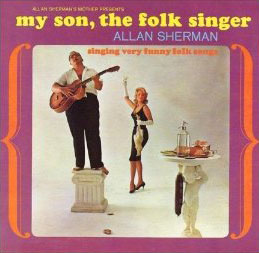

As a teen in the 1970s, I kept testing a small sociological phenomenon. When visiting a Jewish home, I would peek at the record collection of the adults in residence to see if they had the album “My Son, The Folk Singer.” If the family was Catholic or Protestant, I’d look for “The First Family” featuring Vaughn Meader. To my recollection, I never failed to find the anticipated album in the expected home, even though both records were already at least a decade old before I began my study. While this did not foretell a future career as a social anthropologist, it always gave me a little hit of satisfaction, as if I’d tumbled to some unique cultural signifier.

As a teen in the 1970s, I kept testing a small sociological phenomenon. When visiting a Jewish home, I would peek at the record collection of the adults in residence to see if they had the album “My Son, The Folk Singer.” If the family was Catholic or Protestant, I’d look for “The First Family” featuring Vaughn Meader. To my recollection, I never failed to find the anticipated album in the expected home, even though both records were already at least a decade old before I began my study. While this did not foretell a future career as a social anthropologist, it always gave me a little hit of satisfaction, as if I’d tumbled to some unique cultural signifier.

“The First Family” was a 1962 comedy album that satirized the Kennedy clan very lightly and it briefly made a star of Meader. Of course, his career as a JFK impersonator was cut short in November 1963, but for one year, his fame was such that reportedly when Lenny Bruce performed for the first time after the president’s assassination, his first words were reportedly some variant of, “Wow, Vaughn Meader’s screwed.”

“My Son, The Folk Singer” was written and performed by a previously all but unknown TV writer and producer named Allan Sherman, who was in his late 30s when the recording debuted in 1962. It was such a phenomenon that it set sales records not simply for comedy records but for the recording industry in general, and demand for Sherman’s Yiddish inflected and overwhelmingly Jewish parodies of folk and later popular songs was such that he released his first three albums (out of eight in his whole career) within a single 12-month period. For a few years he was a huge name – touring night clubs and concert venues, guest hosting for Johnny Carson, appearing in his own TV specials – but he turned out to be a fad, especially as radio formats changed, marginalizing novelty records. When he died of a heart attack in 1973 at the age of 49, his career has already been all but over for several years. I discovered Sherman at roughly the same time, unaware of his passing — I can still sing any number of his parodies at the drop of a hat.

The new biography, Overweight Sensation: The Life and Comedy of Allan Sherman by Mark Cohen (Brandeis University Press, $29.95) is a comprehensive look at the career of the man best remembered today, if at all (outside of older Jews and comedy buffs), for his tale of a summer camp sojourn gone awry, “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah.” As might be expected of a book that is part of the publishing house’s “Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life,” Sensation views Sherman through a Semitic lens, arguing for his role in popular acceptance of Jews in American culture. While Jewish comedians (and writers, performers, and so on) had flourished for decades, Cohen posits that Sherman’s success was a key crossover point that freed Jewish artists to speak openly of their race, and indeed Jewish identity was central to Sherman’s earliest work. That he was welcomed at The White House is touted as a symbol of Sherman’s cross-cultural barrier breaking, as is his popular success throughout the country.

The new biography, Overweight Sensation: The Life and Comedy of Allan Sherman by Mark Cohen (Brandeis University Press, $29.95) is a comprehensive look at the career of the man best remembered today, if at all (outside of older Jews and comedy buffs), for his tale of a summer camp sojourn gone awry, “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah.” As might be expected of a book that is part of the publishing house’s “Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life,” Sensation views Sherman through a Semitic lens, arguing for his role in popular acceptance of Jews in American culture. While Jewish comedians (and writers, performers, and so on) had flourished for decades, Cohen posits that Sherman’s success was a key crossover point that freed Jewish artists to speak openly of their race, and indeed Jewish identity was central to Sherman’s earliest work. That he was welcomed at The White House is touted as a symbol of Sherman’s cross-cultural barrier breaking, as is his popular success throughout the country.

