April 24th, 2017 § § permalink

According to an old aphorism, “dog bites man” is not big news, however “man bites dog” is something to report. Consequently, in the arts world, “board of directors fires staff” may be of interest, but it’s hardly novel. “Staff fires board of directors” is something else entirely, and that’s what’s playing out right now in Seattle.

Of course, that’s highly reductive, but the fact is, on April 24, the majority of the staff of Theatre Puget Sound, a theatrical service organization for the greater Seattle community, signed a letter to their board which began, “In good faith, we ask you to resign from the TPS Board of Directors. We do this because you have given us reason to have no confidence in your leadership.” It further read, in part:

We stand united to inform you that we will not continue working under your governance. Should you reject this request for your resignation, we will discontinueour employment by May 7.

TPS is now paralyzed by an atmosphere of distrust and organizational dysfunction of your collective making and perpetuation, and only a newly constituted Board of Directors working in full trust, transparency, and partnership with an appropriately supported Executive Director and staff can effectively govern the organization going forward.

This request is made solely with the best interest of Theatre Puget Sound, its mission, and its membership in mind. In the Summer of 2016 you set in motion a cascade of substantial organizational actions, the inevitable consequences of which cannot now be disguised or avoided.

TPS

cannot function without the current staff, but it can and will function without the existing Board.

To date, the TPS board has not resigned, and evidences no intention of doing so.

TPS has been going through a good deal of transition lately. Karen Lane, the organization’s longtime executive director, left her post in November 2016, succeeded on an interim basis by Zhenya Lavy, who had joined TPS in September 2016 as Lane’s deputy. According to a report by Rich Smith in The Stranger, the board asserts that it received a letter from Lavy on April 1, “demanding that they end their search for an executive director, install her in that position, and guarantee her a certain salary. If they don’t meet those demands, then she walks May 5. They have until April 7 to respond.” Per Smith, the board did not agree to the demands and reasserted their intention to conduct a full search.

In Smith’s account, “Lavy paints her ultimatum to the board–that they make her executive director or she leaves May 5 – as a matter of survival…even after working there for a few months, Lavy claims the board hadn’t yet outlined a clear job description for her, nor had they discussed pay commensurate to the task. Because she had been working so much since she started –spending upwards of three nights in arrow sleeping in the office, she says– she’d have to leave the company by May 5 in order to save her health.”

When the staff demanded the board resignation, one employee name was absent, that of Shane Regan, listed on the company website as being in charge of “programs” while identified by Smith in The Stranger as “membership programs associate.” Whatever his title, in the immediate wake of these events, an outpouring of comment on Facebook characterized Regan as the popular, most public face of TPS. Shortly before the letter was sent to the board asking then to resign, Lavy terminated Regan, she says for cause. Rumors swirled that he was fired for refusing to sign the letter, but Regan told Smith that he was never asked to sign the letter.

Smith reported that Lavy was suspended for firing Regan without board approval, but board member Shawn Belyea, who is speaking publicly on behalf of the board, told Arts Integrity that that was not the case. While being careful not to discuss matters that about employees that are legally precluded from being made public, Belyea did not cite Regan’s firing as the cause of her suspension, referring instead to the totality of recent events. He affirmed that the hiring and firing of staff members was within the purview of the executive director.

Because the day of Regan’s firing and the staff letter was also supposed to be the day of a board meeting, Belyea cites the circumstances of the meeting’s cancellation as one reason why Lavy has been suspended, even as he notes that because Regan never signed a termination letter, his status is actually now that of being on vacation. Belyea explained:

Unless it’s stated in the bylaws that you will have x number of public meetings or all your meetings will be public or any of those things, standard practice for non-profits is not public board meetings. Nor would there typically be public notice of the board meeting. So if you go back to Monday there was an announcement put out by the staff on the TPS website that said the board meeting is open to the public. Come to the public board meeting of the TPS board. So that alone constitutes some questionable action. Posting that, then sending out a public notice specifically inviting people from the public to come to the board meeting, that is also a very questionable act.

We had two options in this situation as a board. We have to go to the place where it has been incorrectly posted that the public is invited, where we know from other sources that people have been invited and told that the meeting is public. So we are faced with two choices: we have to go in and tell everybody, no, the board meetings are not public and then close the doors and exclude all these people, or we have to cancel the board meeting and do a separate executive session and start doing some investigation into why these things are happening and what is the agenda of the group that is doing them. All of these things happened on the day of the board meeting, so we did not have a lot of time to respond…

There’s a whole series of actions there that we need to investigate exactly who made those decisions, how those decisions came to be made, what the impact of those decisions are, what the legal ramifications of those decisions are, how these things were communicated to the staff, how these things reflect what the staff believes, what are the staff’s understanding of the situation of their decisions – there’s just a tremendous amount of fact finding that we have to do, partly because none of these actions were taken by the board.

Arts Integrity attempted to reach both Zhenya Lavy and staff member Catherine Blake Smith, identified by The Stranger as “membership and communications specialist,” but received no replies. A Facebook post by by former executive director Karen Lane, cited in The Stranger, backed the call for the board to resign.

In the staff’s resignation request, mention is made of legal counsel advising the staff, which led them to proffer the steps by which the board could resign and a new board take over without jeopardizing the company’s not-for-profit status. Belyea said the board has consulted several attorneys on not-for-profit procedure and human resources procedures, and was also being counseled by Josef Krebs at the consulting firm of Scandiuzzi Krebs, with additional support their City of Seattle liaison at the Seattle Center, where TPS manages multiple rehearsal studios.

Bottom line? It’s a mess. It’s also a very public mess, not simply because of the reporting in The Stranger, but because Lavy sent the request for the board’s resignation to a wide cross section of the Seattle community, including the media, leaders of other arts organizations, community philanthropists and more, and even included a pair of internal e-mails by the board. In addition, Lavy attached the theatre’s whistleblower policy, adopted only at the end of February.

This situation will play out for some time in Seattle. Belyea said the board’s investigation of events was not yet complete when speaking on April 20; a public forum on the situation is scheduled for April 27. It is described as follows on the company Facebook page:

The purpose of this meeting is to dialogue with members concerning recent events at TPS and to provide details regarding the upcoming search for the next Executive Director. Part of this discussion will be for the Board to hear feedback on how best to ensure members are meaningfully involved in the ED search process.

It’s worth noting that with Lavy’s circulation of the whistleblower policy, a flaw in that policy may be exposed. While it seems primarily structured to address issues that arise within the staff, within the board, or between the two, it doesn’t seem to speak to when the two constituencies find themselves in the position of questioning the performance of one another as complete entities. While the policy does allow for circumstances where an executive director’s complaints are lodged against the whole board, in which case they are to consult outside legal counsel, the policy does not suggest that such consultation precipitate the removal of the board. Indeed, the board that has the ultimate legal and fiduciary responsibility for the organization.

The circumstances that led to the brinksmanship at TPS are certainly specific to the organization and the individuals involved, both staff and board. Parsing every gory detail won’t serve the larger national arts community, though The Stranger is on the case for those who want more information, and for future study by arts management educators and students. However, the bird’s eye view of the contretemps should serve as a reminder for boards and executive and senior leadership of arts organizations to examine their practices and policies, because while the situation is rare, it demonstrates how a rapid cascade of events can put an arts organization at risk. That it holds the organization up for public examination, while embarrassing, is not necessarily a problem in and of itself, because it forces the organization to address what have surely been long festering concerns and structural issues.

