February 4th, 2013 § § permalink

I had never seen the play before. I had wanted to, quite literally for decades, since its Broadway debut in the 1970s. But I never had the opportunity. I avoided the film version, because by all accounts, it didn’t work.

And so, when it was revived on Broadway a few seasons ago, I was thrilled. On the night I had tickets, I arrived at the theatre early, and sat waiting, expectantly. Then, as the lights dimmed, a phrase popped into my head.

“With one particular horse, called Nugget, he embraces.”

Moments later, Richard Griffiths came onstage and spoke those very same lines, the first words of Peter Shaffer’s Equus. How did they come to me? I am not clairvoyant.

As a teen, before I began going to the theatre regularly, I was an avid buyer of scripts, which I read over and over again. They were my introduction to theatre, and, unwittingly, I had committed bits of some to memory. I had not read Equus in some 25 years, yet the words were on my lips, unbidden.

In fact, this is not such a rare phenomenon in my life. I often find myself “singing along with plays,” moving my mouth at the theatre as if lip syncing. This happens when I encounter passages that I was required to learn by rote in high school English (“Friends, Romans, countrymen…”), but it also happens in the presence of many of the plays that fed my earliest interest in theatre.

My repertoire is highly eclectic, as is my collection of plays. Growing up just outside New Haven, I had access to a selection of used book stores, which were filled with the castoff texts of many a Yale Drama student. Brecht, Synge, Pinter, Moliere; Miller, Williams, O’Neill: I owned them all before going off to college. They remain on my shelves today (many with cover prices under $2). I’m not even sure which of them I know intimately, and which I’ve merely read.

Yes, of course, I sing along with Shakespeare; I imagine many do. Richard Thomas once told me that when he played Hamlet, he never worried about going up on his lines, since surely at least a half-dozen audience members could instantly prompt him on (he knew, however, that he was on his own if he dried while playing Peer Gynt, since no one knew that). The conclusion of A Midsummer Night’s Dream – “If we shadows have offended” – is a profound entreaty to me, and I cannot help but whisper along whenever it is spoken. It could, I think, be spoken at the curtain call of every play; it is the international anthem of theatre.

I find the same incantory power in George’s second act speech from Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, when he speaks of the young man ordering bergin and water to the amusement of surrounding gangsters. It is hypnotic and familiar, sad and funny, and speaks to the beauty of a play that most think of as entirely harrowing. I hope that I share nothing else with George, but I know that in some way, I share something with Edward Albee.

To be sure, repetition, whether in speech or reading, can enable one to recite familiar lines, but it goes much deeper for me. I often tear up when I recite or simply hear the Hebrew words of the Kaddish, be it in a synagogue or on TV, because while I have no comprehension of the language, the sound of it comforts and upsets me all at once, so imbued is it with the spirit of those I love who have died. But to make an absurd comparison, I am also moved, inspired, by the opening lines of the Star Trek TV series, which take me to my childhood before I discovered theatre – “To boldly go where no man has gone before” – and I say them aloud, quietly, whether they’re heard in film or in person, as I did last week when George Takei invoked them at the TEDx Broadway conference.

I am not suggesting that audiences should begin to commit passages of plays to memory so that they may join in when at the theatre; that would be as annoying as the patron who sings along with every song at a classic musical or the candy unwrapper who thinks that by going slowly, the noise is less apparent. But it does suggest that perhaps audiences might come to understand and appreciate plays on a deeper level if they had the opportunity to truly know snippets, so they could recognize them as old friends when they are spoken – and perhaps also begin to discern how different productions can reveal the words anew each time if those words are already deep within them.

Playwrights’ words are the fundamental reason I proselytize for the theatre. They live not just in books and on stage, but inside me. These are my text and my stories. They are my prayers.

January 28th, 2013 § § permalink

As I write late in the evening prior to the second TEDx Broadway conference, I find myself wondering how much the presentations tomorrow will focus on plays, which have become the poor stepchild of The Great White Way.

Over the summer, I wrote about Narrow Chances For New Broadway Musicals and considered Do Revivals Inhibit Broadway Musicals? I counted the most produced playwrights in recent years in The Broadway Scorecard: Two Decades of Drama and, responding to what I saw at a glance as some misguided copy in the promotion of tomorrow’s event, I spoke out strongly with the declaration False Equivalency: Broadway Is Not The American Theatre. Embedded in these posts were data, analysis — and my opinion — depicting Broadway as it is, not as some might perhaps wish it would be. As I noted in these posts, musicals dominate Broadway, both new and revivals, with roughly 80% of all Broadway grosses coming from musicals, even if the number of plays produced in most seasons outnumber new musical productions. Plays are admired, but when it comes to defining Broadway, the musicals by and large grab the lion’s share of money and attention.

That said, there’s one more, rather simple, data set that’s worth having in mind as tweets, blogs and news reports slice and dice tomorrow’s event (and I’ll be among those doing so). Here’s a listing of the Pulitzer Prizes for Drama and the Tony Award winners for Best Play, from 1984 to the present. I’m not suggesting that these awards are the final word on plays of quality, and awards success hardly guarantees box office success, but the two prizes provide a manageable universe for study. Why 1984? It’s an arbitrary choice, to be sure; it’s also the year I graduated college and went to work in the professional theatre, a microcosm of the celebrated plays of my theatrical career.

|

|

Pulitzer Prize |

|

Tony, Best Play |

| 2012 |

|

Water By The Spoonful |

|

Clybourne Park |

| 2011 |

|

Clybourne Park |

|

War Horse |

| 2010 |

|

Next To Normal |

|

Red |

| 2009 |

|

Ruined |

|

God Of Carnage |

| 2008 |

|

August: Osage County |

|

August: Osage County |

| 2007 |

|

Rabbit Hole |

|

The Coast Of Utopia |

| 2006 |

|

no award |

|

The History Boys |

| 2005 |

|

Doubt |

|

Doubt |

| 2004 |

|

I Am My Own Wife |

|

I Am My Own Wife |

| 2003 |

|

Anna in the Tropics |

|

Take Me Out |

| 2002 |

|

Topdog/Underdog |

|

The Goat, Or Who Is Sylvia |

| 2001 |

|

Proof |

|

Proof |

| 2000 |

|

Dinner With Friends |

|

Copenhagen |

| 1999 |

|

Wit |

|

Side Man |

| 1998 |

|

How I Learned To Drive |

|

Art |

| 1997 |

|

no award |

|

The Last Night Of Ballyhoo |

| 1996 |

|

Rent |

|

Master Class |

| 1995 |

|

The Young Man From Atlanta |

|

Love! Valour! Compassion! |

| 1994 |

|

Three Tall Women |

|

Angels In America: Perestroika |

| 1993 |

|

Angels In America: MA |

|

Angels In America: MA |

| 1992 |

|

The Kentucky Cycle |

|

Dancing At Lughnasa |

| 1991 |

|

Lost in Yonkers |

|

Lost in Yonkers |

| 1990 |

|

The Piano Lesson |

|

The Grapes Of Wrath |

| 1989 |

|

The Heidi Chronicles |

|

The Heidi Chronicles |

| 1988 |

|

Driving Miss Daisy |

|

M. Butterfly |

| 1987 |

|

Fences |

|

Fences |

| 1986 |

|

no award |

|

I’m Not Rappaport |

| 1985 |

|

Sunday In The Park With George |

Biloxi Blues |

| 1984 |

|

Glengarry Glen Ross |

|

The Real Thing |

The honored plays above, shorn of duplicates as well as the years the Pulitzers honored musicals, make up a total of 43 different works that were recognized for achievements in playwriting in 29 years. Only nine works appear on both lists and The Pulitzers are only for American plays, which helps to reduce duplication.

