A theatre scene performed al fresco on a spring Florida evening sounds idyllic. But when Tomas Roldan and Matthew Ferro, juniors at New World School of the Arts High School, took their award-winning scene from Stephen Adly Guirgis’s The Last Days of Judas Iscariot to a plaza outside the Florida State Thespian Festival in Tampa on March 28, they weren’t doing so seeking charm or fresh air. They made the performance choice as a third option after being given two official choices by festival leadership: alter Guirgis’s words or don’t perform at all.

* * *

The Florida State Thespian Festival is the largest such gathering in the country. Over a long weekend, high school students gather for talks, workshops and competitions all focused on theatre; in Florida, there are more than 7,000 people in attendance from the large state’s 16 designated districts. This year’s festival included full productions of, among others, Ragtime, The Great Gatsby, Night of the Living Dead, The Threepenny Opera, Violet, Pippin, and Seascape; there was even a concert by The Skivvies, the musical theatre duo known for their talent, their wit and their commitment to performing in their underwear.

Woven throughout the festival are the competitions, where students from schools across the state perform short scenes from a wide range of shows, assembled into groups of competitors so that one set of adjudicators can make decisions on those competing in that defined grouping; the festival is simply too large, and too brief, to allow for an American Idol-type winnowing to a single champion, so each group produces its own winners. Ferro and Roldan received a Critic’s Choice honor for their scene between Jesus and Judas from Guirgis’s play, which Roldan said had been their goal from the time he and Ferro started working on their scene, nearly a year earlier.

The winners of Critic’s Choice in each group are invited to perform in the Critic’s Choice Showcase on the final evening of the festival. Given the number of winners, it is held in segments (or acts) throughout Saturday night in the largest venue used by the festival, the Straz Center’s main hall, seating nearly 3,000. The audience is made up of students, teachers, parents and family. Because competitions are happening on a rolling basis throughout the weekend, the run of the evening is still coming together even as the first performers come to the stage at 6 pm.

The winners of Critic’s Choice in each group are invited to perform in the Critic’s Choice Showcase on the final evening of the festival. Given the number of winners, it is held in segments (or acts) throughout Saturday night in the largest venue used by the festival, the Straz Center’s main hall, seating nearly 3,000. The audience is made up of students, teachers, parents and family. Because competitions are happening on a rolling basis throughout the weekend, the run of the evening is still coming together even as the first performers come to the stage at 6 pm.

* * *

It is the policy of the Educational Theatre Association, which runs the International Thespian Society, not to censor the work of writers. The director of the Florida chapter, Linday M. Warfield Painter, echoed that sentiment, saying, “I don’t condone the changing of a playwright’s language any more than the next person.”

In Florida, students competing with scenes that may have potentially controversial or even offensive content are asked to “asterisk” their scenes, noting what some might find problematic. This doesn’t preclude their competing, but serves as notice for those attending the competitive rounds that if they wish to avoid such material, they should step out before the scene is performed. Roldan and Ferro’s scene was duly asterisked for its language – the scene contains iterations of the word “fuck” some dozen times – and for its contemporary portrayal of religious figures Jesus and Judas. The Florida guidelines also require that school principals sign off on the choice of scenes to be performed by their students – except for schools in Miami-Dade County, where a teacher’s approval is sufficient. New World School of the Arts High School is part of the New World School of the Arts, an arts university in Miami affiliated with Miami-Dade College and the University of Florida.

The asterisk system, implemented less than a decade ago partly in response to consternation at the state capitol over content seen at the festival, apparently works well enough in the many small competition rooms, but it becomes problematic, and even irrelevant, at the critics choice showcase. Given the size of the theatre and the numerous brief scenes being performed, the policy is that the audience cannot come and go as they please, so there isn’t a steady attrition of audience once the students they come to see have completed their scenes. If an audience member exits at any point during one of the acts, there is no readmission. So it’s not feasible to offer the audience the opportunity to leave if a scene might offend them, leaving the asterisk process in the dust.

