March 29th, 2017 § § permalink

Nora Brigid Monahan in “Diva: Live From Hell” (Photo courtesy of DDPR)

I cannot claim that I was completely surprised. By the same token, I didn’t know exactly what to expect.

A press release first made me aware of Diva: Live From Hell, and I lingered on it longer than most I receive. The plot synopsis, of a high school drama kid doomed to Hell for his thespian transgressions while alive, ticked off some of the boxes that usually interest me, school theatre in particular. But thinking about the already heavy theatergoing schedule I keep in late March and April, I decided I’d better give it a pass. So many shows, so little time.

That was that, until a Facebook message popped up from Morgan Jenness, the highly regarded dramaturg, agent, teacher, literary manager, activist, advisor, artist advocate and so much more. Was I planning to see Diva: Live From Hell, she wondered, because she thought I should see it. I replied, explaining that I’d thought about it, but decided to forego it. She wrote back to say I really should see it, and when Morgan gets emphatic like that, I know I’d be foolish not to take heed. I said that if she felt so strongly, I’d go. So while I began to ponder exactly what the deal was, I made a mental note to look to see when it was playing, having already deleted the press release.

When I awoke Monday morning to a Facebook wall post from Daniel Goldstein, who was directing the show, saying that I “may or may not be name-checked” in Diva: Live From Hell, I understood why Morgan was being so insistent. After all, Daniel couldn’t be posting versions of that message on the pages of all of his Facebook friends as a marketing ruse to sell tickets to the show, could he?

When I awoke Monday morning to a Facebook wall post from Daniel Goldstein, who was directing the show, saying that I “may or may not be name-checked” in Diva: Live From Hell, I understood why Morgan was being so insistent. After all, Daniel couldn’t be posting versions of that message on the pages of all of his Facebook friends as a marketing ruse to sell tickets to the show, could he?

That’s how I found myself at Theatre for the New City on Monday night, with less than eight hours planning, having discovered that given my aforementioned busy schedule and the limited run of Diva, the only possible time I could attend was that same day. Normally, my theatergoing is planned out weeks in advance. Moviegoing is more spur of the moment for me.

So I might get some manner of shout out during the show, but of course I didn’t know when, and I didn’t know what it would be. It’s actually a terrible way to watch a show, waiting for a very specific yet indeterminate moment, but I tried to just relax and enjoy the proceedings. I settled in for the saga of Desmond Channing, played by Nora Brigid Monahan, who had also devised the show and written the book (music and lyrics are by Alexander Sage Oyen). Damned to recount his sordid tale of high school theatre rivalry, Desmond’s eternal cabaret is playing a lounge in the fiery pit; Roy Cohn, he tells us, is playing the big room.

(At this point I should give a lackadaisical spoiler alert, for those who find the prospect of hearing my name in a theatre production utterly thrilling. I imagine that if such a community exists, it’s extremely small, and perhaps might want to seek professional help.)

It wasn’t very far into the show, as Desmond relived his triumphant high school theatre career, that my name came up.

“I mean, I’m sure we all remember last year’s stunning production of “Flower Drum Song.” And not because of the controversy surrounding the casting! I’m still very hurt by Howard Sherman’s letter-writing campaign vilifying me for my portrayal of Wang Chi-Yang.”

OK, there it was. A good-natured ribbing of my advocacy regarding authenticity in racial casting and against practices such as yellowface. The audience laughed, but so far as I could tell, it was with the punchline, not at the mere mention of my name. I settled in to watch the rest of the show.

So imagine my surprise when only a bit later, I heard Desmond say the following:

“Auditions for the Fall Musicale are tomorrow. You just have to sing a Gilbert and Sullivan song. Wait a minute! What should I sing? Maybe “He is an Englishman.” No, everyone’ll do that… Or maybe something from “The Mikado”… No, can’t. Damn that Howard Sherman.”

Wow, I’m a recurring joke, albeit a highly esoteric one. But Monahan wasn’t quite done with me, as I discovered later in the show with the following interjection:

DALLAS: Alright, don’t make a big show. You know you’re the only student I let in the faculty room. Don’t abuse the privilege. Nice Louis Armstrong, by the way. If we hadn’t gotten in so much trouble for “Flower Drum Song,” next year I could’ve cast you as Porgy.

DESMOND: (Under his breath, furious) Sherman…

Because I was engaged in the show itself, my thoughts about these mentions didn’t really come until the lights went out and the curtain call began.

First thought: well, I guess people are registering the kind of advocacy I’ve been doing if it rises to the level of lampooning in an Off-Off-Broadway showcase.

Nora Brigid Monahan in “Diva: Live From Hell”

Second thought: I would never, NEVER, lead a campaign against any high school student. At the high school level, I try to be supportive. I might have had a few words for a teacher so clueless as Mr. Dallas.

Third thought: Wow, I got name-checked alongside Kevin Kline, Tovah Feldshuh and Patti LuPone, among many others. Of course, Seth Rudetsky appeared as himself via recording, a more prominent inclusion in Monahan’s imagined world. (Under my breath, furious) Rudetsky!

As I exited the theatre, I encountered Morgan Jenness, grinning widely, eager to hear what I thought. I said I’d had a good time and was amused to be part of the show. “But, I confided to Morgan, “I don’t think anyone in that theatre had any idea that I’m a real person. I’m just a fictional nemesis invented by Sean along with the other characters.”

“Oh, Howard,” she replied, “People know who you are. And after all, it’s a pretty insider show.”

“Insiders enjoy LuPone and Kline jokes,” I countered. “Mentions of me are downright obscure. As far as this audience knows, I’m a fiction.”

And so, for the next week and half at least, I will have my own form of immortality, embedded in the pages of a theatrical script and spoken aloud for presumably unwitting audiences. This joins my other brushes with exceedingly minor fame, including my guest appearance as a Cupcake Wars judge and my three-sentence role on an episode of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit.

But I thank Nora Monahan for giving me this little gift of recognition, and perhaps someone will see Diva: Live From Hell and laugh spontaneously and knowingly at the mention of my name (if I haven’t already spoiled the moment for those most likely to do so with this essay). And while my next two weeks are completely committed, perhaps I’ll have the chance to encounter Desmond Channing once again, be it in this life, or the afterlife.