To be sure, there is crisis at Theatre Puget Sound. As of this writing, the organization’s website lists only two staff members; one week ago it listed five. However, while who has acted properly or improperly, and who has the best interests of TPS at heart – and most likely everyone does, just as everyone probably shares some burden of blame for what evolved – are important questions, certainly a thorough reexamination of the organization’s purpose, structure, leadership and governance is vital. It’s regrettable that it took such an adversarial situation to bring it to the fore.

P.S. While it may now be a footnote in regional theatre lore, in 1976, Adrian Hall, artistic director of Trinity Repertory Theatre in Rhode Island, did essentially fire the theatre’s board when they sought to fire him after a controversial season. He replaced them with a board that supported his artistic vision. But that was 41 years ago, and Hall had personally founded the company. Few have tried it since, or at least few have tried and succeeded.

This post will be updated if the parties concerned respond to Arts Integrity’s prior inquiries, and as events transpire.

An earlier version of this post misspelled Josef Krebs’s first name. It has been corrected above.

October 25th, 2016 § § permalink

In reporting on the dispute between Ars Nova and Howard Kagan, a lead producer of Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812, both The New York Times and the New York Post have seemingly reduced the dispute, at times, to three words or two words, respectively. They’re not wrong about this being triggered by “a mere three words” in the language of the Times report. But there’s really something deeper going on that such diminishment does not fully convey.

For those who have not read about this situation previously, here’s a precis. Ars Nova, a small company well known for staging inventive new works, including not only Great Comet, but Jollyship The Whiz-Bang, Small Mouth Sounds and the current Underground Railroad Game, among others, staged the premiere of Great Comet in 2012. With Howard and Janet Kagan leading the producing team, along with Paula Marie Black, the show transferred to a tent, dubbed Kazino, under the High Line in 2013, later moving to an empty lot on 45th Street near Eighth Avenue. It then was produced at American Repertory Theatre in late 2015 before the current Broadway production began previews at the Imperial Theatre last week, for a mid-November opening.

According to reports, Ars Nova learned two weeks ago that instead of receiving its contractually agreed upon billing on the title page of the Great Comet Playbill, which was to read “the Ars Nova production of,” only their name appeared, as the last in a list of above the title producers, albeit on its own line and immediately before the title of the show. The bulk of the producers were shown in a fairly standard block arrangement, with American Repertory Theatre also afforded its own line after that block, and before Ars Nova. The Kagans appear in first position. The title page also contains language, in much smaller type at the bottom of the page, stating “Originally commissioned, developed, and world premiere produced by Ars Nova,” accompanied by similar language noting ARTS’s contributions.

To date, Howard Kagan and the Great Comet production have issued no statement regarding the billing change, and Ars Nova has only issued a general statement and shared information with the Times. However, the Times report affirms the contractual language that Ars Nova says has been breached, and the company’s managing director, Renee Blinkwolt, says that Kagan began to seek a billing change on October 9, but no such alteration was agreed upon. Press representatives from both Ars Nova and The Great Comet have declined to answer any questions from Arts Integrity.

“The Great Comet” at Kazino in 2013

The implication that this dispute over billing is somehow petty, because it involves only three small words, including “the” and “of,” belies the importance of such a credit to a not-for-profit organization, especially one as small as Ars Nova. While the company may have built a strong reputation in a relatively short period of time, Great Comet is their first show to reach Broadway, and the number of people who will see it nightly will outstrip the number of people who could see any show in their home theatre on 54th Street in a week. This could result in more people taking an interest in seeing work at their home base, in addition to raising their profile in the funding community. Because the current billing now equates them with ART, and denies them a possessory credit, their primary role in fostering and premiering the work is diminished, with any lost impact unknown.

One can only guess at Kagan’s rationale for the unilateral change in the credit. But perhaps given the show’s growth and transformation from Ars Nova to Kazino to ART to Broadway, Kagan feels that the show has developed far beyond what was first seen at Ars Nova, and that with his leadership and financing, it is a transformed production. But ultimately, that doesn’t matter. There is – so far as we know – a contract in force, Kagan was unable to renegotiate it, and neither he nor the current production have the legal right to ignore its terms, regardless of how large or small the alteration.

The Times report included mention of potential legal action by Ars Nova, noting that the theatre’s attorney, “accus[ed] Mr. Kagan personally of breaching his fiduciary duty as an Ars Nova board member by threatening to initiate “a smear campaign in the press in order to irreparably harm Ars Nova’s reputation” as well as by harming its gala.” In a seemingly retaliatory step, the production scheduled its recording session opposite the Ars Nova gala, where the Kagans were to be honored and the Great Comet cast was to perform.

The matter of fiduciary responsibility is not small. While most often thought of as a financial responsibility, the term is really more expansive. According to law.com, a fiduciary is “a person (or a business like a bank or stock brokerage) who has the power and obligation to act for another (often called the beneficiary) under circumstances which require total trust, good faith and honesty.” Board members of corporations, not-for-profit or otherwise, have a fiduciary responsibility to that organization, and it is understood (and often spelled out in writing) that they will operate in that entity’s best interests.

In not-for-profit management, it has become increasingly common for conflict of interest policy to be included in board guidelines, and even for board members to annually sign a disclosure form delineating any possible conflicts of interest. Whether Ars Nova has such a policy or not, the conflict as it is publicly known suggests that by putting any aspect of the commercial production ahead of the interests of Ars Nova, a breach may indeed have occurred.

Howard Kagan is hardly the first board member of a not-for-profit to play a role in taking a production from a company in which they are involved into the commercial arena. Whether as producers or investors, it’s often a matter of pride for board members to participate in the future life of a project. But such relationships require greater scrutiny by the board of directors or trustees (regardless of the term used) to insure such conflicts of interest don’t arise. Even if there is an annual questionnaire, even if it is properly vetted by a board committee empowered to do so, circumstances can arise which change the equation. It is incumbent on board members to disclose even the potential of such situations as they emerge, as well as for boards to seek out such information.

Brittain Ashford and Denée Benton in “The Great Comet” at American Repertory Theatre in 2015 (Photo by Gretjen Helene)

It’s worth noting that this is not unique to board members. In the case of Great Comet, the company’s artistic director, Jason Eagan, is fifth billed on the production, alongside Jenny Steingart, president and co-founder of Ars Nova; Eagan himself is also listed as a board member of the organization. This presents yet another somewhat incestuous relationship between Ars Nova and the Broadway Great Comet, even if it is clear from his public stance that Eagan is clearly acting first and foremost in the interest of defending the company position, rather than the wants or needs of the Broadway run. The Times noted that board members with financial interest in Great Comet were recused from discussion of these issues.

There is also a fiduciary responsibility for the lead producers of Broadway productions, since they have managerial control of the limited liability corporation established to produce any given show. Depending upon the outcome of the current dispute and the legal expenses which accrue to the production, other producers and investors might wonder at the wisdom of the approach that has been taken, since it adds expense that might otherwise have been used to benefit the production, or be returned to those who have a financial interest in the show.

While in Michael Paulson’s Times report, he notes, “The dispute does not affect the financial agreement between the commercial producers and the nonprofit,” that’s somewhat premature. Even with participation in the gross weekly box office receipts, the Times story came out one day after the first preview was performed. No financial distributions would have been made until at least yesterday, and for a show in its first week, even that would be extremely fast. It remains to be seen whether the conflict extends to other contractual terms as well.