As a result, after winning in their group, the winners have to perform one more time, for adjudicators who will determine whether the scene is appropriate for the large audience. That’s where Roldan and Ferro said they were surprised.

“They knew our piece was asterisked for religious content and for language,” recalls Roldan. “They asked us how severe the language was and we said we drop, we have a few f-bombs in there. Then they told us OK – well we’ll listen to it and tell you what we can do about the language. So we performed the scene again and they told us, ‘Wow, that’s a really great scene, except you guys curse way too much and there’s too many f-bombs in the piece. So you guys have to fully, completely clean it up or you wouldn’t be able to perform it’.”

“They knew our piece was asterisked for religious content and for language,” recalls Roldan. “They asked us how severe the language was and we said we drop, we have a few f-bombs in there. Then they told us OK – well we’ll listen to it and tell you what we can do about the language. So we performed the scene again and they told us, ‘Wow, that’s a really great scene, except you guys curse way too much and there’s too many f-bombs in the piece. So you guys have to fully, completely clean it up or you wouldn’t be able to perform it’.”

Ferro, interviewed separately, described the process similarly, saying, “We performed it for the two people who were running the show, the Critics Choice show. And it was almost right then and there that they were like ‘We love the piece, we really do. But the language is an issue.’ From the get go, those two people, Ed and I think it was Amy, said ‘We’re going to fight for you. We want you guys to perform this, but we have to find a way.’ So originally they gave us options like changing the language; then it was how about we perform at the very end and we’re going to caution people about our content. Then it was like, ‘We’re going to roll the dice and we’re going to ask our bosses what they think we can do’.”

Both Ferro and Roldan say they were urged to get dinner while the issue was explored, which they did. “When we came back,” continued Ferro, “they had already spoken with their bosses, the person who was running the whole thing and they told me and Tomas that we could not perform with the language. We had to change it or just go on stage and tell them that we couldn’t.”

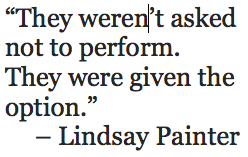

In response to an inquiry about what transpired, Painter said, “I wasn’t in the screening room for this event. I had entrusted other volunteers within the organization to do that for me and they had asked, ‘We’ve got 12 f-bombs dropped in the piece.’ I can see why the two teachers screening it said, ‘Guys, can we clean that up a little bit just for this one moment [the showcase].’ I don’t think that has been – I’m positive that’s not the first time that’s happened, that they’ve been asked to clean up language. As far as whether or not a piece – they weren’t asked not to perform. They were given the option, so it wasn’t like, ‘No, you have bad language, you may not perform.’ The option was there.”

Asked to clarify who is in attendance at the showcase, Painter explained that it is not a public event per se. “We have a mixed crowd as far as different communities from across the state,” she said. “We have Christian schools, we have private schools, we have different schools that are from more conservative communities across the state that are all packed into the 2800 people house. That’s really the reason that we do any kind of screening. And the screening is just, that’s all they’re looking for, if it is an asterisked piece, what is it asterisked for? If it’s something that it’s a simple matter of staging that we could restage really quickly without compromising the integrity of the acting and all that. This piece was probably, had I known ahead of time, that the judges did not give us an alternate, I probably would have suggested it not even necessarily be – just to save them the heartache of having to go through that moment. It’s just because of the content, there’s so much of the language issue with it.

Asked to clarify who is in attendance at the showcase, Painter explained that it is not a public event per se. “We have a mixed crowd as far as different communities from across the state,” she said. “We have Christian schools, we have private schools, we have different schools that are from more conservative communities across the state that are all packed into the 2800 people house. That’s really the reason that we do any kind of screening. And the screening is just, that’s all they’re looking for, if it is an asterisked piece, what is it asterisked for? If it’s something that it’s a simple matter of staging that we could restage really quickly without compromising the integrity of the acting and all that. This piece was probably, had I known ahead of time, that the judges did not give us an alternate, I probably would have suggested it not even necessarily be – just to save them the heartache of having to go through that moment. It’s just because of the content, there’s so much of the language issue with it.

