April 25th, 2016 § § permalink

This morning, I was both annoyed and bemused to learn that Mark Rylance and Derek Jacobi, two esteemed British actors, had just been given airtime by National Public Radio, to advance the Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare’s true identity. This minority opinion about the authorship of the canon of works credited to Shakespeare holds that a commoner like Shakespeare couldn’t have possibly written the plays, and typically credits a British nobleman with having written them secretly. There’s a strong whiff of classism in the position, positing that genius can’t come from humble beginnings. But Rylance and Jacobi’s conspiracy theories on this subject are nothing new, and while I have to wonder at NPR’s decision to advance the theory without presenting any countervailing positions, at least they had the courtesy to wait until this weekend’s Shakespeare 400 anniversary and celebrations had passed.

As it turns out, this morning in England, The Telegraph gave another major British actor the opportunity to hold forth on another subject steeped in history. Simon Callow, who I have interviewed (and chatted with casually once, unexpectedly, on the tube), has announced that he doesn’t see what’s wrong with “blacking up,” an old theatre tradition. You say you don’t know the term? Well in America, it’s called blackface, and is widely held to be offensive, insensitive and wholly out of step with modern practice.

Starting with his opposition to the idea that transgender actors should have precedence in the casting of transgender roles, Callow moves on takes the standard argument against culturally specific casting, pursuing it to ridiculous ends. Quoting him, from The Telegraph:

“This is madness. The whole idea of acting has gone out of the window, if you follow the logic of that,” he says.

“To say it is offensive to transgendered people for non-trans people to play them is nonsense. Because you have to have been a murderer to play Macbeth, you have to be Jewish to play Shylock. It’s nonsense.

“The great point of acting is that it is an act of empathy about someone you don’t know or understand. I continue to defend Laurence Olivier’s performance as Othello.”

Later in the article, the following appears:

I ask if he’d ever consider playing Othello, even though blacking up is widely considered offensive. “Is it so offensive? I don’t know. People say it’s offensive because it reminds you of the Black & White Minstrel show. But, it’s a different thing altogether.”

He adds: “It would depend on the circumstances, absolutely. But, there is actually ban on it in my union. You can not do it. You can not black up,” he says this in a way that suggests he does not wholly approve.

Equity, the actors’ union, in fact has no veto. A spokesman says, “we don’t have the power to ban”, but does make clear that “we are absolutely opposed to blacking up” except in “very exceptional circumstances”.

Callow does contradict himself on the subject:

“I totally accept it was the right thing to do to put a moratorium on white actors playing Othello, to allow black actors to fill those giant boots.” However, he then adds: “I can not say that the principle is a correct one.”

It is impossible to know whether Callow’s opinion lurks in the psyches of other British actors of his generation, or whether he’s an outlier (the author of the article does conclude by slyly cautioning Callow away from playing Othello). His comparison of blackface to Robert de Niro gaining weight for Raging Bull borders on the absurd. But the fact remains that he is respected not only as an actor but as a historian (his multi-volume biography of Orson Welles, with three completed and one to go is an impressive work of scholarship).

Consequently, when Callow speaks, he generates headlines, and his position, while acknowledging the prevailing sentiment, advocates for and gives credence to sustaining a practice that is decried by artists of color and their allies, be it blacking up or being “yellowed-up,” as The Telegraph refers to Jonathan Pryce’s performance in Miss Saigon. That Callow, one of the first British actors to come out as gay, finds prioritizing transgender actors for transgender roles to be so much “nonsense” works against the efforts of the transgender creative community, though surely it offers Eddie Redmayne some comfort.

Is this “an English thing,” a difference between American and British racial, gender and cultural sensibilities? Certainly the outcry over the yellowface The Orphan of Zhao at the Royal Shakespeare Company several years ago would suggest that the two nations are fairly close on their evolution towards cultural sensitivity, with both missteps and voices ready to speak against them. I write that as someone who still sees reports of yellowface and brownface with some regularity in the U.S., as well as redface (looking at you, Wooster Group). How the performing arts welcome transgender actors in transgender roles is still evolving, but rapidly, and in the direction of authenticity in casting.

What I don’t see in the U.S. is a famous actor in a major media outlet yearning for a return to the time when Caucasians played black, Latino, Asian, Native American and other characters of color with impunity; I don’t see actors denying the legitimacy of the positions of their trans* colleagues. The voices supporting such positions in the U.S. tend to turn up in social media feeds and comments sections, often with fictitious names. I trust the UK advocacy organization Act For Change will be responding to Callow very soon.

“Is blacking up offensive survey,” as of April 25, 7 pm

In the meantime, Callow’s statements are a reminder that the idea and ideal of cultural diversity in the arts is still fighting an uphill battle, as evidenced by The Telegraph’s own online survey, embedded in the Callow story, which determined that 77% of their readers do not find blacking up to be offensive. Remarks like these must be challenged by diversity advocates, strongly, wherever they appear. If I happen to run into Callow again, I’ll be tempted to quote myself on this subject, though I need to expand my full statement, which spoke first and foremost to race, to embrace transgender actors as well:

The whole point of diversifying our theatre is not to give white artists yet more opportunities, but to try to address the systemic imbalance, and indeed exclusion, that artists of color, artists with disabilities and even non-male artists have experienced. Of course, when it comes to roles specifically written for POC, those roles should be played by actors of that race or ethnicity – and again, not reducing it to the level of only Italians should play Italians and only Jews should plays Jews, but that no one should be painting their faces to pretend to an ethnicity which is obviously not theirs, while denying that opportunity to people of that race.

In the meantime, perhaps Callow will get off the casting soapbox and throw in his lot with the Oxfordians, if he desires to publicly take on unpopular positions. I’m sure the late 17th Earl of Oxford will be delighted with the effort.

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts.

March 9th, 2016 § § permalink

Avenue Q at Warsaw Federal Incline Theater (Photo by Jennifer Perrino)

“In America, where we have diverse populations, even if you’re in a community theatre, I think it’s better to not do the show rather than do it in yellowface or blackface.”

“The show” in question is Avenue Q, the 2004 Tony Award winning send-up of Sesame Street. The speaker is Robert Lopez, the co-conceiver, co-composer and co-lyricist (with Jeff Marx) of the musical; Lopez is also an award recipient for his work on Broadway’s The Book of Mormon and Disney’s film Frozen. Lopez was responding to questions provoked by a recent article in the Cincinnati Enquirer by David Lyman, a freelance writer covering arts and culture for the paper, entitled “Yellowface: The New Blackface?” Lyman’s article was instigated by the casting of the role of Japanese immigrant Christmas Eve in the Warsaw Federal Incline Theater production of Avenue Q, which closed this past weekend.

“The show” in question is Avenue Q, the 2004 Tony Award winning send-up of Sesame Street. The speaker is Robert Lopez, the co-conceiver, co-composer and co-lyricist (with Jeff Marx) of the musical; Lopez is also an award recipient for his work on Broadway’s The Book of Mormon and Disney’s film Frozen. Lopez was responding to questions provoked by a recent article in the Cincinnati Enquirer by David Lyman, a freelance writer covering arts and culture for the paper, entitled “Yellowface: The New Blackface?” Lyman’s article was instigated by the casting of the role of Japanese immigrant Christmas Eve in the Warsaw Federal Incline Theater production of Avenue Q, which closed this past weekend.

In the piece, Lyman wrote, “It probably shouldn’t have surprised me when I saw the Warsaw Federal Incline Theater’s production of Avenue Q and found the character of Christmas Eve – “I am Japanese,” she declares at one point – played by an actress who looked white. (More on this later.) Showbiz Players did the same thing when it produced the show in 2012.” Lyman went on to write, “While casting an ethnically appropriate Asian actor may be more difficult in Greater Cincinnati than in Seattle, it is not impossible.”

