August 7th, 2015 § § permalink

It would be hypocritical of me to speak out against precisely how people have expressed their feelings about, and to, Words Players Theatre in Rochester, Minnesota, because I spend so much of my time now speaking on behalf of the rights of artists to express themselves as they see fit. So as one of the first people to raise the issue of the play submission guidelines proffered by Words Players, I can only say that I’m disappointed in myself, for not engendering a more constructive dialogue.

It would be hypocritical of me to speak out against precisely how people have expressed their feelings about, and to, Words Players Theatre in Rochester, Minnesota, because I spend so much of my time now speaking on behalf of the rights of artists to express themselves as they see fit. So as one of the first people to raise the issue of the play submission guidelines proffered by Words Players, I can only say that I’m disappointed in myself, for not engendering a more constructive dialogue.

I’m not reneging on any of the points I raised with the blog post I put up last Saturday – I still see the guidelines as written as very problematic, and I want to see Words Players bring their short play festival’s selection and production model into line with widely accepted practice. I want to know that the young people who participate in this program are learning about the ethics of art as well as the practice of it, because even if Words Players turns out to be their only foray on stage, they can carry appreciation and respect for the work of creative artists through their lives, and maybe even stand and defend such work at some point in the future. I want other programs and producers to learn from this example.

Since Monday, I have been in touch by phone, by e-mail, by Facebook messenger and by text both with playwrights as well as with staff and parents at Words Players. I have seen numerous public communications and had private ones shared with me, as well as some that were intended to be public but were excised from public forums. I am extremely dismayed by the extraordinary level of invective, attack and profanity that has been hurled in the direction of Minnesota, just as I was deeply troubled by the seeming intent and implications of the original submission request. But I‘m not calling anyone out, or even quoting anyone, because I’d like us all to move forward together.

I won’t share any specifics from my assorted personal conversations because none of them were on the record. While I am an advocate, not a journalist, I believe I can only advocate for change if people can trust that when they speak to me, they are not immediately speaking to anyone who follows me on social media or reads my blog. But just as I worried about the lessons that Words Players was teaching to the young people who participate in their program, I’m now worried about the lessons the creative community and its allies (in which I certainly include myself) have inadvertently taught them as well, even in service of a position I strongly support.

When I first began writing about incidents of censorship, which in those early days was solely in the academic sphere, I admit I allowed my outrage to boil over at times in print. It made for good reading, I suppose, and there’s something cathartic about writing that way. But I think if you were to read all that I’ve written on the subject of artists’ rights and censorship since 2011, you’ll find that I’ve tempered my tone, even in some of the most egregious cases – at least I hope I have. Mind you, my anger at certain people who tried to silence or shut down, or manipulate the text of, certain plays and musicals is ever-present.

Of course, I am not a teacher who has been overruled, reprimanded or fired for choosing to produce a play. I am not a playwright who has seen their work trivialized or vandalized by a theatre (or theatres) over the course of pursuing my career. I have not been invited into some of these debates, but rather inserted myself. I recognize that all too readily. But I have made my life in the theatre and I hope it’s apparent to anyone who knows or reads me that it’s my goal to perhaps in some way leave it a little better, a little stronger, than it was when I came into the field.

So I’m not about to tell anyone exactly what they should think or say, seven days into the contretemps over Words Players. But I hope that can I ask everyone involved that they consider the true goals here, which are – I believe – to insure that the words of playwrights, novice or veteran, are treated as central, essential and the absolute domain of each playwright, as well as to see the young people at Words Players and beyond have the best possible experience with theatre and the arts.

To quote Travis Bedard’s 2amtheater blog post from yesterday, “Northland Words Theatre isn’t the enemy, they are us. They are a scrappy theatre trying to make stuff they love on a wing and a prayer. They got something wrong. So we help them fix it and help them to understand why we’re so shocked at the call.”

I wish I’d said that when I first wrote about issue. I’m genuinely sorry that I didn’t. I didn’t realize that perhaps I had to. I’ll try to do better in the future.

So here’s what I believe: a script is not a mere starting point – it is the point. It provokes dialogue between creative artists as they build a production in service of that script, it creates dialogue between those artists and audiences.

There’s still more conversation to be had on this subject, with Words Players and with other companies too. I’ll have that conversation for as long as people are willing to talk about it with me. I’ll welcome every voice that wants to participate, in the hope of persuading people to share my perspective, which is consistent with that of the vast majority of the creative community.

Ultimately, everyone has the right to express themselves as they see fit. But I’d like to suggest that perhaps we can all have a better conversation.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama.

August 3rd, 2015 § § permalink

A close facsimile of the Smith Corona typewriter I used for over a decade.

Last weekend, I shared a story and wrote a blog post about Dylan Lawrence, a 13-year-old in Lincoln, Nebraska who staged what appeared to be a fairly impressive production of Shrek The Musical in a neighbor’s backyard. The story seemed to touch an awful lot of people, perhaps because they responded as I had, when introducing the article on Facebook.

Sometimes, those of us who work in the theatre need a quick reminder of the impulse that got us started, which can get lost amid the realities of having made the thing we love into our job. That’s why I think this story is so terrific, because, in one way or another, wherever we grew up or however we got started, to paraphrase Lin-Manuel’s Tony acceptance rap, we were that kid. Let’s share this – let’s make Dylan Lawrence a star, for every kid out there making theatre in a backyard, a basement, or on Broadway.

Frankly, I found myself jealous of Dylan’s energy and initiative, wishing I had been that creative and entrepreneurial at his age, to the degree one can be jealous of someone today over one’s own perceived deficiencies 40 years in the past.

A few days later, I happened on a news story from the UK, announcing that a small London pub theatre would be producing the world premiere of a play by Arthur Miller. Impressed by such a discovery, I read on, only to learn that the unstaged play in question had been written by Miller as a 20-year-old college sophomore. Frankly, while Miller’s reputation is secure, I had to wonder whether the play in question would add to the Miller canon, if it would contradict some aspect of it (a la Go Tell A Watchman), or would it simply be a novelty that goes back into the Miller archives after this run.

These two incidents began to work on me, as did a flip comment I made, entirely in jest, to a Twitter commenter about the Miller story. I said something to the effect that I doubted if anyone wanted to read my unproduced plays.

Shortly thereafter, it hit me. I actually have some unproduced plays. Or at least I had them. I’m not digging through old files and boxes for them, for me or anyone else, and I’m really hoping that no one else has copies. But I am willing to share with you what I recall of my efforts, which I haven’t thought about in quite some time.

It’s worth noting that I saw very little theatre as a child. I attended a children’s theatre show at Long Wharf Theatre in 1967 for the fifth birthday of a kindergarten classmate, of which I remember nothing but the seeming vast darkness of that actually intimate space. In second grade, my parents took my brother and me to see the national tour of Fiddler on the Roof at the Shubert Theatre in New Haven, and what I remember most is “Tevye’s Dream.” It stands out not because I liked the number, but because as a child I was very skittish about anything supernatural, and so my parents had spent a lot of time preparing me for the appearance of Frumah Sarah. The anticipation was so significant, and the event so anticlimactic, that it was my greatest takeaway. My first Broadway show, circa 1975, was Stephen Schwartz’s The Magic Show. My second was Beatlemania.

Despite a paucity of real world examples, I conceived of a passion for theatre, and my parents enrolled me in a Saturday morning drama program at the New Haven YMCA. I believe I was in fourth grade. I dimly recall the space in which we worked, that there were only a few other kids involved, perhaps three or four, and I have no memory of the class leader. But I do remember that the program concluded with some manner of performance – I don’t even recall any audience – of the play I wrote for the group, Love and Hate. The plot? No idea. But remarkably, I do think that even then I was aware of a book called War and Peace, and that it sounded pretty good, so I mimicked the wide scope of its title. I suspect I performed in Love and Hate as well, but that aspect is too indistinct. My older brother wouldn’t have attended out of disinterest, so I can’t ask him about it, and my sister would have been to young to sit through it. With my parents gone, these threads are all that is left of Love and Hate.

