July 10th, 2017 § § permalink

This week, Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman’s 1990 musical Assassins will have its first major New York performances since the 2004 Roundabout Theatre Company production*, in a concert version as part of City Center Encores!’s Off-Center series. Given the controversy sparked last month by The Public Theater’s Julius Caesar, in which Caesar and his wife were portrayed as analogues of Donald and Melania Trump, prompting the withdrawal of sponsors, sparking disruptions of performances and precipitating threats against the production, the theatre, the artists and the staff, it seemed an appropriate moment to speak with Weidman about how Assassins has been perceived over the past 26 years and how the newest incarnation might be received. Weidman, a former president of The Dramatists Guild, currently serves as president of the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, founded to, according to the organization’s website, “advocate, educate and provide a new resource in defense of the First Amendment.” This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This week, Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman’s 1990 musical Assassins will have its first major New York performances since the 2004 Roundabout Theatre Company production*, in a concert version as part of City Center Encores!’s Off-Center series. Given the controversy sparked last month by The Public Theater’s Julius Caesar, in which Caesar and his wife were portrayed as analogues of Donald and Melania Trump, prompting the withdrawal of sponsors, sparking disruptions of performances and precipitating threats against the production, the theatre, the artists and the staff, it seemed an appropriate moment to speak with Weidman about how Assassins has been perceived over the past 26 years and how the newest incarnation might be received. Weidman, a former president of The Dramatists Guild, currently serves as president of the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, founded to, according to the organization’s website, “advocate, educate and provide a new resource in defense of the First Amendment.” This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Howard Sherman: Given the state of discourse about public expression, given what happened with Julius Caesar in Central Park, it seems that putting up this show at this moment carries not necessarily more weight than other times, but that people may bring some other baggage to it in a different way they might have at other times. Back in 1991, it did not move to Broadway, the reason given being it wasn’t the right time, it was the first Gulf War, etc. Then there was the first planned Roundabout production, coming right after 9/11, when you and Steve and others felt it was not the right time to do the show. So is there ever a right time or ever a wrong time to do Assassins?

Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman

John Weidman: I don’t think there’s ever a wrong time to do it. I think the reception of the first production was honestly more a function of the fact that people did not know what to expect when they came into to theater. They were not prepared for the shock value of the opening number, which was a deliberate choice on our part to kind of knock the audience off balance. I think that, 25 years ago, even though there had been many adventurous musicals that had been done, some people simply assumed that the musical theater was not an appropriate place in which to tackle material that was this fundamentally serious. I think we’re well past that assumption at this point, given the kind of musicals that have been written in the last 25 years.

When the show was scheduled to be done at the Roundabout, and when we decided to delay the production after 9/11, that wasn’t a good time to do Assassins. But it wasn’t because we thought people would find the show problematic, that they would resent a show about presidential assassins in that sudden new political moment. In order to engage an audience, given the way the show’s designed and the way it’s written, it requires an audience which is, frankly, prepared to laugh in certain places, to take the humor on board. That’s part of the roller coaster ride of the show. We all felt that at that time, it was unfair to ask an audience which was grieving to come into a theater and to engage this kind of material in a way that was intermittently humorous. The show in that context simply wouldn’t work. And If it wasn’t going to work, it made sense to delay the production.

As far as now goes? When the show first opened, we had a conservative Republican in the White House, and then for eight years we had a centrist Democrat in the White House, and then for eight years we had a conservative Republican in the White House, and then we had a centrist Democrat who was black, and now we’ve got this guy. The show’s been performed continuously over the course of those 25 years in all kinds of different political and socioeconomic contexts. This is just a different one.

That said, people will obviously come into the theater from a different place, because the world outside the theater is a different place. Which will affect the way in which the members of the audience take the show on board.

But I don’t think it makes it a particularly good or bad time to do Assassins. Personally, I think it’s always a good time to do the show, because the show is meant to be provocative, and hopefully people will walk out of the theater talking about it, that it will provoke the kinds of conversations that Steve and I hoped it would provoke when we wrote it. That should happen now the way it’s happened with previous productions. They may be different conversations, but that’s what I would hope would happen.

Sherman: Have you and Steve made any changes in the show since it was last seen in New York, since the 2004 Roundabout production?

Weidman: No. The text of the show that’s going to be performed at City Center is exactly the same as the text which was performed at the Roundabout. And the text at the Roundabout was exactly the same as the text that was performed at Playwrights Horizons with the exception of “Something Just Broke,” the song which we added in London. The show’s really been what it’s been since it was first performed 25 years ago.

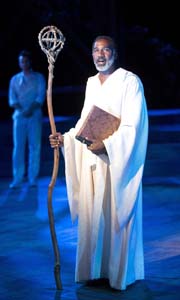

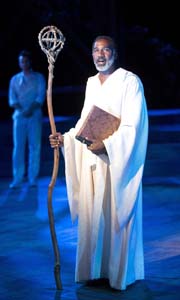

The 2017 Yale Repertory Theatre production of “Assassins” (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Sherman: Assassins was performed this spring at Yale Rep. Was there a difference in response to the show than for previous productions?

Weidman: You know, I was curious to see if there would be a difference in the way in which the show was received after the last election, and Yale was the first significant production that was available to me. I didn’t feel, sitting in the audience, as if there was any kind of shift that I was aware of in terms of the way in which the audience was connecting to the material.

Sherman: Speaking to you both as an author of the piece, and also in your role with the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, it’s fair to say that there was some very heightened conversation, and actions around the Julius Caesar, admittedly by people who didn’t see it, didn’t take the time to understand it or understand its context. In the wake of that, are you concerned at all about how, not even the audience, but how people external to the audience might choose to speak about this piece?

Weidman: The word you used was concerned. I’m not in any way worried about it. At the same time, I’m sensitive to the possibility that in this current political climate, there will be people who will react to the idea of a musical about the people who tried to attack the President, that they will react to that in a way which is similar to the way in which some people reacted to the show in 1991, when they hadn’t seen it and weren’t going to see it. They simply knew what the show was about, and they had a problem with that. That happened then and that could conceivably happen now.

