September 27th, 2013 § § permalink

The 2012 NEA SSPA Report

If yesterday’s news that theatre attendance is down more precipitously than any of the arts caused you to spit out your coffee over breakfast, well that’s probably because you haven’t been paying attention. To be fair, I suspect a lot of people haven’t been, with virtually every discussion of the performing arts in since 2008 having been prefaced with either “in these challenging times” or “since the financial meltdown of 2008.” But the time for qualifiers and excuses is clearly past, especially as every news report on American life in general seems to invoke the fairly recent cliché “the new normal.” Things have changed. Things are changing. Things will change. The arts need to change.

In citing slides of 9% for musical theatre and 12% for non-musicals over the past five years, and even more pronounced numbers over a longer range, the picture painted by the NEA shows an overall decline in arts attendance, with theatre hardest hit. Coming just days after some co-mingled summary numbers from an Americans for the Arts report suggested theatre might be looking up, it was certainly startling news. But a closer look at the latter study actually confirms the reported NEA trend.

Looking elsewhere, the same picture appears. The last Theatre Communications Group “Theatre Facts” report, covering results from 2008 to 2012, shows a 1.8% decline in attendance in the portion of their membership studied – not as pronounced as the NEA figures, but certainly heading the wrong way as well. It’s also important to remember that as expansive as it is, TCG itself is only a subset of overall US theatres. In a more easily defined theatrical realm of activity, Broadway in the same period shows a 5% audience decline, with a 17% increase in income, suggesting an increasingly inaccessible theatrical realm, and an economic model that will only further stratify audiences.

The Ticketmaster UK Report

The only encouragement that one might wish to cling to is a report from Ticketmaster’s analytics division, which shows stunningly positive stats about arts participation by younger audiences (including a snappy infographic). While it hints that there might be some lessons to be learned, we’d have to go to England to get them, because the study is entitled State of Play: Theatre UK. While it does include some US audience members (as well as a selection from Ireland, Germany and Australia), the US sample represents only 13% of the total, with 65% from the UK. Also, under theatre, Ticketmaster has folded in opera and dance, so it’s not a true apples to apples comparison.

Now I am one of the many who believes that theatre as a discipline will manage to survive the onslaught of electronic entertainment precisely because it is live and fundamentally irreproducible. We may be a niche, but there will always be those who treasure being in the same room with artists as art is created; I have often joked that theatre will only be in real danger when Star Trek: TNG’s holodeck becomes reality. Even these reports don’t sway me from that conceptual position. But I’m not sticking my head in the sand either.

Appreciation of the arts is, for many, something that is learned in childhood – namely in schools. Yet we only have to read about the state of public education to know that resources are diminished, anything that isn’t testable is expendable, and fewer students are being exposed to arts education than they were years ago. Citing the 2008 NEA SSPA report: “In 1982, nearly two-thirds of 18-year-olds reported taking art classes in their childhood. By 2008, that share had dropped below one-half, a decline of 23 percent.” In less than 30 years, inculcation in the arts through the schools declined notably, so is it any wonder that we’re seeing declines in arts participation over time?

In a 2012 Department of Education study, it was reported that “the percentages of schools making [music and visual arts] available went from 20 percent 10 years ago to only 4 and 3 percent, respectively, in the 2009-10 school year. In addition, at more than 40 percent of secondary schools, coursework in arts was not required for graduation in the 2009-10 school year.” That’s all the more reason to be concerned. Certainly many arts organizations have committed to working with or in schools, but are the programs comprehensive enough? We’ve become ever more sophisticated in how to create truly in-depth, ongoing education experiences, but perhaps in doing so, we’re reaching fewer students. Maybe we have to look at how to restore sheer numbers as part of that equation, while maintaining quality, to insure our own future.

Art from Americans for the Arts report

It’s time to make an important distinction. As I said, I believe ‘theatre’ will survive for years to come. Where we would do well to focus immediate attention is on our ‘theatres,’ our companies. On a micro basis, it may be easy to shrug off declines, especially if you happen to be affiliated with a company that is bucking the trend. But these reports with their macro view should take each and every theatre maker and theatre patron outside of the specifics of their direct experience to look at the field, not simply year to year, but over time. It suggests that there is a steady erosion in the theatergoing base, which hasn’t necessarily found a new level; just as a rising tide floats all boats, eventually our toys lie at the bottom of the tub once the drain is opened.

I don’t have the foresight to know where this will lead. One direction is that of Broadway, where the consistently risky business model favors shows that are built for the truly long run, but only for the select audiences with the resources to support ever increasing prices. Might that be mirrored in the not-for-profit community as well, with only the largest and most established companies able to secure audiences and funding if resources and interest truly diminish? Or might we see a shift away from institutions and edifices and towards more grass roots companies, where simpler theatre at lower prices and more basic production values finds the favor of those who still harbor an appetite for live drama?

I’ll make a prediction. While in the first half of my life I watched the bourgeoning of the resident theatre movement, which in turn seeded the growth of countless smaller local companies, my later years will see a contraction in overall production at the professional level; it’s already begun, as a few companies seem to go under every year and have been for some time. That means that it will become ever harder for people to make their lives in theatre, because there will be fewer job opportunities for them.

Since I’ve already employed science fiction in my argument, let me turn to it again. We’ve all seen or read stories where someone goes back in time to right some past wrong (and for the moment, let’s forget that they often as not ruin the future in the process). Is there a point where we could or should make some fundamental change in how theatre functions – not as an art, but as an industry? Is there a single watershed moment where one choice determined the course of the field that some future time traveler could set right? I suspect not, unless we were talking about preventing (in succession) the discovery of electricity, the invention of TV and movies, or the creation of the internet.

That’s why we have to shift the paradigm now, and not just worry about selling tickets to the current show or meeting next year’s budget, but focus on what’s truly sustainable in 10, 25 or 50 years time. This week’s data barrage shows one thing we mustn’t ignore: even if we can’t see it in our own day to day experience, what we’re doing now isn’t working and the tide is going out.

My thanks to Mariah MacCarthy, who brought the 2008 NEA SSPA Report summary and the 2012 Department of Education report to my attention.

September 26th, 2013 § § permalink

If you’ve been reading The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times this week, attempting to find out how the arts as a whole are doing, you would likely get a fairly consistent picture coming from the efforts of those two sources, and it doesn’t bode well for the arts in America. But if your focus happens to be on theatre, your head might spin from seeming conflicts.

On Monday, September 23, in The Los Angeles Times, Mike Boehm reported the Americans for the Arts just issued National Arts Index of arts participation, complete through 2011. He wrote, using their executive summary, “The report noted ‘overall increases’ in theater and symphony attendance in 2011, and drops for opera and movies.” Good news for the theatre crowd, right?

Well this morning, Patricia Cohen, writing in The New York Times about the National Endowment for the Arts newly released “Highlights from the 2012 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts,” made the startling statement that “theater is the artistic discipline in America that is losing audience share at the fastest rate in recent years.” Scary, no?

So the question is, are these reports in conflict? Is there some underlying difference in methodology that has yielded markedly different results? Is it because the Americans for the Arts report is only through 2011, while the National Endowment for the Arts report is through 2012?

Much as I’d like to tell you that things are not as negative as the New York Times story makes it seem, the discrepancy is in fact due largely to aggregation of disciplines on the Americans for the Arts summary, while the NEA report keeps each art form distinct – as does the full text of the Americans for the Arts study. The rosier picture Boehm drew from Americans for the Arts emerged because it merges theatre with symphony and opera and, perhaps to the surprise of many, the latter disciplines had a very good year in 2011.

From the Americans for the Arts Report

Symphony and opera attendance increased by almost 3 million from 2010 to 2011, while theatre attendance was down by about 300,000 in the same period. So in merging, the loss in theatre is masked by the jump in symphony and opera. The discrete numbers in the NEA report, sampled in 2002, 2008 and 2012, show an ongoing decline for theatre, with the rate of change for musicals at -9% and the rate of change for plays at -12%. This mirrors an aggregate decline from 50 million to 45.2 million theatre patrons over the period from 2003 to 2011, as shown by Americans for the Arts.

