December 3rd, 2014 § § permalink

Not to dash anyone’s dreams, but I think it’s fair to say that the majority of the hundreds of thousands of students who participate in high school theatre annually will not go on to professional careers in the arts. The same holds true for the student musicians in orchestras, bands and ensembles. They all benefit from the experience in many ways: from the teamwork, the discipline and the appreciation of the challenge and hard work that goes into such endeavors, to name but a few attributes.

But for some students, those high school experiences may be the foundation of a career, of a life, and it’s an excellent place for skills and principles to be taught. As a result, I have, on multiple occasions, heard creative artists talk about their wish that students could learn about the basics of copyright, which can for writers, composers, designers, and others be the root of how they’ll be able to make a life in the creative arts, how their work will reach audiences, how they’ll actually earn a living.

I’m not suggesting that everyone get schooled in the intricacies of copyright law, but that as part of the process of creating and performing shows, students should come to understand that there is a value in the words they speak and the songs they sing, a concept that’s increasingly frayed in an era of file sharing, sampling, streaming and downloading. Creative artists try to make this case publicly from time to time, whether it’s Taylor Swift pulling her music from Spotify over the service’s allegedly substandard rate of compensation to artists or Jason Robert Brown trying to explain why copying and sharing his sheet music is tantamount to theft of his work. But without an appreciation for what copyright protects and supports, it’s difficult for the average young person to understand what this might one day mean to them, or to the people who create work that they love.

* * *

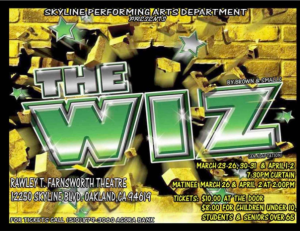

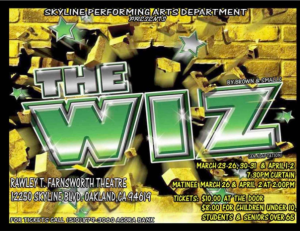

All of this brings me to a seemingly insignificant example, that of a production of the musical The Wiz at Skyline High School in Oakland, California back in 2011. Like countless schools, Skyline mounted a classic musical for their students’ education and enjoyment, in this case playing eight performances in their 900 seat auditorium, charging $10 a head. These facts might be wholly unremarkable, except for one salient point: the school didn’t pay for the rights to perform the show.

All of this brings me to a seemingly insignificant example, that of a production of the musical The Wiz at Skyline High School in Oakland, California back in 2011. Like countless schools, Skyline mounted a classic musical for their students’ education and enjoyment, in this case playing eight performances in their 900 seat auditorium, charging $10 a head. These facts might be wholly unremarkable, except for one salient point: the school didn’t pay for the rights to perform the show.

The licensing house Samuel French only learned this year about the production, and consequently went about the process of collecting their standard royalty. Over the course of a few months, French staff corresponded with school staff and volunteers connected with the drama program, administration and ultimately the school system’s attorney. French’s executive director Bruce Lazarus shared the complete correspondence with me, given my interest in authors’ rights and in school theatre.

I’m very sympathetic to any school that wants to give their students a great arts experience, and so the drama advisor’s discussion in the correspondence of limited resources and constrained budgets really struck me. Oakland is a large district and Skyline is an inner-city school; I have no reason to doubt their concerns about the quoted royalty costs for The Wiz being beyond their means. But their solution to this quandary took them off course.

I’m very sympathetic to any school that wants to give their students a great arts experience, and so the drama advisor’s discussion in the correspondence of limited resources and constrained budgets really struck me. Oakland is a large district and Skyline is an inner-city school; I have no reason to doubt their concerns about the quoted royalty costs for The Wiz being beyond their means. But their solution to this quandary took them off course.

Skyline claims that they did their own “adaptation” of The Wiz, securing music online and assembling their own text, under the belief that this released them from any responsibility to the authors and the licensing house. While they tagged their ads for the show with the word “adaptation,” it’s a footnote, and if one looks at available photos or videos from the production, it seems pretty clear that their Wiz is firmly rooted in the original material, even the original Broadway production. Surely the text was a corruption of the original and perhaps songs were reordered or even eliminated. It’s also worth noting that Skyline initially inquired about the rights, but then opted to do the show without an agreement.