My next writing efforts, some time during fifth and sixth grade, were both done under the tutelage of my synagogue’s cantor, one Solomon Epstein, who was a young Jewish man from the south whose lasting gifts to me included several of my formative cultural experiences, notably my first art museum visits, as well as my lingering tendency, despite my New England upbringing, to say “y’all.”

It was Cantor Epstein who had our second grade Hebrew school class sing a short pop cantata called Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, years before it was expanded into a stage show (I managed to tell Lord Lloyd Webber this story years later). He staged several similar, but longer, works as multimedia events on the synagogue’s stage – after all, this was the early 70s. I remember learning how to synchronize three sets of dual slide projectors with a big electrical box called a crossfader, and asking him whether the rabbi would permit him to have an attractive young woman of 17 or 18 years of age dance in the synagogue in a body suit (it was fine, apparently).

But he also encouraged me to write, going so far as to loan me a portable Smith Corona electric typewriter, which was so much easier than the vintage manual typewriter that dated from my parents’ school days, and probably before; they later bought me my own electric, the same model as the one I’d borrowed. First, I undertook to do my own adaptation of the Peanuts comics for the stage (an avowed fan of the strip and quite aware of You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown). I did little more than transcribe the various cartoons from the comics, which I had been cutting from the newspaper and pasting into scrapbooks for years, and arrange them in short scenes. My only innovation, not entirely surprising given my guide, was to invent a new character, a Jewish “Peanut” named “Tsvi,” which not so coincidentally is my Hebrew name. The title of this opus: Happiness is a Jewish Peanut. Clearly at that time I was seeking my cultural identity by placing myself among characters I loved.

Subsequently, I tackled a more significant project, adapting a novel, the name of which escapes me now. It was a wry Jewish fantasy about the lives of babies in heaven before they’re born and sent to earth, but it actually had a narrative, which ended with its main character being launched to meet its parents. I recall that in the book’s mythology, the philtrum, or “drip canal,” under our nose is where God snapped his fingers against us to bring us to mortal life send us to earth. Funny what stays with us, no? Again, I was probably transcribing more than writing, but as this was a several hundred page novel, I did have to assert some basic editing skills, if nothing else.

My last writing attempt never got beyond the outline phase, but it was a special high school project that proved too overwhelming. Looking back, it was utterly self-indulgent and also self-revelatory, a play in which I imagined a version of myself, to be played by me. This main character, a high school student in a school much like mine, was to look at the talents of other students I –I mean he – admired and then, in turn, he/I would demonstrate those very same talents, at least on a par with, if not better than, those I envied. It would have been great fodder for a therapist, but as drama, no doubt quite inert, albeit a showcase for whatever talents I actually had.

To be honest, I still have ideas for plays, and screenplays, from time to time, some of which have been turned over and over in my head for many years as the circumstances of the world, or of my life, have changed. I honestly believe one or two of them are pretty good, but I have found that my impulse to write is best served by the essay form, the blog form, because it allows me to pursue a single idea in a single writing session. It is the commitment of returning to the same story, over and over, day after day, tweaking, adjusting, and fixing endlessly that has staved off any real creative efforts. It is why I admire playwrights (and screenwriters, and novelists) so very much.

I unearth all of this now because of young Arthur Miller decades ago, because of young Dylan Lawrence today, and because of the countless youthful creative artists who may not yet realize that’s where they’re headed, who may not have the support and access that Dylan Lawrence, Arthur Miller and I all had. We know what happened with Miller, and I plan to follow and support Dylan in any way I can – as I will do as much as I’m able for any young person inspired by the arts, especially theatre, and I hope that holds true for those who read my blog.

As for me, I came to understand that I am not a dramatic storyteller, but an avid consumer of stories, who wants nothing more than to play some role in their getting told, and in supporting and knowing those who tell them. Just as there are undoubtedly countless young artists and administrators – and audiences – to be nurtured, I hope there are at least as many parents, mentors and teachers to pave the way, declining budgets and skittish authority figures be damned.

And check back with me in about 20 years. Maybe by then I’ll have enough material for a marginally entertaining one-man show. You never know.

August 1st, 2015 § § permalink

I should say right up front that, until about two hours before I began writing, I didn’t know anything about the Words Players Theatre of Rochester, Minnesota or its parent organization, Northland Words. I only learned about them because the company had raised the online ire of people in the creative community. In particular, what caught my eye was a blog post by playwright Donna Hoke, “Dissecting The Most Disgusting Call For Plays I’ve Ever Seen,” in which she does exactly what she says she’s going to do in her title, line by line, word by word. I share her concern, but I’d like to take a macro view of the message that the company appears to be sending.

I should say right up front that, until about two hours before I began writing, I didn’t know anything about the Words Players Theatre of Rochester, Minnesota or its parent organization, Northland Words. I only learned about them because the company had raised the online ire of people in the creative community. In particular, what caught my eye was a blog post by playwright Donna Hoke, “Dissecting The Most Disgusting Call For Plays I’ve Ever Seen,” in which she does exactly what she says she’s going to do in her title, line by line, word by word. I share her concern, but I’d like to take a macro view of the message that the company appears to be sending.

Throughout their call for plays for Words Players 2015 Original Short Play Festival, the company’s director Daved Driscoll says several things worthy of admiration: there’s a commitment to young performers, as well as a desire to find work which he feels will appeal to his local community. I don’t think anyone would argue with those goals.

But where his message gets into trouble is, first, in the margins, so to speak. “Our emphasis is perhaps less on the artist-centered goal of producing ‘great art’,” he writes; elsewhere he notes “our desire to give writers and directors first-hand experience of the vagaries of ‘marketability’ as much as the more arcane goals of ‘art’.” If Words Players’ primary goal is to sell tickets, that’s perfectly fine, but that intimates that their efforts are more commercial than not-for-profit, and Northland Words is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization. Yet plenty of not-for-profits are accused of chasing sales over creative pursuits, so they’re not alone, but it’s awfully dissonant to be asking for plays from artists while dissing art itself. Why not focus affirmatively on what’s sought, rather than what’s not wanted? Instead, Words Players notes, “We prefer most of all plays that are significant and interesting, without off-putting superciliousness.”

Secondly, Driscoll states that, “We largely ignore considerations of age, race and gender in our casting decisions.” While that would be jarring in a professional setting, it’s perhaps somewhat less troubling in a company that’s focused on youth. After all, Lin-Manuel Miranda has noted that he doesn’t mind when schools without Latino students perform In The Heights, because once kids hit college, they’re going to be typed and should have a certain freedom to play any role while very young, though he does ask that they give respect to the culture they portray, and neither paint their skin nor adopt bad accents in doing so. However, Miranda doesn’t condone willfully altering the characters themselves, let alone the story, and neither do I. That choice should be the playwright’s, not the director’s or the artistic director’s.

I’d also suggest that in pointing out his youth emphasis, Driscoll could do better than, “The audience invariably includes a large percentage of young people. We will prefer scripts that appeal to them as well as to old, non-young people.” I believe most old, non-young people like myself wouldn’t mind at all that the work is for and by the young, were our decrepit state not reinforced redundantly. Honestly, young people play adults all the time in school theatre and community theatre where casts are young, so it’s not really an issue.

But what moves beyond poor communications and into the realm of unacceptable is how Driscoll speaks of how the theatre will handle the work of the very writers he’s soliciting. “Our production of the play is our only ‘compensation’ for its use,” he writes, later emphasizing the point by saying, “We don’t pay for the scripts.” Now if there are youthful writers in the local community who are the peers of the performers, who wish to write and be part of the program, that seems fair, provided no one else is getting paid either. But in a call for submissions that has clearly reached beyond the confines of Words Players and even Rochester. Minnesota, the idea that playwrights should give the company their scripts gratis devalues the work of writers – and if the youthful acting company knows of this, it suggests to them that writers’ words have no value.