This is an evolving situation and hopefully the original contract between Ars Nova and Kagan will be honored, unless the parties come to mutually agreeable new terms. But even if this is all resolved today, it will remain an object lesson for not-for-profit boards and companies about the pitfalls that arise when shows move into commercial production, with key players at the original company taking leadership and financial roles. While it no doubt starts with the best of intentions on everyone’s part, conflicts can arise. Only with disclosure and scrutiny can all parties ultimately come out winners.

Update, October28, 2016: The New York Times reported early this evening that Ars Nova has filed complaints with the American Arbitration Association and the New York State Court over the denial of its contractual billing and Howard Kagan’s breach of fiduciary duty as a member of the board of directors of Ars Nova. It included quotes from a statement by the producer of Great Comet on Broadway:

Ms. Blinkwolt [managing director at Ars Nova] said the two sides had attempted to reach a compromise that would settle the dispute, but those talks broke down.

In a statement, the producers of the show expressed their respect and gratitude for the nonprofit and said they were surprised to hear that the nonprofit had filed suit because they thought the talks were continuing and had made great progress.

The producers said “our understanding is that we are still in discussions. We continue to work toward a swift resolution of this matter for the sake of everyone involved in the show, and we hope that those discussions can continue privately.”

A Facebook post signed by “Jason, Renee and the Gang at Ars Nova,” also posted this evening, read in part:

It has truly taken a village to get The Great Comet to land on Broadway. If you were to remove the contributions of any one partner along the way, we couldn’t be in previews on Broadway today. And yet with no explanation, the proper recognition of our contribution has been taken away. We believe that the show currently on Broadway started at Ars Nova. That it grew and grew and grew until it was a big, beautiful Broadway musical. That narrative – that the show people are seeing on Broadway is, at its core, the show that started at Ars Nova, is extremely valuable to Ars Nova’s past, present and future, and is communicated to the tens of thousands of people seeing The Great Comet on Broadway each week only through our title page billing.

With seemingly no other alternatives to seeking remedy for this lost value, our Board voted unanimously last night to file suit for breach of contract to compel the commercial producers of The Great Comet to honor their contractual obligation to bill the show as “The Ars Nova Production Of.” We are devastated that it has come to this, but steadfast in our belief that the billing we are owed is both valuable and deserved.

This post will be updated as circumstances warrant.

March 27th, 2015 § § permalink

Are you still grumbling about “tweet seats”? Oh, that is so 2013. Time to get with the program and start worrying about the newest development in mobile tech, which could have a vastly more significant impact on the live performing arts.

At this year’s SXSW Festival, a new app, Meerkat, saw a frenzy of adoption by attendees, so much so that Twitter moved to quickly curtail the app’s access to Twitter data. The reason for that draconian move came clearer yesterday when the app Periscope, which is owned by Twitter, was launched as a direct competitor to Meerkat.

At this year’s SXSW Festival, a new app, Meerkat, saw a frenzy of adoption by attendees, so much so that Twitter moved to quickly curtail the app’s access to Twitter data. The reason for that draconian move came clearer yesterday when the app Periscope, which is owned by Twitter, was launched as a direct competitor to Meerkat.

So what do they do? Both apps allow you to stream live video from your phone. Now, instead of taking something so pedestrian as a photograph via Instagram, or so cumbersome as shooting a video and then uploading it to YouTube, anyone with an iPhone and a dream can relay what they’re seeing in real time to their connections on these services. This will of course result in streams from countless teens doing teen oriented things for the entertainment of other teens, but it will also turn everyone who wishes to be into an instant broadcaster into one. Yesterday, Periscope immediately became a source for realtime video of the tragic explosion and fire in New York’s East Village.

Of course, as I experimented with Periscope (I’ve loaded Meerkat, but not tried it yet), I realized how significantly this could have an effect on live entertainment. Now, anyone adept enough at manipulating a smartphone from an audience seat might well be streaming your show, your concert, your opera to their friends and followers. If they can do so with a darkened screen and sufficient circulation to keep the blood from leaving their upraised hand and arm, the only thing stopping them would be vigilant ushers, chastising nearby patrons and battery life. For however long they sustain their stream, your content is on the air – and unlike YouTube, where if you find it, you can seek to have it removed, this is instantaneous and so there’s no taking it back.

I should say that I’m not endorsing this practice, any more than say, a play about graffiti artists is exhorting its audience to go out and start marring buildings with graffiti. I’m just pointing out that there’s a big new step in technology which could serve to let your content leak out into the world in a way that’s much harder to control than before (while also offering many new creative opportunities for communication) – and since these apps are just the first of their kind, they and competing apps will be rolling out ever more effective tools to stream what’s happening right in front of you, just as cell phone cameras and video will continue to improve their quality and versatility.

Scared yet?

Some will quickly say, as they have from the moment cell phones started ringing during soliloquies and operas, that there should be some way to simply jam signals inside entertainment venues. But the answer to that remains the same: private entities like theatre owners cannot employ such technology (which does exist) because they would be breaking the law by interfering with the public airwaves. No matter that the photos, video and streams may be violating copyright. That kind of widespread tampering with communications wouldn’t be allowed – and if it ever were, it could very well have a negative effect on patrons’ willingness to attend.

The quality of streams via these apps would leave much to be desired (think of your stream also capturing the heads of those in front of you, and the couple on your left whispering about their dinner plans). They’d hardly capture the work on stage at its best, but if your choice is $400 a ticket for Fish in the Dark or a free, erratic stream, you just might choose the latter.

The quality of streams via these apps would leave much to be desired (think of your stream also capturing the heads of those in front of you, and the couple on your left whispering about their dinner plans). They’d hardly capture the work on stage at its best, but if your choice is $400 a ticket for Fish in the Dark or a free, erratic stream, you just might choose the latter.

Movie companies have been fighting in-theatre bootlegging since the advent of small video cameras, and one hears stories about advance screenings with ushers continually patrolling the aisles in search of telltale red lights (sometimes wearing night vision goggles) and assorted laser and infrared technologies designed to mar the surreptitious image capturing. But does that seem desirable or even feasible at live theatres?

I’m not shrieking about this problem because I expect plenty of others will. That said, I’m also not about to just instill fear in your hearts and run away. Having just chastised others for enumerating arts problems without offering ideas on how to address them, here’s my thought on how to try to stave off the onslaught of Meerkat and Periscope and their ilk: we have to solve the issues that are preventing U.S. based organizations from cinecasting on the model of NT Live.

Yes, the Metropolitan Opera has built a strong following for their Met Opera Live series. But we’re not seeing that success translate to other performing arts in a significant way, with theatre the most backward of all. I know it may seem counterintuitive, but if people have the opportunity to access high quality, low cost video of stage performances, they’re going to be considerably less interested in cheap live bootlegs in real time. It won’t stop the progression, but it will offer a more appealing alternative.

Video is now in the hands of virtually every person who attends the theatre, the opera, the ballet and so on. Short of frisking or wanding people for phones and having them secured in lockers at every performance space (can you imagine?), the genie is out of the bottle. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not keen on the ramifications of these advances either, but there’s no point in damning reality. The question now is how do the arts respond – by seeking to police its audiences as if attending a performance resembled an ongoing TSA checkpoint, or by offering alternatives that just might make the newest developments unappealing or irrelevant?

But the field, commercial and not-for-profit alike, needs to get a move on, because even if this is the first you’ve heard of Periscope and Meerkat, it won’t be the last. Just wait until smartphones can record and stream in 3D.

P.S. Last week when I saw the Radio City Spring Spectacular, there was a caution against flash photography – not all photography, just flash. There may well have been a warning about video, but all it would have taken was a fake Twitter account and one of these apps to start sharing parts of the show with you as an untraceable scofflaw. Just imagine if I had activated Meerkat a bit sooner.

