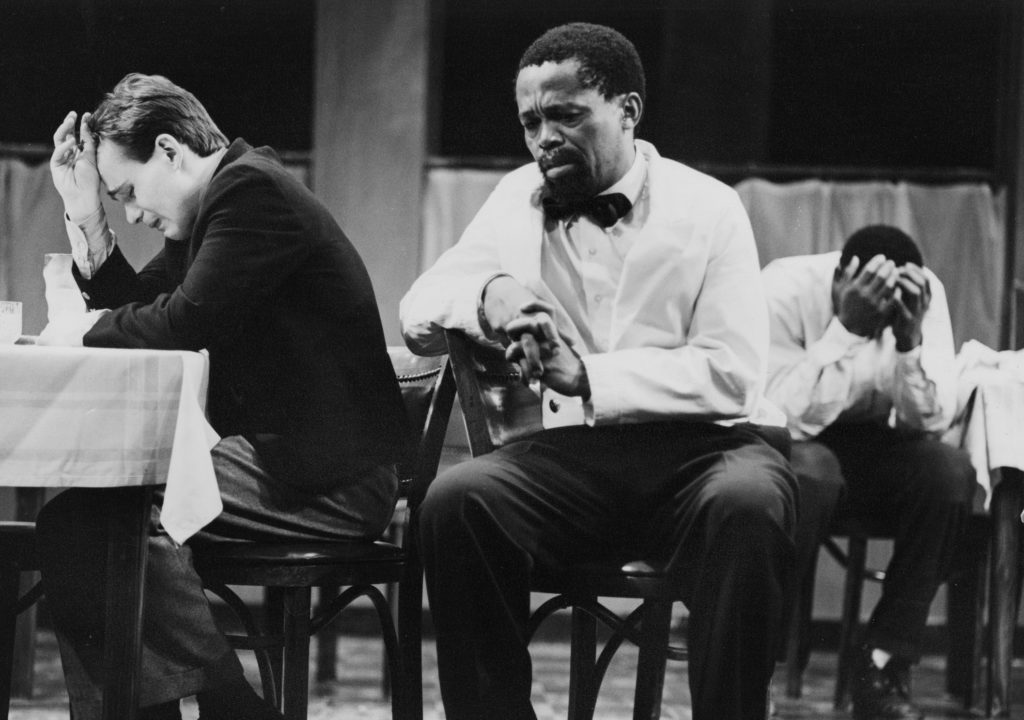

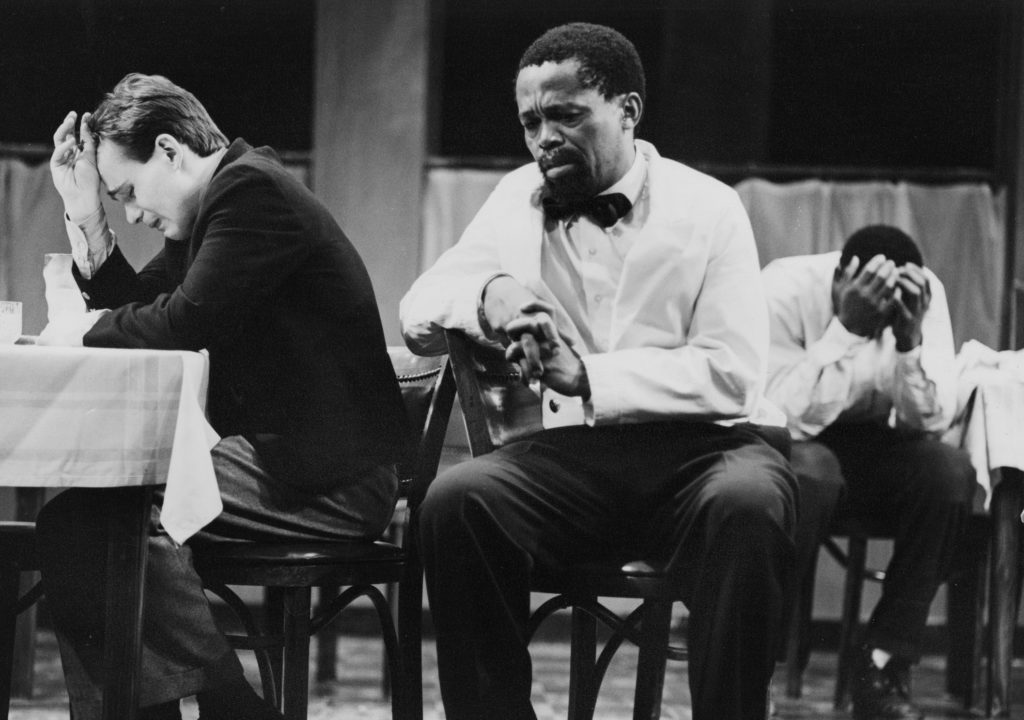

Željko Ivanek, Zakes Mokae and Danny Glover in the 1982 U.S. premiere of Athol Fugard’s “MASTER HAROLD …and the boys” at the Yale Repertory Theatre (photo by Gerry Goodstein)

After its US debut at Yale Repertory Theatre in March 1982, and before it opened on Broadway in early May of that year, Athol Fugard’s MASTER HAROLD…and the boys played a one-week engagement at the Annenberg Center in Philadelphia. During that brief run, one critic wrote of the play, in part:

Fugard, who also directed the Yale Repertory Theater production, has fashioned a play of compactness and clarity. Running without intermission for a rapid one-and-three-quarter hours, the play manages to develop and destroy this idyllic refuge for Hally while still taking time to comment on the human condition. To Fugard, life is a ballroom dance, but the humans who are on the floor are often tragically unaware of the steps.

The cast is exemplary. Danny Glover, with a minimum of dialogue, creates in Willie an admirable man whose emotions are obviously trapped by the racial system that restricts him. As Hally, Lonny Price captures the essence of a youth caught between two fathers and the pains of growing up. Price, who has replaced the explosive Željko Ivanek from the original Yale production, brings a gentle and more melancholy tone to the character of this young and misguided protagonist.

Dominating the show is Zakes Mokae as Sam. Mokae provides an ideal father figure for Hally, a man who painfully endures the insults of his “son” in an attempt to salvage the boy’s self-respect.

