May 22nd, 2013 § § permalink

My parents were not theatergoers and my youthful memories are not filled with reveries of family trips to New York to see shows. I can remember being taken to the theatre only twice as a youth by my parents, once in 1969 in New Haven (Fiddler on the Roof, national tour) and once in about 1975 on Broadway (The Magic Show). Yet there was something embedded in my DNA which made me interested in performance; I was writing plays (almost all adaptations of existing works) in elementary school with very little frame of reference and undoubtedly even less skill.

My parents were not theatergoers and my youthful memories are not filled with reveries of family trips to New York to see shows. I can remember being taken to the theatre only twice as a youth by my parents, once in 1969 in New Haven (Fiddler on the Roof, national tour) and once in about 1975 on Broadway (The Magic Show). Yet there was something embedded in my DNA which made me interested in performance; I was writing plays (almost all adaptations of existing works) in elementary school with very little frame of reference and undoubtedly even less skill.

I longed to be an actor, and vividly remember my envy of Danny Bonaduce on The Partridge Family, thinking if he could be on TV, so could I. This was a bit odd, because I was a rather socially awkward child who didn’t mix well with most kids in my elementary years; I read constantly and had to be pushed outside into fresh air, where I invariably kept reading. Unlike many drawn to performing, music didn’t have a big role in my childhood, outside of Top 40 AM fare once I had my own little transistor radio. My parents didn’t have a record collection to speak of; I do recall my mother’s beloved two-disc set of Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, and some assorted children’s records, such as the Mary Poppins soundtrack and Danny Kaye’s Mommy, Give Me a Drink Of Water and Tubby the Tuba. Cast recordings, which loom large in the memories of theatre pros, were absent, save for Fiddler on the Roof (culturally imperative, but rarely played) and West Side Story (likewise, but we only listened to “Dear Officer Krupke”).

I longed to be an actor, and vividly remember my envy of Danny Bonaduce on The Partridge Family, thinking if he could be on TV, so could I. This was a bit odd, because I was a rather socially awkward child who didn’t mix well with most kids in my elementary years; I read constantly and had to be pushed outside into fresh air, where I invariably kept reading. Unlike many drawn to performing, music didn’t have a big role in my childhood, outside of Top 40 AM fare once I had my own little transistor radio. My parents didn’t have a record collection to speak of; I do recall my mother’s beloved two-disc set of Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, and some assorted children’s records, such as the Mary Poppins soundtrack and Danny Kaye’s Mommy, Give Me a Drink Of Water and Tubby the Tuba. Cast recordings, which loom large in the memories of theatre pros, were absent, save for Fiddler on the Roof (culturally imperative, but rarely played) and West Side Story (likewise, but we only listened to “Dear Officer Krupke”).

So I’ve often wondered how I managed to be cast in lead roles in each and every show (save one) that I auditioned for in junior high, high school, community theatre and college, and why being on stage or in speaking in front of large groups has never frightened me. I’ve come to understand that part of the appeal, and the ease, came from the stage offering the exact opposite of day to day life. On stage, I always knew what to say and when to say it, and when I did it right, I was rewarded with laughter and applause. It was a startling contrast from the uncertainty of casual interaction. Where did I learn this skill? Comedy records.

So I’ve often wondered how I managed to be cast in lead roles in each and every show (save one) that I auditioned for in junior high, high school, community theatre and college, and why being on stage or in speaking in front of large groups has never frightened me. I’ve come to understand that part of the appeal, and the ease, came from the stage offering the exact opposite of day to day life. On stage, I always knew what to say and when to say it, and when I did it right, I was rewarded with laughter and applause. It was a startling contrast from the uncertainty of casual interaction. Where did I learn this skill? Comedy records.

