January 25th, 2016 § § permalink

American Idiot at Enfield High casting notice

“Welcome to a new kind of tension.

All across the alienation.

Where everything isn’t meant to be okay.”

The details are very sketchy. The drama director hasn’t yet responded to a call or e-mail. The school principal said that he “wasn’t comfortable” talking about it without the approval of the superintendent, which he did say he would seek. The licensing house that handles the rights for the musical has not responded to an e-mail inquiry about approved changes (although the company’s president is overseas). An anonymous source who provided some background materials won’t be named publicly because they fear recriminations against their child in the school system.

But here’s what’s known: the Enfield High School Lamplighters, in Enfield CT, were scheduled to perform the musical American Idiot this spring, with auditions set for January 13 and 14, with callbacks on January 15. Performances were set for early May.

On January 17, Nate Ferreira, faculty director of the Lamplighters, sent a general e-mail to the school community which included the following statement:

As most of you know, we had a drama club meeting this past Wednesday to discuss the details of producing “American Idiot” as our final show this school year. Due to the mature content of the original production, I have been working with the publisher to modify the script, to ensure that it would be appropriate for a high school group to perform.

This project was very successful, and we feel that the modified script and production notes maintain the integrity of the show, while removing profanity and the more adult scenarios in the original Broadway production. The publisher is even starting the process of turning our edited version of the script into their official “School Edition” of the play, to allow other high schools to easily perform this play in the future.

As I’ve stated at our student/parent meetings during the past two school years: this extended production process was intended to allow us to work on a show that most of the kids were extremely excited about, while continuing the award-winning Lamplighters tradition of exploring serious issues in a mature and responsible way. In the same way that our presentation of the student-authored and directed “Happily Never After” last year did an excellent job of handling the difficult issues of domestic abuse and justifiable homicide, “American Idiot” opens discussion about many issues of young adulthood.

Unfortunately, a very small number of extremely vocal people have complained about our choice of production. This led to Mr. Longey [principal Andrew Longey] and I meeting on Friday to discuss a change in our choice of production. To be clear, Mr. Longey did not force us to change – he and I took a long and careful look at all aspects of the show, and all arguments on either side. At this late stage it is very difficult to switch to a different play, but I do feel that it is best for us to set aside “American Idiot” for the time being. I want ALL of our club members to be able to be a part of our musical, and I want to be absolutely certain that the play happens at all.

Currently, the last post on the Lamplighters Facebook page is a reference to a meeting on January 20. There is no announcement of a new show for the spring.

Billie Joe Armstrong in American Idiot on Broadway

While hopefully more details will fall into place, there is someone else who would like to see the production of American Idiot go on. I reached out to Christine Jones, who designed the set for the Broadway production of American Idiot, in an effort to make Green Day frontman Billie Joe Armstrong, the composer and lyricist of the show, aware of the situation. Armstrong sent back the following message through Jones in a little over an hour’s time, and reportedly also posted it on Instagram (it is reproduced here precisely as he wrote it):

dear Enfield high school board,

It has come to my attention that you cancelled your high school theater production of American Idiot.

I realize the content of the Broadway production of AI is not quite “suitable” for a younger audience.

However there is a high school rendition of the production and I believe that’s the one Enfield was planning to perform which is suitable for most people.

it would be a shame if these high schoolers were shut down over some of the content that may be challenging for some of the audience. but the bigger issue is censorship. this production tackles issues in a post 9/11 world and I believe the kids should be heard. and most of all be creative in telling a story about our history.

I hope you reconsider and allow them to create an amazing night of theater!

as they say on Broadway ..

“the show must go on!”

rage and love

Billie Joe Armstrong

P.S. I love that your school is called “Raiders”

Mr. Ferreira seems to have followed every appropriate step in the process of planning this show for Enfield High, but the production has been suspended. Yet he is still hoping that American Idiot will be done at some point. So is its author, who has apparently granted permission to alter the work to make it more appropriate in a school setting. Perhaps there’s still room for dialogue, and Enfield High can still give its students the opportunity to take on challenging, modern work.

If indeed a few parents resulted in spoiling this experience for all of the Lamplighters, that would be a real shame that denies opportunity to many in order to satisfy the views of a few. I’d rather at this turning point, the school was directing the students where to go – towards work that will help them grow as performers and as people, towards work that provokes rather than palliates. I hope they’re allowed to have the time of their lives with American Idiot, sooner than later.

Update, January 25, 10:45 pm: In an article in The Hartford Courant that went online an hour ago, the Lamplighters director Mr. Ferreira represents his intended revisions to the text of American Idiot in a markedly different framework than he did in his e-mail to the school community. Per The Courant:

Ferreira said the performance included “a lot of swearing,” which Ferreira said he’d hoped to limit or eliminate pending approval from the publisher. “There’s some heavy drug use and graphic sex scenes, not things we were going to depict to the extent they did in the original show.”

This is a far cry from the tone of Ferreira’s e-mail, which declared:

“I have been working with the publisher to modify the script, to ensure that it would be appropriate for a high school group to perform. This project was very successful, and we feel that the modified script and production notes maintain the integrity of the show, while removing profanity and the more adult scenarios in the original Broadway production. The publisher is even starting the process of turning our edited version of the script into their official “School Edition” of the play, to allow other high schools to easily perform this play in the future.”

In my original post, I said it seemed that Ferreira had followed the appropriate steps, and now by his own admission, that is clearly not the case; he did not have approval to make any changes, he had not undertaken a successful project that would influence future productions. While I think there may still be opportunities for Enfield students to benefit from performing in American Idiot, they cannot do so in any version not fully approved by the authors and their representatives.

I don’t support a small number of parents ending the opportunity for the majority of the Lamplighters, but I also don’t support Ferreira’s effort to aggrandize his own sanitized version of the text. This has been a lose-lose proposition at Enfield High: the show has been shut down without being properly defended, and there has been an effort to misrepresent to the community that Ferreira’s text was authorized and even praised, obscuring the authors’ rights and copyright protections. Unfortunately, the students lose as well.

Update, January 26, 6:30 am: I received the following e-mail from Nate Ferreira at 1:55 am this morning, more than 17 hours after I first attempted to contact him, 14 hours after Principal Longey said he could not comment without the approval of the superintendent, 11 hours after my original post went online, and three hours after the previous update was posted. It is reproduced in its entirety precisely as it was received (except for the lack of paragraph spacing, which is a formatting problem on my site).

Thank you for reaching out to me. I’m sorry that I didn’t see your email until after you had finished writing your post.

Here are some more details regarding our decision not to perform American Idiot. As the director of the school’s drama club, I was very excited to produce American Idiot, and to explore the issues raised by the material.

Due to the fact that some of our club families were not comfortable with their kids being involved in the show, it was my decision to perform a different show. This was not a decision forced on me by the school administration, it was simply what i felt was best for our club membership. Many of the kids were disappointed by this decision, but others were happy because this would allow them to be involved again. I had also begun to feel that the material itself would be better served if I were to stage American Idiot _unedited_ with another local organization, and encourage the families who still wanted to do the show to become involved with it there.

My decision to change the show came prior to finalizing the contract and payment, prior to any rehearsal, and prior to casting or auditions. As with any show that would require edits for a high school group, I had a full list of changes that I felt were necessary to the dialogue, and they would have had to meet approval by the publisher. I made several phone calls to MTI during the past year, and their staff were extremely helpful in explaining the procedures for requesting edits.