Lyman was prompted to examine Avenue Q due to a Facebook colloquy begun by Cincinnati actress Elizabeth Molloy on February 7, ten days before the production began its run. It began:

How is it 2016, and I still have to explain to people that yellowface is wrong?

I mean, everyone knows that blackface is a no-no, right? (RIGHT?!). So why is it so difficult to extend that same logic to other races? Do I really have to point out that yellowface is just as terrible, just as insulting, just as disrespectful, and just as mean as blackface?

In an interview, Lyman said he did not know Molloy well, but saw her remarks because mutual friends shared them on Facebook. Lyman said that as a freelancer, he does not review every show in the area. “This [Avenue Q] was one I probably was not going to see,” he notes, but as a result of Molloy’s post, “I thought, ‘Well OK, I need to change my plans and I did.” Lyman notes that he paid for his seat.

In his article, Lyman wrote:

So is it essential that an actor look Asian? Or is it enough that a person’s heritage somehow reflect an Asian heritage? [The actress] doesn’t look particularly Asian. But according to Rodger Pille, director of communications and development for Cincinnati Landmark Productions, the Incline’s parent organization, [the actress] said that her great-great-great-grandmother was Ma’ohi, from the island of Tahiti.

“Once we knew that she did have some of that descent, we felt we could move forward with the casting,” says Pille. “That was enough for us. We didn’t want to be the arbiter of what percentage Asian she was.”

He has a point. Theaters shouldn’t have to check genetic code before they allow a person to audition for a particular role. But they should be sensitive and use common sense.

Please note that the name of the actor has been omitted above, and will not figure in this article. The responsibility for the casting lies with the theatre and production’s director. The goal here is to explore the ramifications of the casting in Cincinnati, not to in any way shame a performer who had a chance for paid work in what is surely a limited range of opportunities in the city. Warsaw Federal Incline Theater is a professional non-Equity company, described by several people as the top non-Equity theatre in the area, with sufficient influence that several individuals contacted for this article declined to be interviewed out of concern for alienating the leadership of the company.

As Lyman’s article spread nationally, it reached Erin Quill, a staunch advocate for authenticity in racial casting and, as it happens, the original understudy for the role of Christmas Eve in the Broadway company of Avenue Q. She has written her own commentary about the situation on her blog, “The Fairy Princess Diaries,” but also responded to questions resulting from Lyman’s article via e-mail. She wrote:

CE [Christmas Eve] is an immigrant from Japan. First generation. There is an obligation to showcase the character in such a way that honors the writers’ intentions. CE is Japanese. It is in the script.

I think it is fair to say that in this particular case, with a reviewer being so distracted by concerns of ‘whitewashing’ while he viewed the show in Cincinnati that he felt he had to write extensively about it – I think the Creative/Production Team did not do their job. They may be good people, but good people make bad decisions all the time.

Actors don’t cast themselves. As Ann Harada tweeted me the other day ‘Sometimes people need time for learning’ – and this is really what it is –learning where the line is drawn for an audience to buy into the show. According to that review –this casting is problematic. I for one, am glad that diversity is being discussed in Cincinnati theater, I hope it continues.

Quill went on to write,:

I believe that as we are now 15 years (gulp) down the road- you can always find a person to play the role that would be appropriate. You cannot sell me on the idea that ‘no one came in’ – and if that IS the rare instance – make a phone call and see who is out there that is available.

Saying ‘we could not find any’ is laziness.

Ann Harada, referred to by Quill, originated the role of Christmas Eve, in workshop, Off-Broadway at The Vineyard Theatre and on Broadway. Regarding the Warsaw Federal Incline production she wrote via e-mail:

I do understand the limitations of casting certain roles, but then, why do the play? I have a hard time believing they’d use a White Othello instead of just not doing Othello. That being said, I always wish I’d seen the international productions of Q like in Denmark, God knows who played Christmas Eve and Gary [Coleman] in that one.

I’ve met a few white Christmas Eves in my time, mostly adorable young girls who played her in high school. Whatever. Which is why we can’t get upset at the actress who was cast, it’s not her fault. It’s interesting and a little hurtful that her heritage was deemed “exotic” enough to pass for Japanese but ultimately it is a decision we have to lay at the feet of the producers and creative team.

In response to whether the character of Christmas Eve, with her heavily accented English, could be perceived as a stereotype, Harada wrote:

I was concerned that the role would be viewed as a stereotype but I felt it was integral to the points made in the show that the character have an accent. I know several people who expressed their dismay to me about the accent and my response was ” you don’t get it”. If I felt Christmas Eve was a stereotypical character (submissive, shy lotus blossom, good at math, that sort of thing) it might be one thing but she was so obviously tough, smart, educated and aggressive that I felt she was a fully rounded person. People do have accents. It doesn’t make them less smart or interesting or valid than people who don’t have accents.

Except for a few specific lines, the script of Avenue Q does not write in an accent or dialect for Christmas Eve. While it does drop articles and reverse pluralization of words, lines like “Ev’lyone’s a ritter bit lacist” are the exception in the text, rather than the rule. That was very intentional, said Lopez, though he warned of overdoing it. Lopez, incidentally, describes himself as “half Filipino, half a medley of Irish, English, Canadian, Latvian and other stuff.”

“I think that’s the way the performer would prefer to read the script, so that’s how we presented it,” Lopez explained. “I think there’s a description that says she speaks with a heavy accent and that’s not something that we’re trying to micromanage exactly. It’s on a performer by performer basis. I’ve seen it done even by professionals and it’s made me uncomfortable and I always give a note about it. Because there’s a line – and it’s not just a racial sensitivity thing, it’s a comedy sensitivity thing. If you play something cheap, if you play it for cheap laughs, instead of playing the truth behind it, it will always be offensive. Bad comedy always offends me in all forms. Avenue Q has that pitfall because it’s puppets. In many ways it’s cartoony, but on the other hand it’s also real, it’s also about real life. Unless the actors play the truth of the characters, the show is just a shadow of itself.”

It’s worth noting that among its various transgressive elements, which includes a gender switch in casting which calls for a actress to play the role of Gary Coleman, early workshop iterations, including its five performances at the O’Neill Theater Center in Connecticut, saw a white actress in that role. Lopez said that the original intent was meant to be merely another example of the show’s irreverence. He credits the show’s commercial producers with prompting Lopez, Whitty, Marx and director Jason Moore to cast a black actress when the show moved to full production. Lopez said he would not support a return to the casting of a white actress in that role. [In full disclosure, at the time of the 2002 workshop, I was executive director of The O’Neill Center, and while I found the casting choice very strange when I learned of it, I did not make any objection to it. In the same situation today, I would let my voice be heard speaking against the choice.]

This past Sunday, during a Democratic presidential debate, CNN moderator Don Lemon cited the Avenue Q song “Everyone’s A Little Bit Racist,” which indicated that 13 years after its Broadway debut, the show’s messages remain current.

“Sometimes I wondered about that song and sometimes I think that people don’t get the spirit in which it’s meant,” said Lopez. “It’s certainly not intended for us to relax our standards as far as the way we treat other people. The only way we can move forward is if we acknowledge where we are. So the song in that sense is relevant.”

In the wake of his article about the Warsaw Federal Incline production, David Lyman said that while he was surprised to see few responses in the article’s comments section, he had gotten “dozens of communications” in its wake via e-mail and on social media.

Describing the response as “uniformly supportive,” Lyman characterized the messages as saying, “I’m glad you brought this up. It’s about time somebody wrote something like this. I’m impressed. I’m proud of the paper for doing that.” He contrasted this with the responses he received several years ago when he called out a University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music production for using the original script of the musical Peter Pan, complete with archaic representations of Native Americans and still featuring the song “Ugg-a-Wugg.” He said that in his review, he expressed the opinion, “’Well shame on them. They shouldn’t be doing that. This is the wrong century for that.’ That did not go down well. I got a fair amount of negative feedback on that one.”