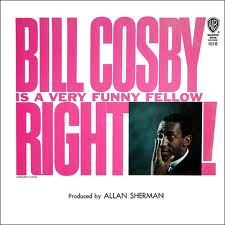

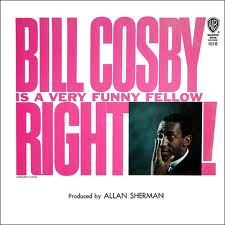

As a tween and teen in the early 70s, in the pre home video era, I was completely entranced by comedy recordings both current and from the relatively recent past. My brother and I came together primarily over our basement record player and the comedy collection scavenged from yard sales (and Monty Python on PBS). We had a bunch of the earliest Bill Cosby albums, the deeply politically incorrect Jose Jimenez In Orbit, a Smothers Brothers disc and (purchased new, smuggled in) George Carlin’s AM/FM and Class Clown. These are the ones that come to mind; there may have been more.

As a tween and teen in the early 70s, in the pre home video era, I was completely entranced by comedy recordings both current and from the relatively recent past. My brother and I came together primarily over our basement record player and the comedy collection scavenged from yard sales (and Monty Python on PBS). We had a bunch of the earliest Bill Cosby albums, the deeply politically incorrect Jose Jimenez In Orbit, a Smothers Brothers disc and (purchased new, smuggled in) George Carlin’s AM/FM and Class Clown. These are the ones that come to mind; there may have been more.

We listened to these albums over and over as if they were music, and reached the point where we knew entire routines by heart. Not just the words, but the pacing, the inflections, the comics impersonations of other characters and performers. Each routine was a song, and we would recite along with the records. We worked to perfect Carlin’s Spike Jones “hiccup” before we’d ever heard a Spike Jones record. We were mesmerized by them, long after the surprise of the jokes had faded; of course, the contraband Carlin album made us very adventuresome among our peers because of its “dirty” language (we were perhaps 12 or 13 at the time).

We listened to these albums over and over as if they were music, and reached the point where we knew entire routines by heart. Not just the words, but the pacing, the inflections, the comics impersonations of other characters and performers. Each routine was a song, and we would recite along with the records. We worked to perfect Carlin’s Spike Jones “hiccup” before we’d ever heard a Spike Jones record. We were mesmerized by them, long after the surprise of the jokes had faded; of course, the contraband Carlin album made us very adventuresome among our peers because of its “dirty” language (we were perhaps 12 or 13 at the time).

I never of thought about these records as scripts, but they were almost sacred texts to us. If we learn to perform first by imitating and later by finding our own style, then we were taking a suburban master class from performers at places like The hungry i in San Francisco before we’d ever been on an airplane and before we would have been old enough to gain admittance even had we managed the trek. The lessons ran deep: a couple of years ago, a gift set of Carlin CDs accompanied me on a road trip, and my wife was both amused and annoyed by my ability to recall every moment with precision, despite my not having heard the material in many years. Did I ever find a style of my own, moving beyond mimicry? That’s for others to say.

My actual performing years were brief, covering 1977 to 1981, 10 shows in all. I was perhaps the fussiest Oscar Madison in history, since most see me as a Felix; I probably shouted more than any one of the 12 Angry Men as Juror 3; I managed to make the characters of Will Parker and Albert Peterson the most inept dancers in their history. I suspect I was best in roles that called for comedy over movement or voice: the Woody Allen stand-in Axel Magee in Don’t Drink The Water, the meek Motel Kamzoil in Fiddler, and the dirty old man Senex in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum (my college’s newspaper noted a distinct Jewish paternalism in my performance at age 19). Whatever I had, I owed not to the performers from the Golden Age of Theatre, who I would only come to know later, but to the stand-up comedians who were the writers and performers I took close to heart – if for no other reasons than that they were repeatedly accessible on the technology that was available to me.

My actual performing years were brief, covering 1977 to 1981, 10 shows in all. I was perhaps the fussiest Oscar Madison in history, since most see me as a Felix; I probably shouted more than any one of the 12 Angry Men as Juror 3; I managed to make the characters of Will Parker and Albert Peterson the most inept dancers in their history. I suspect I was best in roles that called for comedy over movement or voice: the Woody Allen stand-in Axel Magee in Don’t Drink The Water, the meek Motel Kamzoil in Fiddler, and the dirty old man Senex in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum (my college’s newspaper noted a distinct Jewish paternalism in my performance at age 19). Whatever I had, I owed not to the performers from the Golden Age of Theatre, who I would only come to know later, but to the stand-up comedians who were the writers and performers I took close to heart – if for no other reasons than that they were repeatedly accessible on the technology that was available to me.

