May 22nd, 2013 § § permalink

My parents were not theatergoers and my youthful memories are not filled with reveries of family trips to New York to see shows. I can remember being taken to the theatre only twice as a youth by my parents, once in 1969 in New Haven (Fiddler on the Roof, national tour) and once in about 1975 on Broadway (The Magic Show). Yet there was something embedded in my DNA which made me interested in performance; I was writing plays (almost all adaptations of existing works) in elementary school with very little frame of reference and undoubtedly even less skill.

My parents were not theatergoers and my youthful memories are not filled with reveries of family trips to New York to see shows. I can remember being taken to the theatre only twice as a youth by my parents, once in 1969 in New Haven (Fiddler on the Roof, national tour) and once in about 1975 on Broadway (The Magic Show). Yet there was something embedded in my DNA which made me interested in performance; I was writing plays (almost all adaptations of existing works) in elementary school with very little frame of reference and undoubtedly even less skill.

I longed to be an actor, and vividly remember my envy of Danny Bonaduce on The Partridge Family, thinking if he could be on TV, so could I. This was a bit odd, because I was a rather socially awkward child who didn’t mix well with most kids in my elementary years; I read constantly and had to be pushed outside into fresh air, where I invariably kept reading. Unlike many drawn to performing, music didn’t have a big role in my childhood, outside of Top 40 AM fare once I had my own little transistor radio. My parents didn’t have a record collection to speak of; I do recall my mother’s beloved two-disc set of Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, and some assorted children’s records, such as the Mary Poppins soundtrack and Danny Kaye’s Mommy, Give Me a Drink Of Water and Tubby the Tuba. Cast recordings, which loom large in the memories of theatre pros, were absent, save for Fiddler on the Roof (culturally imperative, but rarely played) and West Side Story (likewise, but we only listened to “Dear Officer Krupke”).

I longed to be an actor, and vividly remember my envy of Danny Bonaduce on The Partridge Family, thinking if he could be on TV, so could I. This was a bit odd, because I was a rather socially awkward child who didn’t mix well with most kids in my elementary years; I read constantly and had to be pushed outside into fresh air, where I invariably kept reading. Unlike many drawn to performing, music didn’t have a big role in my childhood, outside of Top 40 AM fare once I had my own little transistor radio. My parents didn’t have a record collection to speak of; I do recall my mother’s beloved two-disc set of Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, and some assorted children’s records, such as the Mary Poppins soundtrack and Danny Kaye’s Mommy, Give Me a Drink Of Water and Tubby the Tuba. Cast recordings, which loom large in the memories of theatre pros, were absent, save for Fiddler on the Roof (culturally imperative, but rarely played) and West Side Story (likewise, but we only listened to “Dear Officer Krupke”).

So I’ve often wondered how I managed to be cast in lead roles in each and every show (save one) that I auditioned for in junior high, high school, community theatre and college, and why being on stage or in speaking in front of large groups has never frightened me. I’ve come to understand that part of the appeal, and the ease, came from the stage offering the exact opposite of day to day life. On stage, I always knew what to say and when to say it, and when I did it right, I was rewarded with laughter and applause. It was a startling contrast from the uncertainty of casual interaction. Where did I learn this skill? Comedy records.

So I’ve often wondered how I managed to be cast in lead roles in each and every show (save one) that I auditioned for in junior high, high school, community theatre and college, and why being on stage or in speaking in front of large groups has never frightened me. I’ve come to understand that part of the appeal, and the ease, came from the stage offering the exact opposite of day to day life. On stage, I always knew what to say and when to say it, and when I did it right, I was rewarded with laughter and applause. It was a startling contrast from the uncertainty of casual interaction. Where did I learn this skill? Comedy records.

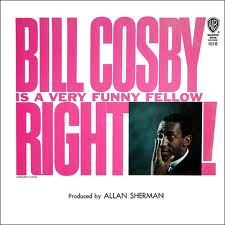

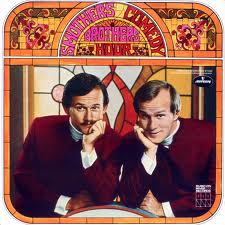

As a tween and teen in the early 70s, in the pre home video era, I was completely entranced by comedy recordings both current and from the relatively recent past. My brother and I came together primarily over our basement record player and the comedy collection scavenged from yard sales (and Monty Python on PBS). We had a bunch of the earliest Bill Cosby albums, the deeply politically incorrect Jose Jimenez In Orbit, a Smothers Brothers disc and (purchased new, smuggled in) George Carlin’s AM/FM and Class Clown. These are the ones that come to mind; there may have been more.

As a tween and teen in the early 70s, in the pre home video era, I was completely entranced by comedy recordings both current and from the relatively recent past. My brother and I came together primarily over our basement record player and the comedy collection scavenged from yard sales (and Monty Python on PBS). We had a bunch of the earliest Bill Cosby albums, the deeply politically incorrect Jose Jimenez In Orbit, a Smothers Brothers disc and (purchased new, smuggled in) George Carlin’s AM/FM and Class Clown. These are the ones that come to mind; there may have been more.

We listened to these albums over and over as if they were music, and reached the point where we knew entire routines by heart. Not just the words, but the pacing, the inflections, the comics impersonations of other characters and performers. Each routine was a song, and we would recite along with the records. We worked to perfect Carlin’s Spike Jones “hiccup” before we’d ever heard a Spike Jones record. We were mesmerized by them, long after the surprise of the jokes had faded; of course, the contraband Carlin album made us very adventuresome among our peers because of its “dirty” language (we were perhaps 12 or 13 at the time).

We listened to these albums over and over as if they were music, and reached the point where we knew entire routines by heart. Not just the words, but the pacing, the inflections, the comics impersonations of other characters and performers. Each routine was a song, and we would recite along with the records. We worked to perfect Carlin’s Spike Jones “hiccup” before we’d ever heard a Spike Jones record. We were mesmerized by them, long after the surprise of the jokes had faded; of course, the contraband Carlin album made us very adventuresome among our peers because of its “dirty” language (we were perhaps 12 or 13 at the time).