Lyman also noted that he had not heard anything from the Warsaw Federal Incline Theatre itself since his article came out. For this article, multiple attempts were made, via phone and e-mail, to contact executive and artistic director Tim Perrino as well as communications/development director Rodger Pille, of Cincinnati Landmark Productions, the parent organization behind Warsaw Federal Incline. Neither responded to any of the inquiries. That gives Lopez, Harada, Quill, Lyman and even Elizabeth Molloy, who began the conversation, the final words on the subject, namely that when casting roles where race is specified, the roles should be filled by actors of that race.

But Lopez, in considering the subject of the show’s continued relevance, struck a conciliatory note while making clear what the lessons should be from and for Cincinnati, as well as any future productions of Avenue Q.

“I think that the dialogue has widened,” observed Lopez. “I think people are more comfortable sharing their opinions. I think as the conversation widens to include to everybody’s point of view, we all benefit from learning what offends people and learning what in fact their point of view is. I think we all learn from that, but unless we all talk about it, you don’t learn. In some ways, unless you cast a white Christmas Eve, you don’t learn that that’s wrong, you don’t learn that that’s not OK with people.”

Even though Avenue Q is closed, David Lyman notes that the issue of authenticity in racial casting retains great currency, not only in Cincinnati, but at this particular theatre. “Warsaw Federal incline Theatre is doing Anything Goes in June,” notes Lyman. “What are we going to see there? We’ve got these two Chinese guys. Are they going to make any effort to find Asians? I don’t know. We’re going to find out.”

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

March 9th, 2016 § § permalink

“In America, where we have diverse populations, even if you’re in a community theatre, I think it’s better to not do the show rather than do it in yellowface or blackface.”

“In America, where we have diverse populations, even if you’re in a community theatre, I think it’s better to not do the show rather than do it in yellowface or blackface.”

“The show” in question is Avenue Q, the 2004 Tony Award winning send-up of Sesame Street. The speaker is Robert Lopez, the co-conceiver, co-composer and co-lyricist (with Jeff Marx) of the musical; Lopez is also an award recipient for his work on Broadway’s The Book of Mormon and Disney’s film Frozen. Lopez was responding to questions provoked by a recent article in the Cincinnati Enquirer by David Lyman, a freelance writer covering arts and culture for the paper, entitled “Yellowface: The New Blackface?” Lyman’s article was instigated by the casting of the role of Japanese immigrant Christmas Eve in the Warsaw Federal Incline Theater production of Avenue Q, which closed this past weekend.

In the piece, Lyman wrote, “It probably shouldn’t have surprised me when I saw the Warsaw Federal Incline Theater’s production of Avenue Q and found the character of Christmas Eve – “I am Japanese,” she declares at one point – played by an actress who looked white. (More on this later.) Showbiz Players did the same thing when it produced the show in 2012.” Lyman went on to write, “While casting an ethnically appropriate Asian actor may be more difficult in Greater Cincinnati than in Seattle, it is not impossible.”

Lyman was prompted to examine Avenue Q due to a Facebook colloquy begun by Cincinnati actress Elizabeth Molloy on February 7, ten days before the production began its run. It began:

How is it 2016, and I still have to explain to people that yellowface is wrong?

I mean, everyone knows that blackface is a no-no, right? (RIGHT?!). So why is it so difficult to extend that same logic to other races? Do I really have to point out that yellowface is just as terrible, just as insulting, just as disrespectful, and just as mean as blackface?

In an interview, Lyman said he did not know Molloy well, but saw her remarks because mutual friends shared them on Facebook. Lyman said that as a freelancer, he does not review every show in the area. “This [Avenue Q] was one I probably was not going to see,” he notes, but as a result of Molloy’s post, “I thought, ‘Well OK, I need to change my plans and I did.” Lyman notes that he paid for his seat.

In his article, Lyman wrote:

So is it essential that an actor look Asian? Or is it enough that a person’s heritage somehow reflect an Asian heritage? [The actress] doesn’t look particularly Asian. But according to Rodger Pille, director of communications and development for Cincinnati Landmark Productions, the Incline’s parent organization, [the actress] said that her great-great-great-grandmother was Ma’ohi, from the island of Tahiti.

“Once we knew that she did have some of that descent, we felt we could move forward with the casting,” says Pille. “That was enough for us. We didn’t want to be the arbiter of what percentage Asian she was.”

He has a point. Theaters shouldn’t have to check genetic code before they allow a person to audition for a particular role. But they should be sensitive and use common sense.

Please note that the name of the actor has been omitted above, and will not figure in this article. The responsibility for the casting lies with the theatre and production’s director. The goal here is to explore the ramifications of the casting in Cincinnati, not to in any way shame a performer who had a chance for paid work in what is surely a limited range of opportunities in the city. Warsaw Federal Incline Theater is a professional non-Equity company, described by several people as the top non-Equity theatre in the area, with sufficient influence that several individuals contacted for this article declined to be interviewed out of concern for alienating the leadership of the company.

As Lyman’s article spread nationally, it reached Erin Quill, a staunch advocate for authenticity in racial casting and, as it happens, the original understudy for the role of Christmas Eve in the Broadway company of Avenue Q. She has written her own commentary about the situation on her blog, “The Fairy Princess Diaries,” but also responded to questions resulting from Lyman’s article via e-mail. She wrote:

CE [Christmas Eve] is an immigrant from Japan. First generation. There is an obligation to showcase the character in such a way that honors the writers’ intentions. CE is Japanese. It is in the script.

I think it is fair to say that in this particular case, with a reviewer being so distracted by concerns of ‘whitewashing’ while he viewed the show in Cincinnati that he felt he had to write extensively about it – I think the Creative/Production Team did not do their job. They may be good people, but good people make bad decisions all the time.

Actors don’t cast themselves. As Ann Harada tweeted me the other day ‘Sometimes people need time for learning’ – and this is really what it is –learning where the line is drawn for an audience to buy into the show. According to that review –this casting is problematic. I for one, am glad that diversity is being discussed in Cincinnati theater, I hope it continues.

Quill went on to write,:

I believe that as we are now 15 years (gulp) down the road- you can always find a person to play the role that would be appropriate. You cannot sell me on the idea that ‘no one came in’ – and if that IS the rare instance – make a phone call and see who is out there that is available.

Saying ‘we could not find any’ is laziness.

Ann Harada, referred to by Quill, originated the role of Christmas Eve, in workshop, Off-Broadway at The Vineyard Theatre and on Broadway. Regarding the Warsaw Federal Incline production she wrote via e-mail:

I do understand the limitations of casting certain roles, but then, why do the play? I have a hard time believing they’d use a White Othello instead of just not doing Othello. That being said, I always wish I’d seen the international productions of Q like in Denmark, God knows who played Christmas Eve and Gary [Coleman] in that one.

I’ve met a few white Christmas Eves in my time, mostly adorable young girls who played her in high school. Whatever. Which is why we can’t get upset at the actress who was cast, it’s not her fault. It’s interesting and a little hurtful that her heritage was deemed “exotic” enough to pass for Japanese but ultimately it is a decision we have to lay at the feet of the producers and creative team.

In response to whether the character of Christmas Eve, with her heavily accented English, could be perceived as a stereotype, Harada wrote:

I was concerned that the role would be viewed as a stereotype but I felt it was integral to the points made in the show that the character have an accent. I know several people who expressed their dismay to me about the accent and my response was ” you don’t get it”. If I felt Christmas Eve was a stereotypical character (submissive, shy lotus blossom, good at math, that sort of thing) it might be one thing but she was so obviously tough, smart, educated and aggressive that I felt she was a fully rounded person. People do have accents. It doesn’t make them less smart or interesting or valid than people who don’t have accents.