I stand by my decision to change our choice of production, and I have always felt that the school administration has been supportive of our efforts.

That being said, I am elated that people like yourself are fighting for the freedom of thought and expression that is so vital to the arts. Your coverage of our situation has helped to shed light on the issue, and to spark serious discussion in our community. Mr. Armstrong’s support has likewise invigorated our students. Although we will not be performing American Idiot for our end of year production, you can be sure that the Lamplighters will continue to push boundaries and explore serious issues.

Thanks again,

Nate Ferreira

Director, Enfield Lamplighters

This post will be updated as additional information becomes available.

Thanks to the National Coalition Against Censorship, which first became aware of this situation and brought it to my attention.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts

December 22nd, 2015 § § permalink

Jonathan Larson’s Rent at PACT in Tullahoma TN (photo by Howard Sherman)

I honestly wish I could figure out what makes one blog post a roaring success, and another a blip on the radar. Certainly the topic under discussion has some impact, but readership seems just as likely to be affected by the title, a photo, the Facebook algorithm, the timing of a tweet, what else is happening in the world, and so on. In short, I have no idea.

In looking over my most-read posts of 2015, I do know which ones took a great deal of research and time, and which were dashed off in under an hour. I know which ones were written after a great deal of consideration, and which were wholly reactive to something I read or heard. They don’t necessarily correlate to readership at all.

I am surprised by the way in which my most-read posts were grouped in the latter half of the year, with seven coming since October 29. Is there any correlation with the fact that I began regularly working out of The New School Drama offices starting in early October, in my new role as director of the Arts Integrity Initiative? I think it’s just coincidence, but it’s possible that the new environment meshed with some significant incidents to yield my most successful writing.

While it may seem paradoxical to offer up my most-read work once again, I have no doubt that there are plenty of people who didn’t read one or more of these when they were first posted, and perhaps there are a few people who would like to catch up with them now. You’ll note I’m not providing them in order of popularity, because it’s not a contest, but I can say that even within these ten, there’s a differential of some 10,000 views.

* * *

July 3: Preparing For Anti-“Rent” Messages From Tennessee Pulpits

I had spoken with the leadership of the PACT community theatre in Tullahoma, Tennessee when they first began experiencing resistance to their production of Rent, but they decided that they’d prefer to try to address the opposition on a local basis. But ten days before performances were to begin, they learned of a letter in opposition to the show that was being circulated to the local clergy, and felt it was time for me to take up their cause and make it a national issue. I traveled to Tullahoma for the opening night, where I was welcomed by numerous members of the community, including the mayor, but the opposition had failed and the show played to an enthusiastic crowd. A prayer circle outside the theatre, in quiet protest of the production, drew only four people, including the two pastors who had been most opposed to the show.

August 1: Disrespecting Playwrights And Their Words with Young Players in

Minnesota

Words Players Theatre found itself in the midst of a firestorm when several bog posts, mine among them, questioned their practice of soliciting plays for production with their teen actors, but saying that the director had the final word over the show, contrary to the tenets of The Dramatists Guild. I stand by what I wrote at the time, but I was troubled by the degree of vehemence that some directed at the company, which didn’t necessarily seems the best way to educate students, their parents and the company’s leadership about respect for scripts in production. I ultimately wrote a second post, trying to walk back some of the rhetoric that surrounded this situation, not just mine, by the way.

September 15: Putting On Yellowface For The Holidays With Gilbert & Sullivan & NYU

I was far from the only person to speak out against the archaic, stereotypical use of yellowface in a production of the New York Gilbert and Sullivan Players production of The Mikado, but I was among the first, with my blog post going online alongside two others on Tuesday, September 15. The groundswell of reaction grew very quickly in subsequent days, and advocates against the practice of yellowface awoke three days later to find, with great surprise, that the production had been canceled. NYGASP says they will return with a reconceived Mikado that’s appropriate to 21st century America. Perhaps I’ll be writing about that in 2016.

October 29: When A White Actor Goes To “The Mountaintop”

It took three weeks after the production closed for word of Katori Hall’s Olivier Award-winning play being produced with a white actor as Martin Luther King to find its way to general awareness, but once it did, it brought great scrutiny to this production, at a community theatre based out of Kent State University’s Department of Pan-African Studies. What was even more remarkable, and remains still less known, is that the concept of having white and black actors each do four performances as Dr. King never happened – the white actor played the role for the entire run.

November 1: She Has A Name: Casually Diminishing Women In Theatre

I wasn’t exactly mystified as to why an interview with Pam MacKinnon carried a headline that mention her collaborators Al Pacino and David Mamet, both more famous, but it didn’t seem right that the person the paper actually spoke with was subordinated in this way. Intriguingly, not long after I posted my piece, the headline was altered, removing Mamet and Pacino – but it still didn’t mention MacKinnon by name. I was intrigued to discover that in coming up with a headline, I had birthed a Twitter hashtag: #SheHasAName.

November 2: A Seattle Theatre Critic Flies Past An Ethical Boundary

Critic offers his extra complimentary press ticket for sale, via the personals section. This one pretty much wrote itself. But I have to say that I quickly came to regret the tone of this piece, because I let myself succumb to snark precisely because it was so easy in this case. I should have stuck to the facts and let the story speak for itself. My feelings about what this critic did (or tried to do) haven’t changed, but I should have done better.

November 13: Erasing Race On Stage At Clarion University

Coming on the heels of the Mountaintop situation at Kent State, this dispute over racial representation in a college production of Jesus In India at Clarion University led to playwright Lloyd Suh pulling the rights to the show. There was a backlash against Suh from those who didn’t understand, or didn’t wish to understand, what it means to have white actors, even students, playing characters of color. Statements from university figures to the press only fed the uproar. But it has led to multiple offline conversations between Suh and the professor who was directing the show, and between the professor and me as well. Suh and I will be visiting the KCACTF Region 2 festival in a few weeks where we’ll meet for the first time and discuss the issue with the college students and their professors in attendance.

December 2: What Is Being Taught About The Director-Playwright Relationship?

After the heated dialogues that both The Mountaintop and Jesus in India engendered, on social media, in comments sections and in direct correspondence, I was moved to wonder aloud about how the playwright-director dynamic was being addressed in college training programs, both undergraduate and graduate. It prompted yet more comments and e-mails, and frankly helped me to learn a great deal more and provide the basis for further exploration. The post became the basis for a panel added to the KCACTF Region 3 festival, and I’ll be headed to Milwaukee to participate in the conversation right after the first of the year.

December 3: What Does “Hamilton” Tell Us About Race In Casting?

With Hamilton being cited as a reason why white actors should be permitted to play characters of color, I took the opportunity of a previously scheduled and wholly unrelated interview to ask the show’s writer-composer-star Lin-Manuel Miranda for his take on race on stage, both in his own work and the work of others. He was, as always, thoughtful and eloquent, during his dinner break on a two-show day.

December 9: Black Magic Crosses Directing & Design Line in Connecticut

When a community/semi-professional theatre in Connecticut staged a production that looked startlingly like a professional production that had been stage nearby three years earlier, it was an opportunity to address the issue of appropriation from other productions and what constitutes originality in directing and design. While the company in question suspended performances within 24 hours, and have subsequently restaged the show on a new set, the outpouring of anecdotes (and expressions of frustration) about productions that have slavishly copied others came pouring out. I expect to write more on this subject.