“I can tell you that my community I’ve gotten away with all sorts of shows at my school, I’ve done Rent and Threepenny Opera and Cabaret, even my community wouldn’t be OK with a bunch of f-bombs being dropped on stage. It’s a tough one.” At another point, she said, “For that general audience, they were asked to remove at least a few of the f-bombs to take it down from a “rated R” to at least as PG or PG-13 for the general audience. And they refused to do so, which is their prerogative and their right as artists. I respect that, but we couldn’t out it on our stage in front of a general audience.”

Recalling the scene backstage, as she argued on behalf of the students, one of Ferro and Roldan’s teachers, Annie McAdams, recalls one of the adjudicators for the Showcase saying to her, “’Look, it’s just the word “fucking,” we can’t have “fucking” on this stage, it’s too big a house.’ I said, ‘That doesn’t make sense, how come we have asterisks? What if they say we can let the lights up and everyone can leave if they don’t like it?’ And they said, ‘No, we can’t do it. It’s OK in the little rooms, but it’s not OK in this big room.’ Oh, and they also said that the adjudicators know that and they are not supposed to advance material that will be offensive, they are not supposed to do this. Then I said, ‘Well why do we have that policy if it doesn’t matter? Why do we say that they can do this material if in fact they’re not going to get advanced, they’re not going to be considered?’ So how many other students haven’t been considered? And they never knew.”

* * *

Michael Higgins was the director of the Florida State Thespians for approximately 17 years (he didn’t recall exactly); his tenure concluded in 2010 and Lindsay Painter’s began in 2013. Last week, he spoke of what was happening with the language in competing scenes when he first took on his role. He had not attended the 2015 Festival.

“At the time it was not regulated as far as any kind of censorship issue,” said Higgins. “Then, as all things do, it became more and more of an issue as students were choosing that adult material and more than that it was getting inordinate positive response by the judges. My feeling at the time was since you were trying to get a monologue performed in two minutes, oddly enough the shock words gave you more punch and power in those two minutes and got you more notice than perhaps a much better written monologue, but it didn’t have such immediate punch that you could get in 90 seconds or two minutes. So unfortunately it moved a tide toward more adult language and away from what was much better material without that.”

After a staffer in the lieutenant governor’s office attended a showcase some 15 or so years ago and voiced language and content concerns to Higgins, as did some letters he received, he said the state board of the Thespians moved to address the issue.

Higgins explained, “At the state level we were told that we could not edit these Miami-Dade kids at all or offer any roadblock to their performing because if we did, that county, which was the biggest participator of the state festival would pull out. Then we thought we needed a merger of these ideas here, how could we accommodate what at that time was a quite liberal south Florida from what’s always been a quite conservative north Florida, especially northwest Florida.

“We weren’t going to get into that game of saying one word’s bad or another situation’s bad. What we were going to do was create an asterisk, essentially putting the responsibility back on the artists, saying, ‘Artist, you want to do something that may offend some people for whatever reason. You have a responsibility before your piece to inform your audience that there is something that maybe some would consider objectionable, give a very brief synopsis of what that may be and then allow time for anybody who chooses not to be part of that to get up and leave the space before you do your material,’ putting the onus on the actual performer.

“We weren’t going to get into that game of saying one word’s bad or another situation’s bad. What we were going to do was create an asterisk, essentially putting the responsibility back on the artists, saying, ‘Artist, you want to do something that may offend some people for whatever reason. You have a responsibility before your piece to inform your audience that there is something that maybe some would consider objectionable, give a very brief synopsis of what that may be and then allow time for anybody who chooses not to be part of that to get up and leave the space before you do your material,’ putting the onus on the actual performer.