Compounding this perspective, Driscoll writes, “While authors are welcome to confer with the directors, such conference is at the discretion of each director. Student directors will develop their autonomous interpretation and will maintain independent control of each production. They will in all probability modify settings and dialogue to fit our production situation and their own visions of the shows. Directors will, in particular, strive to make each play ‘entertaining’ to our audiences and may modify the scripts, accordingly.” This is the behavior of Hollywood studios towards writers, and they pay huge piles of money for that right; in the theatre, while a work is under copyright, the playwright has the final say about what words are spoken, unless they’re inveigled into giving away that right.

Finally, there’s a mission statement at the bottom of the call for plays which reads, in part, as follows: “Merely preserving ‘the way it was done’ is for mummies and pottery shards, not performance art.” I agree, but there’s a difference between fresh interpretations and wholesale vandalism, especially when a play is new and in no way trapped in amber.

Every theatre can set its play selection guidelines as it sees fit, but Words Players seems to be emphasizing the players over the words, and insulting playwrights in the process. The guidelines bother me for the same reason it bothers me when school administrators and professional directors and many others mess with copyrighted texts without permission: because not only is it in most cases legally and always ethically wrong (at least in the U.S.), it’s setting such a disastrous example for the young people who witness this disregard, bordering on contempt, for the writer’s art.

It’s unclear how many plays will be in the Words Players festival, how many people will attend and what they might be charged. But when it comes to compensation, royalties for amateur productions of short works are often little more than the price of a couple of movie tickets and a bag of popcorn, so they’re hardly onerous for any company. But no payment gives a licensee the right to have its way unilaterally with the text in theatre, unless the playwright inexplicably chooses to grant it.

Online, people wrote that they saw this same call last year and spoke out about it, but that it’s unchanged – they were ignored. Facebook and Twitter posts suggest that Words Players response has been, essentially, “if you don’t like it, then don’t submit.” They’ve been removing dissent from their social media. They’re trying to hide the efforts of those that might inform their community of reasonable standards and guide them towards more appropriate behavior.

I’m not writing just on behalf the playwrights – I’m writing on behalf of every single kid in that program. If those kids admire theatre and the arts, then regardless of whether they become professional artists or simply audience members in the future, any adults giving them training need to distinguish between creative rights and wrongs for them now, because they are the path to our future and to the health of the theatre.

In the call for plays by Words Players, Mr. Driscoll is teaching bad lessons (Donna Hoke has made some strong points on that as well). Either he should choose the plays he wants and treat them with respect, or he should write them himself and let the directors and performers have at them if he likes. The latter choice is his right if he is the author. But no one should be asking for plays if they’re not going to produce them with professional conduct and ethical standards, even for only one or two performances with a cast of young people in Rochester, Minnesota. Every play has meaning, as does every production, and Words Players will best serve its community by altering its practices to set the right example.

Update, August 5, 3:30 pm: Yesterday, Doug Wright, president of The Dramatists Guild, sent a letter to Daved Driscoll of Words Players outlining the reasons why playwrights and the Guild were so troubled by the theatre’s play submission guidelines. This morning, Driscoll responded in writing to the Guild, and subsequently did an interview with Playbill discussing their desire to conform to professional and ethical standards. Conversations between those parties will be ongoing, and if welcome, I hope to participate in them as well.

Update, August 7, 2 pm: The conversations online and offline surrounding this topic have, in some cases, metastasized far beyond my intent and perhaps the intent of others who drew attention to this situation. I hope you’ll read my followup post as well, “Writing A Different Script About Respect for Playwrights.”

Note: an earlier version of this post contained two photos of prior productions in the Words Players Original Short Plays Festival. While the photos were made available for download without restriction on the company’s website, I have removed them at the suggestion of several commenters.

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at The New School for Drama.

March 31st, 2015 § § permalink

Hannah Cabell and Anna Chlumsky in David Adjmi’s 3C at Rattlestick Theatre (Photo: Joan Marcus)

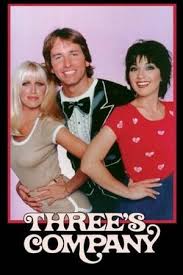

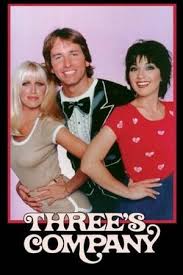

After nearly three years during which playwright David Adjmi was prevented from authorizing any productions of, or the publication of, his play 3C, a dark parody of Three’s Company, he has emerged as the victor in his legal battle with DLT Entertainment, which sought to silence the play, charging copyright infringement. Adjmi’s assertion of fair use was confirmed in the judgment.

Quoting from the ruling by Judge Loretta A. Preska, Chief United States District Court Judge in the Southern District of New York:

“Adjmi wishes to authorize publication of 3C and licensing of the play for further production and therefore brings this action seeking a declaration that 3C does not infringe DLT’s copyright in Three’s Company. Adjmi’s motion is GRANTED…”

The 56-page ruling goes on to summarize the play in detail, and then moves to discussion of the ruling, including:

“There is no question that 3C copies the plot premise, characters, sets and certain scenes from Three’s Company. But it is well recognized that “[p]arody needs to mimic an original to make its point, and so has some claim to use the creation of its victim’s. . .imagination.” Campbell, 510 U.S. at 581. The “purpose and character” analysis assumes that the alleged parody will take from the original; the pertinent inquiry is how the alleged parody uses that original material.

“Despite the many similarities between the two, 3C is clearly a transformative use of Three’s Company. 3C conjures up Three’s Company by way of familiar character elements, settings, and plot themes, and uses them to turn Three’s Company’s sunny 1970s Santa Monica into an upside-down, dark version of itself. DLT may not like that transformation, but it is transformation nonetheless.”

In conclusion, the judge wrote:

“The play is a highly transformative parody of the television series that, although it appropriates a substantial amount of Three’s Company, is a drastic departure from the original that poses little risk to the market for the original. The most important consideration under the Section 107 analysis is the distinct nature of the works, which is patently obvious from the Court’s viewing of Three’s Company and review of the 3C screenplay-materials properly within the scope of information considered by the Court in deciding this motion on the pleadings. Equating the two to each other as a thematic or stylistic matter is untenable; 3C is a fair use “sheep,” not an “infringing goat.” See Campbell, 510 U.S. at 586.

“This finding under the statutory factors is confirmed and bolstered by taking into account aims of copyright, as the Court has done throughout.”

Congratulations to Adjmi, to his attorney Bruce E.H. Johnson of Davis Wright Tremaine, to the Dramatists Guild and the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund for their amicus curiae brief in support of Adjmi, and everyone who participated in this fight for authors’ rights and creative freedom.

So, now my question is, what company will be the first to produce 3C now that they’re allowed to at long last, and when can I come and see it?

Howard Sherman is director of the Arts Integrity Initiative at the New School for Drama.

February 10th, 2015 § § permalink

Hannah Cabell and Anna Chlumsky in David Adjmi’s 3C at Rattlestick Playwrights Theater (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Seen any good productions of David Adjmi’s play 3C lately?

Sorry, that’s a trick question with a self-evident answer: of course you haven’t. That’s because in the two and a half years since it premiered at New York’s Rattlestick Playwrights Theater, no one has seen a production of 3C because no one is allowed to produce it, or publish it. Why, you ask? Because a company called DLT Entertainment doesn’t want you to.

3C is an alternate universe look at the 1970s sitcom Three’s Company, one of the prime examples of “jiggle television” from that era, which ran for years based off of the premise that in order to share an apartment with two unmarried women, an unmarried man had to pretend he was gay, to meet with the approval of the landlord. It was a huge hit in its day, and while it was the focus of criticism for its sexual liberality (and constant double entendres), it was viewed as lightweight entertainment with little on its mind but farce and sex (within network constraints), sex that never seemed to actually happen.

Looking at it with today’s eyes, it is a retrograde embarrassment, saved only, perhaps, by the charm and comedy chops of the late John Ritter. The constant jokes about Ritter’s sexual façade, the sexless marriage of the leering landlord and his wife, the macho posturings of the swinging single men, the airheadedness of the women – all have little place in our (hopefully) more enlightened society and the series has pretty much faded from view, save for the occasional resurrection in the wee hours of Nick at Night.

