January 2nd, 2014 § § permalink

The rise of internet culture has caused many shifts in how we consume information, with one of the more amusing side benefits being the rise of the fictional Twitter user. Disregarding spambots, the anonymity that comes so easily online has birthed such figures as @BronxZoosCobra and @ElBloombito, to name but two. In the theatre realm, the sunny cheerleading of @BroadwayGirlNYC has found adherents, but the sharper tongues (or typing) of @WestEndProducer and @Actor_Friend have launched them into real world publishing, within weeks of each other.

For those who haven’t been following them, a quick précis. West End Producer is, ostensibly, an individual on the production side of theatre in England, whose dishy asides about every aspect of the business always conclude with the simultaneously charming and condescending #dear. I have struck up a Twitter acquaintance with this person, we’ve shared a few jokes and they sent me a signed copy of their book. I’ve noticed their unwavering dedication to chronicling TV talent competitions as they air on weekend evenings (which can be bewildering, since the shows don’t play in the US) and just learned of a mutual passion for Sherlock, but this TV fixation doesn’t suggest someone at the country homes of those with bold faced names on the weekend. I’m newer to Actor Friend, whose full nom de tweet is Annoying Actor Friend, but the online persona is that of a snarky actor, seemingly more of a dedicated gypsy than an above-the-title star. While I won’t guess at gender (though WEP’s appearances in a latex mask disguise would indicate male, and in a book blurb, one writer suggests AF is female), I’d hazard that AF is in their 20s while WEP is likely 30ish (or more).

For those who haven’t been following them, a quick précis. West End Producer is, ostensibly, an individual on the production side of theatre in England, whose dishy asides about every aspect of the business always conclude with the simultaneously charming and condescending #dear. I have struck up a Twitter acquaintance with this person, we’ve shared a few jokes and they sent me a signed copy of their book. I’ve noticed their unwavering dedication to chronicling TV talent competitions as they air on weekend evenings (which can be bewildering, since the shows don’t play in the US) and just learned of a mutual passion for Sherlock, but this TV fixation doesn’t suggest someone at the country homes of those with bold faced names on the weekend. I’m newer to Actor Friend, whose full nom de tweet is Annoying Actor Friend, but the online persona is that of a snarky actor, seemingly more of a dedicated gypsy than an above-the-title star. While I won’t guess at gender (though WEP’s appearances in a latex mask disguise would indicate male, and in a book blurb, one writer suggests AF is female), I’d hazard that AF is in their 20s while WEP is likely 30ish (or more).

In their books Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Acting But Were Afraid To Ask, Dear (Nick Hern Books, £10.99) and #SoBlessed: The Annoying Actor Friend’s Guide To Werking in Show Business (CreateSpace, $13.99), WEP and AF dispense pearls of wisdom in their trademark styles, freed from the chains of 140 characters at a time. Early in each book, one gets the full force of their characters:

“Casting Directors are usually very nice people who like drinking far too much alcohol, and mostly during the day. The ones that don’t drink usually have other habits, which can’t be discussed here – but often end in them being discovered on a bench outside Waterloo Station at 5 a.m.” – West End Producer

“Even after you’ve questionably noted your music, nervously mumbled some directions, and shakily clapped out a tempo, there will be an accompanist who has no effing clue how to play your Jason Robert Brown song. Seriously though – whenever I don’t get a callback, I usually find a way to blame the accompanist. It doesn’t matter if they played my audition flawlessly. It’s still their fault.” – Annoying Actor Friend

“A serious actor has to approach acting in a serious way. This can be achieved by using various methods. One of the easiest ways is by not smiling – particularly if you don’t have good teeth. A serious actor should always save his smile for special occasions. However, this does not mean you can’t smirk. Smirking and smiling are two very different things indeed.” – West End Producer

“As a performer, Annoying Actor Internet Law requires you to read anonymous online opinions about you, take them personally, and then complain about how all those people on theatre message boards are stupid, even though their comments are secretly murdering you from the inside out.” – Annoying Actor Friend

Now you might imagine that an entire book of this arch tone would grow tiresome, let alone two, and I’d readily agree with you. That’s where both of these books turn out to be surprises. #SoBlessed, while the thinner of the pair, both literally and figuratively, pretty much drops all pretense of a character in one of its longer chapters, “On The Road,” which deals with touring. Offering a pointed critique of touring conditions and contracts, AF gets into some detail about the challenges of an actor’s life on tour. AF’s advocacy regarding compensation has taken on even greater urgency among some members of Actors Equity, with the full Twitter support and perhaps instigation of AF, has raised a stir about the pay structure of touring agreements over the holidays.

Now you might imagine that an entire book of this arch tone would grow tiresome, let alone two, and I’d readily agree with you. That’s where both of these books turn out to be surprises. #SoBlessed, while the thinner of the pair, both literally and figuratively, pretty much drops all pretense of a character in one of its longer chapters, “On The Road,” which deals with touring. Offering a pointed critique of touring conditions and contracts, AF gets into some detail about the challenges of an actor’s life on tour. AF’s advocacy regarding compensation has taken on even greater urgency among some members of Actors Equity, with the full Twitter support and perhaps instigation of AF, has raised a stir about the pay structure of touring agreements over the holidays.

Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Acting is more comprehensive than its title suggests, ranging over many fields in the theatre, including producing itself. While the occasional Britishism may befuddle the less worldly reader, the advice dispensed among the punchlines is in fact utterly practical, simply delivered in a tone unlikely to be heard in classrooms at Yale or the Tisch School. “When you audition,” observes WEP, “there’s always a moment when you’re perfect for the role. It’s the moment before you come through the door.” WEP also wraps up the book by enumerating concerns that face the theatre, going beyond flippant remarks about Andrew Lloyd Webber to touch upon rising ticket prices, competition from the electronic media and the need for everyone in theatre “to be braver.”

They may have found their fame in the briefest of missives and gained followings with their dark and knowing wit, but in the end West End Producer and Annoying Actor Friend are both passionately dedicated to the theatre, doling out genuine wisdom and information with nearly every wisecrack. If one is on a budget and has to choose between the books, I give the edge to WEP, even though those in the US have to wait for its release here in the spring via TCG (it seemed to be a favored holiday gift in the UK, judging by my Twitter feed). But both make for irreverent supplements to more staid but perhaps equally inspiring books in theatre. And they are not annoying. Not annoying at all, dear.

June 13th, 2013 § § permalink

I don’t mean to make anyone paranoid, but if your organization has unpaid interns, you need to start thinking about whether they may start legal proceedings against you for back pay. In the wake of a federal court ruling that found Fox Searchlight Pictures violated minimum wage laws in their engagement and utilization of unpaid interns, any number of shrewd interns may well be considering their options even as I write.

I don’t mean to make anyone paranoid, but if your organization has unpaid interns, you need to start thinking about whether they may start legal proceedings against you for back pay. In the wake of a federal court ruling that found Fox Searchlight Pictures violated minimum wage laws in their engagement and utilization of unpaid interns, any number of shrewd interns may well be considering their options even as I write.

‘Well that’s Hollywood,’ you respond, ‘They’ve got piles of money and absolutely should have been paying their interns.’ But the minimum wage laws, in existence for years, don’t consider the assets of any company in deciding whether an internship is legitimate, only whether the proper criteria apply. While I’m no labor lawyer, I have long been familiar with the general guidelines of internships, which in essence say that an unpaid internship is legitimate only when there is a clear educational benefit to the intern (best ascertained when the internship is approved for academic credit, not by a ‘they get to see how things work while doing the copying’ justification) and when the internship does not involve labor that would otherwise have to be undertaken by a paid employee.