From the National Endowment for the Arts report

So while summaries may indicate that there’s some upside for theatre, the detail of the reports are quite clear: theatergoing is trending down. If there’s another comprehensive report that actually challenges this data, it would be good to see it, but if the combined results from these two central representatives and supporters of the arts in America have yielded comparable results, the wake up call for theatre cannot be sounded any more loudly and clearly. No one should cling to shreds seemingly offered in a part of one study. To be sure, theatre’s overall attendance numbers far outpace symphony, opera and dance combined, but the trend doesn’t look good at all. And with arts attendance/participation in general decline, can theatre collectively get its act together to stop the bleeding, let alone reverse course?

I urge anyone working in the arts, in any discipline, to study both of these reports carefully. By all means, get beyond summaries and condensations. I’ve only focused on a few pages and I’m quite certain we’ve got a lot more to learn if we’re going to be able to generate good news about the field again and continue to make the case for the vitality and centrality of the arts in American life.

P.S. When a government agency and an advocacy group agree about the problems in American arts, wouldn’t it be nice if our president cared enough to even nominate someone to run the Endowment? The clock keeps ticking, but that’s the only sound we hear.

September 23rd, 2013 § § permalink

I have a confession to make: I am constitutionally unable to watch the acclaimed TV series Friday Night Lights. Now I realize this may be surprising to those who know and admire that program. My inability to sit through more than the first three episodes of season one is actually a testament to its effectiveness. The reason I cannot watch it is that it makes me profoundly angry.

The source of my anger is the omnipresence of the town’s obsession with football, which seems to be the only source of entertainment and focus for the Texan characters. I know the series is fiction (though drawn from Buzz Bissinger’s non-fiction book), but the single-minded portrayal of small-minded adults consumed by high school sports is by no means a false portrait in many communities, and it infuriates me. After all, I neither play sports nor follow any with particular interest. Where, I’ve always wanted to know, is the comparable enthusiasm for the arts in high schools, outside of magnet programs dedicated to them?

The source of my anger is the omnipresence of the town’s obsession with football, which seems to be the only source of entertainment and focus for the Texan characters. I know the series is fiction (though drawn from Buzz Bissinger’s non-fiction book), but the single-minded portrayal of small-minded adults consumed by high school sports is by no means a false portrait in many communities, and it infuriates me. After all, I neither play sports nor follow any with particular interest. Where, I’ve always wanted to know, is the comparable enthusiasm for the arts in high schools, outside of magnet programs dedicated to them?

Well, per Michael Sokolove’s account in his book Drama High (Riverhead Books, $27.95), such support exists in Levittown, Pennsylvania, at Truman High School. Sokolove paints a highly appealing portrait of a school where the drama club stands alongside sports in the pantheon of school activities, and some athletes even defect from their teams to perform on the Truman stage. He credits this achievement to the just retired teacher and director Lou Volpe, who over 44 years drew attention and respect to the theatre program in an underachieving district in a moderate-income community, not in some well-financed suburban setting. For those who recall a New York Times story about $100,000+ high school productions, this school and its program are worlds away.

I had many reactions as I read Sokolove’s book, but first among was them was pleasure at seeing the story of high school theatre well-told, especially its ability to sustain young people who need to be rooted in a supportive community in a way their home lives don’t necessarily offer (as was surely the case for some of my high school drama comrades). While there have been a number of low-budget film documentaries in recent years that have looked at high school and community theatre programs for youth (including an episode of TV’s 20/20 which shares a title with this volume), Drama High is the first high profile, in-depth book on the subject that I’ve come across. As such, it immediately becomes required reading: for young people who can learn more about the challenge and rewards of theatre, for parents who may well need the same background, for anyone who doubts the value of theatre as an educational and character-building activity not only for those who would become professionals, for those who want to spark reveries of their own experiences in high school drama.

The book is at its strongest in its first half, which chronicles Volpe’s production of Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa’s Good Boys and True, decidedly challenging work to take on at the high school level. In following the production, Sokolove really gets into the lives and heads of the kids who participate in the production and it evokes the profound importance and connectedness that theatre can bring, just like a spot on any sports team. That the play, which turns on matters of sexual orientation, can be staged in a public high school is a rebuke to small minded communities that seek to censor or eliminate drama programs over content – I’m looking at you Everett, Massachusetts and you Ottumwa, Iowa – as proxies for far too many more. That its achievements are recognized through regional and national Thespian Society competitions is icing on the cake, mirroring the plotting of Glee which focused on “making it to Nationals.” But this is real.

Friday Night Lights, also high school drama

The Glee comparison is one made in advance materials for the book (as is the Friday Night Lights connection), but unlike the Ryan Murphy TV series, Drama High never stoops to low and even ugly comedy and stereotype. Imagine if all of Glee sustained the level of quality and heart that characterized the story lines between Kurt and his dad, and you’ll get a closer approximation of what Drama High achieves.

The book is not without its drawbacks. As a graduate of Truman, Sokolove’s decision to write as a returning alumnus and ever-present observer draws attention to himself and away from straight reportage; his admiration for Volpe’s achievements is palpable, but as a result, we spend some time with Sokolove and Volpe instead of staying completely with Volpe and his kids, which is where the most compelling story lies. Also, as someone who is seemingly not immersed in the theatre (not necessarily a bad thing for a journalistic undertaking about theatre), Sokolove is drawn to Truman’s use by Music Theater International as a test site for musicals about to be launched into the high school realm, which is more about business and less about people. That Cameron Mackintosh went to Truman to see their Les Misérables is impressive, and a feather in Volpe’s cap, but it’s not moving; the same focus on external affirmation undermines the account of Truman’s pilot production of Spring Awakening.

At one point in the book, Sokolove quotes Volpe at length talking about his own evolution as a director and teacher: “I had to learn balance, harmony, order, design, composition.” Most any theatre nerd would recognize the phrase as being drawn, almost word for word, from Sondheim’s Sunday In The Park With George; Sokolove lets it pass unremarked. He also doesn’t seem to understand that when Volpe talks about changing the order of scenes in Good Boys and True, he’s actually considering violating of the licensing agreement for the play; as it happens, Volpe was talked out of the idea.

Glee at its best

What I missed most in Drama High was the detail of exactly how Truman High School’s drama program managed to achieve such primacy. Sokolove attributes it all to Volpe, and no doubt he was absolutely central. But because Sokolove knew Volpe relatively early in his tenure, and then returns to him in the final years, we don’t have a fully rounded account of how this once-married, now openly gay man forged a respect for a program that most schools treat as an afterthought. Was it nothing more than perseverance? I yearned for a road map that other teachers and districts might follow to correct the lopsidedness that has always upset me when comparing academic arts pursuits with sports.

But there is no denying that Drama High is a moving account of how the arts can profoundly change lives and even the outlook of a community. Even by mentioning that I was reading the book, and tweeting links to a New York Times Magazine excerpt, I heard back from people who live or have lived in or near Levittown, who spoke with enthusiasm of Volpe and his program, affirming Sokolove’s view. He has fashioned a rare tribute to an influential teacher; while I suspect that perhaps few districts may have come to appreciate drama in the way they have in Levittown, I am certain there are countless other teachers, not only of the arts, but of math, science, history and yes, athletics, who have had significant impact on scores of lives who are deserving of commemoration as well.

And of course, Drama High actually manages to suggest its own sequel. Will the drama program continue to thrive with Volpe gone? Will the ongoing cuts to “non-essential” school programs take its toll in Levittown now that the revered advocate has retired? Or after generations of residents coming to appreciate theatre, is it safe, at least for the foreseeable future? That’s another story to be told, of import to arts education programs everywhere, one sure to be of high drama.

September 19th, 2013 § § permalink

“Stanley? Is that you?”