August 2nd, 2016 § § permalink

Margaret Hughes

It is quite possible that, when the English stage was officially opened up to allow women to perform alongside men, most likely in 1660 when Margaret Hughes played Desdemona, some argued against it, on the grounds that young boys had been successfully been playing women for years, and if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. After all, only 30 years earlier, a French touring troupe met with disdain for daring to employ women, and even once English women were permitted to act, men did not immediately cease playing women’s roles.

Ira Aldridge

When Ira Aldridge became the first black actor to find fame on the stages of Europe, having left America, which offered him no opportunity, there were at first people who took exception to the breaking of the color line, feeling that blackface had been more than sufficient for the portrayal of non-white characters and that a black man speaking the words of Shakespeare was “blasphemous.” One critic wrote that “with lips so shaped that it is utterly impossible for him to pronounce English,” while another objected to his leading lady being “pawed about on the stage by a black man.”

Phyllis Frelich

After Phyllis Frelich won a Tony Award in 1979 for Children of a Lesser God, might some have dismissed her honor as resulting from a sympathy vote because she was a deaf woman playing a deaf woman, or that her achievement was somehow less simply because she used sign language, which was how she communicated every day? After all, one critic, praising Frelich, took note of her “affiliction.”

Invented scenarios? Only in part. And certainly none are implausible, at distances of hundreds of years or just a few decades. They are, after all, representations of the breaking of a status quo, the altering of a dominant narrative, and the much too easy ways of diminishing significant achievements at the time that they happened.

The stage remains a place where certain practices, steeped in tradition, persist. Despite being seen by many as a bastion of liberals and progressives, the arts are dominated by white Eurocentric men, whether it comes to the stories being told or the people placed in the positions of authority who are charged with making work happen. While the not-for-profit arts community has begun in recent years to explore equity, diversity and inclusion initiatives designed to give voice to a broader range of gender, race, ethnicity and disability, the field is still dominated by white structures and white professionals “opening doors” to other stories.

That’s not to be dismissive of those efforts, but only a means of contextualizing them and reflecting how nascent they still are in so many places. Let’s not forget, it was only in 2015 that the Metropolitan Opera dropped using blackface on the actor playing the title role in Otello, an original Broadway musical featured an all-Asian cast, an actor with a mobility disability in life originated a role in a Broadway production using a wheelchair. How was it possible that this hadn’t happened sooner?

The changes on our stages, the efforts to assert of a broad range of identity where it was previously denied, is reflective of society as a whole. While it has been 51 years since the passage of the Civil Rights Act and 26 years since the passage of the Americans With Disabilities Act, there are still legal battles being fought to insure and protect their full and proper implementation. However, in the past decade, with the rise of social media, advocates for change have had the opportunity to make their cases ever more swiftly and directly, without adjudication by the media as to what concerns will be permitted to reach a critical mass of awareness, with people driving the story, not the story driving the people.

As efforts towards fairer and truer representations of racial and ethnic identity in theatre have resulted in particular shows becoming flashpoints – with The Mikado in Seattle and New York, with The Mountaintop at Kent State, with Evita and In The Heights in Chicago, The Prince of Egypt in the Hamptons and so many more – one of the more frequent and derisive responses has been, “It’s called acting.” That is to say, ‘Oh, it’s all make believe,’ all little more than ‘let’s pretend,’ and as such shouldn’t be held to the same scrutiny or standard as say, the make-up of juries or the population of schools. It says that since the discipline is about taking on a persona, the reality of the person doing so shouldn’t be considered, shouldn’t matter. The phrase condescends to anyone who dares think otherwise.

Those who would reduce efforts toward equity in the arts might wish to isolate them as being the result of identity politics or political correctness. The “it’s called acting” claim is, make no mistake about it, an argument for the status quo, for tradition, for the denial of opportunity, for erasing race. It expresses the thinking that gives awards to people who pretend to be disabled on stage and screen, while making it difficult for people with disabilities to attend cultural events, let alone be a participant in creating them. It is the mentality that loves West Side Story, but cries foul when songs sung by characters who speak Spanish are translated into and performed in Spanish.

“It’s called acting” is the response of those who perceive their long-held dominance, their tradition, as threatened, their own position as being at risk. “It’s called acting” sustains systemic exclusion. After all, as the saying goes, “When you’re accustomed to privilege, equality looks like oppression.” Privilege abounds in the arts, on stage, backstage and in the seats.

If we lived in a society, a country, where everyone was indeed equal in opportunity, then the arguments for paying heed to the realities of race, ethnicity, gender and disability might be concerns that could be set aside. But that’s far from the case, and if the arts are to be anything more than a palliative, they must think not just of artifice, but also about the authenticity and context of what they offer to audiences.

For the arts to survive, they must move forward, lest they become antiquated. In a society where the balance of ethnicity and race is shifting, it is incumbent upon the arts to at last fully welcome and support all voices and allow them to portray and tell their stories as well as the stories of others, instead of being forced to assimilate into some arbitrarily evolved template. There should to be an acknowledgment of how the lived experience can contribute to the arts, rather than denying its presence or validity, along the lines of the canard, “I don’t see color.”

There is no absolute in the arts, no definitive good or bad, right or wrong. The act of creation and the response to that act exist simultaneously in the eye of the creator and beholder (the audience). Consequently, the arts give rise to phalanxes of arbiters at almost every level – teachers, directors and artistic directors, and critics – who seek to guide and even control training, practice and opinion, each in their own way. When those arbiters have disproportionate influence, or in fact become gatekeepers, they assume a greater responsibility, one that goes beyond themselves into the field as a whole. How they are empowered, what they believe, becomes essential to sustaining – or diminishing – the arts.

When it comes to respect and recognition, diversity and inclusion, there is a new arts narrative being written right now. Within that process there are progressives making change, late adopters who are coming to understand, and reactionaries who want to hold on to the past. If we believe that art has value, so do the ethics and process of making it. Being unaware, or worse still, dismissive of how the arts are changing and how the arts reflect society, would keep the field trapped at a moment in time, one already mired in the past, as the world advances. That’s the road to irrelevance, which the arts cannot afford.

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts.

December 23rd, 2015 § § permalink

Still from NYGASP video spot on YouTube

Oh, New York Gilbert and Sullivan Players, what are we going to do with you?