I do think that we’ve had 25 years in which this show’s been performed a lot everywhere, and so people have a better idea of what the show’s ambitions are and what its intentions are. I’ve got Google alerts set on my computer to Assassins, because I’m always curious to see how the show’s being received. The reviews tend to be really good, which is always nice, but the main thing is people writing about the show all over the country, in a variety of different kinds of publications, seem to understand what Steve and I were intending. That’s really reassuring. People get the show. They can like any show, they can like it a lot or not like it a lot. But they seem to understand what we were doing, and I assume that that will be the case this time around as well.

Sherman: In reading some of the press about the prior productions and some of the commentary, one of the ways in which the show is described is that it’s about, and I’m not quoting here, I’m paraphrasing, it’s about an America that causes people who feel they have no voice to take extreme actions. As we look at politics today, there are those who say that where we are is about people who felt they were disenfranchised from the political system, and that has brought us to the real polarization that we’re at now. Might that affect people’s perceptions?

Sherman: In reading some of the press about the prior productions and some of the commentary, one of the ways in which the show is described is that it’s about, and I’m not quoting here, I’m paraphrasing, it’s about an America that causes people who feel they have no voice to take extreme actions. As we look at politics today, there are those who say that where we are is about people who felt they were disenfranchised from the political system, and that has brought us to the real polarization that we’re at now. Might that affect people’s perceptions?

Weidman: As Steve and I started to talk about this material 25 years ago, I realized at a certain point very early on that what drew me to the material was an attempt to explain something to myself which I had not understood since I was 17 years old when Kennedy was shot. The Kennedy assassination was my first real experience of loss and it was devastating to me. Two of my friends and I got together and we went down to D.C. and stood on the sidewalk as the funeral cortege went by, and all the subsequent attempts to try make sense of what happened — conspiracy theories. Was it the Cubans, was it the CIA, the FBI? It all seemed like, on some level, a waste of time to me. The fundamental question was: how could so much grief and pain be caused by one angry little man in a t-shirt with a rifle in Texas?

When Steve and I started to talk about these other personalities who had articulated a variety of wildly different motives for attacking the President, we said, ‘Well if we gather them together and look at them as a group’ – something which had not been done much, even by academics – ‘would some common grievance, some common complaint beyond what they articulated begin to emerge? And if it did, that would be a useful thing to write about.’ That is at the heart of what the piece explores. The people who, with one or two exceptions, picked up guns did tend to be, when you look at them as a group, people who were operating on the margins, the fringes of what we would consider a mainstream American experience.

In the last election, a lot of people who you and I would have identified as operating on the margins of a mainstream middle-class American experience, cast their votes in a particular way and elected a particular guy President. That does seem to suggest a different way of looking at the characters on stage in the show. I’m not quite sure what the change is. I’m not quite sure what it means in terms of how one observes their behavior and listens to what they have to say. But we are in a different political moment, and that moment will undoubtedly have an impact on how the audience responds to the piece.

I do think it will probably make for conversations on the way out of the theater which will be different from the conversations people might have had five years ago or ten years ago. I’m not sure if any of that’s clear. If it’s not, it’s because it’s something I’m still working through in my own head.

The 2004 Roundabout Theatre Company production of “Assassins” (photo by Joan Marcus)

Sherman: Given that the run is sold out, if there is conversation about why this show at this time, and if people choose to try to politicize it, is there something you would like them to know beyond the simplistic plot descriptions of a marketing brochure or a PR release about the show?

Weidman: I have always felt that that it’s essential with this show that it be allowed to speak for itself. It obviously can only speak to the audience that’s in the building, but that’s true of any theater piece. You know, somebody can describe to you what Hamlet means, but if that’s all it took to appreciate Hamlet, then you wouldn’t have to waste time listening to Shakespeare’s language for three and a half hours. I think you need to experience the piece itself, and I think that’s true of this piece. That said, Assassins is an exploration of where these vicious acts came from, in an attempt to get a better handle on how to prevent them from happening again in the future.

Sherman: Speaking to your role with the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund: is there any sense that there has been a change in people wanting to assert their own prerogative over what happens on stage? Has that changed in the past six to eight months? Does DLDF have more concerns now than in the past, or is it just consistent with the kinds of challenges that you’ve faced?

Weidman: I’m not aware of any kind of seismic shift, in terms of what people are either attempting to repress or ways in which people are self-censoring, although it would be hard to know about the second one. It may be the decisions at the high school level, it may the decisions at the amateur level, but also at the stock level, that people are making more cautious decisions in terms of what they think a school board or parent body or a subscriber base is going to be comfortable with. It’s entirely possible that they are shying away from things which they think are likely to be controversial. I would obviously hope not, because this seems to me a period when it’s important for controversial material to be produced and to become part of the national conversation.

When DLDF gave an award last year to Jeffrey Seller, and Lin-Manuel Miranda, and Thomas Kail, and the cast of Hamilton for the speech that was made from the stage when Mike Pence was in the audience, I wrote the citation and I handed the award to Jeffrey. The point I wanted to make most forcefully was that Mike Pence apparently had stood there and listened and that was fine, but the President-elect the next morning had not only castigated the cast for being rude, but he had instructed them to apologize. I said if censors tell artists what they’re not allowed to say – here we have someone going beyond that, instructing artists what they’re required to say. The latter is a genuinely frightening prospect, and I wouldn’t have thought five years ago that it was something we had to be concerned about, but I think we all feel like we’re living in a new world where anything is possible and nothing is surprising.

* There was a one-night reunion concert of the 2012 cast, held as a benefit for Roundabout.

June 12th, 2017 § § permalink

Does anyone remember last summer’s The Taming of the Shrew in Central Park? It opened with an entirely non-Shakespearean beauty pageant and talent show, led by a buffoonish figure costumed to look very much like a billionaire presidential candidate who has owned, and exploited, beauty pageants of his own. Coming in a production in which the entire cast was women, in a play that is widely considered to be misogynist in our era, it was a broad parody, a buffoonish portrayal of a political figure who had yet to consolidate his electoral power. But there was no mistaking that this was meant to be Donald J. Trump.