September 11th, 2013 § § permalink

This afternoon on Twitter, journalists were decrying the proliferation of the word “premiere” in theatres’ marketing and press materials, especially in cases where the usage is parsing a point rather finely or declaring an outright untruth. I feel for Jason Zinoman, Johnny Oleksinski, Charles McNulty, Diep Tran, Kelly Nestruck and their peers, because at times they may have editors wanting them to take note of important distinctions, but don’t necessarily have a complete production history in order to insure accuracy. Having previously explored the obfuscations of arts communication in Decoder and Decoder II (which remain inordinately popular), it falls to me to dissect this phenomenon.

This afternoon on Twitter, journalists were decrying the proliferation of the word “premiere” in theatres’ marketing and press materials, especially in cases where the usage is parsing a point rather finely or declaring an outright untruth. I feel for Jason Zinoman, Johnny Oleksinski, Charles McNulty, Diep Tran, Kelly Nestruck and their peers, because at times they may have editors wanting them to take note of important distinctions, but don’t necessarily have a complete production history in order to insure accuracy. Having previously explored the obfuscations of arts communication in Decoder and Decoder II (which remain inordinately popular), it falls to me to dissect this phenomenon.

How has “premiere” metastasized? World premiere. U.S. premiere. East coast premiere. West Coast premiere. Professional premiere. New York premiere. Broadway premiere. Regional premiere. Area premiere. Local premiere. World premiere production. Shared premiere. Simultaneous premiere. Rolling premiere. I’m sure I’ve missed some (feel free to add them in the comments section).

So what is this all about?

It’s a sign of prestige for a theatre to debut new work, so “world” and “U.S.” premieres have the most currency. This is the sort of thing that gets major donors and philanthropic organizations interested, the sort of thing that can distinguish a company on grant applications and on brochures. You would think it’s clear cut, but you’d be wrong.

If several theatres decide to do a brand new play all in the same season, whether separately or in concert with one another, they all want to grab the “premiere” banner. After all, it hadn’t been produced when they decided to do it, they can only fit it into a certain spot, and they can’t get it exclusively, but why shouldn’t they be able to claim glory (they think). Certainly they’re to be applauded for championing the play, and reciprocal acknowledgment is worthy of note.

But still I imagine: ‘Oh, there was a festival production, or one produced under the AEA showcase code? Well surely that shouldn’t count,’ I can hear some rationalizing. ‘We’re giving it more resources and a longer run. Besides, the authors have done a lot of work on it. Let’s just ignore that production with three weeks of paid audiences and reviews. We’re doing the premiere.’

Frankly, sophisticated funders and professional journalists aren’t fooled. But there are enough press release mills masquerading as arts news websites to insure that the phrase will get out to the public. If anyone asks, torturous explanations aimed at legitimizing the claims are offered. When we get down to “coastal,” “area,” “local” and the like, it’s pretty transparent that the phrase is being shoehorned in to tag onto frayed coattails, but at least those typically have the benefit of being honest in their microcosmic specificity. That said, if multiple theatres, separately or together, champion a new play, they’re to be applauded, and reciprocal acknowledgment is worthy of note.

In the 1980s, regional theatres were being accused of “premiere-itis,” namely that every company wanted to produce a genuine world premiere so that it might share in the author’s royalties on future productions, especially if it traveled on to commercial success. Also, there was funding specifically for brand new plays that was out of reach if you did the second or third production, fueling this dynamic. Many plays were done once and never seen again because of the single-minded pursuit of the virgin work. To give credit where it’s due, that seems less prevalent, even if it has done a great deal to make the word “premiere” immediately suspect. But funders and companies have realized the futility of taking a sink or swim attitude towards new work.

To give one example about how pernicious this was, I was working at a theatre which had legitimately produced the world premiere of a new musical, and the company had been duly credited as such on a handful of subsequent productions. But when the show was selected by a New York not-for-profit company, I was solicited to permit the credit to be changed to something less definitive – and moved away from the title page as is contractually common – lest people think this was the same production and grow ‘confused’. I didn’t relent, but it’s evidence of how theatres want to create the aura of origination.

I completely understand why journalists would be frustrated by this semantic gamesmanship, because they shouldn’t have to fact check press releases, but are being forced to do so. That creates a stressful relationship with press offices, and poor perception of marketing departments, when in some cases the language has been worked out in offices wholly separate from them. Have a little sympathy, folks.

Production history of Will Power’s

Fetch Clay, Make Man

That said, at every level of an organization, truth and accuracy should be prized, not subverted. What’s happening at the contractual level insofar as sharing in revenues is concerned is completely separate than painting an accurate picture of a play’s life (the current New York Theater Workshop Playbill for Fetch Clay, Make Man provides a remarkably detailed and honest delineation of the play’s development and history, by way of example). Taking an Off-Broadway hit from 30 years ago may in fact be its “Broadway debut,” but “premiere” really doesn’t figure any longer, since there’s little that’s primal or primary about it. If you’re based in a small town with no other theatre around for miles, I suppose it’s not wrong to claim that your production of Venus In Fur is the “East Jibroo premiere,” but does anyone really care? It’s likely self-evident.

Let’s face it, any catchphrase that gets overused loses all meaning and even grows tiresome. If fetishizing “premiere” hasn’t yet jumped the shark quite yet, everyone ought to realize that there’s blood in the water.

P.S. Thank you for reading the world premiere of this post.

Thanks to Nella Vera and David Loehr for also participating in the Twitter conversation that prompted this post, which has been recapped via Storify by Jonathan Mandell, including some comments I’d not previously seen.

September 9th, 2013 § § permalink

The Public Works The Tempest

Photo by Joan Marcus

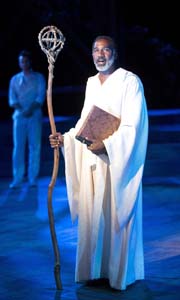

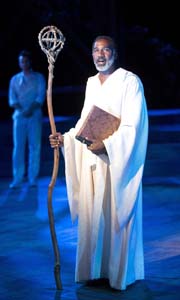

There are many reasons to enthuse about The Public Theatre’s inaugural “Public Works” production of The Tempest – the conception and direction of Lear de Bessonet, the original score by Todd Almond, the perfect weather that blessed each of the three evenings it was on, the enthusiastic performances centered by the Prospero of Norm Lewis. But the greatest achievement was the participation and wrangling of some 200 non-professional performers, rallied in service of a musicalized and summarized version of Shakespeare’s play.

Billed at times as a “community Tempest,” the production utilized, according to a program insert, “106 community ensemble members, 31 gospel choir singers, 1 ASL interpreter, 24 ballet dancers, 3 taxi drivers, 12 Mexican tap dancers, 1 bubble artist (who I must have missed), 10 hip hop dancers, 5 Equity actors (though there were 6 by my count), 6 taiko drummers, 1 guest star appearance (again, I must have missed that, or simply not known the performer), and 5 brass band players.” It was an undertaking of remarkable scale that put me in mind of the deeply moving finale of the New York Philharmonic’s 80th birthday tribute to Stephen Sondheim, when the stage and aisles of Avery Fisher Hall were filled with the bodies and voices of singers uniting for “Sunday,” except that in this case, the large company was present throughout the show and the music was raucous and exuberant.