It was surprising to many that you thought you could do a “classic” yellowface Mikado in New York in 2015. But you also responded pretty quickly once there was an outcry against the practice, with the first blog posts of dismay (from Leah Nanako Winkler, Erin Quill, Ming Peiffer and me) posted on Tuesday and Wednesday and the production canceled by midnight on Friday morning. You’ve promised to bring your Mikado into alignment with current sensibilities at some point in the future, and I’m one of the many people who had cordial conversations with your executive director David Wannen in the wake of the September controversy.

So one can’t help be brought up short by your current commercial for The Pirates of Penzance, the production which replaced The Mikado at NYU’s Skirball Center. Shot in the Old Town Bar just north of Union Square, it features pub denizens having a Gilbert & Sullivan sing-off with some piratical looking men, as well as some geriatric British naval officers. All in good fun, it seems.

So why is there an admittedly brief shot in the ad of three yellowface geishas in a bar booth being leered at (by telescope, no less) by the British officers? Why is there still yellowface as part of advertising a production that was scheduled to eradicate yellowface?

Now I’m fully prepared to acknowledge this is probably an old TV spot, and all that has been changed is the superimposed show title, venue and number to call for tickets at the end. In fact, having watched New York television for much of my life, I’d say this spot could be quite old, and may well have emanated from days when Pirates, The Mikado and H.M.S. Pinafore were the bedrock of your repertory.

But in light of all that has happened over the past four months, seeing those faux-Asian women giggling behind their fans seems wholly out of place, if not a slap at those who advocated for a more enlightened take from you going forward. I acknowledge the effort and cost of recutting, or even reshooting, a commercial, but it might have been wise for you to not keep propagating the very imagery that led you to decide to cancel your production.

There’s no way to know whether you’re buying broadcast or cable time for the spot, but you just posted it to YouTube at the beginning of this month. This morning, the spot was featured in an e-mail blast you sent. So this possibly vestigial ad is still very much part of your marketing.

As I noted in a conference call with David Wannen, it is not lost on us that Albert Bergeret, the company’s artistic director, has not – so far as I know, and I’d be happy to be corrected – publicly expressed his support for the decision to remove The Mikado from your repertoire pending a reconception. Even this brief glimpse of yellowface suggests that the message of respecting ethnicities other than white hasn’t really sunk in. In fact, this could be seen by some as you winking at the controversy and telling your regular audiences that your “traditions” will be upheld, even if your sole intent was to economize and recycle an existing ad.

C’mon NYGASP, you said you were going to do better. You’ve taken some important steps, but it seems you’ve still got a ways to go.

Thanks to Barb Leung for sharing the e-mail and video from NYGASP.

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts.

December 23rd, 2015 § § permalink

New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players commercial

Oh, New York Gilbert and Sullivan Players, what are we going to do with you?

It was surprising to many that you thought you could do a “classic” yellowface Mikado in New York in 2015. But you also responded pretty quickly once there was an outcry against the practice, with the first blog posts of dismay (from Leah Nanako Winkler, Erin Quill, Ming Peiffer and me) posted on Tuesday and Wednesday and the production canceled by midnight on Friday morning. You’ve promised to bring your Mikado into alignment with current sensibilities at some point in the future, and I’m one of the many people who had cordial conversations with your executive director David Wannen in the wake of the September controversy.

So one can’t help be brought up short by your current commercial for The Pirates of Penzance, the production which replaced The Mikado at NYU’s Skirball Center. Shot in the Old Town Bar just north of Union Square, it features pub denizens having a Gilbert & Sullivan sing-off with some piratical looking men, as well as some geriatric British naval officers. All in good fun, it seems.

So why is there an admittedly brief shot in the ad of three yellowface geishas in a bar booth being leered at (by telescope, no less) by the British officers? Why is there still yellowface as part of advertising a production that was scheduled to eradicate yellowface?

Now I’m fully prepared to acknowledge this is probably an old TV spot, and all that has been changed is the superimposed show title, venue and number to call for tickets at the end. In fact, having watched New York television for much of my life, I’d say this spot could be quite old, and may well have emanated from days when Pirates, The Mikado and H.M.S. Pinafore were the bedrock of your repertory.

But in light of all that has happened over the past four months, seeing those faux-Asian women giggling behind their fans seems wholly out of place, if not a slap at those who advocated for a more enlightened take from you going forward. I acknowledge the effort and cost of recutting, or even reshooting, a commercial, but it might have been wise for you to not keep propagating the very imagery that led you to decide to cancel your production.

There’s no way to know whether you’re buying broadcast or cable time for the spot, but you just posted it to YouTube at the beginning of this month. This morning, the spot was featured in an e-mail blast you sent. So this possibly vestigial ad is still very much part of your marketing.

As I noted in a conference call with David Wannen, it is not lost on us that Albert Bergeret, the company’s artistic director, has not – so far as I know, and I’d be happy to be corrected – publicly expressed his support for the decision to remove The Mikado from your repertoire pending a reconception. Even this brief glimpse of yellowface suggests that the message of respecting ethnicities other than white hasn’t really sunk in. In fact, this could be seen by some as you winking at the controversy and telling your regular audiences that your “traditions” will be upheld, even if your sole intent was to economize and recycle an existing ad.

C’mon NYGASP, you said you were going to do better. You’ve taken some important steps, but it seems you’ve still got a ways to go.

Thanks to Barb Leung for sharing the e-mail and video from NYGASP.

December 22nd, 2015 § § permalink

Jonathan Larson’s Rent at PACT in Tullahoma TN (photo by Howard Sherman)

I honestly wish I could figure out what makes one blog post a roaring success, and another a blip on the radar. Certainly the topic under discussion has some impact, but readership seems just as likely to be affected by the title, a photo, the Facebook algorithm, the timing of a tweet, what else is happening in the world, and so on. In short, I have no idea.

In looking over my most-read posts of 2015, I do know which ones took a great deal of research and time, and which were dashed off in under an hour. I know which ones were written after a great deal of consideration, and which were wholly reactive to something I read or heard. They don’t necessarily correlate to readership at all.

I am surprised by the way in which my most-read posts were grouped in the latter half of the year, with seven coming since October 29. Is there any correlation with the fact that I began regularly working out of The New School Drama offices starting in early October, in my new role as director of the Arts Integrity Initiative? I think it’s just coincidence, but it’s possible that the new environment meshed with some significant incidents to yield my most successful writing.