I never of thought about these records as scripts, but they were almost sacred texts to us. If we learn to perform first by imitating and later by finding our own style, then we were taking a suburban master class from performers at places like The hungry i in San Francisco before we’d ever been on an airplane and before we would have been old enough to gain admittance even had we managed the trek. The lessons ran deep: a couple of years ago, a gift set of Carlin CDs accompanied me on a road trip, and my wife was both amused and annoyed by my ability to recall every moment with precision, despite my not having heard the material in many years. Did I ever find a style of my own, moving beyond mimicry? That’s for others to say.

My actual performing years were brief, covering 1977 to 1981, 10 shows in all. I was perhaps the fussiest Oscar Madison in history, since most see me as a Felix; I probably shouted more than any one of the 12 Angry Men as Juror 3; I managed to make the characters of Will Parker and Albert Peterson the most inept dancers in their history. I suspect I was best in roles that called for comedy over movement or voice: the Woody Allen stand-in Axel Magee in Don’t Drink The Water, the meek Motel Kamzoil in Fiddler, and the dirty old man Senex in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum (my college’s newspaper noted a distinct Jewish paternalism in my performance at age 19). Whatever I had, I owed not to the performers from the Golden Age of Theatre, who I would only come to know later, but to the stand-up comedians who were the writers and performers I took close to heart – if for no other reasons than that they were repeatedly accessible on the technology that was available to me.

My actual performing years were brief, covering 1977 to 1981, 10 shows in all. I was perhaps the fussiest Oscar Madison in history, since most see me as a Felix; I probably shouted more than any one of the 12 Angry Men as Juror 3; I managed to make the characters of Will Parker and Albert Peterson the most inept dancers in their history. I suspect I was best in roles that called for comedy over movement or voice: the Woody Allen stand-in Axel Magee in Don’t Drink The Water, the meek Motel Kamzoil in Fiddler, and the dirty old man Senex in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum (my college’s newspaper noted a distinct Jewish paternalism in my performance at age 19). Whatever I had, I owed not to the performers from the Golden Age of Theatre, who I would only come to know later, but to the stand-up comedians who were the writers and performers I took close to heart – if for no other reasons than that they were repeatedly accessible on the technology that was available to me.

I do not suggest that aspiring performers should run out and start learning comedy albums by heart, though one could do worse for understanding timing and pace. Of course, now we can watch and not merely listen to comedians and work out their full routines step by step; I wonder whether the visuals would have added to our mimicry or distracted us from the deep concentration on words and delivery that took place as a ritual in our cluttered basement, our nightclub of the mind. But I am sure of one thing: there are many ways to find one’s way to the stage, and mine was through the storytelling and punchlines of some modern masters of the comedy genre.

I do not suggest that aspiring performers should run out and start learning comedy albums by heart, though one could do worse for understanding timing and pace. Of course, now we can watch and not merely listen to comedians and work out their full routines step by step; I wonder whether the visuals would have added to our mimicry or distracted us from the deep concentration on words and delivery that took place as a ritual in our cluttered basement, our nightclub of the mind. But I am sure of one thing: there are many ways to find one’s way to the stage, and mine was through the storytelling and punchlines of some modern masters of the comedy genre.

P.S. My vocal coaches were Tom Lehrer, Stan Freberg, and Allan Sherman. But that’s another story.

May 20th, 2013 § § permalink

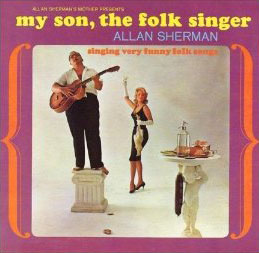

As a teen in the 1970s, I kept testing a small sociological phenomenon. When visiting a Jewish home, I would peek at the record collection of the adults in residence to see if they had the album “My Son, The Folk Singer.” If the family was Catholic or Protestant, I’d look for “The First Family” featuring Vaughn Meader. To my recollection, I never failed to find the anticipated album in the expected home, even though both records were already at least a decade old before I began my study. While this did not foretell a future career as a social anthropologist, it always gave me a little hit of satisfaction, as if I’d tumbled to some unique cultural signifier.

As a teen in the 1970s, I kept testing a small sociological phenomenon. When visiting a Jewish home, I would peek at the record collection of the adults in residence to see if they had the album “My Son, The Folk Singer.” If the family was Catholic or Protestant, I’d look for “The First Family” featuring Vaughn Meader. To my recollection, I never failed to find the anticipated album in the expected home, even though both records were already at least a decade old before I began my study. While this did not foretell a future career as a social anthropologist, it always gave me a little hit of satisfaction, as if I’d tumbled to some unique cultural signifier.

“The First Family” was a 1962 comedy album that satirized the Kennedy clan very lightly and it briefly made a star of Meader. Of course, his career as a JFK impersonator was cut short in November 1963, but for one year, his fame was such that reportedly when Lenny Bruce performed for the first time after the president’s assassination, his first words were reportedly some variant of, “Wow, Vaughn Meader’s screwed.”

“My Son, The Folk Singer” was written and performed by a previously all but unknown TV writer and producer named Allan Sherman, who was in his late 30s when the recording debuted in 1962. It was such a phenomenon that it set sales records not simply for comedy records but for the recording industry in general, and demand for Sherman’s Yiddish inflected and overwhelmingly Jewish parodies of folk and later popular songs was such that he released his first three albums (out of eight in his whole career) within a single 12-month period. For a few years he was a huge name – touring night clubs and concert venues, guest hosting for Johnny Carson, appearing in his own TV specials – but he turned out to be a fad, especially as radio formats changed, marginalizing novelty records. When he died of a heart attack in 1973 at the age of 49, his career has already been all but over for several years. I discovered Sherman at roughly the same time, unaware of his passing — I can still sing any number of his parodies at the drop of a hat.

The new biography, Overweight Sensation: The Life and Comedy of Allan Sherman by Mark Cohen (Brandeis University Press, $29.95) is a comprehensive look at the career of the man best remembered today, if at all (outside of older Jews and comedy buffs), for his tale of a summer camp sojourn gone awry, “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah.” As might be expected of a book that is part of the publishing house’s “Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life,” Sensation views Sherman through a Semitic lens, arguing for his role in popular acceptance of Jews in American culture. While Jewish comedians (and writers, performers, and so on) had flourished for decades, Cohen posits that Sherman’s success was a key crossover point that freed Jewish artists to speak openly of their race, and indeed Jewish identity was central to Sherman’s earliest work. That he was welcomed at The White House is touted as a symbol of Sherman’s cross-cultural barrier breaking, as is his popular success throughout the country.