Now here’s the key question: how many of those works actually had their world premieres on Broadway? The answer: only five. Those plays were Rabbit Hole, Lost In Yonkers, The Goat, The Last Night Of Ballyhoo and M. Butterfly. The others all began in not for profit U.S. venues, as close as Off-Broadway or as far as Seattle, or in subsidized or commercial venues in Ireland, England, and Europe. That’s not to say that there weren’t worthy plays that weren’t recognized which may have been produced directly on Broadway, but the ones that reaped the conventionally accepted big awards didn’t begin there. In the Pulitzer list, there are many that never played Broadway, at least in their original incarnations, as I discussed in At Long Last Broadway.

So as the future of Broadway is a subject on many minds in the next 24 to 36 hours, it’s worth remembering that strikingly few new plays debut there, as they commonly did in the days before the resident theatre movement really bloomed. If plays are to make their marks in Broadway history under the existing models of production, they need to be discovered, birthed and nourished elsewhere. National and international recognition may still be New York-centric, but the most honored works start overwhelmingly just about everywhere other than Broadway. Could that ever change? Should it? And if the answer is yes, then how?

December 23rd, 2012 § § permalink

Those who follow my Twitter feed know that I almost never tweet out reviews; I figure that there are plenty of others, including critics themselves, who do, so why be redundant. I focus my energies on highlighting material which may not have had the same kind of exposure.

Those who follow my Twitter feed know that I almost never tweet out reviews; I figure that there are plenty of others, including critics themselves, who do, so why be redundant. I focus my energies on highlighting material which may not have had the same kind of exposure.

For the second year in a row, I’m breaking that moratorium on my blog, because “Best Of” and “Top Ten” lists are affirmative summaries of the year in theatre. They represent what critics found most compelling or enjoyable, and even though some decide to toss brickbats with “Worst Of” lists, I’ve avoided linking to those unless they’re appended directly to the “Best Of” praise.

It’s worth noting that all of these lists should be taken with a grain of salt; that is to say, except in all but the smallest markets, they are almost inevitably incomplete, as critics do not have the time (or are not compensated) to see every last production in the area. These are perhaps better considered “favorites,” but that is no doubt insufficiently declarative for many editors, and if 10 Commandments could be selected out of a pool of 617, then surely critics can do likewise. But it’s worth noting that the critic for Time, a national magazine, has restricted his selection to New York; is this because that is where he saw the best work, or because that is the only city in which he went to the theatre this year?

Other than scanning my most cursory summary of each list, I urge you to use the links to look more carefully at what critics had to say about the works they selected, and in particular to do so to learn more about those plays that are unfamiliar to you. Also, as there were multiple Uncle Vanyas, for example, it may not be clear which production is being praised.

Finally, I should say that this is a work in progress and inevitably incomplete, but I urge you to tweet to me at @hesherman with links to lists that don’t appear here, and I’ll keep updating until after the new year.

* * *

America: Terry Teachout, The Wall Street Journal

St. Joan, A Little Night Music, Nobody Loves You; also a number of other notable productions and artists.

Atlanta: Wendell Brock, Atlanta Journal Constitution

Clyde ‘n Bonnie: A Folktale, Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner?, Apples And Oranges, Next To Normal, Wolves.

Baltimore: multiple critics, City Paper

The Iceman Cometh, The Whipping Man, The Brothers Size, Into The Woods, Office Ladies, Breaking The Code, This Bird’s Flown: A Tragedy Of Antiquity, A Skull In Connemara, Drunk Enough To Say I Love You, Ages Of Man.

Berkshire County MA: Jeffrey Borak, The Berkshire Eagle

A Chorus Line, Parasite Drag, Tryst, Tomorrow The Battle, Far From Heaven, A Gentleman’s Guide To Love And Murder, Cassandra Speaks, Edith, Pride @ Prejudice, Dr. Ruth All The Way.

Boston: Carolyn Clay, The Phoenix

Red, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Avenue Q, Billy Elliott, Master Harold…and the boys, The Elaborate Entrance Of Chad Deity, Marie Antoinette, Ted Hughes’ Tales From Ovid, Betrayal, Our Town.

California: Lisa Millegan Renner, The Modesto Bee

Time Stands Still, The Grapes of Wrath, Carousel, Metamorphoses, Brighton Beach Memoirs, Three Days Of Rain, Gypsy, The Shape Of Things, The Mikado, Mamma Mia!.

Cleveland: Andrea Simakis, Cleveland Plain Dealer

The Whipping Man, Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, Anything Goes, Bust, Avenue Q, The Mousetrap, In The Next Room, The Secret Social, The Texas Chainsaw Musical!.

Chicago: Catey Sullivan, Chicago Magazine

Angels In America, Cascabel, Dark Play, The Doyle And Debbie Show, Hamlet, Hit The Wall, The Iceman Cometh, Jitney, A Little Night Music, Sunday In The Park With George.

Chicago: Bob Bullen, Chicago Theatre Addict

Camino Real, Angels In America, Immediate Family, Superior Donuts, The Light In The Piazza, A Little Night Music, Eastland, Hit The Wall, Good People, Sunday In The Park With George.

Chicago: Chris Jones, Chicago Tribune

Sunday In The Park With George, Good People, The Iceman Cometh, Hit The Wall, Metamorphoses, Les Misérables, Time Stands Still, The Invisible Man, The Light In The Piazza, A Little Night Music; also Annie, Beauty And The Beast, Death And Harry Houdini, Kinky Boots, The Letters, The Mikado, Moment, Oedipus El Rey, Sweet Bird Of Youth, When The Rain Stops Falling.

Chicago: Kris Vire, Time Out Chicago

Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, Good People, Hit The Wall, The Iceman Cometh, Idomeneus, Invisible Man, Metamorphoses, Oedipus El Rey, Romeo Juliet, Sunday In The Park With George.

Columbus: David Ades, The Other Paper

Age Of Bees, Long Way Home, King Lear, The Irish Curse, La Boheme, Memphis.

Dallas: Elaine Liner, Dallas Observer

Essay, “The Year in Dallas Theatre.”

Dallas: Arnold Wayne Jones, Dallas Voice

Ruth, The Most Happy Fella, The Night Of The Iguana, The Elaborate Entrance Of Chad Deity, The Farnsworth Invention, Becky Shaw, Oklahoma!, The Producers, Superior Donuts, On The Eve.

Halifax, Nova Scotia: Kate Watson, The Coast

Lysistrata Temptress Of The South, Titus Andronicus, Hawk, Twelve Angry Men, Arsenic And Old Lace, The Drowsy Chaperone, Inherit The Wind, Same Time Next Year, Pageant, Bone Boy, Bare, Whale Riding Weather, The Monument, The Men, Who Killed Me, Kill Shakespeare.

Hartford: Frank Rizzo, The Hartford Courant

The Realistic Joneses, A Gentleman’s Guide To Love And Murder, Marie Antoinette, Into The Woods, Carousel, A Raisin In The Sun, Sty Of The Blind Pig, A Winter’s Tale, Les Misérables; also, Satchmo At The Waldorf, The Tempest, Bell Book & Candle, Metamorphosis, Harbor, I’ll Fly Away.

Kansas City: Robert Trussell, Kansas City Star

The Kentucky Cycle, Titus Andronicus, The Whipping Man, The Mystery Of Irma Vep, Time Stands Still, The Motherfucker With The Hat, Antony And Cleopatra, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Moustrap, The Real Inspector Hound, Inspecting Carol, The Importance Of Being Earnest, Making God Laugh, Game Show, Hairspray, Lucky Duck, Spring Awakening, Shrek, The Seagull, Sex Drugs Rock & Roll, The Addams Family, Memphis, An Eveneing With Patti LuPone & Mandy Patinkin, Next To Normal, Master Class, The Fantasticks.

Las Vegas: staff writers, Las Vegas Weekly

Nurture, Measure For Pleasure, Crazy For You, Golda’s Balcony.

Lehigh Valley, PA: Myra Yellin Outwater, The Morning Call

On The Town, I Love A Piano, Anything Goes, Thoroughly Modern Millie, Doubt, Arsenic and Old Lace, A View From The Bridge, The Tempest, Eleanor Handley in Much Ado About Nothing & Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, Parfumerie, The Miracle of Christmas.