While it may seem paradoxical to offer up my most-read work once again, I have no doubt that there are plenty of people who didn’t read one or more of these when they were first posted, and perhaps there are a few people who would like to catch up with them now. You’ll note I’m not providing them in order of popularity, because it’s not a contest, but I can say that even within these ten, there’s a differential of some 10,000 views.

* * *

July 3: Preparing For Anti-“Rent” Messages From Tennessee Pulpits

I had spoken with the leadership of the PACT community theatre in Tullahoma, Tennessee when they first began experiencing resistance to their production of Rent, but they decided that they’d prefer to try to address the opposition on a local basis. But ten days before performances were to begin, they learned of a letter in opposition to the show that was being circulated to the local clergy, and felt it was time for me to take up their cause and make it a national issue. I traveled to Tullahoma for the opening night, where I was welcomed by numerous members of the community, including the mayor, but the opposition had failed and the show played to an enthusiastic crowd. A prayer circle outside the theatre, in quiet protest of the production, drew only four people, including the two pastors who had been most opposed to the show.

August 1: Disrespecting Playwrights And Their Words with Young Players in

Minnesota

Words Players Theatre found itself in the midst of a firestorm when several bog posts, mine among them, questioned their practice of soliciting plays for production with their teen actors, but saying that the director had the final word over the show, contrary to the tenets of The Dramatists Guild. I stand by what I wrote at the time, but I was troubled by the degree of vehemence that some directed at the company, which didn’t necessarily seems the best way to educate students, their parents and the company’s leadership about respect for scripts in production. I ultimately wrote a second post, trying to walk back some of the rhetoric that surrounded this situation, not just mine, by the way.

September 15: Putting On Yellowface For The Holidays With Gilbert & Sullivan & NYU

I was far from the only person to speak out against the archaic, stereotypical use of yellowface in a production of the New York Gilbert and Sullivan Players production of The Mikado, but I was among the first, with my blog post going online alongside two others on Tuesday, September 15. The groundswell of reaction grew very quickly in subsequent days, and advocates against the practice of yellowface awoke three days later to find, with great surprise, that the production had been canceled. NYGASP says they will return with a reconceived Mikado that’s appropriate to 21st century America. Perhaps I’ll be writing about that in 2016.

October 29: When A White Actor Goes To “The Mountaintop”

It took three weeks after the production closed for word of Katori Hall’s Olivier Award-winning play being produced with a white actor as Martin Luther King to find its way to general awareness, but once it did, it brought great scrutiny to this production, at a community theatre based out of Kent State University’s Department of Pan-African Studies. What was even more remarkable, and remains still less known, is that the concept of having white and black actors each do four performances as Dr. King never happened – the white actor played the role for the entire run.

November 1: She Has A Name: Casually Diminishing Women In Theatre

I wasn’t exactly mystified as to why an interview with Pam MacKinnon carried a headline that mention her collaborators Al Pacino and David Mamet, both more famous, but it didn’t seem right that the person the paper actually spoke with was subordinated in this way. Intriguingly, not long after I posted my piece, the headline was altered, removing Mamet and Pacino – but it still didn’t mention MacKinnon by name. I was intrigued to discover that in coming up with a headline, I had birthed a Twitter hashtag: #SheHasAName.

November 2: A Seattle Theatre Critic Flies Past An Ethical Boundary

Critic offers his extra complimentary press ticket for sale, via the personals section. This one pretty much wrote itself. But I have to say that I quickly came to regret the tone of this piece, because I let myself succumb to snark precisely because it was so easy in this case. I should have stuck to the facts and let the story speak for itself. My feelings about what this critic did (or tried to do) haven’t changed, but I should have done better.

November 13: Erasing Race On Stage At Clarion University

Coming on the heels of the Mountaintop situation at Kent State, this dispute over racial representation in a college production of Jesus In India at Clarion University led to playwright Lloyd Suh pulling the rights to the show. There was a backlash against Suh from those who didn’t understand, or didn’t wish to understand, what it means to have white actors, even students, playing characters of color. Statements from university figures to the press only fed the uproar. But it has led to multiple offline conversations between Suh and the professor who was directing the show, and between the professor and me as well. Suh and I will be visiting the KCACTF Region 2 festival in a few weeks where we’ll meet for the first time and discuss the issue with the college students and their professors in attendance.

December 2: What Is Being Taught About The Director-Playwright Relationship?

After the heated dialogues that both The Mountaintop and Jesus in India engendered, on social media, in comments sections and in direct correspondence, I was moved to wonder aloud about how the playwright-director dynamic was being addressed in college training programs, both undergraduate and graduate. It prompted yet more comments and e-mails, and frankly helped me to learn a great deal more and provide the basis for further exploration. The post became the basis for a panel added to the KCACTF Region 3 festival, and I’ll be headed to Milwaukee to participate in the conversation right after the first of the year.

December 3: What Does “Hamilton” Tell Us About Race In Casting?

With Hamilton being cited as a reason why white actors should be permitted to play characters of color, I took the opportunity of a previously scheduled and wholly unrelated interview to ask the show’s writer-composer-star Lin-Manuel Miranda for his take on race on stage, both in his own work and the work of others. He was, as always, thoughtful and eloquent, during his dinner break on a two-show day.

December 9: Black Magic Crosses Directing & Design Line in Connecticut

When a community/semi-professional theatre in Connecticut staged a production that looked startlingly like a professional production that had been stage nearby three years earlier, it was an opportunity to address the issue of appropriation from other productions and what constitutes originality in directing and design. While the company in question suspended performances within 24 hours, and have subsequently restaged the show on a new set, the outpouring of anecdotes (and expressions of frustration) about productions that have slavishly copied others came pouring out. I expect to write more on this subject.

* * *

October 16: When A Facebook Comment Says More Than a Long Blog Post About Diversity

While it didn’t make the list of my ten most read posts, top on my list of posts that I wish had been more widely read is this one. Written on a day when a combination of medications for an infection laid me low and found me laying on my sofa most of the day, an array of tweets and comments roused me to string together a few sentences which were probably my only coherent thoughts until the drugs wore off. Even if you don’t read the whole post, take a look at the italicized midsection, which is what I actually wrote that day; the rest is subsequent framing.

