January 29th, 2019 § § permalink

If one looks around the website of The Neil Simon Festival, a yearly theatre event held in Cedar City, Utah, there’s a list of donors to the company. On that list are seven entries at the $100+ level. But the list is perhaps some 30 short, because that’s the approximate number of unlisted individuals who sent $150 to the Festival last year.

While the $150 sent by those people isn’t described by the Festival as a donation, it effectively is one for all but a single person. The $150 figure is derived from the submission fee playwrights are asked to provide as their entry fee to the Festival’s New Play Contest, now in its ninth year. While the Festival notes that every submission receives a written evaluation as part of the company’s response, it is not a fee for service. Playwrights are not offered the opportunity to submit and not receive an evaluation.

Richard Bugg, founder and executive producer of the Festival, said in a call with Arts Integrity that the $150 submission fee was new as of last year, markedly increased from their prior figure. He said it has had the effect of decreasing the submissions, from nearly 100 scripts to somewhere in the 30s. The deadline for the 2019 contest is 11:59 pm on February 1, so there is not yet a final count for this year.

Asked about the fee, which is notably high compared to other play competitions and workshop programs, Bugg explained that the fee is waived for any college or university that chooses and submits a single selection, though he said that none had done so. The Festival’s website states:

The entry fee is used in three areas: a) to help defray the cost of travel and lodging for the playwright, b) payment to our contest readers for their professional expertise, and c) contest administration (photocopying, advertising, etc. but not salary).

Bugg specifically said that the fee helps to underwrite payment to Douglas Hill, who reviews most of the scripts and writes the critiques. Bugg said that Hill is, “magnificent in looking at the structure of scripts and making suggestions.” The payment also helps to pay other reviewers engaged by Hill as needed. Bugg said he also reads all of the finalists’ scripts.

Hill also spoke to the effect of the submission fee, in an e-mail response to questions from Arts Integrity. “We have received as many as 120 submissions in some years, and as few as 20 in other years,” he wrote. “Unfortunately since the contest is less than 10 years old, and with the recent changes to the contest, it’s a little difficult to provide you with a good approximate number.

“We use it to some degree to weed out,” said Bugg. “We get a higher degree of script that way.” However, Bugg allowed that perhaps some worthy scripts might not be submitted due to the expense.

The season at The Neil Simon Festival, an independent not-for-profit organization, is short, only three weeks this coming year, with two shows a day five days a week, and with most actors performing in multiple roles akin to classic repertory format. The winner of the new play contest first receives a six-day staged reading in the year in which it is selected, and is then produced, for three performances, during the subsequent season. In 2019, that play will be I Left My Dignity in My Other Purse by Shelley Chester.

Asked whether the Festival was familiar with Dramatists Guild guidelines regarding play festivals and contests, Bugg said that he was not. Ralph Sevush, Executive Director for Business Affairs of the Guild, when informed of the $150 submission fee, provided the following guidance from the Guild’s best practices guidance:

BEST PRACTICE: The organization does not require a submission fee. Furthermore, the organization imposes no other obligation on the author or encumbrance on the work (e.g., ticket sales, participation fees, technical rentals, hiring fees, marketing, or other selling obligations), except for do-it-yourself (“DIY”) productions. The Guild has long disapproved of excessive submission fees, which not only undermine the benefit of any “award” or “royalty,” but also impose financial hardship on the author. Any other authorial obligations should be clearly noted up front; this is particularly true for DIY and similar festivals that require authors to self-produce their works.

Regarding payments to the authors when their winning works are performed, Bugg said that there were none. The playwright receives transportation and housing during both visits. Bugg explained, “There’s no royalties. Just being in the season is reward in our eyes.” Bugg did make clear that other playwrights in the Festival, including the Simon estate, are paid royalties.

The Neil Simon Festival, now in its 17th year, is admittedly a small company, operating on a budget of roughly $300,000 per Bugg. While Hill wrote, “We’re probably best defined as a professional non-Equity company,” that assertion is undermined by a casting notice from the Festival. The notice stipulates availability from June 3 to July 29 in Cedar City and 4-5 weeks of subsequent performance in Park City and Ivins, also in Utah. Regarding compensation, the website says only that, “Housing is provided along with a modest stipend.” Bugg noted that while he and several of the other leaders of the company are members of Actors Equity and do perform in the Festival, “We don’t do contracts for ourselves.”

That the Neil Simon Festival operates a new play contest in which playwrights are asked to pay a fee far above the typical competition, that the selected playwright receives no royalty for their work being presented to a paying public, and that actors are essentially volunteering for an entire summer’s engagement stand as three red flags about the company. These simply are not prevailing industry standards. Professionals are paid for their work.

That the company leadership – Bugg, Hill, and artistic director Peter Sham – all teach at the university level (Bugg and Sham at Southern Utah University and Hill at University of Nevada Las Vegas) also raises questions about the professional standards they are imparting to their students, separate from their Neil Simon duties. The encouragement to “work” for little or no pay runs contrary to the practices and expectations that should be instilled in aspiring artists. The suggestion that playwrights of new plays should be rewarded simply by virtue of being produced undermines the perceived value of authors’ creations. Actors shouldn’t be grateful for a place to sleep, petty cash, and stage time. High submission fees emphasize economic disparity among artists, making it possible only for those of means to enter competitions that require a significant outlay (very possibly diminishing the range and caliber of submissions and the program in the process).

When the clock strikes midnight on February 2, the Neil Simon Festival’s Play Contest entry period will close. But hopefully with some serious thinking resulting from outside scrutiny, the leadership of the company will rethink the economic model under which they function and the messages they communicate through their operating model. Perhaps they can use it to leverage more funding, locally or nationally. Because however great the experience may be for those involved, exorbitant fees for contest entrants and free labor by actors don’t add up a professional experience. It ends up costing the artists to be involved, even as audiences pay in order to see that work. And that’s no laughing matter.

August 18th, 2016 § § permalink

Now in its 20th year, the New York International Fringe Festival, better known as FringeNYC, has presented nearly 4,000 productions for five-performance runs each summer, sustaining a beehive of theatrical activity in spaces on the Lower East Side. In contrast to many fringe festivals, all of which seem to owe a debt to the progenitor, the Edinburgh Fringe, FringeNYC is a curated festival, with its 200 annual productions chosen from an array of applications. Unlike reports from Edinburgh, which have some 8,000 productions scrambling for space and audiences each summer, FringeNYC engages all of the necessary spaces and doles them out to the productions they accept, controlling the probability of the highly speculative rents that have crept into Edinburgh. FringeNYC also negotiates an agreement with Actors Equity, provides lighting and sound equipment, and covers general liability insurance.

FringeNYC’s two decade history and success made last week’s “Biz Blip” from the Dramatists Guild to its members, challenging terms regarding subsidiary rights, or ongoing revenue, within FringeNYC’s authors agreements all the more surprising. While it was not sent as a press release or public statement, the missive, issued the night before the 2016 Festival began, quickly became a topic of conversation on social media. One of the early sources for non-Guild members was Isaac Butler’s Parabasis blog, which reproduced the item in its entirety. Headed “NYC Fringe Contract: Warning,” it read, in part:

Playwrights should be aware that the standard for fringe festivals around the world (including the US Association of Fringe Festivals, the Canadian Association of Fringe Festivals, and the Edinburgh Festival, the model on which most other festivals are based) is that, as presenting entities that are not actually producing the work, festivals are not entitled to subsidiary rights from authors. The NYC Fringe, however, under Article IV-B of their contract, requires an author to pay 2% of subsidiary rights revenues earned within 7 years of the festival (after the author’s first $20,000). And the contract does not limit the scope of its definition of “subsidiary rights,” so it includes every use of the play on a worldwide basis; this is a definition broader than a LORT theater or even a commercial off-Broadway producer might be granted.