London, Matt Wolf, The Arts Desk

Brimstone And Treacle, Cornelius, A Doll’s House, The Effect, In The Republic Of Happiness, Julius Caesar, Merrily We Roll Along, The River, Sweeney Todd, The Taming Of The Shrew.

London, multiple critics, The Guardian

Ten Billion, You Me Bum Bum Train, Gatz, Ganesh Versus The Third Reich, Noises Off, Mies Julie, Three Kingdoms, Three Sisters, Posh, In Basildon.

London: Susannah Clapp, The Observer

The Boys Of Foley Street, Coriolan/us, Love And Information, Timon Of Athens, Sea Odyssey, Constellations, The Curious Incident Of The Dog In The Night-Time, Red Velvet, Julius Caesar (x2).

Los Angeles and New York: Charles McNulty, Los Angeles Times

Clybourne Park, Death Of A Salesman, Follies, In The Red And Brown Water, Ivanov, Jitney, Krapp’s Last Tape, Our Town, Waiting For Godot, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?.

Miami: John Thomason, Miami New Times

Winter and Happy, Becky’s New Car, The Turn Of The Screw, A Man Puts On A Play, Venus IN Fur, I Am My Own Wife, The Motherfucker With The Hat, Death And Harry Houdini, Next To Normal, Ruined.

Milwaukee: Mike Fischer, Journal Sentinel

Musicals: Avenue Q, Big, Blues In The Night, A Cudahy Caroler Christmas, Daddy Long Legs, The Sound Of Music, Sunday In The Park With George, Tick Tick…BOOM, Victory Farm, West Side Story; Plays: A Thousand Words, Cartoon, The Chosen, Honour, Love Stories, Microcrisis, Othello, Richard III, Skylight, To Kill A Mockingbird.

Minneapolis: Rohan Preston and Graydon Royce, Star Tribune

- Rohan Preston: Untitled Feminist Show, The Brothers Size, Are You Now Or Have You Ever Been, Dirtday!, Buzzer, In The Next Room, Swimming With My Mother, The Origin(s) Project, A Behanding In Spokane, Fela!

- Graydon Royce: Flesh And The Desert, Ragtime, Spring Awakening, Sea Marks, Compleat Female Stage Beauty, Cherry Orchard, Waiting For Good, Measure For Measure, In The Next Room, Buzzer

New Jersey: Bill Canacci, Courier Post

Once, Falling, The Piano Lesson, The Whale, Tribes, End Of The Rainbow, The Best Man, Clybourne Park, Merrily We Roll Along, Forbidden Broadway: Alive And Kicking.

New Jersey: Ronni Reich, Newark Star Ledger

Dog Days, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, Death Of A Salesman, The Convert, Henry V, The Mystery Of Edwin Drood, The Best Of Enemies, Once, No Place To Go.

New York: Matt Windman, AM New York

Once, Merrily We Roll Along, The Mystery Of Edwin Drood, Clybourne Park, Closer Than Ever, Forbidden Broadway: Alive And Kicking, Vanya & Sonia & Masha & Spike, Porgy And Bess, Harvey, Bring It On.

New York: Mark Kennedy, Associated Press

Top 10 Theatre Moments: Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, Once, Clybourne Park, James Corden, Neil Patrick Harris, Kevin Spacey as Richard III, If There Is I Haven’t Found It Yet, the death of Marvin Hamlisch, A Christmas Story: The Musical, the return of Forbidden Broadway.

New York: Robert Feldberg, The Bergen Record

Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, One Man Two Guvnors, Once, Annie, The Mystery Of Edwin Drood, The Best Man, Wit, Grace.

New York, Jeremy Gerard, Bloomberg News

Death Of A Salesman, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, Disgraced, Sorry, February House, Slowgirl, Uncle Vanya (x 2), the Fugard season, One Man Two Guvnors, Detroit; also The Lady From Dubuque, Annie, Vaya & Sonia & Masha & Spike, A Streetcar Named Desire, Newsies, If There Is I Haven’t Found It Yet.

New York, Thom Geier, Entertainment Weekly

Once, The Heiress, Porgy And Bess, Rapture Blister Burn, Newsies, Tribes, Death Of A Salesman, One Man Two Guvnors, Giant, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?.

New York: David Rooney, The Hollywood Reporter

As You Like It, Clybourne Park, Death Of A Salesman, Disgraced, 4000 Miles, Porgy And Bess, Golden Boy, One Man Two Guvnors, The Piano Lesson, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?.

New York: T. Michelle Murphy, Metro

Venus In Fur, Once, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, Death Of A Salesman, Then She Fell, Triassic Parq, Bare: The Musical, Peter And The Starcatcher, As You Like It, Helen And Edgar.

New York: Joe Dziemanowicz, New York Daily News

20 stage moments to remember: Assistance, Bad Jews, Claire Tow Theatre, Clybourne Park, Delacorte Theatres 50th, Einstein On The Beach, Feinstein’s, 54 Below, Marvin Hamlisch, Newsies, Nina Arianda, Norbert Leo Butz, Once, One Man Two Guvnors, The Piano Lesson, Rebecca, Sorry, Uncle Vanya, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, Yvonne Strahovski.

New York, Elisabeth Vincentelli, New York Post

Assistance, Detroit, Gob Squad’s Kitchen, Natasha Pieere and The Great Comet Of 1812, One Man Two Guvnors, 3C, Tribes, Uncle Vanya, We Are Proud To Present A Presentation…, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?.

New York: John Lahr, The New Yorker

Golden Boy, Death Of A Salesman, Peter And The Starcatcher, Title And Deed, Timon Of Athens, Tribes, Richard III, Clybourne Park, The Whale, The Piano Lesson.

New York, Scott Brown, New York magazine

Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, Tribes, Sorry, Death Of A Salesman, Cock, the black box conjurations, Detroit, Uncle Vanya, the unmusicals, One Man Two Guvnors.

New York, Ben Brantley and Charles Isherwood, The New York Times

- Ben Brantley: Cock, Harper Regan, Mies Julie, Neutral Hero, Once, One Man Two Guvnors, Peter And The Starcatcher, Sorry, Then She Fell, Uncle Vanya.

- Charles Isherwood: Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, Detroit, The Piano Lesson, Title And Deed/The Realistic Joneses, The Iceman Cometh, A Gentleman’s Guide To Love And Murder, Golden Boy, Disgraced, Uncle Vanya, One Man Two Guvnors.

New York: Jesse Oxfeld, The New York Observer

Death Of A Salesman, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Wolff?, 4000 Miles, Clybourne Park, Hurt Village, Detroit, The Whale, Disgraced, Vanya & Sonia & Masha & Spike, Cock, The Twenty-Seventh Man, A Civil War Christmas, Assistance, The Great God Pan, The Bog Meal, Rapture Blister Burn.

New York: Richard Zoglin, Time magazine

Annie, Detroit, One Man Two Guvnors, A Christmas Story: The Musical, Grace, Louis CK on tour, End Of The Rainbow, Forbidden Broadway: Alive And Kicking, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf, 4000 Miles.

New York: David Cote and Adam Feldman, Time Out New York

- David Cote: Golden Boy, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf, Death Of A Salesman, One Man Two Guvnors, Uncle Vanya, Glengarry Glen Ross, Detroit, Natasha, Pierre And The Great Comet of 1812, A Map Of Virtue, If The Is I Haven’t Found It Yet.

- Adam Feldman: Natasha, Pierre And The Great Comet Of 1812, The Piano Lesson, Tribes, Golden Boy, The Material World, A Map Of Virtue, Hurt Village, The Twenty-Seventh Man, 3C.

Orange County CA: Paul Hodgins, Orange County Register

Topdog/Underdog, Car Plays, Elemeno Pea, The Jacksonian, Sight Unseen, American Idiot, Sight Unseen, Waiting For Godot, Jitney, War Horse, Red, The Book Of Mormon, Krapp’s Last Tape, Other Desert Cities.