* * *

OK, so one school made a mistake over three and a half years ago – what’s the big deal? That brings me to the position taken by the Oakland Unified School District regarding French’s pursuit of appropriate royalties. OUSD has completely denied that French has any legitimate claim per their attorney, Michael L. Smith. In a mid-October letter, Mr. Smith cites copyright law statute of limitations, saying that since it has been more than three years since the alleged copyright violation, French is “time barred from any legal proceeding.” Explication of that position constitutes the majority of the letter, save for a phrase in which Mr. Smith states, “As you are likely aware, there are limitations on exclusive rights that may apply in this instance, including fair use.”

As I’m no attorney, I can’t research or debate the fine points of statutes of limitation, either under federal or California law. However, I’ve read enough to understand that there’s some disagreement within the courts, as to when the three-year clock begins on a copyright violation. It may be from the date of the alleged infringement itself, in this case the date of the March and April 2011 performances, but it also may be from the date the infringement is discovered, which according to French was in September 2014. We’ll see how that plays out.

The passing allusion to fair use provisions is perhaps of greater interest in this case. Fair use provides for the utilization of copyrighted work under certain circumstances in certain ways. Per the U.S. Copyright office:

Copyright Law cites examples of activities that courts have regarded as fair use: “quotation of excerpts in a review or criticism for purposes of illustration or comment; quotation of short passages in a scholarly or technical work, for illustration or clarification of the author’s observations; use in a parody of some of the content of the work parodied; summary of an address or article, with brief quotations, in a news report; reproduction by a library of a portion of a work to replace part of a damaged copy; reproduction by a teacher or student of a small part of a work to illustrate a lesson; reproduction of a work in legislative or judicial proceedings or reports; incidental and fortuitous reproduction, in a newsreel or broadcast, of a work located in the scene of an event being reported.”

* * *

Rather than parsing the claims and counterclaims between Samuel French and the school district, I consulted an attorney about fair use, though in the abstract, not with the specifics of the show or school involved. I turned to M. Graham Coleman, a partner at the firm of Davis Wright Tremaine in their New York office. Coleman works in all legal aspects of live theatre production and counsels clients on all aspects of copyright and creative law. He has also represented me on some small matters.

“In our internet society, “ said Coleman, “there is a distortion of fair use. We live in a world where it’s so easy to use someone’s proprietary material. The fact that you based work on something else doesn’t get you off the hook with the original owner.”

Without knowing the specifics of Skyline’s The Wiz, Coleman said, “They probably edited, they probably varied it, but they probably didn’t move it into fair use. Taking a protectable work and attempting to ‘fair use’ it is not an exercise for the amateur.”

Regarding the language in fair use rules that cite educational purposes, Coleman said, “Regardless of who you are, once you start charging an audience admission, you’re a commercial enterprise. Educational use would be deemed to mean classroom.”

While Coleman noted that the cost of pursuing each and every copyright violation by schools might be cost prohibitive for the rights owners, he said that, “It becomes a matter of principle and cost-effectiveness goes out the window. They will be policed. Avoiding doing it the bona fide way will catch up with you.”

* * *

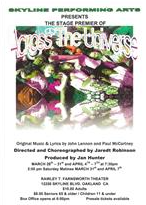

That’s where the Skyline scenario gets more complicated – because their “adaptation” of The Wiz wasn’t their only such appropriation of copyrighted material. In 2012, the school produced a stage version of Julie Taymor’s Beatles-inspired film Across The Universe, billing it accordingly and crediting John Lennon and Paul McCartney as the songwriters. The problem is, there is no authorized stage adaptation of the film, although there have been intermittent reports that Taymor is contemplating her own, which her attorney affirmed to me. In this case, the Skyline production is still within the statute of limitations for a copyright claim.

That’s where the Skyline scenario gets more complicated – because their “adaptation” of The Wiz wasn’t their only such appropriation of copyrighted material. In 2012, the school produced a stage version of Julie Taymor’s Beatles-inspired film Across The Universe, billing it accordingly and crediting John Lennon and Paul McCartney as the songwriters. The problem is, there is no authorized stage adaptation of the film, although there have been intermittent reports that Taymor is contemplating her own, which her attorney affirmed to me. In this case, the Skyline production is still within the statute of limitations for a copyright claim.