June 9: If The Arts Were Reported Like Sports

Truth be told, this was one of my ten most read posts of 2015, but that has little to do with what I actually wrote and everything to do with the video I’d discovered and embedded, once again with framing material that isn’t essential to enjoying the video. My greatest contribution was a snappy title. But if you haven’t seen it and need a laugh at year end, this vid’s for you.

* * *

My thanks to everyone who read, commented, shared, tweeted or wrote to me in connection with my writing this year, and special thanks to those who brought situations to my attention so that I could explore them and share them even more broadly. You all have my very best wishes for a safe, happy, arts-filled 2016.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts and interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts.

October 30th, 2015 § § permalink

From the Fargo Moorhead Opera website

As I write, if you visit the website of the Fargo Moorhead Opera, you’ll find an evocative image of a beautiful young Asian woman used in conjunction with the company’s production of Madama Butterfly, playing this weekend in North Dakota. However, upon reading a feature story in yesterday’s Fargo Inforum about the production, you’ll learn that the lead actress in the show itself isn’t the woman who appears in the ads, and isn’t Asian at all, but rather a Caucasian of German extraction. So what’s the deal with the false advertising?

Mathew Edwardsen and Carla Thelen Hanson in Fargo Moorhead Opera’s Madama Butterfly (photo by Carrie Snyder)

I can think of any number of reasons why a marketing image might not match exactly what appears on stage – the cost of an original photo shoot vs. stock photography, the availability of performers sufficiently in advance of rehearsals to create the image for a months long campaign, and so on. But in the case of the Fargo Moorhead Opera, what they’ve done, whether intentionally or not, is a case of bait-and-switch, wherein they have sold what appears to be an authentically cast production of Madama Butterfly, but will be presenting one which traffics in yellowface. Why is an Asian face appropriate for their advertising, but not for their stage?

In the wake of controversies in Seattle and New York over yellowface productions of The Mikado, I don’t think I need to explain once again why the practice of casting Caucasian actors as Asian characters is offensive to the Asian community and an insult to anyone who seeks genuine diversity in performance. After all, people can and have read about the issue in recent weeks from Leah Nanako Winkler, Ming Peiffer, Rehana Lew Mirza, Nelson Eusebio and Desdemona Chiang, among others. I’ve had my say on the subject as well.

Any remotely reasonable rationalization about the chasm between FMO’s marketing and production of Butterfly goes out the window when the company’s general director David Hamilton talks about his views on the subject of casting roles with racial authenticity with Inforum.

“I don’t want to be limited who I can cast because I want the best performer for the role,” says David Hamilton, general director of the Fargo-Moorhead Opera. “We don’t have the luxury of unlimited choices to bring to Fargo.”

Hamilton says he hasn’t heard any rumblings about the FM Opera’s selection.

“Opera is about the voice and I want the best voice I can find to sing their role,” Hamilton says.

The “best performer for the role” argument is often deployed when casting in theater or opera has obviously failed to employ racial authenticity. It particularly fails for Hamilton and the FMO when one learns that the last time the company did Madama Butterfly, an Asian-American performer played the role. So the company has already shown that it can cast the role authentically.

That Hamilton “hasn’t heard any rumblings” about the casting, which I take care to note is a paraphrase and not a direct quote, may be because opera companies so frequently fail to cast for racial authenticity. It’s only this year that the Metropolitan Opera abandoned using blackface for their production of Otello – yet retained a Caucasian actor in the role. That Hamilton is unaware of any unhappiness over his casting could be a result of the circles in which he travels, and therefore hardly representative of anything more than his acquaintances, or perhaps it’s because Fargo has only a 3% Asian population. But whatever the reason, lack of protest doesn’t mean racial insensitivity is therefore condoned. Even in a community with a 90% white population, accurate representations of race matter.

As for the “opera is about the voice” argument, I must confess that this has always befuddled me. If opera were only concerts in tuxedos, or recordings, I might be prepared to grant the form more leeway. But once you have people in costumes and on sets, there is more to the performance than simply sound; what the audience sees is part of the experience. While there are many aspects of Madama Butterfly – and its descendent, Miss Saigon – that are deeply troubling to Asian-Americans, as both works trade in and perpetuate Asian stereotypes, if the work is to be done, at least let it be done with the most respect possible. That means Asian performers playing Asian characters. If there truly aren’t enough qualified Asian performers to meet the FMO standards, then that is a direct result of companies failing to cast artists of color often enough, and perhaps also a failing on the part of training programs – though if artists of color can’t get roles, that might be deterring them from pursuing operatic careers, in a vicious cycle.

“We know it’s not real, but we don’t care,” Hamilton told Inforum. “You have to suspend disbelief. … Under all that geisha makeup, who would know?” Well, I know, Mr. Hamilton, and Inforum readers know, since the reporter who wrote the story, John Lamb, made the effort to present an opposing viewpoint from Chelsea Pace, an assistant professor of movement in the department of theater arts at North Dakota State University. I think many other people are going to find out.

While it’s late in the game to have any effect on this weekend’s production, I hope David Hamilton and the board of directors of the Fargo Moorhead Opera are going to start hearing “rumblings” that they can’t and shouldn’t ignore, as a message to the FMO and other opera companies about demonstrating genuine respect and appreciation not only for vintage Eurocentric music traditions, but for all people who make up this country, as well as the performing community and its audiences – and potential audiences. That goes for the Metropolitan Opera as well, which is doing Madama Butterfly this season with two performers sharing the title role, only one of whom is Asian. Even half measures are not enough.

If you’d like to share your thoughts on this topic with Fargo-Moorhead Opera general director David Hamilton, you can write to him at director@fmopera.org.

Howard Sherman is the interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts.

September 15th, 2015 § § permalink

Please consider the following two statements.

- In a description of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado: “The location is a fictitious Japanese town.”

- “There are no ethnically specific roles in Gilbert and Sullivan.”

The conflict between these two statements seems fairly obvious since even in a fictitious Japanese village, the residents are presumably Japanese, and that is indeed ethnically specific, even if they are endowed with nonsensical names that may have once sounded vaguely foreign to the British upper crust.

The NYGASP Production of The Mikado

Now one could try to explain away this dissonance by saying that the statements are drawn from conflicting sources, however they are both taken from the website of the New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players. The company, which has been producing the works of G&S in Manhattan for 40 years, will be mounting their production of The Mikado at NYU’s Skirball Center from December 26 of this year through January 2, 2016, six performances in total.