Because Arts Integrity and its director Howard Sherman have ongoing relationships with both the Dramatists Guild (having worked with them on multiple instances of theatrical censorship and having received an award from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund) and FringeNYC and its producing artistic director Elena K. Holy (including reporting a 3-day “Fringe Binge” for Narratively.com and participating in a panel on censorship during the 2015 festival), it was incumbent that both parties have an opportunity to explain their policies and views.

* * *

In conversation at one of the FringeNYC Lounges on the first full day of the 2016 Festival, Holy said of the Guild statement, “My initial response is that most of what they’ve said is true about our contract. However our contract incorporates a Participants Manual, which is like 64 pages, and none of that was included [in the Guild’s summary of issues]. We don’t have an attorney on staff so we wrote the participants’ agreement in 1997 and haven’t really changed it much since then. Every year, facts, figures, dates and stuff change, and technology changes, so that part gets put into the Participants Manual.”

Regarding the Dramatists Guild’s explicit comparison to the Edinburgh Festival, Holy explained, “We call ourselves presenters, but my biggest point of contention with what the Dramatists Guild said is we should be compared to Edinburgh. They see Edinburgh Festival Fringe as an industry standard, which totally makes sense, they’re the granddaddy of them all, they were 50 years old when we started, but the model is very different. They charge a similar participation fee to us and then they hand you a list of venues, and say ‘Great, go out and rent one of these venues to produce your show in.’

“Our thought was that if we did that in New York City and set loose 200 shows all looking to book the same 16 days, forget ten grand a week it would be thirty to forty grand a week, just through supply and demand. So we rent the venues, equip the venues, we staff the venues, we do marketing, we do marketing speed dates, director speed dates, town meeting – we are very hands on, and we’re invested in their production and we like to have skin in the game. I like that we are an adjudicated festival.”

Regarding the festival’s economics, Holy said, “On our 2014 990 form, we operated on 86% earned income. We’re invested in our artists. We spend between $6,000 to $7,000 on each show at FringeNYC. Part of that is we want a) for them to be invested in us and b) if they see huge success, huge unlikely success, for having done the show at FringeNYC, which does about 13,000 industry and press comps a year, then we would like for that to be recognized in order to keep our participation fees low for future artists. In our 19, almost 20, years now of doing our festival, three shows have contributed to that.” She cites Urinetown, which paid approximately $5,000 in royalties to the festival, as well as Eva Dean Dance and Dixie’s Tupperware Party.

Holy acknowledges that some applicants resist FringeNYC’s terms.

“Our 2% clause,” she notes, “when a famous person walks into our office and fills out an application form and doesn’t submit their script, or when someone’s agent calls us and says, ‘I know they’ve been accepted into the festival but we can’t sign this,’ it’s a pretty good indication that they don’t need one of our 200 slots.

“We only have 200 spots and if their career is beyond what we can offer, if their play is being produced that widely or if in the past they’ve had opportunities on Broadway, there’s really no reason for our 2500 volunteers to volunteer to help make somebody’s show happen when that somebody has ample opportunity elsewhere. So I’m not ashamed to say it scares a lot of people off and they’re probably people that shouldn’t be applying for our festival even.”

But isn’t it possible that FringeNYC is capitalizing on people’s desire to get their work seen on a New York stage, whatever the cost?

“Are they,” Holy asks, “given that it’s kicked in three times in 20 years? Given that it doesn’t kick in until after they’ve made $20,000, which actually these days means that you have to have a major motion picture made out of your play? Are they really encumbering their project? Most often what happens here is it’s not even the plays from FringeNYC that gets picked up. It’s our playwrights’ second and third plays that are what’s being produced regionally, or that’s when they get the Netflix series or the television show or whatever. So we certainly are not still around because of that $5,000 from Urinetown in 2000, or it was probably 2001 that it started.” She notes that the Fringe has received no subsidiary income from such shows as Matt and Ben and Silence! The Musical.

* * *

Regarding the citation of other fringe festivals in the Dramatists Guild’s “Biz Blip,” David Faux, associate executive for business administration at the Guild, explained in a phone conversation, “When we speak to festivals and producers, every single one of them can say, ‘We’re special, we’re different, we do things differently from what the other people do,’ and invariably they’re telling the truth. That’s the beauty of the theatre, every festival has its unique attributes, every producer has his or her unique attributes that they bring that nobody else can bring. That’s part of the chemistry of good theatre. So the fact that they do something that other festivals don’t do, we can just look at the other festivals and say, ‘Yeah, but they do things that you don’t.’ Why would the thing that they do different have to rest on the authors’ shoulders? Why should the author be burdened with a unique attribute of the festival?”

“We look at thousands of contracts that our authors ask us to review every year,” said Faux. “When you see that many contracts you see patterns and you see where theatres and festivals are deviating.”

“It’s always germane what other people are doing in the market,” notes Faux. “With the Guild in particular we don’t tell members whether or not to sign contracts, we don’t dictate terms of contracts, but we do express our opinions when we believe a contract has substandard terms. In that way, all we have is the comparison.”

Asked to explain a very general idea of common practice regarding subsidiary rights, Faux said, “Commercial theatres certainly receive subsidiary rights. They’re taking on a lot of risk and this is how the author shares in that risk on the back end. If it works out, the success of the authors work can go back to the commercial producer or the investors.

“With not-for-profits, there’s a different structure, because they are receiving grant monies, they don’t pay taxes, they get a certain number of benefits that commercial producers don’t. So that’s why it would be unusual to see an author giving subsidiary rights of more than 5% to a not-for-profit theatre. That’s about the top when you talk about regionals, LORTs. We’ve seen a trend lately of only having subsidiary rights kick in after a significant windfall, and by significant we’re talking $40,000 to $50,000. These are general terms.

“At festivals though, you don’t see authors having to yield a revenue stream on their future revenue. That’s what’s different about this. You know what happens, a theatre festival in Wichita, Kansas will hear that NYC Fringe is getting subsidiary rights from the author. And that festival in Wichita doesn’t say, ‘Oh, it’s New York City, of course it gets something we don’t.’ That festival in Wichita says, ‘Our production values are even better than what they’re getting in New York. Our dedication, the number of hours we put in, because we have lower overhead, we can spend more time on each individual, festival has more value.’ And they may be right about that.

“But nobody thinks, ‘New York City Fringe is so much better than my festival they deserve what they get.’ They all think they have something to bring to the table that New York City Fringe doesn’t. So suddenly because one festival says, ‘I want to tax the author,’ now authors are getting taxed all across the nation. So we have to say something about it before it becomes a standard practice.”

* * *

Addressing some smaller items in the Dramatists Guild statement, there are several points that bear clarification.

- The Guild’s memo states, “It has been reported to us that the Fringe sent out its contracts to authors for this year’s festival at the end of July. If that is true, then it was a contract presented only a few weeks before the festival was scheduled to begin, after money has been raised and spent, leaving little or no time for authors and producers to assess their options in good faith.” Holy points out that all of the major terms of the agreements are included as part of the application process, so the terms should not come as a surprise, unless, in her words, “they didn’t read the information on the application before they submit.” However, Holy acknowledges the lateness of the agreements this year, saying, “I take full responsibility. We were trying to do everything electronically this year using DocuSign and I set it up so that the author’s agreement would fire when everyone had completed step one, the participants agreement and their W-9, and they haven’t all done that yet. That was a foolish way to set that up. So then I just gave up and e-mailed them a PDF.” Holy noted that this was a new process this year, replacing the previous practice of mailing paper contracts back and forth.

- The Dramatists Guild cites “the standard for fringe festivals around the world (including the US Association of Fringe Festivals, the Canadian Association of Fringe Festivals, and the Edinburgh Festival, the model on which most other festivals are based).” However, Jeff Larson, responding to an online inquiry by Arts Integrity to the US Association of Fringe Festivals, commented, “The USAFF is a loose affiliation of United States Fringes and does not enforce standards on its members.”