Christine Lewis & Patrick Mathieu as Alonsa & Gonzalo

Photo by Joan Marcus

The preceding litany of performers accurately suggests that this Tempest was, like Prospero’s isle, full of noises and a wide variety of styles, an at-times almost vaudeville approach to the reworked text, with a wide variety of acts sharing the same stage (I remember the Mexican tappers vividly, though I have already forgotten the pretext under which they were included). But that’s befitting a production which endeavored to engage the New York community not simply by inviting them to watch the production for free, but to participate in it as well. It was also a fitting artistic complement to The Public’s immediately preceding production at the Delacorte, a musical version of Love’s Labour’s Lost.

To be sure, this wasn’t the result of a some lunatic open call. De Bessonet and her team established relationships with specific community groups and performing ensembles and presumably they each rehearsed their segments discretely until the final days when they were assembled en masse. The program for the evening even suggests that in some cases, existing work was incorporated into The Tempest, rather than groups necessarily learning specific material. Sometimes the fragmentary nature was rather obvious (what were those cabbies doing there anyway), but at other times seamless, such as the sequence when a corps of pre-teen ballet dancers wordlessly tormented Stephano, Trinculo and Caliban.

Xavier Pacheco & Atiya Taylor as Ferdinand & Miranda

Photo by Joan Marcus

This manner of artistic engagement with the community isn’t new; the production itself was modeled on a 1915 musicalized Tempest in Harlem with a cast of 2,000. More recently, companies like Cornerstone have gone into specific communities with a handful of professionals to foster the creation of works featuring local non-professionals and there’s probably many a Music Man production which has fielded 76 trombones and more from local schools. But in Manhattan, where community based performance can be overwhelmed in the public consciousness by the sheer volume of professional arts performances, this Tempest was a reminder that a very special and joyous entertainment can emerge from the efforts of those who may not be, nor even desire to be, professional artists.

Clearly this effort was guided by expert professionals and I suspect that its budget far exceeded that of many professional productions seen in New York or around the country. Costuming alone for 200 performers takes some doing, even when many of the clothes may have been borrowed from some of the country’s top regional theatres. Just opening the Delacorte Theatre for rehearsals and performances has real cost. The level of corporate and foundation support behind this Public Works production means this isn’t likely to result in a profusion of comparable efforts.

Norm Lewis as Prospero

Photo by Joan Marcus

That said, the driving concept behind it is worthy of exploration by other groups in other cities and by other coalitions in New York as well. At a time when engagement is both a goal and a buzzword, this Tempest is a high-profile flagship that will hopefully inspire others means of mixing professionals and amateurs, that will prompt more artists to create works that encompass their community, that will even mix up audiences so that the cognoscenti sit alongside proud parents. The production once again affirmed that community theatre is not only valuable but essential, an asset to pro companies rather than a pale imitation of them.

It was also a reminder of the power of collaboration, of the intermingling of different artistic pursuits and organizations to create a blended whole. At a time when the arts are often seen as frivolous or disposable, there is enormous strength in variety and in numbers, sending a message about the essential and broad-based value of creativity and performance at every level of society and life. After all, no one arts group is a magically protected island – they are all part of a vast archipelago, threatened by rising tides that would seek to swamp them.

June 26th, 2013 § § permalink

June 26, 2013

June 26, 2013

President Barack Obama

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue

Washington DC 20500

Dear President Obama:

I realize it’s been a busy week, what with the overturning of the Defense of Marriage Act today and the gutting of the Voting Rights Act yesterday. I know you’ve just begun a weeklong trip to Africa and presumably get home just in time for some fireworks (actual, not political) next week. But we’ve really got to talk about this NEA thing.

I’m referring, of course, to the fact that there hasn’t been a chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts since Rocco Landesman stepped down at the end of your first term. While presumably the agency is running smoothly, the fact remains that for six months now, there’s been no notable public effort to replace him. I know how these things go (I watched The West Wing and House of Cards) and there may be elaborate machinations going on behind the scenes, but without a new chair even proposed, you’re giving off the signal that the arts don’t matter.

A lot of us in the arts know that isn’t true. Since you first took office, we’ve been pleased to see you, the First Lady and your daughters taking in cultural events in New York and in Washington and hosting others at the White House. Some of us would lobby for the symbolism of a cultural excursion by your family taking place outside of the aforementioned cities, or your Chicago hometown, to demonstrate how broadbased the arts community truly is, but the girls have school and you and your wife have countless commitments. We get that. But considering how little attention the previous tenants of your house paid to the arts, I would think that your small personal actions would lead you to action on the big picture.

Sure, I know all about the various government positions you’re trying to fill, including serious problems with stalled judicial appointments, and I don’t want to in any way minimize their import. My god, the whole IRS situation alone must keep you awake at night. However, second terms are when people start peeling away from government appointments, not running towards them, since there’s more than likely a ticking clock on their service, depending upon the preferences of the next president. When Rocco took the NEA gig, he knew he had four years guaranteed, said he only wanted four years, and proved to be a man of his word. His successor might only get three years, even if you act soon.

I know you’re not personally conducting a search or vetting candidates; you have a team of people to do these things and bring names forward for consideration. I’m not presumptuous enough to proffer candidates, especially as my list might be rather theatre-centric, and you may not want to follow Rocco with another theatre-oriented person, since the NEA has an impact on so many areas in the arts. Again, symbolism can be important. Beyond having an advocate in your administration who has the unequivocal authority of the office, we need the affirmation that this is important to you and that you believe the arts are important to the American people. It’s the silence that hurts, especially as we’ve watched the agency diminished over time, albeit with some recent gains that don’t go unnoticed or unappreciated.

Now I don’t know Joan Shikegawa myself, but if the trouble of a search is too onerous and she’s been doing well, then give her the full power. Don’t wait any longer. While we appreciate acting in the arts, “Acting Chairman” diminishes authority, rather than enhancing it. It suggests something transitory, and we need some permanence. We’ve spent too much time over the past couple of decades worrying whether the agency, and federal funding, would even survive.

There are remarkable leaders in the arts, who would be great advocates and great politicians. They would do your administration proud and the arts community could take pride in them. There’s very little the average citizen can do to nudge you on this, although I’m quite certain I could rally the troops on Twitter or Facebook to lob ideas at you via social media. But you probably want more decorum.

Now if it so happens that there’s something we can do, reach out. If there are factors contributing to the delay, give us a sign, so we know where we stand. But what I, and I suspect others, want to know is that the arts aren’t forgotten, and that our president believes they are important enough for his concern, his enthusiasm, and his actions. Name a chairman. Please. I look forward to hearing from you. Not by mail, but in the national news. Soon.

Sincerely,

Howard Sherman

May 3rd, 2013 § § permalink

Going on a theatre binge in a city other than the one in which you reside provides, inevitably, an imbalanced view of that city’s theatrical ecology. Unless you have unlimited time and an unlimited budget, you can barely scratch the surface of all that’s going on, with the possible exception of an intricately strategized Edinburgh visit in August.

For a variety of reasons, both professional and personal (plus free accommodations), I’ve taken to “helicoptering” into London a couple of times a year in an effort to see more than just the work that makes it to U.S. shores, and I’m just back from my spring visit. While it’s undoubtedly by accident, or perhaps a reflection of my own psyche, I was struck on this trip by how seven shows – only one musical; works new and revived; by British and American authors – managed to explore remarkably similar themes. My week was one that focused on looking into the past and the role that honor and integrity plays in our lives.