I attempted to contact both the principal of Skyline High and the superintendent of the school district about this subject, ultimately reaching the district’s director of communications Troy Flint. In response to my questions about The Wiz, Flint said, “We believe that we were within our rights. I can’t go into detail because I’m not prepared to discuss our legal strategy. We believe this use was permissible.”

I attempted to contact both the principal of Skyline High and the superintendent of the school district about this subject, ultimately reaching the district’s director of communications Troy Flint. In response to my questions about The Wiz, Flint said, “We believe that we were within our rights. I can’t go into detail because I’m not prepared to discuss our legal strategy. We believe this use was permissible.”

He couldn’t speak to Across The Universe; it seemed that I may have been the first to bring it to the district’s attention. Flint said he didn’t know whether other Skyline productions, such as Hairspray and Dreamgirls, had been done with licenses from rights companies, although I was able to confirm independently that Hairspray was properly licensed. Which raises the question of why standard protocol for licensing productions was followed with some shows and not others.

* * *

My fundamental interest is in seeing vital and successful academic theatre. So while their identities are easily accessible, I’ve avoided naming the teacher, principal and even the superintendent at Skyline because I don’t want to make this one example personal. But I do want to make it an example.

Whether or not I, or anyone, personally agree with the provisions of U.S. copyright law isn’t pertinent to this discussion, and neither is ignorance of the law. The fact is that the people who create work (and their heirs and estates) have the right to control and benefit from that work during the copyright term. Whether the content is found in a published script and score, shared on the internet or transcribed from other media, the laws hold.

If the Skyline examples were the sole violations, a general caution would be unnecessary, but in the past three months alone, Samuel French has discovered 35 unlicensed/unauthorized productions at schools and amateur companies, according to the company’s director of licensing compliance Lori Thimsen. Multiply that out over other rights houses, and over time, and the number is significant. This even happens at the professional level.

At the start, I suggested that students should know the basic of copyright law, both out of respect for those who might make their careers as creative artists, as well as for those who will almost certainly be consumers of copyrighted content throughout their lives. But it occurs to me that these lessons are appropriate for their teachers as well, notwithstanding the current legal stance at Skyline High. There can and should be appreciation for creators’ achievements as well as their rights, and appropriate payment for the use of their work – and those who regularly work with that material should make absolutely certain they know the parameters, to avoid and prevent unwitting, and certainly intentional, violations.

* * *

One final note: some of you may remember Tom Hanks’s Oscar acceptance speech for the film Philadelphia, when he paid tribute to his high school drama teacher for playing a role in his path to success. It might interest you to know that Hanks attended Skyline High and thanks in part to a significant gift from him, the school’s theatre – where the shows in question were performed – was renovated and renamed for that teacher, Rawley Farnsworth, in 2002. Hanks also used the occasion of the Oscars to cite Farnsworth and a high school classmate as examples of gay men who were so instrumental in his personal growth.

I have no doubt that there are other such inspirational teachers and students at Skyline High today, perhaps working in the arts there under constrained budgets and resources. Yet regardless of statutes of limitations, it seems that the Rawley T. Farnsworth Theatre should be a place where respect for and responsibility to artists is taught and practiced, as a fundamental principle – and where students get to perform works as their creators intended, not as knockoffs designed to save money.

* * *

Update, December 3, 2014, 4 pm: This post went live at at approximately 10:30 am EST this morning. I received an e-mail from OUSD’s director of communications Troy Flint at approximately 1 pm asking whether the post was finished and whether he could add to his comments from yesterday. I indicated that the post was live and provided a link, saying that I have updated posts before and would consider an addendum with anything I found to be pertinent. He just called to provide the following statement, which I reproduce in its entirety.

Whatever the legality of the situation at Skyline regarding The Wiz and Across The Universe, the fundamental principle is that we want the students to respect artists’ work and what they put into the product. My understanding is that Skyline’s use of this material is legally defensible, but that’s not the best or highest standard.

As we help our students develop artistically, we want to make sure they have the proper respect and understanding of the work that’s involved with creating a play for the stage or the cinema. So we have spoken with the instructors at Skyline about making sure they follow all the protocols regarding rights and licensing, because we don’t want to be in a position of having the legality of one of our productions questioned as they are now and we don’t want to be perceived as taking advantage of artists unintentionally as we are now. It’s not just a legal issue but an issue of educating students properly.

