September 28th, 2017 § § permalink

This summer, when an attorney for actor James Franco sent New York’s People’s Improv Theatre a cease and desist letter regarding the venue’s planned presentation of the play James Franco and Me, PIT’s response was to cancel the booking. At the time, Kevin Broccoli, author and performer of JF and Me had no legal representation, and so the stories that emerged were that Franco had successfully shut down the production, as highlighted in numerous media outlets, including The New York Times and Rolling Stone.

Among the organizations that stepped in to assist Broccoli were the Arts Integrity Initiative and the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, and in August, DLDF secured the pro bono services of the law firm Davis Wright Tremaine to represent Broccoli in an effort to insure his play could be seen. Yesterday, DWT responded in writing to Thomas Collier, the attorney at Sloane, Offer, Weber and Stern, who had sent the original cease and desist, asserting that it was without foundation and that Broccoli may present the play and companies may produce it under the protections offered by the First Amendment.

In a statement to Arts Integrity, Broccoli said, “I’m truly amazed at the amount of support my play has received since July when this story broke. I’m very grateful to Davis Wright Tremaine, especially Nicolas Jampol and Kathleen Cullinan, who have been working tirelessly, and to Dramatists Legal Defense, who helped connect me with them. Right now it appears that there’s an opportunity to do the play at several theaters across the county, including New York, and that’s really been my goal from the beginning.”

Jampol’s letter to Collier asks for a response within two weeks. The full text, with all legal citations and footnotes, appears below. It makes for fascinating reading and important information for playwrights.

* * *

We represent playwright Kevin Broccoli in connection with your client James Franco’s attempt to pressure theatrical venues into cancelling performances of Mr. Broccoli’s play James Franco and Me (the “Play”). In particular, we write in response to your July 7, 2017 cease-and- desist letter to the People’s Improv Theater, which resulted in the cancellation of several performances of the Play.

For the reasons explained below, we are confident that your client does not have any valid claim in connection with the Play. Contrary to the assertions in your letter, the First Amendment provides playwrights and other creators of expressive works – including both your client and Mr. Broccoli – with robust protection against the claims you threatened. Put simply, Mr. Broccoli does not need Mr. Franco’s permission to perform the Play, and will perform the Play as he desires. Mr. Broccoli also reserves the right to take legal action if your client continues to interfere with his contractual relationships with theatrical venues.

The Play

In the Play, a character named Kevin – which is based upon, and typically played by, Mr. Broccoli – sits in a hospital waiting room while his father is dying. The “James Franco” character stays with Kevin during the agony and tedium of awaiting a loved one’s fate in a lonely and impersonal waiting room. Their wide-ranging discussion tackles numerous topics like art, passion, sexual identity, and death, while engaging in a critical exploration of Mr. Franco’s films and television projects, including 127 Hours, Spring Breakers, Pineapple Express, Rise of the Planet of the Apes, General Hospital, Spiderman, Oz the Great and Powerful, and This Is the End, among others.

In addition to exploring Mr. Franco’s works, the Play parodies the public perception of Mr. Franco as a passionate, eccentric actor and artist who fully invests himself in his work. In one scene, for example, the “James Franco” character describes how he emotionally cut off his arm in preparation for his role as Aron Ralston in 127 Hours. In other scenes, the character vehemently disclaims any interest in money, highlighting Mr. Franco’s perception as someone who is not simply interested in pursuing projects for maximum financial gain – he believes in the art, and strives for something more than wealth creation.

Apart from examining Mr. Franco’s career and public perception, the Play also uses the “James Franco” character as a vehicle to explore Mr. Broccoli’s own feelings about life, death, his career, and his relationship with his father against the looming sense of mortality in the hospital waiting room. As one review explained, “this play becomes a kind of meta commentary on life, celebrity, loss, failure and friendship.”1

While not relevant to whether Mr. Franco could establish a valid claim against Mr. Broccoli in connection with the Play, the fact is that Mr. Broccoli is a long-time admirer of Mr. Franco and his work, and the portrayal is overwhelmingly positive. The Play specifically refers to Mr. Franco as “one of the most spontaneous and unique performers of his generation,” and explains that if Mr. Franco “stands for anything, it’s artistic simplicity.”

Mr. Franco Has No Viable Right-of-Publicity Claim

The First Amendment protects Mr. Broccoli from any right-of-publicity or misappropriation claim in connection with the “James Franco” character in the Play. Under well-established law, celebrities simply do not enjoy absolute control over the use of their name and likeness, particularly in an expressive context, such as a play.2 Mr. Franco has benefited from this principle in numerous of his works with characters that were based on, or inspired by, real people and events.

In Sarver v. Chartier, 813 F.3d 891, 896 (9th Cir. 2016), for example, an Army sergeant brought right-of-publicity claims against the producers of the film The Hurt Locker, which featured a fictional character that the plaintiff contended was based on him. In affirming the dismissal of the claims, the court explained that “The Hurt Locker is speech that is fully protected by the First Amendment, which safeguards the storytellers and artists who take the raw materials of life – including the stories of real individuals, ordinary or extraordinary – and transform them into art, be it articles, books, movies, or plays.” Id. at 905. Almost four decades earlier, in Guglielmi v. Spelling-Goldberg Productions, 25 Cal. 3d 860, 862 (1979), Rudolph Valentino’s nephew sued over a television movie titled Legend of Valentino: A Romantic Fiction, a fictionalized version of his uncle’s life. In rejecting the claim, Chief Justice Bird wrote for the majority of the court in a now-widely-cited concurrence3 explaining that the First Amendment protected the film against plaintiff’s cause of action for misappropriation of Valentino’s name and likeness:

Contemporary events, symbols and people are regularly used in fictional works. Fiction writers may be able to more persuasively, or more accurately, express themselves by weaving into the tale persons or events familiar to their readers. The choice is theirs. No author should be forced into creating mythological worlds or characters wholly divorced from reality. The right of publicity derived from public prominence does not confer a shield to ward off caricature, parody and satire. Rather, prominence invites creative comment. Surely, the range of free expression would be meaningfully reduced if prominent persons in the present and recent past were forbidden topics for the imaginations of authors of fiction. Id. at 869.4

Without these critical protections, content creators would be required to obtain approval from any real person – or such person’s estate – depicted in a television series, motion picture, or theatrical production, which would allow them to veto controversial or unflattering portrayals. This would place a significant restriction on the marketplace of ideas and would have prevented the production of acclaimed films such as Spotlight, The Social Network, and Selma. As mentioned above, Mr. Franco himself is no stranger to depicting real individuals, including in Milk, Lovelace, and Spring Breakers, among many others.

Mr. Broccoli uses the “James Franco” character to comment on Mr. Franco’s career and public perception, while using it as a vehicle to explore Mr. Broccoli’s feelings about his own life and work, among other topics. In other words, in addition to dealing with a matter in the public interest – Mr. Franco and his career – the Play uses the character to enable Mr. Broccoli to “more persuasively, or more accurately, express [himself].” Guglielmi, 24 Cal. 3d at 869. See also Comedy III Productions, 25 Cal. 4th at 397 (explaining that “because celebrities take on personal meanings to many individuals in the society, the creative appropriation of celebrity images can be an important avenue of individual expression”). As a result, the Play enjoys broad protection under the First Amendment and against any potential right-of-publicity claim that Mr. Franco might assert.5

Mr. Franco Has No Viable Trademark-Infringement Claim

The Lanham Act and state trademark law do not exist to imbue trademark owners and celebrities with the unrestricted power to prevent the unauthorized use of their marks or names in expressive works. Instead, trademark law is “is intended to protect the ability of consumers to distinguish among competing producers, not to prevent all unauthorized uses” of a mark. Utah Lighthouse Ministry v. Found. for Apologetic Info., 527 F.3d 1045, 1052 (10th Cir. 2008). Based on the Play, no reasonable viewer would be confused into thinking that Mr. Franco had sponsored or approved the Play – in fact, the Play makes clear that the “James Franco” character is a fictionalized version of Mr. Franco, and there is absolutely nothing in the Play that suggests or implies that Mr. Franco himself had any involvement in the Play. The implausibility of consumer confusion would bar any trademark-infringement claim here.

Even if Mr. Franco could somehow establish the elements of a Lanham Act claim, it would still fail because the Play is an expressive work entitled to full First Amendment protection. When a Lanham Act claim targets the unauthorized use of a mark in an expressive work, the traditional likelihood-of-confusion test does not apply because it “fails to account for the full weight of the public’s interest in free expression.” Mattel v. MCA Records, 296 F.3d 894, 900 (9th Cir. 2002). Instead, such claims must pass the Rogers test, which bars any Lanham Act claim arising from an expressive work unless the use of the mark “has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever, or, if it has some artistic relevance, unless the title explicitly misleads as to the source or the content of the work.” Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994, 999 (2d Cir. 1989). The Rogers test is highly protective of expression, and has since become the constitutional threshold for Lanham Act claims arising from the unauthorized use of marks within expressive works.6

The first prong of the Rogers test is satisfied if the alleged mark as any artistic relevance to the underlying work. See Rogers, 875 F.2d at 999. Courts have interpreted this requirement to mean that “the level of artistic relevance of the trademark or other identifying material to the work merely must be above zero.” Brown v. Electronic Arts, Inc., 724 F.3d 1235, 1243 (9th Cir. 2013) (brackets omitted). The second prong of the Rogers test is satisfied unless the defendant’s work makes an “overt claim” or “explicit indication” that the plaintiff endorsed or was directly involved with the work. Rogers, 875 F.2d at 1001 (“The title ‘Ginger and Fred’ contains no explicit indication that Rogers endorsed the film or had a role in producing it”). This requirement of an “overt claim” applies even where consumers mistakenly believe there is some connection between the mark owner and the expressive work. See, e.g., ETW, 332 F.3d at 937 n.19 (finding that a painting of Tiger Woods did not expressly mislead consumers despite survey evidence that sixty-two percent of respondents believed the golfer had “an affiliation or connection” with the painting “or that he has given his approval or has sponsored it”).7

Because the Play is an expressive work entitled to full First Amendment protection, the Rogers test would apply to any trademark claim Mr. Franco might bring. It is beyond dispute that Mr. Franco’s name is artistically relevant to a play that examines his career and public persona. Moreover, the Play does not make any explicit claim that Mr. Franco endorsed or was affiliated with the Play. To the contrary, Mr. Broccoli made clear in press interviews that the “James Franco” role would be played by different actors – not Mr. Franco8 – and never made any statement or suggestion that Mr. Franco sponsored or was otherwise involved with the Play. Accordingly, because the Rogers test is easily satisfied, the First Amendment bars any trademark-infringement claim by Mr. Franco.9

Mr. Franco Must Cease Interfering with the Exhibition of the Play

We request that Mr. Franco stop interfering with Mr. Broccoli’s right to exhibit the Play, and Mr. Broccoli expressly reserves his right to pursue a claim for such interference. Despite the fact that he can rightfully exhibit the Play without Mr. Franco’s permission, Mr. Broccoli is still an admirer of Mr. Franco, and is willing to engage in dialogue with him or his representatives regarding any specific objections he has to the Play or whether any particular disclaimer would alleviate Mr. Franco’s concerns. Like Mr. Franco, Mr. Broccoli is dedicated to his artistic craft, and despite his legal right to exhibit the Play without Mr. Franco’s permission, he would prefer to focus his time and energy on the Play, and not this dispute.