In 3C, Adjmi used the hopelessly out of date sitcom as the template for a despairing look at what life in Apartment 3C might have been had Ritter’s character actually been gay, had the landlord been genuinely predatory and so on. It did what many good parodies do: take a known work and turn it on its ear, making comment not simply on the work itself, but the period and attitudes in which it was first seen.

Enter DLT, which holds the rights to Three’s Company. They sent a cease and desist letter to Adjmi back in 2012 claiming that the show violated their copyright; Adjmi said he couldn’t afford to fight it. Numerous well-known playwrights wrote a letter in support of Adjmi and the controversy generated its first wave of press, including pieces in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Over time, there have been assorted legal filings by both parties, with another wave of press appearing last year just about this time, when Adjmi sued for the right to reclaim his play for production, with commensurate press coverage once again from the Times and Studio 360, among others.

Enter DLT, which holds the rights to Three’s Company. They sent a cease and desist letter to Adjmi back in 2012 claiming that the show violated their copyright; Adjmi said he couldn’t afford to fight it. Numerous well-known playwrights wrote a letter in support of Adjmi and the controversy generated its first wave of press, including pieces in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Over time, there have been assorted legal filings by both parties, with another wave of press appearing last year just about this time, when Adjmi sued for the right to reclaim his play for production, with commensurate press coverage once again from the Times and Studio 360, among others.

Why do I dredge this all up now? Because the bottom line is that DLT is doing its level best to prevent a playwright from earning a living, and throwing everything they can into a specious argument to do so. They say, both in public comments and in their filings, that 3C might confuse audiences and reduce or eliminate the market for their own stage version (citing one they commissioned and one for which they granted permission to James Franco). They cite negative reviews of 3C as damaging to their property. And so on.

But while I’m no lawyer (though I’ve read all of the pertinent briefs on the subject), I can make perfect sense out of the following language from the U.S. Copyright Office, regarding Fair Use exception to copyright (boldface added for emphasis):

The 1961 Report of the Register of Copyrights on the General Revision of the U.S. Copyright Law cites examples of activities that courts have regarded as fair use: “quotation of excerpts in a review or criticism for purposes of illustration or comment; quotation of short passages in a scholarly or technical work, for illustration or clarification of the author’s observations; use in a parody of some of the content of the work parodied; summary of an address or article, with brief quotations, in a news report; reproduction by a library of a portion of a work to replace part of a damaged copy; reproduction by a teacher or student of a small part of a work to illustrate a lesson; reproduction of a work in legislative or judicial proceedings or reports; incidental and fortuitous reproduction, in a newsreel or broadcast, of a work located in the scene of an event being reported.”

As someone who has gone out on a limb at times defending copyright and author’s rights, I’d be the first person to cry foul if I thought DLT had the slightest case here. But 3C (which I’ve read, as it’s part of the legal filings on the case) is so obviously a parody that DLT’s actions seem to be preposterously obstructionist, designed not to protect their property from confusion, but to shield it from the inevitable criticisms that any straightforward presentation of the material would now surely generate.

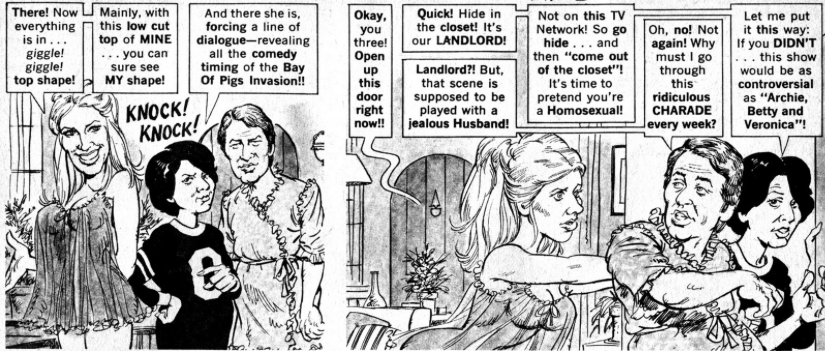

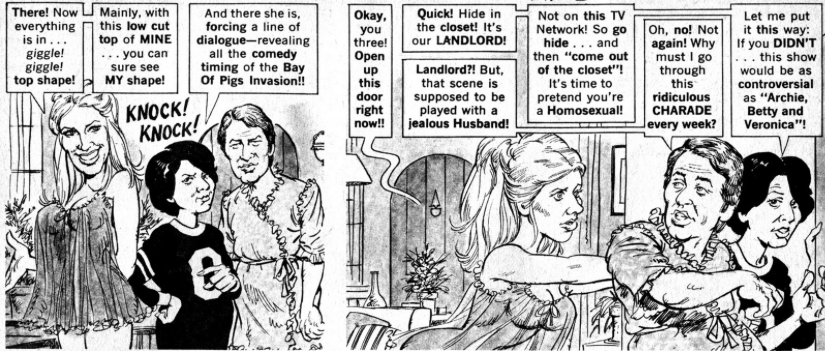

Rather than just blather on about the motivations of DLT in preventing Adjmi from having his play produced and published, let me demonstrate that their argument is specious. To do so, I offer the following exhibit from Mad Magazine:

What’s fascinating here is that Mad, a formative influence for countless youths in the 60s and 70s especially, parodied Three’s Company while it was still on the air, seemed to already be aware of the show’s obviously puerile humor, was read in those days by millions of kids – and wasn’t sued for doing so. That was and is a major feature of Mad, deflating everything that comes around in pop culture through parody. The fact is, Adjmi’s script is far more pointed and insightful than any episode of Three’s Company and may well work without deep knowledge of the original show, just like the Mad version.

The most recent filing in the Adjmi-DLT situation comes from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, an offshoot of The Dramatists Guild. Like all of the filings in this case, it’s very informative about copyright in general and parody in particular, and it spells out the numerous precedents where the use of a prior work was permitted under fair use, with particular attention to the idea that when the new work is transformative – which 3C surely is – it is permitted (read the complete amicus curiae brief here). In addition to their many examples, I would add from my own misspent youth such works as Bored of the Rings, a 1969 book-length parody of Tolkien by some of the people who would go on to create the National Lampoon, where incidentally, DLDF president John Weidman exercised his own comic skills) and Airplane!, which took its plotline (and punctuation mark) of a poisoned airline crew directly, uncredited, from the 1957 film Zero Hour! More recently, the endlessly touring Potted Potter has successfully run without authorization, though clearly derived from the works of J.K. Rowling and prior to any authorized stage interpretation.

The most recent filing in the Adjmi-DLT situation comes from the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, an offshoot of The Dramatists Guild. Like all of the filings in this case, it’s very informative about copyright in general and parody in particular, and it spells out the numerous precedents where the use of a prior work was permitted under fair use, with particular attention to the idea that when the new work is transformative – which 3C surely is – it is permitted (read the complete amicus curiae brief here). In addition to their many examples, I would add from my own misspent youth such works as Bored of the Rings, a 1969 book-length parody of Tolkien by some of the people who would go on to create the National Lampoon, where incidentally, DLDF president John Weidman exercised his own comic skills) and Airplane!, which took its plotline (and punctuation mark) of a poisoned airline crew directly, uncredited, from the 1957 film Zero Hour! More recently, the endlessly touring Potted Potter has successfully run without authorization, though clearly derived from the works of J.K. Rowling and prior to any authorized stage interpretation.

It’s been months since there have been filings for summary judgment in the case (August 2014, to be precise), and according to Bruce Johnson, the attorney at Davis Wright Tremaine in Seattle who is leading the fight on Adjmi’s behalf, there is no precise date by which there will be a ruling. Some might say that I’m essentially rehashing old news here, but I think it’s important that the case remains prominent in people’s minds, because it demonstrates the means by which a corporation is twisting a provision of copyright law to prevent an artist from having his work seen – and that’s censorship with a veneer of respectability conferred by legal filings under the umbrella of commerce. There may be others out there facing this situation, or contemplating work along the same lines, and this case may be suppressing their work or, depending upon the ultimate decision, putting them at risk as well.