Now Trump is president and, by all accounts, he is once again on stage at The Public Theater’s Delacorte Theater—or rather Julius Caesar is on stage costumed to evoke the now-president, complete with a fashionable spouse who reportedly speaks in an Eastern European accent. Because Caesar is – as we all know – killed, the layering of present day politics in America over a 400-year old play (set even centuries) earlier is being said by some to have crossed a line. Lumped together with Kathy Griffin’s less classically oriented gory political theatre in which she posed with a bloody head, strongly implied to be that of the president, The Public’s Caesar quickly became a target for such media outlets as Breitbart and Fox News, even drawing a certain Donald Jr. into Twitter commentary.

“I wonder how much of this ‘art’ is funded by taxpayers?,” tweeted the presidential scion. “Serious question, when does ‘art’ become political speech & does that change things?” A Fox News tweet, headlined “NYC Play Appears to Depict Assassination of @POTUS,” was appended.

The tweet itself, for those inclined to look at such things analytically, undermined itself with its intellectual flabbiness. There is no hard line between art and politics, no absolute moment when one becomes the other. The Public Theater is hardly a stranger to melding the two, with shows ranging from Hair in the 1960s to Hamilton in 2015. It staged David Hare’s Stuff Happens and Tony Kushner’s The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide. Always socially minded, it is at least as outspoken as ever under the leadership of Oskar Eustis, the proud and vocal product of a left-wing youth. Indeed, there has been very little at The Public during Eustis’s tenure that hasn’t been easy to examine through a political prism.

Yesterday, when pressure from Breitbart, from Fox, from the Trump family, reached a point when it may have seemed to them politically, corporately, and publicly untenable from a perceptual angle to underwrite (with many others) the production, Delta Airlines disavowed The Public, pulling their support from the theatre entirely. Bank of America followed suit, but somewhat more guardedly, only pulling their support of Caesar itself. In doing so, they gave the production – for which tickets are free – vastly more attention than it had already received. Even as theatre die-hards were focused on The Tony Awards, the story of the Trump-like Caesar exploded in the media.

In statements and tweets, Delta stuck to a singular sentiment:

No matter what your political stance may be, the graphic staging of Julius Caesar at this summer’s Free Shakespeare in the Park does not reflect Delta Air Lines’ values. Their artistic and creative direction crossed the line on the standards of good taste. We have notified them of our decision to end our sponsorship as the official airline of The Public Theater effective immediately.

Bank of America stated:

Bank of America supports arts programs worldwide, including an 11-year partnership with The Public Theater and Shakespeare in the Park. The Public Theater chose to present Julius Caesar in such a way that was intended to provoke and offend. Had this intention been made known to us, we would have decided not to sponsor it. We are withdrawing our funding for this production.

In a report for Deadline, Jeremy Gerard noted that the airline’s support fell in the $100,000 to $499,000 category of sponsorship; airline arts support typically takes the form of vouchers for flights or a bank of so much value that can be used to acquire tickets, though it’s possible that there was cash involved. Certainly, that’s the likely case with Bank of America, which like many corporations has philanthropic arms, though in recent years corporate philanthropy has become inextricably linked with marketing and public relations.

Does The Public have the absolute right to stage the works it chooses and in the manner it sees fit? Yes, it certainly does. It is an independent not-for-profit organization, and what it chooses to produce, to share with audiences, is entirely the responsibility of the staff and, by extension, the board of directors. Does it have an absolute right to sponsorship or donations from any particular organizations? No. That is the result of fundraising, of a cost benefit analysis on the part of any potential sponsor or donor. If they like the work, the mission, the initiatives, of The Public – or any arts organization – individuals, government sources, foundations and corporations may choose to support it.

But there’s no mistaking the actions of Delta and Bank of America as anything but political acts as well, cloaked in the guise of corporate sensitivity. While they have not said exactly what line has been crossed by Caesar, it doesn’t seem that it’s about blood or even gore. Shakespeare is filled with violence and its results, though typically in service of a larger message. But with their decision to publicly pull funding, and even sever a long relationship in the case of Delta, these corporations are saying to those who take offense at an obviously fictional portrayal of Julius Caesar as a Trump stand-in that they don’t countenance such things, that they are shocked, shocked to find politics on stage at The Public, even a mock assassination, and don’t want to be a part of it.

As a number of sources online have noted, Delta’s outrage seems rather selective. In 2012, The Guthrie Theatre and The Acting Company staged and toured a Julius Caesar with a slim black actor being “murdered” in the Senate as Caesar, midway through the Obama presidency. Some critics remarked on the parallel to the then-president, but Delta’s sponsorship there was unruffled. Why was the death of one presidential doppelganger OK while another crossed a line? I suspect the corporate PR department of Delta is unlikely to answer that question.

By pulling their support, have Delta and Bank of America censored Caesar and The Public? Are any First Amendment rights being trampled? On an absolute level – no. Media commentary cuts both ways. The participation of a member of the governing family, however, which has blended the personal and the political in countless ways, is the kernel of official censorship. Yet the show goes on (although it ends its brief run this week) and, so far as any reports have indicated, neither company attempted to get the production altered to make it more palatable to their tastes. Indeed, it’s unclear whether either company has had any representatives see Caesar in the park, or have made their decision, cloaked behind corporate statement, based solely on the media coverage.

Will there be a backlash to the actions of these companies? Will those who support The Public and free expression in the arts now make their feelings known to these companies, and others that might jump on the bandwagon? It’s very likely. It’s also possible that those who support these decisions will affirm it as well. People will refuse to fly Delta and keep their money with Bank of America, even as others will opt in to the carrier and the financial institution. Beyond merely expressing support and dissent, the era of dueling boycotts is probably upon us. Delta and B of A may find they have become the preferred outlets for the right and even the alt-right. By making this choice in their support, and withholding of support, of the arts, they have become politically-tinged corporations, aligned with a certain point of view.