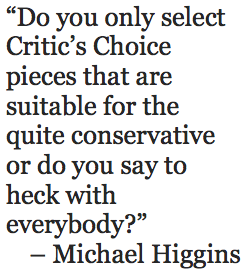

“That worked well for many, many years. It became a bit of an issue when at big events like closing ceremonies, Critic’s Choice when all the winners were showcased and we were doing these in big theatres, 1,000 seats theatres and then on practical terms when Susie got up to do her monologue and said before it, ‘it contains objectionable material’ that the audience was in no way going to be able to make a choice to leave or stay. So we had to address that concern now. Do you only select Critic’s Choice pieces that are suitable for the quite conservative or do you say to heck with everybody and allow every piece to go and just field the complaints of those who are troubled by it?

“The solution that was found at that time was that I as state director took the responsibility on myself as head honcho and I would watch all of the pieces and I would let the piece know ‘this does contain some objectionable material.’ Do you want to edit out these couple of words or option two, not perform it but still get your notice, awards, prizes and mentions at the festival? But now you as the artists have got to understand that you have an audience that is mixed in their liberal/conservativeness, they do not have the option to exercise their right to exit and not participate in theatre, so in order to preserve the festival there is something greater than your free choice at this adolescent age and you must work for the greater good. That worked for quite a while with some groups deciding I don’t want to be censored, so they didn’t perform yet won all of their awards and bells and whistles, and others saying, ‘oh sure, if it’s a matter of getting rid of the word fuck twice I can say that is not really a big deal to me and I understand that the audience has changed from what happened in a small room of 30 people to an audience now that has 10,000 people with young children and families and all kinds of people.’ The switch is for the audience, just like good old theatre.”

* * *

The Guirgis scene was suggested to Ferro and Roldan by one of their teachers, Elena Maria Garcia, an adjunct at New World School with 14 years experience.

“I love [Guirgis’s] work,” said Garcia, “and I said to the boys, ‘If there’s anybody in this class who will really understand this piece, and just be able to play it, not for the shouting or any of that stuff, because it’s really easy to do that, but for the compassion and the struggle – really what that scene is about between Judas and Jesus. I said you guys can pull this off.’ They struggled a lot but they finally got it and it was just glorious. It was just one of those moments that you go ‘Wow, this is why I teach. This is why I sit in traffic ever day.’ When you see moments like that you go, ‘Damn’.”

Annie McAdams, a faculty member at NWSA, was new to the school and the world of Thespian competition at the start of the current school year. Asked whether she had any initial concerns about the scene being in competition, given the language, she said, “I was not worried about the content of their scene. I wondered if the Thespians would like the content of their scene, and it occurred to me that it might be a hard piece to win a festival with because of the content. Not only that it had profanity but also the subject matter – that it’s Jesus and Judas arguing. I moved to Florida from New Jersey which is a blue state. Everyone feels that Florida is liberal, but I’ll tell you, it’s not as liberal as the northeast. So yes, it occurred to me that they might not win with it, but I knew that they could compete.”

When asked about their awareness of any guidelines about content or performance, both Garcia and McAdams cited the asterisk rule. McAdams said she didn’t know of more, while Garcia said she knew there were some for the state festival, but deferred to McAdams as the official head of the troupe.

Asked about this, Painter cited the following guidance on the Florida Thespian website:

The board wishes to restate its position that the sponsor and student should choose material that they would feel comfortable sharing in front of their peers and their school. The material chosen should match the community standards of your school district and your town! There should NEVER be an attempt to choose material for competition that you would “never be able to do on your own stage.” There is no shortage of prize-winning, world-class drama that would be acceptable in any high school in the state!