Philadelphia: J. Cooper Robb, Philadelphia Weekly

Body Awareness, Spring Awakening, The Music Man, Clybourne Park, The Liar, Slip/Shot, The Marvelous Wonderettes, Next To Normal, A Behanding In Spokane, The Scottsboro Boys.

Portland ME: Megan Grumbling, The Portland Pheonix

Aquitania, The Birthday Party, Doctor Faustus Lights The Lights, Eurydice, Faith Healer, Ghosts, Henry IV.

Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill, North Carolina: multiple staff, Indy Week

Original Scripts & Adaptations: What Every Girl Should Know, Jude The Obscure, Shape, Children IN The Dark, Donald, From F To M To Octopus, Sketches Of A Man, Perfect, I Love My Hair When It’s Good: And Then Again When It Looks Defiant and Impressive, The Men In Me; Productions: Acts of Witness: Blood Knot, The Brothers Size, Donald, �I Love My Hair When It’s Good: And Then Again When It Looks Defiant and Impressive, Let Them Be Heard, New Music: August Snow, Night Dance, Better Days, The Paper Hat Game, Penelope, Radio Golf, Red, Richie, What Every Girl Should Know.

San Antonio: Deborah Martin and Michael E. Barrett, San Antonio Express-News

August: Osage County, Superior Donuts, Killer Joe, King Lear, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, íCarpa, Open Sesame, Firebugs, A View From The Bridge, Macbeth, God Of Carnage, I-DJ, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, Les Misérables, An Adult Evening Of Shel Silverstein, Hello Dolly!, My Fair Lady, American Buffalo.

San Diego: David L. Coddon, San Diego City Beat

Blood And Gifts, Allegiance, Kita Y Fernanda, A Raisin In The Sun, Harmony Kansas, The Scottsboro Boys, The Car Plays, Parade, Topdog/Underdog, Zoot Suit; also, Visiting Mr. Green, American Night: The Ballad Of Juan Jose, Fiddler On The Roof, Good of Carnage, Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots.

San Jose: Karen D’Souza, The Mercury News

Becky Shaw, Humor Abuse, The Aliens, The Caretaker, Any Given Day, War Horse, An Iliad, The White Snake, Woyzeck.

St Louis: Dennis Brown and Paul Friswold, Riverfront Times

Sunday In The Park With George, No Child…, Angels In America, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Sweeney Todd, Thoroughly Modern Millie, The Complete Works Of William Shakespeare (abridged), The Children’s Hour, Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, Eleemosynary, This Wide Night, The Foreigner.

Toronto: J. Kelly Nestruck, Globe And Mail

Top 10 Shows (via personal blog): Maybe If You Choreograph Me You’ll Feel Better, The Iceman Cometh, The Matchmaker, Terminus, Home, An Enemy Of The People, The Golden Dragon, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, War Horse, Enron; also Top 10 Theatre Picks.

Toronto: Jon Kaplan and Glenn Sumi, Now Toronto

Terminus, Proud, The Little Years, Caroline or Change, Kim’s Convenience, The Small Room At The Top Of The Stairs, Miss Caledonia, War Horse, The Penelopiad, Tear The Curtain.

Toronto: Toronto Star

Actress Maev Beatty, War Horse, opera as theatre, Cymbeline, The Small Room At The Top Of The Stairs.

Washington DC: Peter Marks, The Washington Post

Mr Burns a Post-Electric Play, Astro Boy And The God Of Comics, Beertown, Really Really, The Strange Undoing Of Prudencia Hart, The Normal Heart, haute puppetry, locally grown theatre, The Servant Of Two Masters, fine old musicals.

as of 12/30/12 11:00 am

December 18th, 2012 § § permalink

The holodeck: a future threat to theatre, or just another contender that will fall by the wayside?

I have said one more than one occasion, only half in jest, that until the holodeck, as portrayed on the later Star Trek series, is perfected, theatre’s unique live aspects will sustain it through challenges. Now I’m growing less worried about even the holodeck because, if the current pace of technology holds true, continual upgrades will be constantly rendering that still-imaginary invention obsolete.

I’m prompted to this musing by a recent article from The Atlantic, which chronicles the challenges faced by vintage, though not necessarily classic, movies. In a medium a bit more than 100 years old, the pace of technology may well serve to make it impossible for some older films to ever be seen again. The conversion to digital projection eliminates access to 35 mm projectors, and the economics of conversion from film to digital means that only films deemed most worthwhile will make that leap. We’ve gone from worrying about early silver nitrate films going up in flames to being unable to view movies on stable stock in a relatively few years. And just as the Edison cylinder gave way to the acetate (and later vinyl) record, which in turn fell to the CD which has now been supplanted by the mp3, progress may well leave a significant portion of film history abandoned in its wake.

The new impending crisis in film preservation worries me, because while I have made my career in theatre, I am an avid filmgoer. Indeed, I am a movie Luddite to many, because I do my best to see any film I’ve not seen before in a theatre, not on my 42 inch flat-screen with home theatre sound. Movies (we’re really going to have to stop calling them films in a film-less era) are, or at least were, made to be shown at a grand scale, and watching them in my living room diminishes the experience.

At the same time, the movie conundrum reinforces my unwavering belief that theatre will survive perpetual technological advances. Even though new innovations may well have their own opportunities for wonder (elements of science fiction films from my childhood are now everyday items), the theatre benefits – as does music, dance, and other live performing arts – from the fact that any electronic duplication diminishes the experience. While we can make a record of what happened on a stage, watching it on a screen, even in the finest 3-D imaginable, inevitably distances the viewer from the immediacy of “being there.” When we watch an image, we do not share space with it; our responses cannot influence it in the slightest.

Even when stories were passed from generation to generation orally, and certainly from the time they began to be written down, theatre set an important artistic pattern that is unchanged today. The initial act of creating for the theatre, the invention of the text, was rooted in the establishment of a template, a script, rather than the crafting of a competed object, be it cave painting or sculpture or movie. Even though an artist such as Sol LeWitt created “kits” that would allow for the replication of his work without his direct involvement, they were exacting; museums replicating LeWitt works still were required to obtain his approval.

Because of the practice of script (and score) as template, to which actors, directors, designs are added in ever-changing sets of interpreters, there is nothing fixed but the roadmap. Efforts to dictate a singular, “proper” way to mount a play or musical usually prove detrimental; prior magic cannot be recaptured – even within long-running shows, carefully maintained, there are shifts in style and emphasis; we saw the life return to Gilbert & Sullivan’s works only when they were loosed from the stifling museum of the D’Oyly Carte straitjacket. Even the strictest of authors’ estates, seeking to preserve what they believe to be the original “intent,” can’t entirely quash new visions; theatre’s most importantly innovations aren’t technological, they’re human, each and every time. And even though theatre’s human element may prevent it from being “cost-effective,” there will always be those willing to pay for the live event (though our challenge is to keep it accessible for more than just the wealthy).

As with movies, we tend to be most familiar with the “greatest hits,” the works that have proven most popular or respected over time. But for at least the past few hundred years, even when they go unproduced, plays aren’t necessarily lost forever; they’re just hidden on some back shelf, gathering dust, awaiting rediscovery. They won’t disintegrate, or become utterly inaccessible, or be maintained in some diminished or altered form, as many films likely will be. A theatre script will just wait, patiently, for some group of people to pick it up and breathe life into it once again.

December 5th, 2012 § § permalink

In the past five Broadway seasons, there have been seven productions of plays by David Mamet, making him in all likelihood the single most produced playwright on Broadway in that period, and certainly the most produced living playwright. That’s a pretty remarkable achievement, especially when you consider that Mamet has only had 15 Broadway productions in his career. Three of those 15 were American Buffalo productions, while another three were Glengarry Glen Ross.