A very good friend of mine began a successful tenure as the p.r. director of the Long Wharf Theatre in 1986, one year after I’d taken up the comparable position at Hartford Stage. He came blazing out of the gate with a barrage of stories and features in the first few months he was there. But as their third play approached, he called me for some peer-to-peer counseling. With a worried tone, he said, “Howard, my first show was All My Sons with Ralph Waite of The Waltons. My second show was Camille with Kathleen Turner. Now I’ve just got a new play by an unknown author without any stars in it. What do I do?”

My reply: “Welcome to regional theatre.”

Now as that anecdote makes clear, famous names are hardly new in regional theatre, though they’re somewhat infrequent in most cases. In my home state of Connecticut, Katharine Hepburn was a mainstay at the American Shakespeare Theatre in the 1950s, a now closed venue where I saw Christopher Walken as Hamlet in the early 80s. The venerable Westport Country Playhouse ran for many years with stars of Broadway and later TV coming through regularly; when I worked there in the 1984 and 1985 seasons, shows featured everyone from Geraldine Page and Sandy Dennis to David McCallum and Jeff Conaway. I went to town promoting Richard Thomas as Hamlet in 1987 at Hartford. The examples are endless.

So I should hardly be surprised when, in the past week, I have seen a barrage of coverage of Yale Repertory Theatre’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire with True Blood’s Joe Manganiello, or Joan Allen’s return to Steppenwolf, for the first time in two decades, in The Wheel. Indeed, I make the assumption, even the assertion, that they were cast because they were ideal for their roles, not out of any craven attempt to boost box office (Manganiello has even played the role on stage before, and of course Allen is a Steppenwolf veteran). I truly hope they both have great successes. But the stories are coming fast and furious (here’s an Associated Press piece on Allen and an “In Performance” video with Manganiello from The New York Times).

I have to admit, what once seemed a rare and wonderful opportunity to me as a youthful press agent gives me pause as a middle-aged surveyor of the arts scene. Perhaps it’s the proliferation of outlets that make these star appearances in regional theatre seem more heightened, with more attention when they happen. And that’s surely coupled with my ongoing fears about where regional arts coverage fits in today’s entertainment media priorities, which by any account are celebrity driven.

At a time when Broadway is portrayed as ever more star-laden (it has always been thus, but seems to have reached a point where a successful play without stars is the rarity), I worry that this same star-focus is trickling down. Certainly Off-Broadway is filled with “name” actors, so isn’t it reasonable that non-NYC companies would be desirous of the attention made possible by casting actors with the glow of fame? If Broadway maintains sales for plays by relying on stars, it’s not unreasonable for regional companies to want to compete in the same manner against the ongoing onslaught of electronic entertainment.

Again, I doubt any company is casting based solely by name, like some mercenary summer stock producer of bygone days, but one cannot help but worry about the opportunities for solid, working actors to play major leads when Diane Lane takes on Sweet Bird of Youth at The Goodman or Sam Rockwell plays Stanley Kowalski at Williamstown. Aren’t there veteran actors who deserve a shot at those roles? Yet why shouldn’t those stars, proven in other media, have the opportunity to work on stage, especially if it benefits nor-for-profit companies at the box office without compromising artistic integrity?

I’m talking out of both sides of my mouth here, and I know it. But I go back to the essence of my friend’s quandary back in 1986: what do regional theatres do when they don’t have stars? They go back to serving only their communities, which is their first and foremost priority, but they fall back off the radar of what remains of the national media that might allocate any space to stage work outside of New York. They have raised the expectations of their audiences, who love seeing famous folk in their town, on their stages, then can’t always meet them. Are theatres inadvertently contributing to a climate in which celebrity counts first and foremost? How then does the case get made for the perpetual value of the companies that either don’t – or never could – attract attention by working with big names.

Theatres play into this with their own marketing as well; it’s not solely a media issue. Even when they rigorously adhere to alphabetical company billing in programs and even ads, their graphics usually manage to feature famous faces (notably, Yale’s Streetcar does not). Though in some cases, even the billing barrier has fallen, acknowledging the foolishness in trying to pretend someone famous isn’t at the theatre, it grates a bit when regional theatres place actors “above the title” in ads or use the word “starring,” when ensemble was once the emphasis. When the season brochure comes out for the following season, or seasons, which actors seem to recur in photos, for years after their sole visit?

This past February, The New York Times placed a story about celebrity casting on its front page, as if it were something new, and ensuing reportage seemed to carry a whiff of condescension about the casting of stars in Broadway shows. Though when the Times‘ “The New Season” section came out two weeks ago, who was on the front page of it? James Bond – excuse me, Daniel Craig. Celebrity counted there as well. Because it sells.

In a week when Off-Broadway shows like The Old Friends, Mr. Burns and Fetch Clay, Make Man opened to very strong reviews, it’s worth noting that none featured big box office stars, and that as of yet, none have been announced for commercial transfers. Their quality is acknowledged, but perhaps quality alone is not enough to sustain the productions beyond their relatively small-sized venues. Time will tell. While that’s no failure, it suggests that theatre is evolving into two separate strata, unique from the commonly cited divisions of commercial/not-for-profit or Broadway/Off-Broadway/regional. Perhaps the new distinction for theatre has become “star” or “no-star.” And if that’s the case, I think it bodes ill for the health of not-for-profit companies, the vitality of audiences, and for anyone who seeks to spend their life acting, but may never get that TV show or movie that lifts them into the realm of recognition, or even higher, into fame.

Incidentally, can anyone say, quickly, who’s playing Blanche at Yale? Because, in case you forgot, the play is really about Blanche. Not the werewolf.

September 16th, 2013 § § permalink

For all the years I lived in Connecticut, I used to feel I was missing out, as I saw offers for advance screenings of films dropping into my inbox and plastered on various websites. But, alas, the screenings were focused on “major cities” and it hardly made sense for me to take a two hour drive to capitalize on an offer to see a film I could catch a few weeks later for all of $10. But now that I’m in New York, I’ve discovered that while these screenings are plenty convenient, the cost could be much greater – to the tune of $5 million for an inappropriate tweet.

For all the years I lived in Connecticut, I used to feel I was missing out, as I saw offers for advance screenings of films dropping into my inbox and plastered on various websites. But, alas, the screenings were focused on “major cities” and it hardly made sense for me to take a two hour drive to capitalize on an offer to see a film I could catch a few weeks later for all of $10. But now that I’m in New York, I’ve discovered that while these screenings are plenty convenient, the cost could be much greater – to the tune of $5 million for an inappropriate tweet.

That’s not a typo. An e-mail offer for a screening of Ron Howard’s Rush this evening, from the site previewfreemovies.com, has an extensive list of caveats about who can attend and what they’re able to say – or more accurately, everything they can’t say – if they accept such a gracious offer. I’d be out, according to their requirements, right off the bat, because they wish to prohibit anyone from the entertainment industry, market research or media from participating, since the screening is being done for market research purposes. I would say this is a pretty sloppy way to assemble a representative moviegoing sample in New York, but presumably they want “average viewers,” whoever they may be, not us media elite (what, me elite? ha!).

Now it’s worth noting that Rush screens tonight and opens Friday, so this isn’t a test screening that might result in edits and reshoots; all they can gather at this point is how the audience feels about the film. The methodology seems different than that used by Cinemascore, which one reads about, so who the results of this effort are seen by is an unanswered question. But the movie isn’t about to change in the subsequent 72 hours (now that many films debut on Thursday evenings around 9 pm).

What gets my goat about this “invitation” is the lengthy list of warnings and potential liabilities you undertake by participating. While I understand the concern about surreptitious filming (we know that bootlegs of shoddily shot screenings copntribute to movie piracy, and should be averted), the idea that a tweet or blog about a film could ruin someone’s finances is something else altogether. In this case, it’s pretty preposterous, as the film has already been screened at the Toronto Film Festival (and I’ve seen tweets about it), but this language is in place for many such advance viewing opportunities.

