realized, “It shouldn’t be normal. That’s what the point of the show is. If it happens again, I will respond differently.”

Another actor in the play, Emily Parker, a junior theatre major concentrating in musical theatre performance, described being on stage with a male scene partner. “A particular group of boys was talking rudely,” she said. They were talking loudly about how they didn’t want to be there and how they thought he [the male actor] was gay. Typical teenage boy stuff. “He’s so gay’.”

Ana Radulescu, a freshman theatre major concentrating in directing, who was the assistant director for the show, watched from the back of the house. She described the behavior of one pocket of students during the same scene that Dagenhardt referred to. “They did call him a ‘fag’,” she said. “He had a line that said ‘No one in high school ever told me I would have a girlfriend,’ and a bunch of people around me just started laughing.” Radulescu also described hearing a student, as a female actor was speaking on stage, speaking only partially in a whisper to those around him, say, “Whore. Bitch.”

Radulescu also said that another student, seated near where she stood at the back, before the show the show had even started, declaimed things like, “It was consensual – I didn’t rape her” and “I did Haven, I promise.” Haven is the online sexual harassment training all students were required to complete.

* * *

Of the five students who spoke on the record for this article, all of them expressed disappointment at the fact that while there were faculty in the theatre during the performance, they were unaware of any efforts by those faculty members to curtail the behavior that continued throughout the show. Several students spoke specifically about the lack of action by the Dean of Students, who they say was seated close to the area that harbored the worst offenders, and couldn’t have possibly missed what was happening. Some students also said that there was less faculty than anticipated, saying that not all of the instructors who were supposed to attend with the students, in order to facilitate subsequent discussion, had been present.

The students who were in the show all expressed, in differing ways, their own indecision about what to do in the face of inappropriate behavior and language. Emily Parker said, “We were in a predicament over whether to confront it or go on with the show.”

Backstage, Rebecca Hougas, a freshman theatre major concentrating in theatre education, was working as assistant stage manager, and said that for much of the play, she wasn’t aware of what was taking place, until late in the show.

“I could hear laughter,” she said, “and I knew this was not a laughing matter.” Hougas said that she really came to understand what was going on by seeing how the actors, who were onstage for most of the performance, reacted when they came offstage. “We had one actor come off the stage in tears over what she was trying to say.”

Several students spoke of actors being physically ill after the performance, and of the company coming together to support one another. Those I spoke with say they were upset upon leaving after the show, even as they had banded together to support one another, but not expecting any significant further fallout from the incident.

* * *

I first learned of what had happened at the performance of It Stops Here when, the next day, playwright and advocate Jacqueline Lawton sent me a Tumblr post recounting the event, written by Nicole Swofford, a recent graduate of Greensboro with a theatre degree who is still close with some of the students involved in the production. It described many of the same incidents that were ultimately described to me, but Swofford was also reporting what was said to her, as she hadn’t been at the show.

Swofford was very clear, and very honest, about her intent is posting, writing:

“Greensboro College is a small private college with less than 2,500 students and there hasn’t been a sexual assaulted recorded in the official report in years. Which is a blatant cover to protect the school from getting into to more hot water than it already is (having suffered from lots of financial problems in the past).

This is disgusting, and as a survivor of my own assault, and an alumni of this school I am appalled. All I can ask is that you share this story with everyone, and realize our fight is far from over.”

She had written on Wednesday evening, and her post, along with Facebook posts and comments about the incident, circulated quickly around the campus.

* * *

Where this story may differ from other accounts of sexual harassment on college campuses is that, less than 24 hours after the performance, the school opened a Title IX investigation. It did so on its own, not as a result of a specific complaint by a student, faculty or staff member. It is quite possible that this was because students reported Greensboro’s Title IX Coordinator, Emily Scott, as having been present at the performance. Her title at the school also includes “Assistant to the President.”

As information was being routed to me, but before I spoke directly with anyone on campus, a statement from the college president, Dr. Lawrence D. Czarda, addressed the issue in a school-wide communication:

“It has been reported that during a special performance Wednesday of the play “It Stops Here” for First Year Seminar classes, several audience members made comments that were offensive and sexual in nature. Under our new Sexual Misconduct policy, the comments that have been reported qualify as sexual harassment. The Title IX Coordinator has reviewed the reported comments and has asked the Title IX Investigator to gather additional information to determine who is responsible for making the comments. The college is pursuing a formal complaint of sexual misconduct against the students and is working to identify them. Upon results of the investigation, those found responsible will face disciplinary consequences.”

He also wrote:

“However, Wednesday’s incident makes clear that we as an academic and social community still have much to learn. That includes all of us, not just a few students. In addition to the Title IX investigation, the college will be reviewing and discussing the entirety of the context of the incident. Among many other questions, we will address such issues as what faculty and staff who were present might have done differently. Beyond meeting our legal obligations, the College’s goal is to make this incident a learning opportunity for the entire College community.”

When I spoke with Dr. Czarda, he volunteered that, “We do not have a history of sexual assaults on campus.” But he said that in response to the national dialogue about sexual violence, “the board adopted new policies which were put into place July 1. All students were required to take an online training course before the process of moving in. In addition, all students are required to do an on-site training program. All faculty and staff were required to do online and in-person training sessions. The fact that the student production is part of the required training means they’ve heard what these issues are about.”

When asked about what kind of preparation students had been given prior to seeing the play, he cited the online and in-person sexual misconduct training implemented by the school. “Did they know specifically what was going to happen on stage?” Dr. Czarda asked rhetorically, suggesting that they didn’t, that students attended the show without any direct contextual preparation prior to attending. But he said, “I think we did a tolerably good job in prepping the students.”