The true danger here is that supporters of the arts will begin to interrogate possible beneficiaries of their intent for each and every undertaking, keeping funds from organizations and initiatives that might be aligning themselves politically by making any comment, right or left, Republican or Democrat, liberal or conservative. After all B of A judges that the production set out to “provoke and offend.” No doubt Eustis wanted to provoke, that’s his stock in trade. But offend? That’s less clear.

Will the fear of media backlash force organizations to choose between commenting in any manner through their work on what the prevailing issues of the day may be and gaining public or private funds to do their work? Could this be the harbinger of a forced conservatism in the arts, because so many companies cannot survive without the infusion of donated funds?

It’s worth noting that the National Endowment for the Arts felt it necessary to make clear it had not supported The Public’s Julius Caesar:

The National Endowment for the Arts makes grants to nonprofit organizations for specific projects. In the past, the New York Shakespeare Festival has received project-based NEA grants to support performances of Shakespeare in the Park by the Public Theater. However, no NEA funds have been awarded to support this summer’s Shakespeare in the Park production of Julius Caesar and there are no NEA funds supporting the New York State Council on the Arts’ grant to Public Theater or its performances.

The issue evolving with Caesar in Central Park is the canary in the coal mine, and an emblem of the potentially Faustian bargain one strikes when asking for major donations. Fortunately, The Public can sustain itself even with hundreds of thousands of dollars of lost support, but they are among the largest of theatres in the country. Indeed, they may take a page from the political playbook and raise new funds off of this action against their work. But smaller companies might not be so well positioned, resulting in a flight to safer work to avoid what has just happened. Strangely enough, it is the commercial theatre, which relies solely on ticket sales for revenue, which may be in the safer position to make political statements, as was the case with the cast of Hamilton sharing thoughts with Mike Pence. Their contract is directly with the audience, and if the work finds partisans for partisan messages, then the shows will run.

Vastly more people will hear about the Trumpian Caesar than can possibly see it. They will form opinions based on media accounts, and they can and will debate whether it’s right or wrong, proper or improper, wise or foolish to stage a show in which a presidential stand-in in killed, even in the context of a classic work, taught in many high schools, where few will be surprised by the emperor’s untimely end. But the actions of Delta and B of A, especially at a time when the administration in Washington has expressed a desire to shutter both the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, risk being the first steps in a new cultural McCarthyism. That serves no one who believes in free expression, whatever they have to say, no matter how ugly or difficult what they have to express may be to hear, no matter what their politics may be. Everyone should be concerned.

UPDATE: June 12, 2017, 5:30 pm: The Public Theater released a statement this afternoon in response to the controversy surrounding Julius Caesar. It reads, in full:

We stand completely behind our production of Julius Caesar. We recognize that our interpretation of the play has provoked heated discussion; audiences, sponsors and supporters have expressed varying viewpoints and opinions. Such discussion is exactly the goal of our civically-engaged theater; this discourse is the basis of a healthy democracy. Our production of Julius Caesar in no way advocates violence towards anyone. Shakespeare’s play, and our production, make the opposite point: those who attempt to defend democracy by undemocratic means pay a terrible price and destroy the very thing they are fighting to save. For over 400 years, Shakespeare’s play has told this story and we are proud to be telling it again in Central Park.

UPDATE: June 12, 2017, 7:00 pm: The Dramatists Legal Defense Fund has issued a statement of support for The Public Theater. It reads, in part:

Good taste is a matter of opinion and an “intention to provoke” may be an integral part of a play’s mission. The works of Shakespeare are replete with representations of regicide, and potentially objectionable and graphic violence of all sorts, but Delta doesn’t appear to have had a problem with the “values” or “taste” of such depictions before. The fact is that, for hundreds of years, this particular play has been understood to be a critique of political violence, not an endorsement of it. As director Oskar Eustis explained, “Julius Caesar can be read as a warning parable to those who try to fight for democracy by undemocratic means. To fight the tyrant does not mean imitating him.” So those criticizing this production for endorsing violence against President Trump seem to be willfully misinterpreting it, for their own political ends.

UPDATE: June 13, 2017, 8 am: From Oskar Eustis’s remarks before the opening night performance of Julius Caesar on June 12:

Julius Caesar warns about what happens when you try to preserve democracy by non-democratic means and again, spoiler alert, it doesn’t end up too good. But at the same time, one of the dangers that is unleashed by that is the danger of a large crowd of people manipulated by their emotions, taken over by leaders who urge them to do things that not only are against their interest, but destroy the very institutions that are there to serve and protect them. This warning is a warning that is in this show and we’re really happy to be playing that story for you tonight.

What I also want to say, and in this I speak, I am proud to say for The Public Theater past, present and I hope future, for the staff of The Public Theater, for the crews at The Public Theater, for the board of directors of the Public Theater, for Patrick Willingham and myself, when I say that we are here to uphold the Public’s mission, and The Public’s mission is to say that the culture belongs to everybody, needs to belong to everybody, to say that art has something to say about the great civic issues of our time and to say that like drama, democracy depends on the conflict of different points of view. Nobody owns the truth. We all own the culture.

May 19th, 2015 § § permalink

The story practically writes itself: fundraiser for anti-censorship group gets censored. Ironic headline, attention-grabbing tweet, you name it. That’s exactly what appears to have happened in the past few days as the Sheen Center for Thought and Culture’s decision to cancel a rental contract with the theatre group Planet Connections Theatre Festivity has been made public. Planet Connections was producing a one-night event, “Playwrights for a Cause,” on the subject of censorship, which would in part benefit the National Coalition Against Censorship.

The story practically writes itself: fundraiser for anti-censorship group gets censored. Ironic headline, attention-grabbing tweet, you name it. That’s exactly what appears to have happened in the past few days as the Sheen Center for Thought and Culture’s decision to cancel a rental contract with the theatre group Planet Connections Theatre Festivity has been made public. Planet Connections was producing a one-night event, “Playwrights for a Cause,” on the subject of censorship, which would in part benefit the National Coalition Against Censorship.