It is hardly news that The Mikado is a source of offense and insult to the Asian-American community, both for its at best naïve and at worst ignorant cultural appropriation of 19th century Japanese signifiers, as well as for the seeming intransigence of 20th and 21st century producers when it comes to attempting to contextualize or mitigate how the material is seen today. Particularly awful is the ongoing practice of utilizing yellowface (Caucasian actors made up to appear “Asian”) in order to produce the show, instead of engaging with Asian actors to both reinterpret and perform the piece. Photos of past productions by the NY Gilbert & Sullivan Players suggest their practice is the former.

“History!,” some cry, “Accuracy to the period!” That’s the same foolish argument recently spouted by director Trevor Nunn to explain why his new production of Shakespeare history plays featured an entirely white cast of 22. “But The Mikado is really not about Japan! It’s a spoof of British society,” is another defense. But it has been some 30 years since director Jonathan Miller stripped The Mikado of its faux Japanese veneer and made it quite obviously about the English, banishing the “orientalist” trappings from 100 years earlier. Besides, reviews of prior NY Gilbert & Sullivan Players productions note that the script is regularly updated with topical references germane to the present day, so claims to historical accuracy have already been tossed away.

Looking at the New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players (NYGASP) cast on their website, it appears that the company is almost exclusively white. While our increasingly multicultural society makes it difficult and reductive to assume race and ethnicity based on names and photos, I noted a single person who I would presume to be Latino among the 70 photos and bios, and seemingly no actors of Asian heritage. While I should allow for the possibility that there may be new company members to come, it seems clear that the preponderance of The Mikado company will be white.

Was it only a year ago that editorial pages and arts pages erupted over a production of The Mikado in Seattle precisely because of an all-white cast? Is it possible that in the insular world of Gilbert and Sullivan aficionados, word didn’t reach the founder and artistic director of NYGASP, Albert Bergeret? I doubt it. In Seattle, the uproar was sufficient to warrant a gathering of the arts community to air grievances and discuss the lack of racial and ethnic awareness shown by the Seattle troupe. That it followed on another West Coast controversy, a La Jolla Playhouse production of The Nightingale, a musical adaptation of a China-set Hans Christian Andersen tale that utilized “rainbow casting,” rather than ethnically specific casting, only added fuel to the justifiable controversy.

This year, The Wooster Group sparked protest on both coasts with its production of Cry Trojans, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida that had members of an all-white company in redface portraying Native Americans and appropriating Native American culture, as viewed through the wildly inaccurate prism of American western movies. Yet in a victory for ethnically accurate casting earlier this year, a major Texas theatre company recast its leading actor in The King and I when it was made abundantly clear by the Asian American theatre community that a white actor as the King of Siam simply wasn’t acceptable.

The NYGASP production of The Mikado (photo by William Reynolds)

That NYGASP will be performing on the NYU campus makes the impending production all the more surprising. It is highly doubtful that the university’s arts programs would undertake an all-white Mikado any more than they would do an all-white production of Porgy and Bess (although copyright probably prevents them from attempting the latter). College campuses are where racial consideration is at the forefront of thinking and action. Is it possible that The Mikado is in the Christmas to New Year’s slot precisely because school will not be in session and the university will be largely vacant, mitigating the potential for protest? Without school in session, NYGASP can’t even take advantage of the university community, if both parties agreed, to contextualize this production as part of a broader cultural conversation, not to explain it away, but to interrogate the many issues it raises.

“We can’t find qualified performers in the Asian-American community,” is another one of the frequent defenses of yellowface Mikados. After 25 years of countless productions of Miss Saigon, a revised Flower Drum Song with an entirely Asian-American cast, and two current Broadway productions (The King and I and the impending Allegiance) with largely Asian casts, it’s not possible to claim that the talent isn’t out there. Excuses about training or worse, diction (which is noted on the NYGASP site), are utterly implausible.

Admittedly, even with racially authentic casting, The Mikado is a problematic work, since it is rooted in ignorant stereotypes of Japan and not in any real truth. Does that make it unproducible, like, say The Octoroon (as explored by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s revisionist An Octoroon), or any number of early musical comedies which traded in now-offensive racial humor? No, as Jonathan Miller proved 30 years ago. And while it seems contradictory, even if the text and characterizations of The Mikado are retrograde, if it is to be done, at least it should be interpreted by Asian actors, who are afforded too little opportunity in theatre, musical theatre, operetta and opera as it is. There are any number of Asian performers who will discuss their reservations about Miss Saigon as well, but at least it affords them work, and the chance to bring some sense of nuance and authenticity to the piece. The same should be true of The Mikado.

The upset surrounding The Mikado at the Skirball Center has just begun to bubble up, originating so far as I saw with Facebook posts from Leah Nanako Winkler, Ming Peiffer, and Mike Lew; Winkler has already posted a blog in which she speaks candidly with NYGASP’s Bergeret and Erin Quill has a strong take as well. Hopefully a great deal more will be said, with the goal that instead of keeping The Mikado trapped in amber as G&S loyalists seem to prefer, it will be brought properly into the 21st century if it is to be performed at all. In a city as large as New York, maybe there are those who see six performances of The Mikado as being insignificant and not worthy of attention. But in a city as modern and multicultural as New York, can and should a yellowface, Causcasian Mikado be countenanced? Now is the time for the last (ny)gasp of clueless Mikados.

Update, September 16, 2 pm: NYGASP has replaced the home page of their website with a statement titled, “The Mikado in the 21st Century.” It reads in part:

Gilbert studied Japanese culture and even brought in Japanese acquaintances to advise the theater company on costumes, props and movements. In its formative years, NYGASP similarly engaged a Japanese advisor, the late Kayko Nakamura, to ensure that our costumes and sets remain true to the spirit of the culture that inspired them. We are dedicating this year’s production of The Mikado to her memory.

One hundred and forty years after the libretto was written, some of Gilbert’s Victorian words and attitudes are certainly outdated, but there is vastly more evidence that Gilbert intended the work to be respectful of the Japanese rather than belittling in any way. Although this is inevitably a subjective appraisal, we feel that NYGASP’s production of The Mikado is a tribute to both the genius of Gilbert and Sullivan and the universal humanity of the characters portrayed in Gilbert’s libretto.