* * *

October 16: When A Facebook Comment Says More Than a Long Blog Post About Diversity

While it didn’t make the list of my ten most read posts, top on my list of posts that I wish had been more widely read is this one. Written on a day when a combination of medications for an infection laid me low and found me laying on my sofa most of the day, an array of tweets and comments roused me to string together a few sentences which were probably my only coherent thoughts until the drugs wore off. Even if you don’t read the whole post, take a look at the italicized midsection, which is what I actually wrote that day; the rest is subsequent framing.

June 9: If The Arts Were Reported Like Sports

Truth be told, this was one of my ten most read posts of 2015, but that has little to do with what I actually wrote and everything to do with the video I’d discovered and embedded, once again with framing material that isn’t essential to enjoying the video. My greatest contribution was a snappy title. But if you haven’t seen it and need a laugh at year end, this vid’s for you.

* * *

My thanks to everyone who read, commented, shared, tweeted or wrote to me in connection with my writing this year, and special thanks to those who brought situations to my attention so that I could explore them and share them even more broadly. You all have my very best wishes for a safe, happy, arts-filled 2016.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts and interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts.

December 2nd, 2015 § § permalink

Jonathan Larson’s Rent at Eastern Tennessee State University (Photo by Larry Smith)

I assume most people, either as a child heard, or as a parent deployed, the timeworn phrase, “If someone told you to jump off the Brooklyn Bridge, would you do it?” My parents had a variant along the same lines: “Just because other people do it doesn’t make it right.”

I am reminded of this phrase as it seems every week lately I hear about another instance of a theatre director altering a script or overriding an author’s clear intent; the recent run of examples has been with college-affiliated productions. I wonder whether the people responsible have had others set the wrong example, and they felt they could just join in, or if they just started doing it and, since they were never challenged or caught, kept it up.

The most prominent incidents have been with Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop, at a community theatre affiliated with Kent State University’s Department of Pan-African Studies, and with Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India at Clarion University. In both of those cases, the issue was the casting of roles written as characters of color.

In a markedly less fraught situation which didn’t generate any major headlines, a production of Rent at Eastern Tennessee State University, just before Thanksgiving, had to cancel one day of a five-day run because the show’s licensing house learned of a scene that had been cut without approval. The lost day was used to restore the scene in question, as reported by the campus newspaper, The East Tennessean.

In its coverage, the paper quoted Patrick Cronin, the production’s director and the Program Director of Communication and Performance at the school, as to what had taken place.

“I have directed hundreds of shows, and made many cuts before,” Cronin said. “So, I did the same with the street scenes [in ‘Rent’] because we did not have enough actors to make those scenes interesting.”

At the end of the article, Cronin was again quoted:

“I have a young cast who were able to add six pages of material in two days,” Cronin said. “I am just grateful that we got the show on and that we caught the mistake I had made.”

While the school paper didn’t draw attention to the inconsistency, it’s worth noting that Cronin said that what he did was a mistake, but earlier on he had said it was consistent with what he’d done numerous times before. Secondly, it’s not Cronin who caught the mistake, but someone at the school familiar enough with what had been taking place in the rehearsal room – and with copyright and licensing law – to contact Music Theatre International and give them a heads up about the unauthorized alteration. Finally, isn’t it interesting to note that a solution was found to the supposedly problematic scene, in almost no time at all.

Some might accuse me of conflating the first two examples, which turn on the issue of race in casting, with the third, which was the excision of a scene. But I’d argue that they’re all of a piece, because they involve directors either misinterpreting works or placing their own sensibility above that of the author, be it for practical, aesthetic or intellectual reasons. While I don’t have press reports I can bring forward, I can say that since I began writing on this topic, I have been told numerous anecdotes about shows in academic settings that have been altered for any number of reasons, all without approval.

So I have to wonder: are some theatre programs and theatrical groups at the college level advancing the belief that scripts can be altered at will, or elements ignored? Are schools teaching both the legal and ethical implications of artists’ rights and copyright law, not just to playwrights but to all of those who study theatre? Have bad practices begotten yet further bad practices? Are there professors and program directors who believe that anything produced on a campus falls under the fair use exemption for educational purposes under the copyright laws?

Lest anyone think I’m advocating for slavish recreations of original productions or less than fruitful collaborations on new works, I should state that I most assuredly am not. I want to see directors, whether students or faculty (and, for that matter, professionals as well), have the opportunity to undertake creative productions that will challenge the artists involved and the audiences they attract. I want to see works reinvented, but in ways which reveal something new that is supported by the text, rather than overriding it. That said, I am troubled by a sense that in some cases (I’m not saying that this applies to every production at every school) something approaching film’s auteur theory, in which the director of a movie is seen as its primary author, is filtering into theatre at the pre-professional level in a way which diminishes or disregards the importance and rights of authors.

I have a genuine desire to know the answers to some of the questions I’ve asked above. I’d be interested in those answers not only from faculty but from students both past and present. What is being taught about the relationship between playwright and director, regardless of whether the latter is present in rehearsals, available via computer or phone, otherwise engaged, or even dead but still protected by copyright? I ask because I think we all have a lot to learn. I’d like to hear from you, either on the record or confidentially; you can write to me here.

Oh, since I started with timeworn phrases, let me finish with one as well, which believe it or not I’ve heard more than a few times over my career: “Better to ask for forgiveness than to ask for permission.” These are not, I hope you’ll agree, words to live by. Even if some seem to.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

December 2nd, 2015 § § permalink

Jonathan Larson’s Rent at Eastern Tennessee State University (Photo by Larry Smith)

I assume most people, either as a child heard, or as a parent deployed, the timeworn phrase, “If someone told you to jump off the Brooklyn Bridge, would you do it?” My parents had a variant along the same lines: “Just because other people do it doesn’t make it right.”

I am reminded of this phrase as it seems every week lately I hear about another instance of a theatre director altering a script or overriding an author’s clear intent; the recent run of examples has been with college-affiliated productions. I wonder whether the people responsible have had others set the wrong example, and they felt they could just join in, or if they just started doing it and, since they were never challenged or caught, kept it up.

The most prominent incidents have been with Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop, at a community theatre affiliated with Kent State University’s Department of Pan-African Studies, and with Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India at Clarion University. In both of those cases, the issue was the casting of roles written as characters of color.

In a markedly less fraught situation which didn’t generate any major headlines, a production of Rent at Eastern Tennessee State University, just before Thanksgiving, had to cancel one day of a five-day run because the show’s licensing house learned of a scene that had been cut without approval. The lost day was used to restore the scene in question, as reported by the campus newspaper, The East Tennessean.

In its coverage, the paper quoted Patrick Cronin, the production’s director and the Program Director of Communication and Performance at the school, as to what had taken place.

“I have directed hundreds of shows, and made many cuts before,” Cronin said. “So, I did the same with the street scenes [in ‘Rent’] because we did not have enough actors to make those scenes interesting.”

At the end of the article, Cronin was again quoted:

“I have a young cast who were able to add six pages of material in two days,” Cronin said. “I am just grateful that we got the show on and that we caught the mistake I had made.”