Except for a few specific lines, the script of Avenue Q does not write in an accent or dialect for Christmas Eve. While it does drop articles and reverse pluralization of words, lines like “Ev’lyone’s a ritter bit lacist” are the exception in the text, rather than the rule. That was very intentional, said Lopez, though he warned of overdoing it. Lopez, incidentally, describes himself as “half Filipino, half a medley of Irish, English, Canadian, Latvian and other stuff.”

“I think that’s the way the performer would prefer to read the script, so that’s how we presented it,” Lopez explained. “I think there’s a description that says she speaks with a heavy accent and that’s not something that we’re trying to micromanage exactly. It’s on a performer by performer basis. I’ve seen it done even by professionals and it’s made me uncomfortable and I always give a note about it. Because there’s a line – and it’s not just a racial sensitivity thing, it’s a comedy sensitivity thing. If you play something cheap, if you play it for cheap laughs, instead of playing the truth behind it, it will always be offensive. Bad comedy always offends me in all forms. Avenue Q has that pitfall because it’s puppets. In many ways it’s cartoony, but on the other hand it’s also real, it’s also about real life. Unless the actors play the truth of the characters, the show is just a shadow of itself.”

It’s worth noting that among its various transgressive elements, which includes a gender switch in casting which calls for a actress to play the role of Gary Coleman, early workshop iterations, including its five performances at the O’Neill Theater Center in Connecticut, saw a white actress in that role. Lopez said that the original intent was meant to be merely another example of the show’s irreverence. He credits the show’s commercial producers with prompting Lopez, Whitty, Marx and director Jason Moore to cast a black actress when the show moved to full production. Lopez said he would not support a return to the casting of a white actress in that role. [In full disclosure, at the time of the 2002 workshop, I was executive director of The O’Neill Center, and while I found the casting choice very strange when I learned of it, I did not make any objection to it. In the same situation today, I would let my voice be heard speaking against the choice.]

This past Sunday, during a Democratic presidential debate, CNN moderator Don Lemon cited the Avenue Q song “Everyone’s A Little Bit Racist,” which indicated that 13 years after its Broadway debut, the show’s messages remain current.

“Sometimes I wondered about that song and sometimes I think that people don’t get the spirit in which it’s meant,” said Lopez. “It’s certainly not intended for us to relax our standards as far as the way we treat other people. The only way we can move forward is if we acknowledge where we are. So the song in that sense is relevant.”

In the wake of his article about the Warsaw Federal Incline production, David Lyman said that while he was surprised to see few responses in the article’s comments section, he had gotten “dozens of communications” in its wake via e-mail and on social media.

Describing the response as “uniformly supportive,” Lyman characterized the messages as saying, “I’m glad you brought this up. It’s about time somebody wrote something like this. I’m impressed. I’m proud of the paper for doing that.” He contrasted this with the responses he received several years ago when he called out a University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music production for using the original script of the musical Peter Pan, complete with archaic representations of Native Americans and still featuring the song “Ugg-a-Wugg.” He said that in his review, he expressed the opinion, “’Well shame on them. They shouldn’t be doing that. This is the wrong century for that.’ That did not go down well. I got a fair amount of negative feedback on that one.”

Lyman also noted that he had not heard anything from the Warsaw Federal Incline Theatre itself since his article came out. For this article, multiple attempts were made, via phone and e-mail, to contact executive and artistic director Tim Perrino as well as communications/development director Rodger Pille, of Cincinnati Landmark Productions, the parent organization behind Warsaw Federal Incline. Neither responded to any of the inquiries. That gives Lopez, Harada, Quill, Lyman and even Elizabeth Molloy, who began the conversation, the final words on the subject, namely that when casting roles where race is specified, the roles should be filled by actors of that race.

But Lopez, in considering the subject of the show’s continued relevance, struck a conciliatory note while making clear what the lessons should be from and for Cincinnati, as well as any future productions of Avenue Q.

“I think that the dialogue has widened,” observed Lopez. “I think people are more comfortable sharing their opinions. I think as the conversation widens to include to everybody’s point of view, we all benefit from learning what offends people and learning what in fact their point of view is. I think we all learn from that, but unless we all talk about it, you don’t learn. In some ways, unless you cast a white Christmas Eve, you don’t learn that that’s wrong, you don’t learn that that’s not OK with people.”

Even though Avenue Q is closed, David Lyman notes that the issue of authenticity in racial casting retains great currency, not only in Cincinnati, but at this particular theatre. “Warsaw Federal incline Theatre is doing Anything Goes in June,” notes Lyman. “What are we going to see there? We’ve got these two Chinese guys. Are they going to make any effort to find Asians? I don’t know. We’re going to find out.”

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

March 1st, 2016 § § permalink

When a student-devised piece of theatre begins as The Politics of Dancing, an examination of relationships springing from Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, and is ultimately produced as This Title Has Been Censored, something is amiss. When a student production scheduled for multiple performances in a college theatre department’s mainstage season ends up as a single workshop performance with rudimentary tech given during a final exam period, something is strange. When an original work of theatre begins to address gender roles and is immediately downsized, something is troubling. When these actions were prompted because an inchoate project was judged by departmental leadership based solely on a few preliminary scenes reviewed four months before the work was to be finished, something seems wrong.

But those are all aspects of what transpired over the past several months in the theatre department of Oklahoma State University. The Politics of Dancing, which had been announced as part of the school’s 2015-16 mainstage season in the Vivia Locke Theatre, which seats some 500 patrons, was to have been presented in February; the rest of the season included A.R. Gurney’s What I Did Last Summer, and The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee. Instead of The Politics of Dancing, the school produced John Cariani’s Almost, Maine.

So what exactly happened to The Politics of Dancing? In October, Professor Jodi Jinks, who holds the school’s Mary Lou Lemon Endowed Professorship for Underrepresented Voices, shared a few short scenes from the work the students had begun to create with the head of the department, which both she and the students say weren’t necessarily representative of what the finished work would be like, given the evolving nature of any devised theatre.

“Professor Jinks allowed us as an ensemble to explore what we wanted. It kind of naturally flowed in that direction,” said student Jessica Smoot via e-mail. “Honestly I think it just came from the fact that you can’t properly explore romantic relationships without understanding gender, and since it is such a hot topic these days it became a much more fascinating subject to explore.”

Student Joshua Arbaugh said, also via e-mail, “The focus of the show never switched from ‘general relationships.’ Gender was only one subject that the show was going to touch on. There was never a time that we as a group decided that the show would be about gender. However, gender and gender roles play a big part in relationships so we devoted a healthy amount of time early in our devising process to explore the many facets of gender in our research and our work. We had no idea that this would displease anyone and did not believe that it was a divergence in our declared ‘focus’.”

Prof. Jinks says that she shared some very early drafts of Dancing on October 19 and two days later department chair Andrew Kimbrough met with the students involved in the production and, in Jinks’s words, “dropped the bomb, or gave the option.”

“We could change the direction we were heading in and create something for our [mainstage] audience, or the students could say what they wanted to say and move to the studio,” explained Jinks.

The audience, as described by students in their meeting with Kimbrough, was “over 50, white and Republican,” according to Jinks in an interview with the campus newspaper The O’Colly. Kimbrough told The O’Colly, “I believed the students’ assessment of the audience was accurate.” From The O’Colly:

The theater department advertised the play as a production that “examines the mating rituals of our planet’s most advanced and complicated species,” according to a department brochure.

“I was seeing an evolution of work that was, one, not on the topic that was proposed, (and) two, that tended to be one-sided in its address of transgender issues,” Kimbrough said.

