October 14th, 2014 § § permalink

Aside from being the month of copious pumpkin flavored foodstuffs, October also brings two perennial theatrical top ten lists that are worthy of note: American Theatre magazine’s list of the most produced plays in Theatre Communications Group theatres for the coming season and Dramatics magazine’s lists of the most produced plays, musicals and one-acts in high school theatre for the prior year. They both say a great deal about the state of theatre in their respective spheres of production, both by what’s listed explicitly, as well as by what doesn’t appear.

In the broadest sense, both lists are startlingly predictable, although for different reasons. If you happen to find a bookie willing to give you odds on predicting the lists, here’s the trick for each: for the American Theatre list, bet heavily on plays which appeared on Broadway, or had acclaimed Off-Broadway runs, in the past year or two. For the Dramatics list, bet heavily on the plays that appeared on the prior year’s list.

But in the interest of learning, let’s unpack each list not quite so reductively.

American Theatre

As I’ve written in the past, what happens in New York theatre is a superb predictor of what will happen in regional theatre in the coming seasons, especially when it comes to plays. Any play that makes it to Broadway, or gets a great New York Times review, is going to grab the attention of regional producers. Throw in Tony nominations, let alone a Tony win – or the Pulitzer – and those are the plays that will quickly crop up on regional theatre schedules.

As I’ve written in the past, what happens in New York theatre is a superb predictor of what will happen in regional theatre in the coming seasons, especially when it comes to plays. Any play that makes it to Broadway, or gets a great New York Times review, is going to grab the attention of regional producers. Throw in Tony nominations, let alone a Tony win – or the Pulitzer – and those are the plays that will quickly crop up on regional theatre schedules.

Anyone who follows the pattern of production would have easily guessed that Christopher Durang’s Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike would proliferate this year, being a thoughtful, literary based comedy with a cast of only six. That American Theatre lists 27 productions doesn’t even take into account the 11 theatres that did the show in 2013-14, and certainly there are non-TCG theatres which are doing the show as well. It’s no surprise that Durang has said he made more money this past year than in any other year of his career; it’s a shame that financial success has taken so long for such a prodigiously gifted writer and teacher.

In general, shows on the American Theatre list have about a three year stay, typically peaking in their second year on the list, but this can vary depending upon when titles are released by licensing houses and agents to regional theatres. 25 years ago (and more significantly years before that) theatres might have had to compete with commercial tours, but play tours are exceedingly rare birds these days, if not extinct.

Perhaps this rush to the familiar and popular and NYC-annointed is disheartening, but it’s worth observing that the American Theatre list notes how many productions each title gets, and that after the first couple of slots, we’re usually looking at plays that are getting 7 or 8 productions in a given season, across TCG’s current universe of 474 member companies (404 of which were included in this year’s figures). Since the magazine notes a universe of 1,876 productions, suddenly 27 stagings of a single show doesn’t seem so dominant after all. Granted, TCG drops Shakespeare from their calculations, but even he only counted for 77 productions of all of his plays across this field. So reading between the lines, the American Theatre list suggests there’s very little unanimity about what’s done at TCG member theatres in any given year, a less quantifiable achievement but an important one.

Perhaps this rush to the familiar and popular and NYC-annointed is disheartening, but it’s worth observing that the American Theatre list notes how many productions each title gets, and that after the first couple of slots, we’re usually looking at plays that are getting 7 or 8 productions in a given season, across TCG’s current universe of 474 member companies (404 of which were included in this year’s figures). Since the magazine notes a universe of 1,876 productions, suddenly 27 stagings of a single show doesn’t seem so dominant after all. Granted, TCG drops Shakespeare from their calculations, but even he only counted for 77 productions of all of his plays across this field. So reading between the lines, the American Theatre list suggests there’s very little unanimity about what’s done at TCG member theatres in any given year, a less quantifiable achievement but an important one.

Dramatics

While titles come and go on the American Theatre list, stasis is the best word to describe the lists of most produced high school plays (it’s somewhat less true for musicals). Nine of the plays on the 2014 list were on the 2013 list; 2014 was topped by John Cariani’s Almost, Maine, followed by A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the two titles were in reverse order the prior year. The other duplicated titles were Our Town, 12 Angry Men (Jurors), You Can’t Take It With You, Romeo and Juliet, The Crucible, Harvey and The Importance of Being Earnest.

While titles come and go on the American Theatre list, stasis is the best word to describe the lists of most produced high school plays (it’s somewhat less true for musicals). Nine of the plays on the 2014 list were on the 2013 list; 2014 was topped by John Cariani’s Almost, Maine, followed by A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the two titles were in reverse order the prior year. The other duplicated titles were Our Town, 12 Angry Men (Jurors), You Can’t Take It With You, Romeo and Juliet, The Crucible, Harvey and The Importance of Being Earnest.

Like the American Theatre list, the Dramatics survey doesn’t cover the entirety of high school theatre production; only those schools that are members of the Educational Theatre Association’s International Thespian Society have the opportunity to participate, representing more than 4,000 high schools out of a universe of 28,500 public, private and parochial secondary schools in the country. Unlike the Dramatics list, there are no hard numbers about how many productions each show receives, so one can only judge relative popularity.

Almost, Maine’s swift ascension to the top rungs of the list is extraordinary, but it’s due in no small part to its construction as a series of thematically linked scenes, originally played by just four actors but easily expandable for casts where actor salaries aren’t an issue. Looking at recent American Theatre lists, they tend to be topped by plays with small casts (Venus in Fur, Red, Good People and The 39 Steps), while the Dramatics list is the reverse, with larger cast plays dominating, in order to be inclusive of more students (though paling next to musicals where casts in school shows might expand to 50 or more).

Almost, Maine’s swift ascension to the top rungs of the list is extraordinary, but it’s due in no small part to its construction as a series of thematically linked scenes, originally played by just four actors but easily expandable for casts where actor salaries aren’t an issue. Looking at recent American Theatre lists, they tend to be topped by plays with small casts (Venus in Fur, Red, Good People and The 39 Steps), while the Dramatics list is the reverse, with larger cast plays dominating, in order to be inclusive of more students (though paling next to musicals where casts in school shows might expand to 50 or more).

The most important trend on the Dramatics list (which has been produced since 1938) is the lack of trends. Though a full assessment of the history of top high school plays would take considerable effort, it’s worth noting that Our Town was on the list not only in 2014 and 2013, but also in 2009, 1999 and 1989; the same is true for You Can’t Take It With You. Other frequently appearing titles are Arsenic and Old Lace, various adaptations of Alice in Wonderland, Harvey, and The Miracle Worker.

No doubt the lack of newer plays with large casts is a significant reason why older classic tend to rule this list; certainly the classic nature of these works and their relative lack of controversial elements play into it as well. But as I watched Sheri Wilner’s play Kingdom City at the La Jolla Playhouse a few weeks ago, in which a drama director is compelled to choose a play from the Dramatics list, I wondered: is the list self-perpetuating? Are there numerous schools that seek what’s mainstream and accepted at other schools, and so do the same plays propagate themselves because administrators see the Dramatics list as having an implied educational seal of approval?

That may well be, and if it’s true, it’s an unfortunate side effect of a quantitative survey. But it’s also worth noting that many of these plays, vintage though they may be, have common themes, chief among them exhortations to march to your own drummer, to matter how out of step you may be to the conventional wisdom. They may be artistic expressions from other eras about the importance of individuality, but in the hands of teachers thinking about more than just placating parents, they are also opportunities to celebrate those among us who may seem different or unique, and for fighting for what you believe in against prevailing sentiment or structures.

