As headlines go, “A challenge for the arts: Stop sanitizing and show the great works as they were created” embodies what many of us were taught in school about the well-made essay: tell people what you’re going to tell them, offer support for your thesis, then tell them what you’ve told them. Unlike many instances where newspaper headlines misrepresent the content of the article that follows, I would say that Philip Kennicott’s article in The Washington Post on October 4th was accurately summarized. As a result, the unsettled feeling I had upon reading it remained with me as I read the piece itself, and long afterwards.

To select two paragraphs which explicitly reinforce Kennicott’s thesis, I offer first:

Censoring art to make it more palatable to contemporary audiences warps our sense of goodness, making our tolerance seem magically delivered rather than hard-won through centuries of struggle. It erases the complex, chaotic history of tolerance, especially problematic at a moment in history when the West is given to lecturing the “rest” on new and culturally alien extensions of compassion and decency across gender, sexual and sectarian lines.

Later in the piece, Kennicott asserts:

To preserve their independence, the arts need to stand resolutely aside from the increasingly complex rituals of giving and taking offense in American society. The demanding and delivering of apologies, the strange habit of being offended on behalf of other people even when you’re not personally offended, the futile but aggressive attempt to quantify offensiveness and demand parity in mudslinging — this is the stuff of degraded political discourse, fit only for politicians, partisans and people who enjoy this kind of sport.

I’m troubled by Kennicott’s charge that the arts in some way fail when they demonstrate sensitivity to prevailing social attitudes. While there are certainly many great works of art that contain misogynistic, racist, and classist attitudes (to name but three), to present them today and excuse them from criticism simply because they are “great” fails to in any way address how society has advanced when addressing inclusion, diversity and equality in the arts. It’s no small matter that the majority of the great works of the Western arts canon were also written by white men, and while that doesn’t negate their value, presenting them as if preserved in amber can be not only profoundly offensive but artistically stultifying.

I don’t happen to take to reworkings of classic works simply in order to fend off complaint; erasing the n-word from Huckleberry Finn struck me as patently absurd when a new edition doing just that appeared a few years ago. By way of example, the same holds true for productions of To Kill A Mockingbird which would eradicate that same word. In both cases, it’s a disservice both to the work and those who consume it. Frankly, I also don’t believe that any work should be, in total, deemed off limits because of changing mores.

But this conversation isn’t as binary as Kennicott presented, a choice between fidelity or censorship. Whether considering a work taught in classrooms or presented professionally on stage, one also has to factor in the interpretation and context, both separately and together.

There are many Jews who think The Merchant of Venice should never be performed, due to its ant-Semitic elements; I don’t happen to share their opinion. I would however be troubled to find a production that takes to heart the classification of the play as one of Shakespeare’s comedies, playing the shaming of Shylock for boisterous laughs. I know many people who feel the same way about The Taming of the Shrew, but a production by Mark Lamos at Yale Rep some years ago, featuring an all-male Latino cast, took the casual misogyny of the play, once seen as comic, and transmuted it into an exploration of modern male sexual identity, holding the play at a distance to be examined through a modern framing device, rather than asking us to accept the humbling of Kate as a just dénouement. Given the volume of Shakespeare productions every year, I imagine there are numerous interpretations which don’t bowdlerize the language, but instead imbue the plays with new insight; the Donmar Warehouse’s all-female Julius Caesar and Henry IV surely are important examples.

As I contemplated this issue, I happened upon online information about a South African production of The Magic Flute by the Isango Ensemble, currently touring the U.S., which has an all-black cast; this presumably immediately alters the perception of the blackamoor Monostatos, who Kennicott used as a key discussion point. At the same time, I was reading a great deal about the Metropolitan Opera’s imminent production of The Death of Klinghoffer, which is at the center of enormous controversy over its depiction of an incident from the real historical past, but on which I can offer no opinion because I haven’t seen it; the controversy only points up the fact that it isn’t solely works from the distant past which can provoke.

Citing counter-examples production by production would be endless, so let me turn to the issue of context. When a class is taught or a company produces a work whose social attitudes reflect less enlightened views, it’s worth noting whether any framing is provided, for students or audience. If a teacher assigned Huckleberry Finn without prior discussion and comprehensive followup, I would question their tact and their skills; to foist the book on students sans preface would, I imagine, be very upsetting to students. The same holds true for reading or seeing The Merchant of Venice without addressing the status of Jews in Shakespeare’s era, in discussion or supporting materials. Exploring how or why we might see these works today, why they may hold value even when they contain retrograde views, seems essential. It won’t necessarily preempt controversy, but it certainly demonstrates that the people presenting the work understand its complexity and challenges, and that they hope to grapple with those challenges by presenting it in a new light.