We don’t all get to vote on this, unfortunately. But even armchair lawyers like me can see through DLT’s strategy. I just hope that the judge considering this case used to read humor magazines in his youth, which should provide plenty of precedent above and beyond what’s in the filings. 3C may take a comedy and make it bleak, but there’s humor to be found in DLT’s protestations, which are (IMHO) a joke.

P.S. I don’t hold the copyright to any of the images on this page. I’m reproducing them under Fair Use. Just FYI.

December 29th, 2014 § § permalink

Hands on a Hardbody at Houston’s Theatre Under The Stars

Are these my “best” blog posts of 2014? I couldn’t say. All I know is that they’re my most read, from a year in which page views on my site more than doubled over 2013.

Certainly 2014 was a year in which my writing found more focus, and whether the most-read posts bear out readers’ interest in that focus, or are simply a byproduct of a somewhat narrower range of subjects, I also don’t know. But if you’ve only discovered me part way through the year, or only read me sporadically, maybe there are a few posts here that escaped your attention, and if you’re interested, this will save you some scrolling and clicking.

Curtain call for Little Shop of Horrors at Jonathan Law High School

Before I start the official list, I want to bring your attention to a post which finished just out of the Top 10, the sad and yet remarkable story which bears out the sentiment “the show must go,” even when the show is a high school musical and when one of the cast members is murdered. To me, this story encapsulates so much about what theatre can offer, even at the worst times.

May 5: On Stage In Milford, With Sweet Understanding

Here’s the full rundown of the Top 10, in publication order, with some related posts included in my comments so as not to be too repetitive. Clicking on the titles will take you to the individual pieces.

January 22: Who Thinks It’s OK to ‘Improve’ Playwrights’ Work?

Was I surprised by this instance of unauthorized text alterations to a Brian Friel play at the Asolo Rep? Yes. But this turned out to merely be the precursor to a more widely-known incident yet to come, in Texas in June. Still, it was evidence that the issue of copyright and author’s rights isn’t just about high schools tinkering with “inappropriate” content – it can happen anywhere.

March 3: When A Theatre Review Condescends

It’s not usually fair to criticize a critic for a review of a production, since it’s their opinion, so when I wrote this piece taking a Philadelphia critic to task, I tried to do so on the basis of text and fact, not opinion. I received a lot of response about this piece, a great deal of it privately.

March 26: How You Can Save Arts Journalism Starting Right Now

Some found my stated “solution” overly simplistic, so either I failed to make, or they failed to recognize, my point about arts journalism lasting only as long as the metrics bear out an interest on the part of readers.

May 28: A Whispered Broadway Milestone No One’s Cheering

If you find me rather grouchy every Monday at 3 pm, it’s because that’s when the Broadway grosses are released, with one or more shows variously pronouncing the achievement of a new “sales record.” A number of outlets report these figures week in and week out, even though there’s usually a limited amount of actual news that matters to anyone outside the business. The “season” and “annual” compilation figures tend to provoke me even more, due to the perpetually positive spin even when the real story can be found by looking just a bit more carefully at the numbers.

June 3: When The Audience Bellows Louder Than Big Daddy

I was a bit surprised that this piece got the attention it did, as I wrote it after several West Coast outlets had already reported on this incident. Why my account drew lots of eyes I’ll never know, but I do hope it’s used in many arts management classrooms to speak to the essential nature of a well-trained front of house staff, no matter what size your theatre may be.

June 13: Into The Woods With Misplaced Outrage

The movie’s out. Now people can like the changes or not, but at least they’re judging the complete work, not stray accounts (which even Sondheim ended up disavowing). I’m seeing it on New Year’s Eve, FYI.

June 20: Rebuilding “Hardbody” At A Houston Chop Shop

I remain the only writer to interview Theater Under the Stars artistic director Bruce Lumpkin about his reworking of the text and score of the musical Hands On A Hardbody. The theatre pretty much circled the wagons as soon as my piece came out, even declining to speak with American Theatre magazine when Isaac Butler looked at the incident and the issue a few months later.

June 26: Under-The-Radar Transition at Women’s Project Theater

Let’s hear it for anonymous tips! I was the first to report this story, an unpleasant account of the ousting of an artistic leader by a board that sought to portray it as a voluntary separation (foreshadowing the scenario between Ari Roth and Theater J just this month). I do find myself wondering why the outcry over Theater J has been so much greater, when the Women’s Project situation had some notable similarities.

September 19: In Pennsylvania, Director Is Fired Over School “Spamalot”

September 19: In Pennsylvania, Director Is Fired Over School “Spamalot”

This was certainly the biggest school theatre censorship story of the year that I covered, as it played out over the course of nearly four months, from when it was first reported in the local Pennsylvania media. It was the final, unfortunate post that received the most attention, but for those who don’t want to start at the end, two other highly read posts on the situation in South Williamsport PA were “Trying To Find Out A Lot About A Canceled Spamalot” (July 15) and “Facts Emerge About School ‘Spamalot’ Struck Out Over Gay Content” (August 21). I wish I had written a blunter headline for the latter story, because it revealed that school officials had indeed lied about the reasons behind the cancelation of the show, and I regret not calling them out as strongly as possible. To my knowledge, they have not been held to account for spreading disinformation.

October 21: How To Fail At Canceling The Most Popular Play In High School Theatre

While the school was let off the hook for buckling under to outside pressure because the students took matters into their own hands, it’s encouraging to know that their production of Almost, Maine is only weeks away, as detailed in “Falling For ‘Almost, Maine’ in North Carolina in January.”

Though I don’t place it in the official Top 10, because it’s a compilation rather than something I actually “wrote,” my piece chronicling the censorship and restoration of work by my friends at the Reduced Shakespeare Company as they embarked on a tour starting in Northern Ireland is also one of my most read for 2014.

January 26: “The Reduced Shakespeare Controversy (abridged).”

Finally, my thanks to you for reading, clicking, liking, favoriting and sharing, and for your comments on the posts themselves, on Twitter and on Facebook. It’s truly appreciated.

December 3rd, 2014 § § permalink

Not to dash anyone’s dreams, but I think it’s fair to say that the majority of the hundreds of thousands of students who participate in high school theatre annually will not go on to professional careers in the arts. The same holds true for the student musicians in orchestras, bands and ensembles. They all benefit from the experience in many ways: from the teamwork, the discipline and the appreciation of the challenge and hard work that goes into such endeavors, to name but a few attributes.

But for some students, those high school experiences may be the foundation of a career, of a life, and it’s an excellent place for skills and principles to be taught. As a result, I have, on multiple occasions, heard creative artists talk about their wish that students could learn about the basics of copyright, which can for writers, composers, designers, and others be the root of how they’ll be able to make a life in the creative arts, how their work will reach audiences, how they’ll actually earn a living.

I’m not suggesting that everyone get schooled in the intricacies of copyright law, but that as part of the process of creating and performing shows, students should come to understand that there is a value in the words they speak and the songs they sing, a concept that’s increasingly frayed in an era of file sharing, sampling, streaming and downloading. Creative artists try to make this case publicly from time to time, whether it’s Taylor Swift pulling her music from Spotify over the service’s allegedly substandard rate of compensation to artists or Jason Robert Brown trying to explain why copying and sharing his sheet music is tantamount to theft of his work. But without an appreciation for what copyright protects and supports, it’s difficult for the average young person to understand what this might one day mean to them, or to the people who create work that they love.

* * *

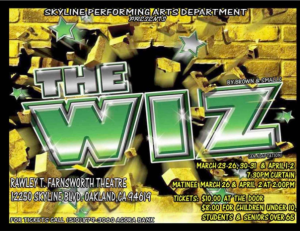

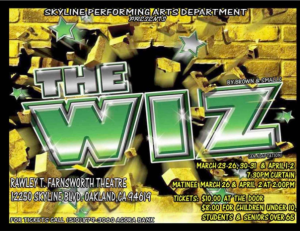

All of this brings me to a seemingly insignificant example, that of a production of the musical The Wiz at Skyline High School in Oakland, California back in 2011. Like countless schools, Skyline mounted a classic musical for their students’ education and enjoyment, in this case playing eight performances in their 900 seat auditorium, charging $10 a head. These facts might be wholly unremarkable, except for one salient point: the school didn’t pay for the rights to perform the show.