While everyone I have spoken with about this issue disagrees fairly strenuously with the opinion of the OUSD legal counsel, it’s encouraging that the district wants to stand for artists’ rights and avoid this sort of conflict going forward. I hope they will ultimately teach not only the principle, but the law. As for past practice, I leave that to the lawyers.

Update, December 3, 2014, 7 pm: Following my update with the statement from the school district, I received a statement of response from Bruce Lazarus, executive director of Samuel French. It is excerpted here.

By withholding the proper royalty for The Wiz from the authors, the OUSD is communicating to their students that artistic work is worthless. Is this an appropriate message for any budding artist? That you too can grow up to write a successful musical…only to then have a school district destroy your work and willfully withhold payment?

It needs to be made clear to the OUSD and the students involved that an artist’s livelihood depends on receiving payment for their creative work. This is how artists make a living. How they pay the rent and feed their families. It is simply unbelievable that this issue can be tossed aside with an “Our bad, won’t happen again” response without consideration of payment for their unauthorized taking of another’s property.

Are other students of the OUSD, those that are not artists, being educated to expect payment for their services rendered when they presumably become doctors, engineers, entrepreneurs and the next leaders of the Bay Area? Of course they are. And so it goes for the artists in your classrooms, who should be able to grow up KNOWING there is protection for their future work and a real living wage to be made.

Equal time granted, I leave it the respective parties to resolve the issue of what has already taken place.

November 4th, 2013 § § permalink

It’s not unusual for book releases to be coordinated with a related event taking place elsewhere in the media circus: the autobiography that appears just as a star’s major film is coming out, the personal memoir that primes the public for a political campaign. However, no one can accuse Julie Taymor of engaging in such wanton promotion – she certainly can’t be pleased that Glen Berger’s Song of Spider-Man: The Inside Story of the Most Controversial Musical in Broadway History (Simon & Schuster, $25) debuts just as she returns to the stage with A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Theatre for a New Audience in Brooklyn. One imagines she’d have been happier if there were no book at all.

Countless people are reading and writing about the book as another chapter in the seemingly never-ending saga of Spider-Man: Turn Off The Dark, the headline generating musical that has been the target of brickbats from arts journalists virtually since the show was first announced. Spider-Man: TOTD seemed to throw raw meat to the media at every turn, ranging from fundraising challenges and production delays to several highly publicized cast injuries which seemed to turn the show into a latter-day Roman arena. It kept Patrick Healy of the Times and Michael Riedel of the Post in competition for breaking tidbits in a manner rarely seen before.

I didn’t find Berger’s book particularly revealing, largely because it covers ground that had been extensively reported elsewhere, and I confess to having consumed the events as they happened. In fact, I made a point of seeing the very final performance of the Taymor version and the opening night of the version reworked without her – and, for the most part, Berger’s – consent, after they had been supplanted by Philip William McKinley and Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa respectively. Yes, I watched the show’s travails, as most did, as a theatrical car wreck in slow motion, a modern-day tragedy of creative hubris played played out in benday dots and rock chords.

I didn’t find Berger’s book particularly revealing, largely because it covers ground that had been extensively reported elsewhere, and I confess to having consumed the events as they happened. In fact, I made a point of seeing the very final performance of the Taymor version and the opening night of the version reworked without her – and, for the most part, Berger’s – consent, after they had been supplanted by Philip William McKinley and Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa respectively. Yes, I watched the show’s travails, as most did, as a theatrical car wreck in slow motion, a modern-day tragedy of creative hubris played played out in benday dots and rock chords.

For all that Berger recounts, the book constantly reminds the reader that it is the story of Spider-Man: TOTD as viewed through one person’s biased eyes – rather than the whole story. Berger goes out of his way to paint himself as a innocent caught up in the maelstrom of vastly more famous, and vastly wealthier, artists than himself. His emphasis on being separated from his family, of his personal financial troubles, of how different his world is from that of his acclaimed and wealthy collaborators Bono and Taymor – they grow tiresome, as if Berger deserves some sympathy or absolution for his role in the debacle by virtue of his less lofty perch. But he’s not exactly Nick Carraway observing the actions of Gatsby and the Buchanans – he’s a willing participant until his own calculations backfire on him, severing his ties forever with Taymor, who he has built up as his own artistic Daisy. To compare him to Faust conveys a grandeur I decline to confer.