The new biography, Overweight Sensation: The Life and Comedy of Allan Sherman by Mark Cohen (Brandeis University Press, $29.95) is a comprehensive look at the career of the man best remembered today, if at all (outside of older Jews and comedy buffs), for his tale of a summer camp sojourn gone awry, “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah.” As might be expected of a book that is part of the publishing house’s “Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life,” Sensation views Sherman through a Semitic lens, arguing for his role in popular acceptance of Jews in American culture. While Jewish comedians (and writers, performers, and so on) had flourished for decades, Cohen posits that Sherman’s success was a key crossover point that freed Jewish artists to speak openly of their race, and indeed Jewish identity was central to Sherman’s earliest work. That he was welcomed at The White House is touted as a symbol of Sherman’s cross-cultural barrier breaking, as is his popular success throughout the country.

Because of its concentration on this thesis, the book seems to give somewhat short shrift to other Jews breaking into popular consciousness and in some cases into the mainstream at about the same time; the fertile environment for recorded comedy, at its height in the early 60s, is likewise diminished. Stan Freberg (The History of The United States of America) and Tom Lehrer (“Poisoning Pigeons in the Park“) merit nary a mention (despite writing both words and music to their melodic satires before Sherman came on the scene; the latter Jewish, the former not); non-singing Jewish comics like Shelley Berman and Brooks & Reiner (The 2,000 Year Old Man) are given little attention. That’s not to say Sherman wasn’t important, but he didn’t exist in a vacuum. He burned brighter for a short time, and had a verbal dexterity admired even by Richard Rodgers, but it’s Lehrer and Freberg’s work that is often cited for its brilliance by comedians and composers a half-century later. Reiner, Brooks and Woody Allen (“The Moose“) may have started slower, but were surely more influential Jewish voices in the long run.

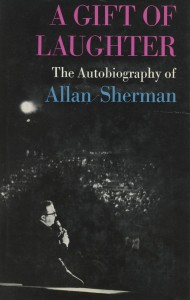

Sherman’s story plays out like the script of a thorough, culturally oriented “Behind The Music” episode, with a bit of Jewish motherdom thrown in for good measure. Cohen breaks down the comedian’s life as: he came from a terrible, broken family (such a shondeh) as a result of which he never grew up; he was a parodic genius (we’re kvelling); and already predisposed to poor health by his weight, he was done in by the trappings of success even as it left him (he’s always shicker, and cavorting with shiksas). There’s more than a hint of posthumous guilt being levied on Sherman for his various appetites (both gustatory and carnal) and shortcomings, while the enthusiasm for his culturally specific parodic work is unstinting. But the book’s research and complete lifetime overview makes it a vastly better reference document than Sherman’s autobiography, A Gift of Laughter, published in 1965 just as his career began to wane – and, according to Sensation, largely ghost-written and intermittently dishonest.

Sherman’s story plays out like the script of a thorough, culturally oriented “Behind The Music” episode, with a bit of Jewish motherdom thrown in for good measure. Cohen breaks down the comedian’s life as: he came from a terrible, broken family (such a shondeh) as a result of which he never grew up; he was a parodic genius (we’re kvelling); and already predisposed to poor health by his weight, he was done in by the trappings of success even as it left him (he’s always shicker, and cavorting with shiksas). There’s more than a hint of posthumous guilt being levied on Sherman for his various appetites (both gustatory and carnal) and shortcomings, while the enthusiasm for his culturally specific parodic work is unstinting. But the book’s research and complete lifetime overview makes it a vastly better reference document than Sherman’s autobiography, A Gift of Laughter, published in 1965 just as his career began to wane – and, according to Sensation, largely ghost-written and intermittently dishonest.

Coming from an academic press into a world that has largely forgotten him, Overweight Sensation is unlikely to spark a Sherman renaissance, but it does thoroughly memorialize the career of a man whose comedy prefigured that of other singing parodists, notably Al Yankovic, with whom he shared on obsessions with songs about food and weight (i.e. Sherman’s “Grow Mrs. Goldfarb” and “Hail To Thee, Fat Person“; Weird Al’s “Fat” and “Eat It“). It also has the bonus of an appendix featuring lyrics Sherman wrote and never released commercially; based on familiar songs, readers can easily sing them for themselves. And if he was not the sole trailblazer for Jewish life and language assimilating into mainstream culture, he certainly played a key role that is deserving of acknowledgement and remembrance, as do some of his parodies, which can still bring laughs 50 years on.

The advent of mp3s has made Sherman’s work readily accessible again after long periods out of print, and YouTube offers the opportunity to sample his oeuvre, beyond the familiarity of the hazard-filled Camp Granada. For a cursory introduction (or reminder), I recommend both the heavily Jewish inventiveness of “Sarah Jackman,” “Shake Hands With Your Uncle Max,” and “My Zelda” and the more secular jauntiness of “Eight Foot Two Solid Blue,” “You Went The Wrong Way Old King Louie,” and (with Sherman on video) “Skin” and “The Painless Dentist Song.”

P.S. No relation.

May 13th, 2013 § § permalink

Mind you, there’s only so much one can squeeze into a TV spot, but the ad I just watched managed the following in its voiceover: 1) play title; 2) key award nominations; 3) names of three lead actors; and 4) quotes from reviews. The name of the playwright, and the director, photos of the stars (not in costume), the logo for the not-for-profit theatre that produced it, and ticket ordering information appeared on screen. The piece runs only 15 seconds.

Mind you, there’s only so much one can squeeze into a TV spot, but the ad I just watched managed the following in its voiceover: 1) play title; 2) key award nominations; 3) names of three lead actors; and 4) quotes from reviews. The name of the playwright, and the director, photos of the stars (not in costume), the logo for the not-for-profit theatre that produced it, and ticket ordering information appeared on screen. The piece runs only 15 seconds.

Now this is a Broadway show and it’s Tony season, so I could simply chalk this ad up to awards fever. But it’s just another in a long line of theatre marketing tools that I see which constantly manage to skirt what strikes me as a rather important element in theatrical communication: the plot. TV time is precious, but that’s not the case in brochures, press releases and even radio spots, which are far more likely to be deployed by the majority of theatres in the country. Yet sometimes the plot is nowhere to be found.