Kimbrough said he visited the class and requested that if the students continued with “The Politics of Dancing,” they keep in mind the type of audience they would be performing for.

“Even though they were moving in a new direction, they were never asked to abandon the topic but simply to proceed from the vantage of mid-October with our current audience in mind,” Kimbrough said. “And I believe when you’re running a business, this is the No. 1 rule. You must create work that has your audience in mind.”

After a weekend of consideration, according to Jinks, the students decided to move the production to the smaller studio. “Ultimately,” said Jinks, “they decided to perform the play they originally wanted to write.”

But that plan hit a snag when Jinks and the students were later informed that their production in the studio would have no production support, because the technical departments, in her description, “could not do two things that close together or at the same time,” with the substituted mainstage show cited as a conflict.

“They were offered the studio and thought they could do that,” said Jinks. “That was the option they were presented, and slowly, bit by bit, it was removed.”

Regarding Kimbrough’s position on the project, Arbaugh wrote, “The idea of him bullying our work until he was ‘comfortable’ with it was too great a cost. However, none of us would have chosen to lose departmental support and our spot in the season. We were all blindsided by the decision and I would say it’s because we gave the “wrong answer.”

Arbaugh continued, saying, “The Politics of Dancing was supposed to be a true test of all our talents. We, as students of the theater, were to use everything we had learned in this in this endeavor. When it was cancelled, it was like a big door was slammed in all of our faces saying, ‘who you are is inappropriate and what you have to contribute has no value.’ So self-esteems suffered and even now there is anxiety in the department.”

So why did the show become This Title Has Been Censored?

“As a class,’ wrote Smoot, “we found that using the source materials we were initially assigned (A Doll’s House and the “Politics Of Dancing” song) were becoming more of a hindrance to our creativity, so we scrapped them from the show. This, along with the struggles we had faced through the process, made the show look completely different from what it was initially intended to be – but that can be expected with devised theatre! We wanted to rename the show in a way that acknowledged the struggles in the process. The final product still discussed gender, but in a much more personal way that drew from many of our personal experiences and life moments interspersed with current events revolving around gender.”

At the show’s single performance, Jinks wrote the following in the program:

During the first few weeks of this current semester the Devised Theatre class was developing a different play than the one you will see today. It was called the The Politics of Dancing and it was to be performed in the Vivia Locke in February of 2016. The devised class would build it and perform it, with me serving as facilitator and director. Over a year ago I made preliminary choices to jump start the process with the class. We were to deconstruct Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House and build a new piece by looking at Ibsen’s work through the lens of gender identification, transgenderism and gender politics – subjects which are omnipresent in the media of late. However other lessons (struggles) interrupted that process.

Jinks believes that some of the problems that arose came from many in the theatre department being unfamiliar with company-created theatre.

“I was working with faculty who have no experience with devising, but I thought we were addressing those needs, “ she said, noting that there was “some rigidity, some pushback even before it was canceled.” Jinks said she discounted that response, calling it “irrelevant.”

“It was so early in the process, the play could have gone in any direction. We had four months. They canceled it because the idea was threatening.”

Jinks described a series of meetings with the dean, the provost, the faculty council and the Office of Equal Opportunity between November and early February.”

“I was met with a wall of silence and denial,” she said, “I’d like them to tell me why it isn’t a denial of academic freedom of speech.”

In February, Jinks met with Kimbrough and the provost.

“I gave both men by action requests, “ she said. “One, Andrew was to acknowledge that an error was made in canceling The Politics of Dancing. Two, Andrew would apologize to the department – faculty, staff and students. Three, the department would write policy so that this doesn’t happen again. Four, there would be a recusal from professional advancement discussion by Andrew over me.”

“Andrew said no to one and two,” she continued. “He did say he would apologize for not having everyone in the same room at the same time to discuss the issue.”

Jinks has been at Oklahoma State University for five years, four of those on a tenure track. She will be up for tenure review in two years.

* * *

Dr. Andrew Kimbrough was contacted by e-mail and asked for an on the record interview regarding this situation. His entire reply was as follows

I’ll be happy to speak to you once our challenge is fully resolved and behind us. I’m learning a lot, and would appreciate more professional response. Thanks.

A second request, noting that his replies to The O’Colly would be the only opportunity for his voice to be heard in this article, received no reply.

Since Dr. Kimbrough asked for more professional response, it seems only appropriate to provide him with some.

My first thought is to say that if indeed you are not already well-versed, Dr. Kimbrough, you should become familiar with the process of devised theatre as an evolutionary process that cannot necessarily be given a label more than half a year in advance and be expected to stick to exactly the original premise. That said, devised theatre must have a place in the OSU theatre department with the full resources of the department, because devised theatre is important both academically and creatively; it is essential that theatre students of today learn about and experience devised, collaborative works to prepare them forprofessional careers.

Please reconsider your statements and overall perspective, Dr. Kimbrough, about the audience being the most important arbiter of what students perform at OSU. Your assertion in The O’Colly, “When you’re running a business, this is the No. 1 rule,” seems profoundly misplaced within an academic theatre program. Students should not be educated according to the perceived preferences of the local consumer marketplace, but rather taught in order to develop their talent, their skills, and their knowledge so that they themselves are competitive in the marketplace of theatre. Indeed, if your position on why we make theatre were voiced by the artistic director of most of America’s not-for-profit theatres, that individual would be questioned by many in the field for abdicating the role of an artistic leader and kowtowing to lowest common denominator sentiments. Yes, there are financial demands on all theatres, and theatre cannot survive without an audience, but those concerns need to operate in balance with the creative impulse. To visit those concerns on students who have paid for a complete theatrical education, with audience satisfaction superseding the education imperative, seems a corruption of the role of academics.

Dr. Kimbrough, your students have the same sentiments as I do.

Jessica Smoot wrote, “He sees this department as a business, and while that has been very beneficial when building the department, it can become dangerous for the creative integrity of the department, which I think is very detrimental to our department. There are ways to warn people to not come if you’re easily offended – add ratings, label shows as avant garde or fringe – but don’t take freedom of speech from the students. We will spend the rest of our lives having to worry about where the money to support our art will come from. Let us have some freedom while we still have the ability to not worry about finance, so that when producing our work becomes harder, we will be creating better quality work from the start because we have already had a chance to practice.”

Joshua Arbaugh wrote, “How could we possibly predict what every audience member came to see and how do we know whether or not there is a completely different audience that has simply been alienated by these ‘choices’ in the past. When someone says, “We need to cater to our audience.” That person is really saying, ‘what’s going to be the most digestible to the kinds of people I personally want to come to these shows.’ My answer is no, the theater season should not be selected to impress Andrew’s hetero-normative white friends.”

Finally Dr. Kimbrough, while one would hope you would do so in all things, it’s particularly incumbent upon you when your department has an endowed chair for underrepresented voices to always demonstrate genuine concern and respect for the students who embody those voices and the professor directly charged with serving them. When you offered the students the opportunity to pursue their vision in a smaller space due to your concerns over the marketability of a piece which appeared to be leaning towards a consideration of gender, and they were subsequently informed that they would receive no technical support and no promotion, you were effectively suppressing art on that subject, regardless of your intent.

I am very fond of Almost Maine (and its author, John Cariani) and I’ve seen Cabaret numerous times, but I don’t think those are shows which deeply explore gender issues and represent efforts at diversity, as you suggested to The O’Colly. You need to redress the impression you have instilled in your students as quickly as possible, by planning for work which explicitly examines that topic, either on the mainstage or for a sustained run in the studio. In addition, you would do well to endorse a new student devised work on the subject of gender in modern society that you will stand behind as firmly as you do The 39 Steps or As You Like It (which does have a bit of gender bending of its own, rendered safe by being 400 years old).