“Neil LaBute’s Anti-Censorship Play Is Censored, With Chilling ‘Charlie Hebdo’ Echoes,” was the headline of an article by Jeremy Gerard for Deadline. “Neil LaBute NYC Anti-Censorship Theater Event ‘Censored’ to Prevent Muslim Outrage,” topped a piece by Kipp Jones for Breitbart News. “Sheen Center Cancels Event Featuring Neil LaBute Play About ‘Mohammed’” was the title for Jennifer Scheussler’s story in The New York Times.

In the wake of the cancelation, the situation was described in a press release:

“Playwrights For A Cause,” an evening of plays by award-winning playwrights Erik Ehn, Halley Feiffer, Israel Horovitz and Neil LaBute, and a panel discussion concerning censorship in climate science and more inclusion of LGBT, women, and minorities in the arts, originally scheduled for June 14, 2015 at The Sheen Center at 18 Bleecker Street, has been canceled by the management of The Sheen Center.

Although their management originally approved the event and accepted full payment for the venue, a recent change in management resulted in the Center’s decision that some of the speeches the panel speakers were going to make, along with Neil LaBute’s play Mohammed Gets A Boner, are not acceptable or compatible with their mission statement. The diverse panel of speakers included Cecilia Copeland, speaking on the censorship of women in the arts; Kaela Mei-Shing Garvin, speaking on the censorship of environmentalists and climate scientists; Michael Hagins, speaking on the censorship & underrepresentation of minorities in the arts; and Mark Jason Williams, speaking on the censorship of LGBT artists.

On Tuesday, May 12, The Sheen Center canceled the entire event, including the Planet Connections opening night party which – ironically – was benefitting the National Coalition Against Censorship.

Upon my inquiry as to the cause of the cancelation, William Spencer Reilly, executive director of the Sheen Center, responded:

At the Sheen Center we are 100% for the right to free speech for every American, and always will be. However, when an artistic project maligns any faith group, that project clearly falls outside of our mission to highlight the good, the true, and the beautiful as they have been expressed throughout the ages.

We were disappointed to learn only a few days ago that one of the plays commissioned by Planet Connections Theater Festivity for the Playwrights For a Cause benefit event was called “Mohommad Gets a Boner” [sic]. We were totally unaware of this, and their Producing Artistic Director was fully cognizant that plays of this nature were unacceptable vis a vis our contract. (That contract, FYI, was with Planet Connections Theater Festivity, not with National Coalition Against Censorship.)

In light of this clear offense to Muslims, I decided to cancel the contract. Just as newspapers the world over have chosen not to publish cartoons offensive to Islam, I chose not to provide a forum for what could be incendiary material. At the Sheen Center, we cannot and will not be a forum that mocks or satirizes another faith group.

I am confident that the programming at the Sheen Center will continue to demonstrate our commitment to meaningful conversation about important issues, and will do so in a respectful manner — to people of all faiths, or of no particular faith.

Reilly wrote, in a separate e-mail, that he learned of the content of “Playwrights for a Cause” from a staff member on May 11, saying that his staff knew of three of the plays prior to his start as executive director in late January, that he signed the contract on February 10, and that his staff only learned of the La Bute play on May 8, when they “discovered” it on the Planet Connections website.

* * *

Before continuing, I should note my pre-existing relationship with NCAC. I have worked collaboratively with them on several instances of school theatre censorship, most notably on the cancelation of a production of Almost, Maine in Maiden NC and most recently on a threat to student written plays in Aurora, CO. Last year, they named me as one of their “Top 40 Free Speech Defenders.” They first informed me of the cancelation of “Playwrights for a Cause” because they were seeking suggestions of where they might relocate the event, and they did not solicit me at any time to write about the situation.

* * *

In the wake of the cancelation, the NCAC indicated to me that the contract for the event, signed by Planet Connections, provided for cancelations pertaining to content concerns. The statement from the Sheen Center (“unacceptable vis a vis our contract”) seemed to confirm that proviso. However, when I asked Glory Kadigan, producing artistic curator of Planet Connections about provisions for cancelation in the contract, she responded,

It does say no abortions on the premises. And it does say it can’t be pornographic. However the Sheen did not cite pornography as the reason they were breaking contract. They cited religion. I do not see anything in the contract that states ‘religious differences’ as a reason they are allowed to break contract. I also can’t find a clause that states that ‘not upholding their mission’ is a reason they can break contract.

Kadigan reaffirmed this in a subsequent e-mail:

When breaking contract with us – [a Sheen staffer] stated in an email that they had a right to break contract for “religious differences/being offensive to a religion” and not upholding their mission statement. The contract does not state this anywhere that we can find. This was just something she said in an email when breaking contract but it is not actually in the contract.”

Kadigan also said there was no provision in the contract for review or approval of content. In a follow-up e-mail, after two prior exchanges, I asked Reilly if he could share the specific contract language that provided for cancelation due to material that might prove offensive to any religious group. I received no response. He also did not respond to my inquiry asking if the decision to cancel the contract based solely on the La Bute play or if the content by the featured speakers part of the decision.

* * *

The website of the Sheen Center for Thought and Culture doesn’t make explicit that it’s a project of New York’s Catholic Archdiocese, although it does so in a current job listing for a managing director position on the New York Foundation for the Arts website. However, there are clear public indications that the new arts center has a Catholic underpinning, via its mission statement:

The website of the Sheen Center for Thought and Culture doesn’t make explicit that it’s a project of New York’s Catholic Archdiocese, although it does so in a current job listing for a managing director position on the New York Foundation for the Arts website. However, there are clear public indications that the new arts center has a Catholic underpinning, via its mission statement:

The Sheen Center is a forum to highlight the true, the good, and the beautiful as they have been expressed throughout the ages. Cognizant of our creation in the image and likeness of God, the Sheen Center aspires to present the heights and depths of human expression in thought and culture, featuring humankind as fully alive. At the Sheen Center, we proclaim that life is worth living, especially when we seek to deepen, explore, challenge, and stimulate ourselves, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, intellectually, artistically, and spiritually.

“Sheen Center for Thought and Culture” is also not the complete name of the venue, since its letterhead notes that it is in fact “The Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen Center for Thought and Culture.” I wouldn’t begin to suggest that the Center is hiding its affiliation with the church, but it is inconsistent in making the relationship clear.