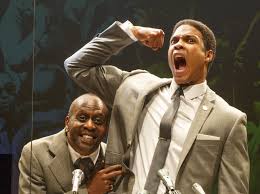

There are also examples of artists addressing work which would now be seen as offensive by placing it within the context of new works and adaptations. Screenings of films featuring Lincoln Perry, better known by the derogatory name Stepin Fetchit, who at one time was the most famous black actor in the movies, would likely be met by scorn if simply programmed without introduction or discussion of the actor and his character at the time he was working. However, playwright Will Power has worked to address Perry’s legacy by making him a leading character in the play Fetch Clay, Make Man, which places him alongside Cassius Clay (as he became Muhammed Ali) as two icons of African-American popular culture. It’s also unlikely that few theatre companies would produces the once hugely popular melodrama The Octoroon, with its far outdated racial views, but Branden Jacobs-Jenkins has deconstructed the work as part of his play An Octoroon, folding the original material directly into commentary on the same piece.

There are many who defend The Mikado by citing Gilbert and Sullivan’s love of Asian culture and their efforts to represent it, but that often accompanies productions with white actors in yellowface; this ongoing controversy arose once again this summer in Seattle. But 28 years ago director Jonathan Miller found a way to present the work by resetting it in a seaside English resort, allowing the characters in what was widely known to be a spoof of the British aristocracy to be seen as exactly that, instead of antiquated racial caricatures. Again, context and interpretation is all.

I take exception to Kennicott’s characterization of “Cultural leaders who fret about art causing discomfort,” since it evidences a lack of comprehension of the role of those leaders. Yes, we should want all artistic ventures to be brave and bold, and to even take audiences places where they might not necessarily think to go. But they must do so in the context of serving their community, and indeed their many communities, because they do not and cannot exist in a vacuum where art cannot be challenged, often vigorously, in critiques and discussion simply because it has been declared art.

In every generation, art is a dialogue between artists and audiences, whether in performance or fixed texts and images; just as some works aren’t recognized or accepted when first created, there are also those which cease to hold meaning or whose meaning changes as society advances. If an artistic leader chooses to produce a season of vintage works with passé portrayals of women, people of color, people with disabilities, sexual orientation and so on as they might have first been seen, that is absolutely their right. But it is also the right of those who know the work or see it to challenge those decisions – though I abhor the kinds of threats that have emerged over Klinghoffer or Exhibit B at the Barbican, even as I support the rights of the voices which oppose those works to express their opinions. It is very easy in theory to say all works should remain fixed, but reality is another matter altogether.

There are no absolutes in this discussion. If works out of copyright are altered for this production or that, the work itself remains fixed for yet another day, and each example can be judged in relation to the original text. Inevitably, for every leader, whether teacher or producer, it is a matter of balancing a wide range of opinions and perceptions. I personally believe in art for art’s sake alongside art for audiences’ sake, but art for history’s sake serves only the past and runs the risk of propagating the failings of the past. In the arts, history should not be wholly erased, but it should first and foremost be the foundation upon which we build a better future.

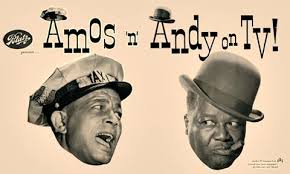

P.S. Among the examples Kennicott cites as falling prey to cultural sanitization is Amos and Andy. While it is true that the show was recognized as an avatar of racial insensitivity when viewed through the enlightened prism of the 1960s civil rights struggle, its absence from the airwaves or cable box is now due just as much to it no longer being commercially viable as to its racial stereotyping. That holds true as well for countless shows from the era, for reasons ranging from a changed society where the work is no longer seen as positive (such as my childhood favorites F Troop and I Dream of Jeannie) to their being in black and white and in the old TV aspect ratio. But Amos and Andy hasn’t been erased: you can view the TV episodes in the collection of the Paley Center for Media or buy the DVDs on Amazon and see for yourself why it’s now for the history books and academic, not mass entertainment.

P.S. Among the examples Kennicott cites as falling prey to cultural sanitization is Amos and Andy. While it is true that the show was recognized as an avatar of racial insensitivity when viewed through the enlightened prism of the 1960s civil rights struggle, its absence from the airwaves or cable box is now due just as much to it no longer being commercially viable as to its racial stereotyping. That holds true as well for countless shows from the era, for reasons ranging from a changed society where the work is no longer seen as positive (such as my childhood favorites F Troop and I Dream of Jeannie) to their being in black and white and in the old TV aspect ratio. But Amos and Andy hasn’t been erased: you can view the TV episodes in the collection of the Paley Center for Media or buy the DVDs on Amazon and see for yourself why it’s now for the history books and academic, not mass entertainment.