While the school paper didn’t draw attention to the inconsistency, it’s worth noting that Cronin said that what he did was a mistake, but earlier on he had said it was consistent with what he’d done numerous times before. Secondly, it’s not Cronin who caught the mistake, but someone at the school familiar enough with what had been taking place in the rehearsal room – and with copyright and licensing law – to contact Music Theatre International and give them a heads up about the unauthorized alteration. Finally, isn’t it interesting to note that a solution was found to the supposedly problematic scene, in almost no time at all.

Some might accuse me of conflating the first two examples, which turn on the issue of race in casting, with the third, which was the excision of a scene. But I’d argue that they’re all of a piece, because they involve directors either misinterpreting works or placing their own sensibility above that of the author, be it for practical, aesthetic or intellectual reasons. While I don’t have press reports I can bring forward, I can say that since I began writing on this topic, I have been told numerous anecdotes about shows in academic settings that have been altered for any number of reasons, all without approval.

So I have to wonder: are some theatre programs and theatrical groups at the college level advancing the belief that scripts can be altered at will, or elements ignored? Are schools teaching both the legal and ethical implications of artists’ rights and copyright law, not just to playwrights but to all of those who study theatre? Have bad practices begotten yet further bad practices? Are there professors and program directors who believe that anything produced on a campus falls under the fair use exemption for educational purposes under the copyright laws?

Lest anyone think I’m advocating for slavish recreations of original productions or less than fruitful collaborations on new works, I should state that I most assuredly am not. I want to see directors, whether students or faculty (and, for that matter, professionals as well), have the opportunity to undertake creative productions that will challenge the artists involved and the audiences they attract. I want to see works reinvented, but in ways which reveal something new that is supported by the text, rather than overriding it. That said, I am troubled by a sense that in some cases (I’m not saying that this applies to every production at every school) something approaching film’s auteur theory, in which the director of a movie is seen as its primary author, is filtering into theatre at the pre-professional level in a way which diminishes or disregards the importance and rights of authors.

I have a genuine desire to know the answers to some of the questions I’ve asked above. I’d be interested in those answers not only from faculty but from students both past and present. What is being taught about the relationship between playwright and director, regardless of whether the latter is present in rehearsals, available via computer or phone, otherwise engaged, or even dead but still protected by copyright? I ask because I think we all have a lot to learn. I’d like to hear from you, either on the record or confidentially; you can write to me here.

Oh, since I started with timeworn phrases, let me finish with one as well, which believe it or not I’ve heard more than a few times over my career: “Better to ask for forgiveness than to ask for permission.” These are not, I hope you’ll agree, words to live by. Even if some seem to.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

November 20th, 2015 § § permalink

The Bad Seed at Portage High School (Photo by Sarah Farthing-Hudson)

I am delighted to report that all of the smoking, drinking, drugging and sexual references will be intact – tonight, tomorrow and Sunday – in the production of Maxwell Anderson’s 1950s psychodrama The Bad Seed at Portage High School in northwestern Indiana. This may seem entirely unremarkable, except that just 11 days ago, students were still being instructed to strike out lines in their scripts and change stage directions to purge the production of all such content. Even the presence of an ashtray wasn’t going to be permitted.

Mind you, I’m not specifically celebrating cigarette smoking, drug use, alcohol consumption or sexual activities among teens, but rather their ability to portray these activities in a script some six decades old. More importantly, I want to congratulate the students for responding in the best possible– and effective – way when they were instructed to censor the script, knowing full well that no approval had been sought from the licensing house or the author’s estate.

I caught wind of this situation last Wednesday morning, when NWI Times published a story about Portage Thespians appearing at a school board meeting the night before, to express their dismay over the editing they had been instructed to undertake. Per the newtimes.com account, the school board chair professed to know nothing about any censorship, and she asked the superintendent to investigate.

I received the article via Facebook within an hour of it appearing online in Indiana, and I quickly undertook to track down the students who had so responsibly brought the issue to the school board. By noontime, after some social media searching, I was in communication with several students who had been part of the appeal at the board meeting. I quickly learned that the school superintendent had asked to meet with the students after school that very day. I offered some general counsel about broaching the subject at that meeting, and then simply waited for a report as to how things were proceeding.

The Bad Seed at Portage High School (Photo by Sarah Farthing-Hudson)

Imagine my surprise when, just a few hours later, I learned from the students online that The Bad Seed would be performed intact. Students tweeted happily about erasing crossed out lines from their scripts. All was well. The next day, the nwitimes confirmed the news in a followup story.

When situations like this arise at other schools in the future, those committed to the ethically and legally correct path of producing plays as written would do well to remember the words of Portage superintendent. “The director is encouraged to do the show and given the support to use his best judgment to do what is right for the students,” wrote superintendent Richard Weigel once the situation was resolved. He’d already said, in a statement, “From my perspective, the purpose of theater is to provide insights into characters that reflect different ways of thinking. Theater provides an opportunity for our students to reflect on those characters, not become those characters.”

More importantly, people should emulate students like Lydia Gerike, Sara Dailey and Valerie Plinovich (all named by the NWI Times), who spoke out with clarity and integrity in support of the play and their exploration of it. They didn’t need any coaching from anyone, it seems. They knew just what to do to put the situation right.

Mind you, it’s never come entirely clear who demanded the changes to the script, but it seems reasonably safe to assume that it happened somewhere above the drama program’s director and below the level of the superintendent. Infer what you will about who in the school hierarchy might have been behind the effort.

Calm, rational, righteous heads set thing right in Portage, so that homicidal Rhoda Penmark can wreak havoc tonight, tomorrow night and at Sunday’s matinee. I applaud the Portage Thespians from afar. I may not have occasion to be in touch with any of them again. But they deserve credit, along with their superintendent and school board, for making sure things happened as they should, with the play performed as written and students freed to explore characters and habits not necessarily their own. Now all of those involved just need to keep their eyes open for any subsequent homogenization of Portage High School productions, to make sure that the censorship doesn’t happen before future plays are chosen, and the unknown bad seed in this censorship story doesn’t succeed in the long run by foisting bland material on the next wave of shows and students.

So the only thing left to say to the Portage Thespians, as is only appropriate for a show like The Bad Seed, is: knock ‘em dead, kids.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts School of Drama.

November 17th, 2015 § § permalink

“I come at this more like a lawyer, who would say that everybody has a right to a fair trial. Or a journalist, or a priest, who would hear the confession.”

– Anna Deavere Smith

On November 7, I had the opportunity to interview Anna Deavere Smith as part of the third annual “Stage The Change: Theatre As A Social Voice” conference, a day-long event of panels and workshops for high school and college students, a collaboration between the Happauge Public Schools and The Tilles Center at LIU Post. Smith is the creator and performer of such acclaimed “documentary theatre” works as Fires in the Mirror, Twilight: Los Angeles 1992, and Let Me Down Easy. What follows is an edited and somewhat condensed portion of that conversation, aimed at the students in attendance.

HOWARD SHERMAN: No one typically has their own theater: you have to find a place to perform, to convince people to let you do this work. How did you create opportunities for yourself originally?

Anna Deavere Smith at LIU Post

ANNA DEAVERE SMITH: I was really trying to learn some things, which is what started me interviewing people in New York in 1980. Just people I saw on the street, or people I saw like the lifeguard where I swam. Then I paired actors with people. So the first one of these that I made had an actor for each person. I just rented a loft in downtown in Tribeca before Tribeca was hip. It was just broken down, sort of old factories, and abandoned places. There were these lofts that were put together with empty spaces with wooden floors. That was the first one that I made. I made it by charging actors to take a workshop and they would perform as a result of the workshop, but really it was just enough to cover the cost. I don’t know if actors are still like that, but people are always looking for someway to perform.