As Isaac Butler astutely points out on his blog this morning, the arts (and no doubt countless other businesses, both commercial and not-for-profit), operate under “an assumption of not paying people, with narrow, specific contexts as to when that won’t be the case.” Internships are ingrained in our culture and the resistance to change is due in part to the mindset of ‘that’s what I did when I was young and it should still be that way today.’ This same logic long ruled over medical education, with doctors-in-training working insane hours as if under some prolonged fraternity hazing – until people started noticing that patients were dying as a result. ‘That’s the way it’s always been done’ is not a legitimate excuse.

No one may be dying because of unpaid arts internships, but the legal and ethical issues are certainly brought to the forefront by the court ruling. Organizations are well advised to review their intern practices against the wage guidelines and applicable laws as soon as possible; this is not a blanket jeremiad against internships, only those which aren’t legit. On the upside, perhaps this new finding (again, based on long-standing laws) will prompt more organizations to develop and institute true internships, with defined training regimens for a limited time. Still other companies may realize it’s smarter to begin paying at least minimum wage as soon as possible. (Don’t get hung up on your personal interpretation of what “stipend” means; that’s another easy out, and a trap.)

Of course if those employees are full time, you’ll have to provide benefits as well, such as health insurance and paid time off, so minimum wage times 40 hours a week is only part of the true price tag here. While in the short term, absorbing these costs will l be difficult, it beats the looming prospect of legal action, resulting in not only making payments in arrears, but also bearing the burden of penalties. Whatever your company considers, get professional counsel to make sure you’re doing not just the right thing, but the correct thing.

Some may choose to debate whether the transition away from unpaid internships/jobs will place a greater burden on smaller companies. As a veteran of what most would consider large organizations, it’s difficult for me to assess the relative impact. I would certainly hate to see small or even nascent companies derailed, but as we’re taught, ignorance of the law (or willfully ignoring it) is no excuse for breaking it (a recent employment tribunal in England has prompted a reexamination of unpaid fringe theatre work). The arts ecosystem must absorb the lessons of the Fox Searchlight decision and, as a field that is perpetually challenged, we will find our way through. Indeed, we may ultimately be stronger, since in many cases, it is only young people of means who can afford to work for nothing; this will be a step (though by no means the whole solution) in insuring that arts careers are available to everyone.

Although unemployment rates are down, it’s well known that job opportunities for recent college graduates are still relatively slim, and it’s not unusual for young people to do multiple internships on their way to paid work. The current arts internship culture benefits from that harsh reality, since the demand for entry-level opportunities is possibly even greater than in the past, when internships and apprenticeships were already the norm, especially in glamour industries. Though it may not seem that way day in your day to day tasks, every single arts job is in fact part of a glamour industry – it’s not reserved for movies, TV, fashion, sports and publishing. But the nation’s economic issues, our own belief in the inherent value of the arts, and the unending stream of people desperate for their show business break, should not be used as a reason to avoid paying those who are, for all intents and purposes, employees.

* * *

Update, 4 pm, June 13: Hours after I posted this story, The New York Times reported on two interns filing suit against Condé Nast for underpayment of wages for summer internships over the past several years. This situation will only keep growing with each filing, and with each success by plaintiffs.

Full disclosure: I am a relative rarity in the arts, in that I never had any unpaid employment in my career. My financial aid package in college included 20 hours of “work study” each week beginning with my freshman year, which paid me minimum wage to work in the box office of the campus performing arts center, home to several professional companies. I parlayed that position into a public relations gig at a small professional company during my junior year, at the rate (as I recall) of $4 an hour. I was extremely fortunate to have had these jobs, as I knew my parental support was to end the day I graduated, and these opportunities set me up to start full employment immediately, since I already had professional experience.

May 22nd, 2013 § § permalink

My parents were not theatergoers and my youthful memories are not filled with reveries of family trips to New York to see shows. I can remember being taken to the theatre only twice as a youth by my parents, once in 1969 in New Haven (Fiddler on the Roof, national tour) and once in about 1975 on Broadway (The Magic Show). Yet there was something embedded in my DNA which made me interested in performance; I was writing plays (almost all adaptations of existing works) in elementary school with very little frame of reference and undoubtedly even less skill.

My parents were not theatergoers and my youthful memories are not filled with reveries of family trips to New York to see shows. I can remember being taken to the theatre only twice as a youth by my parents, once in 1969 in New Haven (Fiddler on the Roof, national tour) and once in about 1975 on Broadway (The Magic Show). Yet there was something embedded in my DNA which made me interested in performance; I was writing plays (almost all adaptations of existing works) in elementary school with very little frame of reference and undoubtedly even less skill.

I longed to be an actor, and vividly remember my envy of Danny Bonaduce on The Partridge Family, thinking if he could be on TV, so could I. This was a bit odd, because I was a rather socially awkward child who didn’t mix well with most kids in my elementary years; I read constantly and had to be pushed outside into fresh air, where I invariably kept reading. Unlike many drawn to performing, music didn’t have a big role in my childhood, outside of Top 40 AM fare once I had my own little transistor radio. My parents didn’t have a record collection to speak of; I do recall my mother’s beloved two-disc set of Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, and some assorted children’s records, such as the Mary Poppins soundtrack and Danny Kaye’s Mommy, Give Me a Drink Of Water and Tubby the Tuba. Cast recordings, which loom large in the memories of theatre pros, were absent, save for Fiddler on the Roof (culturally imperative, but rarely played) and West Side Story (likewise, but we only listened to “Dear Officer Krupke”).

I longed to be an actor, and vividly remember my envy of Danny Bonaduce on The Partridge Family, thinking if he could be on TV, so could I. This was a bit odd, because I was a rather socially awkward child who didn’t mix well with most kids in my elementary years; I read constantly and had to be pushed outside into fresh air, where I invariably kept reading. Unlike many drawn to performing, music didn’t have a big role in my childhood, outside of Top 40 AM fare once I had my own little transistor radio. My parents didn’t have a record collection to speak of; I do recall my mother’s beloved two-disc set of Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, and some assorted children’s records, such as the Mary Poppins soundtrack and Danny Kaye’s Mommy, Give Me a Drink Of Water and Tubby the Tuba. Cast recordings, which loom large in the memories of theatre pros, were absent, save for Fiddler on the Roof (culturally imperative, but rarely played) and West Side Story (likewise, but we only listened to “Dear Officer Krupke”).

So I’ve often wondered how I managed to be cast in lead roles in each and every show (save one) that I auditioned for in junior high, high school, community theatre and college, and why being on stage or in speaking in front of large groups has never frightened me. I’ve come to understand that part of the appeal, and the ease, came from the stage offering the exact opposite of day to day life. On stage, I always knew what to say and when to say it, and when I did it right, I was rewarded with laughter and applause. It was a startling contrast from the uncertainty of casual interaction. Where did I learn this skill? Comedy records.

So I’ve often wondered how I managed to be cast in lead roles in each and every show (save one) that I auditioned for in junior high, high school, community theatre and college, and why being on stage or in speaking in front of large groups has never frightened me. I’ve come to understand that part of the appeal, and the ease, came from the stage offering the exact opposite of day to day life. On stage, I always knew what to say and when to say it, and when I did it right, I was rewarded with laughter and applause. It was a startling contrast from the uncertainty of casual interaction. Where did I learn this skill? Comedy records.