Footnotes

1 https://www.broadwayworld.com/rhode-island/article/BWW-Review-Unique-and- Hilarious-JAMES-FRANCO-AND-ME-At-Epic-Theatre-Company-20161121.

2 As one court explained in affirming the dismissal of a right-of-publicity claim arising from a film, “[t]he industry custom of obtaining ‘clearance’ establishes nothing, other than the unfortunate reality that many filmmakers may deem it wise to pay a small sum up front for a written consent to avoid later having to spend a small fortune to defend unmeritorious lawsuits such as this one.” Polydoros v. Twentieth Century Fox, 67 Cal. App. 4th 318, 326 (1997).

3 See Comedy III Productions v. Gary Saderup, 25 Cal. 4th 387, 396 n.7 (2001) (recognizing that Chief Justice Bird’s concurrence “commanded the support of the majority of the court”).

4 Chief Justice Bird also explained that it would be “illogical” if the First Amendment allowed the defendants to exhibit the film, but prohibit them from using Valentino’s name in advertising for the film. Id. at 873. See also Polydoros v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 67 Cal. App. 4th 318, 325 (1997) (holding that the use of the plaintiff’s name and likeness in a film was not an actionable violation of the right of publicity, and thus “the use of his identity in advertisements for the film is similarly not actionable”).

5 The transformative-use defense would provide another layer of constitutional protection against a right-of-publicity claim because Mr. Franco’s likeness is “one of the ‘raw materials’ from which an original work is synthesized,” and his “likeness is so transformed that it has become primarily the defendant’s own expression.” See Winter v. DC Comics, 30 Cal. 4th 881, 888 (2003).

6 See, e.g., Cliffs Notes v. Bantam Doubleday Dell, 886 F.2d 490, 495 (2d Cir. 1989) (holding that “the Rogers balancing approach is generally applicable to Lanham Act claims against works of artistic expression”); ETW Corp. v. Jireh Pub., Inc., 332 F.3d 915, 928 n.11 (6th Cir. 2003) (explaining that the Rogers test is “generally applicable to all cases involving literary or artistic works where the defendant has articulated a colorable claim that the use of a celebrity’s identity is protected by the First Amendment”); E.S.S. Entm’t 2000 v. Rock Star Videos, 547 F.3d 1095, 1099 (9th Cir. 2008) (“Although [the Rogers test] traditionally applies to uses of a trademark in the title of an artistic work, there is no principled reason why it ought not also apply to the use of a trademark in the body of the work.”); Univ. of Alabama v. New Life Art, 683 F.3d 1266, 1278 (11th Circ. 2012) (expressing “no hesitation in joining our sister courts by holding that we should construe the Lanham Act narrowly when deciding whether an artistically expressive work infringes a trademark,” and applying Rogers to “paintings, prints, and calendars”).

7 Similarly, the Rogers court found that the defendants did not expressly mislead despite evidence that “some members of the public would draw the incorrect inference that Rogers had some involvement with the film.” 875 F.2d at 1001. The court explained that any “risk of misunderstanding, not engendered by any overt claim in the title, is so outweighed by the interests in artistic expression as to preclude application of the Lanham Act.” Id.

8 http://www.providencejournal.com/news/20161107/theater-review-intriguing-james- franco-and-me-at-cranstons-epic-theatre.

9 Any unfair-competition claim would fail for the same reasons as a right-of-publicity or trademark-infringement claim. See, e.g., Kirby v. Sega of America, 144 Cal. App. 4th 47, 61-62 (2006) (where First Amendment barred plaintiff’s misappropriation and Lanham Act claims, it also barred her unfair-competition claim).

July 10th, 2017 § § permalink

This week, Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman’s 1990 musical Assassins will have its first major New York performances since the 2004 Roundabout Theatre Company production*, in a concert version as part of City Center Encores!’s Off-Center series. Given the controversy sparked last month by The Public Theater’s Julius Caesar, in which Caesar and his wife were portrayed as analogues of Donald and Melania Trump, prompting the withdrawal of sponsors, sparking disruptions of performances and precipitating threats against the production, the theatre, the artists and the staff, it seemed an appropriate moment to speak with Weidman about how Assassins has been perceived over the past 26 years and how the newest incarnation might be received. Weidman, a former president of The Dramatists Guild, currently serves as president of the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, founded to, according to the organization’s website, “advocate, educate and provide a new resource in defense of the First Amendment.” This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This week, Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman’s 1990 musical Assassins will have its first major New York performances since the 2004 Roundabout Theatre Company production*, in a concert version as part of City Center Encores!’s Off-Center series. Given the controversy sparked last month by The Public Theater’s Julius Caesar, in which Caesar and his wife were portrayed as analogues of Donald and Melania Trump, prompting the withdrawal of sponsors, sparking disruptions of performances and precipitating threats against the production, the theatre, the artists and the staff, it seemed an appropriate moment to speak with Weidman about how Assassins has been perceived over the past 26 years and how the newest incarnation might be received. Weidman, a former president of The Dramatists Guild, currently serves as president of the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, founded to, according to the organization’s website, “advocate, educate and provide a new resource in defense of the First Amendment.” This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Howard Sherman: Given the state of discourse about public expression, given what happened with Julius Caesar in Central Park, it seems that putting up this show at this moment carries not necessarily more weight than other times, but that people may bring some other baggage to it in a different way they might have at other times. Back in 1991, it did not move to Broadway, the reason given being it wasn’t the right time, it was the first Gulf War, etc. Then there was the first planned Roundabout production, coming right after 9/11, when you and Steve and others felt it was not the right time to do the show. So is there ever a right time or ever a wrong time to do Assassins?

Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman

John Weidman: I don’t think there’s ever a wrong time to do it. I think the reception of the first production was honestly more a function of the fact that people did not know what to expect when they came into to theater. They were not prepared for the shock value of the opening number, which was a deliberate choice on our part to kind of knock the audience off balance. I think that, 25 years ago, even though there had been many adventurous musicals that had been done, some people simply assumed that the musical theater was not an appropriate place in which to tackle material that was this fundamentally serious. I think we’re well past that assumption at this point, given the kind of musicals that have been written in the last 25 years.

When the show was scheduled to be done at the Roundabout, and when we decided to delay the production after 9/11, that wasn’t a good time to do Assassins. But it wasn’t because we thought people would find the show problematic, that they would resent a show about presidential assassins in that sudden new political moment. In order to engage an audience, given the way the show’s designed and the way it’s written, it requires an audience which is, frankly, prepared to laugh in certain places, to take the humor on board. That’s part of the roller coaster ride of the show. We all felt that at that time, it was unfair to ask an audience which was grieving to come into a theater and to engage this kind of material in a way that was intermittently humorous. The show in that context simply wouldn’t work. And If it wasn’t going to work, it made sense to delay the production.

As far as now goes? When the show first opened, we had a conservative Republican in the White House, and then for eight years we had a centrist Democrat in the White House, and then for eight years we had a conservative Republican in the White House, and then we had a centrist Democrat who was black, and now we’ve got this guy. The show’s been performed continuously over the course of those 25 years in all kinds of different political and socioeconomic contexts. This is just a different one.

That said, people will obviously come into the theater from a different place, because the world outside the theater is a different place. Which will affect the way in which the members of the audience take the show on board.

But I don’t think it makes it a particularly good or bad time to do Assassins. Personally, I think it’s always a good time to do the show, because the show is meant to be provocative, and hopefully people will walk out of the theater talking about it, that it will provoke the kinds of conversations that Steve and I hoped it would provoke when we wrote it. That should happen now the way it’s happened with previous productions. They may be different conversations, but that’s what I would hope would happen.

Sherman: Have you and Steve made any changes in the show since it was last seen in New York, since the 2004 Roundabout production?

Weidman: No. The text of the show that’s going to be performed at City Center is exactly the same as the text which was performed at the Roundabout. And the text at the Roundabout was exactly the same as the text that was performed at Playwrights Horizons with the exception of “Something Just Broke,” the song which we added in London. The show’s really been what it’s been since it was first performed 25 years ago.

The 2017 Yale Repertory Theatre production of “Assassins” (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Sherman: Assassins was performed this spring at Yale Rep. Was there a difference in response to the show than for previous productions?

Weidman: You know, I was curious to see if there would be a difference in the way in which the show was received after the last election, and Yale was the first significant production that was available to me. I didn’t feel, sitting in the audience, as if there was any kind of shift that I was aware of in terms of the way in which the audience was connecting to the material.

Sherman: Speaking to you both as an author of the piece, and also in your role with the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, it’s fair to say that there was some very heightened conversation, and actions around the Julius Caesar, admittedly by people who didn’t see it, didn’t take the time to understand it or understand its context. In the wake of that, are you concerned at all about how, not even the audience, but how people external to the audience might choose to speak about this piece?

Weidman: The word you used was concerned. I’m not in any way worried about it. At the same time, I’m sensitive to the possibility that in this current political climate, there will be people who will react to the idea of a musical about the people who tried to attack the President, that they will react to that in a way which is similar to the way in which some people reacted to the show in 1991, when they hadn’t seen it and weren’t going to see it. They simply knew what the show was about, and they had a problem with that. That happened then and that could conceivably happen now.

I do think that we’ve had 25 years in which this show’s been performed a lot everywhere, and so people have a better idea of what the show’s ambitions are and what its intentions are. I’ve got Google alerts set on my computer to Assassins, because I’m always curious to see how the show’s being received. The reviews tend to be really good, which is always nice, but the main thing is people writing about the show all over the country, in a variety of different kinds of publications, seem to understand what Steve and I were intending. That’s really reassuring. People get the show. They can like any show, they can like it a lot or not like it a lot. But they seem to understand what we were doing, and I assume that that will be the case this time around as well.

Sherman: In reading some of the press about the prior productions and some of the commentary, one of the ways in which the show is described is that it’s about, and I’m not quoting here, I’m paraphrasing, it’s about an America that causes people who feel they have no voice to take extreme actions. As we look at politics today, there are those who say that where we are is about people who felt they were disenfranchised from the political system, and that has brought us to the real polarization that we’re at now. Might that affect people’s perceptions?

Sherman: In reading some of the press about the prior productions and some of the commentary, one of the ways in which the show is described is that it’s about, and I’m not quoting here, I’m paraphrasing, it’s about an America that causes people who feel they have no voice to take extreme actions. As we look at politics today, there are those who say that where we are is about people who felt they were disenfranchised from the political system, and that has brought us to the real polarization that we’re at now. Might that affect people’s perceptions?

Weidman: As Steve and I started to talk about this material 25 years ago, I realized at a certain point very early on that what drew me to the material was an attempt to explain something to myself which I had not understood since I was 17 years old when Kennedy was shot. The Kennedy assassination was my first real experience of loss and it was devastating to me. Two of my friends and I got together and we went down to D.C. and stood on the sidewalk as the funeral cortege went by, and all the subsequent attempts to try make sense of what happened — conspiracy theories. Was it the Cubans, was it the CIA, the FBI? It all seemed like, on some level, a waste of time to me. The fundamental question was: how could so much grief and pain be caused by one angry little man in a t-shirt with a rifle in Texas?