Frankly, I have a sneaking suspicion that if an attendee posted a few words or even a few paragraphs online that were laudatory about the film, all concerned would turn a blind eye to the praise. But if anyone of influence happened to express negative opinions, the potential for action rises. While I doubt that any company would want the negative p.r. of swooping down on some innocent Facebooker who didn’t mind the fine print, I bet they’d put the fear of god into them as an example, so they can run their marketing they way they like, with “average moviegoers” as tools to be used, rather than customers and potential supporters.

Please don’t moan to me, movie marketers, about how social media has ruined the preview process and upended your efforts; every industry has had to adjust to the revolution. But if you want to know what people think, it should be an all or nothing proposition – you get your info, but so do friends and family and followers of those you drag in with your offer of marginal value, unless you offer them something more valuable than the right to see a movie a few days early, while being subject to draconian penalties. The public shouldn’t be bought so cheaply while assuming a ridiculous risk. So I just might see Rush when it opens – and say anything I darn well please about it,wherever and whenever I want.

For the record, here’s the language that appeared in the e-mail invitation itself, verbatim:

By attending this private event you agree to all of the following:

- A Photo ID or Passport is required for admittance.

- The audience at this screening may be recorded for research purposes. By attending, you give your unqualified consent to the filmmaker and its agents and licensees to use the recording of your person and appearance and your reactions for its review in any manner in connection with the purpose of this recruited screening.

- No one over or under the above-listed age group or infants will be permitted into the theater, and if you accept this invitation, you and your guest represent that our ages are BOTH within this listed age group.

- No one involved in the entertainment advertisement, market research or media industries, or anyone who writes, blogs or otherwise reports on media in any form or forum whatsoever will be admitted.

- By accepting this invitation and attending this screening, you agree not to disclose any of the contents of the screening prior to the release of the movie to the public. If you are discovered to have written about, posted or disclosed in any manner any of the contents of the screening – including but not limited to Facebook, Twitter, blogs or any other social media outlets, we will pursue all of our legal rights and remedies against you.

- The theatre is overbooked to ensure capacity and therefore you are not guaranteed a seat by showing up at this private event.

- There is no charge to attend the screening, but as a condition to admittance, audience members are required to complete a short questionnaire following the movie.

- No audio or video recording devices will be allowed into the theater, including but not limited to camera phones and PDAs. If you attempt to use a recording device you will be removed from the theater immediately, forfeit the device and you may be subject to criminal and civil liability.

- Audience members consent to a search of all bags, jackets and pockets for cameras or other recording devices. Leave any such items at home or in your car.

- All non-camera cell phones and pagers must be off or on silent mode during the screening.

- Anyone creating a disturbance or interfering with the screening enjoyment of others in the audience will be removed from the theater.

By accepting this invitation and/or attending the screening event, you acknowledge and agree that neither you nor your guest(s) are guaranteed admission to the theater, or any specific seating if you are so admitted, and that none of you are entitled to any form of compensation if you do not get admitted into the screening or if you are offered seats that you choose to decline.

And here, also verbatim, is the language that appears in a scrolling box on the actual RSVP form. This is where it gets expensive:

CONFIDENTIALITY AND NONDISCLOSURE AGREEMENT

THIS CONFIDENTIALITY AND NONDISCLOSURE AGREEMENT (“Agreement”) is made and entered into by and between Screen Engine, LLC, a California limited liability company, dba previewfreemovies.com, (“Company”) and/or its affiliated or related companies and clients, and you, the individual confirming your attendance at this event (“Individual”). For good and adequate consideration, the receipt, adequacy and sufficiency of which are hereby acknowledged, Individual hereby agrees as follows:

Individual is or will be a guest of Company at a market research event for the purpose of viewing “works-in-progress” creative content that may be associated with movies and other media (the “Creative Content”) In the course of Individual’s viewing of the Creative Content, Individual may acquire or may be exposed to information (including, without limitation, information that is written, oral, photographed or recorded on film, tape, or otherwise), as well as any as-yet unreleased creative content. Individual agrees that he/she shall not, during the term of this Agreement, or thereafter, in perpetuity, disclose or cause to be disclosed (or confirm or deny the veracity of) to any third party or use or authorize any third party to use:

(1) Any information relating to the Creative Content, the business or interests of Company, or Company’s Affiliates, that the Company and/or its Affiliates has not revealed to the general public;

(2) Any information developed by or disclosed to Individual by Company, Company’s Affiliates, or by any third party, which is confidential to Company, its Affiliates, Clients and/or which is not known to the general public;

(3) Any information that Company, or its Affiliates instruct Individual not to disclose or confirm. The information described in (1)-(3) is hereinafter referred to collectively as the “Confidential Information”

Individual acknowledges that maintaining complete privacy and avoiding disclosure of Confidential Information are critically important to Company and its Affiliates, that Individual would not be given access to Confidential Information if Individual were not willing to agree to these terms, and protect and preserve that privacy and confidentiality, and that Individual’s full and strict compliance with this Agreement is a fundamental inducement upon which Company is specifically relying in allowing Individual to view, hear or learn of the Creative Content. Confidential Information is and shall remain the sole and exclusive property of Company and its Affiliates, and, during and after the term of this Agreement, Confidential Information, even when revealed to Individual, shall be deemed to remain at all times in the sole possession and control of Company and its Affiliates.

a.) Without limiting any other provision hereof, Individual shall not give any interviews regarding or otherwise participate by any means and in any form whatsoever, including but not limited to blogs, Twitter, Facebook, You- Tube, MySpace, or any other social networking or other websites whether now existing or hereafter created, in the disclosure of any Confidential Information or any other information relating to this Agreement, the Creative Content or the business of Company or its Affiliates. If Individual is contacted by a journalist, a representative of the media or other third party who requests that Individual disclose or confirm or deny the veracity of any of the Information covered by this Agreement, Individual shall reject said request and/or issue a “no comment”, and Individual shall immediately advise Company thereof.

b.) Company shall have the right to confiscate, (including seize and destroy the contents of) cell phones, cameras, PDAs and any and all other infringing devices, and take all necessary measures to protect its rights.

c.) Individual agrees that any breach of this Agreement will cause Company and its Affiliates and Clients incalculable damages. Such damages include all costs of any nature associated with the Creative Content, as well as the incalculable management time necessary in creating and distributing the same. Accordingly, Individual agrees that in the event of breach of this paragraph, Individual shall pay Company, upon demand, as liquidated damages, the sum of Five Million Dollar ($5,000 000.00) plus any actual out-of-pocket expense, as well as any attorney fees expended in enforcing this paragraph.

The provisions of this Agreement shall be binding upon and shall inure to the benefit of Company, its successors and assigns and to the benefit of Individual and his or her successors and assigns.

September 12th, 2013 § § permalink

Macbeth. Twelfth Night. Richard III. Romeo and Juliet. No Man’s Land. Waiting For Godot. Betrayal. The Winslow Boy.

The syllabus for a university survey course in drama? No. Instead, it’s the roster of eight of the 16 titles scheduled to open on Broadway between now and the end of 2013.

To be sure, British plays, artists and productions haven’t ever been strangers to Broadway, but this preponderance of works – featuring actors such as Jude Law, Mark Rylance, Rachel Weisz, Daniel Craig, Anne-Marie Duff, Stephen Fry, Orlando Bloom, Roger Rees, Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart – in the 40 theatres that comprise Broadway, all at the same time, is an embarrassment of riches. Add in concurrent Off-Broadway productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream with David Harewood and Kathryn Hunter (opening the new Theatre for a New Audience space in Brooklyn) and Michael Gambon and Eileen Atkins in All That Fall, and it appears that Anglophilia is running rampant in the playhouses of New York.

Much of this is coincidence, since it’s not as if producers conspire on themes. Indeed, from a marketing standpoint, it’s not necessarily even a good idea, since the theatregoers most drawn to this work may have to face some tough buying decisions unless they have unlimited resources and time. Cultural tourists won’t even be able to fit all of these terrific sounding shows in, should they fly to the city for merely a long weekend.