To this end, you will find the following statement in the registration for state. Both you, the sponsor, and the principal* or his/her designee are asked to sign the following:

The board requests that you verify that each piece which will be performed representing your school has been screened by the sponsor and endorsed by the principal or his/her designee. We ask you to certify that each piece meets your community standards and the standards set by your school and your school board. We also understand this caveat will not guarantee that all material presented will fit the guidelines of all schools. To that end, we will continue to use the asterisk as a further means of denoting material which might be considered sensitive for some viewers.

*NOTE: In Dade County the teacher, not the principal will be asked to certify that the piece meets community standards.

Set off separately, the statement continues:

Florida State Thespians does not pre-approve the material which is presented at this conference. The individual director is the ultimate judge of what is suitable for his/her students to perform for their home school audience. They are also responsible for placing the asterisk on any of their entries which might be questionable in nature. All material performed at this conference has been approved by the principal of the originating school. That approval indicates that he/she attests that the pieces submitted from that school would be suitable for general audience presentation at the school from which it came.

Even with these warnings and precautions, we realize that some of the more mature material may trouble some of our audience. We have endeavored to forewarn by the use of the asterisk and, at the Closing Ceremony, by identifying edgy material prior to its presentation. Should any member of our audience be offended by any performance, we encourage them to voice their concern to the State Director who has been directed by the State Thespian Board to forward those letters of complaint to the administrator involved. The administrator who approved the material in the first place is the person who should be able to defend his/her choice.

We cherish the right to free expression, but we also understand that, as educators, we have a responsibility to use that freedom wisely. We have tried to differentiate between words which might offend and ideas which might make the audience uncomfortable. Theatre, at its highest, may create dissension and make people examine their beliefs. Blasphemy and blatant sexual references are not suited to this conference. We have encouraged everyone to be sensitive to them starting at the district level. Discussion of contemporary issues and problems are the stuff of real theatre and deserve a place on our stages. Community standards differ widely in our state and this is a thorny issue we do not take lightly. As theatre educators, we cannot solve the problems of society by refusing to give a platform where those problems can be examined in an intelligent and forthright manner. We feel giving audience members the opportunity to challenge some of the choices local administrators make will give a greater voice to everyone in our large and extremely diversified audience.

Julie Cohen Woffington, executive director of the Educational Theatre Association said that there are no such restrictions on the national festival. As for guidelines for each state group, she wrote, “We have suggested guidelines for the individual events program that are available online, but they do not refer to choice of material or language.” Asked about any policy regarding the alteration of texts for competition or performance at the national festival, Woffington replied, “We have a statement on Freedom of Expression on our website. We also have information in the individual events guidelines that require securing performance rights.”

* * *

Returning to the night of the showcase, Roldan describes his reaction at the Sophie’s Choice he and Ferro had been given: remove the language or forego performing.

Returning to the night of the showcase, Roldan describes his reaction at the Sophie’s Choice he and Ferro had been given: remove the language or forego performing.

“At that moment, I was kind of disappointed,” Roldan said. “I was pretty sad. It was heartbreaking to hear that we would have to clean it up or not perform. The thing is, we always thought that the words were put in there for a purpose and they do have a meaning in the piece. So you might be able to change a few but even if you do the piece might lose some of its importance and some of its value.”

Asked if they had given any thought to changing the piece, Ferro said, “I was considering it. Tomas was calling Garcia – we were both shocked a little bit. So he called Garcia and I was thinking maybe we should change it. I just wanted to perform it. It was Tomas, who after he hung up with Garcia, who turned to me and said I guess we can’t perform it. He had already kind of made the decision. That’s how me and Tomas work, we kind of take turns making big things like that and I agreed with him completely. I don’t even know what I was thinking. You’re right, we shouldn’t perform it.”

McAdams recalls asking the students, “Are you sure you don’t want to just change the language? So that you can perform? I knew they were so proud, and I knew they had worked so hard, and honestly I didn’t think they had a chance of winning really because of Jesus and Judas, more than the profanity. So I really wanted them to have that experience of performing in front of their peers on that big stage. They said absolutely not.”