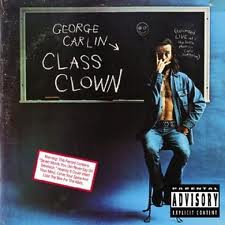

As a tween and teen in the early 70s, in the pre home video era, I was completely entranced by comedy recordings both current and from the relatively recent past. My brother and I came together primarily over our basement record player and the comedy collection scavenged from yard sales (and Monty Python on PBS). We had a bunch of the earliest Bill Cosby albums, the deeply politically incorrect Jose Jimenez In Orbit, a Smothers Brothers disc and (purchased new, smuggled in) George Carlin’s AM/FM and Class Clown. These are the ones that come to mind; there may have been more.

As a tween and teen in the early 70s, in the pre home video era, I was completely entranced by comedy recordings both current and from the relatively recent past. My brother and I came together primarily over our basement record player and the comedy collection scavenged from yard sales (and Monty Python on PBS). We had a bunch of the earliest Bill Cosby albums, the deeply politically incorrect Jose Jimenez In Orbit, a Smothers Brothers disc and (purchased new, smuggled in) George Carlin’s AM/FM and Class Clown. These are the ones that come to mind; there may have been more.

We listened to these albums over and over as if they were music, and reached the point where we knew entire routines by heart. Not just the words, but the pacing, the inflections, the comics impersonations of other characters and performers. Each routine was a song, and we would recite along with the records. We worked to perfect Carlin’s Spike Jones “hiccup” before we’d ever heard a Spike Jones record. We were mesmerized by them, long after the surprise of the jokes had faded; of course, the contraband Carlin album made us very adventuresome among our peers because of its “dirty” language (we were perhaps 12 or 13 at the time).

We listened to these albums over and over as if they were music, and reached the point where we knew entire routines by heart. Not just the words, but the pacing, the inflections, the comics impersonations of other characters and performers. Each routine was a song, and we would recite along with the records. We worked to perfect Carlin’s Spike Jones “hiccup” before we’d ever heard a Spike Jones record. We were mesmerized by them, long after the surprise of the jokes had faded; of course, the contraband Carlin album made us very adventuresome among our peers because of its “dirty” language (we were perhaps 12 or 13 at the time).

I never of thought about these records as scripts, but they were almost sacred texts to us. If we learn to perform first by imitating and later by finding our own style, then we were taking a suburban master class from performers at places like The hungry i in San Francisco before we’d ever been on an airplane and before we would have been old enough to gain admittance even had we managed the trek. The lessons ran deep: a couple of years ago, a gift set of Carlin CDs accompanied me on a road trip, and my wife was both amused and annoyed by my ability to recall every moment with precision, despite my not having heard the material in many years. Did I ever find a style of my own, moving beyond mimicry? That’s for others to say.

My actual performing years were brief, covering 1977 to 1981, 10 shows in all. I was perhaps the fussiest Oscar Madison in history, since most see me as a Felix; I probably shouted more than any one of the 12 Angry Men as Juror 3; I managed to make the characters of Will Parker and Albert Peterson the most inept dancers in their history. I suspect I was best in roles that called for comedy over movement or voice: the Woody Allen stand-in Axel Magee in Don’t Drink The Water, the meek Motel Kamzoil in Fiddler, and the dirty old man Senex in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum (my college’s newspaper noted a distinct Jewish paternalism in my performance at age 19). Whatever I had, I owed not to the performers from the Golden Age of Theatre, who I would only come to know later, but to the stand-up comedians who were the writers and performers I took close to heart – if for no other reasons than that they were repeatedly accessible on the technology that was available to me.

My actual performing years were brief, covering 1977 to 1981, 10 shows in all. I was perhaps the fussiest Oscar Madison in history, since most see me as a Felix; I probably shouted more than any one of the 12 Angry Men as Juror 3; I managed to make the characters of Will Parker and Albert Peterson the most inept dancers in their history. I suspect I was best in roles that called for comedy over movement or voice: the Woody Allen stand-in Axel Magee in Don’t Drink The Water, the meek Motel Kamzoil in Fiddler, and the dirty old man Senex in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum (my college’s newspaper noted a distinct Jewish paternalism in my performance at age 19). Whatever I had, I owed not to the performers from the Golden Age of Theatre, who I would only come to know later, but to the stand-up comedians who were the writers and performers I took close to heart – if for no other reasons than that they were repeatedly accessible on the technology that was available to me.

I do not suggest that aspiring performers should run out and start learning comedy albums by heart, though one could do worse for understanding timing and pace. Of course, now we can watch and not merely listen to comedians and work out their full routines step by step; I wonder whether the visuals would have added to our mimicry or distracted us from the deep concentration on words and delivery that took place as a ritual in our cluttered basement, our nightclub of the mind. But I am sure of one thing: there are many ways to find one’s way to the stage, and mine was through the storytelling and punchlines of some modern masters of the comedy genre.

I do not suggest that aspiring performers should run out and start learning comedy albums by heart, though one could do worse for understanding timing and pace. Of course, now we can watch and not merely listen to comedians and work out their full routines step by step; I wonder whether the visuals would have added to our mimicry or distracted us from the deep concentration on words and delivery that took place as a ritual in our cluttered basement, our nightclub of the mind. But I am sure of one thing: there are many ways to find one’s way to the stage, and mine was through the storytelling and punchlines of some modern masters of the comedy genre.

P.S. My vocal coaches were Tom Lehrer, Stan Freberg, and Allan Sherman. But that’s another story.

March 12th, 2013 § § permalink

There’s a high school musical in jeopardy? Quick, to the Howardmobile.

I’m kidding, of course. But when I got an e-mail at 11:30 a.m. yesterday, saying that parents and groups were going to protest a production of Sweeney Todd at Amity Regional High School in Woodbridge CT at that evening’s board of education meeting, I was extremely, nerve-janglingly upset. While I have spoken out against censorship of high school productions before, most vocally in Waterbury CT, and written about other such efforts as well, this threatened action struck a bit too close to home.

Howard’s back. And this time it’s personal.

Amity was my high school, where I acted in six shows between 1977 and 1980, where I was recognized for my professional work in theatre by being inducted into the school’s “hall of fame.” I was still in high school when I saw the original Broadway production of Sweeney Todd with a group of friends, chaperoned by one of our English teachers. Second only to Buried Child, Sweeney was a major part of why I chose a career in the theatre.

I happen to have Angela Lansbury right here.

I immediately reached out to the drama teacher, the school’s principal and a member of the school board. My instinct was to rush up to the meeting to speak on behalf of the show, but I didn’t want to inflame the situation, or be seen as an outsider, carpetbagging my way into a local issue. I also didn’t want to go if I wouldn’t be allowed to speak. In the meantime I thought, ‘Dammit, if only I had a day’s notice. I would call Hal, I would try to reach Mr. Sondheim, to gather letters of support. I even checked my “world clock” to see what time it was in Australia, where Angela Lansbury is currently performing in Driving Miss Daisy. Alas, she was presumably asleep, and likely wouldn’t rise before the board of ed meeting; otherwise, she is a rapid e-mail responder.

I immediately reached out to the drama teacher, the school’s principal and a member of the school board. My instinct was to rush up to the meeting to speak on behalf of the show, but I didn’t want to inflame the situation, or be seen as an outsider, carpetbagging my way into a local issue. I also didn’t want to go if I wouldn’t be allowed to speak. In the meantime I thought, ‘Dammit, if only I had a day’s notice. I would call Hal, I would try to reach Mr. Sondheim, to gather letters of support. I even checked my “world clock” to see what time it was in Australia, where Angela Lansbury is currently performing in Driving Miss Daisy. Alas, she was presumably asleep, and likely wouldn’t rise before the board of ed meeting; otherwise, she is a rapid e-mail responder.