But whether the productions are transfers from the UK or newly minted in America, as is the case with No Man’s Land, Romeo and Juliet, and Betrayal, the British imprimatur seems as if it’s a requirement this year, even if only in part. UK director David Leveaux is staging Romeo and Juliet with a North American cast capped by Bloom. US director Julie Taymor tapped Harewood and Hunter for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, her first project since the highly-publicised and contentious Spiderman: Turn Off The Dark (a tell-all book by her collaborator Glen Berger will be released just as Midsummer performances begin). Even the US classic The Glass Menagerie is being helmed by John Doyle. Only Classic Stage Company’s Romeo and Juliet, with Elizabeth Olsen and TR Knight, is wholly comprised of American artists, though their Romeo is Japan-born.

The English theatre can certainly take pride in this abundance of talent exported to American shores, and I look forward to each and every one of these shows enthusiastically. Indeed, I’ll pass on my annual autumn trip to London since I’ll need only take the subway and not British Airways.

But it does beg the question of whether classical work can succeed on Broadway without a UK connection. Are producers giving up on our best American actors and directors taking on British and Irish pieces without at least some of that heritage in the shows’ DNA? To be sure, not-for-profit companies may lean American overall (LCT’s Macbeth is Ethan Hawke), but has public television conditioned us to desire the “genuine” article? Great American plays appear on British stages frequently, ranging from A View From The Bridge to Fences to Clybourne Park, without the perpetual need to import Americans, let alone the cream of American talent, to make them work. Yet the power of UK casting appears to be such that even multiple Macbeths are deemed economically viable, with Alan Cumming having played virtually all of the roles on Broadway only months ago and Kenneth Branagh due at the Park Avenue Armory in June 2014.

I don’t like calling attention to national divisions when it comes to art, but the fall theatre season in New York simply can’t be overlooked. Despite the luxury of all of the great theatre on tap, the timing sends the message to US actors, theatre students, critics and audiences that when it comes to staging foreign classics, the talent exchange flows more strongly from west to east than in the other direction.

But looking on the bright side, perhaps this means we’ll soon enjoy one more benefit of the English stage, and be able to buy ice cream at the interval.

September 11th, 2013 § § permalink

This afternoon on Twitter, journalists were decrying the proliferation of the word “premiere” in theatres’ marketing and press materials, especially in cases where the usage is parsing a point rather finely or declaring an outright untruth. I feel for Jason Zinoman, Johnny Oleksinski, Charles McNulty, Diep Tran, Kelly Nestruck and their peers, because at times they may have editors wanting them to take note of important distinctions, but don’t necessarily have a complete production history in order to insure accuracy. Having previously explored the obfuscations of arts communication in Decoder and Decoder II (which remain inordinately popular), it falls to me to dissect this phenomenon.

This afternoon on Twitter, journalists were decrying the proliferation of the word “premiere” in theatres’ marketing and press materials, especially in cases where the usage is parsing a point rather finely or declaring an outright untruth. I feel for Jason Zinoman, Johnny Oleksinski, Charles McNulty, Diep Tran, Kelly Nestruck and their peers, because at times they may have editors wanting them to take note of important distinctions, but don’t necessarily have a complete production history in order to insure accuracy. Having previously explored the obfuscations of arts communication in Decoder and Decoder II (which remain inordinately popular), it falls to me to dissect this phenomenon.

How has “premiere” metastasized? World premiere. U.S. premiere. East coast premiere. West Coast premiere. Professional premiere. New York premiere. Broadway premiere. Regional premiere. Area premiere. Local premiere. World premiere production. Shared premiere. Simultaneous premiere. Rolling premiere. I’m sure I’ve missed some (feel free to add them in the comments section).

So what is this all about?

It’s a sign of prestige for a theatre to debut new work, so “world” and “U.S.” premieres have the most currency. This is the sort of thing that gets major donors and philanthropic organizations interested, the sort of thing that can distinguish a company on grant applications and on brochures. You would think it’s clear cut, but you’d be wrong.

If several theatres decide to do a brand new play all in the same season, whether separately or in concert with one another, they all want to grab the “premiere” banner. After all, it hadn’t been produced when they decided to do it, they can only fit it into a certain spot, and they can’t get it exclusively, but why shouldn’t they be able to claim glory (they think). Certainly they’re to be applauded for championing the play, and reciprocal acknowledgment is worthy of note.

But still I imagine: ‘Oh, there was a festival production, or one produced under the AEA showcase code? Well surely that shouldn’t count,’ I can hear some rationalizing. ‘We’re giving it more resources and a longer run. Besides, the authors have done a lot of work on it. Let’s just ignore that production with three weeks of paid audiences and reviews. We’re doing the premiere.’

Frankly, sophisticated funders and professional journalists aren’t fooled. But there are enough press release mills masquerading as arts news websites to insure that the phrase will get out to the public. If anyone asks, torturous explanations aimed at legitimizing the claims are offered. When we get down to “coastal,” “area,” “local” and the like, it’s pretty transparent that the phrase is being shoehorned in to tag onto frayed coattails, but at least those typically have the benefit of being honest in their microcosmic specificity. That said, if multiple theatres, separately or together, champion a new play, they’re to be applauded, and reciprocal acknowledgment is worthy of note.

In the 1980s, regional theatres were being accused of “premiere-itis,” namely that every company wanted to produce a genuine world premiere so that it might share in the author’s royalties on future productions, especially if it traveled on to commercial success. Also, there was funding specifically for brand new plays that was out of reach if you did the second or third production, fueling this dynamic. Many plays were done once and never seen again because of the single-minded pursuit of the virgin work. To give credit where it’s due, that seems less prevalent, even if it has done a great deal to make the word “premiere” immediately suspect. But funders and companies have realized the futility of taking a sink or swim attitude towards new work.

To give one example about how pernicious this was, I was working at a theatre which had legitimately produced the world premiere of a new musical, and the company had been duly credited as such on a handful of subsequent productions. But when the show was selected by a New York not-for-profit company, I was solicited to permit the credit to be changed to something less definitive – and moved away from the title page as is contractually common – lest people think this was the same production and grow ‘confused’. I didn’t relent, but it’s evidence of how theatres want to create the aura of origination.

I completely understand why journalists would be frustrated by this semantic gamesmanship, because they shouldn’t have to fact check press releases, but are being forced to do so. That creates a stressful relationship with press offices, and poor perception of marketing departments, when in some cases the language has been worked out in offices wholly separate from them. Have a little sympathy, folks.

Production history of Will Power’s

Fetch Clay, Make Man

That said, at every level of an organization, truth and accuracy should be prized, not subverted. What’s happening at the contractual level insofar as sharing in revenues is concerned is completely separate than painting an accurate picture of a play’s life (the current New York Theater Workshop Playbill for Fetch Clay, Make Man provides a remarkably detailed and honest delineation of the play’s development and history, by way of example). Taking an Off-Broadway hit from 30 years ago may in fact be its “Broadway debut,” but “premiere” really doesn’t figure any longer, since there’s little that’s primal or primary about it. If you’re based in a small town with no other theatre around for miles, I suppose it’s not wrong to claim that your production of Venus In Fur is the “East Jibroo premiere,” but does anyone really care? It’s likely self-evident.

Let’s face it, any catchphrase that gets overused loses all meaning and even grows tiresome. If fetishizing “premiere” hasn’t yet jumped the shark quite yet, everyone ought to realize that there’s blood in the water.

P.S. Thank you for reading the world premiere of this post.

Thanks to Nella Vera and David Loehr for also participating in the Twitter conversation that prompted this post, which has been recapped via Storify by Jonathan Mandell, including some comments I’d not previously seen.