In all of our productions, NYGASP strives to give the actors authentic costumes and evocative sets that capture the essence of a foreign or imaginary culture without caricaturing it in any demeaning or stereotypical way. Lyrics are occasional altered to update topical references and meet contemporary sensibilities; makeup and costumes are intended to be consistent with modern expectations.

Update, September 16, 4 pm: Since I made the original post yesterday, several other pertinent blog posts have appeared, and I wanted to share them as well. There are many aspects to this conversation.

From Ming Peiffer, “#SayNoToMikado: Here’s A Pretty Mess.”

From Melissa Hillman, “I Get To Be Racist Because Art: The Mikado.”

From Chris Peterson, “The Mikado Performed In Yellowface and Why It’s Not OK.”

From Barb Leung, “Breaking Down The Issues with ‘The Mikado’”

Update, September 17, 7 am: NYGASP has posted the following message on their Facebook page:

Update, September 18, 8 am: Overnight, NYGASP announced that they are canceling their production of The Mikado at the Skirball Center, replacing it with The Pirates of Penzance. A statement on their website reads as follows:

New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players announces that the production of The Mikado, planned for December 26, 2015-January 2, 2016, is cancelled. We are pleased to announce that The Pirates of Penzance will run in it’s place for 6 performances over the same dates.

NYGASP never intended to give offense and the company regrets the missed opportunity to responsively adapt this December. Our patrons can be sure we will contact them as soon as we are able, and answer any questions they may have.

We will now look to the future, focusing on how we can affect a production that is imaginative, smart, loyal to Gilbert and Sullivan’s beautiful words, music, and story, and that eliminates elements of performance practice that are offensive.

Thanks to all for the constructive criticism. We sincerely hope that the living legacy of Gilbert & Sullivan remains a source of joy for many generations to come.

David Wannen Executive Director New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players

Update, September 18, 3 pm: The NYGASP production of The Mikado was scheduled to be given a single performance on the campus of Washington and Lee University this coming Monday evening, September 21. As of this afternoon, the production has been replaced with the NYGASP production of The Pirates of Penzance.

* * *

Howard Sherman is the interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts.

October 16th, 2014 § § permalink

As headlines go, “A challenge for the arts: Stop sanitizing and show the great works as they were created” embodies what many of us were taught in school about the well-made essay: tell people what you’re going to tell them, offer support for your thesis, then tell them what you’ve told them. Unlike many instances where newspaper headlines misrepresent the content of the article that follows, I would say that Philip Kennicott’s article in The Washington Post on October 4th was accurately summarized. As a result, the unsettled feeling I had upon reading it remained with me as I read the piece itself, and long afterwards.

To select two paragraphs which explicitly reinforce Kennicott’s thesis, I offer first:

Censoring art to make it more palatable to contemporary audiences warps our sense of goodness, making our tolerance seem magically delivered rather than hard-won through centuries of struggle. It erases the complex, chaotic history of tolerance, especially problematic at a moment in history when the West is given to lecturing the “rest” on new and culturally alien extensions of compassion and decency across gender, sexual and sectarian lines.

Later in the piece, Kennicott asserts:

To preserve their independence, the arts need to stand resolutely aside from the increasingly complex rituals of giving and taking offense in American society. The demanding and delivering of apologies, the strange habit of being offended on behalf of other people even when you’re not personally offended, the futile but aggressive attempt to quantify offensiveness and demand parity in mudslinging — this is the stuff of degraded political discourse, fit only for politicians, partisans and people who enjoy this kind of sport.

I’m troubled by Kennicott’s charge that the arts in some way fail when they demonstrate sensitivity to prevailing social attitudes. While there are certainly many great works of art that contain misogynistic, racist, and classist attitudes (to name but three), to present them today and excuse them from criticism simply because they are “great” fails to in any way address how society has advanced when addressing inclusion, diversity and equality in the arts. It’s no small matter that the majority of the great works of the Western arts canon were also written by white men, and while that doesn’t negate their value, presenting them as if preserved in amber can be not only profoundly offensive but artistically stultifying.

I don’t happen to take to reworkings of classic works simply in order to fend off complaint; erasing the n-word from Huckleberry Finn struck me as patently absurd when a new edition doing just that appeared a few years ago. By way of example, the same holds true for productions of To Kill A Mockingbird which would eradicate that same word. In both cases, it’s a disservice both to the work and those who consume it. Frankly, I also don’t believe that any work should be, in total, deemed off limits because of changing mores.

But this conversation isn’t as binary as Kennicott presented, a choice between fidelity or censorship. Whether considering a work taught in classrooms or presented professionally on stage, one also has to factor in the interpretation and context, both separately and together.

Mark Lamos’s production of The Taming of the Shrew at Yale Rep in 2003 (T. Charles Erickson photo)

There are many Jews who think The Merchant of Venice should never be performed, due to its ant-Semitic elements; I don’t happen to share their opinion. I would however be troubled to find a production that takes to heart the classification of the play as one of Shakespeare’s comedies, playing the shaming of Shylock for boisterous laughs. I know many people who feel the same way about The Taming of the Shrew, but a production by Mark Lamos at Yale Rep some years ago, featuring an all-male Latino cast, took the casual misogyny of the play, once seen as comic, and transmuted it into an exploration of modern male sexual identity, holding the play at a distance to be examined through a modern framing device, rather than asking us to accept the humbling of Kate as a just dénouement. Given the volume of Shakespeare productions every year, I imagine there are numerous interpretations which don’t bowdlerize the language, but instead imbue the plays with new insight; the Donmar Warehouse’s all-female Julius Caesar and Henry IV surely are important examples.

Mhlekazi Andy Mosiea as Tamino in Isango Ensemble’s The Magic Flute (Keith Pattison photo)

As I contemplated this issue, I happened upon online information about a South African production of The Magic Flute by the Isango Ensemble, currently touring the U.S., which has an all-black cast; this presumably immediately alters the perception of the blackamoor Monostatos, who Kennicott used as a key discussion point. At the same time, I was reading a great deal about the Metropolitan Opera’s imminent production of The Death of Klinghoffer, which is at the center of enormous controversy over its depiction of an incident from the real historical past, but on which I can offer no opinion because I haven’t seen it; the controversy only points up the fact that it isn’t solely works from the distant past which can provoke.