HES: Was the initial work about exploring characters or subjects?

ADS: It was just characters.

HES: How long do you take to interview people when you’re working on a piece?

ADS: It depends on the piece. The piece that I’m working on now is about young people, younger than you all, that don’t make it through school. And they end up in the criminal justice system. I started working on that in 2013, but I’ve spent maybe a total of three months, spread out, and I’ve done about 150 interviews to start working on that play. It’s called Notes From The Field: Doing Time in Education. For Let Me Down Easy, I interviewed over 300 people, on three continents, so it took some time, but in the middle of that time, I was occasionally doing more performances and gathering more information as I refined the play.

HES: When you moved from characters to subjects, what galvanized you to shifting the work towards something topical?

ADS: What happened was, I really didn’t have a place to do this in the theater. No theater hired me well into the process. Who did hire me was universities, who in the 1980’s were revising many things about their curriculum, mostly to make more space for literature, ideas, works of art by people of different colors than white – of women, as well as people of different expressions of sexuality than heterosexuality. So I would say that in the 1980’s, across the board in this country what we call the canon, what is the traditional thing we learn, changed dramatically. The conservatory, the playwrights were looking at scripts by either dead or living white males and even someone like a white male like Sam Shepard, and even his work was considered extremely avant-garde. The only woman you would find is Lillian Hellman. You know, maybe Lorraine Hansberry.

The ‘80’s were the time where that really shook up, but what that meant was, that at these universities and at these colleges people were very refined, Smith College, a place like that, or Princeton, there were very, very difficult things about people getting along on campus. I was hired by Princeton to write a piece about the fact that they had only had women for 20 years. Think of the history of Princeton. Princeton exists long enough that men from the South brought their slaves to school with them for a very, very long time. These traditions are very hard to change. So 20 years of women, they asked me to come and make a piece. There were some very difficult things happening on campus, some women had had some sexual assaults and yet the alumni, didn’t want to make the lamps any brighter because they felt it would kill the romance of the campus. Two of the eating clubs – they didn’t have fraternities – still would not accept women. After that, they were forced to do so. Places hired me and it was really to mirror them in transition, to mirror back to them the difficulty they were having in transition. There were a group of women professors in the theater across the country having to deal with new things going on among women or even the fight women were having getting into university. That’s what really made my work become socially oriented.

HES: Why the choice to move from bringing in actors to portray each of these people? Why the choice to have these people, instead of having different people play these different roles, to take them all into yourself?

ADS: Again, it was a very practical reason. I couldn’t imagine how to pay everyone. The first time I got away with it because people were so eager to have a reason to perform. They were like me, they were hardly ever getting cast, they were happy to have a reason to have agents and other people come and see them, and to be working. So they paid me to do a workshop and put that together. So I figured that’s not going to work very long. The notion of getting a grant was way out of my – I couldn’t do that.

But then I remembered that as a kid, I was a mimic. So I thought, well I’ll just do all the parts myself, until I can figure out how to raise money. Then when I could figure out how to raise money, and invited actors to do it, they didn’t really like my process. I think it would be different now. This whole idea of documentary theater, it’s taken off in a big way. When I first started presenting the work to actors, they didn’t like it because they felt so much of the idea of acting training, and maybe these young people today have this idea and maybe not, was the idea of inner truth.

I don’t believe my inner truth is necessarily relevant to the cowboy you saw there [in a video screened at the event]. I’m trying to figure out his inner truth! Things that I’ve learned about language have lead me to understand and believe, and try to exemplify, is that his inner truth, whether he’s telling the truth or not, does live in how he sees. So I’m not into this inner truth stuff. I don’t like the word truth. That’s a moral judgment and it’s a very heavy idea. In those days, I’ve always taught acting since 1973, you know we have these students who would go to conservatory to hear notes from all these teachers. My colleagues would do stuff like yell at people for acting. “You’re lying!” Of course they’re lying, they’re acting.

HES: When actors play roles that aren’t necessarily likable or honest, you often hear the talk about finding some part of them to like. Do you need to like the people and do you even like the people you end up interviewing?

ADS: Well, I love everybody I interview. In my Ted talk, I performed a woman who sat on her bedside while her boyfriend killed her daughter. Murder, that’s murder, she’s an accomplice to murder. And I met her in a penitentiary in Maryland. I come at this more like a lawyer who would say that everybody has a right to a fair trial. Or a journalist, or a priest, who would hear the confession, most likely of the person who did the most despicable thing. And I think of people in terms of their fate in life.

Anna Deavere Smith at LIU Post

I think a person who does a very despicable thing like the women who let her child be killed is trapped not only in prison but in her own crisis of what she did when she recognizes what she did, when she sees that reality. And so I think I have a bit of humility about these things. I do believe that in the grace of God, I do believe in old fashion acting techniques, Stanislavski, the father of modern acting, way back in the 19th century. People behave according to their circumstances and how they adjust to those circumstances.

So I don’t know what it would be like for me to live in an environment where I was acquiring drugs, selling drugs, addicted to drugs, was in a relationship with a man who beat me, beat my children, and for whatever reason I learned to understand that as normal. And that would lead me to be so high that I would allow that to happen to my child. My job is to imagine those circumstances and then to find a way to illuminate that for whatever reason.

Maybe the thing I would be trying to illuminate is drug addiction. Maybe I would be trying to illuminate what it does mean for women to live in abusive relationships, right? So I see that person as living a life that is at first unimaginable to me, and then my job is to imagine it. I think as actors, we have chance to do big projects like that. If I were a doctor, I could choose, am I going to be an internist? Am I going to want to do big operations? Am I going to be a surgeon of cancer? You know, I could choose how big I want my project to be. I do think the project of portraying someone who seems to be unlikable, or you know if you meet somebody in your school whose perfectly likable, a cheerleader, but you don’t like her, then the project is how do I get myself to be able to imagine her circumstances and to imagine living in her shoes? Then my project is really living in their words. For me, again, the bigger the project, the better, the bigger leap I have to make, the more I get to exercise my muscles as an artist.

HES: When you set out to do a project, do you always know exactly what you want to explore? Or do you start having conversations and find the subject or the focus that you’re going to take on it?

ADS: I don’t have a take, and my take evolves. For example, my new project is about what some people call the school to prison pipeline. I don’t know if you’ve heard about this at all or you’re starting to hear about it, I started to hear about in 2011, and I’d never heard about it. So the idea is poor kids of color are unfairly disciplined, some of you might have seen this video that has kind of gone viral of a girl in South Carolina who won’t turn her cell phone off and then they bring the cop in and he throws her around in the chair. We see these things.

Say, for example, I started out, with the idea of images in my mind like hearing about a five year old in Florida who was handcuffed, this kind of thing. But the more I looked at it, the more I see that the thing that causes young people to end up in juvenile hall or in these kinds of circumstances are even more complicated than school discipline. So now I would never call it the school to prison pipeline. I don’t know quite what I would call it, but I’d call it something else that allows the project to be seen as about a series of things that make it hard for young people to be in our education system.