I recall this review distinctly because I wrote it. I also remember fighting angrily to insure that it appeared in The Daily Pennsylvanian, my college newspaper, because having seen the original run at Yale, I believed Master Harold to be a major work of theatre that students should know about. However, because my actual “beat” was writing theatre and film reviews of activities off-campus for the weekly entertainment magazine, 34th Street, shows at the on-campus Annenberg Center were the purview of others – though no one had asked to or been assigned to cover Master Harold. In some ways, it was a conflict of interest for me to write about Annenberg shows, because my work-study job was in the box office there, and in addition I had taken over running the Center’s post-show discussion series.

My fight to write about Master Harold was less because I was so eager to opine on it, but because I thought better me than no one. That’s not to say the play was struggling up from obscurity. On the same page where my review appeared there was an ad for the production, noting positive reviews by, among others, Frank Rich and Mel Gussow of The New York Times, Jack Kroll of Newsweek and Douglas Watt of the New York Daily News. But I doubt many Penn students at the time, even the theatre crowd, had read those.

I met Fugard that week in 1982 when he was on campus, albeit briefly, when I led a post-matinee discussion with him (two years earlier, also at Yale Rep, in a fleeting opportunity for me, he had signed my copy of A Lesson From Aloes). The event was to a degree derailed, first by the retirees in attendance, who used the opportunity to chastise the many high schoolers present for their inappropriate behavior during a pivotal moment in the play. Then more responsible students then took offense and spoke out to distance themselves from their less mature peers. Let’s just say I had no quality time with Athol on stage or off, as he disappeared immediately after the talk, which had squandered his presence.