* * *

Looking at musicals on the American Theatre list is a challenge, because their list is an aggregate of plays and musicals, and while many regional companies now do a musical or two, it’s much harder for any groundswell to emerge. In the last five years, only three musicals have made it onto the TCG lists, each for one year only: Into The Woods, Spring Awakening and The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee. That doesn’t mean there’s a dearth of musical production, it simply shows that the work is being done by companies outside of the TCG universe.

Musicals are of course a staple of high school theatre, but the top ten lists from Dramatics are somewhat more fluid. While staples like Guys and Dolls, Grease, Once Upon a Mattress, You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown and Little Shop of Horrors maintain their presence, newer musicals arrive every year or two, with works like Seussical, Legally Blonde, Spelling Bee, and Thoroughly Modern Millie appearing frequently in recent years. At the peak spot, after a six-year run, Beauty and the Beast was bested this year by Shrek; as with professional companies, when popular new works are released into the market, they quickly rise to the top. How long they’ll stay is anyone’s guess, but I have little doubt that we’ll one day see Aladdin and Wicked settle in for long tenures.

Musicals are of course a staple of high school theatre, but the top ten lists from Dramatics are somewhat more fluid. While staples like Guys and Dolls, Grease, Once Upon a Mattress, You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown and Little Shop of Horrors maintain their presence, newer musicals arrive every year or two, with works like Seussical, Legally Blonde, Spelling Bee, and Thoroughly Modern Millie appearing frequently in recent years. At the peak spot, after a six-year run, Beauty and the Beast was bested this year by Shrek; as with professional companies, when popular new works are released into the market, they quickly rise to the top. How long they’ll stay is anyone’s guess, but I have little doubt that we’ll one day see Aladdin and Wicked settle in for long tenures.

* * *

When I looked at both the American Theatre and Dramatics lists over a span of time, the distinct predictability of each was troubling. Coming out when they do, before most theatrical production for the next theatre season is set, I’d like to see them looked at not as any manner of affirmation, but as a challenge – whether to professional companies or school schedules. I admire and enjoy the plays that are listed here, and nothing herein should be construed as critical of any of these shows; audiences around the country deserve the opportunity to see them. While I do have the benefit of living in New York and seeing most of these popular shows there, I must confess that I am most intrigued by the theatre companies and school groups that might just say to themselves, ‘Let’s not do the shows, or too many of the shows, that appear on these lists. Let’s find something else.’ Those plays may never appear as part of any aggregation, but I suspect the groups’ work will be all the more interesting for it, benefiting both artists and audiences.

October 30th, 2013 § § permalink

Position 1: a stage production that is recorded, filmed or actually broadcast live ceases to be theatre. It may be considered television or film, but it is a record of theatre, not the thing itself. True theatre is experienced in the flesh, so to speak.

Position 2: for people who have no means to see any theatre, or a specific production, a recording or live transmission of the event, whether it occurs in a movie theatre or on a computer, is better than not seeing it at all, provided it is at least competently produced.

Position 3: even though it means I don’t get to see some things that really interest me, I don’t enjoy recorded theatre, no matter how artfully done, and I’m lucky enough to have access to lots of great theatre live, so after a few tries, I now don’t go. But that shouldn’t stop anyone else.

Why have I laid out these positions so baldly, rather than making a case for them? Because I want to talk about an aspect of the growing appetite for cinecasts, NT Live, the home delivery Digital Theatre and the like that isn’t about the viewing experience at all. That’s a matter of opportunity and preference and I leave it to everyone else to hash out those issues. My interest in this trend is about how it is branding certain cultural events and producers – and how U.S. theatre is quickly losing ground.

Why have I laid out these positions so baldly, rather than making a case for them? Because I want to talk about an aspect of the growing appetite for cinecasts, NT Live, the home delivery Digital Theatre and the like that isn’t about the viewing experience at all. That’s a matter of opportunity and preference and I leave it to everyone else to hash out those issues. My interest in this trend is about how it is branding certain cultural events and producers – and how U.S. theatre is quickly losing ground.

In general, people attend commercial theatre based upon the appeal of a production – cast, creative team, author, reviews, word of mouth, etc. Who produced a show is pretty much irrelevant, and only theatre insiders can usually tell you who produced any given work. In institutional theatre, the producer has more impact, as people may attend because they have enjoyed a company’s work previously, because it conveys a certain level of quality. This is true in major cities and regionally, and while the name of the theatre alone isn’t sufficient for sales, it is a factor in a way it isn’t in the West End or on Broadway.

As a result, what is happening with theatrecasts is that the reach of the companies utilizing this opportunity is vastly extended, and the brands of the companies travel far beyond those who sit in their seats or regularly read or hear about their work. There’s long been prestige attached to The Royal Shakespeare Company, the Metropolitan Opera and the National Theatre; now their presence in movie theatres has served to increase access and awareness. These longstanding brands are being burnished anew now that more people can actually see their work. The relatively young Shakespeare’s Globe, even as it makes its Broadway debut, is also gaining recognition thanks to recordings of their shows.

As a result, what is happening with theatrecasts is that the reach of the companies utilizing this opportunity is vastly extended, and the brands of the companies travel far beyond those who sit in their seats or regularly read or hear about their work. There’s long been prestige attached to The Royal Shakespeare Company, the Metropolitan Opera and the National Theatre; now their presence in movie theatres has served to increase access and awareness. These longstanding brands are being burnished anew now that more people can actually see their work. The relatively young Shakespeare’s Globe, even as it makes its Broadway debut, is also gaining recognition thanks to recordings of their shows.

It should be noted that for UK companies, “live” is a misnomer when it comes to North American showings. We’re always seeing the work after the fact, given the time difference, so in many ways it’s no different than a pre-recorded stage work on PBS. But the connotation of live is a valuable imprimatur, and few seem to mind it, even when there are “encore” presentations of shows from prior years. The scale of a movie screen, the quality of a cinema sound system appear to be the true lure, along with the fact that these are not extended engagements, but carefully limited opportunities that don’t compete with actual movie releases.

MEMPHIS, one of the rare U.S. originated cinecasts

Regretfully, by and large, American theatre (and theatres) are missing the boat on this great opportunity for exposure, for revenue, for branding. There have been the occasional cinecasts (Memphis The Musical; Roundabout’s Importance of Being Earnest, imported from Canada’s Stratford Festival) but they’re few and far between. We’re about to get a live national television broadcast of the stage version of The Sound of Music, but it’s an original production for television, not a stage work being shared beyond its geographic limitations. Long gone are the days when Joseph Papp productions of Much Ado About Nothing and Sticks And Bones were seen in primetime on CBS; when Bernard Pomerance’s The Elephant Man was produced for ABC with much of the original Broadway cast; when Nicholas Nickleby ran in its entirety on broadcast TV; when PBS produced Theatre in America, showcasing regional productions, when Richard Burton’s Hamlet was filmed on Broadway for movie theatre showings 50 years ago.