What we have here is a failure to communicate

When I was told by the school board member who I had contacted that my voice would be welcomed at the meeting, I did rush to rent a car. While the bright blue Honda hybrid from Zipcar was hardly the Batmobile, it whisked me to Connecticut, filled with a sense of purpose, as I thought all the while of what to say. I hadn’t had time to write anything; I was going to have to wing it. ‘Avoid inadvertent puns,’ I told myself. ‘Remember you can’t say that the opposition is half-baked, or that this is an issue of taste. You can’t risk inadvertent laughter. Listen and respond to the other speakers. Don’t talk about yourself. This is about the show, the school and the kids.’

No man is a failure who has friends

Thanks to Twitter and Facebook, there was rapid circulation of the situation among many people with whom I went to high school, and though I drove up on a lone mission, I was ultimately joined at the meeting by one of my drama club friends and by my sister, whose older daughter is a senior in the school. My brother, with whom I was not on speaking terms during high school, apologized that he couldn’t be at the meeting to support me and support the production. I learned that one of the “parent liaisons” to the drama club was the sister-in-law of one of my very closest friends and she welcomed me with a hug; her daughter is the stage manager for Sweeney Todd. The Facebook network reached out into the Connecticut media, resulting in a TV crew from the NBC affiliate; my own tweets and Facebook notice alerted The New York Times to the story.

They agreed to a sit-down

The meeting about the drama group was, ultimately, not one of high drama. A member of the clergy spoke first, saying her reservations arose from an interfaith leadership meeting two weeks prior, at which there was discussion about how to curb representations of violence, in the wake of the Newtown massacre. Several parents questioned the choice of the play and wondered whether there weren’t other vehicles available. One of those parents had a child in the show, and she wasn’t pulling her child from it, despite her own reservations. Others spoke of the story’s long history, of the musical’s fame, of the high regard in which Stephen Sondheim is held. So even when I stood up, with notes scribbled moments before, I was not in a lion’s den, but in the midst of a respectful exchange of ideas. (A balanced report appeared in The New Haven Register this morning.)

And so, from my off-the-cuff, at times ungrammatical, remarks: “Stephen Sondheim, who has already been lauded here, is very famous for a song that he wrote in another one of his other musicals in which we hear the line ‘Art isn’t easy.’ Creating art isn’t easy and the content of art isn’t easy…Sweeney Todd can create a learning opportunity. The responsibility of schools is to create a context for young people to understand the world around them and as much as we may want to keep that world away for as long as possible, it is not possible. While we can choose to do other works of literature, to read other books, to sing other songs, we are denying them the opportunity to learn.”

Stand down, but remain alert

No one demanded that the show be stopped. No vote was asked for or taken, and the board listened without response, since the whole discussion was not on the official agenda, but was merely part of “public comment.” To call it civil suggests a frostiness I did not feel, to call it polite suggests underlying anger. Might there be repercussions down the line, as some seek to exert authority over what can and can’t be performed in future years? That’s possible. If so, if welcome, I’ll be at those meetings as well.

I noted in my remarks that this was not an isolated incident, that censorship of high school theatre happens all too often. Some may dismiss it as merely a school problem, but it is important to anyone who loves theatre or believes in the value of the arts. Yes, I have taken up the cause of allowing students to grapple with challenging material before, and while yesterday struck particularly close to home, I’ll speak out in support of threatened high school drama whenever I hear about opposition (sorry, no Grapes of Wrath paraphrase at this point).

But I have only one hometown, one high school. The only way we can insure freedom of expression, freedom in the arts in teens – who will be our future artists and our future audiences – is if we are all aware of what is taking place near us, or back home, and if we speak out.

* * *

Addendum, March 16, 10 am: On the Friday immediately following the Board of Education meeting described above, which took place on a Monday evening, Dr. Charles Britton, principal of Amity Regional High School, sent the following e-mail to the district. I hope it becomes a model for other schools that face such challenges:

“This past week, the media widely reported some objections that have been raised against this year’s spring production of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Some members of the Amity community and parents believe this production is too graphic for a high school audience. The administration and Drama Department at Amity High School respectfully disagree with these objections. The production is PG-13 and designed for a high school level audience. The show is produced in high schools across the nation. When carefully considering all academic material for Amity students, the faculty and administration at Amity never select material that is gratuitously violent or purposefully titillating in nature. All material is selected for the deeper meaning and value of the work of art, literature, or related academic resource. In the hands of talented teachers and directors, this academic material engages students more effectively and promotes our efforts to stimulate critical and creative thinking.”

* * *

Addendum, March 16, 3 pm: I have discovered some additional local reporting on the Sweeney Todd discussion, and will provide links with no comment, other than to say that it is worth reading not only the articles, but the comments that follow each of them. It is also worth noting which outlets reported from the event, and which reported solely from other news reports.

“Controversy Over Sweeney Todd: Let’s Take a Breath Here,” from The Naugatuck Patch, March 11

“Sweeney Todd Pros and Cons Aired at Amity High,” from The Orange Patch, March 12

“Sweeney Todd Protest: Residents Denounce Staging of Violent Musical at Connecticut High School,” from The Huffington Post, March 12, updated March 14

February 11th, 2013 § § permalink

If you are looking to read yet another blog post filled with snark for, or describing the “hate watching” of, the television series Smash, this is not the post you’re looking for. Move along.

If you are looking to read yet another blog post filled with snark for, or describing the “hate watching” of, the television series Smash, this is not the post you’re looking for. Move along.

With the second season of Smash now underway, to precipitously underwhelming ratings, I’d like to discuss for a moment how it has been received among the people I discuss it with most often, namely theatre professionals. There’s no shortage of criticism of the show from every angle , but I don’t know that I’ve seen anyone get at the overriding sentiment within the theatre community.

In a word: disappointment.

Just over a year ago, many theatre people were thrilled at the idea that a network television series would portray their lives on a weekly basis. Sure, it was loaded with the glitz and glamour that’s typically associated with commercial Broadway theatre, which is only a small portion of American theatrical production, but it was still theatre. Unlike cops, lawyers, private detectives, forensic analysts, doctors and many other professions, we don’t see shows focused the act of making theatre on American television. Maybe we’d finally get a chance for our stories to be told.

Yes, we’ve had a couple of “reality shows” about casting for actual theatre productions (Grease and Legally Blonde). There have been characters who work in theatre: Joey on Friends, Annie on Caroline in the City, Maxwell Sheffield on The Nanny. But Smash held the potential for being the U.S. counterpart to the Canadian series Slings and Arrows, little seen in its original U.S. airing but now a beloved touchstone for so many.

There are certainly many people in the business who are delighted to see Smash showcasing theatre talent and sharing it with the rest of the world (actors like Wesley Taylor, Krysta Rodriguez, Leslie Odom Jr., Jeremy Jordan and Savannah Wise; composers like Joe Iconis and Pasek & Paul) and people watch to cheer on friends and acquaintances. There’s also the frisson of recognition when real-life figures like Jordan Roth and Manny Azenberg turn up, in cameos meaningful to a very small number of potential viewers, but a treat for the insiders. Yet as the series has progressed, I’ve talked increasingly with the disaffected, who stopped watching, and the hopeful, who watch dubiously but religiously, with optimism that their dreamed of ideal may still appear.

There’s a recent corollary here, and that’s with the HBO series The Newsroom. When it debuted, I read scathing review after scathing review and one journalist friend even asked me if I had any idea why he hated it so much. “Because,” I explained, “You live the reality, and what’s on screen isn’t that.” I suspect that was the overriding sentiment behind so many of the Newsroom reviews, because (of course) they were written by journalists. And that’s the same scenario for Smash among theatre people.