September 9th, 2013 § § permalink

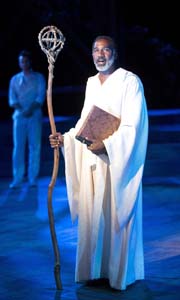

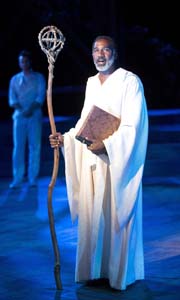

The Public Works The Tempest

Photo by Joan Marcus

There are many reasons to enthuse about The Public Theatre’s inaugural “Public Works” production of The Tempest – the conception and direction of Lear de Bessonet, the original score by Todd Almond, the perfect weather that blessed each of the three evenings it was on, the enthusiastic performances centered by the Prospero of Norm Lewis. But the greatest achievement was the participation and wrangling of some 200 non-professional performers, rallied in service of a musicalized and summarized version of Shakespeare’s play.

Billed at times as a “community Tempest,” the production utilized, according to a program insert, “106 community ensemble members, 31 gospel choir singers, 1 ASL interpreter, 24 ballet dancers, 3 taxi drivers, 12 Mexican tap dancers, 1 bubble artist (who I must have missed), 10 hip hop dancers, 5 Equity actors (though there were 6 by my count), 6 taiko drummers, 1 guest star appearance (again, I must have missed that, or simply not known the performer), and 5 brass band players.” It was an undertaking of remarkable scale that put me in mind of the deeply moving finale of the New York Philharmonic’s 80th birthday tribute to Stephen Sondheim, when the stage and aisles of Avery Fisher Hall were filled with the bodies and voices of singers uniting for “Sunday,” except that in this case, the large company was present throughout the show and the music was raucous and exuberant.

Christine Lewis & Patrick Mathieu as Alonsa & Gonzalo

Photo by Joan Marcus

The preceding litany of performers accurately suggests that this Tempest was, like Prospero’s isle, full of noises and a wide variety of styles, an at-times almost vaudeville approach to the reworked text, with a wide variety of acts sharing the same stage (I remember the Mexican tappers vividly, though I have already forgotten the pretext under which they were included). But that’s befitting a production which endeavored to engage the New York community not simply by inviting them to watch the production for free, but to participate in it as well. It was also a fitting artistic complement to The Public’s immediately preceding production at the Delacorte, a musical version of Love’s Labour’s Lost.

To be sure, this wasn’t the result of a some lunatic open call. De Bessonet and her team established relationships with specific community groups and performing ensembles and presumably they each rehearsed their segments discretely until the final days when they were assembled en masse. The program for the evening even suggests that in some cases, existing work was incorporated into The Tempest, rather than groups necessarily learning specific material. Sometimes the fragmentary nature was rather obvious (what were those cabbies doing there anyway), but at other times seamless, such as the sequence when a corps of pre-teen ballet dancers wordlessly tormented Stephano, Trinculo and Caliban.

Xavier Pacheco & Atiya Taylor as Ferdinand & Miranda

Photo by Joan Marcus

This manner of artistic engagement with the community isn’t new; the production itself was modeled on a 1915 musicalized Tempest in Harlem with a cast of 2,000. More recently, companies like Cornerstone have gone into specific communities with a handful of professionals to foster the creation of works featuring local non-professionals and there’s probably many a Music Man production which has fielded 76 trombones and more from local schools. But in Manhattan, where community based performance can be overwhelmed in the public consciousness by the sheer volume of professional arts performances, this Tempest was a reminder that a very special and joyous entertainment can emerge from the efforts of those who may not be, nor even desire to be, professional artists.

Clearly this effort was guided by expert professionals and I suspect that its budget far exceeded that of many professional productions seen in New York or around the country. Costuming alone for 200 performers takes some doing, even when many of the clothes may have been borrowed from some of the country’s top regional theatres. Just opening the Delacorte Theatre for rehearsals and performances has real cost. The level of corporate and foundation support behind this Public Works production means this isn’t likely to result in a profusion of comparable efforts.

Norm Lewis as Prospero

Photo by Joan Marcus

That said, the driving concept behind it is worthy of exploration by other groups in other cities and by other coalitions in New York as well. At a time when engagement is both a goal and a buzzword, this Tempest is a high-profile flagship that will hopefully inspire others means of mixing professionals and amateurs, that will prompt more artists to create works that encompass their community, that will even mix up audiences so that the cognoscenti sit alongside proud parents. The production once again affirmed that community theatre is not only valuable but essential, an asset to pro companies rather than a pale imitation of them.

It was also a reminder of the power of collaboration, of the intermingling of different artistic pursuits and organizations to create a blended whole. At a time when the arts are often seen as frivolous or disposable, there is enormous strength in variety and in numbers, sending a message about the essential and broad-based value of creativity and performance at every level of society and life. After all, no one arts group is a magically protected island – they are all part of a vast archipelago, threatened by rising tides that would seek to swamp them.

September 4th, 2013 § § permalink

Tommy Bazarian in “Still Life.” (Photo courtesy Yuvika Tolani).

Someone bathing on stage? Commonplace. Two people bathing together on stage? Seen it. Male and female conjoined twins spending almost the complete duration of an hour-long Bulgarian play in bathtub? For that, I needed to go to the Fringe.

Inanimate objects coming to life and talking? Oh, that’s so Toy Story. Two grapes discussing life for 80 minutes? Yup, that’s the Fringe.

I didn’t choose to see these plays. As a Connecticut native, raised on a diet of regional theatre, Broadway and the major Off-Broadway companies, I don’t usually spend a whole lot of time below Union Square. Coming out of college, my drama club friends became doctors and lawyers, so I was never compelled to see productions in fifth-floor downtown Manhattan lofts. Having only moved here a decade ago at age 40 to run the American Theatre Wing, which required me to see every show that opened on Broadway, I’m pretty mainstream by default. But for three days in August, I dove into the New York International Fringe Festival, letting an unknown person fill my days with the kind of theater I would never have selected for myself. What manner of lunatic am I? Let me explain.

As diverse as anyone manages to make their entertainment choices, they are ultimately part of a self-fulfilling plan. Whether it’s a play, a movie, a book or a TV show, our cultural choices are, for the most part, self-curated experiences that align with our existing interests. Only the truly adventurous will opt for an experience about which they know nothing or, even worse, strikes them as unappealing, especially if they have to pay for it. We don’t accidentally find ourselves at Mamma Mia! if we hate musicals, or a football game if we loathe sports.

Even though I see perhaps 125 theatre productions a year, attend about 50 movies in theaters and watch far too much television, I’m still not as omnivorous as the casual (or non-) theatergoer might perceive me to be. It may be hard to perceive limitations in the guy who enjoyed Fast and Furious 6 and is also the aesthete who reveled in the eight-hour marathon “Great Gatsby” adaptation Gatz, but I know my biases and where I prefer not to go. In the cultural arena, even if one is an avid consumer (since my teens) and a professional (since the age of 21) all at once, it’s easy to block out entire swaths of experience, pop and high culture alike. I wanted to get past that, to see if I could still expand my own repertoire.

Presenting some 185 productions in a span of a little more than two weeks, the New York Fringe, with its youthful irreverence, bare bones and anything-goes ethos, struck me as the perfect petri dish in which to conduct an experiment. Like any mad scientist, I made myself the test subject. What would be the effect of an eclectic, perhaps unpolished, theatrical barrage on the psyche of someone with such an establishment history? What would it be like to be subjected to a highly compressed theatergoing binge without any choice in what I would attend? Other than offering up 72 consecutive hours to Narratively and urging my editor (who I know only by Twitter, e-mail and a single phone conversation) to pack the schedule so long as I got time to eat, I committed to three days at the Fringe, taking in whatever I was directed to see, informed of my schedule each morning with minimal time to form advance notions. I know that my four or five shows a day for three days pales compared to die-hards who spend a week in Edinburgh taking in six or seven shows daily, but even this more measured pace struck my friends and my wife as going off the deep end. I had no idea what I’d think when I came out the other side.

And I’m off!