London MERRILY rolled across the Atlantic

Most often, when this topic comes up in conversations I’ve been party to, there’s grumbling about prohibitive union costs as a roadblock. Perhaps the costs have changed since the days of many of the examples I just cited, yet somehow Memphis and Earnest surmounted them. Even as someone who doesn’t particularly care to see these recorded stage works, I worry that American theatre is lagging our British counterparts in showcasing work nationally and internationally, in taking advantage of technology to advance the awareness of our many achievements. Seeing an NT Live screening has become an event unto itself – this week the National’s Frankenstein is back just in time for Halloween; the enthusiasm last week for the cinecast of Merrily We Roll Along (from the West End by way of the Menier Chocolate Factory) was significant, at least according to my Twitter and Facebook feeds. The appetite is also attested to by an online poll from The Telegraph in London, with 90% of respondents favoring theatre at the movies (concurrent with an article about the successful British efforts in this area). I’d like to see this same enthusiasm used not just to bring U.S. theatre overseas, but to bring Los Angeles theatre to Chicago, Philadelphia theatre to San Francisco, Seattle theatre to New York, and so on – and not just when a show is deemed commercially viable for a Broadway transfer or national tour.

I’m not trying to position this as a competition, because I think there’s room for theatre to travel in all directions, both at home and abroad. But without viable and consistent American participation in the burgeoning world of theatre on screen, we run the risk of failing to build both individual brands and our national theatre brand, of having our work diminished as other theatre proliferates in our backyards, while ours remains contained within the same four walls that have always been its boundaries and its limitations. Somebody needs to start removing the obstacles, or we’re going to be left behind.

September 19th, 2013 § § permalink

“Stanley? Is that you?”

A very good friend of mine began a successful tenure as the p.r. director of the Long Wharf Theatre in 1986, one year after I’d taken up the comparable position at Hartford Stage. He came blazing out of the gate with a barrage of stories and features in the first few months he was there. But as their third play approached, he called me for some peer-to-peer counseling. With a worried tone, he said, “Howard, my first show was All My Sons with Ralph Waite of The Waltons. My second show was Camille with Kathleen Turner. Now I’ve just got a new play by an unknown author without any stars in it. What do I do?”

My reply: “Welcome to regional theatre.”

Now as that anecdote makes clear, famous names are hardly new in regional theatre, though they’re somewhat infrequent in most cases. In my home state of Connecticut, Katharine Hepburn was a mainstay at the American Shakespeare Theatre in the 1950s, a now closed venue where I saw Christopher Walken as Hamlet in the early 80s. The venerable Westport Country Playhouse ran for many years with stars of Broadway and later TV coming through regularly; when I worked there in the 1984 and 1985 seasons, shows featured everyone from Geraldine Page and Sandy Dennis to David McCallum and Jeff Conaway. I went to town promoting Richard Thomas as Hamlet in 1987 at Hartford. The examples are endless.

So I should hardly be surprised when, in the past week, I have seen a barrage of coverage of Yale Repertory Theatre’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire with True Blood’s Joe Manganiello, or Joan Allen’s return to Steppenwolf, for the first time in two decades, in The Wheel. Indeed, I make the assumption, even the assertion, that they were cast because they were ideal for their roles, not out of any craven attempt to boost box office (Manganiello has even played the role on stage before, and of course Allen is a Steppenwolf veteran). I truly hope they both have great successes. But the stories are coming fast and furious (here’s an Associated Press piece on Allen and an “In Performance” video with Manganiello from The New York Times).

I have to admit, what once seemed a rare and wonderful opportunity to me as a youthful press agent gives me pause as a middle-aged surveyor of the arts scene. Perhaps it’s the proliferation of outlets that make these star appearances in regional theatre seem more heightened, with more attention when they happen. And that’s surely coupled with my ongoing fears about where regional arts coverage fits in today’s entertainment media priorities, which by any account are celebrity driven.

At a time when Broadway is portrayed as ever more star-laden (it has always been thus, but seems to have reached a point where a successful play without stars is the rarity), I worry that this same star-focus is trickling down. Certainly Off-Broadway is filled with “name” actors, so isn’t it reasonable that non-NYC companies would be desirous of the attention made possible by casting actors with the glow of fame? If Broadway maintains sales for plays by relying on stars, it’s not unreasonable for regional companies to want to compete in the same manner against the ongoing onslaught of electronic entertainment.

Again, I doubt any company is casting based solely by name, like some mercenary summer stock producer of bygone days, but one cannot help but worry about the opportunities for solid, working actors to play major leads when Diane Lane takes on Sweet Bird of Youth at The Goodman or Sam Rockwell plays Stanley Kowalski at Williamstown. Aren’t there veteran actors who deserve a shot at those roles? Yet why shouldn’t those stars, proven in other media, have the opportunity to work on stage, especially if it benefits nor-for-profit companies at the box office without compromising artistic integrity?

I’m talking out of both sides of my mouth here, and I know it. But I go back to the essence of my friend’s quandary back in 1986: what do regional theatres do when they don’t have stars? They go back to serving only their communities, which is their first and foremost priority, but they fall back off the radar of what remains of the national media that might allocate any space to stage work outside of New York. They have raised the expectations of their audiences, who love seeing famous folk in their town, on their stages, then can’t always meet them. Are theatres inadvertently contributing to a climate in which celebrity counts first and foremost? How then does the case get made for the perpetual value of the companies that either don’t – or never could – attract attention by working with big names.

Theatres play into this with their own marketing as well; it’s not solely a media issue. Even when they rigorously adhere to alphabetical company billing in programs and even ads, their graphics usually manage to feature famous faces (notably, Yale’s Streetcar does not). Though in some cases, even the billing barrier has fallen, acknowledging the foolishness in trying to pretend someone famous isn’t at the theatre, it grates a bit when regional theatres place actors “above the title” in ads or use the word “starring,” when ensemble was once the emphasis. When the season brochure comes out for the following season, or seasons, which actors seem to recur in photos, for years after their sole visit?

This past February, The New York Times placed a story about celebrity casting on its front page, as if it were something new, and ensuing reportage seemed to carry a whiff of condescension about the casting of stars in Broadway shows. Though when the Times‘ “The New Season” section came out two weeks ago, who was on the front page of it? James Bond – excuse me, Daniel Craig. Celebrity counted there as well. Because it sells.

In a week when Off-Broadway shows like The Old Friends, Mr. Burns and Fetch Clay, Make Man opened to very strong reviews, it’s worth noting that none featured big box office stars, and that as of yet, none have been announced for commercial transfers. Their quality is acknowledged, but perhaps quality alone is not enough to sustain the productions beyond their relatively small-sized venues. Time will tell. While that’s no failure, it suggests that theatre is evolving into two separate strata, unique from the commonly cited divisions of commercial/not-for-profit or Broadway/Off-Broadway/regional. Perhaps the new distinction for theatre has become “star” or “no-star.” And if that’s the case, I think it bodes ill for the health of not-for-profit companies, the vitality of audiences, and for anyone who seeks to spend their life acting, but may never get that TV show or movie that lifts them into the realm of recognition, or even higher, into fame.

Incidentally, can anyone say, quickly, who’s playing Blanche at Yale? Because, in case you forgot, the play is really about Blanche. Not the werewolf.

March 28th, 2013 § § permalink

“Hello? Do you have Tilda Swinton in a box?”

For a certain breed of relatively cultured wags (including the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright David Lindsay Abaire and, less exaltedly, me), Tilda Swinton sleeping in a glass box at the Museum of Modern Art is a comedic source that just keeps on giving. After all, this is an Academy Award-winning actor with a distinctly unique personal style ensconcing herself in a terrarium on random days for hours at a time. Modern art, performance art, personal eccentricity or creative vision – all grist for the humor mill. The piece has a name, incidentally — “The Maybe” — which only serves as a dog-whistle call to those who would poke fun at it; that Swinton first “performed” it in 1995 only increases the volume.