- The Guild noted, regarding the authors contract, that, “There are no obligations specified (either in the contract or the rules) for the Festival to support the show with any particular expenditure of marketing monies, nor any warrant of proper billing for the author and the play in whatever marketing and advertising the Fringe might do, and there is also no guarantee of mutually acceptable venues or performance schedules for the play, nor any discussion of the festival’s duties with regard to providing technical support.” As Holy noted above, those terms are included in the Participant Manual, an Appendix to the Participant Agreement. While the Guild concerns itself solely with the authors agreements, in the interest of transparency, FringeNYC might consider providing both the authors and participants agreements, as well as the participant manual, to the Guild so that all pertinent terms regarding production of the authors’ work are made clear.

* * *

So what of the FringeNYC terms regarding subsidiary rights, given the Guild’s characterization of prevailing practice and Holy’s acknowledgement that the terms cited were correct?

It is perhaps useful to look at the example of another New York summer festival, the New York Musical Festival, commonly referred to as NYMF, in operation since 2004 and the starting place for such musicals as Next To Normal and [title of show]. In 2010, NYMF sought to introduce a subsidiary rights clause to their agreements, saying in a statement:

Writers are the core beneficiaries of NYMF. Our goal is for NYMF shows to have future life, and for as many of our writers as possible to have their work produced again after the festival.

We specifically chose not to demand income from future third-party producers, as many other theater companies do, because doing so would encumber the project — making it less likely to be optioned or produced. Instead, we carefully structured our contract so that if — and only if — writers benefit substantially from NYMF’s support, they give back a small percentage so that we can provide similar opportunities to future generations of writers.

We think that’s fair.

Following a challenge by the Dramatists Guild to these new terms, NYMF withdrew its new terms in less than a month, writing in a statement:

The mission of NYMF is to support theatre artists, not to argue with them. We therefore withdraw our request to share in the subsidiary rights of authors participating in the 2010 Festival and will remove that section (Paragraph 5(E)) from our contract. Given the challenges of moving new musicals from the page to the stage and on to further productions, NYMF wants first and foremost to ensure that the shows we present have the unified support of the community.

While not working in the same kind of festival format, the O’Neill Theatre Center, one of the country’s oldest play development labs, also sought to introduce a subsidiary rights clause in 2006, at the start of the application process for the 2007 summer season. That effort drew a rebuke from Marsha Norman and Christopher Durang, the co-heads of the playwriting program at The Juilliard School at the time. A report from the New York Sun notes that the effort was quickly rescinded:

“We have their assurance that they will not this year, or in the future, be asking for a percentage of future royalties from the plays they accept for development,” Mr. Durang and Ms. Norman wrote. “They are looking for other sources of funding, but those monies will not come from your subsidiary rights.”

As the director of the Arts Integrity Initiative, I must step out of the third person to note that during my tenure as executive director of the O’Neill Theatre Center, from 2000 to 2003, I recall being charged by the board of directors to investigate the impact of introducing a subsidiary rights participation in authors’ future royalties. While I do not retain my notes from the time, I clearly remember my survey of prevailing practice, which consistently showed that regardless of whether I spoke with a festival, developmental, or producing organization, there was a clear dividing line for when it was appropriate to negotiate for subsidiary rights. That line was when a show was actually produced, not merely workshopped or showcased, even in cases where the work in question had been commissioned.

* * *

In conversation, Elena Holy noted that “we call ourselves presenters,” although in the context of explaining how the role of FringeNYC differs from the Edinburgh Fringe, she noted more direct involvement with productions than many presenters might have. In its Participant Agreement, which is signed by the designated liaison for each FringeNYC show, FringeNYC identifies itself as the “Presentor,” as distinct from a Producer (to which the Participant may be equivalent, even when the Participant is the producer, author and performer all in one). It is the Participant who is taking on primary responsibility for raising money, securing rehearsal space, assembling the show and delivering it to FringeNYC – the role of a Producer – and is even subject to penalties if it is unable to do so after a certain date, though they may not have continuing right to the show themselves. While FringeNYC does provide resources to each production and makes an investment of resources in them, mores than many fringe festivals, anecdotally the costs of producing the shows themselves, especially for companies not based in New York, can be considerably more than the FringeNYC allocation, once artist compensation, physical production, and travel and housing are factored in. In addition to the 2% subsidiary rights participation that FringeNYC asks of authors, it also asks for 2% of the Participants’ future revenues as well (again, over the $20,000 threshold).

While the discussion of Presentor, Presenter, Participant, Producer and so on may seem semantic, it’s not. Subsidiary rights typically accrue to producers who mount full productions of shows, at their expense (or with funds raised by them), whether commercial or not-for-profit, although the terms may vary. In Arts Integrity’s experience and in the examples given, they are not customary for productions which do not meet that standard. As for subsidiary rights granted by authors to entities responsible for the original mounting(s) of their play, for more than 25 years, there has been discussion of the complications engendered by encumbrances on authors when works receive several early productions that each secure (or demand) subsidiary rights. Providing them to developmental productions as well could have the effect of making it too expensive to produce a work that has promised multiple payments to multiple entities, or severely impede an author’s ability to be properly paid for subsequent productions. Additionally subsidiary rights are typically activated once a production has given a certain number of performances; as few as five are typically insufficient.

For 20 years, FringeNYC has been and continues to be an invaluable asset for new, inventive, irreverent and diverse work in New York. While it can’t hope to catch up with the longevity of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, it is deserving of a comparably long life. After the frenzy of the current festival subsides, FringeNYC would be well served to reconsider its policy regarding subsidiary rights, lest it prove an increasing impediment to the depth and breadth of work seen in its venues each summer. But precisely because the Fringe by its nature attracts younger or less established artists seeking a showcase in one of the world’s greatest theatre cities, with the possibility of being seen by industry and media professionals who could advance their shows, their careers, or both, it would do well not to ask more of its authors, its artists and its producers than any other fringe, showcase, workshop, reading series or the like. While many artists have enjoyed and benefited from the Fringe and have agreed to its longstanding terms, with the subsidiary rights language ultimately being activated for the very tiniest percentage, the Fringe’s embracing spirit can set an example for its artists and producers of what they can and should expect in the future, and that begins with their contracts.

June 27th, 2016 § § permalink

As a result of their quixotic effort to secure the first high school performance rights to Hamilton, Wexford Collegiate School of the Arts’s Hamilton videos drew a great deal attention earlier this month, perhaps as much for being pulled from YouTube than from their short life online. A CBC video about Wexford’s efforts to gain the attention of the Hamilton team remains online, even though it contains material that was otherwise withdrawn from circulation due to claims of copyright infringement. That video has been seen much more widely than the original Wexford videos were, racking up many hundreds of thousands of views after being posted to Facebook by the CBC.

As a result of their quixotic effort to secure the first high school performance rights to Hamilton, Wexford Collegiate School of the Arts’s Hamilton videos drew a great deal attention earlier this month, perhaps as much for being pulled from YouTube than from their short life online. A CBC video about Wexford’s efforts to gain the attention of the Hamilton team remains online, even though it contains material that was otherwise withdrawn from circulation due to claims of copyright infringement. That video has been seen much more widely than the original Wexford videos were, racking up many hundreds of thousands of views after being posted to Facebook by the CBC.

In the wake of the debate over the videos, Ann Merriam of Wexford Collegiate, who directed the Hamilton performances, responded to questions posed by Arts Integrity about the origin of the school’s Hamilton videos, and any public performances of the material. The questions were posed prior to the videos being removed from YouTube, with no anticipation that such action would necessarily take place.

