Game of Thrones: The Rock Musical – The Unauthorized Parody

Earlier today, I received an invitation to an Off-Broadway show called Game of Thrones: The Rock Musical – The Unauthorized Parody. While I appreciate the offer, I’m not putting the show on my theatre calendar.

The simple reason for this is that I’ve never seen Game of Thrones. So spending time with a spoof of something I know only from a deluge of comments on social media seems unappealing. Yet it’s only the latest in a line of shows which exploit similar territory, creating a theatrical sub-genre: a veritable unauthorized parody parade.

I can think of a few predecessors, including Thank You for Being A Friend (a musical Golden Girls spoof), Showgirls! The Musical!, Friends the Musical Parody, and Bayside! The Saved By The Bell Musical. I’m sure there are more.

I’ve never seen or read the source material to any of these (apart from Friends, which long ago lost its appeal), so I’ve not checked out the shows. Why put myself in the position of being the odd man out when all around me people would be having a good time (presumably) and getting all of the references?

I had an experience much like that at an entertainment called Drunk Shakespeare (I don’t consume alcohol) and attended only because a young former colleague was among its producers. But it simply reminded me of high school and college parties where I felt awkward and out of place.

Of course, anyone can do anything they wish to Shakespeare, whose works haven’t been in any way eligible for even a whisper of copyright protection for centuries. In general, though, even for works under copyright in US law, such as Game of Thrones, there’s a carve-out specifically for parodies. The law insures we can make fun of things, which is a pretty terrific protection.

That said, I can’t help wondering whether many of these shows are emerging less from a creative impulse but rather a baldly mercenary one – that the principle of fair use prompts the creation of works that exist mainly to capitalise on the underlying work. It’s entirely legal, but I have to ask whether it’s a case of commerce over creativity.

I love parody when done well. My friends at the Reduced Shakespeare Company have decades of experience spoofing broad targets – sports, books, US history and the Bible, among others. I thoroughly enjoyed a fringe show called Pulp Shakespeare several years ago, which rendered Tarantino’s film Pulp Fiction in iambic pentameter. I regret missing the one-man show in which the performer enacted Macbeth in the voices of characters from The Simpsons.

Forbidden Broadway has become beloved for taking the theatre itself down a notch, using the tunes of the shows it toys with. But it’s worth noting that its newest incarnation, Spamilton, while taking on more than simply the show its title implies (one of its best jokes comes from a late appearance by a character from a 40-year-old musical), surely benefits from a strong, singular parodic association.

Terry Teachout, drama critic of The Wall Street Journal, has taken to referring to the endless churn of works based on movies that arrive on Broadway as “commodity musicals”.

My bias against some of these spoofs is that I fear they are commodity parodies, judging solely by their marketing. After all, if they must deploy lengthy titles for the specific purpose of ostensibly distancing themselves from their source while simultaneously exploiting it, they’d seem to be trying to have their cake and eat it.

I don’t begrudge the creators of these shows any success nor do I wish to condescend to their audiences. I’m not their target audience as shown by my unfamiliarity with the works they’re sending up.

But even though they may succeed, I suspect that in proliferation, they run the risk of saturating the market, much as movie parodies like Hot Shots and Scary Movie devolved from the heights of Young Frankenstein and Airplane and burned out the genre.

So I forgo certain parodies based on gut instinct, while admittedly delighting in others. For those I skip, perhaps I’ll take the occasional evening off to leaf through my volume of vintage MAD magazine spoofs. After all, even Stephen Sondheim wrote for Off-Broadway’s The Mad Show back in the 1960s. You never know where a parodist could end up someday.

Hannah Cabell and Anna Chlumsky in David Adjmi’s 3C at Rattlestick Playwrights Theater (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Seen any good productions of David Adjmi’s play 3C lately?

Sorry, that’s a trick question with a self-evident answer: of course you haven’t. That’s because in the two and a half years since it premiered at New York’s Rattlestick Playwrights Theater, no one has seen a production of 3C because no one is allowed to produce it, or publish it. Why, you ask? Because a company called DLT Entertainment doesn’t want you to.