Theatres skip over plots for one of two reasons: a) their show is a revival of a famous classic work and it’s assumed that everyone likely to be interested already knows what it’s about, or b) the theatre doesn’t actually want to say what it’s about, even if the play has never been seen before. In both cases, the decision is ill-advised.

For a classic, it may well be true that a significant portion of the likely ticket buyers already know not only the plot but the ending of Othello, A Doll’s House or Death of a Salesman. But cloaking the show solely in its author’s name and adjectives about its greatness leaves out anyone who happens to have not seen it before, and may be looking for clues as to whether it will interest them. Indeed, we forget that the great works of literature may be daunting to the uninitiated, so by bypassing even a bit of plot description, we skip the opportunity to cultivate new patrons or place the seemingly archaic work within a context that might appeal to a modern audience.

It also pays to remember that this applies to relatively recent works as well. For example, Children of a Lesser God won the 1980 Tony Award for Best Play and the lead actress in the film version won an Oscar in 1986, but how many 25 year olds know the piece? We must always be thinking of new patrons – whatever their age – not just endlessly mining the so-called “avids.”

As for avoiding the plot, the motivations can be varied. Perhaps the actual storyline could be seen as off-putting (deranged barber murders customers and his landlady bakes their remains into pies; boy blinds horses) or vague (two hobos wait endlessly for someone to show up). But skilled copy writing can put those stories into a larger and perhaps more enticing context without ever being untrue or misleading. It’s when we employ only adjectives that we’re dropping the ball; plays (and all stories) are rooted in nouns and verbs, that is to say people and action.

Even when the work in question is brand new, and there’s concern about revealing too much, it’s a mistake to say nothing; your gaggle of adjectives will less effective, since there’s no outside affirmation (as might eventually come from reviews), there’s just you trying to tell potential patrons what they’re going to think of the show if they come. (I refer you to my guides to clichéd marketing-speak and the true meanings behind it in Decoder and Decoder II.)

I’m not advocating lengthy recountings and I recognize that very often, a cursory précis of a story can be reductive; I’ve seen many authors (and artistic staffs) bridle at simplifications. But marketing and communications are not reviews or dramaturgy or literary criticism; they should be as accurate and appealing as possible, but they can’t be all-encompassing. And they must appear. The play may be the thing wherein we’ll catch the king’s conscience, but we’ve got to get him into the theatre first.

May 8th, 2013 § § permalink

I keep expecting to get jaded. Even though the actuarial tables tell me that I’m more than halfway through my life, I can still be a teenaged drama club kid, over and over again, with only the slightest provocation. Yesterday was one of those days.

I keep expecting to get jaded. Even though the actuarial tables tell me that I’m more than halfway through my life, I can still be a teenaged drama club kid, over and over again, with only the slightest provocation. Yesterday was one of those days.

Like so many in “the business,” I started out as a performer in my high school shows, both plays and musicals. But as practical considerations like finances and family, as well as negligible talent, took hold, I shifted over to administration, allowing me to be close to what I loved, but without the vagaries of an artist’s life. I have never forgotten how much I enjoyed performing, but I moderated any dreams in that regard.

When I met high school acquaintances over the years who expressed surprise that I wasn’t still on stage, I’d preempt the conversation by saying I’d be happy just to sit in a jury box on an episode of Law And Order. I was as surprised as anyone when the universe – and one very generous person on Twitter – listened, and I landed a small speaking role on Law And Order: Special Victims Unit two years ago. I still can’t believe it.

As for standing on a Broadway stage, singing? I had moderated that to a lingering desire to one day write the liner notes for a cast recording, something more within my wheelhouse. (I came very close about nine years ago, for a Tony-winning show, but it was not to be.) I am, for reasons too mundane and absurd to mention, thanked in the liner notes of the reissue of The Golden Apple, but that doesn’t count.

So when I read last week of a recording session that would include the public on a track on the cast album of the Pippin revival, my heart leapt. I filled out forms online; I placed a few calls to friends in the industry. My not-so-submerged fanboy, my long suppressed performer, went into overdrive. This was my chance to sing on a Broadway cast recording. I had to do it. It wasn’t quite being in a Broadway show, but it was the next best thing.

Mind you, I would be doing my vocalizing with some 250 strangers; I wouldn’t get my name on the recording; royalties or even payment wasn’t in the cards. Only those I told about it would even know I was there. But I would know.

Whether it was fate or phoning, I got my e-mail notice, my golden ticket, that I was “in.” Yesterday, I lined up with what turned out to be more like 500 or 600 others to play the role of “audience” on the Pippin track “No Time At All.” As we filled the auditorium at the School for Ethical Culture on New York’s Upper West Side, I took note of the surroundings, which clearly are that of a church. I considered the phrase painted above the stage/altar: “The place where people meet to seek the highest is holy ground.” I found it rather apt, in my own secular interpretation, given the degree of devotion many have to musical theatre.

I was a mix of seasoned pro and giddy youth. I said hello to some of the journalists in attendance; I greeted a Twitter pal who had gotten in by volunteering to guard one of the microphone stands near an entryway; I chatted with Kurt Deutsch, whose Ghostlight Records will be releasing the cast album; I sat with my friend Bill Rosenfield, who during his days as head of A&R for RCA/BMG was responsible for countless cast recordings (and for filling out my CD collection with those discs). At one point, Kurt’s wife joined us in the pew where I was seated, so suddenly I was singing with the tremendously talented Sherie Rene Scott, only two people separating us. The radio host, author and accomplished musical director Seth Rudetsky was seated directly in front of me; I feared he might turn at any moment and cast me out as a poseur.

But when the music team came out, I was just one voice in a big chorus, albeit one which knew the song before the first note was played. Imagine my surprise when, after being drilled on diction and rhythm, we were then taught harmony lines. I had not thought of myself as a “baritone” since high school chorus, nor had I attempted harmony in public in some 30 years. I was quickly reminded of my inability to remember anything but a melody line unless others around me are singing “my” line; scary flashbacks to my poor efforts at barbershop harmonizing ensued. Although we had been seated as we learned our parts, we were given the direction, “Let us stand,” as in worship and as in chorus rehearsals decades ago. I was surprised by the power of those three words.