It would be 28 years before I had the opportunity to speak with Fugard again, occasioned by my podcast “Downstage Center.” I had long wanted to talk with him, to revisit the Master Harold that I had seen both in New Haven and Philadelphia, and later on its national tour. Despite the fact that Fugard continued his relationship with Yale Rep into the latter part of the 80s, even as I began to work at Harford Stage, our paths never crossed, until October of 2010 for the podcast session.

Based upon what I had seen in 1982, I had been harboring a long unanswered question. However, what I wanted to discuss was so specific, that I didn’t bring it up during the 65 minute interview (which you can listen to here), because so few listeners might be interested. But once I turned off the recorder, I finally had my chance. I asked Fugard if he minded answering a very particular question almost three decades on, and he generously encouraged me.

As it was widely acknowledged, at the time and ever since, Ivanek could not stay with Master Harold because he was already committed to appear in a movie, The Sender, his first significant film role. Lonny Price, as he told me himself both back in 1982 at the Annenberg Center and again when we met as adults years later, had gone into the show with only 10 days preparation.

But as I intimated in my review, there was a shift in the play with the change from Ivanek to Price. Specifically (and if you don’t know the play, you may want to stop reading now), at its climax, Hally (as Harold is called throughout the play), spits on Sam, his surrogate father, and the two must confront the anger and shame that brought them to that moment and its aftermath. The play ends relatively quickly thereafter, with Hally making an emotional departure from the tea room where the play is set.

“When Željko played the role,” I related to Fugard in 2010, “it felt to me like there had been an irrevocable break. That Hally had become his father, embittered and racist, and that his friendship with Sam would never be repaired. With Lonny in the role, the moment seemed to be one that was more ambiguous, more confused, and even though he stormed off, you had a sense that they might work things out. Was that,” I then asked, “simply the result of the differing nature of the two actors, or was it a change in the intent of the moment and the play?”

“Well, the second way is truer to what really happened,” Fugard explained. As he had said previously in interviews over the years, he was Hally and there was a Sam. However the actual incident had taken place when Fugard was younger, a pre-teen, as opposed to the older teen as portrayed in the play. “We did become friends again,” he said.

“But,” he mused, “what you say is very interesting. Because what we ended up showing may have been the truth, but what you saw originally may have actually been the more dramatically interesting choice. I didn’t necessarily see it, because I knew what happened and that’s what I wanted to show. But perhaps I missed an opportunity.” And with that, since I had already kept Fugard past my allotted time, he was whisked off to some event where he was slated to put in an appearance.

I tell this story in part because while my question was birthed in 1982, it was with perseverance and luck that I was able to get an answer in 2010 – and because that’s an awfully long time to walk around with what was, in essence, a burning dramaturgical inquiry. But I also tell it because, for the first time in some 30 years, I’ll be seeing MASTER HAROLD…and the boys later this week at Signature, in a production once again directed by Fugard. Having seen it so often, and done so well, in the first half of the 1980s (including with James Earl Jones as Sam in the national tour), I have shied away from subsequent productions – and I wasn’t yet living in NYC when Lonny Price directed a revival for Roundabout in 2003. I’ve also never seen the TV version with Matthew Broderick, John Kani and Mokae from 1985 or the 2011 film (directed by Price) with Ving Rhames and Freddie Highmore.

It is now six years since I interviewed Athol, 34 years since I first saw Master Harold, and a few days before I see the play again. Perhaps Athol will be lurking at the back of the house, since I’m seeing a late preview; even if he is, I doubt he’ll remember me after our three brief meetings spread over so many years. I find myself wondering about what Hally I’ll see: the one who eventually reconciles with his friends or the one hardened into racism fueled by apartheid, or someone in between. But no matter what, I’m ready to spend an afternoon in the tea room with Willie, Hally and Sam, all of whom were theatrical mentors to me, teaching me how much one actor, and a shift in emphasis, can so change a play.