For a variety of reasons, both professional and personal (plus free accommodations), I’ve taken to “helicoptering” into London a couple of times a year in an effort to see more than just the work that makes it to U.S. shores, and I’m just back from my spring visit. While it’s undoubtedly by accident, or perhaps a reflection of my own psyche, I was struck on this trip by how seven shows – only one musical; works new and revived; by British and American authors – managed to explore remarkably similar themes. My week was one that focused on looking into the past and the role that honor and integrity plays in our lives.

Most obviously, Alan Bennett’s paired one-acts, Hymn and Cocktail Sticks (joined as Untold Stories in a West End transfer from The National Theatre), are autobiography with a decidedly rueful tone. In both cases, Bennett himself (embodied by Alex Jennings) recalls and interacts with his past, focusing on his relationship to music and his father in the former, and his growing intellectual disconnection from his parents in the latter. While Bennett has directly drawn on his own life in the past (he was a key character in his own The Lady In The Van years back), these short plays , written 11 years apart, show him as both reflective and perhaps regretful, a son considering his parents from a vantage point older than they were in the anecdotes on display.

The two most biographical plays (in commercial West End runs), though almost wholly fiction, were Peter Morgan’s The Audience and John Logan’s Peter And Alice. While both are rooted in historical events and real people: the former constructed from the framework of Queen Elizabeth’s weekly audience with the Prime Minister; the latter imagined from a one-time meeting of Peter Llewelyn Davis, the model for J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, and Alice Liddell Hargreaves, the template for Lewis Caroll’s Alice in Wonderland. P&A takes meta to the max, as the adult role models grapple both with the men who gave them potentially eternal life, as well as the characters that bear their name, layering the mortality of humans alongside literary perpetuity, and their memories of their younger selves. The Audience, rather than simply being a highlights reel of postwar British history, uses the weekly audiences instead to address the burden and commitment of being the queen and Logan even allows Her Majesty to interact with her younger self, long since locked away.

The two most biographical plays (in commercial West End runs), though almost wholly fiction, were Peter Morgan’s The Audience and John Logan’s Peter And Alice. While both are rooted in historical events and real people: the former constructed from the framework of Queen Elizabeth’s weekly audience with the Prime Minister; the latter imagined from a one-time meeting of Peter Llewelyn Davis, the model for J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, and Alice Liddell Hargreaves, the template for Lewis Caroll’s Alice in Wonderland. P&A takes meta to the max, as the adult role models grapple both with the men who gave them potentially eternal life, as well as the characters that bear their name, layering the mortality of humans alongside literary perpetuity, and their memories of their younger selves. The Audience, rather than simply being a highlights reel of postwar British history, uses the weekly audiences instead to address the burden and commitment of being the queen and Logan even allows Her Majesty to interact with her younger self, long since locked away.

Just as Queen Elizabeth is bound by the duty of her role, the young man who is at the center of Terence Rattigan’s classic The Winslow Boy (at The Old Vic) is potentially disgraced after an accusation of theft, breaching his family’s honor in the mind of his determined father. Though decades old (it debuted a few years before the Queen was placed in her regal straitjacket), its portrayal of a small cog being tossed aside without due process by a large and ostensibly honor-bound institution has any number of resonances in any era; the senior Winslow, hell-bent on clearing his son’s name, pronounces any number of sentiments that would be welcomed by Occupy Wall Street and veterans’ rights advocates alike. The more obviously political This House (at The National Theatre), set entirely in Britain’s Parliament between 1974 and 1979, though fascinated with the machinations of governing, also turns on tradition and honor, as the legislative body grapples with the place of long-standing practices in the face of political necessity; like The Audience, it takes its framework from history but roots itself in the humanity that manages to stay alive amid conflict that affects an entire country.

Just as Queen Elizabeth is bound by the duty of her role, the young man who is at the center of Terence Rattigan’s classic The Winslow Boy (at The Old Vic) is potentially disgraced after an accusation of theft, breaching his family’s honor in the mind of his determined father. Though decades old (it debuted a few years before the Queen was placed in her regal straitjacket), its portrayal of a small cog being tossed aside without due process by a large and ostensibly honor-bound institution has any number of resonances in any era; the senior Winslow, hell-bent on clearing his son’s name, pronounces any number of sentiments that would be welcomed by Occupy Wall Street and veterans’ rights advocates alike. The more obviously political This House (at The National Theatre), set entirely in Britain’s Parliament between 1974 and 1979, though fascinated with the machinations of governing, also turns on tradition and honor, as the legislative body grapples with the place of long-standing practices in the face of political necessity; like The Audience, it takes its framework from history but roots itself in the humanity that manages to stay alive amid conflict that affects an entire country.

Going further back into history Bruce Norris’ The Low Road (at the Royal Court) posits an amoral antihero plying his capitalist trade in colonial America. With readily apparent parallels to recent economic crises worldwide, Norris deploys as his lead character an apotheosis of financial rapaciousness, looking backwards in order to damn practices of the present day and all too recent past. In this tale, the lack of honor makes the greatest argument for it. The one musical of my visit was a revival of Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along (a West End transfer from the Menier Chocolate Factory), the backwards treading story of three friends irrevocably broken apart at the beginning of the show, only to flash ever backward to the key points of their relationship, like a film run backward as they move from missteps to success to first meetings, and as their superficial, damaged lives are restored to their youthful integrity and dreams.

Going further back into history Bruce Norris’ The Low Road (at the Royal Court) posits an amoral antihero plying his capitalist trade in colonial America. With readily apparent parallels to recent economic crises worldwide, Norris deploys as his lead character an apotheosis of financial rapaciousness, looking backwards in order to damn practices of the present day and all too recent past. In this tale, the lack of honor makes the greatest argument for it. The one musical of my visit was a revival of Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along (a West End transfer from the Menier Chocolate Factory), the backwards treading story of three friends irrevocably broken apart at the beginning of the show, only to flash ever backward to the key points of their relationship, like a film run backward as they move from missteps to success to first meetings, and as their superficial, damaged lives are restored to their youthful integrity and dreams.

So here’s the question: is London theatre consumed by these issues, or do I unwittingly choose shows which embody certain themes? Do I build my own theatrical inkblot? Honestly, I knew little of either the Bennett plays or The Low Road; I saw them because of my interest in those authors. I knew something of the premises of The Audience, This House and Peter And Alice, but no details; I was drawn by the praise of others and by the Helen Mirren and Judi Dench to two of those shows. What if I hadn’t been able to get a ticket to several of these shows? I had only purchased three before arriving in London. What if I had moved beyond the West End and the major subsidized houses into fringe venues, deciding what to see with even less foreknowledge? Perhaps I had curated my own version of PBS’s Masterpiece, cherry picking only the very best of what was on offer and leaving riskier, but perhaps even more compelling and diverse, prospects alone.

So here’s the question: is London theatre consumed by these issues, or do I unwittingly choose shows which embody certain themes? Do I build my own theatrical inkblot? Honestly, I knew little of either the Bennett plays or The Low Road; I saw them because of my interest in those authors. I knew something of the premises of The Audience, This House and Peter And Alice, but no details; I was drawn by the praise of others and by the Helen Mirren and Judi Dench to two of those shows. What if I hadn’t been able to get a ticket to several of these shows? I had only purchased three before arriving in London. What if I had moved beyond the West End and the major subsidized houses into fringe venues, deciding what to see with even less foreknowledge? Perhaps I had curated my own version of PBS’s Masterpiece, cherry picking only the very best of what was on offer and leaving riskier, but perhaps even more compelling and diverse, prospects alone.

Whatever the motivations, intentional or otherwise, I created a week that was informative and reflective, and startlingly consistent in theme even if divergent in style. And for perhaps the only time I can remember, I saw seven consecutive shows and was pleased to have seen each and every one, no mean feat for any avid theatergoer.