But when the music team came out, I was just one voice in a big chorus, albeit one which knew the song before the first note was played. Imagine my surprise when, after being drilled on diction and rhythm, we were then taught harmony lines. I had not thought of myself as a “baritone” since high school chorus, nor had I attempted harmony in public in some 30 years. I was quickly reminded of my inability to remember anything but a melody line unless others around me are singing “my” line; scary flashbacks to my poor efforts at barbershop harmonizing ensued. Although we had been seated as we learned our parts, we were given the direction, “Let us stand,” as in worship and as in chorus rehearsals decades ago. I was surprised by the power of those three words.

Pippin’s composer/lyricist Stephen Schwartz was onstage for the session, and he was genuinely listening and tweaking what we did; Andrea Martin, although her vocal track had already been laid down in a studio, was there to egg us on. I was pleased to see them, but I know them both casually, so there wasn’t the sudden rush from being in the presence of celebrity. When Andrea first came out, she spied me and flashed a big grin and a tiny wave of recognition; I felt even more connected, more than just someone whose name got drawn along with so many others. Ah, a performer’s ego.

But the truest thrill was when every member of the assembled horde lifted their voices, including mine, in song. I had forgotten what it was like to sing in a group, in harmony, the magical mingling of one’s self with others in music, the unique vibration of the vocal cords and emotion that music can produce. Yes, a shotgun microphone was only a few feet away, but it was forgotten in the sheer happiness of being encouraged to sing full out, without embarrassment, on a tune that is undoubtedly one of the most effective and spirited earworms of the Broadway repertoire.

I’d still like to write some liner notes on day, but even if that doesn’t come to pass, I know that embedded in the Pippin cast recording is little old me, happily singing away for present and future generations of musical theatre fans. I am preposterously happy at the thought of being an indistinguishable footnote and at what is now already a memory of a magical hour.

I leave you with these random thoughts:

Thank you to every person at Pippin who made “my debut” possible.

I’ll be happy to sign your Pippin CD when it comes out (kidding, kidding).

Sing out Louise, whenever and wherever you can.

May 6th, 2013 § § permalink

Yes, I brought my camera to a Broadway show with the intention of using it. And I did.

Yes, I brought my camera to a Broadway show with the intention of using it. And I did.

Having read that the audience was invited on stage before the start of The Testament of Mary to gaze upon an assortment of props, as well as the leading lady Fiona Shaw, I brought my camera to document the event. I figured it would make for perfect art to accompany a blog post about the wisdom of a show exploiting audience curiosity in order to seed a social media marketing campaign.

Instead, I was converted.

No, not like that.

In the 36 hours since I saw the next-to-last Broadway performance, I have come to realize that the audience ambling and photobombing of Shaw was in fact an integral part of the show, and it reveals new layers to me even as I write.

Colm Toíbín’s revisionist view of the mother of Jesus, adapted by Shaw and director Deborah Warner, gave us a most ordinary Mary, who spent much of the show in a drab tunic and pants. She was remarkably modern in her speech, talked with an Irish accent, and dangled a cigarette from her lips. The set was strewn with anachronistic props: plastic chairs, a metal pail, a bird cage – a yard sale filled mostly with items from the Bethlehem Hope Depot.

Mary’s tale might be that of any Jewish mother whose son has fallen in with the wrong crowd, less disciples or worshippers than hooligans; her skepticism about her son’s miracles is hardly veiled. She spoke of the raising of Lazarus as if he had been buried alive, of the transformation of water into wine as a show-off’s trick, and wrenchingly of the crucifixion. She described those who urged her to recount her son’s life and death in specific ways, contrary to some of her own recollections; she talked about potential threats to her own safety resulting from her familial connection. She stripped bare and submerged herself completely in a pool of water for a second or two longer than might seem safe; an auto-baptism perhaps?

Mary’s tale might be that of any Jewish mother whose son has fallen in with the wrong crowd, less disciples or worshippers than hooligans; her skepticism about her son’s miracles is hardly veiled. She spoke of the raising of Lazarus as if he had been buried alive, of the transformation of water into wine as a show-off’s trick, and wrenchingly of the crucifixion. She described those who urged her to recount her son’s life and death in specific ways, contrary to some of her own recollections; she talked about potential threats to her own safety resulting from her familial connection. She stripped bare and submerged herself completely in a pool of water for a second or two longer than might seem safe; an auto-baptism perhaps?

But that’s the play. Or so we’re meant to think.

In hindsight, the play – or at least the production – began the moment Fiona Shaw took her place, Madonna-like, behind plexiglass walls, at roughly 7:40 pm before the announced 8 pm curtain. While it’s perhaps unfortunate that this device was used so soon after the Tilda Swinton-in-a-box stunt at the Museum of Modern Art, we were clearly watching a tableau vivant of the Virgin Mary as seen in countless religious icons, not an Oscar winner feigning sleep.

The moment the play proper, or perhaps I should say “the action,” began, the audience was shooed to their seats, cautioned against further photos, the glass case lifted, and Shaw quickly shed the fine vestments for the costume described earlier.

As I had stood among the crowd on stage, and it was indeed a crowd, I thought, ‘Why isn’t this better managed? Everyone is going in a different direction. People could trip, people could slip off the stage itself, they could taunt the live vulture, they could foul up the preset props.’ Even after I wormed my way up to the plexiglass and was ready to retake my seat, I couldn’t, such was the flow of people coming and going from two small stairways on a suddenly tiny stage.

I have come to realize that we were the modern day rabble, gawking at the remnants of Jesus’ death. There was no corpse, but the barbed wire we tiptoed around would later be a crown of thorns, Shaw as the Madonna was indeed a gazed-upon icon, making her transformation to flesh and blood all the more striking minutes later. We weren’t looking upon any of this with reverence, but with the avid curiosity of onlookers at a tragedy. Our actions were the curtain raiser, we were our own cast in a sequence of immersive theatre within the confines of a proscenium theatre. The vulture was gone after this prologue, since we had picked the bones of the production dry under our eager gaze; Mary was vividly alive, and therefore of no interest to a animal that feeds on carrion.