I do not suggest that aspiring performers should run out and start learning comedy albums by heart, though one could do worse for understanding timing and pace. Of course, now we can watch and not merely listen to comedians and work out their full routines step by step; I wonder whether the visuals would have added to our mimicry or distracted us from the deep concentration on words and delivery that took place as a ritual in our cluttered basement, our nightclub of the mind. But I am sure of one thing: there are many ways to find one’s way to the stage, and mine was through the storytelling and punchlines of some modern masters of the comedy genre.

I do not suggest that aspiring performers should run out and start learning comedy albums by heart, though one could do worse for understanding timing and pace. Of course, now we can watch and not merely listen to comedians and work out their full routines step by step; I wonder whether the visuals would have added to our mimicry or distracted us from the deep concentration on words and delivery that took place as a ritual in our cluttered basement, our nightclub of the mind. But I am sure of one thing: there are many ways to find one’s way to the stage, and mine was through the storytelling and punchlines of some modern masters of the comedy genre.

P.S. My vocal coaches were Tom Lehrer, Stan Freberg, and Allan Sherman. But that’s another story.

May 20th, 2013 § § permalink

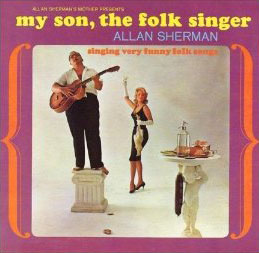

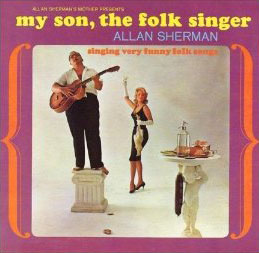

As a teen in the 1970s, I kept testing a small sociological phenomenon. When visiting a Jewish home, I would peek at the record collection of the adults in residence to see if they had the album “My Son, The Folk Singer.” If the family was Catholic or Protestant, I’d look for “The First Family” featuring Vaughn Meader. To my recollection, I never failed to find the anticipated album in the expected home, even though both records were already at least a decade old before I began my study. While this did not foretell a future career as a social anthropologist, it always gave me a little hit of satisfaction, as if I’d tumbled to some unique cultural signifier.

As a teen in the 1970s, I kept testing a small sociological phenomenon. When visiting a Jewish home, I would peek at the record collection of the adults in residence to see if they had the album “My Son, The Folk Singer.” If the family was Catholic or Protestant, I’d look for “The First Family” featuring Vaughn Meader. To my recollection, I never failed to find the anticipated album in the expected home, even though both records were already at least a decade old before I began my study. While this did not foretell a future career as a social anthropologist, it always gave me a little hit of satisfaction, as if I’d tumbled to some unique cultural signifier.

“The First Family” was a 1962 comedy album that satirized the Kennedy clan very lightly and it briefly made a star of Meader. Of course, his career as a JFK impersonator was cut short in November 1963, but for one year, his fame was such that reportedly when Lenny Bruce performed for the first time after the president’s assassination, his first words were reportedly some variant of, “Wow, Vaughn Meader’s screwed.”

“My Son, The Folk Singer” was written and performed by a previously all but unknown TV writer and producer named Allan Sherman, who was in his late 30s when the recording debuted in 1962. It was such a phenomenon that it set sales records not simply for comedy records but for the recording industry in general, and demand for Sherman’s Yiddish inflected and overwhelmingly Jewish parodies of folk and later popular songs was such that he released his first three albums (out of eight in his whole career) within a single 12-month period. For a few years he was a huge name – touring night clubs and concert venues, guest hosting for Johnny Carson, appearing in his own TV specials – but he turned out to be a fad, especially as radio formats changed, marginalizing novelty records. When he died of a heart attack in 1973 at the age of 49, his career has already been all but over for several years. I discovered Sherman at roughly the same time, unaware of his passing — I can still sing any number of his parodies at the drop of a hat.