HES: You are now, of course, widely known in the theater community and many communities for the work that you do. Has it become easier to gain access to people to interview them or are people now more aware of how you might portray them? And does that, in some ways, make people more guarded?

ADS: Well I think most of the people I interview have never heard of me. At all. And if they have, it’s because they saw me on a television show called Nurse Jackie. Maybe.

Anna Deavere Smith in Let Me Down Easy

I am very aware that my theater is in a very small portion of America. That is the kind that these young people are here to think about, work on, theater about social change. It’s not a big Broadway show. Only one of my works went to Broadway. A lot of people don’t know about my theater work. But what has happened, as you know, these young people would certainly, I mean there doing selfies all the time and filming each other all the time, people are much less inhibited, they don’t care anymore. I used to travel with a tape recorder about that size, now you know I can use my phone, now I bring a camera in, nobody cares!

I think as a society – I’ve been doing this for a long time – as a society we’ve changed in terms of our sense of being public. And we sign a release, some of them don’t even look at it. I encourage them to, take your time, cross out anything you don’t like. But I think it’s also because of all of this stuff, reality television. When I started there wasn’t even Oprah, you know what I mean? All these things that make people feel like, ‘Well I’m a star! I’m telling my tale!’

HES: Can theater create social change or does it begin to go back to your word, mirror social change?

ADS: Well I certainly believe it can be a part of sparing the time and I think it rides that wave, it pushes us farther.

I would say that there are many things on television that had to do with change, even the show I was on Nurse Jackie has to do with something in the human condition which is not a movement. But many people on the street came up to me and told me how much the character Jackie meant to them in their recovery from addiction. Tony Kushner did a lot to help us in a time where we were thinking about the AIDS crisis to well before gay marriage and all that. So I think we that are interested in change are not making the change alone at all. But if we are on the moment of trying to expose something that’s going on, and people come to the theater, it gives them an opportunity to look through in a different way than they see in a newspaper. It causes some people’s hearts to be changed and it can be a conversion. It can cause a conversion in terms of behavior for some folks.

HES: You speak to people in all walks of life. And you sometimes speak to really, really important leaders. What is it like to be an artist who has the ability to speak beyond just the work that you create?

ADS: The irony is that all of you are learning how to perform but the kind of performance that you’re doing, if you’re performing on behalf of social change, at some point is indicating to the viewer this is not a show. I’ve called you here because this is real. I’ve called you. I need to catch you attention. You might not have noticed it on the paper. You might not have noticed it on the news. You may not know. You’ve heard people talk about bullying but you may not really, if you don’t have a child, who’s being bullied, you may not really know. So I would like you to, you heard about it for a little bit of time on CNN 360 or something but I would like you to come in here with your whole heart and mind and visit it with me. Right? So there is this way that when you take on social change, it gets real. Right?

So I think that’s the way one ends up in the company of academics, the President of the United States, governors, chief justices, or justices of the supreme court, are many of the kinds of people that I’ve had the chance to speak with. It’s because of that reality and because we are all in those realms trying to address those realities. And luckily there are many government leaders who do see the value of art as one way of causing people to tend to these issues.

HES: You talk about truth, you talk about reality. You talked about journalism. Is what you do a form of documentary?

ADS: Well, people say that. I suppose it has aspects of that. However the part that is not documentary is that it is my persona, not the persona of the persons. So there’s already that other thing going on. So it’s not really a photograph, right? It has been adjusted and altered, so the fact of the aesthetic part of it is relative. I mean I’m not the cowboy, so maybe there’s something interesting about an African American woman older than this cowboy with assumed different political views, maybe there’s another suggestion about the fact that I’m not him. I think that suggestion is about asking the audience to reach outside their own known world to consider the point of view of someone else or the life of someone else.

HES: Is there a way you would suggest to people how they might approach getting to this work for the first time?

ADS: Interview your little sister. You know, interview the lady next door. The main thing is to talk to somebody you’re really curious about and to see what you have to do to get them to talk. Do they become interesting and more interesting than you thought while you were talking to them? I would say that’s a way to start.

HES: And when you interview people, are you just doing audio or are you doing video?

Anna Deavere Smith in The Pipeline Project

ADS: I’m doing video now. I would like to [put it online] largely because, by the time we’re finished with what I call the “Pipeline Project,” I’ll have at least 200 interviews. I’m only going to perform for an hour and a half on stage. Think of all that material that is never seen. Right? Characters. I think the work could be of use to folks who would like to either now or years from now like to look back on this moment in American history and look at this crisis. So that’s why to put the work out there to be of use.

HES: In an age of what you say selfies and social media, where people are so much more exposed and there are people who desire to be exposed, do you want people when they see your work to think that they are seeing you or do you want to be completely behind your character, the people that you play?

ADS: I’d be more concerned that I don’t want them to think that I’m Mrs. Akalitus from Nurse Jackie. I had a student of mine – I teach at NYU – and one of the graduate students told me that his mother had said, “I just saw your professor on television and I thought you said she was intelligent.”

I see my identity as for rent, and I want them to hear what the people have to say. I want them to hear what I heard. But I hope I don’t get in the way of that. I hope that my presence doesn’t get in the way of that but I know that my presence is there.

HES: The Pipeline Project has played out in Berkeley, California. You said to me that it’s going to have a few performances in Baltimore. Do you want it to have more or do you reach a point where you feel like I’ve done this piece?

ADS: I would like this piece to have more because I feel that the people are ever so compelling and that I want to keep refining them. I know more now about how to do these portrayals than I ever had, and that’s what happens to all of us, we gather information. I have that thing like a baby who knows it’s time to crawl. Your mother’s wondering when is he or she going to crawl? When is he going to walk? And they’re walking and that inner urge that we all have as humans, trying to ride a bike, trying to do something. I do have this great feeling to keep doing this project. To keep refining these portrayals. To keep trying to make the lens that I’m using to look at this large enough that it could be of use to the public.

HES: Obviously you go to a lot of different places to conduct your interviews, but you also perform in a number of different places. What is the experience if you know that one or more of the people that you’re portraying is in the house when you’re doing the show?

ADS: I’m nervous about it, I do invite them all. I want them to see it. And you know, I hope that they are not too self conscious or upset. I don’t think people tell me the truth about what they see. But it is important to me that they are invited and that their families are there.

HES: Very often, writers who are writing a conventional script, a writer who is sitting at the computer, creating the story, are sort of going towards wanting you to think something, wanting you to come out with a thing, or a group of things. Do you want people to come away with a particular thing?

ADS: This generation here is probably the first generation in a very long time, certainly in my lifetime, who actually comes to school to look at artistic practice for social change. This is the first time I’ve ever heard of this happening in high school. It’s usually Guys and Dolls or West Side Story or whatever the latest thing is, right? A Chorus Line. You get to be in the show! Right?

There’s always this concern that if you apply yourself like this, that you’re being didactic, or being political, right? So the people running for President want you to think something. ‘I’m the baddest of the bad and I’m the one that you should elect,’ right?

I want people to be driven to action. I want them to write a check to make something better for a kid somewhere. I want them to become involved in early childhood if they can. I want them to think about these kids, [about] who they want to elect as President of the United States. I want them to think about these kids when they decide who the mayor is in their town.