As to why no member of the faculty or staff intervened in light of the catcalling, insults and disruptions, Dr. Czarda said that was a “key question.” He said, “On the one hand, I have been told that there was some behavior that was not atypical of freshmen,” but he said, “I have not talked to any faculty or staff who heard the comments being made. I’m very troubled by that.” As to whether all faculty who we supposed to attend had done so, he said, “I hope that is not the case.”

Regarding steps being taken to insure that the incident would not recur, Dr. Czarda said that there would be campus security and faculty at every performance; he attended last night’s show. “We will have a very clear, immediate response,” he stated. “I would be totally disheartened and shocked if anything like this happened again.”

The students told me that they had agreed that if there were incidents at subsequent performances, they would simply pause in place until it ceased; some said they might direct their looks to where the believed the interruptions to have come from. Several, jokingly, invoked the name of Patti LuPone and her cellphone incident of earlier this summer.

Luke Powell subsequently reported that the Thursday evening performance had taken place without incident. “I’ve never seen an audience give a standing ovation so quickly,” he wrote.

* * *

As readers can tell from this account, some students who were a part of It Stops Here took me up on my offer to speak with them, others obviously did not, and I don’t think anyone should infer anything from the fact that I did not hear from some. That is their absolute right.

As readers can tell from this account, some students who were a part of It Stops Here took me up on my offer to speak with them, others obviously did not, and I don’t think anyone should infer anything from the fact that I did not hear from some. That is their absolute right.

Because institutionally, it is so often the case that in the midst of a crisis organizations initially go silent, trying to decide the best course of action, I have to say that Dr. Czarda’s willingness to speak with me within three hours of my request was both surprising and appreciated.

But I now want to say to Dr. Czarda something I didn’t express when I spoke with him, in part because by the time we spoke, he was getting organized to attend last night’s performance and had limited time. I want to say that while he may be technically correct when he says there is no history of sexual assaults on his campus, that does not mean there haven’t been sexual assaults on his campus, only that they have gone unreported, that they are not part of the school’s records.

Statistically, both on campuses and in the population nationally, sexual assault is too widespread to imagine that Greensboro is a unique sanctuary. Students up until now may have been too afraid, may have been too intimidated, may not have seen genuine evidence of support and understanding in the school environment, prompting them to keep silent. If the prevailing attitude is “it doesn’t happen here” and if the new guidelines have been put in place only to comply with general practice and to insulate the school from future liability, not because of a deep understanding of the prevalence of sexual violence, then there is still a great deal more learning to be done, and not just by the students of Greensboro.

The students I spoke with were uniformly appreciative and indeed surprised by the speed with which the school began its investigation. However, several expressed concern that because the perpetrators sat in the dark and were not immediately discovered and taken out, no one will ever be held accountable. Greensboro College is now on the line both in terms of how it addresses this current situation and what it does now that it has learned that its newly implemented policies are clearly insufficient.

I would also be remiss if I didn’t say to Dr. Czarda and the Greensboro faculty that the students are not only concerned about getting through the performances this weekend. While one noted that they feel “more comfortable knowing that some of the faculty is stepping up and doing their job” and that “the regulations are going to make sure this doesn’t get swept under the rug,” there are now students on your campus who are concerned about recriminations and retaliation because they spoke up, because they spoke out. Beyond insuring the performances go forward smoothly, beyond investigating what took place on Wednesday, you now must do everything possible to make certain that all students connected with this production, and indeed all students (and faculty and staff) are safe and secure on your campus, in the days, weeks and months to come.

What happens at Greensboro in the wake of this incident is not simply a campus matter, but one with impact on every college campus, and for every survivor of sexual assault and their families and friends. If this is what happens when sexual assault is portrayed, what will happen if – and indeed, sadly, when – sexual violence occurs? The school has already been made an example. Now it must demonstrate whether it can set one.

* * *

When asked whether they thought that the rest of the audience at Wednesday’s performance had gotten the message of the show, several of the students professed somewhat ruefully that they didn’t know; one said she knew of one student who had expressly communicated how important it had been for her. If the remaining three performances go as well as last night’s did, then hopefully the message of the play will be reaching many more members of the Greensboro College community in the way it was intended to do.

At the conclusion of our conversation, Ana Radulescu summed up so much of what is essential now in regards to Greensboro and It Stops Here.

“We all now understand what those girls who sent us those monologues were talking about. In a way, we were all sexually harassed yesterday and this Title IX report says so. I never knew that through theatre someone could be harassed. Now in six hours, I understand a lot more of what comes out of those girls’ mouths.

“The idea of this piece is to start this conversation. I don’t think we planned on it starting this way. But if you want to look at it, it’s nothing different than what we meant it to do. The fact that it’s not getting ignored is sort of amazing. It has reaffirmed for us that the piece needs to happen, why it needs to happen and why it needs to happen here. If anyone questioned that, well – we have the answer.”

Update, September 5: A local television newscast covered the incident at Greensboro College last night. You can view their report here; the video piece is more complete than the accompanying text.

The title of the play discussed in this post is shown on the poster as “It Stops Here” with a period at the end of Here. The punctuation mark has been omitted from the text for clarity.

I attempted to reach the theatre department chair David Schram and Josephine Hull, assistant professor of acting and voice, but neither replied to my inquiries.

This post will be amended and updated as the situation warrants.

Please note: I afford all people the opportunity for healthy debate in the comments section of all of my blog posts, but I will not condone statements which advocate violence, racism or are in and of themselves verbal attacks. That is in no way an abridgment of anyone’s First Amendment rights; this is my right as the author and manager of this site. I will not exercise the removal of comments indiscriminately, but it is at my sole discretion.

Howard Sherman is the director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School for Performing Arts.