Patti LuPone and Debra Winger in “The Anarchist”

But the impending closing of his newest play, The Anarchist, only two weeks after its opening, gives Mamet another record: this marks the third Broadway season in which there have been two Mamet productions on Broadway, with one in each pair closing prematurely. For the record: the autumn of 2008 saw both Speed-the-Plow and American Buffalo (the latter closing in a week, while the former saw three lead actors in a single role, though it completed its limited run); 2009 paired Oleanna and Race (the revival lasting less than two months, while the new play enjoyed a sustained run); and now we have The Anarchist closing while Glengarry Glen Ross is selling well during a limited run comprised equally of previews and regular performances.

Critical reaction certainly hastened the demise of the fast closers, but shows – especially those with stars, as has been the case with all recent Mamet productions – can manage to outpace critical opinion. But stars haven’t been infallible insurance with Mamet; a production of A Life in the Theatre, with the estimable Patrick Stewart and TV star T.R. Knight was seen briefly in 2010, the sole Mamet entry that season.

Cedric the Entertainer, Haley Joel Osment & John Leguizamo in “American Buffalo”

We can argue the merits of David Mamet as a playwright, or the quality of the various productions, but this spate of openings (and closings) certainly suggests that Mr. Mamet has imposed on our hospitality a bit longer than might be advisable. When the typical Broadway season only sees 40 new productions a year, two a season from the same playwright is not an insignificant amount – and in the case of Glengarry, it has only been seven years since the last production.

It may well be that Mamet is overexposed, and familiarity is breeding contempt in some quarters. What’s unfortunate in this spate of commercial programming is that some of Mamet’s less produced work – say the nihilistic Edmond or the ribald Sexual Perversity in Chicago, neither ever seen on Broadway – have yet to surface in major New York revivals, and as someone who has never been fortunate enough to see either on stage, I’d welcome them.

Aaron Eckhart and Julia Stiles in “Oleanna”

When Edward Albee’s stock rose after a season at Signature Theatre and the Vineyard production of Three Tall Women in the mid-90s, it triggered a wave of Albee revivals, mixed with new work, on Broadway and Off, allowing a new generation to see virtually every major work by our most esteemed living playwright, after a period of disfavor. There’s nothing wrong with David Mamet getting the same treatment (though he never experienced the fallow period that Albee did in the 80s), and I even delight in the idea that such a retrospective can take place in the commercial arena. But the Albee “festival” was spread out over some 19 years by the time we got to The Lady From Dubuque (and we’re unlikely to ever see The Man Who Had Three Arms).

Maybe our Mamet feast likewise needs a bit more time to digest between courses, so that we might be inclined to savor them more when they come. Speaking with a marketing and sales agenda, rather than an aesthetic one, I must haul out a cliché: absence, as they say, does make the heart grow fonder.

November 7th, 2012 § § permalink

“Time, time, time, see what’s become of me.” – Paul Simon, “Hazy Shade of Winter”

Life, god willing, is long. Plays are short.

Though perhaps we don’t think about it often, it bears remembering that plays and musicals, which can encompass so much, usually run about two to two-and-a-half hours (including intermission). Three hours is long; Gatz is a marathon.

In the time allowed for them, or permitted by the author, they can be a slice of real time or a span of years; a single location or spots around the world (and beyond); we see stories told in chronological order, backwards, or even all mixed up (see Ayckbourn, Pinter and Priestley). But compared to the lives of people, any individual piece of theatre is brief.

Theatre has proven fairly unconducive to stories told in multiple parts (like serialized TV) or as sequels (as in film). That’s not to see there aren’t assorted plays and cycles that have expanded beyond the usual time parameters of a single play, but they’re the exception, and, when fully assembled, they are greeted as special events, and usually have short theatrical lives due to the expanse and expense of producing them.

The Apple Family as seen in 2011 in Richard Nelson’s”Sweet and Sad”

This rarity is why I find the “Apple Family Plays” by Richard Nelson, as produced at The Public Theater, so compelling as a theatrical experience – because they are playing out the lives of their characters in snapshots of real time over a period of years. When I went to see That Hopey-Changey Thing in 2010, I think I was drawn by the novelty of a play set precisely when its theatrical run was happening; it was set on Election Day of that year and ran in the days just before and just after that night, officially opening on the day it was set. In 2011, when Nelson’s Sweet and Sad revisited the family on the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, the novelty meant less than the audacity of the playwright’s effort: same cast, same characters, in the same room, almost a year later. As I have written previously, I found the experience of the second play deeply moving.

Last night, I attended the opening of the third play in the planned quartet, Sorry, and I had yet a new response. I was genuinely delighted to see these characters again. They were people I knew, they had invited me as a silent guest to another gathering of the clan; I was a prodigal returning home, dutifully, so to speak. Deeply concerned about the presidential election, I preferred to share the evening in their company than with anyone else. Even though there were moments of sadness and tension, I think I sat with a smile on my face for perhaps the first 30 minutes (it’s hard to say, as the two hour running time flew by). I was just so darned happy to see these people.

The Apples had not worn out their welcome, as television characters can do with 22 episodes a year; I got fed up with Greg House, I don’t care who Ted Mosby marries, I don’t even know who’s threatening or sleeping with Sookie these days. Perhaps that’s why some of my favorite TV series have been so short: the obnoxiousness of Cumberbatch’s Sherlock doesn’t overstay, the New Burbage Theatre of Slings and Arrows won’t offer me another take on Hamlet; the first season of The Sopranos was perfect, while the subsequent seasons meandered, dissipating my awe.

In film, like theatre, most stories are told in the two-hour span that perhaps has evolved to match bladder capacity. The stories that go on are epics, or the so-called tentpole series (Bond, the Marvel heroes, hobbits, Luke Skywalker, Indy), and while I enjoy them, I don’t invest emotionally as I do in most self-contained stories. I will confess to one exception: as a childhood sci-fi geek, the death of Spock in Star Trek II was quite upsetting, precisely because I have lived with this character on TV (both live and animated), as well as in books, for many years.

While it was the “this is taking place right now” aspect of the Apple Family plays that first caught my attention, it is the span of time between them that has proven most captivating. They have become the theatrical equivalent of the British documentary series 7 Up, 14 Up, 21 Up and so on. We dip into the Apples’ lives over years, not hours; that is the verisimilitude that lifts them beyond their individual or collective worth as plays. They track our lives as we track theirs.

Inevitably, with a cycle of plays like this one, there is a desire in the audience and an urge among the creative tem (I imagine) to one day see them all in a single weekend. I am normally a fan of this kind of theatre: The Norman Conquests, The Orphans Home Cycle, The Coast of Utopia all become greater theatrical events when seen in a single day. Yet I now think that to do so with the Apple plays would not have the impact of their current method of production.

Yes, we would marvel at the skill and stamina of the cast and we would make more connections between the plays if they were performed in rapid succession. But we wouldn’t benefit from the incremental changes in the actors bodies, their voices, their faces as they age with us from year to year; on a single day or weekend, we wouldn’t have the joy of returning to old friends after true time away, merely the expectation of the next play after a meal break.

Don’t get me wrong – I want to see these plays produced, widely, in the years to come, under whatever schedule necessary. Time itself will alter them, as they become fixed at moments in the past, instead of playing as current, and practicality may dictate that the same cast won’t be available year after year in other venues. One actor was absent from this third play because of another professional commitment; his character will be forever absent from Sorry because of this.

The Apple Family Plays are a unique temporal experience in the theatre, and I treasure them deeply precisely because they use time and the outside world as no other show(s) I’ve seen ever has. I wish that Nelson would write the story of the Apples for many years to come, and that his original company would enact it far beyond the planned fourth play. I would plan my life around sharing in theirs.

But in the meantime, I look forward to seeing them next year for Thanksgiving, god willing.

November 1st, 2012 § § permalink

Sanjay at Froghammer must be so proud. You remember Froghammer, the firm brought in by the New Burbage Festival to shake up its advertising and audiences, to cast off their stodgy image. So bold, so vibrant. Oh yes, and (spoiler alert) in that scenario, a fraud.