But I do wonder: what if I had spiced things up with Viva Forever, or tapped into Top Hat? I would have come away with a markedly different vision of the English stage and its present-day themes. Hmmmm.

March 20th, 2013 § § permalink

Humor me.

In the wake of my post yesterday about the pros and cons of theatre seasons looking like the New York season from the prior year, and some great responses to it, the beloved phrase “national conversation about theatre” keeps coming to mind. Surely you’ve heard this concept, the now decades-old plaint from theatre professionals of all stripes that media conversation can center on a movie, a book, even a song, but that – perhaps not since Angels in America – neither the act of making theatre nor any particular work of theatre has made that grade. Mind you, there are conversations within the field of great value; I’m talking about something that breaks past American Theatre, HowlRound, 2 AM Theatre, Twitter and other resources into the general public consciousness.

This is due to many factors, but surely one is the fragmentary nature of the American theatre. With each company choosing its season independently, there may be coincidences in programming, there may be a handful of select plays dotting the country over the course of a year or two. But in essence, outside of one’s own community, all theatre is a one-off. Perhaps, on occasion, a little – or a lot of – collusion would be a good thing.

By now we’ve all heard of communities that choose a book for a city-wide read, with a concerted effort to promote the idea that a metropolitan bonds if they can all have a conversation about the same thing. This has been going on for a number of years, though not in places where I’ve lived, so I can only admire it from afar, rather than share personal experience. But it is a compelling idea.

Am I now going to suggest everyone should read the same play? No. You’re getting ahead of me. While there’s some merit to that idea, theatre is meant to be seen. I’m thinking bigger.

I wonder whether, say, a dozen theatres, large and small, in different cities and towns, could agree on a single work of theatre (and I’d much prefer that it was a new work, not a classic revival), a play of social and political importance, that could be near-simultaneously produced across the country. Not a tour, not a handful of co-productions, but a whole bunch of theatres doing the same work within, say, an eight-week period.

Now I know that every theatre has to balance its season, struggles with its budget, weighs its logistics. I’m not saying it would be easy. But hear me out.

“Clybourne Park” at Playwrights Horizons

When Clybourne Park was first produced at Playwrights Horizons in 2011, it was followed within weeks by a production at Woolly Mammoth. The following season, it was featured in a number of seasons (as well as in London at the Royal Court), making it to Broadway for the spring and summer of 2012, and now playing in yet more cities in regional productions. Now imagine if all of those productions (sans Broadway, which is irrelevant to my proposal) happened in only a few months time. Think of the conversations that provocative play would have sparked. The same holds true for The Mountaintop, and Good People, and Ruined, and Chad Deity and many others.

A challenge? Yes. Impossible? No. Let us look to history. Specifically, A History of the American Film by Christopher Durang.

“A History of the American Film” at Arena Stage

In 1977, with Durang barely out of the Yale School of Drama, his pastiche of classic movies had a tripartite premiere, with productions in March and April of that year at the Mark Taper in Los Angeles, Arena Stage in DC, and Hartford Stage. It had been discovered in a workshop at The O’Neill the prior summer; it moved to Broadway, briefly, in 1978. But just imagine: a new play, by a tremendously talented up-and-comer, hitting a trifecta of productions out of the gate. I didn’t see it at the time (I was 14), but I sure remember reading about it.

If we want to be part of “the national conversation,” we have to look to a mashup of the Clybourne-History models, so the country will truly sit up and take notice, regardless of whether a New York berth is in the mix or not. We’ll either have to get over our deep desire to proclaim “world premiere” (or agree that everyone gets to say it); we’ll have to use a microtome to slice up the royalties normally given over to an originating company so everyone gets a share, but doesn’t overburden the play’s ongoing life; we’ll have to tacitly accept that the playwright might be working on the piece personally at only one theatre while revisions fly out to many. But remember that thanks to Skype and streaming video, the playwright can confer with disparate teams, and even look in on multiple rehearsals, without criss-crossing the country on planes. And no one need worry about cannibalizing audiences, since city to city overlap is fairly rare.

If many people are seeing the same play at once, we can at last have one show that’s reaching more people in a single night than any individual Broadway or touring show can; we’ll have a story that national press outlets can’t ignore; we’ll have a playwright who can dedicate themselves to working in theatre for a season without receiving an inheritance or a genius grant, since the collective royalties will be significant.

With theatres having just announced or on the verge of announcing their 2013-14 seasons, why do I toss this out for consideration now? Because it would take a year to get this together; for the intra-theatre conversations to begin and bear fruit; for a national sponsor or two to be signed up; for a single advertising campaign to be developed for use by all participants; to insure that a year from now, this grand idea could be unveiled to the public.

Collectively, the number of people who attend theatre on a daily basis in America is significant, but because it’s mostly happening in theatres of perhaps 500 seats or less, its hard for the country at large to get a handle on our significance. So let’s all hang together, since hanging separately doesn’t get us the impact we so desire, so need and so deeply deserve.

Now to find “the” play…

March 19th, 2013 § § permalink

With U.S. theatre seasons being announced almost daily, things have been pretty lively around the old Twitter water cooler, with each successive announcement being immediately met with assessments at every level. How many female playwrights or directors? Is there a range of race and ethnicity among the artists? Is the season safe and predictable or adventurous and enticing? How many new plays, or actual premieres? How many dead writers? How many American playwrights? Any new musicals? The same old Shakespeare plays?

With U.S. theatre seasons being announced almost daily, things have been pretty lively around the old Twitter water cooler, with each successive announcement being immediately met with assessments at every level. How many female playwrights or directors? Is there a range of race and ethnicity among the artists? Is the season safe and predictable or adventurous and enticing? How many new plays, or actual premieres? How many dead writers? How many American playwrights? Any new musicals? The same old Shakespeare plays?

Thanks to social media, what once might have incited some e-mails and calls among friends in the business is now grist for the national mill, and the conversations swing their focus from city to city as rapidly as a new announcement is made. While some of the critiques may strike a more strident tone than I would personally adopt, I have to say that this is evidence of the developing national theatre conscience, under which news of upcoming work is not merely relayed but considered, from a macro rather than micro viewpoint, and not only by artistic directors at conferences or journalists in major media. People are keeping score.

I find this heartening and useful; last year I wrote a column for The Stage in which I declared my belief that the work on U.S. stages must better reflect U.S. society. But even as I applaud every recounting of a season being graded on a variety of balances (gender, race, vintage, etc.), and hope that it informs not only a national conversation but action and change at the local level, I want to strike a note of caution about one of the criteria being applied, specifically: why are so many theatres doing the same plays?

It’s easy if one lives in a major metropolitan area that’s rich in theatre to wonder why certain plays are receiving 10, 15 even 20 productions in a single season, typically works that have been seen in New York, whether on Broadway or off. We all see the list compiled each fall by TCG and American Theatre magazine; it generates stories about the most popular plays at U.S. theatres and usually mirrors the NYC fare of the past year or two. But at the same time, how many new plays remain unproduced, or receive a premiere and then don’t find their way to other stages? Have U.S. theatres become ever more safe and New York-centric?

What seems like a herd mentality has a more practical basis. It has been some time since plays have toured the country with any regularity (before the current War Horse, the last significant non-musical tour I recall was Roundabout’s Twelve Angry Men); the days when a play would run a season on Broadway and then tour for a year are long over. So while not-for-profit theatres may have been born in part to offer an alternative to commercial fare that was once available throughout the country, the life of plays has fallen almost exclusively to institutional companies.