I freely admit I am unequipped to assess “The Maybe” as fine art or performance art. But in contrast to my own tweeted gibes and my enthusiastic embrace of David’s seemingly endless variations on the theme, I’d like to dispense with the humor and take the piece vaguely seriously, stipulating to the court that it is worthy of consideration, since experts have apparently deemed it as such.

If it is art of any stripe, why has it touched off such a sensation? If just anyone was asleep, or feigning sleep in a glass box at MOMA for hours at a time, it would be a curiosity, at best worthy of a squib on websites or the kicker story on local news. On occasion, I happen to talk with some coherence while I sleep, and I am known (by a very select few) to thrash about involuntarily as well; I’d be much more engaging lying in that box, but wouldn’t raise much media comment.

If there was no apparent air source to the box, this would rise to the dwindling level of interest of a David Blaine stunt. If there was an adorable kitty or puppy in the box it might find attention as an internet video, or arouse ire and concern over the animal’s treatment. If we learned someone was being paid $50,000 a night to do this, it might prove as enraging as the new Virginia bus stop that cost $1 million to build.

The only reason the general public knows about this piece of art is because Swinton already has a level of fame. She’s got that Oscar and she’s a highly respected actress, though hardly a household name. She might be called a star, but certainly not a celebrity; this isn’t Hasselhoff or a Kardashian lounging about on view. But Tilda’s well enough known to raise oddity into spectacle, more than willing to exploit her renown for this “work,” which has surely generated international headlines for MOMA this week. Let’s remember, when she did this in the 90s, she hadn’t yet gone toe to toe with Clooney onscreen.

Some of the same cultural outlets that are quick to question when “name” actors are announced for theatre productions have covered the Swinton event, and while they’ve noted its peculiarity, many have left the withering and witty comments to those on social media. Silly as the whole thing may seem, I feel they’ve given Swinton some leeway, while shows on and off-Broadway with famous actors are damned right out of the gate as “star-driven,” even when the actor is impeccably cast (admittedly, not all are). No one that I’ve seen has reported the weekend grosses at MOMA, despite their surprise deployment of a celebrity and the subsequent press; however, it is often implied that when a stage piece with a star in it does well at the box office, it has somehow cheated its way to success. Are there different standards for museums and theatres? Or am I just not tuned in to the art world?

To be a celebrity or to be a star, that is the question.

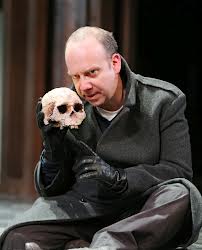

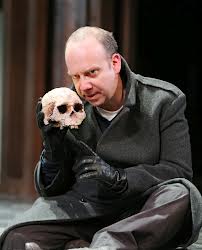

“The Maybe”’s emergence this weekend happened to coincide with the premiere of a new production of Hamlet at the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven. Perhaps you’ve heard about it? Normally, a regional production of Hamlet might not evoke much attention, but this one has lured the New York theatre press onto I-95 and Metro-North almost en masse. Why? Because the melancholy Dane is being played by the very fine actor Paul Giamatti, a screen stalwart little seen on stage in recent years. The announcement of the show generated the first wave of press, given the incongruity of his appearance and manner with most visions of the sweet prince; the performance itself has yielded many more reviews than a typical show at a Connecticut theatre.

Some of the outlets that rushed to see the “famous” Paul Giamatti as Hamlet are the same ones who rail against the damage celebrity casting has done to New York theatre, yet here they are responding to its siren call (along with audiences, who made the show a sell-out even before performances began). I’m not denigrating Giamatti’s considerable talents, but dollars to doughnuts some other fine actor, unexpected or not, but without copious entries on the IMDB, wouldn’t have taxed arts travel budgets. It would have been “just another regional theatre show,” left to the local press.

This is all a long way of saying that whether the box is a small glass display case or grand theatre, fame gets to the head of the media line, even when it comes to the arts, even in media that decry the ascendance of celebrity. I don’t begrudge MOMA or Yale Rep the attention they’re getting, but I wonder whether that attention may play into the hands of celebrity culture, saying to other organizations that they’ll get their shot at the spotlight when and if they too offer the media “names.” Will not-for-profits of every stripe, not just commercial enterprises, be driven towards stunts and stars, even if the examples I’ve given were staged with the utmost sincerity? Or can stardom be made secondary when contemplating the arts?

When we get a gift, part of the excitement is not knowing what’s in the box, the joy of discovery. But if the admittedly embattled media increasingly attends only to boxes – be they glass, canvas, concrete or brick and mortar – because they and we are already attracted to what’s inside, we’ll keep seeing more and more known quantities as companies vie for attention, and without it, it’ll be harder and harder to sustain work that retains the thrill of surprise.

March 20th, 2013 § § permalink

Humor me.

In the wake of my post yesterday about the pros and cons of theatre seasons looking like the New York season from the prior year, and some great responses to it, the beloved phrase “national conversation about theatre” keeps coming to mind. Surely you’ve heard this concept, the now decades-old plaint from theatre professionals of all stripes that media conversation can center on a movie, a book, even a song, but that – perhaps not since Angels in America – neither the act of making theatre nor any particular work of theatre has made that grade. Mind you, there are conversations within the field of great value; I’m talking about something that breaks past American Theatre, HowlRound, 2 AM Theatre, Twitter and other resources into the general public consciousness.

This is due to many factors, but surely one is the fragmentary nature of the American theatre. With each company choosing its season independently, there may be coincidences in programming, there may be a handful of select plays dotting the country over the course of a year or two. But in essence, outside of one’s own community, all theatre is a one-off. Perhaps, on occasion, a little – or a lot of – collusion would be a good thing.

By now we’ve all heard of communities that choose a book for a city-wide read, with a concerted effort to promote the idea that a metropolitan bonds if they can all have a conversation about the same thing. This has been going on for a number of years, though not in places where I’ve lived, so I can only admire it from afar, rather than share personal experience. But it is a compelling idea.

Am I now going to suggest everyone should read the same play? No. You’re getting ahead of me. While there’s some merit to that idea, theatre is meant to be seen. I’m thinking bigger.

I wonder whether, say, a dozen theatres, large and small, in different cities and towns, could agree on a single work of theatre (and I’d much prefer that it was a new work, not a classic revival), a play of social and political importance, that could be near-simultaneously produced across the country. Not a tour, not a handful of co-productions, but a whole bunch of theatres doing the same work within, say, an eight-week period.

Now I know that every theatre has to balance its season, struggles with its budget, weighs its logistics. I’m not saying it would be easy. But hear me out.

“Clybourne Park” at Playwrights Horizons

When Clybourne Park was first produced at Playwrights Horizons in 2011, it was followed within weeks by a production at Woolly Mammoth. The following season, it was featured in a number of seasons (as well as in London at the Royal Court), making it to Broadway for the spring and summer of 2012, and now playing in yet more cities in regional productions. Now imagine if all of those productions (sans Broadway, which is irrelevant to my proposal) happened in only a few months time. Think of the conversations that provocative play would have sparked. The same holds true for The Mountaintop, and Good People, and Ruined, and Chad Deity and many others.