I have come to realize that we were the modern day rabble, gawking at the remnants of Jesus’ death. There was no corpse, but the barbed wire we tiptoed around would later be a crown of thorns, Shaw as the Madonna was indeed a gazed-upon icon, making her transformation to flesh and blood all the more striking minutes later. We weren’t looking upon any of this with reverence, but with the avid curiosity of onlookers at a tragedy. Our actions were the curtain raiser, we were our own cast in a sequence of immersive theatre within the confines of a proscenium theatre. The vulture was gone after this prologue, since we had picked the bones of the production dry under our eager gaze; Mary was vividly alive, and therefore of no interest to a animal that feeds on carrion.

Yes, I tweeted photos of the motionless Shaw; I imagine others did the same. I tried to get a good shot of the vulture, but it wasn’t much for posing and its black feathers in low light made it even more difficult a subject. I wasn’t about to use a flash, lest it trouble the seemingly imperturbable bird; others had no such compunction.

I have seen many coups de théâtre in my years of theatergoing, but this was the first time I had been a part of one. Even my tweeting served the piece; I was spreading the classic image of Mary to others, tipping them to the ability to photograph her themselves, in order to have their own actions questioned and subverted for the subsequent 90 minutes. As I did it, I felt there was something cheap in my actions; only in hindsight do I realize that Shaw and Warner had expertly suckered me into their game, as the modern day equivalent of a gawking bystander in ancient times.

Unfortunately, only another 1,000 people may have had the opportunity to respond to my small, complicit role as I exploited images of the show on social media, in the public relations of religious and theatrical iconography, since The Testament of Mary closed after its next performance. Perhaps it ran too short a time to become the stuff of legend, but it was, for me, a memorable experience, one martyred by what Broadway seems to demand. I hope it goes to countless better places.

all photos by Howard Sherman

May 3rd, 2013 § § permalink

Going on a theatre binge in a city other than the one in which you reside provides, inevitably, an imbalanced view of that city’s theatrical ecology. Unless you have unlimited time and an unlimited budget, you can barely scratch the surface of all that’s going on, with the possible exception of an intricately strategized Edinburgh visit in August.

For a variety of reasons, both professional and personal (plus free accommodations), I’ve taken to “helicoptering” into London a couple of times a year in an effort to see more than just the work that makes it to U.S. shores, and I’m just back from my spring visit. While it’s undoubtedly by accident, or perhaps a reflection of my own psyche, I was struck on this trip by how seven shows – only one musical; works new and revived; by British and American authors – managed to explore remarkably similar themes. My week was one that focused on looking into the past and the role that honor and integrity plays in our lives.

For a variety of reasons, both professional and personal (plus free accommodations), I’ve taken to “helicoptering” into London a couple of times a year in an effort to see more than just the work that makes it to U.S. shores, and I’m just back from my spring visit. While it’s undoubtedly by accident, or perhaps a reflection of my own psyche, I was struck on this trip by how seven shows – only one musical; works new and revived; by British and American authors – managed to explore remarkably similar themes. My week was one that focused on looking into the past and the role that honor and integrity plays in our lives.

Most obviously, Alan Bennett’s paired one-acts, Hymn and Cocktail Sticks (joined as Untold Stories in a West End transfer from The National Theatre), are autobiography with a decidedly rueful tone. In both cases, Bennett himself (embodied by Alex Jennings) recalls and interacts with his past, focusing on his relationship to music and his father in the former, and his growing intellectual disconnection from his parents in the latter. While Bennett has directly drawn on his own life in the past (he was a key character in his own The Lady In The Van years back), these short plays , written 11 years apart, show him as both reflective and perhaps regretful, a son considering his parents from a vantage point older than they were in the anecdotes on display.

The two most biographical plays (in commercial West End runs), though almost wholly fiction, were Peter Morgan’s The Audience and John Logan’s Peter And Alice. While both are rooted in historical events and real people: the former constructed from the framework of Queen Elizabeth’s weekly audience with the Prime Minister; the latter imagined from a one-time meeting of Peter Llewelyn Davis, the model for J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, and Alice Liddell Hargreaves, the template for Lewis Caroll’s Alice in Wonderland. P&A takes meta to the max, as the adult role models grapple both with the men who gave them potentially eternal life, as well as the characters that bear their name, layering the mortality of humans alongside literary perpetuity, and their memories of their younger selves. The Audience, rather than simply being a highlights reel of postwar British history, uses the weekly audiences instead to address the burden and commitment of being the queen and Logan even allows Her Majesty to interact with her younger self, long since locked away.

The two most biographical plays (in commercial West End runs), though almost wholly fiction, were Peter Morgan’s The Audience and John Logan’s Peter And Alice. While both are rooted in historical events and real people: the former constructed from the framework of Queen Elizabeth’s weekly audience with the Prime Minister; the latter imagined from a one-time meeting of Peter Llewelyn Davis, the model for J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, and Alice Liddell Hargreaves, the template for Lewis Caroll’s Alice in Wonderland. P&A takes meta to the max, as the adult role models grapple both with the men who gave them potentially eternal life, as well as the characters that bear their name, layering the mortality of humans alongside literary perpetuity, and their memories of their younger selves. The Audience, rather than simply being a highlights reel of postwar British history, uses the weekly audiences instead to address the burden and commitment of being the queen and Logan even allows Her Majesty to interact with her younger self, long since locked away.

Just as Queen Elizabeth is bound by the duty of her role, the young man who is at the center of Terence Rattigan’s classic The Winslow Boy (at The Old Vic) is potentially disgraced after an accusation of theft, breaching his family’s honor in the mind of his determined father. Though decades old (it debuted a few years before the Queen was placed in her regal straitjacket), its portrayal of a small cog being tossed aside without due process by a large and ostensibly honor-bound institution has any number of resonances in any era; the senior Winslow, hell-bent on clearing his son’s name, pronounces any number of sentiments that would be welcomed by Occupy Wall Street and veterans’ rights advocates alike. The more obviously political This House (at The National Theatre), set entirely in Britain’s Parliament between 1974 and 1979, though fascinated with the machinations of governing, also turns on tradition and honor, as the legislative body grapples with the place of long-standing practices in the face of political necessity; like The Audience, it takes its framework from history but roots itself in the humanity that manages to stay alive amid conflict that affects an entire country.