All of this brings me to a seemingly insignificant example, that of a production of the musical The Wiz at Skyline High School in Oakland, California back in 2011. Like countless schools, Skyline mounted a classic musical for their students’ education and enjoyment, in this case playing eight performances in their 900 seat auditorium, charging $10 a head. These facts might be wholly unremarkable, except for one salient point: the school didn’t pay for the rights to perform the show.

The licensing house Samuel French only learned this year about the production, and consequently went about the process of collecting their standard royalty. Over the course of a few months, French staff corresponded with school staff and volunteers connected with the drama program, administration and ultimately the school system’s attorney. French’s executive director Bruce Lazarus shared the complete correspondence with me, given my interest in authors’ rights and in school theatre.

I’m very sympathetic to any school that wants to give their students a great arts experience, and so the drama advisor’s discussion in the correspondence of limited resources and constrained budgets really struck me. Oakland is a large district and Skyline is an inner-city school; I have no reason to doubt their concerns about the quoted royalty costs for The Wiz being beyond their means. But their solution to this quandary took them off course.

I’m very sympathetic to any school that wants to give their students a great arts experience, and so the drama advisor’s discussion in the correspondence of limited resources and constrained budgets really struck me. Oakland is a large district and Skyline is an inner-city school; I have no reason to doubt their concerns about the quoted royalty costs for The Wiz being beyond their means. But their solution to this quandary took them off course.

Skyline claims that they did their own “adaptation” of The Wiz, securing music online and assembling their own text, under the belief that this released them from any responsibility to the authors and the licensing house. While they tagged their ads for the show with the word “adaptation,” it’s a footnote, and if one looks at available photos or videos from the production, it seems pretty clear that their Wiz is firmly rooted in the original material, even the original Broadway production. Surely the text was a corruption of the original and perhaps songs were reordered or even eliminated. It’s also worth noting that Skyline initially inquired about the rights, but then opted to do the show without an agreement.

* * *

OK, so one school made a mistake over three and a half years ago – what’s the big deal? That brings me to the position taken by the Oakland Unified School District regarding French’s pursuit of appropriate royalties. OUSD has completely denied that French has any legitimate claim per their attorney, Michael L. Smith. In a mid-October letter, Mr. Smith cites copyright law statute of limitations, saying that since it has been more than three years since the alleged copyright violation, French is “time barred from any legal proceeding.” Explication of that position constitutes the majority of the letter, save for a phrase in which Mr. Smith states, “As you are likely aware, there are limitations on exclusive rights that may apply in this instance, including fair use.”

As I’m no attorney, I can’t research or debate the fine points of statutes of limitation, either under federal or California law. However, I’ve read enough to understand that there’s some disagreement within the courts, as to when the three-year clock begins on a copyright violation. It may be from the date of the alleged infringement itself, in this case the date of the March and April 2011 performances, but it also may be from the date the infringement is discovered, which according to French was in September 2014. We’ll see how that plays out.

The passing allusion to fair use provisions is perhaps of greater interest in this case. Fair use provides for the utilization of copyrighted work under certain circumstances in certain ways. Per the U.S. Copyright office:

Copyright Law cites examples of activities that courts have regarded as fair use: “quotation of excerpts in a review or criticism for purposes of illustration or comment; quotation of short passages in a scholarly or technical work, for illustration or clarification of the author’s observations; use in a parody of some of the content of the work parodied; summary of an address or article, with brief quotations, in a news report; reproduction by a library of a portion of a work to replace part of a damaged copy; reproduction by a teacher or student of a small part of a work to illustrate a lesson; reproduction of a work in legislative or judicial proceedings or reports; incidental and fortuitous reproduction, in a newsreel or broadcast, of a work located in the scene of an event being reported.”

* * *

Rather than parsing the claims and counterclaims between Samuel French and the school district, I consulted an attorney about fair use, though in the abstract, not with the specifics of the show or school involved. I turned to M. Graham Coleman, a partner at the firm of Davis Wright Tremaine in their New York office. Coleman works in all legal aspects of live theatre production and counsels clients on all aspects of copyright and creative law. He has also represented me on some small matters.

“In our internet society, “ said Coleman, “there is a distortion of fair use. We live in a world where it’s so easy to use someone’s proprietary material. The fact that you based work on something else doesn’t get you off the hook with the original owner.”

Without knowing the specifics of Skyline’s The Wiz, Coleman said, “They probably edited, they probably varied it, but they probably didn’t move it into fair use. Taking a protectable work and attempting to ‘fair use’ it is not an exercise for the amateur.”

Regarding the language in fair use rules that cite educational purposes, Coleman said, “Regardless of who you are, once you start charging an audience admission, you’re a commercial enterprise. Educational use would be deemed to mean classroom.”

While Coleman noted that the cost of pursuing each and every copyright violation by schools might be cost prohibitive for the rights owners, he said that, “It becomes a matter of principle and cost-effectiveness goes out the window. They will be policed. Avoiding doing it the bona fide way will catch up with you.”

* * *

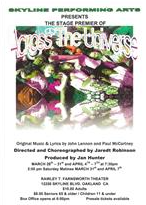

That’s where the Skyline scenario gets more complicated – because their “adaptation” of The Wiz wasn’t their only such appropriation of copyrighted material. In 2012, the school produced a stage version of Julie Taymor’s Beatles-inspired film Across The Universe, billing it accordingly and crediting John Lennon and Paul McCartney as the songwriters. The problem is, there is no authorized stage adaptation of the film, although there have been intermittent reports that Taymor is contemplating her own, which her attorney affirmed to me. In this case, the Skyline production is still within the statute of limitations for a copyright claim.

That’s where the Skyline scenario gets more complicated – because their “adaptation” of The Wiz wasn’t their only such appropriation of copyrighted material. In 2012, the school produced a stage version of Julie Taymor’s Beatles-inspired film Across The Universe, billing it accordingly and crediting John Lennon and Paul McCartney as the songwriters. The problem is, there is no authorized stage adaptation of the film, although there have been intermittent reports that Taymor is contemplating her own, which her attorney affirmed to me. In this case, the Skyline production is still within the statute of limitations for a copyright claim.

I attempted to contact both the principal of Skyline High and the superintendent of the school district about this subject, ultimately reaching the district’s director of communications Troy Flint. In response to my questions about The Wiz, Flint said, “We believe that we were within our rights. I can’t go into detail because I’m not prepared to discuss our legal strategy. We believe this use was permissible.”

I attempted to contact both the principal of Skyline High and the superintendent of the school district about this subject, ultimately reaching the district’s director of communications Troy Flint. In response to my questions about The Wiz, Flint said, “We believe that we were within our rights. I can’t go into detail because I’m not prepared to discuss our legal strategy. We believe this use was permissible.”

He couldn’t speak to Across The Universe; it seemed that I may have been the first to bring it to the district’s attention. Flint said he didn’t know whether other Skyline productions, such as Hairspray and Dreamgirls, had been done with licenses from rights companies, although I was able to confirm independently that Hairspray was properly licensed. Which raises the question of why standard protocol for licensing productions was followed with some shows and not others.

* * *

My fundamental interest is in seeing vital and successful academic theatre. So while their identities are easily accessible, I’ve avoided naming the teacher, principal and even the superintendent at Skyline because I don’t want to make this one example personal. But I do want to make it an example.

Whether or not I, or anyone, personally agree with the provisions of U.S. copyright law isn’t pertinent to this discussion, and neither is ignorance of the law. The fact is that the people who create work (and their heirs and estates) have the right to control and benefit from that work during the copyright term. Whether the content is found in a published script and score, shared on the internet or transcribed from other media, the laws hold.