I think it would benefit the Sheen Center enormously to clarify this, because a religious organization certainly has the right to determine what activities are appropriate in its own facilities. In making its facility available to outside groups for rent, rather than relying solely on its own productions, it behooves the Center to make clear how they might choose to assert their prerogative.

In an article last year in the Wall Street Journal, Elena K. Holy, who runs the New York International Fringe Festival, an early tenant of the Center, discussed her conversations with the Center’s leadership about content, prior to Reilly’s tenure:

The new spaces appealed to Ms. Holy, whose festival typically includes shows that would raise the eyebrows of conservative churchgoers. “We’ve had conversations about it,” said Ms. Holy. “They approached us. And my initial response was ‘Are you sure?'”

Ms. Holy said she was given no restriction on style or content, with one caveat: “They wanted to avoid anything that is hateful about a one group of people. And that probably wouldn’t be accepted to Fringe NYC anyway.”

Of course, the Fringe has the benefit of playing in more than a dozen venues, so presumably it can program its work at the Center accordingly, to avoid running afoul of its content restrictions. From this year’s crop of upcoming productions at the Fringe, I would say we’re unlikely to see Van Gogh Fuck Yourself, Virgin Sacrifice, The God Gaffe, or Popesical at the Sheen Center. I have no idea what they would make of An Inconvenient Poop or I Want To Kill Lena Dunham.

I do find myself wondering about another booking at The Sheen Center, specifically The Public Theater’s Emerging Writers Group Spotlight series. Since the beginning of April, and concluding next week, The Public has presented two free readings of each of ten new plays. While the titles don’t indicate any potential controversy as La Bute’s did – they include Optimism, The Black Friend, The Good Ones and Pretty Hunger – it’s hard not to wonder whether ten new plays by young writers by sheer coincidence manage to not make any statements that could be perceived as contrary or insulting to any faith. Since it doesn’t appear that the Sheen Center requires script material to be submitted in advance, is it possible that if a Sheen staff member attended a 3 pm reading in The Public’s series and heard statements they deemed to be contrary to the center’s mission, the 7 pm reading of the same script might be prevented from going on?

* * *

Reilly stated that the Center is “100% for the right to free speech for every American.” However, truly free speech means that we have to allow for both words and ideas that may not be acceptable to everyone. As a project of the Catholic Church, the Sheen Center certainly has the absolute right, as do all religious institutions in the US, to assert its prerogative over what is said and performed on its premises – but that is not 100% free speech for their tenants during their stay, even if the goal of restrictions is to foster, in Reilly’s words, “meaningful conversation that reaches for understanding and not polarization.”

While Reilly’s comments were not shared with her, Kadigan, in her final e-mail to me, seemed to directly confront the idea that the event was meant to polarize. She wrote:

‘Playwrights For A Cause’ is a great event in which we are building bridges. We had two Muslim actors performing that evening who were going to be on our panel. We also have African American artists performing and Asian American writers speaking. Women playwrights and LGBT playwrights were also going to be on the panel. Erik Ehn (one of the other presenting writers) is a devout Catholic. Israel Horovitz is Jewish. All of these people would be on the panel so we had a lot of different opinions/voices.

The events of the past week make it abundantly clear why the Sheen Center needs to be more transparent in its affiliation and restrictions. It should not enter into rental contracts which may be canceled for content concerns unless it makes explicitly clear what lines cannot be crossed in its facility – allowing arts organizations seeking to use the facility to consider whether they want their work subject to such scrutiny, or to work in a facility that imposes such content limitations on others. That way, all parties can be fully informed in their dealings at the very start, understanding that the Sheen Center, in the words of New York Times reporter David Gonzalez, “was envisioned as a vehicle for the church to evangelize through culture and art.”

As for “Playwrights for a Cause”? I’m told by the National Coalition Against Censorship that they and Planet Connections may have a line on a new venue. I hope they do (maybe even one I suggested), and that the result of this conflict will be to fill whatever theatre they end up performing in. After all, one of the results of silencing speech, even in those rare cases where the right exists to do so, usually has the effect of spreading the original message even further.

Update May 19, 2:45 pm: Planet Connections has announced that “Playwrights for a Cause” will take place as scheduled on June 14 at New York Theatre Workshop. However, the program will no longer include Neil LaBute’s piece. The playwright released a statement regarding his decision to withdraw the piece:

Unfortunately the event was starting to become all about my play and its title and not about the fine work that Erik Ehn, Halley Feiffer and Israel Horovitz were also presenting that evening, along with the accompanying speeches and the cause of the evening itself. “I had hoped my work would be viewed on its own merits rather than overshadow our message or become a beacon of controversy. I am honestly not interested in stirring hatred or merely being offensive; I wanted my play to provoke real thought and debate and I now feel like that opportunity has been lost and, therefore, it is best that I withdraw the play from “Playwrights For A Cause.”

Howard Sherman is the director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama.

September 9th, 2013 § § permalink

The Public Works The Tempest

Photo by Joan Marcus

There are many reasons to enthuse about The Public Theatre’s inaugural “Public Works” production of The Tempest – the conception and direction of Lear de Bessonet, the original score by Todd Almond, the perfect weather that blessed each of the three evenings it was on, the enthusiastic performances centered by the Prospero of Norm Lewis. But the greatest achievement was the participation and wrangling of some 200 non-professional performers, rallied in service of a musicalized and summarized version of Shakespeare’s play.

Billed at times as a “community Tempest,” the production utilized, according to a program insert, “106 community ensemble members, 31 gospel choir singers, 1 ASL interpreter, 24 ballet dancers, 3 taxi drivers, 12 Mexican tap dancers, 1 bubble artist (who I must have missed), 10 hip hop dancers, 5 Equity actors (though there were 6 by my count), 6 taiko drummers, 1 guest star appearance (again, I must have missed that, or simply not known the performer), and 5 brass band players.” It was an undertaking of remarkable scale that put me in mind of the deeply moving finale of the New York Philharmonic’s 80th birthday tribute to Stephen Sondheim, when the stage and aisles of Avery Fisher Hall were filled with the bodies and voices of singers uniting for “Sunday,” except that in this case, the large company was present throughout the show and the music was raucous and exuberant.