Wexford students perform Hamilton on CityTV

Merriam said that the material from Hamilton was performed four times publicly, once at a show choir festival at the Etobicoke School for the Arts, once at a Benefit for Arts Education, and twice as part of the Wexford Variety Show. In addition to “Right Hand Man,” “Yorktown” and “Burn,” which appeared as videos, the songs “Alexander Hamilton,” “Guns and Ships,” and “You’ll Be Back” (identified by Merriam as “The King”) were also performed. In addition to the performance venues mentioned by Merriam, the students also performed on a program called “Breakfast Toronto” on the CityTV channel.

No specific budget for the performances was broken out by Merriam, who wrote, “Firstly, we are a public high school and don’t track costs by production. This project was all volunteers. I didn’t have any budget since it initially was not part of our programmed year.” However, Merriam did indicate that there were costume rentals both for the performances and for the video shoot (which was separate from the public performances), of “approximately $750-800” each time. In addition, Merriam wrote, “We paid $1,000 to a hip-hop artist to create original tracks.”

She explained that the cost of the rentals for the video shoot was covered by a group of parents from “People for Education,” since it fell outside of the school’s Variety Show activities. As for the director of the videos and the multiple choreographers, Merriam said they were all either volunteers or individuals who work regularly with the school on various assignments for small annual stipends. Approximately $1,200 was spent on equipment rentals for the video shoot.

Admission was charged to the Wexford Variety Show, where the six numbers were performed. Past shows have had a $20 (Canadian) ticket price. The 2016 price has not been confirmed. There were also tickets sold for the show choir event.

Given the furor that arose, there was commentary from many quarters. On the legal front, a post from Adam Jacobs, an attorney with Hayes eLaw in Toronto, was most helpful and informative, especially in regards to where US and Canadian copyright laws may differ. However, Jacobs was very clear about where Wexford had gone awry:

SOCAN’s tariffs do not, however, deal with the performance of a musical work in combination with acting, costumes and sets; these “grand rights,” which include many of the other protectable elements from Hamilton, would have to be licenced from the various creators of Hamilton. This leaves Wexford Collegiate in a scenario where, should they offer to pay the relevant SOCAN tariff to perform the musical compositions, they are able to publicly sing musical compositions from Hamilton, just without the accompanying characters, costumes, dialogue, staging or choreography….

Any reproduction of the Hamilton musical compositions, including any reproduction of the public performance of those musical compositions in order to post the video to YouTube, would require a private licencing agreement with the composer and music publisher….

Note, however, that even if one or more Canadian copyright exceptions were to apply, YouTube will apply American copyright law to determine whether there has been any infringement. It is likely that the US law would provide even less scope for the posting of such videos than Canadian law.

While Wexford Collegiate may have been ill-advised to perform musical compositions from Hamilton and post videos of the performances on YouTube, there were avenues available to the school to engage their students’ creativity while complying with Canadian copyright law.

The Dramatists Guild of America issued a statement on copyright in the wake of the Hamilton videos, without making specific comments about the Wexford situation. It read, in part:

When their work shows up in unauthorized productions, or on YouTube videos, it’s not just a matter of lost revenues. It is an infringement on the very nature of the dramatists’ authorship and a violation of their right to control their artistic expression. Even the non-commercial public use of their work by well-meaning fans, either on the internet or in amateur productions in their communities, can damage a show’s value in various markets, and it is a copyright violation under most circumstances. Most importantly, it undermines an author’s prerogative to decide when, where and how their work will be presented.

Finally, it is important to note that for every online commenter who castigated the Hamilton team for, apparently, asserting their copyright (“apparently” since the show has made no public statement on the situation to date), it seemed there was another commenter who took the students of Wexford to task, often quite unpleasantly, for their appropriation of copyrighted material. But what is clear from Merriam’s detailing of the context of the performances is that this was not a case of students going rogue, either in performing the material or sharing in hopes for more opportunity to perform Hamilton, but rather students participating in activities organized by and sanctioned by their school.

It is no surprise that the students were disappointed and confused when the videos were removed, because they were operating within the parameters they’d been given. Invective serves no purpose in clarifying this situation and bringing forward the proper practice for all to understand and learn from. Clearly that learning must come first for the faculty and administration of Wexford Collegiate, who from this point forward, will presumably operate within the guidelines of Canadian copyright law (and US law, where applicable) in all of the work presented by and at the school. Through them, successive classes of Wexford students must be taught what is and is not permissible, so that ultimately the students can preserve their own rights to earn a living from original work they create now and in the future.

CBC video about Wexford “Hamilton”

One final thought: as the school campaigned for attention, media outlets were, as is their nature, attracted to this story because it involved a hot show and talented kids. Save for the CBC, which acknowledged in its original report that these performances were unauthorized (but still embedded the YouTube videos and created their own from them), there seemed to be little thought by video, print or online outlets as to whether they were distributing material that violated copyright. Since they would presumably fight the appropriation of their own material, it’s a shame that reporters, editors and news directors didn’t look at this situation more critically, before playing a role in disseminating material that was not properly licensed for performance or recording.

April 8th, 2016 § § permalink

Priscilla Lopez in Pippin (Photo by Joan Marcus)

The recent laws passed by the states of North Carolina and Mississippi, which condone discrimination against LGBTQ citizens under the guise of religious freedom are, so far as I’m concerned, a national shame. That other states have attempted or will soon attempt to pass similar legislation is frightening. I can only hope that these decisions will be swiftly challenged, taken to the supreme court, and repealed as unconstitutional.

Composer and lyricist Stephen Schwartz, known internationally for his work on, to name but three, Godspell, Wicked and Pippin, shares this opinion. He has used his platform as one of musical theatre’s most successful living artists to express his dismay: in the wake of the North Carolina decision, which came first, Schwartz announced that he would not permit the licensing or production of any of his works in that state so long as this law remains in place. Decrying the passage of HB2, as it is known, he compared his action to the boycotts undertaken against South Africa over apartheid.

While I saw numerous artists praising Schwartz online through social media, I also saw the response from theatres in North Carolina, who were concerned that a cultural boycott of their state might have minimal effect on their elected leaders, while denying works to a community that is predisposed to oppose the law. Angie Hays, the head of the North Carolina Theatre Conference, issued a statement in which she said her organisation has been in contact with “artists and producers from across the country who are asking how they can most effectively play a part in lifting up the NC theatre community so that we may continue to produce work that will open hearts and change minds.” In a letter to The Hollywood Reporter, Schwartz, in his second statement, said that his decision wasn’t singular, citing “a collective action by a great many theatre artists.”

As I write, based on news reports and my own conversations with the heads of several theatrical licensing houses, only one author (Tom Frye) beyond Schwartz’s own collaborators has joined him in placing a moratorium on his work in North Carolina. Ralph Sevush, executive director for business affairs at the Dramatists Guild, which represents the majority of playwrights and composers in the US, said in a statement that the guild itself “cannot call for or support boycotts, as a matter of law. However, even though the guild represents writers with divergent views, the guild is unified in supporting Stephen’s right to exercise control over the licensing of his work in whatever manner he deems appropriate.”

There is, I have no doubt, a great deal of conversation about how to respond to these loathsome laws at theatres, at dance companies, at orchestras and so on, and a prevailing unanimity in despising these decisions. But as is so often the case in the early days of a crisis, there is no consensus about how to combat it, either within North Carolina and Mississippi, or nationwide. If more and more works are denied, will theatres in North Carolina, and presumably in Mississippi, reach a point at which their creative decisions are truly constrained? Does stage work in these states rise to a level that will become meaningful to legislators, or will it stand in the shadow of major commercial interests, who have the scale and the economic power to sway policy?

Like Sevush from the Dramatists Guild, I absolutely support Schwartz’s right to make decisions regarding his own works. At the same time, I worry about the health of theatres in these states under these new regulations, at a time when they can be centres of opposition to HB2, by doing what theatre does so well, which is to teach empathy. In addition, even if they won’t be doing so on stages in these battleground states, I like to think that Charlemagne’s son, who renounced war and sin, that the Jesus who once wore Superman’s logo on his chest, and that the misunderstood green girl from Oz are on the ground there nonetheless, fighting the essential fight against bias and hate. Because we need every voice, real and fictional, to speak out and sing out as well.