If the Skyline examples were the sole violations, a general caution would be unnecessary, but in the past three months alone, Samuel French has discovered 35 unlicensed/unauthorized productions at schools and amateur companies, according to the company’s director of licensing compliance Lori Thimsen. Multiply that out over other rights houses, and over time, and the number is significant. This even happens at the professional level.

At the start, I suggested that students should know the basic of copyright law, both out of respect for those who might make their careers as creative artists, as well as for those who will almost certainly be consumers of copyrighted content throughout their lives. But it occurs to me that these lessons are appropriate for their teachers as well, notwithstanding the current legal stance at Skyline High. There can and should be appreciation for creators’ achievements as well as their rights, and appropriate payment for the use of their work – and those who regularly work with that material should make absolutely certain they know the parameters, to avoid and prevent unwitting, and certainly intentional, violations.

* * *

One final note: some of you may remember Tom Hanks’s Oscar acceptance speech for the film Philadelphia, when he paid tribute to his high school drama teacher for playing a role in his path to success. It might interest you to know that Hanks attended Skyline High and thanks in part to a significant gift from him, the school’s theatre – where the shows in question were performed – was renovated and renamed for that teacher, Rawley Farnsworth, in 2002. Hanks also used the occasion of the Oscars to cite Farnsworth and a high school classmate as examples of gay men who were so instrumental in his personal growth.

I have no doubt that there are other such inspirational teachers and students at Skyline High today, perhaps working in the arts there under constrained budgets and resources. Yet regardless of statutes of limitations, it seems that the Rawley T. Farnsworth Theatre should be a place where respect for and responsibility to artists is taught and practiced, as a fundamental principle – and where students get to perform works as their creators intended, not as knockoffs designed to save money.

* * *

Update, December 3, 2014, 4 pm: This post went live at at approximately 10:30 am EST this morning. I received an e-mail from OUSD’s director of communications Troy Flint at approximately 1 pm asking whether the post was finished and whether he could add to his comments from yesterday. I indicated that the post was live and provided a link, saying that I have updated posts before and would consider an addendum with anything I found to be pertinent. He just called to provide the following statement, which I reproduce in its entirety.

Whatever the legality of the situation at Skyline regarding The Wiz and Across The Universe, the fundamental principle is that we want the students to respect artists’ work and what they put into the product. My understanding is that Skyline’s use of this material is legally defensible, but that’s not the best or highest standard.

As we help our students develop artistically, we want to make sure they have the proper respect and understanding of the work that’s involved with creating a play for the stage or the cinema. So we have spoken with the instructors at Skyline about making sure they follow all the protocols regarding rights and licensing, because we don’t want to be in a position of having the legality of one of our productions questioned as they are now and we don’t want to be perceived as taking advantage of artists unintentionally as we are now. It’s not just a legal issue but an issue of educating students properly.

While everyone I have spoken with about this issue disagrees fairly strenuously with the opinion of the OUSD legal counsel, it’s encouraging that the district wants to stand for artists’ rights and avoid this sort of conflict going forward. I hope they will ultimately teach not only the principle, but the law. As for past practice, I leave that to the lawyers.

Update, December 3, 2014, 7 pm: Following my update with the statement from the school district, I received a statement of response from Bruce Lazarus, executive director of Samuel French. It is excerpted here.

By withholding the proper royalty for The Wiz from the authors, the OUSD is communicating to their students that artistic work is worthless. Is this an appropriate message for any budding artist? That you too can grow up to write a successful musical…only to then have a school district destroy your work and willfully withhold payment?

It needs to be made clear to the OUSD and the students involved that an artist’s livelihood depends on receiving payment for their creative work. This is how artists make a living. How they pay the rent and feed their families. It is simply unbelievable that this issue can be tossed aside with an “Our bad, won’t happen again” response without consideration of payment for their unauthorized taking of another’s property.

Are other students of the OUSD, those that are not artists, being educated to expect payment for their services rendered when they presumably become doctors, engineers, entrepreneurs and the next leaders of the Bay Area? Of course they are. And so it goes for the artists in your classrooms, who should be able to grow up KNOWING there is protection for their future work and a real living wage to be made.

Equal time granted, I leave it the respective parties to resolve the issue of what has already taken place.

October 14th, 2014 § § permalink

Aside from being the month of copious pumpkin flavored foodstuffs, October also brings two perennial theatrical top ten lists that are worthy of note: American Theatre magazine’s list of the most produced plays in Theatre Communications Group theatres for the coming season and Dramatics magazine’s lists of the most produced plays, musicals and one-acts in high school theatre for the prior year. They both say a great deal about the state of theatre in their respective spheres of production, both by what’s listed explicitly, as well as by what doesn’t appear.

In the broadest sense, both lists are startlingly predictable, although for different reasons. If you happen to find a bookie willing to give you odds on predicting the lists, here’s the trick for each: for the American Theatre list, bet heavily on plays which appeared on Broadway, or had acclaimed Off-Broadway runs, in the past year or two. For the Dramatics list, bet heavily on the plays that appeared on the prior year’s list.

But in the interest of learning, let’s unpack each list not quite so reductively.

American Theatre

As I’ve written in the past, what happens in New York theatre is a superb predictor of what will happen in regional theatre in the coming seasons, especially when it comes to plays. Any play that makes it to Broadway, or gets a great New York Times review, is going to grab the attention of regional producers. Throw in Tony nominations, let alone a Tony win – or the Pulitzer – and those are the plays that will quickly crop up on regional theatre schedules.

As I’ve written in the past, what happens in New York theatre is a superb predictor of what will happen in regional theatre in the coming seasons, especially when it comes to plays. Any play that makes it to Broadway, or gets a great New York Times review, is going to grab the attention of regional producers. Throw in Tony nominations, let alone a Tony win – or the Pulitzer – and those are the plays that will quickly crop up on regional theatre schedules.

Anyone who follows the pattern of production would have easily guessed that Christopher Durang’s Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike would proliferate this year, being a thoughtful, literary based comedy with a cast of only six. That American Theatre lists 27 productions doesn’t even take into account the 11 theatres that did the show in 2013-14, and certainly there are non-TCG theatres which are doing the show as well. It’s no surprise that Durang has said he made more money this past year than in any other year of his career; it’s a shame that financial success has taken so long for such a prodigiously gifted writer and teacher.

In general, shows on the American Theatre list have about a three year stay, typically peaking in their second year on the list, but this can vary depending upon when titles are released by licensing houses and agents to regional theatres. 25 years ago (and more significantly years before that) theatres might have had to compete with commercial tours, but play tours are exceedingly rare birds these days, if not extinct.

Perhaps this rush to the familiar and popular and NYC-annointed is disheartening, but it’s worth observing that the American Theatre list notes how many productions each title gets, and that after the first couple of slots, we’re usually looking at plays that are getting 7 or 8 productions in a given season, across TCG’s current universe of 474 member companies (404 of which were included in this year’s figures). Since the magazine notes a universe of 1,876 productions, suddenly 27 stagings of a single show doesn’t seem so dominant after all. Granted, TCG drops Shakespeare from their calculations, but even he only counted for 77 productions of all of his plays across this field. So reading between the lines, the American Theatre list suggests there’s very little unanimity about what’s done at TCG member theatres in any given year, a less quantifiable achievement but an important one.

Perhaps this rush to the familiar and popular and NYC-annointed is disheartening, but it’s worth observing that the American Theatre list notes how many productions each title gets, and that after the first couple of slots, we’re usually looking at plays that are getting 7 or 8 productions in a given season, across TCG’s current universe of 474 member companies (404 of which were included in this year’s figures). Since the magazine notes a universe of 1,876 productions, suddenly 27 stagings of a single show doesn’t seem so dominant after all. Granted, TCG drops Shakespeare from their calculations, but even he only counted for 77 productions of all of his plays across this field. So reading between the lines, the American Theatre list suggests there’s very little unanimity about what’s done at TCG member theatres in any given year, a less quantifiable achievement but an important one.