Because of its concentration on this thesis, the book seems to give somewhat short shrift to other Jews breaking into popular consciousness and in some cases into the mainstream at about the same time; the fertile environment for recorded comedy, at its height in the early 60s, is likewise diminished. Stan Freberg (The History of The United States of America) and Tom Lehrer (“Poisoning Pigeons in the Park“) merit nary a mention (despite writing both words and music to their melodic satires before Sherman came on the scene; the latter Jewish, the former not); non-singing Jewish comics like Shelley Berman and Brooks & Reiner (The 2,000 Year Old Man) are given little attention. That’s not to say Sherman wasn’t important, but he didn’t exist in a vacuum. He burned brighter for a short time, and had a verbal dexterity admired even by Richard Rodgers, but it’s Lehrer and Freberg’s work that is often cited for its brilliance by comedians and composers a half-century later. Reiner, Brooks and Woody Allen (“The Moose“) may have started slower, but were surely more influential Jewish voices in the long run.

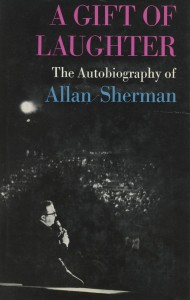

Sherman’s story plays out like the script of a thorough, culturally oriented “Behind The Music” episode, with a bit of Jewish motherdom thrown in for good measure. Cohen breaks down the comedian’s life as: he came from a terrible, broken family (such a shondeh) as a result of which he never grew up; he was a parodic genius (we’re kvelling); and already predisposed to poor health by his weight, he was done in by the trappings of success even as it left him (he’s always shicker, and cavorting with shiksas). There’s more than a hint of posthumous guilt being levied on Sherman for his various appetites (both gustatory and carnal) and shortcomings, while the enthusiasm for his culturally specific parodic work is unstinting. But the book’s research and complete lifetime overview makes it a vastly better reference document than Sherman’s autobiography, A Gift of Laughter, published in 1965 just as his career began to wane – and, according to Sensation, largely ghost-written and intermittently dishonest.

Sherman’s story plays out like the script of a thorough, culturally oriented “Behind The Music” episode, with a bit of Jewish motherdom thrown in for good measure. Cohen breaks down the comedian’s life as: he came from a terrible, broken family (such a shondeh) as a result of which he never grew up; he was a parodic genius (we’re kvelling); and already predisposed to poor health by his weight, he was done in by the trappings of success even as it left him (he’s always shicker, and cavorting with shiksas). There’s more than a hint of posthumous guilt being levied on Sherman for his various appetites (both gustatory and carnal) and shortcomings, while the enthusiasm for his culturally specific parodic work is unstinting. But the book’s research and complete lifetime overview makes it a vastly better reference document than Sherman’s autobiography, A Gift of Laughter, published in 1965 just as his career began to wane – and, according to Sensation, largely ghost-written and intermittently dishonest.

Coming from an academic press into a world that has largely forgotten him, Overweight Sensation is unlikely to spark a Sherman renaissance, but it does thoroughly memorialize the career of a man whose comedy prefigured that of other singing parodists, notably Al Yankovic, with whom he shared on obsessions with songs about food and weight (i.e. Sherman’s “Grow Mrs. Goldfarb” and “Hail To Thee, Fat Person“; Weird Al’s “Fat” and “Eat It“). It also has the bonus of an appendix featuring lyrics Sherman wrote and never released commercially; based on familiar songs, readers can easily sing them for themselves. And if he was not the sole trailblazer for Jewish life and language assimilating into mainstream culture, he certainly played a key role that is deserving of acknowledgement and remembrance, as do some of his parodies, which can still bring laughs 50 years on.

The advent of mp3s has made Sherman’s work readily accessible again after long periods out of print, and YouTube offers the opportunity to sample his oeuvre, beyond the familiarity of the hazard-filled Camp Granada. For a cursory introduction (or reminder), I recommend both the heavily Jewish inventiveness of “Sarah Jackman,” “Shake Hands With Your Uncle Max,” and “My Zelda” and the more secular jauntiness of “Eight Foot Two Solid Blue,” “You Went The Wrong Way Old King Louie,” and (with Sherman on video) “Skin” and “The Painless Dentist Song.”

P.S. No relation.