November 16th, 2015 § § permalink

Poster for Jesus in India at Clarion University

“What will you learn?” asks the home page of the website of Clarion University in Pennsylvania. In the wake of the school’s handling of the casting of white students in Asian roles in Lloyd Suh’s Jesus in India, and the playwright’s withdrawal of production rights upon learning this fact, it’s unclear at best, disturbing at worst, to consider what Clarion wants students to learn about race and about the arts.

Based on what is appearing in the press, they are learning to blame artists for wanting to see their work represented accurately. They are learning to attack artists when the artists defend their work. They are learning that a desire to see race portrayed with authenticity is irrelevant in an academic setting. They are learning that Clarion seems unaware of the issues that have fueled racial unrest on campuses around the country, most recently with flashpoints at the University of Missouri and Yale University. They are learning that when a community is overwhelmingly white, concerns about race aren’t perceived as valid.

In an essay published in the Chronicle of Higher Education on Friday, Marilouise Michel, professor of theatre and director of the canceled production, wrote, “I have intentionally left out the name of the playwright and the piece that we were working on as I do not wish to provide him with publicity at the expense of the fine and viable work of our students.” What’s peculiar about that statement is that until 1:30 pm that day, when he released a statement, the playwright hadn’t sought for this issue to be public in any way. It was Clarion that had contacted the press, Clarion which had released his correspondence with Michel, and Clarion which used a professional public relations firm to issue a statement about the situation from the university and its president. It reads, in part:

The university claims their intent from the start was to honor the integrity of the playwright’s work, and the contract for performance rights did not specify ethnically appropriate casting. Despite the university’s attempt to give Suh a page in the program to explain his casting objections and a stage speech given by a university representative on the cast’s race, Suh rejected any solutions other then removing the non-Asian actors or canceling the production.

“We have no further desire to engage with Mr. Suh, the playwright, as he made his position on race to our theater students crystal clear,” says Dr. Karen Whitney, Clarion University President. “I personally prefer to invest my energy into explaining to the student actors, stage crew and production team members why the hundreds of hours they committed to bringing ‘Jesus in India’ to our stage and community has been denied since they are the wrong skin color

This insidious inversion of racial justice is profoundly troubling. The play, set in India, has three characters named “Gopal,” “Mahari/Mary,” and “Sushil,” a strong indication of their race. Suh maintains that the university was asked about their plans to cast those roles, and his agent Beth Blickers says no answer was ever given. But when the playwright finally drew a line over racial representation, he was the one who was supposedly denying skin color, when it was Michael’s personal interpretation of the play, against clear evidence and requests, which was ignoring race in the play. So now, one must wonder whether Dr. Whitney will be spending time explaining to the students of color on campus why she is vigorously defending the practice of “brownface” on campus (white actors portraying Indian characters, regardless of whether color makeup is actually employed) and attacking a playwright of color for decrying the practice.

To be clear, there is undoubtedly great disappointment and pain among the students and crew who had been working on the production. Anyone in the arts will surely sympathize with them for having invested time and effort towards a production that they surely undertook with the best of intentions. But they were, most likely unwittingly, made complicit in the act of denying race and denying an artist’s wishes.

In the university’s press release, the extremely small Asian population of the school is noted (at 0.6% of the student body), as it has been previously in many reports. That no Asian students auditioned should not have been surprising, nor should it have been license to substitute actors of others races as a result. Any director who is part of an academic theatre program has a very good idea of what talent may be available, and often productions are chosen accordingly. So it is not the failure of Asian students to audition to blame for the inaccurate racial casting. More correctly it was the decision to produce a play which clearly called for Asian characters and the assessment that race didn’t matter that created this situation – not Lloyd Suh or any student.

In the Chronicle, Harvey Young, chair of the theatre department at Northwestern University, admittedly a more urban school, says the following regarding racial casting on campus:

“That is the magic of the university — to introduce people to a variety of perspectives and points of view.”

But at Northwestern, Mr. Young said, the department uses a variety of strategies to avoid what could be racially problematic casting. The department has hired outside actors to play some roles and serve as mentors to students, reached out to minority groups to let them know about acting opportunities, and staged readings at which only voices are represented.

“The goal is to devise strategies that allow you to engage the work while being aware of whatever limits exist,” Mr. Young said.

In her essay for the Chronicle, Michel wrote, “Perhaps Shakespeare would wince at a Western-style production of The Taming of the Shrew, but he never told us we couldn’t. He never said Petruchio couldn’t be black, as he was in the 1990 Delacorte Theater production starring Morgan Freeman.” This is a specious and rather ridiculous argument, since Shakespeare’s work is not under copyright and can be cast or altered in any way one wishes. While there are certainly examples of actors of color taking on roles written for or traditionally played by white actors – NAATCO’s recent Awake and Sing with an all-Asian cast playing Clifford Odets’s Jewish family, the Broadway revival of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof with a black cast playing Tennessee Williams’s wealthy southern family – they were done with the express approval of the rights holders. That these productions were in New York as opposed to Clarion, Pennsylvania makes no difference as to the author’s rights. What we have not seen is an all-white Raisin in the Sun, either because no one has been foolish enough to attempt it or because the Lorraine Hansberry estate hasn’t allowed it.

Clarion’s press efforts have certainly paid off in the local community, with three news/feature stories in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (here, here and here) as well as an editorial, along with two features (here and here) in the Chronicle of Higher Education, in addition to the aforementioned essay. That the Post-Gazette’s editorial sides entirely with Clarion is no surprise, since the university was driving the story; that it fails to take into account any reporting which runs counter to Clarion’s narrative, and indeed repeats them, is shameful, a disservice to the Pittsburgh community. That the Chronicle of Higher Education ran Professor Michel’s essay, another one-sided account of the situation, is problematic, but the headline (whether it is theirs or Michel’s), “How Racial Politics Hurt My Students,” is a clarion call for paranoia about race. It ignores the fact that the problems arose from a failure to respect the work and the playwright, that the issue is based not in politics, but in art, and that the author saw his work being defaced and stood up for it. There have been countless other reports on the situation. That this has engendered vile racist outpourings online, especially in comments sections and on Facebook, and in some press accounts is the result of the university’s irresponsible spin.

Universities are in no way exempted from professional standards when it comes to licensing and producing shows; to claim otherwise is to suggest that campuses are bubbles in which the rules of the real world do not apply. While classrooms are absolutely places for exploration and discovery, theatre productions of complete works for audiences are not just educational exercises. Students need to be taught creative and legal responsibility towards plays (and musicals) and their authors, not encouraged to take scripts as mere suggestions to be molded in any way a director wishes. When it comes to race, this incident and the recent Kent State production of The Mountaintop will now insure that every playwright who cares about the race of their characters will be extremely explicit in their directions, but that doesn’t excuse directors who look for loopholes to justify willfully ignoring indications in existing texts.

It’s my understanding that there has been new contact between Michel and Suh, though I am not party to its nature or content. It’s worth noting that in the third Post-Gazette story, it is reported that “Ms. Michel took to Facebook Saturday to ask “that any negative or mean-spirited posts or contact towards Mr. Suh be ceased. We are both artists trying to serve a specific community and attacking him helps no one.” That’s a responsible position to take, but it should be expanded to include negative posts or contact about the accurate portrayal of race in theatre, since they are flourishing in the wake of this incident.

It is also now time for the university to explain the truth about why the production was shut down, namely a failure to respect the artistic directive of the playwright; insure that this incident and the rhetoric surrounding it hasn’t been a license for anyone to marginalize their students of color; and begin truly addressing equity and diversity on their campus. Regardless of the racial makeup of their community or student body, they need to be setting an example and creating a better environment for all students, not feeding into narratives of racial divisiveness.