When Steve and I started to talk about these other personalities who had articulated a variety of wildly different motives for attacking the President, we said, ‘Well if we gather them together and look at them as a group’ – something which had not been done much, even by academics – ‘would some common grievance, some common complaint beyond what they articulated begin to emerge? And if it did, that would be a useful thing to write about.’ That is at the heart of what the piece explores. The people who, with one or two exceptions, picked up guns did tend to be, when you look at them as a group, people who were operating on the margins, the fringes of what we would consider a mainstream American experience.

In the last election, a lot of people who you and I would have identified as operating on the margins of a mainstream middle-class American experience, cast their votes in a particular way and elected a particular guy President. That does seem to suggest a different way of looking at the characters on stage in the show. I’m not quite sure what the change is. I’m not quite sure what it means in terms of how one observes their behavior and listens to what they have to say. But we are in a different political moment, and that moment will undoubtedly have an impact on how the audience responds to the piece.

I do think it will probably make for conversations on the way out of the theater which will be different from the conversations people might have had five years ago or ten years ago. I’m not sure if any of that’s clear. If it’s not, it’s because it’s something I’m still working through in my own head.

The 2004 Roundabout Theatre Company production of “Assassins” (photo by Joan Marcus)

Sherman: Given that the run is sold out, if there is conversation about why this show at this time, and if people choose to try to politicize it, is there something you would like them to know beyond the simplistic plot descriptions of a marketing brochure or a PR release about the show?

Weidman: I have always felt that that it’s essential with this show that it be allowed to speak for itself. It obviously can only speak to the audience that’s in the building, but that’s true of any theater piece. You know, somebody can describe to you what Hamlet means, but if that’s all it took to appreciate Hamlet, then you wouldn’t have to waste time listening to Shakespeare’s language for three and a half hours. I think you need to experience the piece itself, and I think that’s true of this piece. That said, Assassins is an exploration of where these vicious acts came from, in an attempt to get a better handle on how to prevent them from happening again in the future.

Sherman: Speaking to your role with the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund: is there any sense that there has been a change in people wanting to assert their own prerogative over what happens on stage? Has that changed in the past six to eight months? Does DLDF have more concerns now than in the past, or is it just consistent with the kinds of challenges that you’ve faced?

Weidman: I’m not aware of any kind of seismic shift, in terms of what people are either attempting to repress or ways in which people are self-censoring, although it would be hard to know about the second one. It may be the decisions at the high school level, it may the decisions at the amateur level, but also at the stock level, that people are making more cautious decisions in terms of what they think a school board or parent body or a subscriber base is going to be comfortable with. It’s entirely possible that they are shying away from things which they think are likely to be controversial. I would obviously hope not, because this seems to me a period when it’s important for controversial material to be produced and to become part of the national conversation.

When DLDF gave an award last year to Jeffrey Seller, and Lin-Manuel Miranda, and Thomas Kail, and the cast of Hamilton for the speech that was made from the stage when Mike Pence was in the audience, I wrote the citation and I handed the award to Jeffrey. The point I wanted to make most forcefully was that Mike Pence apparently had stood there and listened and that was fine, but the President-elect the next morning had not only castigated the cast for being rude, but he had instructed them to apologize. I said if censors tell artists what they’re not allowed to say – here we have someone going beyond that, instructing artists what they’re required to say. The latter is a genuinely frightening prospect, and I wouldn’t have thought five years ago that it was something we had to be concerned about, but I think we all feel like we’re living in a new world where anything is possible and nothing is surprising.

* There was a one-night reunion concert of the 2012 cast, held as a benefit for Roundabout.

February 24th, 2015 § § permalink

Last night, I was extremely flattered and honored to receive the second annual Dramatists Legal Defense Fund’s “Defender” Award, for my work on behalf of artists’ rights and against censorship. My remarks were fairly brief (I know a little something about brevity and awards presentations, even when there isn’t an orchestra to “play you off”), so for those who have expressed interest, or may be interested, here’s what I had to say, following a terrific and humbling introduction by playwright J.T. Rogers, my newest friend.

Last night, I was extremely flattered and honored to receive the second annual Dramatists Legal Defense Fund’s “Defender” Award, for my work on behalf of artists’ rights and against censorship. My remarks were fairly brief (I know a little something about brevity and awards presentations, even when there isn’t an orchestra to “play you off”), so for those who have expressed interest, or may be interested, here’s what I had to say, following a terrific and humbling introduction by playwright J.T. Rogers, my newest friend.

I feel as if this evening is a classic Sesame Street segment, because as I see my name alongside those of such great talents as Annie Baker, Jeanine Tesori, Chisa Hutchinson, Charles Fuller and my longtime friend Pete Gurney, I can’t help feeling that one of these things is not like the others, one of these things doesn’t belong, namely me.

That said: I am honored more than you can possibly know to receive this recognition from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund and the Dramatists Guild, because I have spent the better part of my life in the dark with your stories, your characters, your words and your music, and my life is so much better for it.

My efforts on behalf of artists rights and against censorship began, four years ago, in what I merely thought was one blog post among many. My awareness and understanding has evolved significantly over that time. I am asked sometimes why I think there is so much more censorship of theatre now, and I’m quick to say that I know this has been happening for years, for decades; all I have done is, perhaps, to make some people more aware of some of the incidents, and to try to address them in greater depth than they might have otherwise received.