3C is an alternate universe look at the 1970s sitcom Three’s Company, one of the prime examples of “jiggle television” from that era, which ran for years based off of the premise that in order to share an apartment with two unmarried women, an unmarried man had to pretend he was gay, to meet with the approval of the landlord. It was a huge hit in its day, and while it was the focus of criticism for its sexual liberality (and constant double entendres), it was viewed as lightweight entertainment with little on its mind but farce and sex (within network constraints), sex that never seemed to actually happen.

Looking at it with today’s eyes, it is a retrograde embarrassment, saved only, perhaps, by the charm and comedy chops of the late John Ritter. The constant jokes about Ritter’s sexual façade, the sexless marriage of the leering landlord and his wife, the macho posturings of the swinging single men, the airheadedness of the women – all have little place in our (hopefully) more enlightened society and the series has pretty much faded from view, save for the occasional resurrection in the wee hours of Nick at Night.

In 3C, Adjmi used the hopelessly out of date sitcom as the template for a despairing look at what life in Apartment 3C might have been had Ritter’s character actually been gay, had the landlord been genuinely predatory and so on. It did what many good parodies do: take a known work and turn it on its ear, making comment not simply on the work itself, but the period and attitudes in which it was first seen.

Enter DLT, which holds the rights to Three’s Company. They sent a cease and desist letter to Adjmi back in 2012 claiming that the show violated their copyright; Adjmi said he couldn’t afford to fight it. Numerous well-known playwrights wrote a letter in support of Adjmi and the controversy generated its first wave of press, including pieces in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Over time, there have been assorted legal filings by both parties, with another wave of press appearing last year just about this time, when Adjmi sued for the right to reclaim his play for production, with commensurate press coverage once again from the Times and Studio 360, among others.

Enter DLT, which holds the rights to Three’s Company. They sent a cease and desist letter to Adjmi back in 2012 claiming that the show violated their copyright; Adjmi said he couldn’t afford to fight it. Numerous well-known playwrights wrote a letter in support of Adjmi and the controversy generated its first wave of press, including pieces in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Over time, there have been assorted legal filings by both parties, with another wave of press appearing last year just about this time, when Adjmi sued for the right to reclaim his play for production, with commensurate press coverage once again from the Times and Studio 360, among others.

Why do I dredge this all up now? Because the bottom line is that DLT is doing its level best to prevent a playwright from earning a living, and throwing everything they can into a specious argument to do so. They say, both in public comments and in their filings, that 3C might confuse audiences and reduce or eliminate the market for their own stage version (citing one they commissioned and one for which they granted permission to James Franco). They cite negative reviews of 3C as damaging to their property. And so on.

But while I’m no lawyer (though I’ve read all of the pertinent briefs on the subject), I can make perfect sense out of the following language from the U.S. Copyright Office, regarding Fair Use exception to copyright (boldface added for emphasis):

The 1961 Report of the Register of Copyrights on the General Revision of the U.S. Copyright Law cites examples of activities that courts have regarded as fair use: “quotation of excerpts in a review or criticism for purposes of illustration or comment; quotation of short passages in a scholarly or technical work, for illustration or clarification of the author’s observations; use in a parody of some of the content of the work parodied; summary of an address or article, with brief quotations, in a news report; reproduction by a library of a portion of a work to replace part of a damaged copy; reproduction by a teacher or student of a small part of a work to illustrate a lesson; reproduction of a work in legislative or judicial proceedings or reports; incidental and fortuitous reproduction, in a newsreel or broadcast, of a work located in the scene of an event being reported.”

As someone who has gone out on a limb at times defending copyright and author’s rights, I’d be the first person to cry foul if I thought DLT had the slightest case here. But 3C (which I’ve read, as it’s part of the legal filings on the case) is so obviously a parody that DLT’s actions seem to be preposterously obstructionist, designed not to protect their property from confusion, but to shield it from the inevitable criticisms that any straightforward presentation of the material would now surely generate.