Day 1

My assigned agenda was waiting in my e-mail inbox when I awoke the first morning. It felt a bit like I was Jim Phelps (or Ethan Hunt, for the youngsters) on Mission: Impossible, getting my brief to topple a fictional Latin American dictatorship. Having paid no attention to literature about the Fringe in order to avoid preconceptions, I was a bit disappointed when all of the shows for the day turned out to be in theatres that I knew (although, in the case of The Players Theatre on MacDougal Street, I’d never been inside). Mild adventure at best.

My first show, about a would-be celebrity chef whose absurd concoctions had failed to catch the palate of television executives, began at two p.m. On a Wednesday. Oh, dear god: I’m a matinee lady. Here I thought I was breaking new ground and I start by making myself a cliché. But once I got over my panic, I noticed that the audience was in fact mostly younger than me – this held true at all but two shows. So even though I was a relatively senior patron, I was, comfortingly, at an experience sought out by those ostensibly hipper than myself, albeit theatre geeks like me. I kept waiting for food be thrown into the audience by the increasingly manic chef, wondering whether the front rows might at any moment be showered with diced vegetables, as if at a Gallagher gig. Alas, the premise stayed with self-flagellation for the solo show rather than audience assault.

An hour later, I’m back out into the sunshine. With more than 90 minutes to go until my next show, I check e-mails, tweet, return a couple of calls. But trying to avoid snacking and not being a coffee drinker, I simply have time to kill. My greatest concern in this first break, which is already longer than my time in the theatre so far? Would my phone battery hold out until I get home at midnight. Not unlike the experience of a long wait at an airport, I learn that finding an open power outlet at the Fringe is a beautiful thing.

Next show: a “version” of Gertrude Stein’s Four Saints In Three Acts. I’m pretty sure I saw Four Saints once. I lived in Hartford, Connecticut for a decade, where the 1934 premiere of Stein’s piece took place, and is still referenced as a cultural touchstone when the city is accused of being straight-laced. That I can’t clearly remember the production I saw in Hartford suggests this is going to be a slog.

Daniel Bellomy, Jacob Vine, Jordan Phillips, Mitch Marois,Jimmy Nicholas, Joe Ventricelli and Carter Redwood in “Gertrude Stein SAINTS!” (Photo courtesy Jordan Harrison).

Within 15 minutes of lights up, I’m grabbing for my program, because this sure isn’t anything I remember. This cast looks so young. Who on earth are they? Who put this together? After about four bios I discover a common thread: I’m watching a show featuring undergraduates from Carnegie Mellon University. And while the word’s are Gertrude’s, these kids developed the almost completely a capella score themselves, under the direction of a CMU grad student. Loath as I am to play critic (and it’s not the purpose of my Fringe binge), before it’s half over I’m ready to buy the CD (yes, yes, I know—or download it from iTunes).

Dinner. I wolf down a piece of lasagna across the street, then back into the same theatre (La Mama) for the next show, then a quick sprint across the Village for the final show of the evening. Of these, one is amateurish but well-meaning, the other cynical and tasteless. The only noteworthy moment? During one of these shows, I see the first instance (of what would eventually become four) of simulated or mimed masturbation. Yes, it will become a mini-motif over three days. I don’t realize it right away, but collectively, they add up. Does this say something about the state of our culture? Is the motif a metaphor? Is this being taught in drama schools? I shudder at the possibilities. And I won’t even go into the implications of the show in which a character rhetorically asks to be rectally assaulted with an array of increasingly uncomfortable objects.

When I get home I give my wife the briefest of recaps, as she’s already in bed and halfway to sleep. I’m feeling a bit down, wondering whether I was taking the work on its own terms, something I always advocate, or holding it to the standard of my more conventional theatergoing fare. Have my perception and taste calcified with age and experience, or did I just see a few misfires? I haven’t spent much time in 99-seat, 60-seat, 30-seat theatres. I have to make significant perceptual adjustments for the Fringe, not because I had to make allowances for their constraints, but because I haven’t fully learned to appreciate work that may be truly new, extremely youthful, and made with the barest bones.

Day 2

Time looms before me. Despite one good experience, I do not relish two more days if the ratio of “wins” to “losses” holds at the same rate. Just to add to the fun, a small medical procedure I need to have done is unexpectedly moved up from the following week to this morning. And the day’s roster requires me to consult both subway and street maps.

Confession: I’ve never been on the Lower East Side. I’ve made occasional excursions to East 4th Street (for New York Theatre Workshop and La Mama, where I’d been yesterday), to Lafayette Street (The Public) and to The Flea Theatre in TriBeCa. But in each case, I’ve taken the subway, popping up out of the ground like some cultured gopher, harvesting my treats and jumping back into the hole.

So when I emerge on Delancey Street, I am disoriented. I have to use both the map in the subway station and Google maps to determine where I am and where I’m going. I feel like a tourist. Ten years in New York, but this is terra incognita. At one point, on East Houston Street, I happen to look to my right. Huh, there’s one of those bridges to Brooklyn. I don’t even know which one. Idiot.

I’m early, of course, a congenital habit. I have close to two hours before my first show. Then inspiration hits: I’m now near all of those restaurants I read about in New York magazine (to which I’ve subscribed for decades) but never eat at. Bigger inspiration: isn’t the fabled Shopsins around here somewhere? Carefully and repeatedly consulting Yelp and Google, I find it’s inside the very building I’m in front of. After almost being thrown out by the legendary Kenny S. for having the temerity to ask if I can plug in my phone anywhere, I eat, my choice somewhat limited by my commitment to not give in to mac and cheese pancakes, which seem to be part of every third item.

I have time after lunch, so I wander the streets a bit. Here’s chi-chi WD-40, here’s Katz’s Deli, here’s Russ & Daughters. The Zagat Guide sprung to life. I briefly indulge in a fantasy of my grandparents as immigrants to the U.S., living in these tenement buildings almost a century ago, like characters in a Delmore Schwartz novel. Though I have to admit to myself that I know little of their early lives, or when they’d moved up to Connecticut. With my parents gone, I never will know. If I have heritage here, it’s lost to me.

The first show is at a basement theatre called The Celebration of Whimsy. Reinforcing the tenet embodied in the space’s name, it is also known as the C.O.W. I see a show in which two clowns, squatting in an abandoned home, are confronted by weapons-wielding home invader clowns, in a place called The Cow. This hits a particular chord of mirth for me. Is this what it was like to go to Off-Off-Broadway 50 years ago? Was it this wacky?

Another break. I quickly learn that there aren’t spots to just hang around on the Lower East Side during the day, or at least I can’t find any (I would later discover copious places in the evening, but they’re bars and I don’t drink, plus they’re exceptionally loud). Fortunately, as I trek back to East 4th Street, I pass Fringe Central. Power outlets! I tweet my delight, which results in Elena Holy, who runs the Fringe, emerging out of seeming nowhere to greet me with a hug (we first met when I interviewed her for a podcast back in 2004). Recharged electrically and emotionally, I’m off again.

The next play, about a group of aimless teens (one of whom just happens to be a Satanist) has a really terrific first act (I’m reminded of Eric Bogosian’s Suburbia), and it’s a fully shaped play, not an hour-long sketch. Unfortunately it is let down by its perfunctory second act. I recognize the playwright from her Twitter feed and her acting roles sitting in the row behind me; I have this desperate urge to chat with her about her play. But that’s presumptuous. I don’t know her, I’ve never held an artistic position in the theatre, I’m not a critic. So I remain anonymous, but make a note to see her work in the future. Boy, I wish I could talk with someone about the promise and the problems of this show. Frustrating.

The evening takes me to a venue called Teatro LATEA, housed in an enormous former public school building. I would ultimately see three out of my 13 shows here, and I’m surprised that a building with multiple theatre spaces has completely escaped my notice until now. I see a play about corporate/industrial inhumanity, followed – in the same space, an hour later –by a two-person series of blackout sketches on the theme of romance. The latter is charming, and with some polish could make for a popular entertainment with little of the bohemian aura of the Fringe about it; the former left me somewhat mystified. So day two yielded three qualified wins and only one (not such a terrible) loss. Things are looking up.