I think the same is true of unauthorized alteration of your work, sad to say. All I’ve been able to do is call more attention to it, in the hope of warning people off from trying it ever again. It is an uphill battle.

I want to thank John Weidman, Ralph Sevush and everyone who is part of creating the DLDF for giving me this honor, and to thank the Guild for being my partner and for welcoming me as your partner in these efforts. I want to thank Sharon Jensen and the staff and board of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts for allowing me the latitude to address these situations as they have arisen in the 18 months I have been part of that essential organization. I want to thank David van Zandt, Richard Kessler and especially Pippin Parker for making it possible for me to professionalize this work as the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama; I look forward to working with all of you through that new platform. And I especially want to thank my wife, Lauren Doll, for so many things, not least of which has been tolerating the late night and early morning calls with strangers around the country, often high school students, and the furious typing at all hours, whenever someone reaches out to me about censorship or the abrogation of authors rights.

I accept this award less for myself than for the students, teachers and parents who stand up for creative rights, in places like Maiden, North Carolina; South Williamsport, Pennsylvania; Plaistow, New Hampshire; Wichita, Kansas; and Trumbull, Connecticut, among others. If they didn’t sound the alarm, we might otherwise never know.

I should tell you that when I’ve visited some of these communities, I have had people come up to me repeatedly and tell me that I am brave for doing this work. ‘But I’m not brave,’ I tell them, ‘You’re the brave ones. I have nothing at stake here. You do.’

Indeed, I am not brave. What I am is loud. I will shout on behalf of theatre, on behalf of arts education, on behalf of creative challenge, on behalf of all of you here and all of those artists who aren’t here for as long I have a voice. And those of you who know me are fully aware that it’s very hard to shut me up.

My congratulations to tonight’s other honorees and thank you again for this award.

February 10th, 2015 § § permalink

Hannah Cabell and Anna Chlumsky in David Adjmi’s 3C at Rattlestick Playwrights Theater (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Seen any good productions of David Adjmi’s play 3C lately?

Sorry, that’s a trick question with a self-evident answer: of course you haven’t. That’s because in the two and a half years since it premiered at New York’s Rattlestick Playwrights Theater, no one has seen a production of 3C because no one is allowed to produce it, or publish it. Why, you ask? Because a company called DLT Entertainment doesn’t want you to.

3C is an alternate universe look at the 1970s sitcom Three’s Company, one of the prime examples of “jiggle television” from that era, which ran for years based off of the premise that in order to share an apartment with two unmarried women, an unmarried man had to pretend he was gay, to meet with the approval of the landlord. It was a huge hit in its day, and while it was the focus of criticism for its sexual liberality (and constant double entendres), it was viewed as lightweight entertainment with little on its mind but farce and sex (within network constraints), sex that never seemed to actually happen.

Looking at it with today’s eyes, it is a retrograde embarrassment, saved only, perhaps, by the charm and comedy chops of the late John Ritter. The constant jokes about Ritter’s sexual façade, the sexless marriage of the leering landlord and his wife, the macho posturings of the swinging single men, the airheadedness of the women – all have little place in our (hopefully) more enlightened society and the series has pretty much faded from view, save for the occasional resurrection in the wee hours of Nick at Night.

In 3C, Adjmi used the hopelessly out of date sitcom as the template for a despairing look at what life in Apartment 3C might have been had Ritter’s character actually been gay, had the landlord been genuinely predatory and so on. It did what many good parodies do: take a known work and turn it on its ear, making comment not simply on the work itself, but the period and attitudes in which it was first seen.

Enter DLT, which holds the rights to Three’s Company. They sent a cease and desist letter to Adjmi back in 2012 claiming that the show violated their copyright; Adjmi said he couldn’t afford to fight it. Numerous well-known playwrights wrote a letter in support of Adjmi and the controversy generated its first wave of press, including pieces in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Over time, there have been assorted legal filings by both parties, with another wave of press appearing last year just about this time, when Adjmi sued for the right to reclaim his play for production, with commensurate press coverage once again from the Times and Studio 360, among others.

Enter DLT, which holds the rights to Three’s Company. They sent a cease and desist letter to Adjmi back in 2012 claiming that the show violated their copyright; Adjmi said he couldn’t afford to fight it. Numerous well-known playwrights wrote a letter in support of Adjmi and the controversy generated its first wave of press, including pieces in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Over time, there have been assorted legal filings by both parties, with another wave of press appearing last year just about this time, when Adjmi sued for the right to reclaim his play for production, with commensurate press coverage once again from the Times and Studio 360, among others.

Why do I dredge this all up now? Because the bottom line is that DLT is doing its level best to prevent a playwright from earning a living, and throwing everything they can into a specious argument to do so. They say, both in public comments and in their filings, that 3C might confuse audiences and reduce or eliminate the market for their own stage version (citing one they commissioned and one for which they granted permission to James Franco). They cite negative reviews of 3C as damaging to their property. And so on.

But while I’m no lawyer (though I’ve read all of the pertinent briefs on the subject), I can make perfect sense out of the following language from the U.S. Copyright Office, regarding Fair Use exception to copyright (boldface added for emphasis):

The 1961 Report of the Register of Copyrights on the General Revision of the U.S. Copyright Law cites examples of activities that courts have regarded as fair use: “quotation of excerpts in a review or criticism for purposes of illustration or comment; quotation of short passages in a scholarly or technical work, for illustration or clarification of the author’s observations; use in a parody of some of the content of the work parodied; summary of an address or article, with brief quotations, in a news report; reproduction by a library of a portion of a work to replace part of a damaged copy; reproduction by a teacher or student of a small part of a work to illustrate a lesson; reproduction of a work in legislative or judicial proceedings or reports; incidental and fortuitous reproduction, in a newsreel or broadcast, of a work located in the scene of an event being reported.”