I am not given to reveries about bygone days or a review of my life choices on my birthdays. The same holds true for New Year’s eve and day. But just in time for my birthday this year, I was forced to look back on a small portion of my past, thanks to an archiving project undertaken by my college newspaper at the University of Pennsylvania. I suspect that many other alumni of The Daily Pennsylvanian are having this experience right now. It just so happens that its debut timed out just prior to my birthday.

I am not given to reveries about bygone days or a review of my life choices on my birthdays. The same holds true for New Year’s eve and day. But just in time for my birthday this year, I was forced to look back on a small portion of my past, thanks to an archiving project undertaken by my college newspaper at the University of Pennsylvania. I suspect that many other alumni of The Daily Pennsylvanian are having this experience right now. It just so happens that its debut timed out just prior to my birthday.

From roughly September 1981 to April of 1984, I wrote for The DP, after breaking through the cliquish barrier that didn’t afford me much opportunity during my freshman year. But once I began writing in earnest, I turned out some 70 pieces over three school years, a pretty good count considering my writing was limited almost entirely to 34th Street, a weekly magazine insert to the main paper where I was also arts editor for two semesters. Unlike the main newspaper, 34th Street of that era was focused on news and entertainment beyond the campus itself.

With my friend John Marshall (l.) at an annual DP dinner circa 1982

It’s worth noting that at the time I wrote for The DP, the internet was inconceivable and there was no prospect that my writing would last more than a couple of days, save for a few bound volumes that might gather dust in the paper’s archives. While I do have a stack of old papers stashed away in a drawer, I never anticipated that my thoughts on entertainment from ages 19 to 22 would ever be generally available to those who wished to seek them out.

Of course, dipping into the archive proved irresistible, and I quickly discovered pieces I remembered rather well, notably my first celebrity interview, with a not yet knighted Ian McKellen, which I had retyped and added to this website a few years ago. I found a number of film and theatre reviews, all written with the hauteur and certainty that one can perhaps only muster at that age. But as I browsed headlines, I was quickly reminded of some pieces, despite a distance of over 30 years, while others were so unfamiliar that I wondered if someone else had written them.

The most surprising pieces are the ones where, while my language may have been infelicitous and is now outmoded, with some unintentional sexism in evidence, it seems my perspective on the arts wasn’t all that different from what it is today. These are the ones from which I want to share a few bits and pieces.

In March 1982, I attempted to address both student performers and critics, tired of the endlessly repeated patterns of a review one day, followed by outraged letters from the subjects of those reviews a couple of days later. In “For Reviewers and Reviewees,” I counseled critics:

If you feel that there is something wrong with a show, say so, but don’t be nasty about it. The search for exciting prose should not extend to slandering the performers. They are, after all, fellow students. A negative observation about an actor is fine, but avoid excess, it does neither the performer’s nor your reputation any good.

Lights, sets, costumes, and, most importantly, direction are all critical elements of a show and involve great commitments by those responsible. These factors of production deserve much more than an offhand summation of “good” or “bad.”

To provide balance, I advised those involved in student theatre:

Remember that the reviewers also try to be as professional as possible. That means they must say what they feel, be it pleasant or uncomplimentary. Just as a director can choose to emphasize any facet of a script in production, a writer can focus on any element of a show that he deems worthy of mention.

Getting reviewed is an unavoidable part of performing (unless a producer decides not to let reviewers in). Right or wrong, intelligent or irresponsible, reviews are almost inextricably linked to the performing arts. Also, reviewers must speak with authority, since only they can justify the personal opinions that they write about. If a writer hates, for example, the score of West Side Story, he should say so, regardless of what anyone else thinks.