A challenge? Yes. Impossible? No. Let us look to history. Specifically, A History of the American Film by Christopher Durang.

“A History of the American Film” at Arena Stage

In 1977, with Durang barely out of the Yale School of Drama, his pastiche of classic movies had a tripartite premiere, with productions in March and April of that year at the Mark Taper in Los Angeles, Arena Stage in DC, and Hartford Stage. It had been discovered in a workshop at The O’Neill the prior summer; it moved to Broadway, briefly, in 1978. But just imagine: a new play, by a tremendously talented up-and-comer, hitting a trifecta of productions out of the gate. I didn’t see it at the time (I was 14), but I sure remember reading about it.

If we want to be part of “the national conversation,” we have to look to a mashup of the Clybourne-History models, so the country will truly sit up and take notice, regardless of whether a New York berth is in the mix or not. We’ll either have to get over our deep desire to proclaim “world premiere” (or agree that everyone gets to say it); we’ll have to use a microtome to slice up the royalties normally given over to an originating company so everyone gets a share, but doesn’t overburden the play’s ongoing life; we’ll have to tacitly accept that the playwright might be working on the piece personally at only one theatre while revisions fly out to many. But remember that thanks to Skype and streaming video, the playwright can confer with disparate teams, and even look in on multiple rehearsals, without criss-crossing the country on planes. And no one need worry about cannibalizing audiences, since city to city overlap is fairly rare.

If many people are seeing the same play at once, we can at last have one show that’s reaching more people in a single night than any individual Broadway or touring show can; we’ll have a story that national press outlets can’t ignore; we’ll have a playwright who can dedicate themselves to working in theatre for a season without receiving an inheritance or a genius grant, since the collective royalties will be significant.

With theatres having just announced or on the verge of announcing their 2013-14 seasons, why do I toss this out for consideration now? Because it would take a year to get this together; for the intra-theatre conversations to begin and bear fruit; for a national sponsor or two to be signed up; for a single advertising campaign to be developed for use by all participants; to insure that a year from now, this grand idea could be unveiled to the public.

Collectively, the number of people who attend theatre on a daily basis in America is significant, but because it’s mostly happening in theatres of perhaps 500 seats or less, its hard for the country at large to get a handle on our significance. So let’s all hang together, since hanging separately doesn’t get us the impact we so desire, so need and so deeply deserve.

Now to find “the” play…

March 19th, 2013 § § permalink

With U.S. theatre seasons being announced almost daily, things have been pretty lively around the old Twitter water cooler, with each successive announcement being immediately met with assessments at every level. How many female playwrights or directors? Is there a range of race and ethnicity among the artists? Is the season safe and predictable or adventurous and enticing? How many new plays, or actual premieres? How many dead writers? How many American playwrights? Any new musicals? The same old Shakespeare plays?

With U.S. theatre seasons being announced almost daily, things have been pretty lively around the old Twitter water cooler, with each successive announcement being immediately met with assessments at every level. How many female playwrights or directors? Is there a range of race and ethnicity among the artists? Is the season safe and predictable or adventurous and enticing? How many new plays, or actual premieres? How many dead writers? How many American playwrights? Any new musicals? The same old Shakespeare plays?

Thanks to social media, what once might have incited some e-mails and calls among friends in the business is now grist for the national mill, and the conversations swing their focus from city to city as rapidly as a new announcement is made. While some of the critiques may strike a more strident tone than I would personally adopt, I have to say that this is evidence of the developing national theatre conscience, under which news of upcoming work is not merely relayed but considered, from a macro rather than micro viewpoint, and not only by artistic directors at conferences or journalists in major media. People are keeping score.

I find this heartening and useful; last year I wrote a column for The Stage in which I declared my belief that the work on U.S. stages must better reflect U.S. society. But even as I applaud every recounting of a season being graded on a variety of balances (gender, race, vintage, etc.), and hope that it informs not only a national conversation but action and change at the local level, I want to strike a note of caution about one of the criteria being applied, specifically: why are so many theatres doing the same plays?

It’s easy if one lives in a major metropolitan area that’s rich in theatre to wonder why certain plays are receiving 10, 15 even 20 productions in a single season, typically works that have been seen in New York, whether on Broadway or off. We all see the list compiled each fall by TCG and American Theatre magazine; it generates stories about the most popular plays at U.S. theatres and usually mirrors the NYC fare of the past year or two. But at the same time, how many new plays remain unproduced, or receive a premiere and then don’t find their way to other stages? Have U.S. theatres become ever more safe and New York-centric?

What seems like a herd mentality has a more practical basis. It has been some time since plays have toured the country with any regularity (before the current War Horse, the last significant non-musical tour I recall was Roundabout’s Twelve Angry Men); the days when a play would run a season on Broadway and then tour for a year are long over. So while not-for-profit theatres may have been born in part to offer an alternative to commercial fare that was once available throughout the country, the life of plays has fallen almost exclusively to institutional companies.

Those companies tend to be fairly hyperlocal, drawing the majority of their audience from a 30 to 45 mile radius. This holds true even for larger cities, although they may benefit from some portion of a tourist trade. Generally, only “destination theatres” like Oregon Shakespeare Festival or Canada’s Stratford and Shaw Festivals can lay claim to a wider geographic spread. So while our overview of production may be all inclusive, the communities being served are less transient and more insular than that view.

On top of that, we can’t deny that theatre in New York has a range of media platforms which, even in our online era, few other cities can match. Consequently, a success in New York, or merely a New York production, gets a boost in the eyes of all concerned – theatre staffs, freelance artists, funders, audiences. And as a result, companies which are the major – or only – theatre in their community may feel duty bound to offer those “name” works in their seasons, because their audiences may not have any other opportunity to see them and also because their artistic leadership believes in the quality and value of that work. Of course, in some markets, theatres may compete for these “name” works, especially if they’re accompanied by the name Tony or Pulitzer.

This was brought home to me years ago during my time as managing director of Geva Theatre in Rochester NY. Geva was by far the largest theatre in Rochester; its peers were the former Studio Arena Theatre in Buffalo, 60 miles to the west, and Syracuse Stage, some 80 miles to the east. Each city had its own theatrical microclimate, with only the smallest sliver of die-hard theatre fans traveling among all three, an effort hampered by a snowfall season that ran from November to April.

Having come from Connecticut theatre, where a daytrip to New York was commonplace for professionals and audience alike, I wasn’t used to working on “last year’s hits” (though Geva’s seasons were certainly much more varied than that). In Connecticut at that time, doing work recently available in NYC was redundant. Frankly, what had been a source of pride at the places I’d worked had become a sign of elitism in my new setting, and I had to adjust my thinking accordingly – a mindset that has stayed with me as I ventured back into Connecticut and then to Manhattan.

This year, Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop has been one of those frequently produced plays; on the east coast alone I know of productions in Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington DC without even looking at schedules; I could just look at the Amtrak Northeast Corridor schedule for that rundown. Some might call this copycatting, especially after its Broadway run the prior season, but based upon reviews and reports of sales, The Mountaintop has been meaningful at each venue where it has appeared, presumably without overlapping audiences. And on a personal note, I have to say that even in a production compromised by a labor dispute, I found the Philadelphia incarnation to be even more affecting than the Broadway one.

Even as I lobby for artistic directors to be ever more committed to a wide range of essential criteria, I acknowledge the difficulty of their task. Aside from taking into account the questions I highlighted in the first paragraph, they also have to consider issues like budget, educational commitments, work that might prove especially meaningful to their audience or their community. Many have to do that with only five or six shows in a given season and it may not be possible to hit every desired mark.