Sanjay at Froghammer must be so proud. You remember Froghammer, the firm brought in by the New Burbage Festival to shake up its advertising and audiences, to cast off their stodgy image. So bold, so vibrant. Oh yes, and (spoiler alert) in that scenario, a fraud.

It’s hard not to recall this fictional scenario, from the ever-brilliant Canadian TV series Slings and Arrows, as the venerable Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Canada drops the middle word from its name…again, having jettisoned it in the 1970s and restored it in 2007. In the words of Stratford’s new artistic director Antoni Cimolino, who assumed his new post officially today, the name “is simple and direct, it resonates with people and it carries our legacy of quality and success.” It also eradicates the name of Shakespeare in the general promotion of the festival. How that plays out on its stages, and its materials, will be seen in the seasons to come.

Stratford is hardly the first theatre to diminish The Bard’s name. Joseph Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival began to transition as its Lafayette Street home became prominent and rose to co-billing in the portmanteau Joseph Papp’s The Public Theater/New York Shakespeare Festival, which later gave way simply to The Public Theater (which still produces Shakespeare in the Park, a catch-all that has included Comden & Green and Bernstein, Sondheim, and Ragni, Rado & McDermott in more recent summers).

Even the American Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut, as it drew its last breaths in the late 1980s, rebranded as the American Festival Theatre, as generic a company identity as one could ask for but hey, doesn’t everybody love a festival? It left in its wake an assortment of Shakespearean named businesses around it, which survived for years, despite the closure of the town’s major claim to the name.

Professionally, for these companies, the rebranding is rooted in solid marketing theory. In the case of the two going concerns, they have grown beyond being solely Shakespearean companies, though it’s worth noting that the Shaw Festival has not yet renounced old G.B., even as it has expanded its own repertoire. If Shakespeare is less prominent on the stage, perhaps it is best to not fly him as the company banner, especially since conventional wisdom holds that many people find the works of the playwright to be difficult and off-putting, a perception aided by years of dull literature teachers in secondary schools. If your name is a misrepresentation or worse a deterrent, business sense dictates that you remove the obstruction; when I was executive director of The O’Neill Theater Center, I quickly moved to rework the company’s logo after multiple people told me stories about its caricature of Eugene being frequently mistaken for Hitler.

While these demotions of old Will are extremely prominent, he’s not about to disappear from the North American consciousness. His works are omnipresent thanks to their eternal brilliance, as well as the added bonus of their being in the public domain, free from royalties or restrictive heirs. Every summer, Shakespeare in the Parks blossom as far as the eye can see, not only in New York’s Central Park, especially his most arboreal works like A Midsummer Night’s Dream and As You Like It. And of course we need only look to England where his works, and tributes to it, are a perpetual Shakespearean festival of which they are justly proud.

But there’s no missing the fact that the companies perhaps most credited with popularizing and sustaining Shakespeare in North America in the latter half of the 20th century have shrugged off their inspiration and their mascot, in the interest of sustaining themselves as centers of theatrical creativity. It’s hard to argue with that latter goal. After all, when theatre is restricted, or beholden to a limited, outdated artistic palette, it atrophies and dies.

But for all the business sense it makes, I can’t help feeling a pang of loss as Shakespeare’s name gets excised. Once a befuddled high schooler, who came to love Shakespeare as I saw ever-better productions following a dire Julius Caesar in 9th or 10th grade, it seems a small but significant chip away at Bill’s rep in The New World. For the theatres, it’s crucial re-branding. For The Shakespeare Brand, it’s a crucial loss.

Another round to Sanjay. Fortunately, after 400 years, I think Shakespeare’s still ahead. For now.

[Update 11/2/12: This post has been updated to reflect that the Stratford Festival has now dropped Shakespeare from its name twice in its history, which was not clearly reflected in the initial press reports that prompted this post.]

October 9th, 2012 § § permalink

The programme/script of Caryl Churchill’s new play

Like most American theatergoers, I’m always startled when I get to England and I’m expected to shell out £4 (about $6.40) if I want a theatre programme. This flies against the American tradition of free programs, regardless of whether you’re attending commercial or not for profit theatre; don’t confuse a program or Playbill with souvenir programs, those $20 photo galleries found on Broadway, at ice shows and circuses, and their like. When you calculate the cost of a theatre ticket in England against what’s charged here, there remains a significant savings, so I and other Americans should really keep our mouths shut about the extra tariff. Comparatively, we’re still getting a bargain.

That said, the experience reminds me once again about the nature of theatre programs, their purpose and their often unrealized value. That’s something that transcends price and international boundaries. At its simplest, the program gives us the basic info about the show we’re seeing: who did what and what they’ve done before. It’s a tool for telling us about the artists, and a great way of insuring that you’re not distracted by thoughts like, “Wait, is that the woman who was in…” while you should be focused on the story unfolding, not the identity of a performer.

Beyond that, programs can tell us more about the show we’re seeing, in the manner of a study guide for adults, with everything from impressionistic pages replicating art works and corollary quotes worth contemplating in relation to the show, to explicit essays which seek to tell us things we might not know, but should (at least in the eyes of the producer or artists). They can also tell us more, in the case of work produced by ongoing companies, about the people and organization responsible for the show; while this is often boilerplate, it’s institutionally necessary, just like those pages of donor acknowledgements.

In our media suffused era, programs have become tablet friendly; I’m seeing theatres making their entire program available on iPads in advance of the show, or downloadable as PDF files for those without the newest technology (he said, pointing to himself). I think that’s a terrific asset, especially if there’s something in the program that might prove particularly valuable to one’s appreciation of the work. Very often people read their programs after a show is over, so advance access is a great step forward – provided theatres make a distinction between programs and newsletters, and define a clear purpose and corresponding type of content for each.

I could ramble on all day about the nature and benefits of theatre programs, but let me cut to the chase with a particular and perhaps unique example. For many years, London’s Royal Court Theatre’s programmes have been copies of the play you’re seeing, an exceptional asset and value, especially at a venue dedicated to new plays. I know of many American companies that have long envied the Court, yet few have managed this feat of offering new scripts to their audiences; in this age of instant publishing and tablets, perhaps it’s time to look at it once again.

Last week, seeing Caryl Churchill’s new play Love and Information, which is comprised of dozens of vignettes that go far beyond the title topics while always managing to encompass one or the other (or both), I bought my Royal Court programme/script. When I got home that evening, I wasn’t about to immediately re-read the play, but I did decide to glance through it, foolishly thinking that the ever-enigmatic Ms. Churchill might offer some additional insight in the text. What I found profoundly changed my view of the play.

While there was no treatise on the piece, by the author or anyone else, there was a brief production note on the text that made the experience, in retrospect, even more fascinating. It reads:

The sections should be played in the order given but the scenes can be played in any order within each section.

There are random scenes, see at the end, which can happen at any time.

So what Ms. Churchill informed me, and anyone who bothered to read that text note, is that Love and Information is a theatrical erector set. While there are certain rules that must be followed (as in, say, architecture), there’s also a freedom to reimagine the work with every staging. Indeed, the optional scenes were not in the premiere production that I saw, but they’re still available for a director, leaving (or perhaps mandating) that the text be approached as malleable with every new iteration.

I don’t recall that reviews of Love and Information noted the unfixed nature of the play’s vignettes, suggesting that it wasn’t called out in the press materials or that some critics may have missed this note, which to me is vital. As part of a play which offers no conventional narrative and a highly fractured structure, it’s sure to set off lots of conversations. In her taciturn way, Ms. Churchill appears to be telling us that there’s no singular answer because there’s no singular version of the play. Mind blown.

Some will argue that what’s on stage should be all there is, and one can make a case for that. But I see nothing wrong in reaching out to audiences with some useful, and at times vital, information. In print or online, free or paid, programs can profoundly effect our understanding of what we see. The challenge that remains, no matter the price or the format, is how do we get people to take advantage of the information on offer, not because it’s “good for them,” but because it may open their minds to even greater insights and possibilities?