The fact is, reading Berger’s book is like watching only one viewpoint from Rashomon, and one is all too aware that others undoubtedly have very different versions of the same events. I can’t help but suspect that the musical might at best be a page or two should Bono write his life story; producer Michael Cohl would no doubt recount the saga as a story of how he rescued a damaged show that most believed was dead on arrival; should Taymor tell her version, it will be of an artist (herself) persecuted by greedy philistines. Whether anyone will care to follow the tale repeatedly refracted through varying prisms is anyone’s guess, though that might be the only way to get the real story.

All of this should not suggest that Berger’s book has no value. It is, at the very least, a superb answer to the perennial question about troubled or failed shows: “Didn’t anyone realize how bad it was going to be?” The book is an encyclopedia of ignorance, ego and self-delusion, a look at how a theatrical property, especially one with such a high profile, almost becomes unstoppable, and the many ways in which it can go wrong, of how perspective is lost when you are so close to the work for so long. Aspiring producers should read it as a cautionary tale – not about a one-off disaster, but rather about when it pays to just say no, shut a show down, and move on, since Spider-Man may be the most expensive show to date, but there are plenty of complete flops that followed much the same misguided path.

Inevitably, Berger’s book will find its way onto many a theatrical bookshelf, even if it doesn’t have the elegance or educational value of many other books with which it shares conceptual and theatrical DNA. As I read it, I was reminded of a book about a vastly less well known disaster: playwright Arnold Wesker’s The Birth of Shylock, The Death of Zero Mostel, a chronicle of a quick Broadway flop notable mostly for the death of Mostel, its leading actor, who died while the show was trying out in Philadelphia. Like Berger, Wesker seems almost entirely unaware of his own complicity in the show’s failure, even as he repeatedly tells about his taking aside actors to countermand the edicts of the show’s director, John Dexter. Shylock the show is in the dustbin of Broadway history, whereas the legend of Spider-Man will surely go on; however, the author’s account of the production of Shylock makes for better literature than Song of Spider-Man.

Inevitably, Berger’s book will find its way onto many a theatrical bookshelf, even if it doesn’t have the elegance or educational value of many other books with which it shares conceptual and theatrical DNA. As I read it, I was reminded of a book about a vastly less well known disaster: playwright Arnold Wesker’s The Birth of Shylock, The Death of Zero Mostel, a chronicle of a quick Broadway flop notable mostly for the death of Mostel, its leading actor, who died while the show was trying out in Philadelphia. Like Berger, Wesker seems almost entirely unaware of his own complicity in the show’s failure, even as he repeatedly tells about his taking aside actors to countermand the edicts of the show’s director, John Dexter. Shylock the show is in the dustbin of Broadway history, whereas the legend of Spider-Man will surely go on; however, the author’s account of the production of Shylock makes for better literature than Song of Spider-Man.

While there are certainly great Broadway books of autobiography (Moss Hart’s Act One is an exemplar of the kind), more often than not the best chroniclers are those on the fringes or outside of a production entirely. Ted Chapin’s Everything Was Possible: The Birth of the Musical ‘Follies’ is an impeccable recent example of the former, derived from Chapin’s own notes as a production assistant on the original Follies; William Goldman’s The Season: A Candid Look At Broadway has long stood as a grand achievement of the latter. Of course, in both cases, the authors were given rare access, which seems almost impossible in the more media savvy world of today; the film industry was reminded about the danger of giving journalism too much access when critic Julie Solomon roamed free on the set of a Brian DePalma film, resulting in The Devil’s Candy: Anatomy of a Hollywood Fiasco, a detailed chronicle of the famous flop The Bonfire of the Vanities.