I want them to think differently about a kid who is walking by in the “iconic” hoodie with his pants down quite low in the back, because that’s what I want to consider. These kids who we lock up might not all be as dangerous as we think, in fact they’re very, very vulnerable to some profound inequities in society that make living pretty dangerous where they live. I want people who can do stuff to do stuff even if it’s, ‘I’ll walk a kid to school who has to cross a gang line’ or drive them or whatever. I want people to move up and do things the way that people did things when I grew up in the Civil Rights Movement. It’s that kind of moment in American history where people went outside of their normal doing to do a little bit more. I feel that we are really in a moment in our history where we need that to happen.

* * *

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School for Performing Arts School of Drama. Thanks to Briana Rice for editorial assistance with this post.

November 16th, 2015 § § permalink

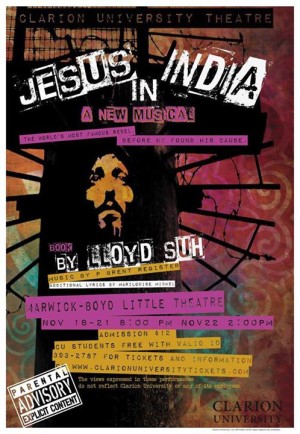

Poster for Jesus in India at Clarion University

“What will you learn?” asks the home page of the website of Clarion University in Pennsylvania. In the wake of the school’s handling of the casting of white students in Asian roles in Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India, and the playwright’s withdrawal of production rights upon learning this fact, it’s unclear at best, disturbing at worst, to consider what Clarion wants students to learn about race and about the arts.

Based on what is appearing in the press, they are learning to blame artists for wanting to see their work represented accurately. They are learning to attack artists when the artists defend their work. They are learning that a desire to see race portrayed with authenticity is irrelevant in an academic setting. They are learning that Clarion seems unaware of the issues that have fueled racial unrest on campuses around the country, most recently with flashpoints at the University of Missouri and Yale University. They are learning that when a community is overwhelmingly white, concerns about race aren’t perceived as valid.

In an essay published in the Chronicle of Higher Education on Friday, Marilouise Michel, professor of theatre and director of the canceled production, wrote, “I have intentionally left out the name of the playwright and the piece that we were working on as I do not wish to provide him with publicity at the expense of the fine and viable work of our students.” What’s peculiar about that statement is that until 1:30 pm that day, when he released a statement, the playwright hadn’t sought for this issue to be public in any way. It was Clarion that had contacted the press, Clarion which had released his correspondence with Michel, and Clarion which used a professional public relations firm to issue a statement about the situation from the university and its president. It reads, in part:

The university claims their intent from the start was to honor the integrity of the playwright’s work, and the contract for performance rights did not specify ethnically appropriate casting. Despite the university’s attempt to give Suh a page in the program to explain his casting objections and a stage speech given by a university representative on the cast’s race, Suh rejected any solutions other then removing the non-Asian actors or canceling the production.

“We have no further desire to engage with Mr. Suh, the playwright, as he made his position on race to our theater students crystal clear,” says Dr. Karen Whitney, Clarion University President. “I personally prefer to invest my energy into explaining to the student actors, stage crew and production team members why the hundreds of hours they committed to bringing ‘Jesus in India’ to our stage and community has been denied since they are the wrong skin color

This insidious inversion of racial justice is profoundly troubling. The play, set in India, has three characters named “Gopal,” “Mahari/Mary,” and “Sushil,” a strong indication of their race. Suh maintains that the university was asked about their plans to cast those roles, and his agent Beth Blickers says no answer was ever given. But when the playwright finally drew a line over racial representation, he was the one who was supposedly denying skin color, when it was Michael’s personal interpretation of the play, against clear evidence and requests, which was ignoring race in the play. So now, one must wonder whether Dr. Whitney will be spending time explaining to the students of color on campus why she is vigorously defending the practice of “brownface” on campus (white actors portraying Indian characters, regardless of whether color makeup is actually employed) and attacking a playwright of color for decrying the practice.

To be clear, there is undoubtedly great disappointment and pain among the students and crew who had been working on the production. Anyone in the arts will surely sympathize with them for having invested time and effort towards a production that they surely undertook with the best of intentions. But they were, most likely unwittingly, made complicit in the act of denying race and denying an artist’s wishes.

In the university’s press release, the extremely small Asian population of the school is noted (at 0.6% of the student body), as it has been previously in many reports. That no Asian students auditioned should not have been surprising, nor should it have been license to substitute actors of others races as a result. Any director who is part of an academic theatre program has a very good idea of what talent may be available, and often productions are chosen accordingly. So it is not the failure of Asian students to audition to blame for the inaccurate racial casting. More correctly it was the decision to produce a play which clearly called for Asian characters and the assessment that race didn’t matter that created this situation – not Lloyd Suh or any student.

In the Chronicle, Harvey Young, chair of the theatre department at Northwestern University, admittedly a more urban school, says the following regarding racial casting on campus:

“That is the magic of the university — to introduce people to a variety of perspectives and points of view.”

But at Northwestern, Mr. Young said, the department uses a variety of strategies to avoid what could be racially problematic casting. The department has hired outside actors to play some roles and serve as mentors to students, reached out to minority groups to let them know about acting opportunities, and staged readings at which only voices are represented.

“The goal is to devise strategies that allow you to engage the work while being aware of whatever limits exist,” Mr. Young said.

In her essay for the Chronicle, Michel wrote, “Perhaps Shakespeare would wince at a Western-style production of The Taming of the Shrew, but he never told us we couldn’t. He never said Petruchio couldn’t be black, as he was in the 1990 Delacorte Theater production starring Morgan Freeman.” This is a specious and rather ridiculous argument, since Shakespeare’s work is not under copyright and can be cast or altered in any way one wishes. While there are certainly examples of actors of color taking on roles written for or traditionally played by white actors – NAATCO’s recent Awake and Sing with an all-Asian cast playing Clifford Odets’s Jewish family, the Broadway revival of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof with a black cast playing Tennessee Williams’s wealthy southern family – they were done with the express approval of the rights holders. That these productions were in New York as opposed to Clarion, Pennsylvania makes no difference as to the author’s rights. What we have not seen is an all-white Raisin in the Sun, either because no one has been foolish enough to attempt it or because the Lorraine Hansberry estate hasn’t allowed it.

Clarion’s press efforts have certainly paid off in the local community, with three news/feature stories in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (here, here and here) as well as an editorial, along with two features (here and here) in the Chronicle of Higher Education, in addition to the aforementioned essay. That the Post-Gazette’s editorial sides entirely with Clarion is no surprise, since the university was driving the story; that it fails to take into account any reporting which runs counter to Clarion’s narrative, and indeed repeats them, is shameful, a disservice to the Pittsburgh community. That the Chronicle of Higher Education ran Professor Michel’s essay, another one-sided account of the situation, is problematic, but the headline (whether it is theirs or Michel’s), “How Racial Politics Hurt My Students,” is a clarion call for paranoia about race. It ignores the fact that the problems arose from a failure to respect the work and the playwright, that the issue is based not in politics, but in art, and that the author saw his work being defaced and stood up for it. There have been countless other reports on the situation. That this has engendered vile racist outpourings online, especially in comments sections and on Facebook, and in some press accounts is the result of the university’s irresponsible spin.