There’s a recent corollary here, and that’s with the HBO series The Newsroom. When it debuted, I read scathing review after scathing review and one journalist friend even asked me if I had any idea why he hated it so much. “Because,” I explained, “You live the reality, and what’s on screen isn’t that.” I suspect that was the overriding sentiment behind so many of the Newsroom reviews, because (of course) they were written by journalists. And that’s the same scenario for Smash among theatre people.

Let’s face it, scripted television programming isn’t documentary, and for that matter, neither is reality TV. It’s created, contrived, scripted, edited and so on in order to compress plots into rigid time constrictions, with the goal of entertaining as many people as possible. So it is with Smash.

I wonder what police officers make of, say, The Mentalist. Can they detach from reality and enjoy the fiction? Were doctors watching House for diagnostic refreshers? Was Sam Waterston giving a master class in prosecutorial technique all those years on Law and Order? I wouldn’t be surprised if professionals find something laughable every week, but those staples of TV drama have been around since the days of Dragnet, Ben Casey and Perry Mason, so they’re probably so much wallpaper by now.

Journalists at least had Lou Grant (the series) once upon a time, but to be fair, they’re most often seen on TV as plot devices, often portrayed as nuisances, or worse still amoral. Theatre people are typically portrayed as elitists or egotists for comic effect, so we don’t have TV icons they can point to very easily, outside of performances and great speeches on The Tony Awards. Anyone remember the laugh-fest when Law and Order: Criminal Intent did its version of Julie Taymor and Spider-Man: Turn Off The Dark? That’s our usual lot.

However inaccurate TV series may be, there’s no denying the fact that a hit series can have profound real-world impact. Since the launch of the CSI franchise, forensic science programs have ballooned in popularity; it’s hard not to watch a series like Blue Bloods and feel that a sense of bravery, duty and honor pervades police work. In real life, Greg House would likely have been fired after episode two, but people were mesmerized by a talented diagnostician whose only solace in a screwed up life was to cure diseases, even if it usually meant making vast mistakes until the last 10 minutes – for the sake of drama. There’s no denying that the cops on Law and Order: SVU want to get justice for victims, or that the doctors on ER wanted to save lives; they may be flawed, but they have real commitment. What do the characters on Smash represent?

Smash has tantalized with the “show” part of show business, while the business part is startlingly underrepresented (I’ll never forget the first episode of Slings and Arrows, when a managing director had a meeting with a corporate sponsor and I saw my life’s work on screen for the very first time). More importantly, it hasn’t given us any heroes; I wonder whether the show will actually inspire anyone to go into the theatre.

Smash has tantalized with the “show” part of show business, while the business part is startlingly underrepresented (I’ll never forget the first episode of Slings and Arrows, when a managing director had a meeting with a corporate sponsor and I saw my life’s work on screen for the very first time). More importantly, it hasn’t given us any heroes; I wonder whether the show will actually inspire anyone to go into the theatre.

And that, of course, is what I suspect we all hoped for, a mass media means of showing the world at large what an exciting, challenging, difficult, compelling, fulfilling life can be had in the theatre. Journalists surely long for a weekly platform that reinforces the necessity of properly funded investigative reporting, and I’d certainly like to see a show that reminds us why teachers are the cornerstone of this country’s future, a latter-day Room 222, in contrast to the way politicians now paint them.

We’re probably too emotionally invested in Smash. It was probably never going to be a recruiting tool for theatre or the arts, or finally explain to our families why we do what we do. That’s the stuff of public service announcements, not drama, not mass entertainment. But it’s in our nature to dream, isn’t it? And every so often in our line of work, we make dreams come true.

So, whatever comes of Smash this season, whether it runs or wraps up, whether you love it or loathe it, I leave you with this thought: here’s to season four of Slings and Arrows. May it come soon.

October 16th, 2012 § § permalink

As I sat at last week’s session of The Shakespeare Forum, watching performers present monologues that led to highly supportive critiques from some 50 gathered peers, I was bombarded by thoughts.

As I sat at last week’s session of The Shakespeare Forum, watching performers present monologues that led to highly supportive critiques from some 50 gathered peers, I was bombarded by thoughts.

Most immediate, of course, were my reactions to the presentations. While the format was for everyone present to feel free to ask questions and make observations, I spoke only once in the two hours, a single query limited to seven words. I might have engaged more, but as a newcomer, I was uncertain as to how to best frame my comments in this protective environment. Consequently, I became contemplative.

I had, needless to say, my own responses both to what was performed and the recommendations that followed. While I am no critic, I can be highly critical, but this was no place for the snap reactions that come upon seeing a finished show. I was watching people test their talents, as others sought to teach and learn from the conversations that ensued. Yes, I wanted to tell one woman that in an audition, it was highly unlikely that she could clutch the wall as she did; I wanted to share with one man that by his posture and position, I had guessed he was about to perform something from Hamlet even before he spoke; I wanted to debate some of the suggestions as wrong-headed. But that was what I wanted to say in the moment, out of habit, not necessarily what anyone in that room needed.

My thoughts turned to my unfortunate tendency to verbalize perceived flaws first; then I began to worry whether I was watching too intently. I have an unconquerable tendency to furrow my brows when I concentrate, which I have often been told makes me look angry when I am anything but. The last thing this room needed was negative expression of any kind.

As suggestions and admiration flowed, I wandered back to my two collegiate efforts at directing, which no doubt had all the finesse that an untrained, unschooled 19-year-old (who looked angry when thinking) brought to the table, which is to say almost none. Yes, at that age we’re all learning, but how brusque I must have been, how unsupportive, in pursuit of the production I saw in my head.

When the Forum group, as advised, snapped their fingers in support of statements they heard to express concurrence without interrupting to verbalize agreement, I realized that I had no idea whether this was a common practice in theatre courses and workshops, or whether this was something unique to The Shakespeare Forum. What else do I not know about performers’ education? This was simple; surely there were processes more profound.

I even was thrown back to the extreme awkwardness of my high school years as I realized how many in this group came regularly, and knew each other well, fostering safety. I was once again the awkward outsider, unsure of how to act except when with my own friends. Yet my discomfort was surely nothing compared to those who came to give voice to monologues, perhaps for the first time in front of others. Did I have that courage, as I did, irrepressibly, in my high school performing days?

Finally and most importantly, I realized how long it had been since I was “in the room,” that is to say, an actual rehearsal. As someone who chose theatre as a profession based on my love of the form, and my deep desire to play some constructive role in it, I was reminded as I sat on a folding chair in a basement room south of Canal Street that as my career advanced, I had extraordinary opportunities to see productions, but that the actual process of making theatre had become distant. I was reminded that for as much as I may know about the business and even perhaps the art, I’ve never been schooled in nor benefited from the practical experience of speaking the language of the classroom, rehearsal room, the audition, the performance. I was a stranger in my own land.

This week, Michael Kaiser of The Kennedy Center wrote of his belief that arts managers are frequently too content in their jobs to be creative, and I challenge that assertion on the grounds of sweeping generalization. While I have no doubt that, as in any profession, there are those who are always growing and learning and those who find comfort in the status quo, arts administrators are always grounded in creativity, namely the work they support. Do some grow too complacent? Perhaps. But the ever-changing financial and entertainment environments virtually dictate that creativity is at the forefront of administrators’ and producers’ thoughts, as they struggle the sustain the frameworks that allow for production.

But rather than sweepingly and publicly castigating an entire class of arts professionals, I find it more constructive to offer a suggestion to ward against any potential stagnation, because of last week’s experience: namely that arts administrators must find the time, on a regular basis to get back “in the room,” namely the rehearsal room. It’s thrilling to work on behalf of great productions, but the core of what we are a part of is there within the drab beige walls, the mocked up scenery, the conversation, the camaraderie, the repetition and the revision. That is one essential part of the administrator’s continuing education, sustenance and success.