On top of all of this, Dr. Kimbrough, to speak your language for a moment, if money is an important consideration, your actions may be alienating a presumably important donor. To cite an article in The Gayly:

“Literally, the name of this endowed professorship is ‘The Mary Lou Lemon Endowed Professorship for underrepresented voices,’” said Robyn Lemon, daughter of the late Mary Lou Lemon. “Not allowing these students to perform this play contradicts the very reason this entire professorship was set up.”

The bottom line here is that the education of students must come first at a university, and that education must not be simply current but forward-thinking in its philosophy, its pedagogy and its practice. The Politics of Dancing isn’t likely to be resurrected; its moment has passed. But if Oklahoma State University theatre wishes to stand for excellence, if it wants to both compete for students and for the students it graduates to be competitive, it must make very clear that it embraces students no matter their gender identity, their race, the ability or disability – in short, it must be genuinely and consistently inclusive – and it should use its stages to make that clear to the entire university, the local community and beyond.

* * *

One last word: as The O’Colly researched its story on this subject, Kimbrough acknowledged that he attempted to have the story quashed. He was quoted saying, “I think it would be in the best interest of the department if there was no negative publicity of this incident.” When there are charges of censoring a piece of theatre by reducing its potential audience significantly and withdrawing support from it, that’s not a very good time to also try to keep the story from being told. As is so often the case, efforts to avoid negative stories only lead to yet more inquiry and more concern. That holds true for decisions to cease answering questions about a subject in the public eye. Theatre is about telling stories and very often, about revealing truths. The story of The Politics of Dancing is incomplete. It is up to Oklahoma State Theatre to bring it to an honest, open, inclusive and satisfying ending for all concerned.

December 23rd, 2015 § § permalink

Still from NYGASP video spot on YouTube

Oh, New York Gilbert and Sullivan Players, what are we going to do with you?

It was surprising to many that you thought you could do a “classic” yellowface Mikado in New York in 2015. But you also responded pretty quickly once there was an outcry against the practice, with the first blog posts of dismay (from Leah Nanako Winkler, Erin Quill, Ming Peiffer and me) posted on Tuesday and Wednesday and the production canceled by midnight on Friday morning. You’ve promised to bring your Mikado into alignment with current sensibilities at some point in the future, and I’m one of the many people who had cordial conversations with your executive director David Wannen in the wake of the September controversy.

So one can’t help be brought up short by your current commercial for The Pirates of Penzance, the production which replaced The Mikado at NYU’s Skirball Center. Shot in the Old Town Bar just north of Union Square, it features pub denizens having a Gilbert & Sullivan sing-off with some piratical looking men, as well as some geriatric British naval officers. All in good fun, it seems.

So why is there an admittedly brief shot in the ad of three yellowface geishas in a bar booth being leered at (by telescope, no less) by the British officers? Why is there still yellowface as part of advertising a production that was scheduled to eradicate yellowface?

Now I’m fully prepared to acknowledge this is probably an old TV spot, and all that has been changed is the superimposed show title, venue and number to call for tickets at the end. In fact, having watched New York television for much of my life, I’d say this spot could be quite old, and may well have emanated from days when Pirates, The Mikado and H.M.S. Pinafore were the bedrock of your repertory.

But in light of all that has happened over the past four months, seeing those faux-Asian women giggling behind their fans seems wholly out of place, if not a slap at those who advocated for a more enlightened take from you going forward. I acknowledge the effort and cost of recutting, or even reshooting, a commercial, but it might have been wise for you to not keep propagating the very imagery that led you to decide to cancel your production.

There’s no way to know whether you’re buying broadcast or cable time for the spot, but you just posted it to YouTube at the beginning of this month. This morning, the spot was featured in an e-mail blast you sent. So this possibly vestigial ad is still very much part of your marketing.

As I noted in a conference call with David Wannen, it is not lost on us that Albert Bergeret, the company’s artistic director, has not – so far as I know, and I’d be happy to be corrected – publicly expressed his support for the decision to remove The Mikado from your repertoire pending a reconception. Even this brief glimpse of yellowface suggests that the message of respecting ethnicities other than white hasn’t really sunk in. In fact, this could be seen by some as you winking at the controversy and telling your regular audiences that your “traditions” will be upheld, even if your sole intent was to economize and recycle an existing ad.

C’mon NYGASP, you said you were going to do better. You’ve taken some important steps, but it seems you’ve still got a ways to go.

Thanks to Barb Leung for sharing the e-mail and video from NYGASP.

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

December 23rd, 2015 § § permalink

New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players commercial

Oh, New York Gilbert and Sullivan Players, what are we going to do with you?

It was surprising to many that you thought you could do a “classic” yellowface Mikado in New York in 2015. But you also responded pretty quickly once there was an outcry against the practice, with the first blog posts of dismay (from Leah Nanako Winkler, Erin Quill, Ming Peiffer and me) posted on Tuesday and Wednesday and the production canceled by midnight on Friday morning. You’ve promised to bring your Mikado into alignment with current sensibilities at some point in the future, and I’m one of the many people who had cordial conversations with your executive director David Wannen in the wake of the September controversy.

So one can’t help be brought up short by your current commercial for The Pirates of Penzance, the production which replaced The Mikado at NYU’s Skirball Center. Shot in the Old Town Bar just north of Union Square, it features pub denizens having a Gilbert & Sullivan sing-off with some piratical looking men, as well as some geriatric British naval officers. All in good fun, it seems.

So why is there an admittedly brief shot in the ad of three yellowface geishas in a bar booth being leered at (by telescope, no less) by the British officers? Why is there still yellowface as part of advertising a production that was scheduled to eradicate yellowface?

Now I’m fully prepared to acknowledge this is probably an old TV spot, and all that has been changed is the superimposed show title, venue and number to call for tickets at the end. In fact, having watched New York television for much of my life, I’d say this spot could be quite old, and may well have emanated from days when Pirates, The Mikado and H.M.S. Pinafore were the bedrock of your repertory.

But in light of all that has happened over the past four months, seeing those faux-Asian women giggling behind their fans seems wholly out of place, if not a slap at those who advocated for a more enlightened take from you going forward. I acknowledge the effort and cost of recutting, or even reshooting, a commercial, but it might have been wise for you to not keep propagating the very imagery that led you to decide to cancel your production.

There’s no way to know whether you’re buying broadcast or cable time for the spot, but you just posted it to YouTube at the beginning of this month. This morning, the spot was featured in an e-mail blast you sent. So this possibly vestigial ad is still very much part of your marketing.

As I noted in a conference call with David Wannen, it is not lost on us that Albert Bergeret, the company’s artistic director, has not – so far as I know, and I’d be happy to be corrected – publicly expressed his support for the decision to remove The Mikado from your repertoire pending a reconception. Even this brief glimpse of yellowface suggests that the message of respecting ethnicities other than white hasn’t really sunk in. In fact, this could be seen by some as you winking at the controversy and telling your regular audiences that your “traditions” will be upheld, even if your sole intent was to economize and recycle an existing ad.

C’mon NYGASP, you said you were going to do better. You’ve taken some important steps, but it seems you’ve still got a ways to go.

Thanks to Barb Leung for sharing the e-mail and video from NYGASP.

December 3rd, 2015 § § permalink

Renée Elise Goldsberry, Lin-Manuel Miranda and Phillipa Soo in Hamilton (Photo by Joan Marcus)

In the wake of the recent casting controversies over Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop and Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India, there have been a number of online commenters who have cited Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton as a justification for their position in the debate. What’s intriguing is that Hamilton has been offered up both as evidence of why actors of color must have the opportunity to play both characters or color and characters not necessarily written as characters of color – but it has also been used to say that anything goes, and white actors should be able to play characters of color as well.