Day 3

My god, it’s beautiful out again. When I committed to this experiment, I didn’t stop for a second to think about the distances between venues, or that it might a) rain b) be above 90 degrees c) be stiflingly humid or d) all of the above. But I couldn’t ask for nicer August days in the city. I have no doubt that my attitude towards the whole experience would have been vastly different had I been sweaty or soggy or both. Maybe there is a Thespis after all.

Penko Gospodinov and Anastassia Liutova in “The Spider.” (Photo courtesy Miroslav Veselinov).

The day offers a schedule closer to what I’d originally imagined: five shows between lights up at two p.m. and the final blackout at 10:20 p.m. Today is the day I see the bathtub play and the talking grapes. It is also the day I see solo shows so dire that I am embarrassed for both the performers and the audience. One is a stand-up act that seems to have been cobbled together from a marathon of Comedy Central stand-up material, and yields almost no laughter from anyone, least of all me. Maybe I’m being punked, and this is the next Andy Kaufman? Is this a meta-commentary on stand-up comedy? I think not. The other solo pieces, not comedic, resemble nothing so much as spoofs of exercises in a consciousness-raising group from the 1970s, with a great deal of careful miming to accompany not just actions, but words and thoughts. Isn’t it enough to be told that the sun came up without having it demonstrated? If you say you’re reading, must we watch you flip pages? How much must we learn about that clichéd first trip to buy feminine hygiene products? Oy.

Together, these shows prompt me to wonder that if these made it into the Fringe, which was curated, what on earth were the rejected shows like? Am I being cruel? Perhaps, but that’s part of why I avoid being a critic. I hold very strong opinions about what I see and at this stage of my life, I probably dislike more than I like. It’s not an admirable trait. To be fair, many years ago, Ian McKellen told me that you learn more from watching bad theatre than from good theatre. I should have invited him.

Beyond the tub, the grapes and the shows I will not speak of again, the fifth piece is another promising work with a talented, if not completely in-sync cast, that starts as workplace comedy and ends as a dystopian vision from The Twilight Zone. Again, people to watch for all around in the future, especially as I’ve adjusted my internal critic to consider promising as success.

It’s a shame that I finished with one of the downer shows, as my final day doesn’t exactly send me out on a high. That said, I complete my final day with a reasonable amount of energy. I’m sufficiently stimulated by the past three days that I sleep very little that night, and awaken the next morning as if preparing to head out for day four. But in point of fact, come two p.m., when I might have been back in the theatre, I commence a multi-hour nap, and my Saturday is lost in lethargy and recuperation.

Epiphany

Did I think I would learn something new about theatre when I concocted this scheme? Perhaps. Or maybe I just wanted to set some mini-endurance goal for myself, something that would be a good story to tell friends. “Hey, remember that time I saw 13 shows in three days?” But truth be told, just as I went in blind about what I’d see, my thoughts were comparably inchoate about what I’d discover. These three days of solo theatergoing pointed out several things about myself, and about my relationship to theatre.

I had to grapple with the fact that, as the product of elite theatre, I have been molded into an elitist. In addition to the Wing, I’ve worked at, among others, Goodspeed Musicals, Manhattan Theatre Club and The O’Neill Theatre Center, all well established before I ever set foot near them. That, plus growing up in such proximity to New York, and so very close to the Yale Rep and Long Wharf Theatres, meant I was seeing very highly developed work from the start.

The construct of my Fringe experience also brought home an aspect I’ve not previously contemplated about theatergoing, namely that it is a social experience. I’ve certainly spent plenty of time in theatres (legit and movie) by myself, but it’s not my preference. However, having committed to 13 unknown shows, I couldn’t very well find one person who would want to join me, and the lack of advance schedule meant I couldn’t invite different people to different shows.

As a result, I was largely speechless for the better part of three days (uncharacteristic of me, to say the least) because I was alone and I’m not prone to striking up conversations with people in adjacent seats, or standing next to me while waiting in line. I was able to use the social media lifeline, but sparingly and only intermittently. To top it off, as someone who often attends shows late in previews or early in their runs uptown, I’m used to constantly running into people I know at the theatre; that happened at only a single show. I was among strangers virtually the whole time. My binge was a lonely adventure. That’s not in the Fringe brochure, but it was a lonely stint of my own making.

Corollary to the loneliness was the dislocation. I was a stranger in a strange land. Save for the occasional chain restaurant (one can find Subway and Baskin Robbins on the LES, though I spotted no Starbucks), every storefront was new to me, and because I hadn’t mapped out my trip, I was often at a loss regarding where to go in my limited free time. That eased by day three, as I learned that the Lower East Side isn’t some far-off kingdom; it’s merely a few blocks beyond territory that I know, a couple of stops on the F train that I’ve never taken. I will go back, on a camera safari, on a dining trip with my wife. My island has gotten a bit bigger. What the hell took me so long?

And as for letting someone else choose theatre for me? Even after seeing them, I doubt I would have made any effort to see even one of the pieces I went to, had they been described to me.

What was the scorecard? I found: one show which was an utter surprise and brought unstinting joy; a play by a very promising writer who I plan to follow; two potentially strong pieces with general appeal, but in need of greater polish; a surprisingly charming and thoughtful work about inanimate objects; a clever sketch that would have benefited from firmer direction; a funny idea that was buried inside too much exposition; a singularly unique idea that nearly wore out its welcome; a play that was well intentioned but unskilled; a puzzlement; two shows that were embarrassing for both audience and performers; and one piece that was loathsome.

But as I think about it, adding the Fringe programs to my random stacks of theatre programs that haven’t yet been sent to storage, here’s the funny thing: I wouldn’t be surprised, were I to line up any of my regular theatre-going in 13 consecutive production chunks, if I had the same range of reaction. Might the more finished work that is my usual fare yield a better ratio of hits to misses? Perhaps. But bigger theatres and bigger budgets are no guarantees of success, and I say that as someone who saw Suzanne Somers’s brief Broadway turn in The Blonde in the Thunderbird, a solo autobiography show of massive self-absorption that remains the hilarious nadir of my theatergoing life. That might have been better at the Fringe, funnily enough, perhaps performed in a bathtub. As I’ve learned, it’s all a matter of perspective.

To read this article in its originally published form, visit Narratively.

September 3rd, 2013 § § permalink

Let’s face it: railing against Broadway musicals adapted from movies is a useless exercise. As long as people keep buying tickets for them, and as long as enough of them turn out to be financial successes, they’re going to keep coming, some terrific, some blatantly and ineffectively mercenary. After all, the major Hollywood studios have now established theatrical divisions, looking to exploit their catalogues of stories and marketable titles and to them, theatrical budgets are tiny, so risk is minimal. If the pace ever slackens, I predict it’s going to be a long time coming, and likely due more to the blockbuster mentality that is overwhelming Hollywood being unable to translate to the stage. Pacific Rim, The Musical anyone?

The fact is, musicals from movies are hardly a new phenomenon. As far as I’m concerned (quoting myself from a blog post last summer), “There’s absolutely nothing wrong with musicals based on movies. When it is done with enough craft, with care and talent, no one begrudges a show its origins.”

The new Aristophanes musical!

There’s no question that lovers of musicals harbor a deep-seated desire for the wholly original musical – a story not heard or seen before, a score not lifted from some era’s Top 40 hits. There’s a particular craft at play there that hopefully won’t be lost and don’t mistake anything in this post as not desiring more of that work. But adaptation has been around for almost as long as Broadway musicals themselves; the only change is in the source. What’s puzzling is why certain sources have largely been abandoned.

Quick what was the last memorable musical you can name that was adapted from a play? And, excluding those which first became movies, what was the last solid musical based on a book? Actually, let’s drop the question of success altogether and just look at origins.