Universities are in no way exempted from professional standards when it comes to licensing and producing shows; to claim otherwise is to suggest that campuses are bubbles in which the rules of the real world do not apply. While classrooms are absolutely places for exploration and discovery, theatre productions of complete works for audiences are not just educational exercises. Students need to be taught creative and legal responsibility towards plays (and musicals) and their authors, not encouraged to take scripts as mere suggestions to be molded in any way a director wishes. When it comes to race, this incident and the recent Kent State production of The Mountaintop will now insure that every playwright who cares about the race of their characters will be extremely explicit in their directions, but that doesn’t excuse directors who look for loopholes to justify willfully ignoring indications in existing texts.

It’s my understanding that there has been new contact between Michel and Suh, though I am not party to its nature or content. It’s worth noting that in the third Post-Gazette story, it is reported that “Ms. Michel took to Facebook Saturday to ask “that any negative or mean-spirited posts or contact towards Mr. Suh be ceased. We are both artists trying to serve a specific community and attacking him helps no one.” That’s a responsible position to take, but it should be expanded to include negative posts or contact about the accurate portrayal of race in theatre, since they are flourishing in the wake of this incident.

It is also now time for the university to explain the truth about why the production was shut down, namely a failure to respect the artistic directive of the playwright; insure that this incident and the rhetoric surrounding it hasn’t been a license for anyone to marginalize their students of color; and begin truly addressing equity and diversity on their campus. Regardless of the racial makeup of their community or student body, they need to be setting an example and creating a better environment for all students, not feeding into narratives of racial divisiveness.

Update, November 18, 7 pm: Earlier today, the Dramatists Guild of America released a statement regarding the organization’s position on casting and copyright, signed by Guild president Doug Wright. It reads, in part:

One may agree or disagree with the views of a particular writer, but not with his or her autonomy over the play. Nor should writers be vilified or demonized for exercising it. This is entirely within well-established theatrical tradition; what’s more, it is what the law requires and basic professional courtesy demands.

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts School of Drama.

November 16th, 2015 § § permalink

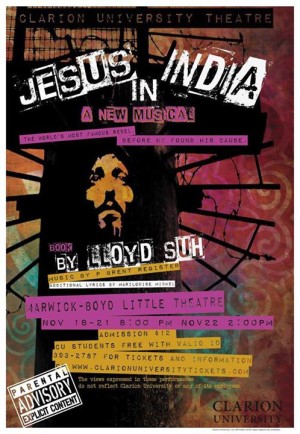

Poster for Jesus in India at Clarion University

“What will you learn?” asks the home page of the website of Clarion University in Pennsylvania. In the wake of the school’s handling of the casting of white students in Asian roles in Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India, and the playwright’s withdrawal of production rights upon learning this fact, it’s unclear at best, disturbing at worst, to consider what Clarion wants students to learn about race and about the arts.

Based on what is appearing in the press, they are learning to blame artists for wanting to see their work represented accurately. They are learning to attack artists when the artists defend their work. They are learning that a desire to see race portrayed with authenticity is irrelevant in an academic setting. They are learning that Clarion seems unaware of the issues that have fueled racial unrest on campuses around the country, most recently with flashpoints at the University of Missouri and Yale University. They are learning that when a community is overwhelmingly white, concerns about race aren’t perceived as valid.

In an essay published in the Chronicle of Higher Education on Friday, Marilouise Michel, professor of theatre and director of the canceled production, wrote, “I have intentionally left out the name of the playwright and the piece that we were working on as I do not wish to provide him with publicity at the expense of the fine and viable work of our students.” What’s peculiar about that statement is that until 1:30 pm that day, when he released a statement, the playwright hadn’t sought for this issue to be public in any way. It was Clarion that had contacted the press, Clarion which had released his correspondence with Michel, and Clarion which used a professional public relations firm to issue a statement about the situation from the university and its president. It reads, in part:

The university claims their intent from the start was to honor the integrity of the playwright’s work, and the contract for performance rights did not specify ethnically appropriate casting. Despite the university’s attempt to give Suh a page in the program to explain his casting objections and a stage speech given by a university representative on the cast’s race, Suh rejected any solutions other then removing the non-Asian actors or canceling the production.

“We have no further desire to engage with Mr. Suh, the playwright, as he made his position on race to our theater students crystal clear,” says Dr. Karen Whitney, Clarion University President. “I personally prefer to invest my energy into explaining to the student actors, stage crew and production team members why the hundreds of hours they committed to bringing ‘Jesus in India’ to our stage and community has been denied since they are the wrong skin color

This insidious inversion of racial justice is profoundly troubling. The play, set in India, has three characters named “Gopal,” “Mahari/Mary,” and “Sushil,” a strong indication of their race. Suh maintains that the university was asked about their plans to cast those roles, and his agent Beth Blickers says no answer was ever given. But when the playwright finally drew a line over racial representation, he was the one who was supposedly denying skin color, when it was Michael’s personal interpretation of the play, against clear evidence and requests, which was ignoring race in the play. So now, one must wonder whether Dr. Whitney will be spending time explaining to the students of color on campus why she is vigorously defending the practice of “brownface” on campus (white actors portraying Indian characters, regardless of whether color makeup is actually employed) and attacking a playwright of color for decrying the practice.

To be clear, there is undoubtedly great disappointment and pain among the students and crew who had been working on the production. Anyone in the arts will surely sympathize with them for having invested time and effort towards a production that they surely undertook with the best of intentions. But they were, most likely unwittingly, made complicit in the act of denying race and denying an artist’s wishes.

In the university’s press release, the extremely small Asian population of the school is noted (at 0.6% of the student body), as it has been previously in many reports. That no Asian students auditioned should not have been surprising, nor should it have been license to substitute actors of others races as a result. Any director who is part of an academic theatre program has a very good idea of what talent may be available, and often productions are chosen accordingly. So it is not the failure of Asian students to audition to blame for the inaccurate racial casting. More correctly it was the decision to produce a play which clearly called for Asian characters and the assessment that race didn’t matter that created this situation – not Lloyd Suh or any student.

In the Chronicle, Harvey Young, chair of the theatre department at Northwestern University, admittedly a more urban school, says the following regarding racial casting on campus:

“That is the magic of the university — to introduce people to a variety of perspectives and points of view.”

But at Northwestern, Mr. Young said, the department uses a variety of strategies to avoid what could be racially problematic casting. The department has hired outside actors to play some roles and serve as mentors to students, reached out to minority groups to let them know about acting opportunities, and staged readings at which only voices are represented.

“The goal is to devise strategies that allow you to engage the work while being aware of whatever limits exist,” Mr. Young said.

In her essay for the Chronicle, Michel wrote, “Perhaps Shakespeare would wince at a Western-style production of The Taming of the Shrew, but he never told us we couldn’t. He never said Petruchio couldn’t be black, as he was in the 1990 Delacorte Theater production starring Morgan Freeman.” This is a specious and rather ridiculous argument, since Shakespeare’s work is not under copyright and can be cast or altered in any way one wishes. While there are certainly examples of actors of color taking on roles written for or traditionally played by white actors – NAATCO’s recent Awake and Sing with an all-Asian cast playing Clifford Odets’s Jewish family, the Broadway revival of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof with a black cast playing Tennessee Williams’s wealthy southern family – they were done with the express approval of the rights holders. That these productions were in New York as opposed to Clarion, Pennsylvania makes no difference as to the author’s rights. What we have not seen is an all-white Raisin in the Sun, either because no one has been foolish enough to attempt it or because the Lorraine Hansberry estate hasn’t allowed it.