In the Broadway production of Hamilton, the characters are historical figures who were all known to have been white, but they are played by actors of many races and ethnicities, notably black, Latino and Asian. My position on non-traditional (or color-blind or color-specific) casting is that it is not a “two-way street,” and that the goal is to create more opportunities for actors of color, not to give white actors the chance to play characters of color.

As it happens, I had an interview scheduled with Miranda last week, the night before Thanksgiving. Race wasn’t the subject at all, however. We were speaking about his experiences in, and views on, high school theatre, for Dramatics magazine, a publication of the Educational Theatre Association (ask a high school thespian for a copy). But when I finished the main interview, and had shut off my voice recorder, I asked Miranda if he would be willing to make any comment regarding the recent casting situations that had come to light. He was familiar with The Mountaintop case, but I had to give him an exceptionally brief précis of what had occurred with Jesus in India. He said he would absolutely speak to the issue, and I had to hold up my hand to briefly pause him as he rushed to start speaking, while I started recording again.

“My answer is: authorial intent wins. Period,” Miranda said. “As a Dramatists Guild Council member, I will tell you this. As an artist and as a human I will tell you this. Authorial intent wins. Katori Hall never intended for a Caucasian Martin Luther King. That’s the end of the discussion. In every case, the intent of the author always wins. If the author has specified the ethnicity of the part, that wins.

“Frankly, this is why it’s so important to me, we’re one of the last entertainment mediums that has that power. You go to Hollywood, you sell a script, they do whatever and your name is still on it. What we protect at the Dramatists Guild is the author’s power over their words and what happens with them. It’s very cut and dry.”

This wasn’t the first time Miranda and I have discussed racial casting. Last year, we corresponded about it in regard to high school productions of his musical In The Heights, and his position on the show being done by high schools without a significant Latino student body, which he differentiated from even college productions.

Lin-Manuel Miranda, Karen Olivo and the company of In The Heights (Photo by Joan Marcus)

“The joy of In The Heights runs both ways to me,” he wrote me in early 2014. “When I see a school production with not a lot of Latino students doing it, I know they’re learning things about Latino culture that go beyond what they’re fed in the media every day. They HAVE to learn those things to play their parts correctly. And when I see a school with a huge Latino population do Heights, I feel a surge of pride that the students get to perform something that may have a sliver of resonance in their daily lives. Just please God, tell them that tanning and bad 50’s style Shark makeup isn’t necessary. Latinos come in every color of the rainbow, thanks very much.

“And I’ve said this a million times, but it bears repeating: high school’s the ONE CHANCE YOU GET, as an actor, to play any role you want, before the world tells you what ‘type’ you are. The audience is going to suspend disbelief: they’re there to see their kids, whom they already love, in a play. Honor that sacred time as educators, and use it change their lives. You’ll be glad you did.”

Daveed Diggs and the company of Hamilton (Photo by Joan Marcus)

Anticipating the flood of interest in producing Hamilton once the Broadway production and national tours have run their courses, I asked Miranda whether the acting edition of the script of Hamilton will ultimately be specific about the cast’s diversity, and whether, either at the college level or the professional level, he would foresee a situation where white actors were playing leading roles.

“I don’t have the answer to that. I have to consult with the bookwriter, who is also me,” he responded. “I’m going to know the answer a little better once we set up these tours and once we set up the London run. I think the London cast is also going to look like our cast looks now, it’s going to be as diverse as our cast is now, but there are going to be even more opportunities for southeast Asian and Asian and communities of color within Europe that should be represented on stage in that level of production.

“So I have some time on that language and I will find the right language to make sure that the beautiful thing that people love about our show and allows them identification with the show is preserved when this goes out into the world.”

Authorial intent, y’all. Authorial intent.

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

December 3rd, 2015 § § permalink

Phillipa Soo, Lin-Manuel Miranda and Renée Elise Goldsberry in Hamilton (Photo by Joan Marcus)

In the wake of the recent casting controversies over Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop and Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India, there have been a number of online commenters who have cited Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton as a justification for their position in the debate. What’s intriguing is that Hamilton has been offered up both as evidence of why actors of color must have the opportunity to play both characters or color and characters not necessarily written as characters of color – but it has also been used to say that anything goes, and white actors should be able to play characters of color as well.

In the Broadway production of Hamilton, the characters are historical figures who were all known to have been white, but they are played by actors of many races and ethnicities, notably black, Latino and Asian. My position on non-traditional (or color-blind or color-specific) casting is that it is not a “two-way street,” and that the goal is to create more opportunities for actors of color, not to give white actors the chance to play characters of color.

As it happens, I had an interview scheduled with Miranda last week, the night before Thanksgiving. Race wasn’t the subject at all, however. We were speaking about his experiences in, and views on, high school theatre, for Dramatics magazine, a publication of the Educational Theatre Association (ask a high school thespian for a copy). But when I finished the main interview, and had shut off my voice recorder, I asked Miranda if he would be willing to make any comment regarding the recent casting situations that had come to light. He was familiar with The Mountaintop case, but I had to give him an exceptionally brief précis of what had occurred with Jesus in India. He said he would absolutely speak to the issue, and I had to hold up my hand to briefly pause him as he rushed to start speaking, while I started recording again.

“My answer is: authorial intent wins. Period,” Miranda said. “As a Dramatists Guild Council member, I will tell you this. As an artist and as a human I will tell you this. Authorial intent wins. Katori Hall never intended for a Caucasian Martin Luther King. That’s the end of the discussion. In every case, the intent of the author always wins. If the author has specified the ethnicity of the part, that wins.

“Frankly, this is why it’s so important to me, we’re one of the last entertainment mediums that has that power. You go to Hollywood, you sell a script, they do whatever and your name is still on it. What we protect at the Dramatists Guild is the author’s power over their words and what happens with them. It’s very cut and dry.”

This wasn’t the first time Miranda and I have discussed racial casting. Last year, we corresponded about it in regard to high school productions of his musical In The Heights, and his position on the show being done by high schools without a significant Latino student body, which he differentiated from even college productions.

Lin-Manuel Miranda, Karen Olivo and the company of In The Heights (Photo by Joan Marcus)

“The joy of In The Heights runs both ways to me,” he wrote me in early 2014. “When I see a school production with not a lot of Latino students doing it, I know they’re learning things about Latino culture that go beyond what they’re fed in the media every day. They HAVE to learn those things to play their parts correctly. And when I see a school with a huge Latino population do Heights, I feel a surge of pride that the students get to perform something that may have a sliver of resonance in their daily lives. Just please God, tell them that tanning and bad 50’s style Shark makeup isn’t necessary. Latinos come in every color of the rainbow, thanks very much.

“And I’ve said this a million times, but it bears repeating: high school’s the ONE CHANCE YOU GET, as an actor, to play any role you want, before the world tells you what ‘type’ you are. The audience is going to suspend disbelief: they’re there to see their kids, whom they already love, in a play. Honor that sacred time as educators, and use it change their lives. You’ll be glad you did.”

Daveed Diggs and the company of Hamilton (Photo by Joan Marcus)

Anticipating the flood of interest in producing Hamilton once the Broadway production and national tours have run their courses, I asked Miranda whether the acting edition of the script of Hamilton will ultimately be specific about the cast’s diversity, and whether, either at the college level or the professional level, he would foresee a situation where white actors were playing leading roles.

“I don’t have the answer to that. I have to consult with the bookwriter, who is also me,” he responded. “I’m going to know the answer a little better once we set up these tours and once we set up the London run. I think the London cast is also going to look like our cast looks now, it’s going to be as diverse as our cast is now, but there are going to be even more opportunities for southeast Asian and Asian and communities of color within Europe that should be represented on stage in that level of production.

“So I have some time on that language and I will find the right language to make sure that the beautiful thing that people love about our show and allows them identification with the show is preserved when this goes out into the world.”