Citing counter-examples production by production would be endless, so let me turn to the issue of context. When a class is taught or a company produces a work whose social attitudes reflect less enlightened views, it’s worth noting whether any framing is provided, for students or audience. If a teacher assigned Huckleberry Finn without prior discussion and comprehensive followup, I would question their tact and their skills; to foist the book on students sans preface would, I imagine, be very upsetting to students. The same holds true for reading or seeing The Merchant of Venice without addressing the status of Jews in Shakespeare’s era, in discussion or supporting materials. Exploring how or why we might see these works today, why they may hold value even when they contain retrograde views, seems essential. It won’t necessarily preempt controversy, but it certainly demonstrates that the people presenting the work understand its complexity and challenges, and that they hope to grapple with those challenges by presenting it in a new light.

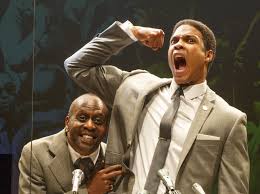

K. Todd Freeman and Ray Fisher in Fetch Clay, Make Man at New York Theatre Workshop

There are also examples of artists addressing work which would now be seen as offensive by placing it within the context of new works and adaptations. Screenings of films featuring Lincoln Perry, better known by the derogatory name Stepin Fetchit, who at one time was the most famous black actor in the movies, would likely be met by scorn if simply programmed without introduction or discussion of the actor and his character at the time he was working. However, playwright Will Power has worked to address Perry’s legacy by making him a leading character in the play Fetch Clay, Make Man, which places him alongside Cassius Clay (as he became Muhammed Ali) as two icons of African-American popular culture. It’s also unlikely that few theatre companies would produces the once hugely popular melodrama The Octoroon, with its far outdated racial views, but Branden Jacobs-Jenkins has deconstructed the work as part of his play An Octoroon, folding the original material directly into commentary on the same piece.

Jonathan Miller’s production of The Mikado for the English National Opera

There are many who defend The Mikado by citing Gilbert and Sullivan’s love of Asian culture and their efforts to represent it, but that often accompanies productions with white actors in yellowface; this ongoing controversy arose once again this summer in Seattle. But 28 years ago director Jonathan Miller found a way to present the work by resetting it in a seaside English resort, allowing the characters in what was widely known to be a spoof of the British aristocracy to be seen as exactly that, instead of antiquated racial caricatures. Again, context and interpretation is all.

I take exception to Kennicott’s characterization of “Cultural leaders who fret about art causing discomfort,” since it evidences a lack of comprehension of the role of those leaders. Yes, we should want all artistic ventures to be brave and bold, and to even take audiences places where they might not necessarily think to go. But they must do so in the context of serving their community, and indeed their many communities, because they do not and cannot exist in a vacuum where art cannot be challenged, often vigorously, in critiques and discussion simply because it has been declared art.

In every generation, art is a dialogue between artists and audiences, whether in performance or fixed texts and images; just as some works aren’t recognized or accepted when first created, there are also those which cease to hold meaning or whose meaning changes as society advances. If an artistic leader chooses to produce a season of vintage works with passé portrayals of women, people of color, people with disabilities, sexual orientation and so on as they might have first been seen, that is absolutely their right. But it is also the right of those who know the work or see it to challenge those decisions – though I abhor the kinds of threats that have emerged over Klinghoffer or Exhibit B at the Barbican, even as I support the rights of the voices which oppose those works to express their opinions. It is very easy in theory to say all works should remain fixed, but reality is another matter altogether.

There are no absolutes in this discussion. If works out of copyright are altered for this production or that, the work itself remains fixed for yet another day, and each example can be judged in relation to the original text. Inevitably, for every leader, whether teacher or producer, it is a matter of balancing a wide range of opinions and perceptions. I personally believe in art for art’s sake alongside art for audiences’ sake, but art for history’s sake serves only the past and runs the risk of propagating the failings of the past. In the arts, history should not be wholly erased, but it should first and foremost be the foundation upon which we build a better future.

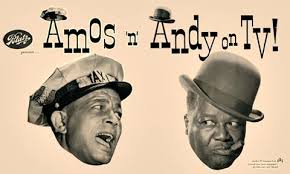

P.S. Among the examples Kennicott cites as falling prey to cultural sanitization is Amos and Andy. While it is true that the show was recognized as an avatar of racial insensitivity when viewed through the enlightened prism of the 1960s civil rights struggle, its absence from the airwaves or cable box is now due just as much to it no longer being commercially viable as to its racial stereotyping. That holds true as well for countless shows from the era, for reasons ranging from a changed society where the work is no longer seen as positive (such as my childhood favorites F Troop and I Dream of Jeannie) to their being in black and white and in the old TV aspect ratio. But Amos and Andy hasn’t been erased: you can view the TV episodes in the collection of the Paley Center for Media or buy the DVDs on Amazon and see for yourself why it’s now for the history books and academic, not mass entertainment.

P.S. Among the examples Kennicott cites as falling prey to cultural sanitization is Amos and Andy. While it is true that the show was recognized as an avatar of racial insensitivity when viewed through the enlightened prism of the 1960s civil rights struggle, its absence from the airwaves or cable box is now due just as much to it no longer being commercially viable as to its racial stereotyping. That holds true as well for countless shows from the era, for reasons ranging from a changed society where the work is no longer seen as positive (such as my childhood favorites F Troop and I Dream of Jeannie) to their being in black and white and in the old TV aspect ratio. But Amos and Andy hasn’t been erased: you can view the TV episodes in the collection of the Paley Center for Media or buy the DVDs on Amazon and see for yourself why it’s now for the history books and academic, not mass entertainment.

When I awoke Monday morning to a Facebook wall post from Daniel Goldstein, who was directing the show, saying that I “may or may not be name-checked” in Diva: Live From Hell, I understood why Morgan was being so insistent. After all, Daniel couldn’t be posting versions of that message on the pages of all of his Facebook friends as a marketing ruse to sell tickets to the show, could he?

When I awoke Monday morning to a Facebook wall post from Daniel Goldstein, who was directing the show, saying that I “may or may not be name-checked” in Diva: Live From Hell, I understood why Morgan was being so insistent. After all, Daniel couldn’t be posting versions of that message on the pages of all of his Facebook friends as a marketing ruse to sell tickets to the show, could he?