A national survey across a range of criteria will certainly show us trends in production at the country’s institutional theatres, and I avidly support such an effort. But as we look theatre by theatre, we might allow, slightly, for what else could be happening at other theatres in the same city, and perhaps for how each theatre’s season does (or doesn’t) make improvements in diversity year over year. We also have to accept that in meeting one of many goals, a theatre might fall short on another; watching how they trend over time will be the most telling indicator. And while we need more and more platforms for truly new work, if a show with a New York imprimatur is a genuine part of a season striving towards meeting a range of goals, it is not necessarily a cop-out.

A final word for the theatres that face this new scrutiny, from playwright Stephen Spotswood during yesterday’s water cooler chat on Twitter: “Dear theatres whose seasons people are complaining about: This means we care and are invested in you. Start worrying when we stop.”

March 6th, 2013 § § permalink

“There is nothing quite as wonderful as money! There is nothing quite as beautiful as cash!”

I have made no secret of my disdain for the practice of announcing theatre grosses as if we were the movie industry. I grudgingly accept that on Broadway, it is a measure of a production’s health in the commercial marketplace, and a message to current and future investors. But no matter where they’re reported, I feel that grosses now overshadow critical or even popular opinion within different audience segments. A review runs but once, an outlet rarely does more than one feature piece; reports on weekly grosses can become weekly indicators that stretch on for years. If the grosses are an arbiter of what people choose to see, then theatre has jumped the marketing shark.

So it took only one tweet to get me back on my high horse yesterday. A major reporter in a large city (not New York), admirably beating the drum for a company in his area, announced on Twitter that, “[Play] is officially best-selling show in [theatre’s] history.” When I inquired as to whether that meant highest revenue or most tickets sold, the reporter said that is was highest gross, that they had reused the theatre’s own language, and that they would find out about the actual ticket numbers.” I have not yet seen a follow up, but Twitter can be funny that way.

As the weekly missives about box office records from Broadway prove, we are in an endless cycle of ever-higher grosses, thanks to steady price increases, and ever newer records. That does not necessarily mean that more people are seeing shows; in some cases, the higher revenues are often accompanied by a declining number of patrons. Simply put, even though fewer people may be paying more, the impression given is of overall health.

I’m particular troubled when not-for-profits fall prey to this mentality as part of the their press effort, and I think it’s a slippery slope. If not-for-profits are meant to serve their community, wouldn’t a truer picture of their success be how many patrons they serve? In fact, I’d be delighted to see arts organizations announcing that their attendance increased at a faster pace than their box office revenue, meaning that their work is becoming more accessible to more people, even if the shift is only marginal. If selling 500 tickets at $10 each to a youth organization drags down a production’s grosses, that’s good news, and should be framed as such, unless our commitment to the next generation of arts attendees is merely lip service.

From my earliest days in this business, I have advocated for not-for-profit arts groups to be recognized not only as artistic institutions, but local businesses as well. While I think that has come into sharper focus over the past 30 years, I’m concerned that the wrong metrics are being applied, largely in an effort to mirror the yardstick used for movies. It’s worth noting that for music sales or book sales, it’s the number of units sold, not the actual revenue, that is the primary indicator of success, at either the retail or wholesale level (although more sophisticated reporting methods are coming into play).

In a recent New York Times story about a drop in prices at the Metropolitan Opera, I was startled by the assertion that grosses were down in part because donor support for rush tickets had been reduced. Does that mean that fewer tickets were being offered because there wasn’t underwriting for the difference in price? Does it mean that the donor support was actually being recognized as ticket revenue, instead of contributed income? What does it mean for the future of the rush program if the money isn’t replaced – less low-price access? No matter how you slice it, something is amiss.

That said, the Met Opera example brings out an aspect of not-for-profit success that is, to my eyes, less reported upon, namely contributed revenue. Yes, we see stories when a group gets a $1 million gift (in larger cities, the threshold may be higher for media attention). But we don’t get updates on better indicators of a company’s success: the number of individual donors, for example, showing how many people are committing personal funds to a group. The aggregate dollar figure will come out in an annual report or tax filing, but is breadth of support ever trumpeted by organizations or featured in the media? I think it should be. I also can’t help but wonder whether proclaiming high dollar grosses repeatedly might serve to suppress small donations.

Not-for-profit arts organizations exist in order to pursue creative endeavors at least in part in a manner different from the commercial marketplace. Make no mistake, the effort to generate ticket sales for a NFP is equivalent to that of a commercial production, but the art on offer is (hopefully) not predicated on reaching the largest audience possible for the longest period possible. When NFP’s proclaim box office sales records, they are adopting a wholly commercial mindset. While it may appeal to the media, because it aligns with other reportage of other similar fields, it disrupts the perception of the company and their mission. And look out when grosses drop, as they inevitably will at some point.

We all love a hit, whether it’s the high school talent show or a new ballet. But if all we can use to demonstrate our achievements is how big a pile of money we’ve made, well then forgive me if I’m a bit grossed out.

March 5th, 2013 § § permalink

As I said in Part 1 of this series, Matt Trueman’s piece for the Financial Times got me thinking about a variety of issues relating to the exchange of new plays between England and the United States. After focusing on perceived favoritism or bias, and then the common issue of support beyond the box office and its apparent impact on new work, let me circle back to focus more directly on the original issue.

I agree with Trueman, and the people with whom he spoke, that despite a handful of big name plays traversing the pond every year, each country only scratches the surface of the vast number of plays produced by the other. Now, unencumbered as I am by more comprehensive data, what could be the causes for this?

Personally, I don’t really hold with the idea that some of the plays are mired in cultural differences not readily understood. I have certainly seen plays in which cricket plays a role (I don’t understand anything connected with cricket), but the plays aren’t about cricket, and the minutiae of the game is typically irrelevant. We may mention footlong sandwiches in a play, calling them subs, grinders or hoagies, but so long as it’s clear its an item of food, either from other dialogue or stage action, I don’t think English theatergoers would be lost in incomprehension. We may not know the particulars of the National Health Service, or the English may not understand the nuances of city, county, state and national government here, but those are mechanics, not meaning. If we can find common ground in Monty Python and Downton Abbey, I have no worries about plays – even those that require specific regional accents.

I certainly think familiarity and awareness plays a role, and it amplifies a frequent intra-country challenge: if a play is produced in a regional theatre outside of a major media area, how does it get noticed? I don’t doubt that large theatres in both countries have the means and the inclination to look beyond New York and London alone, but how do they look? Literary offices are likely stocked with unread homegrown material, even if they only accept work by agent submission. Media websites may offer reviews of work, but who has the time to scan it all on a daily basis, hunting for a lesser known but worthwhile work. If a play doesn’t get published, or added to the catalogue of a major licensing house, how does it get attention, at home or abroad? Some may like to decry the influence of reviews, but good reviews distributed by theatre or producer may have the most impact, but is there a readily accessible list of artistic directors and literary managers in both countries (and other English-speaking countries) to make the dissemination of that material efficient? To be interested in a play, one first has to hear or read about it.

But let me come back to “homegrown.” In America, we constantly see mission statements that, rightly, talk about theatres serving their community. This can take many forms and be interpreted in a variety of ways, but the fact is that even those not-for-profit companies which also speak of adding to the national and even international theatrical repertoire must first and foremost serve their immediate community, the audience located in a 30 mile radius of their venue, give or take. Many theatres are also making an increased effort to serve the artists in their local community as well, instead of importing talent from one of the coasts. I have no reason to suspect that it is any different in England.