Just as Queen Elizabeth is bound by the duty of her role, the young man who is at the center of Terence Rattigan’s classic The Winslow Boy (at The Old Vic) is potentially disgraced after an accusation of theft, breaching his family’s honor in the mind of his determined father. Though decades old (it debuted a few years before the Queen was placed in her regal straitjacket), its portrayal of a small cog being tossed aside without due process by a large and ostensibly honor-bound institution has any number of resonances in any era; the senior Winslow, hell-bent on clearing his son’s name, pronounces any number of sentiments that would be welcomed by Occupy Wall Street and veterans’ rights advocates alike. The more obviously political This House (at The National Theatre), set entirely in Britain’s Parliament between 1974 and 1979, though fascinated with the machinations of governing, also turns on tradition and honor, as the legislative body grapples with the place of long-standing practices in the face of political necessity; like The Audience, it takes its framework from history but roots itself in the humanity that manages to stay alive amid conflict that affects an entire country.

Going further back into history Bruce Norris’ The Low Road (at the Royal Court) posits an amoral antihero plying his capitalist trade in colonial America. With readily apparent parallels to recent economic crises worldwide, Norris deploys as his lead character an apotheosis of financial rapaciousness, looking backwards in order to damn practices of the present day and all too recent past. In this tale, the lack of honor makes the greatest argument for it. The one musical of my visit was a revival of Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along (a West End transfer from the Menier Chocolate Factory), the backwards treading story of three friends irrevocably broken apart at the beginning of the show, only to flash ever backward to the key points of their relationship, like a film run backward as they move from missteps to success to first meetings, and as their superficial, damaged lives are restored to their youthful integrity and dreams.

Going further back into history Bruce Norris’ The Low Road (at the Royal Court) posits an amoral antihero plying his capitalist trade in colonial America. With readily apparent parallels to recent economic crises worldwide, Norris deploys as his lead character an apotheosis of financial rapaciousness, looking backwards in order to damn practices of the present day and all too recent past. In this tale, the lack of honor makes the greatest argument for it. The one musical of my visit was a revival of Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along (a West End transfer from the Menier Chocolate Factory), the backwards treading story of three friends irrevocably broken apart at the beginning of the show, only to flash ever backward to the key points of their relationship, like a film run backward as they move from missteps to success to first meetings, and as their superficial, damaged lives are restored to their youthful integrity and dreams.

So here’s the question: is London theatre consumed by these issues, or do I unwittingly choose shows which embody certain themes? Do I build my own theatrical inkblot? Honestly, I knew little of either the Bennett plays or The Low Road; I saw them because of my interest in those authors. I knew something of the premises of The Audience, This House and Peter And Alice, but no details; I was drawn by the praise of others and by the Helen Mirren and Judi Dench to two of those shows. What if I hadn’t been able to get a ticket to several of these shows? I had only purchased three before arriving in London. What if I had moved beyond the West End and the major subsidized houses into fringe venues, deciding what to see with even less foreknowledge? Perhaps I had curated my own version of PBS’s Masterpiece, cherry picking only the very best of what was on offer and leaving riskier, but perhaps even more compelling and diverse, prospects alone.

So here’s the question: is London theatre consumed by these issues, or do I unwittingly choose shows which embody certain themes? Do I build my own theatrical inkblot? Honestly, I knew little of either the Bennett plays or The Low Road; I saw them because of my interest in those authors. I knew something of the premises of The Audience, This House and Peter And Alice, but no details; I was drawn by the praise of others and by the Helen Mirren and Judi Dench to two of those shows. What if I hadn’t been able to get a ticket to several of these shows? I had only purchased three before arriving in London. What if I had moved beyond the West End and the major subsidized houses into fringe venues, deciding what to see with even less foreknowledge? Perhaps I had curated my own version of PBS’s Masterpiece, cherry picking only the very best of what was on offer and leaving riskier, but perhaps even more compelling and diverse, prospects alone.

Whatever the motivations, intentional or otherwise, I created a week that was informative and reflective, and startlingly consistent in theme even if divergent in style. And for perhaps the only time I can remember, I saw seven consecutive shows and was pleased to have seen each and every one, no mean feat for any avid theatergoer.

But I do wonder: what if I had spiced things up with Viva Forever, or tapped into Top Hat? I would have come away with a markedly different vision of the English stage and its present-day themes. Hmmmm.

My parents were not theatergoers and my youthful memories are not filled with reveries of family trips to New York to see shows. I can remember being taken to the theatre only twice as a youth by my parents, once in 1969 in New Haven (Fiddler on the Roof, national tour) and once in about 1975 on Broadway (The Magic Show). Yet there was something embedded in my DNA which made me interested in performance; I was writing plays (almost all adaptations of existing works) in elementary school with very little frame of reference and undoubtedly even less skill.

My parents were not theatergoers and my youthful memories are not filled with reveries of family trips to New York to see shows. I can remember being taken to the theatre only twice as a youth by my parents, once in 1969 in New Haven (Fiddler on the Roof, national tour) and once in about 1975 on Broadway (The Magic Show). Yet there was something embedded in my DNA which made me interested in performance; I was writing plays (almost all adaptations of existing works) in elementary school with very little frame of reference and undoubtedly even less skill. I longed to be an actor, and vividly remember my envy of Danny Bonaduce on The Partridge Family, thinking if he could be on TV, so could I. This was a bit odd, because I was a rather socially awkward child who didn’t mix well with most kids in my elementary years; I read constantly and had to be pushed outside into fresh air, where I invariably kept reading. Unlike many drawn to performing, music didn’t have a big role in my childhood, outside of Top 40 AM fare once I had my own little transistor radio. My parents didn’t have a record collection to speak of; I do recall my mother’s beloved two-disc set of Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, and some assorted children’s records, such as the Mary Poppins soundtrack and Danny Kaye’s Mommy, Give Me a Drink Of Water and Tubby the Tuba. Cast recordings, which loom large in the memories of theatre pros, were absent, save for Fiddler on the Roof (culturally imperative, but rarely played) and West Side Story (likewise, but we only listened to “Dear Officer Krupke”).