The new biography, Overweight Sensation: The Life and Comedy of Allan Sherman by Mark Cohen (Brandeis University Press, $29.95) is a comprehensive look at the career of the man best remembered today, if at all (outside of older Jews and comedy buffs), for his tale of a summer camp sojourn gone awry, “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah.” As might be expected of a book that is part of the publishing house’s “Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life,” Sensation views Sherman through a Semitic lens, arguing for his role in popular acceptance of Jews in American culture. While Jewish comedians (and writers, performers, and so on) had flourished for decades, Cohen posits that Sherman’s success was a key crossover point that freed Jewish artists to speak openly of their race, and indeed Jewish identity was central to Sherman’s earliest work. That he was welcomed at The White House is touted as a symbol of Sherman’s cross-cultural barrier breaking, as is his popular success throughout the country.

The new biography, Overweight Sensation: The Life and Comedy of Allan Sherman by Mark Cohen (Brandeis University Press, $29.95) is a comprehensive look at the career of the man best remembered today, if at all (outside of older Jews and comedy buffs), for his tale of a summer camp sojourn gone awry, “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah.” As might be expected of a book that is part of the publishing house’s “Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life,” Sensation views Sherman through a Semitic lens, arguing for his role in popular acceptance of Jews in American culture. While Jewish comedians (and writers, performers, and so on) had flourished for decades, Cohen posits that Sherman’s success was a key crossover point that freed Jewish artists to speak openly of their race, and indeed Jewish identity was central to Sherman’s earliest work. That he was welcomed at The White House is touted as a symbol of Sherman’s cross-cultural barrier breaking, as is his popular success throughout the country.

Because of its concentration on this thesis, the book seems to give somewhat short shrift to other Jews breaking into popular consciousness and in some cases into the mainstream at about the same time; the fertile environment for recorded comedy, at its height in the early 60s, is likewise diminished. Stan Freberg (The History of The United States of America) and Tom Lehrer (“Poisoning Pigeons in the Park“) merit nary a mention (despite writing both words and music to their melodic satires before Sherman came on the scene; the latter Jewish, the former not); non-singing Jewish comics like Shelley Berman and Brooks & Reiner (The 2,000 Year Old Man) are given little attention. That’s not to say Sherman wasn’t important, but he didn’t exist in a vacuum. He burned brighter for a short time, and had a verbal dexterity admired even by Richard Rodgers, but it’s Lehrer and Freberg’s work that is often cited for its brilliance by comedians and composers a half-century later. Reiner, Brooks and Woody Allen (“The Moose“) may have started slower, but were surely more influential Jewish voices in the long run.

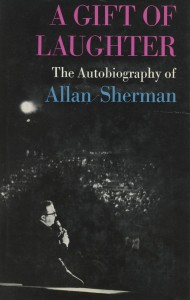

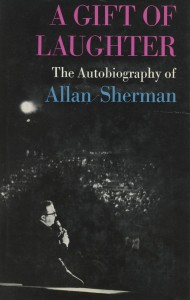

Sherman’s story plays out like the script of a thorough, culturally oriented “Behind The Music” episode, with a bit of Jewish motherdom thrown in for good measure. Cohen breaks down the comedian’s life as: he came from a terrible, broken family (such a shondeh) as a result of which he never grew up; he was a parodic genius (we’re kvelling); and already predisposed to poor health by his weight, he was done in by the trappings of success even as it left him (he’s always shicker, and cavorting with shiksas). There’s more than a hint of posthumous guilt being levied on Sherman for his various appetites (both gustatory and carnal) and shortcomings, while the enthusiasm for his culturally specific parodic work is unstinting. But the book’s research and complete lifetime overview makes it a vastly better reference document than Sherman’s autobiography, A Gift of Laughter, published in 1965 just as his career began to wane – and, according to Sensation, largely ghost-written and intermittently dishonest.