Dramatics

While titles come and go on the American Theatre list, stasis is the best word to describe the lists of most produced high school plays (it’s somewhat less true for musicals). Nine of the plays on the 2014 list were on the 2013 list; 2014 was topped by John Cariani’s Almost, Maine, followed by A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the two titles were in reverse order the prior year. The other duplicated titles were Our Town, 12 Angry Men (Jurors), You Can’t Take It With You, Romeo and Juliet, The Crucible, Harvey and The Importance of Being Earnest.

While titles come and go on the American Theatre list, stasis is the best word to describe the lists of most produced high school plays (it’s somewhat less true for musicals). Nine of the plays on the 2014 list were on the 2013 list; 2014 was topped by John Cariani’s Almost, Maine, followed by A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the two titles were in reverse order the prior year. The other duplicated titles were Our Town, 12 Angry Men (Jurors), You Can’t Take It With You, Romeo and Juliet, The Crucible, Harvey and The Importance of Being Earnest.

Like the American Theatre list, the Dramatics survey doesn’t cover the entirety of high school theatre production; only those schools that are members of the Educational Theatre Association’s International Thespian Society have the opportunity to participate, representing more than 4,000 high schools out of a universe of 28,500 public, private and parochial secondary schools in the country. Unlike the Dramatics list, there are no hard numbers about how many productions each show receives, so one can only judge relative popularity.

Almost, Maine’s swift ascension to the top rungs of the list is extraordinary, but it’s due in no small part to its construction as a series of thematically linked scenes, originally played by just four actors but easily expandable for casts where actor salaries aren’t an issue. Looking at recent American Theatre lists, they tend to be topped by plays with small casts (Venus in Fur, Red, Good People and The 39 Steps), while the Dramatics list is the reverse, with larger cast plays dominating, in order to be inclusive of more students (though paling next to musicals where casts in school shows might expand to 50 or more).

Almost, Maine’s swift ascension to the top rungs of the list is extraordinary, but it’s due in no small part to its construction as a series of thematically linked scenes, originally played by just four actors but easily expandable for casts where actor salaries aren’t an issue. Looking at recent American Theatre lists, they tend to be topped by plays with small casts (Venus in Fur, Red, Good People and The 39 Steps), while the Dramatics list is the reverse, with larger cast plays dominating, in order to be inclusive of more students (though paling next to musicals where casts in school shows might expand to 50 or more).

The most important trend on the Dramatics list (which has been produced since 1938) is the lack of trends. Though a full assessment of the history of top high school plays would take considerable effort, it’s worth noting that Our Town was on the list not only in 2014 and 2013, but also in 2009, 1999 and 1989; the same is true for You Can’t Take It With You. Other frequently appearing titles are Arsenic and Old Lace, various adaptations of Alice in Wonderland, Harvey, and The Miracle Worker.

No doubt the lack of newer plays with large casts is a significant reason why older classic tend to rule this list; certainly the classic nature of these works and their relative lack of controversial elements play into it as well. But as I watched Sheri Wilner’s play Kingdom City at the La Jolla Playhouse a few weeks ago, in which a drama director is compelled to choose a play from the Dramatics list, I wondered: is the list self-perpetuating? Are there numerous schools that seek what’s mainstream and accepted at other schools, and so do the same plays propagate themselves because administrators see the Dramatics list as having an implied educational seal of approval?

That may well be, and if it’s true, it’s an unfortunate side effect of a quantitative survey. But it’s also worth noting that many of these plays, vintage though they may be, have common themes, chief among them exhortations to march to your own drummer, to matter how out of step you may be to the conventional wisdom. They may be artistic expressions from other eras about the importance of individuality, but in the hands of teachers thinking about more than just placating parents, they are also opportunities to celebrate those among us who may seem different or unique, and for fighting for what you believe in against prevailing sentiment or structures.

* * *

Looking at musicals on the American Theatre list is a challenge, because their list is an aggregate of plays and musicals, and while many regional companies now do a musical or two, it’s much harder for any groundswell to emerge. In the last five years, only three musicals have made it onto the TCG lists, each for one year only: Into The Woods, Spring Awakening and The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee. That doesn’t mean there’s a dearth of musical production, it simply shows that the work is being done by companies outside of the TCG universe.

Musicals are of course a staple of high school theatre, but the top ten lists from Dramatics are somewhat more fluid. While staples like Guys and Dolls, Grease, Once Upon a Mattress, You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown and Little Shop of Horrors maintain their presence, newer musicals arrive every year or two, with works like Seussical, Legally Blonde, Spelling Bee, and Thoroughly Modern Millie appearing frequently in recent years. At the peak spot, after a six-year run, Beauty and the Beast was bested this year by Shrek; as with professional companies, when popular new works are released into the market, they quickly rise to the top. How long they’ll stay is anyone’s guess, but I have little doubt that we’ll one day see Aladdin and Wicked settle in for long tenures.

Musicals are of course a staple of high school theatre, but the top ten lists from Dramatics are somewhat more fluid. While staples like Guys and Dolls, Grease, Once Upon a Mattress, You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown and Little Shop of Horrors maintain their presence, newer musicals arrive every year or two, with works like Seussical, Legally Blonde, Spelling Bee, and Thoroughly Modern Millie appearing frequently in recent years. At the peak spot, after a six-year run, Beauty and the Beast was bested this year by Shrek; as with professional companies, when popular new works are released into the market, they quickly rise to the top. How long they’ll stay is anyone’s guess, but I have little doubt that we’ll one day see Aladdin and Wicked settle in for long tenures.

* * *

When I looked at both the American Theatre and Dramatics lists over a span of time, the distinct predictability of each was troubling. Coming out when they do, before most theatrical production for the next theatre season is set, I’d like to see them looked at not as any manner of affirmation, but as a challenge – whether to professional companies or school schedules. I admire and enjoy the plays that are listed here, and nothing herein should be construed as critical of any of these shows; audiences around the country deserve the opportunity to see them. While I do have the benefit of living in New York and seeing most of these popular shows there, I must confess that I am most intrigued by the theatre companies and school groups that might just say to themselves, ‘Let’s not do the shows, or too many of the shows, that appear on these lists. Let’s find something else.’ Those plays may never appear as part of any aggregation, but I suspect the groups’ work will be all the more interesting for it, benefiting both artists and audiences.

August 18th, 2014 § § permalink

There was a time, children, not so very long ago, when hit plays ran much longer than than 131 performances. Why 131? Because in the last ten complete Broadway seasons, that’s the average of how long a play – new or revival – ran. Yet, out of 313 plays in that decade, only 21 plays ran for 200 performances or more, and only seven ran for 300 performances or more. No play in the past decade topped 800 performances, as The 39 Steps stopped climbing at 794 performances and War Horse headed for the stables at 741.

There was a time, children, not so very long ago, when hit plays ran much longer than than 131 performances. Why 131? Because in the last ten complete Broadway seasons, that’s the average of how long a play – new or revival – ran. Yet, out of 313 plays in that decade, only 21 plays ran for 200 performances or more, and only seven ran for 300 performances or more. No play in the past decade topped 800 performances, as The 39 Steps stopped climbing at 794 performances and War Horse headed for the stables at 741.

Going back 40 years ago, specifically to the 1974-75 season, out of the 42 plays produced on Broadway that year alone, four plays ran over 200 performances, three ran over 400 performances, one ran a hair under 600 performances, and two ran well past 1,000 performances. Those last two plays, FYI, were Same Time Next Year and Equus.

For perspective, a year of performances, assuming 52 weeks at eight shows a week, is 416 performances. So that means in the past 10 years, only five shows ran for more than a year. In 1974-75 alone, four did. What happened?

Well, based on studying the past decade, and then looking at the prior 25 years at five year intervals, it seems the average length of runs for a play hasn’t changed much: from 146 then to 131 now, all of two weeks variance. As Ken Davenport pointed out, new plays run longer than revivals; on average, the difference between them over the past 10 years is about five weeks.

Well, based on studying the past decade, and then looking at the prior 25 years at five year intervals, it seems the average length of runs for a play hasn’t changed much: from 146 then to 131 now, all of two weeks variance. As Ken Davenport pointed out, new plays run longer than revivals; on average, the difference between them over the past 10 years is about five weeks.