I longed to be an actor, and vividly remember my envy of Danny Bonaduce on The Partridge Family, thinking if he could be on TV, so could I. This was a bit odd, because I was a rather socially awkward child who didn’t mix well with most kids in my elementary years; I read constantly and had to be pushed outside into fresh air, where I invariably kept reading. Unlike many drawn to performing, music didn’t have a big role in my childhood, outside of Top 40 AM fare once I had my own little transistor radio. My parents didn’t have a record collection to speak of; I do recall my mother’s beloved two-disc set of Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, and some assorted children’s records, such as the Mary Poppins soundtrack and Danny Kaye’s Mommy, Give Me a Drink Of Water and Tubby the Tuba. Cast recordings, which loom large in the memories of theatre pros, were absent, save for Fiddler on the Roof (culturally imperative, but rarely played) and West Side Story (likewise, but we only listened to “Dear Officer Krupke”). So I’ve often wondered how I managed to be cast in lead roles in each and every show (save one) that I auditioned for in junior high, high school, community theatre and college, and why being on stage or in speaking in front of large groups has never frightened me. I’ve come to understand that part of the appeal, and the ease, came from the stage offering the exact opposite of day to day life. On stage, I always knew what to say and when to say it, and when I did it right, I was rewarded with laughter and applause. It was a startling contrast from the uncertainty of casual interaction. Where did I learn this skill? Comedy records.

So I’ve often wondered how I managed to be cast in lead roles in each and every show (save one) that I auditioned for in junior high, high school, community theatre and college, and why being on stage or in speaking in front of large groups has never frightened me. I’ve come to understand that part of the appeal, and the ease, came from the stage offering the exact opposite of day to day life. On stage, I always knew what to say and when to say it, and when I did it right, I was rewarded with laughter and applause. It was a startling contrast from the uncertainty of casual interaction. Where did I learn this skill? Comedy records. As a tween and teen in the early 70s, in the pre home video era, I was completely entranced by comedy recordings both current and from the relatively recent past. My brother and I came together primarily over our basement record player and the comedy collection scavenged from yard sales (and Monty Python on PBS). We had a bunch of the earliest Bill Cosby albums, the deeply politically incorrect Jose Jimenez In Orbit, a Smothers Brothers disc and (purchased new, smuggled in) George Carlin’s AM/FM and Class Clown. These are the ones that come to mind; there may have been more.

As a tween and teen in the early 70s, in the pre home video era, I was completely entranced by comedy recordings both current and from the relatively recent past. My brother and I came together primarily over our basement record player and the comedy collection scavenged from yard sales (and Monty Python on PBS). We had a bunch of the earliest Bill Cosby albums, the deeply politically incorrect Jose Jimenez In Orbit, a Smothers Brothers disc and (purchased new, smuggled in) George Carlin’s AM/FM and Class Clown. These are the ones that come to mind; there may have been more. We listened to these albums over and over as if they were music, and reached the point where we knew entire routines by heart. Not just the words, but the pacing, the inflections, the comics impersonations of other characters and performers. Each routine was a song, and we would recite along with the records. We worked to perfect Carlin’s Spike Jones “hiccup” before we’d ever heard a Spike Jones record. We were mesmerized by them, long after the surprise of the jokes had faded; of course, the contraband Carlin album made us very adventuresome among our peers because of its “dirty” language (we were perhaps 12 or 13 at the time).

We listened to these albums over and over as if they were music, and reached the point where we knew entire routines by heart. Not just the words, but the pacing, the inflections, the comics impersonations of other characters and performers. Each routine was a song, and we would recite along with the records. We worked to perfect Carlin’s Spike Jones “hiccup” before we’d ever heard a Spike Jones record. We were mesmerized by them, long after the surprise of the jokes had faded; of course, the contraband Carlin album made us very adventuresome among our peers because of its “dirty” language (we were perhaps 12 or 13 at the time). My actual performing years were brief, covering 1977 to 1981, 10 shows in all. I was perhaps the fussiest Oscar Madison in history, since most see me as a Felix; I probably shouted more than any one of the 12 Angry Men as Juror 3; I managed to make the characters of Will Parker and Albert Peterson the most inept dancers in their history. I suspect I was best in roles that called for comedy over movement or voice: the Woody Allen stand-in Axel Magee in Don’t Drink The Water, the meek Motel Kamzoil in Fiddler, and the dirty old man Senex in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum (my college’s newspaper noted a distinct Jewish paternalism in my performance at age 19). Whatever I had, I owed not to the performers from the Golden Age of Theatre, who I would only come to know later, but to the stand-up comedians who were the writers and performers I took close to heart – if for no other reasons than that they were repeatedly accessible on the technology that was available to me.

My actual performing years were brief, covering 1977 to 1981, 10 shows in all. I was perhaps the fussiest Oscar Madison in history, since most see me as a Felix; I probably shouted more than any one of the 12 Angry Men as Juror 3; I managed to make the characters of Will Parker and Albert Peterson the most inept dancers in their history. I suspect I was best in roles that called for comedy over movement or voice: the Woody Allen stand-in Axel Magee in Don’t Drink The Water, the meek Motel Kamzoil in Fiddler, and the dirty old man Senex in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum (my college’s newspaper noted a distinct Jewish paternalism in my performance at age 19). Whatever I had, I owed not to the performers from the Golden Age of Theatre, who I would only come to know later, but to the stand-up comedians who were the writers and performers I took close to heart – if for no other reasons than that they were repeatedly accessible on the technology that was available to me. I do not suggest that aspiring performers should run out and start learning comedy albums by heart, though one could do worse for understanding timing and pace. Of course, now we can watch and not merely listen to comedians and work out their full routines step by step; I wonder whether the visuals would have added to our mimicry or distracted us from the deep concentration on words and delivery that took place as a ritual in our cluttered basement, our nightclub of the mind. But I am sure of one thing: there are many ways to find one’s way to the stage, and mine was through the storytelling and punchlines of some modern masters of the comedy genre.

I do not suggest that aspiring performers should run out and start learning comedy albums by heart, though one could do worse for understanding timing and pace. Of course, now we can watch and not merely listen to comedians and work out their full routines step by step; I wonder whether the visuals would have added to our mimicry or distracted us from the deep concentration on words and delivery that took place as a ritual in our cluttered basement, our nightclub of the mind. But I am sure of one thing: there are many ways to find one’s way to the stage, and mine was through the storytelling and punchlines of some modern masters of the comedy genre.