Two days after he received the Pulitzer Prize in 1982 for A Soldier’s Play, I had the opportunity to attend a small press gathering with Philadelphia resident Charles Fuller, held at Freedom Theatre, a company focused on work by African-American artists. I reported the event, in part, as follows:

Fuller says that at first he wasn’t sure everyone would like A Soldier’s Play, which is currently being staged by New York City’s Negro Ensemble Company. “We wanted to take a chance,” he says. “It begins to deal with some of the complexities of black life in this country.”

Fuller is only the second black playwright to win the prize. “It’s an important step for me as a playwright – I don’t know what effect it will have on theater as a whole.” As for Fuller’s own effect on theater, he wants to “talk about black people as human beings. We’ve been talked about as statistics for so long.”

Fuller says that his writing develops from his hopes for society. “It’s a severe racial pride. But it’s not racist.”

I presumed to opine about the state of Philadelphia theatre from a historical perspective, in the days before many of the vibrant companies that now occupy the city had begun. This was hubris, of course. But take note of my concern about ticket pricing.

Philadelphia theater ain’t what it used to be. Thank God.

After skyrocketing financial restraints severely depleted the number of pre-Broadway tryout productions here, Philadelphia in the 1970’s was left with but a few large Broadway-type houses and very little to put in them. Smaller companies tried in vain to bridge the gap, failing for a variety of economic and artistic reasons. And Andre Gregory’s Theatre of the Living Arts – the city’s only interesting theater of the 60’s – got too weird for patrons and fizzled out over a decade ago.

Pre-Broadway tours still come around every so often, with Anthony Quinn’s Zorba revival highlighting the past season and an Angela Lansbury Mame promised for the summer. Less discriminating theatrical patrons will probably be sated with the national tours that appear regularly with watered-down versions of Broadway smash hits, although paying 35 dollars for Andy Gibb in the otherwise wonderful Joseph and The Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat should be considered a criminal offense.

I had the opportunity to interview Spalding Gray, relatively early in his solo performing career, in conjunction with one of his monologues that few people have even heard of. It was performed at a venue called The Wilma Project, now known at The Wilma Theatre.

“I am a sort of actor-anthropologist, a mixture of story-teller and monologuist,” Gray says, summing up his unique performing style. He talks directly to the audience from memory, using no script. Unlike previous one-man shows. Gray portrays no one other than himself as he “re-remembers” his life experiences for audiences.

Gray will deliver his piece, In Search of the Monkey Girl, for a live audience the first lime this weekend. He has performed it four times into a tape recorder, in order to provide a text for a series of sideshow photographs shot by Randall Leverson which were printed in Aperture magazine. “It was strange,” Gray says. “He had worked for ten years and I only took ten days.”

In the course of his journey to the state fair, Gray was attracted to a trio of middle class preachers. “They had lost their drug rehabilitation center as a result of the Reagan cutbacks and were working in the sideshow in order to save up enough money to reopen it.” he says. In the meantime, Gray adds, “they were geeks, sucking on the heads of fifteen foot snakes.”

I am glad to find that I was concerned about the portrayal of women on screen at a young age (while completely misunderstanding a film’s genre), writing the following about 48 HRS, the Walter Hill movie that introduced Eddie Murphy to the big screen:

Compounding this inept rehash of the hard-boiled detective genre is the incredibly sexist treatment of women. The few females presented are either climbing into or out of bed, making 48 HRS the most callously anti-feminist film in years.

Even live theatre, or taped productions, something that is once again a current topic, caught my eye, and my thoughts today aren’t all that different than these from 1982:

First, in the case of NBC’s offerings, is it really necessary for T.V. to air the programs live? Granted, live productions were the rule in the fifties, but now editing allows for choosing the best of many takes. Finer quality could be attained from editing together several different performances of the same work. Nowadays live broadcasts are novelties masquerading as high art.