While there are certainly great Broadway books of autobiography (Moss Hart’s Act One is an exemplar of the kind), more often than not the best chroniclers are those on the fringes or outside of a production entirely. Ted Chapin’s Everything Was Possible: The Birth of the Musical ‘Follies’ is an impeccable recent example of the former, derived from Chapin’s own notes as a production assistant on the original Follies; William Goldman’s The Season: A Candid Look At Broadway has long stood as a grand achievement of the latter. Of course, in both cases, the authors were given rare access, which seems almost impossible in the more media savvy world of today; the film industry was reminded about the danger of giving journalism too much access when critic Julie Solomon roamed free on the set of a Brian DePalma film, resulting in The Devil’s Candy: Anatomy of a Hollywood Fiasco, a detailed chronicle of the famous flop The Bonfire of the Vanities.

Though it covers work which is vastly less infamous and some 50 years in the past, I daresay that Jack O’Brien’s recent Jack Be Nimble: The Accidental Education of an Unintentional Director (Farrar Straus and Giroux, $35) is the more worthy, entertaining and educational insider theatre book of the year. While O’Brien could have easily produced a standard memoir, given his own considerable achievements as a director, he followed Chapin’s lead and instead opted to write about the access he had as a young man to a remarkable confluence of talents: the members of the APA and later the APA-Phoenix theatre companies, which included Richard Easton, Rosemary Harris and above all the now little-remembered Ellis Rabb. I know firsthand what a wealth of stories Jack can tell about his own exploits, but by deciding to honor the artists who formed his own aesthetic, he has written a work of history and memoir that is ultimately more important and informative than Berger’s attempt to make a few more dollars off the Spider-Man debacle.

Though it covers work which is vastly less infamous and some 50 years in the past, I daresay that Jack O’Brien’s recent Jack Be Nimble: The Accidental Education of an Unintentional Director (Farrar Straus and Giroux, $35) is the more worthy, entertaining and educational insider theatre book of the year. While O’Brien could have easily produced a standard memoir, given his own considerable achievements as a director, he followed Chapin’s lead and instead opted to write about the access he had as a young man to a remarkable confluence of talents: the members of the APA and later the APA-Phoenix theatre companies, which included Richard Easton, Rosemary Harris and above all the now little-remembered Ellis Rabb. I know firsthand what a wealth of stories Jack can tell about his own exploits, but by deciding to honor the artists who formed his own aesthetic, he has written a work of history and memoir that is ultimately more important and informative than Berger’s attempt to make a few more dollars off the Spider-Man debacle.

Perhaps, one day, a young PA on Spider-Man: TOTD will emerge with his or her own book, to draw the truest picture of what went on as the web collapsed. Until then, we’re left with a lopsided recap of a story that we mostly know, told by what is called, in literary circles, an unreliable narrator.

September 12th, 2013 § § permalink

Macbeth. Twelfth Night. Richard III. Romeo and Juliet. No Man’s Land. Waiting For Godot. Betrayal. The Winslow Boy.

The syllabus for a university survey course in drama? No. Instead, it’s the roster of eight of the 16 titles scheduled to open on Broadway between now and the end of 2013.

To be sure, British plays, artists and productions haven’t ever been strangers to Broadway, but this preponderance of works – featuring actors such as Jude Law, Mark Rylance, Rachel Weisz, Daniel Craig, Anne-Marie Duff, Stephen Fry, Orlando Bloom, Roger Rees, Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart – in the 40 theatres that comprise Broadway, all at the same time, is an embarrassment of riches. Add in concurrent Off-Broadway productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream with David Harewood and Kathryn Hunter (opening the new Theatre for a New Audience space in Brooklyn) and Michael Gambon and Eileen Atkins in All That Fall, and it appears that Anglophilia is running rampant in the playhouses of New York.

Much of this is coincidence, since it’s not as if producers conspire on themes. Indeed, from a marketing standpoint, it’s not necessarily even a good idea, since the theatregoers most drawn to this work may have to face some tough buying decisions unless they have unlimited resources and time. Cultural tourists won’t even be able to fit all of these terrific sounding shows in, should they fly to the city for merely a long weekend.

But whether the productions are transfers from the UK or newly minted in America, as is the case with No Man’s Land, Romeo and Juliet, and Betrayal, the British imprimatur seems as if it’s a requirement this year, even if only in part. UK director David Leveaux is staging Romeo and Juliet with a North American cast capped by Bloom. US director Julie Taymor tapped Harewood and Hunter for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, her first project since the highly-publicised and contentious Spiderman: Turn Off The Dark (a tell-all book by her collaborator Glen Berger will be released just as Midsummer performances begin). Even the US classic The Glass Menagerie is being helmed by John Doyle. Only Classic Stage Company’s Romeo and Juliet, with Elizabeth Olsen and TR Knight, is wholly comprised of American artists, though their Romeo is Japan-born.