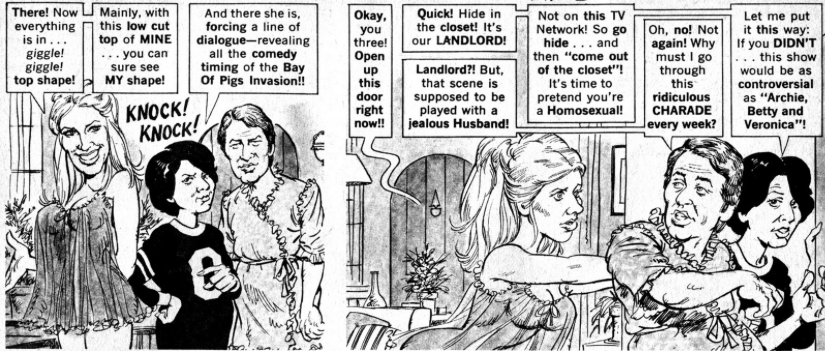

Rather than just blather on about the motivations of DLT in preventing Adjmi from having his play produced and published, let me demonstrate that their argument is specious. To do so, I offer the following exhibit from Mad Magazine:

What’s fascinating here is that Mad, a formative influence for countless youths in the 60s and 70s especially, parodied Three’s Company while it was still on the air, seemed to already be aware of the show’s obviously puerile humor, was read in those days by millions of kids – and wasn’t sued for doing so. That was and is a major feature of Mad, deflating everything that comes around in pop culture through parody. The fact is, Adjmi’s script is far more pointed and insightful than any episode of Three’s Company and may well work without deep knowledge of the original show, just like the Mad version.

The most recent filing in the Adjmi-DLT situation comes from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, an offshoot of The Dramatists Guild. Like all of the filings in this case, it’s very informative about copyright in general and parody in particular, and it spells out the numerous precedents where the use of a prior work was permitted under fair use, with particular attention to the idea that when the new work is transformative – which 3C surely is – it is permitted (read the complete amicus curiae brief here). In addition to their many examples, I would add from my own misspent youth such works as Bored of the Rings, a 1969 book-length parody of Tolkien by some of the people who would go on to create the National Lampoon, where incidentally, DLDF president John Weidman exercised his own comic skills) and Airplane!, which took its plotline (and punctuation mark) of a poisoned airline crew directly, uncredited, from the 1957 film Zero Hour! More recently, the endlessly touring Potted Potter has successfully run without authorization, though clearly derived from the works of J.K. Rowling and prior to any authorized stage interpretation.

The most recent filing in the Adjmi-DLT situation comes from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, an offshoot of The Dramatists Guild. Like all of the filings in this case, it’s very informative about copyright in general and parody in particular, and it spells out the numerous precedents where the use of a prior work was permitted under fair use, with particular attention to the idea that when the new work is transformative – which 3C surely is – it is permitted (read the complete amicus curiae brief here). In addition to their many examples, I would add from my own misspent youth such works as Bored of the Rings, a 1969 book-length parody of Tolkien by some of the people who would go on to create the National Lampoon, where incidentally, DLDF president John Weidman exercised his own comic skills) and Airplane!, which took its plotline (and punctuation mark) of a poisoned airline crew directly, uncredited, from the 1957 film Zero Hour! More recently, the endlessly touring Potted Potter has successfully run without authorization, though clearly derived from the works of J.K. Rowling and prior to any authorized stage interpretation.

It’s been months since there have been filings for summary judgment in the case (August 2014, to be precise), and according to Bruce Johnson, the attorney at Davis Wright Tremaine in Seattle who is leading the fight on Adjmi’s behalf, there is no precise date by which there will be a ruling. Some might say that I’m essentially rehashing old news here, but I think it’s important that the case remains prominent in people’s minds, because it demonstrates the means by which a corporation is twisting a provision of copyright law to prevent an artist from having his work seen – and that’s censorship with a veneer of respectability conferred by legal filings under the umbrella of commerce. There may be others out there facing this situation, or contemplating work along the same lines, and this case may be suppressing their work or, depending upon the ultimate decision, putting them at risk as well.

We don’t all get to vote on this, unfortunately. But even armchair lawyers like me can see through DLT’s strategy. I just hope that the judge considering this case used to read humor magazines in his youth, which should provide plenty of precedent above and beyond what’s in the filings. 3C may take a comedy and make it bleak, but there’s humor to be found in DLT’s protestations, which are (IMHO) a joke.

P.S. I don’t hold the copyright to any of the images on this page. I’m reproducing them under Fair Use. Just FYI.