With McAdams’s help, Roldan and Ferro crafted a brief statement, which they read from the stage during the Showcase instead of performing their scene. It said:

Today we will not be performing a duet scene from The Last Days of Judas Iscariot by Stephen Adly Guirgis. We were thrilled to be awarded the Critic’s Choice for our category. We chose a scene we love by an artist we respect. The scene is asterisked for language and content. Tonight Florida State Thespians is asking us to alter our scene by removing the offensive language. We feel as young artists that this language is an integral part of the author’s intention in the scene. Rather than censor our scene, we have chosen to perform our piece outside. In 15 minutes we will be outside by the steps to perform. Please join us to support Art.”

* * *

I’d like to make some observations about what transpired in Florida two weeks ago.

It is clear that the state organization does have guidelines for performances at the showcase which differ from the guidelines that apply to competing works. It is certainly unfortunate that Garcia and McAdams were either unaware or not fully aware of them. While Lindsay Painter admitted to me that, “I don’t think it’s terribly easy to find and obviously after this conversation and this issue this year, we will make sure that’s easier to locate,” the way events unfolded for Roldan and Ferro might have been anticipated had they seen that language or been advised of it. That said, it’s worth noting that according to the young men, at no point in the adjudication process, either at their district level (where they did not receive an award and so were not eligible to perform) or the state level did anyone affiliated with the competitions make Roldan and Ferro aware of the potential restrictions on their performance until after they’d won and were at the final screening.

But perhaps it’s a good thing that things fell this way, because it reveals the strain of censorship that does affect the public performances at the Festival. Deploying language about “blasphemy and blatant sexual references” in performance, it is clear that the Florida festival is exercising judgment over what is permissible and what isn’t, and doing so rather late in the game to boot. There is no way of deciding definitively what is or is not blasphemy or blatant sexuality, even if you’re willing to grant that such a restriction is appropriate; it’s always going to be a judgement call. It’s worth noting that while a synonym for “blasphemy” is “obscenity,” “blasphemy” in its primary usage refers to “impiety” and in some cases irreverent behavior towards anything held sacred, not simple cursing. In the scene from Guirgis’s play, the word “fuck” or “fucking” is used as an interjection or adjective; at no time does it refer to a sexual act.

But perhaps it’s a good thing that things fell this way, because it reveals the strain of censorship that does affect the public performances at the Festival. Deploying language about “blasphemy and blatant sexual references” in performance, it is clear that the Florida festival is exercising judgment over what is permissible and what isn’t, and doing so rather late in the game to boot. There is no way of deciding definitively what is or is not blasphemy or blatant sexuality, even if you’re willing to grant that such a restriction is appropriate; it’s always going to be a judgement call. It’s worth noting that while a synonym for “blasphemy” is “obscenity,” “blasphemy” in its primary usage refers to “impiety” and in some cases irreverent behavior towards anything held sacred, not simple cursing. In the scene from Guirgis’s play, the word “fuck” or “fucking” is used as an interjection or adjective; at no time does it refer to a sexual act.

If in fact scenes that aren’t “appropriate” for the final showcase are being scored poorly to avoid the sort of conflict that arose over the scene from Judas Iscariot, that’s a black mark on the entire adjudication process. Not only did McAdams say that she had been told this was the case, but let’s also recall Painter’s slightly ambiguous, halting, “This piece was probably, had I known ahead of time, that the judges did not give us an alternate, I probably would have suggested it not even necessarily be – just to save them the heartache of having to go through that moment.” That can be construed to corroborate what McAdams heard about judging, although it stops short of being explicit. [Updated: please see addendum below with Lindsay Painter’s clarification of position on the issue of instructions and process for adjudication.]