So the question about producing plays from other countries is less one of interest than adherence to mission. If your theatre is the only one of any scale for 30 miles, or the largest even in a crowded field, where should your focus be? Unless your company is specifically dedicated to work from other countries, on balance it’s going to be wise to focus on homegrown plays, especially if your company does new work.

Several months back, the artistic director of a large U.S. theatre and I were discussing a British playwright we both hold in high regard, but the A.D. said he couldn’t make room for that author’s work in a season, even for a U.S. premiere. “If I do that, that’s one less slot I have for a new American play.” With most theatres having perhaps four to seven shows a season, not all necessarily new, it is in fact a tricky political prospect to debut or produce foreign work. Look at the flack Joe Dowling took for his season of Christopher Hampton plays at The Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis.

Add to that the necessity of balancing a season for gender and race, plus the desire to show the audience work that may have debuted elsewhere in the U.S., as well as classics and the challenge grows greater for foreign work (though it doesn’t justify our significant blind spot towards our neighbor Canada or the limited awareness of theater from Australia and New Zealand either). I suspect this comes into play in England as well, but I’d need to speak with more English A.D.’s to know.

When I surveyed the Tony nominations it was quickly apparent that if one removed David Hare, Tom Stoppard, Martin McDonagh, Brian Friel and Yasmina Reza, foreign presence on Broadway would drop precipitously; the same would happen at the Oliviers if one excluded Tony Kushner, August Wilson, and David Mamet. Yes, England has premiered work by Katori Hall, Bruce Norris and Tarrell Alvin McCraney, but they are exceptions to the rule, not exemplars of a new trend.

I support the exchange of dramatic literature and artists between countries – all countries –not just the U.S.-English traffic that has been the focus here. Improved communication about that work might help to foster an increase and, as I said originally, a survey of past productions on a larger scale might reveal more than we’re aware of. But when it comes right down to it, English theatres and artistic directors must focus on what’s most important for their audiences, and American theatres and A.D.s must do the same. What that yields in terms of exchange is simply part of balancing so many necessary elements, tastes, styles and budgets; trends may appear when looking from a distance, but up close, it’s a theatre by theatre function.

March 5th, 2013 § § permalink

In the process of debunking the idea that English and American plays experience bias, for or against them , when produced in the their “opposite” theatrical cities of New York and London, I began to notice something extremely interesting about the origin of plays nominated for the Olivier and Tony Awards. Thinking it might be my own bias coming into play as I assembled data, I expanded my charts of nominated plays beyond simply the country of origin for the works, adding the theatres where the plays originated. What I found suggests that the manner of theatrical production in the two countries may be even more alike than many of us realize.

In the U.S., of the 132 plays nominated for the Tony Award for Best Play between 1980 and 2012, 61 of them had begun in not-for-profit theatres in New York and around the country. That’s 46% of the plays (and even more specifically, their productions) having been initiated by non-commercial venues. In England, 99 of the plays came from subsidised companies, a total of 75% of all of the Oliviers nominees.

Together, these numbers make a striking argument for how essential not-for-profit/subsidized companies are to the theatrical ecology of today. And, frankly, my numbers are probably low.

To work out these figures, I identified plays and productions which originated at not-for-profits. That is to say, if a play was originally produced in a not-for-profit setting, but the production that played Broadway was wholly or significantly new, it was not included. As a result, for example, both parts of Angels in America don’t appear in my calculations, because the Broadway production wasn’t a direct transfer from a not-for-profit, even though its development and original productions had been in subsidized companies in both the U.S. and England.

These statistics also don’t include plays that may have been originally produced in their country of origin at an institutional company, but were subsequently seen across the Atlantic under commercial aegis. So while Douglas Carter Beane’s The Little Dog Laughed is credited with NFP roots in the U.S. it has been treated as commercial in London. Regretfully, I don’t know enough about the origin of all nominated West End productions in companies from outside London to have represented them more fully, which is why I have an inkling that the 75% number is low.

Additionally, it’s worth noting that in England, the Oliviers encompass a number of theatres that are wholly within subsidized companies, in some cases relatively small ones, which needn’t transfer to a conventional West End berth to be eligible; examples include the Royal Court and the Donmar Warehouse, as well as Royal Shakespeare Company productions that visit London. While there are currently five stages under not for profit management on Broadway (the Sondheim, American Airlines, Beaumont, Friedman Theatres and Studio 54), imagine if work at such comparable spaces as the Mitzi Newhouse, the Laura Pels, The Public, The Atlantic and Signature were eligible as well.

Why am I so quickly demonstrating the flaws in my method? Simply to show that even by conservative measure, it is the institutional companies, which rely on grants, donations and government support to function, which are producing the majority of the plays deemed to be the most important of those that play the major venues in each city.

Since we must constantly make the case for the value of institutional, not-for-profit, subsidized theatre, in the U.S. and in England (let alone Scotland, Ireland, Canada and so many other countries), I say tear apart my process and build your own, locally, regional and certainly nationally. I think you’ll find your numbers to be even stronger than mine and, hopefully, even more persuasive. While it may seem counterintuitive for companies outside London and New York to use those cities’ awards processes to make their case, the influence is undeniable.

March 5th, 2013 § § permalink

The conventional wisdom in theatrical circles is that America is stunningly Anglophilic, that we readily embrace works from England on our stages. Supposedly we do this to the detriment of American writers, and our affection is reputedly one-sided, as the British pay much less attention to our work. So they say.

This past weekend, British arts journalist Matt Trueman began a worthwhile conversation in an article for the Financial Times, in which he suggested that most American plays rarely reach England, and vice-versa. While a few of the assertions in the piece may not be wholly accurate, I think the central argument holds true: only a handful of plays from each country get significant exposure in the other. His piece set me thinking.

Much of America’s vision of British theatre is dominated by the fare on Broadway and, I suspect, it’s the same case in the West End for America. Now we can argue that these two theatrical centers don’t accurately represent the totality or even the majority of theatre in each country (and I have done so), but the high exposure in these arenas does have a significant impact on the profile and life-span of new plays, fairly or not. Consequently, our view of the dramatic repertoire from each country to the other is a result of a relative handful of productions in very specific circumstances.

Given the resources and data, one could perhaps build a database of play production in both countries and extract the most accurate picture. But in an effort to work with a manageable data set in exploring this issue, I took the admittedly subjective universe of the Best New Play nominations for the Tony and Olivier Awards, from 1980 to today. While significantly more work is produced than is nominated, this universe at least afforded me the opportunity to examine whether there is cultural bias among select theatrical arbiters. Although each has its own rules and methodology (I explain key variables in my addendum below), they are a microcosm of top-flight production in these “theatre capitals.”

So as not to keep you in suspense, here’s the gist: new English and American plays are nominated for Tony and Oliviers at roughly the same rate in the opposite country, running between 20 and 25% of the nominees when produced overseas.

In the past 33 years of Tony Awards, 32 English plays were nominated for Tonys out of a universe of 132, or 24% of the total. At the Oliviers, 20% of the Best New Play nominees were American. In my eyes, that 4% difference is irrelevant; though there’s no margin for error since this isn’t a poll, the total numbers worked with are small enough so that a few points means only a few plays, in this case, only five.