As someone who has gone out on a limb at times defending copyright and author’s rights, I’d be the first person to cry foul if I thought DLT had the slightest case here. But 3C (which I’ve read, as it’s part of the legal filings on the case) is so obviously a parody that DLT’s actions seem to be preposterously obstructionist, designed not to protect their property from confusion, but to shield it from the inevitable criticisms that any straightforward presentation of the material would now surely generate.

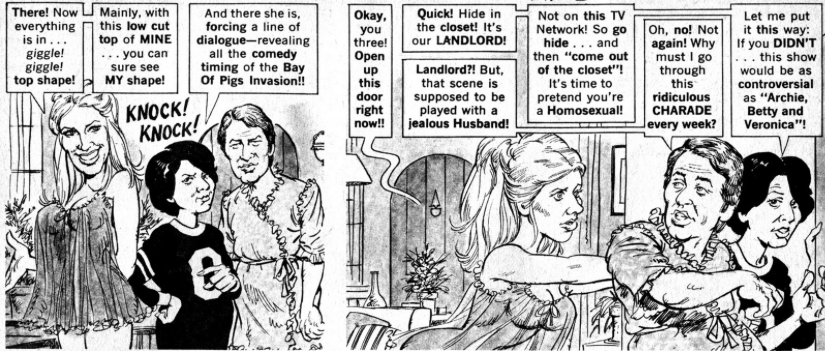

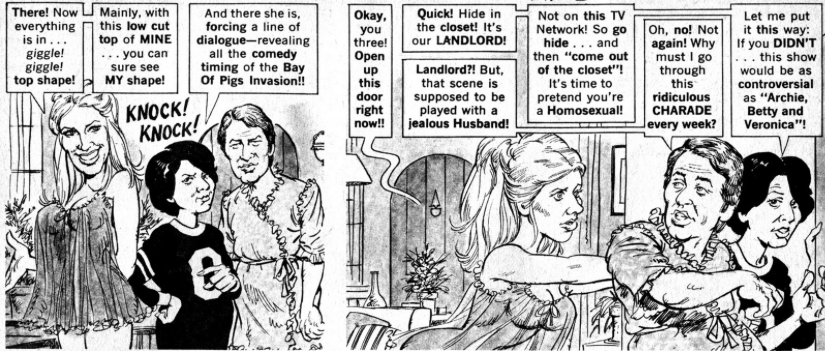

Rather than just blather on about the motivations of DLT in preventing Adjmi from having his play produced and published, let me demonstrate that their argument is specious. To do so, I offer the following exhibit from Mad Magazine:

What’s fascinating here is that Mad, a formative influence for countless youths in the 60s and 70s especially, parodied Three’s Company while it was still on the air, seemed to already be aware of the show’s obviously puerile humor, was read in those days by millions of kids – and wasn’t sued for doing so. That was and is a major feature of Mad, deflating everything that comes around in pop culture through parody. The fact is, Adjmi’s script is far more pointed and insightful than any episode of Three’s Company and may well work without deep knowledge of the original show, just like the Mad version.

The most recent filing in the Adjmi-DLT situation comes from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, an offshoot of The Dramatists Guild. Like all of the filings in this case, it’s very informative about copyright in general and parody in particular, and it spells out the numerous precedents where the use of a prior work was permitted under fair use, with particular attention to the idea that when the new work is transformative – which 3C surely is – it is permitted (read the complete amicus curiae brief here). In addition to their many examples, I would add from my own misspent youth such works as Bored of the Rings, a 1969 book-length parody of Tolkien by some of the people who would go on to create the National Lampoon, where incidentally, DLDF president John Weidman exercised his own comic skills) and Airplane!, which took its plotline (and punctuation mark) of a poisoned airline crew directly, uncredited, from the 1957 film Zero Hour! More recently, the endlessly touring Potted Potter has successfully run without authorization, though clearly derived from the works of J.K. Rowling and prior to any authorized stage interpretation.

The most recent filing in the Adjmi-DLT situation comes from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, an offshoot of The Dramatists Guild. Like all of the filings in this case, it’s very informative about copyright in general and parody in particular, and it spells out the numerous precedents where the use of a prior work was permitted under fair use, with particular attention to the idea that when the new work is transformative – which 3C surely is – it is permitted (read the complete amicus curiae brief here). In addition to their many examples, I would add from my own misspent youth such works as Bored of the Rings, a 1969 book-length parody of Tolkien by some of the people who would go on to create the National Lampoon, where incidentally, DLDF president John Weidman exercised his own comic skills) and Airplane!, which took its plotline (and punctuation mark) of a poisoned airline crew directly, uncredited, from the 1957 film Zero Hour! More recently, the endlessly touring Potted Potter has successfully run without authorization, though clearly derived from the works of J.K. Rowling and prior to any authorized stage interpretation.

It’s been months since there have been filings for summary judgment in the case (August 2014, to be precise), and according to Bruce Johnson, the attorney at Davis Wright Tremaine in Seattle who is leading the fight on Adjmi’s behalf, there is no precise date by which there will be a ruling. Some might say that I’m essentially rehashing old news here, but I think it’s important that the case remains prominent in people’s minds, because it demonstrates the means by which a corporation is twisting a provision of copyright law to prevent an artist from having his work seen – and that’s censorship with a veneer of respectability conferred by legal filings under the umbrella of commerce. There may be others out there facing this situation, or contemplating work along the same lines, and this case may be suppressing their work or, depending upon the ultimate decision, putting them at risk as well.