Even within a construct aimed at developing actors’ skills, not leading to any particular production or even necessarily to a better audition piece, my visit to The Shakespeare Forum, unexpectedly, unintentionally even, showed me some fundamentals of theatre, my chosen profession. I have no doubt that this would hold true in music, in dance, in opera, and so on. As administrators, we try to create simulacrums of this integral work – the master class, the open rehearsal, the invited tech – for our audiences, for our donors, for the media, to stimulate their knowledge, their loyalty, their generosity. But as insiders, we have access to the real thing. I urge everyone to use it.

I, for one, can’t wait to get back in the room again. I look forward to seeing you there.

September 24th, 2012 § § permalink

I don’t know that I saw Kilty during the last 20 years of his life. Perhaps we ran into one another in a few theatre lobbies, I would occasionally hear a little something about his health, but he was long out of my mind and, I fear, the minds of many others who knew him during his lengthy theatrical career. So when I first saw a news story from a small Connecticut publication reporting that he had died, at age 90, in a car crash, I surprised myself with the depth of my feeling.

I don’t know that I saw Kilty during the last 20 years of his life. Perhaps we ran into one another in a few theatre lobbies, I would occasionally hear a little something about his health, but he was long out of my mind and, I fear, the minds of many others who knew him during his lengthy theatrical career. So when I first saw a news story from a small Connecticut publication reporting that he had died, at age 90, in a car crash, I surprised myself with the depth of my feeling.

I had met Jerome Kilty immediately upon my college graduation, when I went to work as a press assistant at the Westport Country Playhouse. Kilty (as many called him when speaking of, not to, him) was part of the Westport theatre crowd, a fairly tight-knit group of theatre pros who had moved to the Connecticut countryside in the 50s and 60s, long before its main street became lined and littered with chain stores, before big box stores cropped up along once bucolic Route 1. He only performed at Westport once during my two summers there – a benefit reading of his own Dear Liar, playing the role of George Bernard Shaw – but he seemed to be around so often, an impression helped, no doubt, by the schedule of 11 shows in 11 weeks, meaning opening nights every Monday between June and August, the central event of Westport’s theatrical social circle. Then, magically, when I went to Hartford Stage, there was Kilty again, acting in the first show of the season and acting and directing in the third, the former a Shakespeare play, the latter a Shaw.

Kilty was a character from another era – actor, director, playwright; a man who had worked with the stage greats of the 50s, who had founded theatres and, with Dear Liar, written theatre’s most successful epistolary two-hander (until Pete Gurney overtook him with Love Letters). I remember sitting in my little office as he told me the story of his army leave in England, when he trekked to George Bernard Shaw’s home and, denied an audience with the great man, how he scooped some pebbles from Shaw’s driveway as keepsakes and how they still sat on his mantel as we spoke. The people we meet at this age make such an outsized impression when they deign to give us their attention, their time, their interest. Kilty embodied the perfect English gentleman – which is ironic since, as I would learn, he had been born on a California Indian reservation.

When I read of Kilty’s death, I knew that he left no survivors and I feared that his passing would go largely unnoticed, which struck me as profoundly sad, for a man of accomplishment. Having been raised in the climate of old media, I felt that he was deserving of a New York Times obituary, an honor he would have appreciated. So I forwarded to news story to the theatre editor, commenting that this was a man worthy of a final recognition. I made a few calls, I wracked my own memories, and provided what little material I could when called by the reporter working on the piece, all the while feeling inadequate to the task, regretful that I had not seen this lovely man in so very long, and determined that he have this one last moment in the spotlight.

The Times did well by Kilty, and I think that the reporter, Dennis Hevesi, was as charmed by Jerry, even in death, as I was in my youth several decades ago. I was so pleased to see this final remembrance, and both pleased and surprised when, on a Sunday morning in southern New Jersey, I saw it as well in the pages of The Philadelphia Inquirer, via the Times news wire. Perhaps it appeared in many other papers and websites (previously, Robert Simonson had written an even more thorough article for Playbill); perhaps it reached others long out of touch but who took a moment to commemorate Kilty privately when they learned of his passing.

I write this not out of pride in my role in this obituary, or to demonstrate that I can contact the right people at the Times. I know that the decision to write about Kilty was ultimately theirs, based on the merits of his life, his achievements. I write because I am lucky to have known Kilty, and never let him know I felt that. I write because I wonder how many theatre artists are forgotten – even before they pass away – and how many may never be given a final bow when they leave us? I am thinking, even now, of others who were kind and generous to me as I began my career, and how I don’t wish to only do them honor when they pass, but to reconnect with them while I, and they, are still able. I think about how, as I grow older, these opportunities will become fewer with every passing year, until I find myself hoping that I am, in some small way, remembered.

We know that theatre is an impermanent art form, as closed productions linger only in the pages and digital memories of journalism, and in the minds of those who saw them. The lives of theatre artists are fleeting as well, and we must honor not only the perpetually famous, but those who have committed their lives to this life, with dedication and talent but perhaps without fame, while they live, so their deaths don’t come as a surprise that triggers reveries and regrets, but as the finales of friends, remembered not from years past, but from our own recent present.

September 6th, 2012 § § permalink

Every January, the media run features on how to lose those holiday pounds. As schools let out for the summer, the media share warnings about damage from the sun and showcase the newest sunscreens. In Thanksgiving, turkey tips abound.

Every January, the media run features on how to lose those holiday pounds. As schools let out for the summer, the media share warnings about damage from the sun and showcase the newest sunscreens. In Thanksgiving, turkey tips abound.

For theatre, September reveals two variants of its seasonal press staple, either “Stars Bring Their Glamour To The Stage,” or, alternately, “Shortage of Star Names Spells Soft Season Start.” Indeed, the same theme may reappear for the spring season and, depending upon summer theatre programming, it may manage a third appearance. But whether stars are present or not, they’re the lede, and the headline.

The arrival of these perennial stories is invariably accompanied by grousing in the theatre community about the impact of stars on theatre, Broadway in particular, except from those who’ve managed to secure their services. But this isn’t solely a Broadway issue, because as theatres — commercial and not-for-profit, touring and resident — struggle for attention alongside movies, TV, music, and videogames, stardom is currency. Sadly, a great play, a remarkable actor or a promising playwright is often insufficient to draw the media’s gaze; in the culture of celebrity, fame is all.

But as celebrity culture has metastasized, with the Snookis and Kardashians of the world getting as much ink as Denzel and Meryl, and vastly more than Donna Murphy or Raul Esparza, to name but two, the theatre’s struggle with the stardom issue is ever more pronounced. Despite that, I do not have a reflexive opposition to stars from other performing fields working in theatre.

Before I go on, I’d like to make a distinction: in the current world of entertainment, I see three classifiers. They are “actor,” “celebrity,” and “star.” They are not mutually exclusive, nor are they fixed for life. George Clooney toiled for years as a minor actor in TV, before his role on ER made him actor, celebrity and star all in one. Kristin Chenoweth has been a talented actor and a star in theatre for years, but it took her television work to make her a multi-media star and a celebrity. The old studio system of Hollywood declared George Hamilton a star years ago, but he now lingers as a celebrity, though still drawing interest as he tours. Chris Cooper has an Oscar, but he remains an actor, not a star, seemingly by design. And so on.