Update, November 18, 7 pm: Earlier today, the Dramatists Guild of America released a statement regarding the organization’s position on casting and copyright, signed by Guild president Doug Wright. It reads, in part:

One may agree or disagree with the views of a particular writer, but not with his or her autonomy over the play. Nor should writers be vilified or demonized for exercising it. This is entirely within well-established theatrical tradition; what’s more, it is what the law requires and basic professional courtesy demands.

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts and director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School College of Performing Arts School of Drama.

October 16th, 2015 § § permalink

“Is there a link for this so I can read the whole thing if there’s more?”

“Is there a link for this so I can read the whole thing if there’s more?”

“Maybe this wants to grow up and become a blog post?”

“I’ve been encouraging him to do so!!!!”

“This, I feel, is not just a statement for theater folk, but a life statement, a ‘how are you living in the world’ statement.”

The quotes above have all been written in the past 24 hours or so in response to a comment I made on Facebook – not a blog post, not an essay, but a comment, although admittedly not a short one. The response is gratifying, even as I feel awkward about repeating some of the positive remarks it engendered.

I share them because there’s been a lot of likes and shares and comments for a short burst I essentially blurted out on Wednesday afternoon, after seeing an array of responses to American Theatre editor Rob Weinert-Kendt’s apology for aspects of his Monday post about The Mikado and the heinous practice of yellowface. My comment was not about either of Rob’s pieces, but rather some of the defenses of yellowface that they elicited, and outright attacks on those who seek to abolish it. I stand, as I made clear several weeks ago in my own blog post, with the latter group.

Much as I stare at my comment, I don’t see how I can expand it. It addresses multiple issues on which I speak and write frequently, composed directly in one of those Facebook comment boxes, borne of anger and empathy, effective in its terseness. I feel that trying to elaborate upon it will only reduce it, though I appreciate the appeals of those who would like there to be more. I have to thank my friend and colleague Jacqueline Lawton, who lifted it out of the comments section and reiterated it as a Facebook post on her timeline, for getting it more attention that it would have otherwise received.

Because the Facebook algorithm is a mercurial beast, and it’s impossible to know who may have seen the comment, or how long it will be floating around in people’s feeds, I share it now, unedited, primarily as a means of preserving a relatively off-the-cuff cri de coeur – despite my concerns, that in my haste, I did not properly differentiate between my use of the terms “race” and “ethnicity,” even though I should know better.

“One of the great fallacies employed by those who resist making the American theatre more diverse is that when opening up traditionally or even specifically white roles to people of color, it should be a two way street – that if black, API, Latino, and Native Americans can play Willy Loman or Hedda Gabler, white actors should be able to perform in the works of August Wilson. That’s nonsense. The whole point of diversifying our theatre is not to give white artists yet more opportunities, but to try to address the systemic imbalance, and indeed exclusion, that artists of color, artists with disabilities and even non-male artists have experienced. Of course, when it comes to roles specifically written for POC, those roles should be played by actors of that race or ethnicity – and again, not reducing it to the level of only Italians should play Italians and only Jews should plays Jews, but that no one should be painting their faces to pretend to an ethnicity which is obviously not theirs, while denying that opportunity to people of that race. To those who would claim that our theatre isn’t centered around white men, look no further than the results of the Dramatists Guild’s The Count, which shows that four out of every five plays produced in America is by a white man. As for those who charge racism on the part of people striving for equality in the 21st century, I would suggest you don’t fully appreciate the racial struggles that have been part of this country’s original sin since Europeans began eradicating Native Americans and forcibly bringing Africans to these shores as slaves. Perhaps those in theatre can’t ever hope to directly redress this history, but we can at least seek to model a better world in our work and on our stages. And certainly we can do better than to engage in ad hominem attacks and threats against others in our field who seek equality.”

Will I say more on this subject? Absolutely. It’s become very central to my belief about the world of the arts, and the world at large. But as someone who usually goes on too long about just about everything, I’d like to stick with atypical brevity, hoping it provokes more conversation, more writing, more thinking about how we can all do better at embracing everyone who seeks a role in the arts. And if my few sentences above prove at all useful, they’re yours to employ in the good fight for diversity and inclusion.

P.S. Because advocates can have a tendency to become single-minded and even humorless in their pursuits, I must share with you my favorite response to my squib of a doctrine, among the many I read, courtesy of the dreaded auto-correct: “Wow! That’s it in a buttshell!!”

Howard Sherman is interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts.

February 24th, 2015 § § permalink

Last night, I was extremely flattered and honored to receive the second annual Dramatists Legal Defense Fund’s “Defender” Award, for my work on behalf of artists’ rights and against censorship. My remarks were fairly brief (I know a little something about brevity and awards presentations, even when there isn’t an orchestra to “play you off”), so for those who have expressed interest, or may be interested, here’s what I had to say, following a terrific and humbling introduction by playwright J.T. Rogers, my newest friend.

Last night, I was extremely flattered and honored to receive the second annual Dramatists Legal Defense Fund’s “Defender” Award, for my work on behalf of artists’ rights and against censorship. My remarks were fairly brief (I know a little something about brevity and awards presentations, even when there isn’t an orchestra to “play you off”), so for those who have expressed interest, or may be interested, here’s what I had to say, following a terrific and humbling introduction by playwright J.T. Rogers, my newest friend.

I feel as if this evening is a classic Sesame Street segment, because as I see my name alongside those of such great talents as Annie Baker, Jeanine Tesori, Chisa Hutchinson, Charles Fuller and my longtime friend Pete Gurney, I can’t help feeling that one of these things is not like the others, one of these things doesn’t belong, namely me.

That said: I am honored more than you can possibly know to receive this recognition from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund and the Dramatists Guild, because I have spent the better part of my life in the dark with your stories, your characters, your words and your music, and my life is so much better for it.

My efforts on behalf of artists rights and against censorship began, four years ago, in what I merely thought was one blog post among many. My awareness and understanding has evolved significantly over that time. I am asked sometimes why I think there is so much more censorship of theatre now, and I’m quick to say that I know this has been happening for years, for decades; all I have done is, perhaps, to make some people more aware of some of the incidents, and to try to address them in greater depth than they might have otherwise received.

I think the same is true of unauthorized alteration of your work, sad to say. All I’ve been able to do is call more attention to it, in the hope of warning people off from trying it ever again. It is an uphill battle.

I want to thank John Weidman, Ralph Sevush and everyone who is part of creating the DLDF for giving me this honor, and to thank the Guild for being my partner and for welcoming me as your partner in these efforts. I want to thank Sharon Jensen and the staff and board of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts for allowing me the latitude to address these situations as they have arisen in the 18 months I have been part of that essential organization. I want to thank David van Zandt, Richard Kessler and especially Pippin Parker for making it possible for me to professionalize this work as the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama; I look forward to working with all of you through that new platform. And I especially want to thank my wife, Lauren Doll, for so many things, not least of which has been tolerating the late night and early morning calls with strangers around the country, often high school students, and the furious typing at all hours, whenever someone reaches out to me about censorship or the abrogation of authors rights.

I accept this award less for myself than for the students, teachers and parents who stand up for creative rights, in places like Maiden, North Carolina; South Williamsport, Pennsylvania; Plaistow, New Hampshire; Wichita, Kansas; and Trumbull, Connecticut, among others. If they didn’t sound the alarm, we might otherwise never know.

I should tell you that when I’ve visited some of these communities, I have had people come up to me repeatedly and tell me that I am brave for doing this work. ‘But I’m not brave,’ I tell them, ‘You’re the brave ones. I have nothing at stake here. You do.’

Indeed, I am not brave. What I am is loud. I will shout on behalf of theatre, on behalf of arts education, on behalf of creative challenge, on behalf of all of you here and all of those artists who aren’t here for as long I have a voice. And those of you who know me are fully aware that it’s very hard to shut me up.