Christine Lewis & Patrick Mathieu as Alonsa & Gonzalo

Photo by Joan Marcus

The preceding litany of performers accurately suggests that this Tempest was, like Prospero’s isle, full of noises and a wide variety of styles, an at-times almost vaudeville approach to the reworked text, with a wide variety of acts sharing the same stage (I remember the Mexican tappers vividly, though I have already forgotten the pretext under which they were included). But that’s befitting a production which endeavored to engage the New York community not simply by inviting them to watch the production for free, but to participate in it as well. It was also a fitting artistic complement to The Public’s immediately preceding production at the Delacorte, a musical version of Love’s Labour’s Lost.

To be sure, this wasn’t the result of a some lunatic open call. De Bessonet and her team established relationships with specific community groups and performing ensembles and presumably they each rehearsed their segments discretely until the final days when they were assembled en masse. The program for the evening even suggests that in some cases, existing work was incorporated into The Tempest, rather than groups necessarily learning specific material. Sometimes the fragmentary nature was rather obvious (what were those cabbies doing there anyway), but at other times seamless, such as the sequence when a corps of pre-teen ballet dancers wordlessly tormented Stephano, Trinculo and Caliban.

Xavier Pacheco & Atiya Taylor as Ferdinand & Miranda

Photo by Joan Marcus

This manner of artistic engagement with the community isn’t new; the production itself was modeled on a 1915 musicalized Tempest in Harlem with a cast of 2,000. More recently, companies like Cornerstone have gone into specific communities with a handful of professionals to foster the creation of works featuring local non-professionals and there’s probably many a Music Man production which has fielded 76 trombones and more from local schools. But in Manhattan, where community based performance can be overwhelmed in the public consciousness by the sheer volume of professional arts performances, this Tempest was a reminder that a very special and joyous entertainment can emerge from the efforts of those who may not be, nor even desire to be, professional artists.

Clearly this effort was guided by expert professionals and I suspect that its budget far exceeded that of many professional productions seen in New York or around the country. Costuming alone for 200 performers takes some doing, even when many of the clothes may have been borrowed from some of the country’s top regional theatres. Just opening the Delacorte Theatre for rehearsals and performances has real cost. The level of corporate and foundation support behind this Public Works production means this isn’t likely to result in a profusion of comparable efforts.

Norm Lewis as Prospero

Photo by Joan Marcus

That said, the driving concept behind it is worthy of exploration by other groups in other cities and by other coalitions in New York as well. At a time when engagement is both a goal and a buzzword, this Tempest is a high-profile flagship that will hopefully inspire others means of mixing professionals and amateurs, that will prompt more artists to create works that encompass their community, that will even mix up audiences so that the cognoscenti sit alongside proud parents. The production once again affirmed that community theatre is not only valuable but essential, an asset to pro companies rather than a pale imitation of them.

It was also a reminder of the power of collaboration, of the intermingling of different artistic pursuits and organizations to create a blended whole. At a time when the arts are often seen as frivolous or disposable, there is enormous strength in variety and in numbers, sending a message about the essential and broad-based value of creativity and performance at every level of society and life. After all, no one arts group is a magically protected island – they are all part of a vast archipelago, threatened by rising tides that would seek to swamp them.

January 31st, 2013 § § permalink

If supply and demand is a fundamental tenet of economics, then the tweet offer last summer from New York’s Soho Rep, during its sold-out run of Uncle Vanya, made no sense – “99¢ Sunday performance tonight at 7.30pm”. Why would it undermine something so desired as a seat to this show? Why wasn’t the price for this heretofore unavailable cache of seats $299.99?

As explained on its website: “Soho Rep is thrilled to offer 99¢ Sundays on selected Sunday performances to make our shows accessible to the widest audiences possible.”

The catch was that one could only buy the tickets, in person, an hour before the show. While admiring the gesture, I had visions of hundreds of people showing up and most being disappointed, because Soho Rep seats only 75.

Certainly one could look at this offer and think it is great value. That is true for those who were able to buy a seat. For those who were turned away, it was a disappointment and loss of time. And time, to use another basic economic tenet, is money. These days, however, the cost-value equation in theatre is vastly more complicated than ever before. As price has become fluid, it is hard to determine where true value lies.

When people wait in line, sometimes overnight, for the Public Theater’s free Shakespeare in Central Park, the ticket they get is indeed gratis. But if seven or eight hours sleeping among strangers outdoors results in attendance at a disappointing show, which can happen, then there was a high cost for little value (or, with a great show, a cashless bargain), calculable only by a subjective assessment of the worth of each individual’s time (although the overnight experience is its own type of participatory theatre).

While the time commitment necessary for acquiring tickets for Shakespeare in the Park is likely much greater than that required for 99¢ Sunday at Soho Rep (unless one is lucky enough to secure a ticket through the ‘virtual line’ online), the odds are also more favourable, since the open-air Delacorte seats some 2,000 per performance and every single performance is free, although the commitment to acquire a ticket carries risk through the final curtain – should it begin to rain ten minutes into the performance, the show may have to stop and all value is lost.

To go to the opposite end of the spectrum, take Book of Mormon, arguably the hottest ticket on Broadway. The least expensive ticket is priced at $69, but if you can secure one, it may well be for a performance months away. If you do not want to wait so long, you can, if you can afford it, buy a VIP seat for up to $500. This is a pure case of supply and demand, but it is not new. Eleven years ago, The Producers began offering premium seating at $488 per ticket. There were, then as now, various expressions of dismay, but desire trumps thrift.

Some might argue that the scarcity and cost of Mormon serves to make the experience even more valuable, as price can be an expression of worth. Having seen the show becomes a status symbol. In a unique move, perhaps an effort to diffuse frustration on the part of thwarted or economically constrained would-be ticket buyers, Mormon periodically holds ‘fan appreciation day’ performances, distributing tickets for free, akin to the Shakespeare in the Park model.