The English theatre can certainly take pride in this abundance of talent exported to American shores, and I look forward to each and every one of these shows enthusiastically. Indeed, I’ll pass on my annual autumn trip to London since I’ll need only take the subway and not British Airways.

But it does beg the question of whether classical work can succeed on Broadway without a UK connection. Are producers giving up on our best American actors and directors taking on British and Irish pieces without at least some of that heritage in the shows’ DNA? To be sure, not-for-profit companies may lean American overall (LCT’s Macbeth is Ethan Hawke), but has public television conditioned us to desire the “genuine” article? Great American plays appear on British stages frequently, ranging from A View From The Bridge to Fences to Clybourne Park, without the perpetual need to import Americans, let alone the cream of American talent, to make them work. Yet the power of UK casting appears to be such that even multiple Macbeths are deemed economically viable, with Alan Cumming having played virtually all of the roles on Broadway only months ago and Kenneth Branagh due at the Park Avenue Armory in June 2014.

I don’t like calling attention to national divisions when it comes to art, but the fall theatre season in New York simply can’t be overlooked. Despite the luxury of all of the great theatre on tap, the timing sends the message to US actors, theatre students, critics and audiences that when it comes to staging foreign classics, the talent exchange flows more strongly from west to east than in the other direction.

But looking on the bright side, perhaps this means we’ll soon enjoy one more benefit of the English stage, and be able to buy ice cream at the interval.

May 13th, 2012 § § permalink

Gender and racial diversity in the arts has been a topic of discussion for as long as I can remember. But the ongoing inequities in the American theatre have been simmering for a long time. Intermittent signs of progress – Garry Hynes and Julie Taymor winning Tonys in 1997, dual firsts for women; the rich cycle of plays by August Wilson that brought a black voice to Broadway and stages across the country; the current Broadway season which featured two new plays by black female writers – are received with attention and even acclaim. Yet overall, there is general consensus that these constituencies are profoundly underrepresented.

While dissatisfaction can be directed at the commercial theatre, it is decentralized; each production is its own corporate entity and producers do not consult with all of the other producers. When it comes to new plays, as it happens, a majority of the work seen on Broadway (if not from England) has emerged from not-for-profit companies. Consequently, the publicly-funded resident theatres have become the locus of attention on these issues and, accelerated by social media, the continuing lack of meaningful process may be coming to a head.

The underrepresentation of women and racially-diverse authors on our stages has come into sharp relief recently as a result of the season announcement by The Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis, one of our oldest and largest companies. In announcing a season of 11 productions thus far, there are no plays by female playwrights (although a Goldoni adaptation is by Constance Congdon), no plays by any writers of color, and only one project with a female director (more accurately, a co-director, with Mark Rylance). In the outcry that ensued, it was noted that almost 10 years ago, while rallying support and funding for The Guthrie’s new home, Dowling had specifically said the new venue would allow for a greater variety of voices; responding to current criticism, he stoked the flames by invoking and decrying “tokenism.”

This prominent example generated press coverage beyond the Minneapolis-St. Paul market, let alone an ongoing rumble of dismay across blogs and Twitter. Perhaps it was Dowling’s defensiveness that made The Guthrie situation so volatile. After all, this past season, Chicago’s acclaimed Steppenwolf Theatre mainstage season featured plays only by men (one an African American), and this from a theatre with a female artistic director; I don’t remember comparable outcry. Was this tempered by the season including several female directors? Or has the Guthrie flap made it easier to raise these issues?

Now each new season announcement is being held up to an accounting, not necessarily in its own board room, staff meeting or local press, but by activists seeking to lay bare this congenital issue. In 2012-13? Arizona Theatre Company: Six plays, all by white males. Seattle Rep: Eight plays, two by women, one of them African American. Alley Theatre in Houston: 11 productions, 2 by women (one of them Agatha Christie) and one by an Asian American man. Kansas City Rep: seven shows, six by men and one developed by an ensemble. Obviously I cannot go theatre by theatre, and I think more detailed data will be gathered, but underrepresentation of works by women and writers of color (of any gender) prevails. What of Steppenwolf? Their next five play season includes plays by one woman and one African-American man.