Second, judging by the cable tapings of stage shows, can true justice be done to a work that is primarily staged for one viewing perspective? The limitations imposed by stage architecture result in a radical lessening of camera angles, which have traditionally been used by T.V. and cinema to add to a production. One play shown on HBO included shots from the back of the theater, rendering the figures on the stage almost invisible. Stage shows should be directed again if they are to be adapted for the camera.

Third, what of realism: will a T.V. audience accept “theatricality’?…

…It is commendable that T.V. is attempting to bring theater to a mass audience, but it is a shame that the artistic qualities and capabilities of both media are being compromised in the process. While the public should strongly support the revival of television drama, perhaps theater is belter off where it belongs: on the stage.

I do remember my lengthy feature on the issue of book banning and censorship, which presaged some of my work at the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School on arts censorship. I spoke with figures I didn’t care for at the time (and still don’t), such as Phyllis Schlafly and a spokesman for Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority. Frankly, I wish I’d spoken to more anti-censorship figures as I look back at the article, but my summing up wasn’t bad, though I deeply regret the absence of two asterisks at the time, or my use of a racial slur at all, when referring to Mark Twain’s character of Jim in Huckleberry Finn:

In Texas this past August, a couple who spend their time reviewing school books for “questionable” content voiced disapproval of a textbook that describes the medicinal qualities of the drug insulin. They said that the reference will lead students to believe that all drugs are sale and beneficial.

Earlier this year Studs Turkel visited a high school in Girard, Pennsylvania, to talk with students and teachers about the movement to remove Working from twelfth grade reading lists. His appearance convinced authorities to restore the book temporarily, but they are still seeking a means by which Working can be banned.

The above examples are not isolated incidents. The rapidly rising wave of book banning and censorship threatens to engulf the U.S.’s entire elementary and secondary education system. There are ten times as many books banned today as there were only a decade ago. Books are being withheld or purged from classrooms and school libraries according to the dictates of various parental and political interest groups…

…No matter how big the issue becomes, the controversy boils down to three issues; what rights the Constitution guarantees to students, what parents want their children to read, and what censorship means. Is it the removal of traditional values from books or the removal of books from libraries? And who will decide?

Finally, in a piece I had completely forgotten, I find that my work at the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts was not something that emerged late in life, but had actually been on my mind a long time ago as well. It’s important to remember that at the time, “handicapped” was still emerging to replace “crippled”; “disabled” was not yet identified as the best term. There’s some hyperbole here, and outmoded and awkward expression, but the core of my thinking, I hope, rings true.

An actor’s greatest fear, short of death, is probably of being disfigured in some terribly obvious way. A facial scar, a missing limb, even something so simple as nodes on the vocal cords can send the finest actor into oblivion. But a handful of actors over the past several decades have proven that the handicapped are still superb performers who do not deserve to be shunned by an industry that has based itself on physical perfection…

…Currently, Adam Redfield is touring in the play Mass Appeal, despite an obvious case of neuralgia which has paralyzed the right side of his face. While the condition is temporary, it is to the producers’ credit that they have allowed Redfield to continue in the role. It also proves that the handicapped should be allowed to perform in “normal” roles, even if they do not quite fit the character description, it is sobering to remember that had Redfield had the neuralgia before his audition, he probably would have been quickly discarded.

Are we fully formed as people in college? Certainly not. But it seems that many of the same interests and issues that moved me to to write 30 years ago remain important to me now. I wonder if anything I said in the 80s, or today, will still hold up another 30 years on. But I’d like to still be writing, and I wonder what will be in my mind in 2046.

I am not given to reveries about bygone days or a review of my life choices on my birthdays. The same holds true for New Year’s eve and day. But just in time for my birthday this year, I was forced to look back on a small portion of my past, thanks to an

I am not given to reveries about bygone days or a review of my life choices on my birthdays. The same holds true for New Year’s eve and day. But just in time for my birthday this year, I was forced to look back on a small portion of my past, thanks to an