Sherman’s story plays out like the script of a thorough, culturally oriented “Behind The Music” episode, with a bit of Jewish motherdom thrown in for good measure. Cohen breaks down the comedian’s life as: he came from a terrible, broken family (such a shondeh) as a result of which he never grew up; he was a parodic genius (we’re kvelling); and already predisposed to poor health by his weight, he was done in by the trappings of success even as it left him (he’s always shicker, and cavorting with shiksas). There’s more than a hint of posthumous guilt being levied on Sherman for his various appetites (both gustatory and carnal) and shortcomings, while the enthusiasm for his culturally specific parodic work is unstinting. But the book’s research and complete lifetime overview makes it a vastly better reference document than Sherman’s autobiography, A Gift of Laughter, published in 1965 just as his career began to wane – and, according to Sensation, largely ghost-written and intermittently dishonest.

Coming from an academic press into a world that has largely forgotten him, Overweight Sensation is unlikely to spark a Sherman renaissance, but it does thoroughly memorialize the career of a man whose comedy prefigured that of other singing parodists, notably Al Yankovic, with whom he shared on obsessions with songs about food and weight (i.e. Sherman’s “Grow Mrs. Goldfarb” and “Hail To Thee, Fat Person“; Weird Al’s “Fat” and “Eat It“). It also has the bonus of an appendix featuring lyrics Sherman wrote and never released commercially; based on familiar songs, readers can easily sing them for themselves. And if he was not the sole trailblazer for Jewish life and language assimilating into mainstream culture, he certainly played a key role that is deserving of acknowledgement and remembrance, as do some of his parodies, which can still bring laughs 50 years on.

The advent of mp3s has made Sherman’s work readily accessible again after long periods out of print, and YouTube offers the opportunity to sample his oeuvre, beyond the familiarity of the hazard-filled Camp Granada. For a cursory introduction (or reminder), I recommend both the heavily Jewish inventiveness of “Sarah Jackman,” “Shake Hands With Your Uncle Max,” and “My Zelda” and the more secular jauntiness of “Eight Foot Two Solid Blue,” “You Went The Wrong Way Old King Louie,” and (with Sherman on video) “Skin” and “The Painless Dentist Song.”

P.S. No relation.

April 30th, 2013 § § permalink

Though I’ve occasionally written about topics outside of theatre and the performing arts, with this post I’ll be titling them as a distinct series, affording me the opportunity to stray wider in my writing while noting when I’m “off-topic.” So here’s the first “Etcetera.”

If I tell you that I fondly recall coming home from junior high in the mid-1970s and huddling up to my radio for the verbal entertainment found there, I hope you will be struck by the incongruity of the date and the medium of choice. There was a burst of nostalgia for radio comedy and drama in that era; one station that I could receive, if the weather conditions were right, scheduled classic shows like Fibber McGee and Molly and The Shadow weekly; radio veteran Himan Brown launched a new series of radio plays called the CBS Radio Mystery Theatre (archived here), and even the countercultural satirists at the National Lampoon syndicated their Radio Hour, a precursor to their own stage show Lemmings and shortly thereafter, the debut of Saturday Night Live.

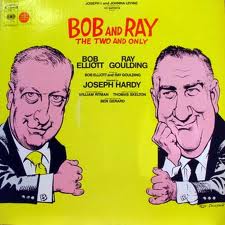

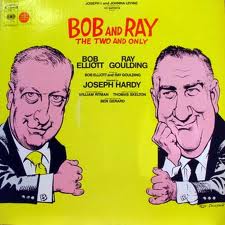

I loved them all, but the most intriguing were the evening drive-time broadcasters on New York’s WOR, Bob and Ray. They would chat, do segues to traffic and news reports and intermittently launch into decidedly off-kilter comic sequences. Those I remember best were the serialized “Mary Backstayge, Noble Wife” and “Garish Summit.” None of my friends at the time listened to this stuff and it wasn’t until I got to college that I discovered the cult of Bob and Ray, who, as it turned out, were in their final regular radio run as I listened, having started their careers in the late 40s.