We don’t all get to vote on this, unfortunately. But even armchair lawyers like me can see through DLT’s strategy. I just hope that the judge considering this case used to read humor magazines in his youth, which should provide plenty of precedent above and beyond what’s in the filings. 3C may take a comedy and make it bleak, but there’s humor to be found in DLT’s protestations, which are (IMHO) a joke.

P.S. I don’t hold the copyright to any of the images on this page. I’m reproducing them under Fair Use. Just FYI.

February 13th, 2014 § § permalink

I’m not given to posting press releases here and this isn’t the start of a trend, but I’m making an exception to insure this good news gets around. There’s nothing for me to say beyond what this press release from The Dramatists Guild already says so well.

* * *

First Annual “DLDF Defender Award” Goes to Connecticut High School Student

The Dramatists Legal Defense Fund will present the first ever “DLDF Defender Award” to Larissa Mark, a high school senior from Trumbull, CT who successfully organized her community in opposition to her school’s sudden cancellation of their upcoming production of Rent, ultimately forcing the production’s reinstatement. This new award from the DLDF honors Ms. Mark’s work in support of free expression in the dramatic arts.

——————————————-

On February 24, 2014, the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc. will hold its annual Awards Night at the Lamb’s Club in New York City and among the other honors given that night, an award from the recently created Dramatists Legal Defense Fund will be presented to Trumbull high school student Larissa Mark. This first “DLDF Defender Award” honors Ms. Mark’s work in support of free expression in the dramatic arts.

On February 24, 2014, the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc. will hold its annual Awards Night at the Lamb’s Club in New York City and among the other honors given that night, an award from the recently created Dramatists Legal Defense Fund will be presented to Trumbull high school student Larissa Mark. This first “DLDF Defender Award” honors Ms. Mark’s work in support of free expression in the dramatic arts.

Larissa Mark is the current president of Trumbull High School’s Thespian Society, which had planned to stage Jonathan Larson’s musical “Rent” in March, 2014. However, Principal Marc Guarino put the production on “indefinite hold” in November due to the musical’s content, which he viewed as too controversial despite the fact that the students were going to present the show’s “school edition”. This version of the show was created for high school audiences (edited with the approval of the Larson estate) and has been produced for years all around the country without incident, including in neighboring Connecticut towns like Greenwich, Woodbridge, and Fairfield.

The cancellation inspired a “Rentbellion” amongst the Trumbull student body, expressed within the school’s halls and on social media. However, the president of the Thespian Society, Larissa Mark, took a different tact. She started petitions, put up a website, spoke to the media, and focused community resistance in a remarkably effective way. The story of Trumbull’s cancellation of “Rent” eventually attained national press, via The Washington Post and NPR’s Weekend Edition, among others.

At this point, the Dramatists Guild got involved. At the behest of the DLDF and Guild president Stephen Schwartz, and with the advice of the National Coalition Against Censorship, the Guild’s executive director of business affairs, Ralph Sevush, wrote directly to Principal Guarino to offer the Guild’s resources to assist in preparing Trumbull for the show’s subject matter with the kind of public discussions and events that the Principal had stated were necessary in order to reschedule the show. Receiving no response from the school, the Guild copied the letter to Trumbull parents, the school superintendent, the media, and to Ms. Mark.

Soon thereafter, the school eventually agreed to reinstate the production on its original March schedule (with no community events scheduled to date). And because playwrights everywhere had a vested interest in Ms. Mark’s campaign to ensure that the production of “Rent” went forward at Trumbull High School, the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund wished to honor her contribution to free expression in the dramatic arts with its first annual “DLDF Defender Award.”

Soon thereafter, the school eventually agreed to reinstate the production on its original March schedule (with no community events scheduled to date). And because playwrights everywhere had a vested interest in Ms. Mark’s campaign to ensure that the production of “Rent” went forward at Trumbull High School, the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund wished to honor her contribution to free expression in the dramatic arts with its first annual “DLDF Defender Award.”

According to DLDF president John Weidman (librettist of Assassins, Pacific Overtures, and Contact): “When a provocative piece of theater is cancelled anywhere, it has a chilling effect on the production of provocative theater pieces everywhere. In this instance, it was Larissa Mark’s effort, commitment, and leadership that ensured Jonathan Larson’s right to be heard.”

After being notified of the award, Ms. Mark said in response:

“Thank you so much for this tremendous honor… I would be incredibly remiss not to mention how much The Guild’s letter struck Mr. Guarino and aided our cause. The day after he received it I had a meeting with him where he mentioned the letter, and how much it affected him. Our entire community is so glad that we will be moving forward with the show, because theater is a place we are allowed to talk about “taboo” topics and express ourselves. Jonathan Larson and so many other playwrights have created marvelous pieces to tackle issues society faces, and the Thespians at Trumbull High felt it was very important to bring Larson’s work to Trumbull. I am so thankful towards everyone who helped work to bring back this show to our school. I am so thankful towards The Guild for this honor, and humbled by being recognized from such a prestigious group.”

The Dramatists Guild of America was established a century ago and is the professional trade association for playwrights, composers, lyricists, and librettists writing for the stage. The Guild has over 7,100 members nationwide and around the world, from beginning writers to the most prominent authors represented on Broadway. The current officers of the Guild are Stephen Schwartz (president), Doug Wright (vice-president), Peter Parnell (secretary), and Theresa Rebeck (treasurer).

The Dramatists Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization created by the Guild to advocate for free expression in the dramatic arts and a vibrant public domain for all, and to educate the public about the industry standards surrounding theatrical production and about the protections afforded dramatists under copyright law.