I should note that late in our conversation, Painter introduced the idea that the reason Ferro and Roldan were not permitted to perform was because of how they behaved when given their choice, suggesting they had “started harassing other troupes and other humans.” I suspect that teenagers hearing such news for the first time may well have acted out in some way, though Ferro denied it and McAdams said she saw no such behavior and was told of no such behavior when she arrived backstage. I was surprised when Painter raised it 22 minutes into a 29 minute conversation; if it was central to the decision, it seems it should have been brought up as a factor much sooner.

Because of the Festival’s policy of placing the responsibility for the scenes chosen on school officials, with Miami-Dade having a different policy than the other districts, there has always been the potential for crossing some invisible line as Ferro and Roldan did. But by actively urging them to alter the author’s language, the festival applies censorship pressure as a prerequisite for performing some winning “asterisked” work, and based on the accounts from both Painter and Higgins, this is common practice. That is a poor example to set for students, teachers or parents – the work of authors cannot and should not be altered to meet the perceived need of an audience. That the festival has codified such actions in order to defend the festival against those who would dictate content to all is troubling, to say the least.

I will acknowledge that the State Festival organizers have challenges, not least the huge scale and popularity of their successful event. More importantly, they grapple with the reality that few states or even individual towns have unanimity about what is blasphemous, blatantly sexual, or obscene, and they’re trying to maintain an event statewide. But I think it’s fair to say that even the most liberal school has a sense of what is appropriate for their students, and by leaving the content, and quite explicitly any blame for that content, to the schools, the Florida festival must find a better solution to its current practice of altering content and staging to suit a homogeneous audience in an effort to minimize complaints. Perhaps “asterisked” scenes should be adjudicated together and have a defined portion of the showcase evening, while the self-identified inoffensive material is gathered separately at all stages. In that way, students whose schools permit them more latitude will be assured of both fair judging and the opportunity to perform. But altering a playwright’s words violates copyright law, and doing so in order to placate sensibilities remains censorship, no matter how it is rationalized.

I have written before that I believe that school theatre is first and foremost for the students – not for their parents, their siblings or the general public. Students should have the opportunity to take on challenging work, contemporary as well as classic work. If that work contains “strong” language but is within the education parameters of their school, so be it. “Protecting” the students, or an audience, from words or ideas should not drive education or school-related activities.

* * *

Ferro and Roldan both cite the idea of performing their scene outside as having come from one of the same adjudicators who gave them the “censor or don’t perform” ultimatum, saying he seemed genuinely sympathetic to the decision they faced. I asked them both how the impromptu performance went.

Ferro and Roldan both cite the idea of performing their scene outside as having come from one of the same adjudicators who gave them the “censor or don’t perform” ultimatum, saying he seemed genuinely sympathetic to the decision they faced. I asked them both how the impromptu performance went.

Roldan said, “Well at that point we were all adrenaline, I would say, especially Matthew. He really got on board and once he got on board he was completely on the bull and he was just going at it. We just performed it, a whole lot of people came and it was a great experience. The scene itself, I felt that while we did it outside, it wasn’t the best we did it, because at that point we were doing it now out of frustration and we had all those emotions inside of us, so I felt that maybe made us deviate from the scene. It still came out great, but not as good as it came out when we showed the piece for the first time in the competition.”

Ferro also felt the scene lost something. “I gotta be honest, it wasn’t the same,” he said. “For myself, I wish it hadn’t gone down that way because I feel like the whole point was kind of lost, the whole point of just doing the scene, the beautiful scene, was lost. I wouldn’t say it was because of Tomas. I kind of blame myself because I was so amped up on trying to get the crowd to listen to me and I was very energetic, I don’t think I was able to calm down and perform the piece like we’d rehearsed a thousand times. I don’t know. For me, it’s sad that the piece wasn’t as good as we had done it a million times before.”