What falls between these scenarios? Rush tickets, sold on the day of the show or shortly before curtain, have been common in regional theatre fordecades. Somewhat newer ‘pay what you can’ performances are offered by some companies at early previews. Broadway shows have adopted the ‘ticket lottery’ model, holding back front-row seats at young-skewing shows such as Wicked or American Idiot, available at low price through a raffle two hours prior to curtain. In most of these cases, access to the theatre itself is essential. Every instance carries risk (will you get a ticket?), personal cost (time and effort) and value (cheap tickets).

In the UK, the Barclays Front Row scheme at the Donmar Warehouse is a lottery-rush hybrid, guaranteeing 42 low-priced seats at each performance, sold Monday mornings for the coming week (with a website clock counting down to the moment of release).

Discounting is rife on Broadway. All but the biggest hits usually have discount offers, sometimes as much as 40% off the declared value, that can be uncovered with an internet search, or in your mailbox if you are a regular theatregoer. Discounts not only allow, but also encourage, advance sales, with no great time investment. Producers trade savings for guaranteed money in the till.

The TKTS booth in Times Square may yield a 50% off price, only day-ofshow and it requires your time and presence, as lines can be long and subject buyers to the vagaries of weather (in contrast to the Leicester Square booth in London, where I have never waited more than five minutes). Both the UK and US TKTS booths have partially reduced potential disappointment by listing available shows online or by mobile app. The actual discount can be variable.

In another iteration of price/value matrix for theatre tickets, dynamic pricing seems the most clear-cut exemplar of supply and demand. I say ‘seems’ because those who employ such systems, in which prices shift according to popularity, tend only to shift prices upward opportunistically, such as increases during holiday weeks, or as a limited run approaches capacity. Price reductions are not usually found at the box office. Price charts in Broadway theatres are now all displayed on video monitors, the easier to alter as needed. Dynamic pricing is not employed only by commercial productions – subsidized theatres use it as well, raising for some the question of whether not-for-profit theatres are now pursuing profits, or simply maximising their income to support ongoing artistic and community efforts.

There is one more model of the theatrical price-value challenge, seen in the £12 Travelex season at the National Theatre in London and the $25 price for all seats, thanks to Time Warner, at New York’s Signature Theatre. These both offer great value at a most reasonable cost, as both are exceptional companies. The sponsors that make such programmes possible, as well as the theatre staff who secure the funds, are to be applauded. But with the stated goal of making theatre accessible to everyone, it is interesting to consider what both the short-term and long-term implications will be. When top-notch theatre is offered at an artificially low price, does it make the challenge of selling tickets for every competing organization that much more difficult? Could these prices simply be providing those who can afford market price a discount they never sought? Will patrons forgo comparable theatre devoid of subsidy?

In the jungle of discounts and rising costs, we have to look at the National, Donmar and Signature efforts, and others like them, as the start of admirable and essential long-term experiments. Since low-priced tickets are not being offered simply to fill houses, but to make tickets more generally accessible, they are bellwethers that can tell us if price is indeed a barrier to theatre attendance, and if, by removing that impediment, theatre can draw in new and younger audiences.

Signature’s can only be studied at some point in the future, as every ticket is low-priced, flat rate and subsidised for years to come. The National reports that annually, 22% of the Travelex tickets are sold to first time attendees. The very early weeks of the Donmar plan shows some 40% of the Front Row seats going to patrons new to their customer rolls.

As the means of selling and acquiring tickets mirror conventional marketplace practices, while at the same time initiatives rise up to spur sales to more demographically and economically differentiated audiences, the matrix of price and value becomes ever more complex. For producers, there is flexibility to adapt as never before. For patrons, the price points can become advantageous or prohibitive. Hopefully, in this new and perpetually evolving world, theatregoing will not be predicated and expanded solely on the cheapest access possible, but on the fundamental and incalculable premise of the art of the theatre itself having meaning for those who seek to attend.

This week, Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman’s 1990 musical Assassins will have its first major New York performances since the 2004 Roundabout Theatre Company production*, in a concert version as part of City Center Encores!’s Off-Center series. Given the controversy sparked last month by The Public Theater’s Julius Caesar, in which Caesar and his wife were portrayed as analogues of Donald and Melania Trump, prompting the withdrawal of sponsors, sparking disruptions of performances and precipitating threats against the production, the theatre, the artists and the staff, it seemed an appropriate moment to speak with Weidman about how Assassins has been perceived over the past 26 years and how the newest incarnation might be received. Weidman, a former president of The Dramatists Guild, currently serves as president of the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, founded to, according to the organization’s website, “advocate, educate and provide a new resource in defense of the First Amendment.” This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This week, Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman’s 1990 musical Assassins will have its first major New York performances since the 2004 Roundabout Theatre Company production*, in a concert version as part of City Center Encores!’s Off-Center series. Given the controversy sparked last month by The Public Theater’s Julius Caesar, in which Caesar and his wife were portrayed as analogues of Donald and Melania Trump, prompting the withdrawal of sponsors, sparking disruptions of performances and precipitating threats against the production, the theatre, the artists and the staff, it seemed an appropriate moment to speak with Weidman about how Assassins has been perceived over the past 26 years and how the newest incarnation might be received. Weidman, a former president of The Dramatists Guild, currently serves as president of the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, founded to, according to the organization’s website, “advocate, educate and provide a new resource in defense of the First Amendment.” This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Sherman: In reading some of the press about the prior productions and some of the commentary, one of the ways in which the show is described is that it’s about, and I’m not quoting here, I’m paraphrasing, it’s about an America that causes people who feel they have no voice to take extreme actions. As we look at politics today, there are those who say that where we are is about people who felt they were disenfranchised from the political system, and that has brought us to the real polarization that we’re at now. Might that affect people’s perceptions?

Sherman: In reading some of the press about the prior productions and some of the commentary, one of the ways in which the show is described is that it’s about, and I’m not quoting here, I’m paraphrasing, it’s about an America that causes people who feel they have no voice to take extreme actions. As we look at politics today, there are those who say that where we are is about people who felt they were disenfranchised from the political system, and that has brought us to the real polarization that we’re at now. Might that affect people’s perceptions?