So when an actor best known for film or TV does stage work, it’s not fair to be discounting their presence simply because of stardom. True stardom from acting is rarely achieved with an absence of talent, even if stardom is achieved via TV and movies. Many stars of TV or film have theatre backgrounds, either in schooling or at the beginning of their career: Bruce Willis appeared (as a replacement) in the original Off-Broadway run of Fool For Love before he did Moonlighting or Die Hard; I saw Bronson Pinchot play George in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? while he was a Yale undergraduate (the Nick was David Hyde Pierce); Marcia Cross may have been a crazed denizen of Melrose Place and a Desperate Housewife, but she’s a Juilliard grad who did Shakespeare before achieving fame. But when Henry Winkler is announced in a new play, three decades after his signature television show ended, despite his Yale School of Drama education and prior stage work, all we hear is that “The Fonz” will be on Broadway.

The trope of “stars bringing their luster to the theatre” is insulting all around: it implies that the person under discussion is more celebrity than actor and it also suggests that there is insufficient radiance in theatre when no one in the cast has ever been featured in People or Us. By the same token, there’s media that won’t cover theatre at all unless there’s a name performer involved, so ingrained is celebrity culture, so theatre sometimes has to look to stars if it wishes to achieve any broad-based awareness. But the presence of stars on stage is nothing new, be it Broadway or summer stock; we may regret that theatre alone can rarely create a star, as it could 50 years ago, but we must get over that, because the ship has sailed.

There’s certainly a healthy skepticism when a star comes to the theatre with no stage background, and it’s not unwarranted. But I think that there are very few directors, artistic directors or producers who intentionally cast someone obviously unable to play a role solely to capitalize upon their familiarity or fame. In a commercial setting, casting Julia Roberts proved to be box office gold, even if she was somewhat overmatched by the material, but she was not a ludicrous choice; at the not-for-profit Roundabout, also on Broadway, Anne Heche proved herself a superb stage comedienne with Twentieth Century, following her very credible turn in Proof, before which her prior stage experience was in high school. Perhaps they might have tested the waters in smaller venues, but once they’re stars, its almost impossible to escape media glare no matter where they go.

The spikier members of the media also like to suggest, or declare, that when a famous actor works on stage after a long hiatus, or for the first time, it’s an attempt at career rehabilitation. This is yet another insult. Ask any actor, famous or not, and they can attest to theatre being hard work; ask a stage novice, well-known or otherwise, and they are almost reverent when they talk about the skill and stamina required to tell a story from beginning to end night after night after night. Theatre is work, and what success onstage can do is reestablish the public’s – and the press’s –recognition of fundamental talent. Judith Light may have become a household name from the sitcom Who’s The Boss, but it’s Wit, Lombardi and Other Desert Cities that have shown people how fearless and versatile she is. That’s not rehabilitation, it’s affirmation.

I should note that there’s a chicken-and-egg issue here: are producers putting stars in shows in order to get press attention, or is the media writing about stars because that’s who producers are putting in shows? There’s no doubt that famous names help a show’s sales, particularly the pre-sale, so in the commercial world, they’re a form of (not entirely reliable) insurance. And Broadway is, with a few exceptions, meant to achieve a profit. But it’s also worth noting that star casting, which most associate with Broadway, has a trickle down effect: in New York, we certainly see stars, often younger, hipper ones, in Off-Broadway gigs, and it’s not so unusual for big names to appear regionally as well, cast for their skills, but helping the theatres who cast them to draw more attention. Star casting is now embedded in theatre – which is all the more reason why it shouldn’t be treated as something remarkable, even as we may regret its encroachment upon the not-for-profit portion of the field. But they have tickets to sell too.

Look, it’s not as if any star needs me to defend them. The proof is ultimately found onstage; it is the run-up to those appearances that I find so condescending and snide. It shouldn’t be news that famous people might wish to work on stage, nor should any such appearance be viewed as crass commercialism unless it enters the realm of the absurd, say Lady Gaga as St. Joan. If stars get on stage, they should be judged for their work, and reviewed however positively or negatively as their performance may warrant.

I’m not naive enough to think attention won’t be paid to famous people who tread the boards, and I wish it needn’t come at the expense of work for the extraordinary talents who haven’t, for one reason or another, achieved comparable fame. I don’t need a star to lure me to a show, but I’m not your average audience member. Perhaps if the media didn’t kowtow to the cult of celebrity, if they realized how theatre is a launch pad for many, a homecoming for others, and a career for vastly more, theatre might be valued more as both a springboard for fame and a home for those with the special gift of performing live. So when the famous appear in the theatre, let’s try to forget their celebrity or stardom, stop trying to parse their motives, and try, if only for a few hours, to appreciate them solely, for good or ill, as actors.

April 12th, 2012 § § permalink

“I don’t care if I get paid at all. You don’t really do theater for money, it doesn’t make a lot of sense.” – John Malkovich

I’m inclined to give John Malkovich a pass on the statement above, as it was a response to a question about how much he was getting paid for a stage engagement. I’d also like to think that, since the statement was made at a press conference in Mexico, maybe there’s some bad translating involved. After all, Malkovich was an early member of the once scruffy and still ambitious Steppenwolf Theatre Company, so he’s paid his dues. As someone who alternates stage projects with art films (and the occasional Bruckheimer or Bay spectacle), he’s a star who hasn’t sold his soul to Hollywood, even if he has leveraged his name for such projects as a clothing line. But I have to take note of the quote, because it is emblematic of how theatre is discussed in relation to television and film, and makes theatre out to be something less than those fields, something that is done out of a mix of love and charity alone.

I would have been much happier if that statement was, “I don’t really do theatre for money now.” I wish all celebrities took that tack. Because by generalizing to all actors, they minimize the fact that actors need to make money to live, even if they work on stage out of love; it is only the independently wealthy or the highly successful actors who work in other fields who can do theatre indulgently. The fact is, for everyone working in, or trying to work in theatre, artist or administrator, theatre is a career choice, not a lark. Perhaps most recognize they’re unlikely to get rich, but we cannot (pardon the expression) afford to have it treated as a pastime. We need those who have succeeded to make the case for why it needs to be funded, for why people working in the theatre should be able to make a living at it if they choose, a living that can support them, a spouse or partner, a family; a career that provides health insurance, that allows for vacations, that doesn’t require a second job.

Does theatre pay like the movies or TV? No, it doesn’t (unless you’re Hugh Jackman or the authors of Wicked). But it can be a life, a fulfilling one. If every time a star takes to the stage they rhapsodize about love, and the press points out how extraordinary it is that they’re willing to take such a drastic pay cut to work on stage, the myth of theatre as avocation is perpetuated. Let’s also recognize that “no money” in theatre for celebrities is a relative term when they work commercially: they may not make as much as they do when working in those other fields, but trust me, we’d all be quite content with what I hear Ricky Martin is getting for appearing in Evita.

I have no doubt that when John Malkovich and the many celebrities spawned by or invited into Steppenwolf over the years return to that theatre, they make exactly what everyone else makes, and I applaud them for their commitment to that company and the many other theatres where they continue to work. That’s why I use the quote at the top of this piece as an object lesson, not a battering ram.

But let’s recognize it for hyperbole (I imagine if his fee were to go unpaid in Mexico, Malkovich’s agent or attorney would be getting on the phone right quick) and for unfortunate simplicity. Or perhaps everyone who can legitimately do so should immediately call his agent and offer him the greatest stage roles imaginable, the greatest directing projects he could desire. See what happens when you mention you’re asking him to donate his services.

September 20th, 2010 § § permalink

When I was a senior in college, I was sent to meet some relatively recent alumni of my school who had already begun to forge careers in the theatre. I remember the day quite vividly, and can still quote from it freely, even though of the two people with whom I met, one doesn’t recall it at all and the other remembers the meeting, but not the gist of the conversation.