I loved them all, but the most intriguing were the evening drive-time broadcasters on New York’s WOR, Bob and Ray. They would chat, do segues to traffic and news reports and intermittently launch into decidedly off-kilter comic sequences. Those I remember best were the serialized “Mary Backstayge, Noble Wife” and “Garish Summit.” None of my friends at the time listened to this stuff and it wasn’t until I got to college that I discovered the cult of Bob and Ray, who, as it turned out, were in their final regular radio run as I listened, having started their careers in the late 40s.

In the just-published Bob and Ray: Keener Than Most Person (Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, $27.99), David Pollack provides the first biography of the duo, from their fortuitous pairing in 1946 through Ray’s death in 1990. Though their material has circulated for years, on tape and records (later CDs), in books and now on YouTube, the book offers the opportunity to learn the detail (even minutiae) of their joint career, including their early leap from radio to television in the latter’s earliest days, their role (along with another hero of mine, Stan Freberg) at injecting humor into advertising, and their reluctant foray onto the Broadway stage in 1970.

The book goes out of its way to point out what ordinary guys Bob (Elliott) and Ray (Goulding) were and how much they eschewed the trappings of even minor celebrity. It also repeatedly comments on the lack of conflict between the two, only mentioning Ray’s occasional flashes of anger that were quickly forgotten. There’s no tell-all here, pretty much just the facts, ma’am, and very little drama.

In addition to noting just how much the duo were outside the comedy mainstream (indeed, they didn’t consider themselves comedians at all), Pollack makes one important observation about the pair’s popularity. Because they performed almost exclusively for years in studios – not stages or nightclubs – there were no aural cues as to what was funny and what was not. Their humor thrived on being underplayed, and undersold. But what may have made them truly unique was that without a live audience, fans would feel they were an audience of one, communing directly with the hosts from their car or home, unmediated and deeply personal.

In addition to noting just how much the duo were outside the comedy mainstream (indeed, they didn’t consider themselves comedians at all), Pollack makes one important observation about the pair’s popularity. Because they performed almost exclusively for years in studios – not stages or nightclubs – there were no aural cues as to what was funny and what was not. Their humor thrived on being underplayed, and undersold. But what may have made them truly unique was that without a live audience, fans would feel they were an audience of one, communing directly with the hosts from their car or home, unmediated and deeply personal.

Save for the occasional line of dialogue, Bob and Ray, Keener Than Most Persons reproduces none of the duo’s material and its straightforward, authorized telling makes the assumption that you’re reading the book because you’re already a fan; there’s no effort to drum up new aficionados. While such an effort would have been challenging given that so much of Bob and Ray’s humor emanates from their rapport and timing, it’s hardly impossible to proselytize for comedians of the past; witness Dick Cavett’s superb evocation of the once sui generis improv of Jonathan Winters, which just ran in The New York Times.

So I must urge you to head to YouTube, to listen to my indescribable favorites, “The Komodo Dragon Expert” and “The Slow Talker,” both from their Broadway stand (therefore, with atypical audience laughter). Then just keep searching.

A personal addendum, less than 24 hours old. When the book arrived and landed on my coffee table, my wife’s response was, “Bob and Ray. Who are they?” At the time I didn’t launch into a rhapsody, but last night, having just read the book on an airplane, I began talking about Bob Elliott and Ray Goulding, mentioning that I thought Ray might have lived near her family on Long Island. “Goulding?” she said. “I went to school with a Mark Goulding. His dad did something in radio.” I showed her pictures from the book and, indeed, my wife recognized Ray Goulding from school events. He flew under the radar even in his own town.

I, of course, was floored to find that my wife had come so close to one of my heroes, completely unaware. So I played the two pieces mentioned above, and we both laughed until tears came to our eyes. I am happy to report that nearly 70 years after they began working together, I had just recruited a new fan to the cult of Bob and Ray. Join us, won’t you?