Garcia viewed it very differently. “I’m thinking, OK, because there’s a massive dance where these teens go to right afterwards to celebrate the end, I said to them, I think you might get a few [people to watch]. I don’t think you’ll get that many kids because they’ll want to go to the dance. How wrong was I? There were over 200 kids standing on the lawn in their beautiful gowns and high heels going into the soil. They didn’t care, they were all there in silence watching these boys do their piece. It was right out of a movie. I was like, I can’t believe, they will never forget this. This is such a wonderful moment right now. I just thought Guirgis would be, ‘My god, they’re still hearing my work.’ These kids are anti-censorship and they kept hugging the boys and saying, ‘Thank you so much for doing the right thing. This is what its about – we’re artists and we shouldn’t have to change our work.’ It was beautiful.”

Though the young men refused their achievement prizes that night, McAdams brought them home, suspecting they’d ultimately want them, and both Ferro and Roldan expressed regret that they hadn’t ultimately accepted the recognition that evening, that they hadn’t respected the Festival more even at a moment of crisis.

Though the young men refused their achievement prizes that night, McAdams brought them home, suspecting they’d ultimately want them, and both Ferro and Roldan expressed regret that they hadn’t ultimately accepted the recognition that evening, that they hadn’t respected the Festival more even at a moment of crisis.

When asked whether she might recommend different material for students in the future as a result of what transpired, McAdams said, “I guess there would be a discussion I would have with the kids: ‘Look, if you want to win, here are the parameters you need to be in.’ But as a teacher, I would say, ‘Pick material you respond to, pick material that you are passionate about. Pick writing that’s good’.”

Ferro, asked if he had known all that was going to happen, would he have chosen a different scene, said simply, “No, I really wouldn’t have.”

I’m pleased that Ferro and Roldan are juniors, not only because they will have the opportunity to compete and perhaps win one more time (Garcia says she’s pointed them towards True West) but because it gives the Florida Thespian Festival the opportunity to right a wrong – and I believe it is a wrong, regardless of the forewarning on their website. Roldan and Ferro should be given the opportunity to perform their scene from The Last Days of Judas Iscariot on the main festival stage next year, all “fucks” intact.

And, of course, they still have a shot at the National Festival in June. I’m rooting for them.

* * *

Addendum, April 15, 3:50 pm: Upon reading this post, Lindsay Painter asked me to include the following information regarding the adjudication process.

The judges are not encouraged or told to be concerned about the asterisks when providing a score and feedback. In fact, when I meet with them each morning of the festival, it is one of my main points I make. The students of Florida should be receiving honest non-bias feedback from the professionals we hire to adjudicate. To suggest otherwise, in regards to how our organization has been handling the showcase is faulty. The judges have nothing to do with the showcase. They give us their picks for who the best in the room was, (all regards to content aside) and that makes-up the list for showcase. But, they have nothing to do with our asterisks system or the system we’ve had in place for preparing the showcase presentations.

Painter further requested that the following distinction be made, and because I write in the interest of constructive dialogue on these issues, I share it as well:

This is a Theatre Festival, not a competition. There is no prize, no winner. Each performance is provided an assessment. We showcase one piece from each room as a way to celebrate the work the students of Florida have brought to the festival. It’s not a thing to win or not win. And if they are not able to perform, an alternate does. This is the spirit of the festival. There is no placing or winning of the Florida State Thespian Festival. Only of presenting, receiving valuable feedback, and celebrating the work of the student artists. These students were not impacted in any way in the feedback or rating they received by the judges. They were given their superior. That is the highest honor they, or any student at the festival, can hope to achieve.

Correction, April 15 3:45 pm: This post originally stated that Michael Higgins was Lindsay Painter’s direct predecessor. That was incorrect, and is now accurately reflected above.

Correction, April 16, 11:30 pm: This post has been corrected to reflect that New World School of the Arts is affiliated with the University of Florida, not Florida State University, as previously stated.

Full disclosure: I delivered a keynote and conducted a workshop on the subject of school theatre censorship last summer at the Educational Theatre Association’s annual teacher’s conference. EdTA paid me an honorarium and provided me with round-trip travel to Cincinnati and accommodations while there.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School for the Arts.