August 21st, 2012 § § permalink

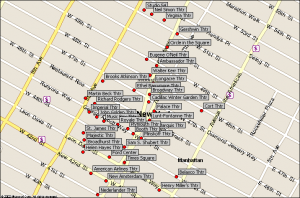

A map that includes most of the Broadway theaters, but it isn’t quite large enough and not completely up to date.

Having previously taken a quantitative look at new Broadway musicals and musical revivals, it was inevitable that I would look at play production on Broadway as well. So as not to bury my lede, let me begin with the list of playwrights who have had five or more productions on Broadway in the last 20 years, new or revival.

William Shakespeare (13)

Arthur Miller (12)

Tennessee Williams (11)

Eugene O’Neill (9)

Noel Coward, David Mamet, Neil Simon, Tom Stoppard (8)

August Wilson (7)

Anton Chekhov, David Hare, Terrence McNally, George Bernard Shaw (6)

Brian Friel, Richard Greenberg, Donald Margulies, Martin McDonagh (5)

What is immediately noticeable among these 17 playwrights? They’re all male. There is but a single playwright of color. Eight are not American. Six were dead during the 20 years examined. If anyone is looking for hard and fast data about the lack of diversity among the playwrights getting work on Broadway, this would be Exhibit A.

Now let’s get detailed. As indicated, I studied the past 20 years on Broadway, from the 1992-93 season through the just completed 2011-12 season; my study of musicals had covered 37 seasons, going back to the year that Chicago and A Chorus Line debuted. The 20 year mark for plays begins with the season that saw Tony Kushner’s Angels in America: Millennium Approaches premiere, arguably a work as significant a landmark in playwriting as A Chorus Line was to musicals.

The 20 year mark also encompasses significant shifts in production by not-for-profits on Broadway: Roundabout started out at the Criterion Center and by last year had three Broadway venues (American Airlines, Stephen Sondheim, Studio 54); Manhattan Theatre Club rehabilitated the Biltmore and began using it as their mainstage (later renaming it the Samuel G. Friedman); and Tony Randall’s National Actors Theatre grew and withered, as the more firmly established Circle in the Square evolved from producing company to commercial venue. Throughout, Lincoln Center Theatre produced in the Vivian Beaumont, considered a Broadway theatre virtually since it opened in the 60s, and continued its practice of renting commercial houses when a big hit monopolized the Beaumont. Commercial productions continued throughout this time in more than 30 other theatres, as did some productions by other not-for-profit producers without a regular home or policy of producing on Broadway.

So what is the scorecard of play production, both commercial and not for profit on Broadway over these last 20 years? 397 productions by 228 playwrights, with more than a quarter of the plays produced written by the 17 men listed above.

What of women? There were 43 women whose work appeared on Broadway in these two decades, but none saw more than three plays produced. The two women with three plays were Yasmina Reza and Elaine May (the latter’s count includes a one-act); four women each had two plays on the boards (Edna Ferber, Pam Gems, Theresa Rebeck and Wendy Wasserstein). Collectively, they make up slightly under 1/5 of the playwrights produced.

Because I have often been party to debates about whether or not not-for-profit companies should be considered part of Broadway, I ran the numbers without the productions of the five companies singled out above (RTC, MTC, LCT, NAT and CITS). Had they not been producing, and had no one taken their place, Broadway would have seen only 253 plays produced in those 20 years, nearly 1/3 less than the actual number, a significant reduction in activity.

And what of the balance between new plays and revivals? The 20 year breakdown of all productions showed 179 new plays and 218 revivals, but with the five not-for-profits are removed, it’s 140 new plays and 113 revivals. That shift is quite notable: the not-for-profit theatres on Broadway have only been responsible for 39 new works on Broadway over 20 years, but they’re the source of 105 revivals. That’s not so shocking, when you consider that NAT and CITS were focused on classics and that Roundabout’s original mission was solely classical work as well. But it certainly shows that without the not-for-profits, fewer vintage shows, whether from the recent or distant past, would have worn the banner of Broadway.

Now let’s go back to the list of playwrights with five or more plays on Broadway in the past 20 years, taking out the not-for-profit work. The results are:

David Mamet, Arthur Miller, William Shakespeare (8)

Neil Simon (7)

August Wilson (6)

Noel Coward, Martin McDonagh, Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams (5)

We drop from 17 playwrights making the cut to only 9, but its interesting to note that playwrights like Miller, O’Neill, Shakespeare, Williams and Wilson remain well represented, even in my theoretical scenario. As for women, the number produced drops to 31, roughly a quarter of the full count.

So what does this tell us, besides being fodder for trivia quizzes and feeding the current affinity for facts via list? It shows us that commercial producers are not all trendy money grubbers without interest in our theatrical past, since a number of classic works were produced under their aegis. That said, without the not-for-profits, the number of revivals overall would have been cut in half, showing how essential they are in maintaining Broadway’s heritage. For new work, the not-for-profits of Broadway play a smaller role to be sure, but its worth noting that a number of major playwrights wouldn’t have had any plays on Broadway in the past two decades without the not for profits, including Philip Barry, Caryl Churchill, William Inge, Warren Leight, Craig Lucas, Moliere, Sarah Ruhl, George Bernard Shaw, Regina Taylor and Wendy Wasserstein. In a startling irony, Sophocles and Euripides both were produced only commercially.

By its methodology, this glimpse at the past two decades inevitably shortchanges the influence of the not-for-profit theatre. It does not consider how many of the plays were commissioned by, developed by and first produced in not-for-profit companies in New York, nationally, or abroad, but many of the new plays in this period have those roots (and unlike musicals, plays are more typically produced without commercial enhancement in not-for-profits, with producers coming in later once a show has begun to achieve recognition). Because I didn’t have reliable resources to parse the partnership and capitalization of each Broadway production, shows from theatres like The Atlantic, New York Theatre Workshop and The Public, or even MTC pre-Biltmore, haven’t been categorized under not-for-profit, though they rightly might be; I believe based on anecdotal observance that (with sufficient time resources and manpower) we would see not-for-profits directly responsible for originating even more new plays.

It would be easy to argue that this study is at best intriguing but limited. After all, on a financial level, plays account for a marginal percentage of Broadway revenues, with musicals yielding the lion’s share of the grosses. One can also argue that Broadway, particularly when it comes to plays, is hardly representative of the full quantity and variety of new work being done in America, an opinion I hold myself.

But so long as Broadway remains a beacon for tourists, for theatre buffs and for the mainstream media, so long as it holds a fabled spot in the national and international imagination, plays on Broadway remain important, even if they are marginalized or unrepresentative. With all of the challenges that face producers, commercial or not-for-profit, who wish to mount plays, the public perception of American drama is still weighted towards Broadway, even if its mix of new plays and classics is but the tip of the iceberg, financially and creatively. We can debate whether Broadway is deserving of its still-iconic status, but so long as it exists, understanding exactly where plays fit in the equation can only serve to help them hold their ground, in the best interest of shows which don’t sing or dance, and the writers who are so committed to them.

* * *

Notes on methodology, beyond what’s explained in the text:

1. Although I have not provided the spreadsheets I constructed in order to work out my statistics, which list every play and playwright produced in the past 20 years, I feel it is incumbent upon me to name the female writers who have been produced on Broadway, with the hope that in the next 20 years, this list will make up a much greater percentage of writers produced: Jane Bowles, Carol Burnett, Caryl Churchill, Lydia R. Diamond, Joan Didion, Helen Edmundson, Margaret Edson, Eve Ensler, Nora Ephron, Edna Ferber, Pam Gems, Alexandra Gersten, Ruth Goetz, Frances Goodrich, Katori Hall, Carrie Hamilton, Lorraine Hansberry, Lillian Hellman, Marie Jones, Sarah Jones, Lisa Kron, Bryony Lavory, Michele Lowe, Clare Booth Luce, Emily Mann, Elaine May, Heather McDonald, Joanna Murray-Smith, Marsha Norman, Suzan-Lori Parks, Lucy Prebble, Theresa Rebeck, Yasmina Reza, Joan Rivers, Sarah Ruhl, Diane Shaffer, Claudia Shear, Anna Deavere Smith, Regina Taylor, Trish Vradenburg, Jane Wagner, Wendy Wasserstein, and Mary Zimmerman.