My parents were not theatergoers and my youthful memories are not filled with reveries of family trips to New York to see shows. I can remember being taken to the theatre only twice as a youth by my parents, once in 1969 in New Haven (Fiddler on the Roof, national tour) and once in about 1975 on Broadway (The Magic Show). Yet there was something embedded in my DNA which made me interested in performance; I was writing plays (almost all adaptations of existing works) in elementary school with very little frame of reference and undoubtedly even less skill.

My parents were not theatergoers and my youthful memories are not filled with reveries of family trips to New York to see shows. I can remember being taken to the theatre only twice as a youth by my parents, once in 1969 in New Haven (Fiddler on the Roof, national tour) and once in about 1975 on Broadway (The Magic Show). Yet there was something embedded in my DNA which made me interested in performance; I was writing plays (almost all adaptations of existing works) in elementary school with very little frame of reference and undoubtedly even less skill. I longed to be an actor, and vividly remember my envy of Danny Bonaduce on The Partridge Family, thinking if he could be on TV, so could I. This was a bit odd, because I was a rather socially awkward child who didn’t mix well with most kids in my elementary years; I read constantly and had to be pushed outside into fresh air, where I invariably kept reading. Unlike many drawn to performing, music didn’t have a big role in my childhood, outside of Top 40 AM fare once I had my own little transistor radio. My parents didn’t have a record collection to speak of; I do recall my mother’s beloved two-disc set of Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, and some assorted children’s records, such as the Mary Poppins soundtrack and Danny Kaye’s Mommy, Give Me a Drink Of Water and Tubby the Tuba. Cast recordings, which loom large in the memories of theatre pros, were absent, save for Fiddler on the Roof (culturally imperative, but rarely played) and West Side Story (likewise, but we only listened to “Dear Officer Krupke”).

I longed to be an actor, and vividly remember my envy of Danny Bonaduce on The Partridge Family, thinking if he could be on TV, so could I. This was a bit odd, because I was a rather socially awkward child who didn’t mix well with most kids in my elementary years; I read constantly and had to be pushed outside into fresh air, where I invariably kept reading. Unlike many drawn to performing, music didn’t have a big role in my childhood, outside of Top 40 AM fare once I had my own little transistor radio. My parents didn’t have a record collection to speak of; I do recall my mother’s beloved two-disc set of Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, and some assorted children’s records, such as the Mary Poppins soundtrack and Danny Kaye’s Mommy, Give Me a Drink Of Water and Tubby the Tuba. Cast recordings, which loom large in the memories of theatre pros, were absent, save for Fiddler on the Roof (culturally imperative, but rarely played) and West Side Story (likewise, but we only listened to “Dear Officer Krupke”). So I’ve often wondered how I managed to be cast in lead roles in each and every show (save one) that I auditioned for in junior high, high school, community theatre and college, and why being on stage or in speaking in front of large groups has never frightened me. I’ve come to understand that part of the appeal, and the ease, came from the stage offering the exact opposite of day to day life. On stage, I always knew what to say and when to say it, and when I did it right, I was rewarded with laughter and applause. It was a startling contrast from the uncertainty of casual interaction. Where did I learn this skill? Comedy records.

So I’ve often wondered how I managed to be cast in lead roles in each and every show (save one) that I auditioned for in junior high, high school, community theatre and college, and why being on stage or in speaking in front of large groups has never frightened me. I’ve come to understand that part of the appeal, and the ease, came from the stage offering the exact opposite of day to day life. On stage, I always knew what to say and when to say it, and when I did it right, I was rewarded with laughter and applause. It was a startling contrast from the uncertainty of casual interaction. Where did I learn this skill? Comedy records. As a tween and teen in the early 70s, in the pre home video era, I was completely entranced by comedy recordings both current and from the relatively recent past. My brother and I came together primarily over our basement record player and the comedy collection scavenged from yard sales (and Monty Python on PBS). We had a bunch of the earliest Bill Cosby albums, the deeply politically incorrect Jose Jimenez In Orbit, a Smothers Brothers disc and (purchased new, smuggled in) George Carlin’s AM/FM and Class Clown. These are the ones that come to mind; there may have been more.