Is it fair to apply what some might call a quota system in assessing the diversity work on American stages? I would have to say, as so many of our resident theatres are on the verge of celebrating their 50th anniversaries in the next few years, that a public declaration of these figures is not only fair, but necessary. Theatres have been asked by foundations, by corporations, by government funders to break down their staffs and boards by gender and race for years, and knowing that they were under scrutiny may have caused many companies to diversify internally more, or more quickly, than they might have otherwise. Actors Equity has conducted surveys of seasonal hiring, broken down for gender and race, for a number of years – another watchful eye. Now the focus must shift to the writers of the work on our stages if progress is to be made.

It is ironic that the civil rights movement in America is perhaps most associated with the 1960s, followed closely by the feminist movement — the very same period that coincidentally also saw the bourgeoning of the American resident theatre movement. How unfortunate that some of the language associated, for good or ill, with the first two efforts (tokenism, quotas) are even relevant in discussion of artistic breadth of the latter half a century later.

All of this brings me to a seemingly insignificant example, that of a production of the musical The Wiz at Skyline High School in Oakland, California back in 2011. Like countless schools, Skyline mounted a classic musical for their students’ education and enjoyment, in this case playing eight performances in their 900 seat auditorium, charging $10 a head. These facts might be wholly unremarkable, except for one salient point: the school didn’t pay for the rights to perform the show.

All of this brings me to a seemingly insignificant example, that of a production of the musical The Wiz at Skyline High School in Oakland, California back in 2011. Like countless schools, Skyline mounted a classic musical for their students’ education and enjoyment, in this case playing eight performances in their 900 seat auditorium, charging $10 a head. These facts might be wholly unremarkable, except for one salient point: the school didn’t pay for the rights to perform the show. I’m very sympathetic to any school that wants to give their students a great arts experience, and so the drama advisor’s discussion in the correspondence of limited resources and constrained budgets really struck me. Oakland is a large district and Skyline is an inner-city school; I have no reason to doubt their concerns about the quoted royalty costs for The Wiz being beyond their means. But their solution to this quandary took them off course.

I’m very sympathetic to any school that wants to give their students a great arts experience, and so the drama advisor’s discussion in the correspondence of limited resources and constrained budgets really struck me. Oakland is a large district and Skyline is an inner-city school; I have no reason to doubt their concerns about the quoted royalty costs for The Wiz being beyond their means. But their solution to this quandary took them off course. That’s where the Skyline scenario gets more complicated – because their “adaptation” of The Wiz wasn’t their only such appropriation of copyrighted material. In 2012, the school produced a stage version of Julie Taymor’s Beatles-inspired film Across The Universe, billing it accordingly and crediting John Lennon and Paul McCartney as the songwriters. The problem is, there is no authorized stage adaptation of the film, although there have been intermittent reports that Taymor is contemplating her own, which her attorney affirmed to me. In this case, the Skyline production is still within the statute of limitations for a copyright claim.

That’s where the Skyline scenario gets more complicated – because their “adaptation” of The Wiz wasn’t their only such appropriation of copyrighted material. In 2012, the school produced a stage version of Julie Taymor’s Beatles-inspired film Across The Universe, billing it accordingly and crediting John Lennon and Paul McCartney as the songwriters. The problem is, there is no authorized stage adaptation of the film, although there have been intermittent reports that Taymor is contemplating her own, which her attorney affirmed to me. In this case, the Skyline production is still within the statute of limitations for a copyright claim. I attempted to contact both the principal of Skyline High and the superintendent of the school district about this subject, ultimately reaching the district’s director of communications Troy Flint. In response to my questions about The Wiz, Flint said, “We believe that we were within our rights. I can’t go into detail because I’m not prepared to discuss our legal strategy. We believe this use was permissible.”

I attempted to contact both the principal of Skyline High and the superintendent of the school district about this subject, ultimately reaching the district’s director of communications Troy Flint. In response to my questions about The Wiz, Flint said, “We believe that we were within our rights. I can’t go into detail because I’m not prepared to discuss our legal strategy. We believe this use was permissible.”