2. In the case of shows with multiple parts (Angels In America, The Norman Conquests, The Coast of Utopia), I have classified each as a single work.

3. Translations, adaptations, new versions – these are a particular challenge, since the contribution of the translator or adapter requires a value judgment on each and every effort. Consequently, I have chosen consistency, not artistry; for this study, only the original author received credit. Consequently, while David Ives is credited as the author of Venus in Fur, which is adapted from a book, only Mark Twain gets credit for Is He Dead?, even though I happen to know David’s contributions were significant on making the latter play stageworthy. Christopher Hampton is not recognized for his translations of Yasmina Reza’s plays, however elegant they may be, and I have ceded The Blue Room to Schnitzler, since it is firmly rooted in La Ronde. And so on.

4. Special events and one-person shows were judged according to whether, in my subjective opinion, they could reasonably and sensibly be performed by someone other than the author/performer. As a result, Billy Crystal’s 700 Sundays is not included in my figures, while Chazz Palmintieri’s A Bronx Tale makes the cut.

5. The number of plays produced annually on Broadway consistently outnumbers the musicals, despite, as already noted, musicals accounting for the lion’s share of Broadway revenues. I suspect, but haven’t the resources to confirm, that the number of overall performances of plays is also vastly less than the number of musical performances in a given year; numerous limited runs of 14 to 16 weeks for plays, even if there are more of them, are surely overwhelmed by the ongoing juggernauts of The Book of Mormon, Wicked, and others.

6. A handful of plays were written by writing teams: Kaufman and Ferber, Lawrence and Lee, etc. Each playwright was recognized in their own right. The same was true for the rare omnibus productions by separate authors, such as Relatively Speaking from Ethan Coen, Elaine May and Woody Allen.

7. I would have liked to break out the racial diversity of Broadway playwrights over the past two decades, but I had no reliable source for determining the heritage of every author, or how they may self-identify, therefore I felt it best not to guess.

8. It should go without saying that there are a number of playwrights who also work on musicals; if there is any barrier between the forms, it is highly permeable. My studies have by their nature been bifurcated between plays and musicals, but there is more fluidity than these articles might suggest.

9. When classifying plays as new or revival, in cases where they play had not been previously produced on Broadway but had prior life from years or decades earlier, I opted for the Tony Awards’ guidelines of new work being that which has not entered the standard repertory. So Donald Margulies’ Sight Unseen, produced with great success Off-Broadway and regionally over much of the period studied, was considered a revival.

10. I have drawn my data from the well-organized Playbill Vault, which expedited my research immeasurably. My thanks to those who assembled it.

June 14th, 2012 § § permalink

Anton Chekhov

- George Carlin

You needn’t be an English major to recognize that one of the words in my title is out of place. The second word is a verb, therefore unless theatrical texts have become anthropomorphized and begun getting it on with each other, the word is inappropriately used. You likely recognize that the word “fornicating” is a substitution for a common vulgarity, for which it is technically a synonym. Said vulgarity is fairly all-purpose, and is often used as a negative adjective. You will therefore accuse me of bowdlerizing my speech, perhaps to avoid offending some perceived notion of community or even professional standards. You would not be wrong. However, for the remainder of this post, I will abandon all euphemisms and employ, as appropriate, language from which I have heretofore abstained from in my internet and social media discourse. You are thusly warned. Those of delicate sensibilities may excuse themselves.

So…

This morning, Playbill wrote about Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company’s 2012-13 season of five plays, one of which is a world premiere adaptation of Chekhov’s The Seagull, by Aaron Posner, evocatively titled Stupid Fucking Bird. I know nothing about this particular version, but the title gives me the sense that it will perhaps be updated, and use a more colloquial patois than that usually associated with the master dramatist. Certainly anyone making a decision about whether to see the show will be unable to claim, should the language of the script echo that of the title, that they were caught unawares.

Of course, that decision-making may be impaired by media coverage announcing, featuring or reviewing that play because, in all likelihood, a number of media outlets will refrain from ever using the actual title. Some may drop the second word entirely, others may opt to print only “F——,” as if they’re fooling anyone. The theatre will face challenges in advertising the play, resorting to their own euphemisms if they desire to promote the work in compliance with the standards and practices of print and electronic media. On the other hand, they’ll likely get other coverage precisely because of this conundrum, though it will likely speak more of Carlin (George) and less of Chekhov (Anton).

This is hardly the first title to break the profanity barrier. English playwright Mark Ravenhill confronted us with Shopping and Fucking a number of years ago; Stephen Adly Guirgis confounded copy editors everywhere with The Motherfucker with the Hat just a couple of seasons back on Broadway. Dashes and asterisks got a workout with each of them, as did an entire range of smirks and jokes from on-air personalities. In some cases, advertising campaigns were altered midstream in a capitulation to public mores.

So-called profanity isn’t the only category of language that creates challenges for theatres and for those that cover it. The website address “cockfightplay.com” takes you to the current Off-Broadway hit Cock, since the title alone would apparently evoke undesirable connotations for some, the presence of a rooster silhouette notwithstanding. A number of years ago, a play by the late African-American writer John Henry Redwood, No Niggers, No Jews, No Dogs, caused an uproar for the Philadelphia Theatre Company, which premiered it. We may be a country founded on free speech, but our ongoing inability to define pornography and obscenity creates a grey area; inflammatory words employed knowingly for artistic and cultural reasons are verboten.

Now I’m not advocating that every play (or musical) should begin using (and advertising) titles that may run afoul of prevailing sensibilities. But I’m also not one to deny any artist the right to express themselves as they see fit, although they should be aware of the possible consequences that may befall them and their work, no matter how much a producer or theatre company may seek to support them. We’ve seen the phenomenon of ever more outrageous titles and topics being deployed in fringe festivals, but in that case it’s to help stand out from a mass of work and attract attention for brief runs in small venues. I don’t think Ravenhill, Posner, Redwood, or Cock’s Mike Bartlett were naïve in their title choices, they may have wished to shock, but I sort of doubt that marketing was their primary motivation.

Last night, on basic cable, the reboot of Dallas deployed “asshole” as an epithet, and I feel certain that I’ve heard it on various cop shows over the years. While Cock cannot be a title, “vagina” has become a ready punchline on network comedies, as has “penis”; perhaps it is the slang which makes it dirty? South Park, famously, had its characters say “shit” some 175 times in a single episode. I’m not talking about premium channels here; I’m talking about basic cable and broadcast. Frankly, often tuning in for The Daily Show a few minutes early every night, I can’t even believe some of what’s said on Comedy Central’s scripted series.

If we are not quite at a double standard, we are on a collision course when broadly accessible entertainment can be, to use a quaint old term, potty-mouthed, while the relatively narrow field of the arts are precluded from using the names they deem appropriate. Apparently, many fear unsuspecting 6-year-olds will stumble upon a newly profane New York Times Arts section, provoking uncomfortable conversations. Once upon a time, theatre was allowed greater latitude than movies and TV in what could be said or portrayed; the tables are now almost completely turned. Surely if children can be warned nightly about the dangers of a four-hour erection, “shocking” titles for plays aren’t going to do much harm.

Those who follow my Twitter feed know that I almost never tweet out reviews; I figure that there are plenty of others, including critics themselves, who do, so why be redundant. I focus my energies on highlighting material which may not have had the same kind of exposure.

Those who follow my Twitter feed know that I almost never tweet out reviews; I figure that there are plenty of others, including critics themselves, who do, so why be redundant. I focus my energies on highlighting material which may not have had the same kind of exposure.