As a tween and teen in the early 70s, in the pre home video era, I was completely entranced by comedy recordings both current and from the relatively recent past. My brother and I came together primarily over our basement record player and the comedy collection scavenged from yard sales (and Monty Python on PBS). We had a bunch of the earliest Bill Cosby albums, the deeply politically incorrect Jose Jimenez In Orbit, a Smothers Brothers disc and (purchased new, smuggled in) George Carlin’s AM/FM and Class Clown. These are the ones that come to mind; there may have been more. We listened to these albums over and over as if they were music, and reached the point where we knew entire routines by heart. Not just the words, but the pacing, the inflections, the comics impersonations of other characters and performers. Each routine was a song, and we would recite along with the records. We worked to perfect Carlin’s Spike Jones “hiccup” before we’d ever heard a Spike Jones record. We were mesmerized by them, long after the surprise of the jokes had faded; of course, the contraband Carlin album made us very adventuresome among our peers because of its “dirty” language (we were perhaps 12 or 13 at the time).

We listened to these albums over and over as if they were music, and reached the point where we knew entire routines by heart. Not just the words, but the pacing, the inflections, the comics impersonations of other characters and performers. Each routine was a song, and we would recite along with the records. We worked to perfect Carlin’s Spike Jones “hiccup” before we’d ever heard a Spike Jones record. We were mesmerized by them, long after the surprise of the jokes had faded; of course, the contraband Carlin album made us very adventuresome among our peers because of its “dirty” language (we were perhaps 12 or 13 at the time). My actual performing years were brief, covering 1977 to 1981, 10 shows in all. I was perhaps the fussiest Oscar Madison in history, since most see me as a Felix; I probably shouted more than any one of the 12 Angry Men as Juror 3; I managed to make the characters of Will Parker and Albert Peterson the most inept dancers in their history. I suspect I was best in roles that called for comedy over movement or voice: the Woody Allen stand-in Axel Magee in Don’t Drink The Water, the meek Motel Kamzoil in Fiddler, and the dirty old man Senex in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum (my college’s newspaper noted a distinct Jewish paternalism in my performance at age 19). Whatever I had, I owed not to the performers from the Golden Age of Theatre, who I would only come to know later, but to the stand-up comedians who were the writers and performers I took close to heart – if for no other reasons than that they were repeatedly accessible on the technology that was available to me.

My actual performing years were brief, covering 1977 to 1981, 10 shows in all. I was perhaps the fussiest Oscar Madison in history, since most see me as a Felix; I probably shouted more than any one of the 12 Angry Men as Juror 3; I managed to make the characters of Will Parker and Albert Peterson the most inept dancers in their history. I suspect I was best in roles that called for comedy over movement or voice: the Woody Allen stand-in Axel Magee in Don’t Drink The Water, the meek Motel Kamzoil in Fiddler, and the dirty old man Senex in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum (my college’s newspaper noted a distinct Jewish paternalism in my performance at age 19). Whatever I had, I owed not to the performers from the Golden Age of Theatre, who I would only come to know later, but to the stand-up comedians who were the writers and performers I took close to heart – if for no other reasons than that they were repeatedly accessible on the technology that was available to me. I do not suggest that aspiring performers should run out and start learning comedy albums by heart, though one could do worse for understanding timing and pace. Of course, now we can watch and not merely listen to comedians and work out their full routines step by step; I wonder whether the visuals would have added to our mimicry or distracted us from the deep concentration on words and delivery that took place as a ritual in our cluttered basement, our nightclub of the mind. But I am sure of one thing: there are many ways to find one’s way to the stage, and mine was through the storytelling and punchlines of some modern masters of the comedy genre.

I do not suggest that aspiring performers should run out and start learning comedy albums by heart, though one could do worse for understanding timing and pace. Of course, now we can watch and not merely listen to comedians and work out their full routines step by step; I wonder whether the visuals would have added to our mimicry or distracted us from the deep concentration on words and delivery that took place as a ritual in our cluttered basement, our nightclub of the mind. But I am sure of one thing: there are many ways to find one’s way to the stage, and mine was through the storytelling and punchlines of some modern masters of the comedy genre.