My congratulations to tonight’s other honorees and thank you again for this award.

February 10th, 2015 § § permalink

Hannah Cabell and Anna Chlumsky in David Adjmi’s 3C at Rattlestick Playwrights Theater (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Seen any good productions of David Adjmi’s play 3C lately?

Sorry, that’s a trick question with a self-evident answer: of course you haven’t. That’s because in the two and a half years since it premiered at New York’s Rattlestick Playwrights Theater, no one has seen a production of 3C because no one is allowed to produce it, or publish it. Why, you ask? Because a company called DLT Entertainment doesn’t want you to.

3C is an alternate universe look at the 1970s sitcom Three’s Company, one of the prime examples of “jiggle television” from that era, which ran for years based off of the premise that in order to share an apartment with two unmarried women, an unmarried man had to pretend he was gay, to meet with the approval of the landlord. It was a huge hit in its day, and while it was the focus of criticism for its sexual liberality (and constant double entendres), it was viewed as lightweight entertainment with little on its mind but farce and sex (within network constraints), sex that never seemed to actually happen.

Looking at it with today’s eyes, it is a retrograde embarrassment, saved only, perhaps, by the charm and comedy chops of the late John Ritter. The constant jokes about Ritter’s sexual façade, the sexless marriage of the leering landlord and his wife, the macho posturings of the swinging single men, the airheadedness of the women – all have little place in our (hopefully) more enlightened society and the series has pretty much faded from view, save for the occasional resurrection in the wee hours of Nick at Night.

In 3C, Adjmi used the hopelessly out of date sitcom as the template for a despairing look at what life in Apartment 3C might have been had Ritter’s character actually been gay, had the landlord been genuinely predatory and so on. It did what many good parodies do: take a known work and turn it on its ear, making comment not simply on the work itself, but the period and attitudes in which it was first seen.

Enter DLT, which holds the rights to Three’s Company. They sent a cease and desist letter to Adjmi back in 2012 claiming that the show violated their copyright; Adjmi said he couldn’t afford to fight it. Numerous well-known playwrights wrote a letter in support of Adjmi and the controversy generated its first wave of press, including pieces in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Over time, there have been assorted legal filings by both parties, with another wave of press appearing last year just about this time, when Adjmi sued for the right to reclaim his play for production, with commensurate press coverage once again from the Times and Studio 360, among others.

Enter DLT, which holds the rights to Three’s Company. They sent a cease and desist letter to Adjmi back in 2012 claiming that the show violated their copyright; Adjmi said he couldn’t afford to fight it. Numerous well-known playwrights wrote a letter in support of Adjmi and the controversy generated its first wave of press, including pieces in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Over time, there have been assorted legal filings by both parties, with another wave of press appearing last year just about this time, when Adjmi sued for the right to reclaim his play for production, with commensurate press coverage once again from the Times and Studio 360, among others.

Why do I dredge this all up now? Because the bottom line is that DLT is doing its level best to prevent a playwright from earning a living, and throwing everything they can into a specious argument to do so. They say, both in public comments and in their filings, that 3C might confuse audiences and reduce or eliminate the market for their own stage version (citing one they commissioned and one for which they granted permission to James Franco). They cite negative reviews of 3C as damaging to their property. And so on.

But while I’m no lawyer (though I’ve read all of the pertinent briefs on the subject), I can make perfect sense out of the following language from the U.S. Copyright Office, regarding Fair Use exception to copyright (boldface added for emphasis):

The 1961 Report of the Register of Copyrights on the General Revision of the U.S. Copyright Law cites examples of activities that courts have regarded as fair use: “quotation of excerpts in a review or criticism for purposes of illustration or comment; quotation of short passages in a scholarly or technical work, for illustration or clarification of the author’s observations; use in a parody of some of the content of the work parodied; summary of an address or article, with brief quotations, in a news report; reproduction by a library of a portion of a work to replace part of a damaged copy; reproduction by a teacher or student of a small part of a work to illustrate a lesson; reproduction of a work in legislative or judicial proceedings or reports; incidental and fortuitous reproduction, in a newsreel or broadcast, of a work located in the scene of an event being reported.”

As someone who has gone out on a limb at times defending copyright and author’s rights, I’d be the first person to cry foul if I thought DLT had the slightest case here. But 3C (which I’ve read, as it’s part of the legal filings on the case) is so obviously a parody that DLT’s actions seem to be preposterously obstructionist, designed not to protect their property from confusion, but to shield it from the inevitable criticisms that any straightforward presentation of the material would now surely generate.

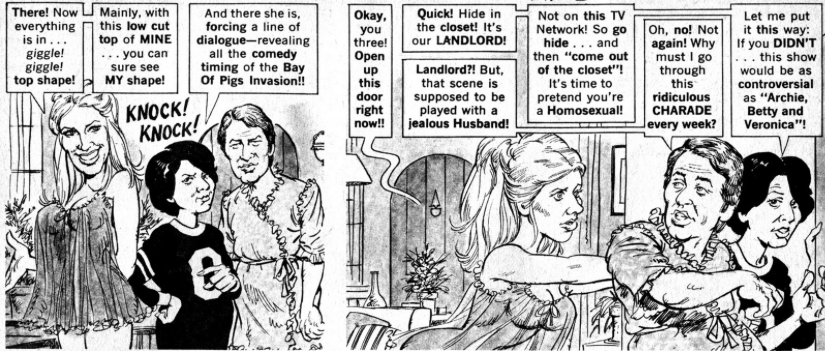

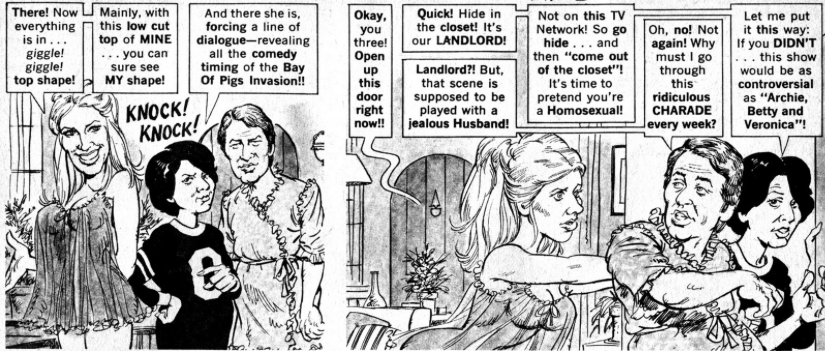

Rather than just blather on about the motivations of DLT in preventing Adjmi from having his play produced and published, let me demonstrate that their argument is specious. To do so, I offer the following exhibit from Mad Magazine:

What’s fascinating here is that Mad, a formative influence for countless youths in the 60s and 70s especially, parodied Three’s Company while it was still on the air, seemed to already be aware of the show’s obviously puerile humor, was read in those days by millions of kids – and wasn’t sued for doing so. That was and is a major feature of Mad, deflating everything that comes around in pop culture through parody. The fact is, Adjmi’s script is far more pointed and insightful than any episode of Three’s Company and may well work without deep knowledge of the original show, just like the Mad version.

The most recent filing in the Adjmi-DLT situation comes from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, an offshoot of The Dramatists Guild. Like all of the filings in this case, it’s very informative about copyright in general and parody in particular, and it spells out the numerous precedents where the use of a prior work was permitted under fair use, with particular attention to the idea that when the new work is transformative – which 3C surely is – it is permitted (read the complete amicus curiae brief here). In addition to their many examples, I would add from my own misspent youth such works as Bored of the Rings, a 1969 book-length parody of Tolkien by some of the people who would go on to create the National Lampoon, where incidentally, DLDF president John Weidman exercised his own comic skills) and Airplane!, which took its plotline (and punctuation mark) of a poisoned airline crew directly, uncredited, from the 1957 film Zero Hour! More recently, the endlessly touring Potted Potter has successfully run without authorization, though clearly derived from the works of J.K. Rowling and prior to any authorized stage interpretation.