Now, let’s take a step back and look at this with larger world view. While Americans at large may have a tendency to blur distinctions between English, Welsh, Irish and Scottish, I’m aware that these national distinctions are extremely important. Blending these countries in our view of theatrical production may be contributing to the false American perception of English imperialism on our stages.

Factoring in all productions by foreign authors (the aforementioned Ireland, Wales and Scotland, as well as France, Canada, Israel and South Africa), we find that 44 plays from outside the U.S. received Tony nominations in 33 years, for 33% of the total nominees, while in England, foreign plays garnered 52 Olivier nods, for 39% of the total. So while the gap here is slightly wider, it shows that English plays actually are nominated less in their own country than American plays are at the Oliviers.

When it comes to the recognition of plays that travel between these two major theatrical ports of call, I think it’s fair to say that, so far as each city’s major theatrical award is concerned, there is no bias, no favoritism. Even if the number of plays being produced are out of balance, the recognition is proportional. Perhaps we can put that old saw to rest.

P.S. For those of you feeling petty, wondering whether there’s an imbalance in winners? American plays have won the Olivier nine times since 1980, while English authors have won the Best Play Tony seven times. So there.

* * * * *

Notes on methodology:

- Musicals were not studied, only plays.

- There is one key difference between the Best Play categories at the Tonys and The Oliviers, specifically that the Oliviers also have a category for Best Comedy in many of the years studied. While it is not included in this comparison, it should be noted that, with a few exceptions, American plays were rarely nominated in the Best Comedy category. Whether this is a result of U.S. comedies not traveling to England at all, or cultural differences causing U.S. comedies to be poorly received when they did travel, was not examined.

- To some degree, nationality or origin of the plays required a judgment call. There are Americans who have resided in England for many years (Martin Sherman, Timberlake Wertenbaker), in addition to authors of South African and Irish birth who also make their home there (Nicholas Wright, Martin McDonagh). I have categorized these authors and their plays by the country with which they are most associated, as I do not have access to their citizenship records. In all cases, I have identified nationality to the best of my ability.

As I’ve written in the past, what happens in New York theatre is a superb predictor of what will happen in regional theatre in the coming seasons, especially when it comes to plays. Any play that makes it to Broadway, or gets a great New York Times review, is going to grab the attention of regional producers. Throw in Tony nominations, let alone a Tony win – or the Pulitzer – and those are the plays that will quickly crop up on regional theatre schedules.

As I’ve written in the past, what happens in New York theatre is a superb predictor of what will happen in regional theatre in the coming seasons, especially when it comes to plays. Any play that makes it to Broadway, or gets a great New York Times review, is going to grab the attention of regional producers. Throw in Tony nominations, let alone a Tony win – or the Pulitzer – and those are the plays that will quickly crop up on regional theatre schedules. Perhaps this rush to the familiar and popular and NYC-annointed is disheartening, but it’s worth observing that the American Theatre list notes how many productions each title gets, and that after the first couple of slots, we’re usually looking at plays that are getting 7 or 8 productions in a given season, across TCG’s current universe of 474 member companies (404 of which were included in this year’s figures). Since the magazine notes a universe of 1,876 productions, suddenly 27 stagings of a single show doesn’t seem so dominant after all. Granted, TCG drops Shakespeare from their calculations, but even he only counted for 77 productions of all of his plays across this field. So reading between the lines, the American Theatre list suggests there’s very little unanimity about what’s done at TCG member theatres in any given year, a less quantifiable achievement but an important one.

Perhaps this rush to the familiar and popular and NYC-annointed is disheartening, but it’s worth observing that the American Theatre list notes how many productions each title gets, and that after the first couple of slots, we’re usually looking at plays that are getting 7 or 8 productions in a given season, across TCG’s current universe of 474 member companies (404 of which were included in this year’s figures). Since the magazine notes a universe of 1,876 productions, suddenly 27 stagings of a single show doesn’t seem so dominant after all. Granted, TCG drops Shakespeare from their calculations, but even he only counted for 77 productions of all of his plays across this field. So reading between the lines, the American Theatre list suggests there’s very little unanimity about what’s done at TCG member theatres in any given year, a less quantifiable achievement but an important one. While titles come and go on the American Theatre list, stasis is the best word to describe the lists of most produced high school plays (it’s somewhat less true for musicals). Nine of the plays on the 2014 list were on the 2013 list; 2014 was topped by John Cariani’s Almost, Maine, followed by A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the two titles were in reverse order the prior year. The other duplicated titles were Our Town, 12 Angry Men (Jurors), You Can’t Take It With You, Romeo and Juliet, The Crucible, Harvey and The Importance of Being Earnest.

While titles come and go on the American Theatre list, stasis is the best word to describe the lists of most produced high school plays (it’s somewhat less true for musicals). Nine of the plays on the 2014 list were on the 2013 list; 2014 was topped by John Cariani’s Almost, Maine, followed by A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the two titles were in reverse order the prior year. The other duplicated titles were Our Town, 12 Angry Men (Jurors), You Can’t Take It With You, Romeo and Juliet, The Crucible, Harvey and The Importance of Being Earnest. Almost, Maine’s swift ascension to the top rungs of the list is extraordinary, but it’s due in no small part to its construction as a series of thematically linked scenes, originally played by just four actors but easily expandable for casts where actor salaries aren’t an issue. Looking at recent American Theatre lists, they tend to be topped by plays with small casts (Venus in Fur, Red, Good People and The 39 Steps), while the Dramatics list is the reverse, with larger cast plays dominating, in order to be inclusive of more students (though paling next to musicals where casts in school shows might expand to 50 or more).

Almost, Maine’s swift ascension to the top rungs of the list is extraordinary, but it’s due in no small part to its construction as a series of thematically linked scenes, originally played by just four actors but easily expandable for casts where actor salaries aren’t an issue. Looking at recent American Theatre lists, they tend to be topped by plays with small casts (Venus in Fur, Red, Good People and The 39 Steps), while the Dramatics list is the reverse, with larger cast plays dominating, in order to be inclusive of more students (though paling next to musicals where casts in school shows might expand to 50 or more). Musicals are of course a staple of high school theatre, but the top ten lists from Dramatics are somewhat more fluid. While staples like Guys and Dolls, Grease, Once Upon a Mattress, You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown and Little Shop of Horrors maintain their presence, newer musicals arrive every year or two, with works like Seussical, Legally Blonde, Spelling Bee, and Thoroughly Modern Millie appearing frequently in recent years. At the peak spot, after a six-year run, Beauty and the Beast was bested this year by Shrek; as with professional companies, when popular new works are released into the market, they quickly rise to the top. How long they’ll stay is anyone’s guess, but I have little doubt that we’ll one day see Aladdin and Wicked settle in for long tenures.

Musicals are of course a staple of high school theatre, but the top ten lists from Dramatics are somewhat more fluid. While staples like Guys and Dolls, Grease, Once Upon a Mattress, You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown and Little Shop of Horrors maintain their presence, newer musicals arrive every year or two, with works like Seussical, Legally Blonde, Spelling Bee, and Thoroughly Modern Millie appearing frequently in recent years. At the peak spot, after a six-year run, Beauty and the Beast was bested this year by Shrek; as with professional companies, when popular new works are released into the market, they quickly rise to the top. How long they’ll stay is anyone’s guess, but I have little doubt that we’ll one day see Aladdin and Wicked settle in for long tenures.