Authorial intent, y’all. Authorial intent.

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

November 16th, 2015 § § permalink

Robert Branch and Camila Christian in The Mountaintop at Kent State University

In the many press accounts of director Michael Oatman casting a white man to play Dr. Martin Luther King in Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop, stories have all acknowledged Oatman’s original concept of splitting the role between black and white actors. His intent was, in his words:

“I truly wanted to explore the issue of racial ownership and authenticity. I didn’t want this to be a stunt, but a true exploration of King’s wish that we all be judged by the content of our character and not the color of our skin,” said Oatman about his non-traditional cast. “I wanted the contrast . . . I wanted to see how the words rang differently or indeed the same, coming from two different actors, with two different racial backgrounds.”

That narrative has prevailed, even when Katori Hall let it be known that she did not and would not ever approve of a white actor playing King in her play. Just as I had in my original post on this incident, she wondered why the black actor sharing the role was so little in evidence. Even after speaking with Oatman, Hall wrote:

“It’s true that Oatman only fell halfway off the ‘turn-up’ truck; the white actor was indeed sharing the role with another black actor. But the fact that this mystery actor has remained nameless further demonstrates the erasure of the black body in this experiment. Even on the school newspaper’s website, only the white actor’s name is listed.”

As it turns out, the reason this black actor is so scarce is because no black actor performed in the role of Martin Luther King at Kent State. As part of an interview with Oatman, the Akron Beacon Journal reports:

“At Kent State, Oatman originally double cast the King role, with white actor Robert Branch for three performances and a black actor for five shows. When more than one black actor dropped out due to family and other personal issues, Branch, whom Oatman described as one of the best actors he’s ever seen, assumed all eight performances.”

Even if one gives credence to Oatman’s intellectual basis for attempting to split the role, it evaporated along with the unnamed black actor, regardless of Branch’s talent. At that point, the already unjustifiable production should have been irrevocably abandoned, since the entire conceptual underpinning had come undone. What Oatman did was not a half-measure, as Hall was apparently led to believe, as we were all led to believe, but indeed the complete erasure of a black body as she had feared. There was no rationalization left, yet despite the intense press interest since Hall published her essay on TheRoot.com, Oatman at best quietly allowed a myth to be sustained, or at worst actively sought to keep the truth of the production secret to anyone interested, until this interview.

That this fact is virtually an aside in the Beacon Journal’s follow-up, which largely affords an unfettered opportunity for Oatman to advance his reasoning yet again, with nothing but quotes from Hall’s essay as pushback, seems a conscious effort to minimize the facts of the narrative. In citing supportive messages from friends on Oatman’s Facebook page, and noting that there were only a few walkouts as if that made the casting acceptable, the Beacon Journal is complicit in failing to address the willful lack of fidelity to the playwright’s intent. Where are the quotes from Hall’s friends, who were outraged. In addition, by saying at one point of Hall that “she railed,” rather than “she wrote,” there is also an implication that Hall’s thoughts on this issue were somehow not presented in an “acceptable” manner, another unfortunate choice.

So the summary of the Kent State Mountaintop story is: the creative decision was faulty to begin with, ultimately abandoned (no matter what the reason) and possibly kept secret even as scrutiny was focused on the production. Whether by omission or misdirection, Oatman has compounded his troubling creative decision immeasurably.

Though Oatman has said he wouldn’t make this particular choice again, he seems unbowed by the response from Hall and the playwriting community. He told the Journal:

“I think artists get too touchy about this kind of stuff,” he said. “I think whenever you make a controversial decision like this you have to allow the audience their space to react as they’re going to react. That’s what theater is about.”

If a director’s ethical and legal responsibility to other artists is dismissed as being “touchy,” indeed by someone who is primarily a playwright, any questions about Oatman’s judgment in this case should no longer be in question. He finds widely accepted professional practices to be a nuisance, when they are fundamental to the field he works in.

If his goal was to court controversy, Oatman has probably succeeded beyond his wildest dreams, and there may be more yet to come. But if his goal was to illuminate Katori Hall’s play for audiences, it’s quite clear that he failed, even if people applauded. He may have thought originally that what he was doing wasn’t a stunt, but in the end, that’s just what it turned out to be.

Update, November 16, 4:45 pm: In sharing my post on Facebook, Katori Hall prefaced it, in part, with the following statement:

“…When I spoke to Michael Oatman via phone October 27th, he never disclosed the fact that the black actor never went on, even when I questioned the validity of his social experiment of seeing if the ‘words rang differently or indeed the same, coming from two different actors, with two different racial backgrounds.’

I learned that the black actor never went on when Oatman was interviewed Friday night by Don Lemon on CNN. Surprise, surprise.

Many journalists in the media have portrayed me as outraged (The Wrap, NY Daily News, Washington Times, Playbill). I have supposedly ‘fumed’. I have supposedly ‘slammed.’ Shout out to TIME and TheRoot.com who used much more honest language. Yes, I criticized the casting choice and yes I explained my position why….

Yes, it is unfortunate that in 2015, a young black female artist who demands that her work be respected and puts forth a valid and articulate response is characterized as merely throwing a temper tantrum.”

Howard Sherman is the interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts School of Drama.

November 16th, 2015 § § permalink

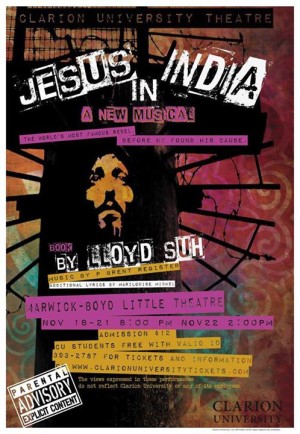

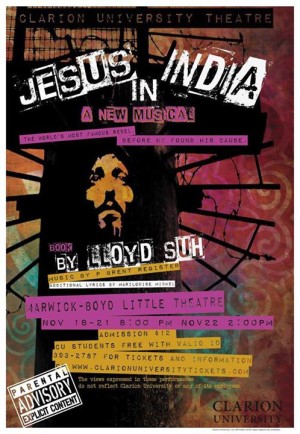

Poster for Jesus in India at Clarion University

“What will you learn?” asks the home page of the website of Clarion University in Pennsylvania. In the wake of the school’s handling of the casting of white students in Asian roles in Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India, and the playwright’s withdrawal of production rights upon learning this fact, it’s unclear at best, disturbing at worst, to consider what Clarion wants students to learn about race and about the arts.

Based on what is appearing in the press, they are learning to blame artists for wanting to see their work represented accurately. They are learning to attack artists when the artists defend their work. They are learning that a desire to see race portrayed with authenticity is irrelevant in an academic setting. They are learning that Clarion seems unaware of the issues that have fueled racial unrest on campuses around the country, most recently with flashpoints at the University of Missouri and Yale University. They are learning that when a community is overwhelmingly white, concerns about race aren’t perceived as valid.

In an essay published in the Chronicle of Higher Education on Friday, Marilouise Michel, professor of theatre and director of the canceled production, wrote, “I have intentionally left out the name of the playwright and the piece that we were working on as I do not wish to provide him with publicity at the expense of the fine and viable work of our students.” What’s peculiar about that statement is that until 1:30 pm that day, when he released a statement, the playwright hadn’t sought for this issue to be public in any way. It was Clarion that had contacted the press, Clarion which had released his correspondence with Michel, and Clarion which used a professional public relations firm to issue a statement about the situation from the university and its president. It reads, in part:

The university claims their intent from the start was to honor the integrity of the playwright’s work, and the contract for performance rights did not specify ethnically appropriate casting. Despite the university’s attempt to give Suh a page in the program to explain his casting objections and a stage speech given by a university representative on the cast’s race, Suh rejected any solutions other then removing the non-Asian actors or canceling the production.