The most recent filing in the Adjmi-DLT situation comes from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, an offshoot of The Dramatists Guild. Like all of the filings in this case, it’s very informative about copyright in general and parody in particular, and it spells out the numerous precedents where the use of a prior work was permitted under fair use, with particular attention to the idea that when the new work is transformative – which 3C surely is – it is permitted (read the complete amicus curiae brief here). In addition to their many examples, I would add from my own misspent youth such works as Bored of the Rings, a 1969 book-length parody of Tolkien by some of the people who would go on to create the National Lampoon, where incidentally, DLDF president John Weidman exercised his own comic skills) and Airplane!, which took its plotline (and punctuation mark) of a poisoned airline crew directly, uncredited, from the 1957 film Zero Hour! More recently, the endlessly touring Potted Potter has successfully run without authorization, though clearly derived from the works of J.K. Rowling and prior to any authorized stage interpretation.

It’s been months since there have been filings for summary judgment in the case (August 2014, to be precise), and according to Bruce Johnson, the attorney at Davis Wright Tremaine in Seattle who is leading the fight on Adjmi’s behalf, there is no precise date by which there will be a ruling. Some might say that I’m essentially rehashing old news here, but I think it’s important that the case remains prominent in people’s minds, because it demonstrates the means by which a corporation is twisting a provision of copyright law to prevent an artist from having his work seen – and that’s censorship with a veneer of respectability conferred by legal filings under the umbrella of commerce. There may be others out there facing this situation, or contemplating work along the same lines, and this case may be suppressing their work or, depending upon the ultimate decision, putting them at risk as well.

We don’t all get to vote on this, unfortunately. But even armchair lawyers like me can see through DLT’s strategy. I just hope that the judge considering this case used to read humor magazines in his youth, which should provide plenty of precedent above and beyond what’s in the filings. 3C may take a comedy and make it bleak, but there’s humor to be found in DLT’s protestations, which are (IMHO) a joke.

P.S. I don’t hold the copyright to any of the images on this page. I’m reproducing them under Fair Use. Just FYI.

June 20th, 2014 § § permalink

“First, let’s define what we mean by ‘changes’.”

Hands on a Hardbody at Houston’s Theatre Under The Stars

This statement came up not once but twice in my conversation with Bruce Lumpkin, artistic director of Houston’s Theatre Under The Stars and director of their current production of the musical Hands on a Hardbody. The comment arose when I asked Lumpkin specific questions about my communications with Hardbody creators Amanda Green and Doug Wright. Green, who attended the show’s opening at TUTS, detailed a fairly extensive list of alterations to the musical, none of which had been discussed with the authors or their licensing house prior to production.

[I should note from the outset that I was first made aware of the authors’ concerns by Bruce Lazarus, executive director of Samuel French, which licenses the show. He reached out to me because of my prior writing on the subject of authors’ rights and because we know each other from my one-year tenure in 2012-13 on the Samuel French advisory committee (two meetings; $500 total honorarium). I say this by way of full disclosure.]

Having attended the opening night of Hardbody at Lumpkin’s invitation, Green described to me her experience in watching the show. “They started the opening number and I noticed that some people were singing solos other than what we’d assigned. As we neared the middle of the opening number, I thought, ‘what happened to the middle section?’” She said that musical material for Norma, the religious woman in the story, “was gone.”

Having attended the opening night of Hardbody at Lumpkin’s invitation, Green described to me her experience in watching the show. “They started the opening number and I noticed that some people were singing solos other than what we’d assigned. As we neared the middle of the opening number, I thought, ‘what happened to the middle section?’” She said that musical material for Norma, the religious woman in the story, “was gone.”

When the second song began, Green recalls being surprised, saying, “I thought, ‘so we did put this number second after all’ before realizing that we hadn’t done that.” As the act continued, Green said, “I kept waiting for ‘If I Had A Truck’ and it didn’t come.” She went on to detail a litany of ways in which the show in Houston differed from the final Broadway show, including reassigning vocal material to different characters within songs, and especially the shifting of songs from one act to another, which had the effect of removing some characters from the story earlier than before. She also said that interstitial music between scenes had been removed and replaced with new material. Having heard Green’s point by point recounting of act one changes, I suggested we could dispense with the same for act two.

Hands on a Hardbody on Broadway

When I asked Lumpkin about the nature of changes to the show. His response was, “I didn’t change lyrics, I didn’t change songs, I didn’t change dialogue. I only changed their order.” In response to my query as to why he felt he could make such shifts, Lumpkin cited having seen the show twice on Broadway and having seen the running order of songs as printed in the program each time differing, in addition to yet other song rundowns on inserts to the program.

“I thought that perhaps maybe I could put together a different order thinking that perhaps if they don’t like it I’ll put it back,” said Lumpkin. “There was no new vision for the show. It was just a matter of the order of the songs in the show. I knew there was a possibility they wouldn’t like it. I was totally upfront.”

Had he notified the authors or the licensing house in advance? “I guess I didn’t. I didn’t think changing the order with them coming [to the opening]. It wasn’t like cutting a number.” He continued, “I’ve done a lot of this before. I did this with Stephen Schwartz and Charles Strouse on Rags and they worked with me. But in that case it was about cutting some subplots and characters. When we did Godspell, I told Stephen Schwartz that the song order was kind of arbitrary and he let me work with it.”

I asked Lumpkin whether he would have made any changes to Hardbody, which he said he did over three days only after rehearsals had begun, if none of the authors had accepted his invitation to the opening. “Probably not,” he replied. “I wasn’t trying to reinvent the wheel. The only struggle they had was the order.” When I asked how he knew of the author’s “struggle,” he once again cited the various song lists he’d seen when attending the show on Broadway.

Lumpkin also suggested that there was some discrepancy between the score and the text he received, saying such things were common with licensed works. When I asked, “Did you ask for clarification from the source?” he responded, “No, I don’t think I’ve ever done that. I take their source material and we figure it out on our own.”

Hands on a Hardbody at Houston’s Theatre Under The Stars

Noting that I was asking a pointed question, I inquired, “Having signed a license agreement for the show, did you believe you had the legal and ethical right to make the changes you did?” Lumpkin declined to answer. But as we concluded our talk, he said that he knows how the authors feel, saying that he too had done original shows.

“I didn’t think that moving four numbers was a big deal. We’ve changed it back and I don’t think anyone in the audience knows the difference. Except me.”

However, Green had pointed out that opening night was also a press night. “He can say it can be turned back,” observed Green, “but it was already being reviewed that night.” And she clearly differs as to the extent of the changes.

Describing her post-show conversation with Lumpkin in Houston, Green says, “When it was over, I was flabbergasted. I had been planning to go to the cast party, but I couldn’t. Bruce came over to me and said, ‘I know you’re mad and I know you hate it, but you know it works better’.” Green continued: “He was pressuring me to make a decision and say I liked it. So I left.”

Green says she asked why Lumpkin hadn’t asked for permission and described his reply as, “He said he wanted to surprise us. He said the show wasn’t working at all.”

Describing her conversation with Doug Wright and their collaborator Trey Anastasio subsequent to seeing the show, Green said, “We wanted to have our show as written. We’d spent years building and honing it and had very specific character-driven moments. People didn’t just say things. We carefully crafted the show. We were taken aback and dismayed by his [Lumpkin’s] lack of respect and regard for copyright laws and our material.”

In response to a series of e-mailed questions about the changes as reported by Green, Doug Wright wrote, “I was stunned, especially because the changes were so egregious.” But because he hadn’t seen them firsthand, I asked him what he hoped directors and artistic directors might learn from the liberties taken with Hardbody at the outset of the short (June 12 to 22) TUTS run.