At a distance of 26 years, one of the more salient bits of advice I received that day was as follows: “You know, if you’re any good at what you do, and you stay in this business long enough, you’re going to do just fine – because so many people drop out along the way.” Not exactly inspiring, but practical, grounded and, as I have learned, true.

Now I could easily spend a number of paragraphs parsing this advice and the factors that contribute to it, but I’ll leave that to you, because I’m more interested in a corollary to that advice, which I learned for myself: “If you stay in this business long enough, you’re going to meet your idols.”

Much is written, and said, no matter where you work in theatre, about “the theatrical community.” In my experience, the theatrical community is neither singular nor exceptionally small, though I daresay the number of people working in the professional theatre in the U.S. is probably smaller than the number of people working in the legal profession, or the medical profession, and it’s certainly dwarfed by any number of categories of public service employees.

But the fact is that theatre is small enough, fluid enough and interconnected enough that, over time, one builds up an enormous network of friends, associates and acquaintances, all of which Facebook, LinkedIn and the like would be all too happy to track and chart for you, were everyone you’ve ever encountered to subscribe to any one such service. I strongly suspect that in the field where John Guare popularized the notion of “six degrees of separation,” everyone in the theatre is likely separated by not more than three degrees.

Obviously the effect is intensified by a number of factors: how many theatres you work at or productions you work on, whether you move among different cities as you pursue your career, whether you change your area(s) of expertise as your career develops. In my case, I have had eight employers and five job titles, working in only three states; I have had some association with approximately 121 full professional productions, not counting workshops and readings.

But this is all prologue to the knowledge I declared above. And I will now launch into a seeming non-sequitur.

Last Saturday afternoon, I went to see a movie that, at that moment, was playing on precisely one screen in the country. In fact, I have this sneaking suspicion that it wasn’t even a movie, but a DVD projected onto a movie screen. It was a documentary about a once popular, now largely forgotten pop singer and songwriter named Harry Nilsson. I expected to be the only person there, and was heartened when I walked into the theatre to see three other people.

After settling down, I was aware of other people trickling in and settling as well, and of a couple who took their places in aisle seats across from me, just one row back. I didn’t not turn to look at them, but merely registered their presence, as one does. Then they began to speak to each other.

‘Wait a minute,’ I thought, when I heard a man’s voice. ‘That voice is awfully familiar.’ And so I turned and found myself perhaps five feet from Harold Prince. I immediately got up, took two steps, and politely interrupted, saying, “Hi, Hal.”

“Well look who’s here,” responded the legendary director and producer, who then introduced me to his wife Judy. He then asked why I was there, saying that they, too, had expected to be the only ones in the theatre. The chat continued, on various subjects, including a close mutual friend, until I excused myself just before the film was to begin.

I sat there in the half-light of the theatre, overjoyed. Because more concretely than ever before, I understood that Hal Prince knew who I was, remembered who I was, and was perfectly happy to have me accost him and start a conversation. All based primarily on his having done the American Theatre Wing’s podcast “Downstage Center” some two and a half years earlier – and his admission at that time that he watched our “Working in the Theatre” TV program, too. (“I have no idea when it’s on,” I recall him telling me. “My wife finds it.”)

Now I can imagine your thoughts as you read this. ‘He runs the American Theatre Wing. They do the Tony Awards. So he knows Hal Prince. Not a surprise.’

But what you don’t know is that, Sweeney Todd is my favorite musical of all time. It was by seeing the original production of Evita that I began to understand what a director actually does. A key factor that had influenced my decision to attend the University of Pennsylvania was that Hal had gone there, that at Penn I allied myself with the same theatre group he had once been a part of, and I worked on shows in the Harold Prince Theatre. When I was graduating, I wrote to him asking for a meeting, and though I never got a reply, my hero-worship was undiminished. On a trip to Las Vegas only weeks ago, I saw his revised version of Phantom. We even share the same birthday.

But, I hear you say, it’s not like this was your first meeting. No, it wasn’t. But it was the first time we’d merely run into each other, and he treated me as a familiar, a peer. There in Theatre 1 of Cinema Village, by sheer coincidence and a shared, obscure interest, I felt I had truly arrived, at the age of 48.

Yes, I have met many famous people. But knowing them is what’s important to me. I think that all of us who work in theatre are fans and no matter how long we do it, we remain fans. My frisson of excitement at running into Hal Prince last Saturday was a reminder of how much of a fan I still am, even though I needn’t stand at a stage door.

And for those thinking about their career, I can think of no better encouragement: “Do theatre. You’ll get to meet your idols.”

This post originally appeared on the American Theatre Wing website.

|

For those who haven’t been following them, a quick précis. West End Producer is, ostensibly, an individual on the production side of theatre in England, whose dishy asides about every aspect of the business always conclude with the simultaneously charming and condescending #dear. I have struck up a Twitter acquaintance with this person, we’ve shared a few jokes and they sent me a signed copy of their book. I’ve noticed their unwavering dedication to chronicling TV talent competitions as they air on weekend evenings (which can be bewildering, since the shows don’t play in the US) and just learned of a mutual passion for Sherlock, but this TV fixation doesn’t suggest someone at the country homes of those with bold faced names on the weekend. I’m newer to Actor Friend, whose full nom de tweet is Annoying Actor Friend, but the online persona is that of a snarky actor, seemingly more of a dedicated gypsy than an above-the-title star. While I won’t guess at gender (though WEP’s appearances in a latex mask disguise would indicate male, and in a book blurb, one writer suggests AF is female), I’d hazard that AF is in their 20s while WEP is likely 30ish (or more).

For those who haven’t been following them, a quick précis. West End Producer is, ostensibly, an individual on the production side of theatre in England, whose dishy asides about every aspect of the business always conclude with the simultaneously charming and condescending #dear. I have struck up a Twitter acquaintance with this person, we’ve shared a few jokes and they sent me a signed copy of their book. I’ve noticed their unwavering dedication to chronicling TV talent competitions as they air on weekend evenings (which can be bewildering, since the shows don’t play in the US) and just learned of a mutual passion for Sherlock, but this TV fixation doesn’t suggest someone at the country homes of those with bold faced names on the weekend. I’m newer to Actor Friend, whose full nom de tweet is Annoying Actor Friend, but the online persona is that of a snarky actor, seemingly more of a dedicated gypsy than an above-the-title star. While I won’t guess at gender (though WEP’s appearances in a latex mask disguise would indicate male, and in a book blurb, one writer suggests AF is female), I’d hazard that AF is in their 20s while WEP is likely 30ish (or more). Now you might imagine that an entire book of this arch tone would grow tiresome, let alone two, and I’d readily agree with you. That’s where both of these books turn out to be surprises. #SoBlessed, while the thinner of the pair, both literally and figuratively, pretty much drops all pretense of a character in one of its longer chapters, “On The Road,” which deals with touring. Offering a pointed critique of touring conditions and contracts, AF gets into some detail about the challenges of an actor’s life on tour. AF’s advocacy regarding compensation has taken on even greater urgency among some members of Actors Equity, with the full Twitter support and perhaps instigation of AF, has raised a stir about the pay structure of touring agreements over the holidays.

Now you might imagine that an entire book of this arch tone would grow tiresome, let alone two, and I’d readily agree with you. That’s where both of these books turn out to be surprises. #SoBlessed, while the thinner of the pair, both literally and figuratively, pretty much drops all pretense of a character in one of its longer chapters, “On The Road,” which deals with touring. Offering a pointed critique of touring conditions and contracts, AF gets into some detail about the challenges of an actor’s life on tour. AF’s advocacy regarding compensation has taken on even greater urgency among some members of Actors Equity, with the full Twitter support and perhaps instigation of AF, has raised a stir about the pay structure of touring agreements over the holidays.