Those companies tend to be fairly hyperlocal, drawing the majority of their audience from a 30 to 45 mile radius. This holds true even for larger cities, although they may benefit from some portion of a tourist trade. Generally, only “destination theatres” like Oregon Shakespeare Festival or Canada’s Stratford and Shaw Festivals can lay claim to a wider geographic spread. So while our overview of production may be all inclusive, the communities being served are less transient and more insular than that view.

On top of that, we can’t deny that theatre in New York has a range of media platforms which, even in our online era, few other cities can match. Consequently, a success in New York, or merely a New York production, gets a boost in the eyes of all concerned – theatre staffs, freelance artists, funders, audiences. And as a result, companies which are the major – or only – theatre in their community may feel duty bound to offer those “name” works in their seasons, because their audiences may not have any other opportunity to see them and also because their artistic leadership believes in the quality and value of that work. Of course, in some markets, theatres may compete for these “name” works, especially if they’re accompanied by the name Tony or Pulitzer.

This was brought home to me years ago during my time as managing director of Geva Theatre in Rochester NY. Geva was by far the largest theatre in Rochester; its peers were the former Studio Arena Theatre in Buffalo, 60 miles to the west, and Syracuse Stage, some 80 miles to the east. Each city had its own theatrical microclimate, with only the smallest sliver of die-hard theatre fans traveling among all three, an effort hampered by a snowfall season that ran from November to April.

Having come from Connecticut theatre, where a daytrip to New York was commonplace for professionals and audience alike, I wasn’t used to working on “last year’s hits” (though Geva’s seasons were certainly much more varied than that). In Connecticut at that time, doing work recently available in NYC was redundant. Frankly, what had been a source of pride at the places I’d worked had become a sign of elitism in my new setting, and I had to adjust my thinking accordingly – a mindset that has stayed with me as I ventured back into Connecticut and then to Manhattan.

This year, Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop has been one of those frequently produced plays; on the east coast alone I know of productions in Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington DC without even looking at schedules; I could just look at the Amtrak Northeast Corridor schedule for that rundown. Some might call this copycatting, especially after its Broadway run the prior season, but based upon reviews and reports of sales, The Mountaintop has been meaningful at each venue where it has appeared, presumably without overlapping audiences. And on a personal note, I have to say that even in a production compromised by a labor dispute, I found the Philadelphia incarnation to be even more affecting than the Broadway one.

Even as I lobby for artistic directors to be ever more committed to a wide range of essential criteria, I acknowledge the difficulty of their task. Aside from taking into account the questions I highlighted in the first paragraph, they also have to consider issues like budget, educational commitments, work that might prove especially meaningful to their audience or their community. Many have to do that with only five or six shows in a given season and it may not be possible to hit every desired mark.

A national survey across a range of criteria will certainly show us trends in production at the country’s institutional theatres, and I avidly support such an effort. But as we look theatre by theatre, we might allow, slightly, for what else could be happening at other theatres in the same city, and perhaps for how each theatre’s season does (or doesn’t) make improvements in diversity year over year. We also have to accept that in meeting one of many goals, a theatre might fall short on another; watching how they trend over time will be the most telling indicator. And while we need more and more platforms for truly new work, if a show with a New York imprimatur is a genuine part of a season striving towards meeting a range of goals, it is not necessarily a cop-out.

A final word for the theatres that face this new scrutiny, from playwright Stephen Spotswood during yesterday’s water cooler chat on Twitter: “Dear theatres whose seasons people are complaining about: This means we care and are invested in you. Start worrying when we stop.”

March 11th, 2013 § § permalink

Nonprofit? Not-for-profit?

Do you have a preference between the two? Do you use them interchangeably? Has your company determined a “house style” for the use of one over the other?

This may seem a semantic game, but I would argue that it is vastly more important than the “er vs. re” argument that rears its head over the spelling of theatre every so often. That silly debate is largely etymological and cultural, while this one is about meaning and understanding.

To get the simplest issue out of the way: hyphens are primarily a style issue. It may stem from the country you live in, or what manual you use as a guide. The hyphen is, basically, irrelevant, at least in regards to meaning.

Legally, there is no real difference between “nonprofit” and “not-for-profit.” Numerous resources confirm that they are essentially interchangeable, save for the Internal Revenue Service. Our friends at the I.R.S. say that “not-for-profit” is an activity which does not undertake to produce revenue, like a hobby, while “nonprofit” is an organization that doesn’t seek to make a profit from its activities, and does not consist of individuals or shareholders who personally benefit from the revenues of the company. You can find helpful descriptions of these terms at Idealist and Grammarist; the Merriam Webster online dictionary is caught in a endless loop, merely defining one as the other.So for organizations’ fine print on fundraising solicitations, since that’s about tax benefits for donations and status with the I.R.S., “nonprofit” appears to be the correct term. But we don’t speak in strict I.R.S. language on a daily basis, and that’s where my interest lies.

Although numerous sources say nonprofit and not-for-profit are interchangeable, I think they carry different connotations. On a purely anecdotal basis, I have arrived at a preference between them; it would be fascinating to test them to see if this bears out.

Over the course of my career, I’ve had a number of occasions where I have been asked to explain what a “non/not-for” company is (for the moment, before I explain my conclusion, I’d like to hedge and call these “N/NF”s). While it has always been second nature to me, and to the people I talk with on a daily basis, it’s actually not something, apparently, that comes up in a lot of people’s education, institutionally or practically. It almost seems anomalous for those working outside of fields where the status is prevalent (social service, health, religion, arts).

My friend Michael, who has an engineering degree, summed up the confusion best when, years ago, he said to me, “So your company can’t make a profit, right? What’s with that?” And that’s where my semantic preference was born, after what was a very lengthy conversation.

While N/NF’s are focused on generating profit, they are not forbidden from ending their fiscal years showing one. Certainly many N/NFs struggle to get out of the red and into the black, but it is hardly unheard of for these organizations to yield a surplus (a more proper term than “profit” in this context). Where they differ from commercial enterprises is that the funds stay within the company; they’re not distributed to partners, workers or shareholders. In fact, when these groups seek funds, donors often like to see that they’ve had a surplus: not so small that it looks like bookkeeping shenanigans, not so large that it looks like they don’t need support or are operating too close to a for-profit mentality.

Consequently, I have developed a strong resistance to “nonprofit,” because it seems to suggest that any company operating under that status is prohibited from showing a surplus. Secondly, I think it also suggests that the organization is the opposite of profitable, which to many businesspeople, would indicate failure. Without profit, how does a business survive? While those who travel in the significant universe of N/NF organizations may have no confusion, those we seek to cultivate and secure as donors may experience significant cognitive dissonance when they encounter “nonprofit business.” To some, it may be an outright oxymoron.

I think that “not-for-profit” suggests a mindset, rather than an operational stricture. It does not seem so hard and fast as to preclude profit or, again, surplus. It intimates that the company has something else on its mind, whether it be fostering the creation of art or assisting those in need. It doesn’t mean we can’t succeed financially beyond breaking even, and that exceeding that goal is wrong; it means that when we do, we use the funds to further the organization’s goals. I think “not-for-profit” is less likely to prompt people to an immediate conclusion, and while it may open up a conversation, that can only be to a company’s benefit.

Yes, perhaps it’s just the English major in me that invests “-for-“ with such meaning, but coupled with my real-life experiences, I’ve come to believe there’s more to it than that. I don’t expect you to just take my word for it; at least have a conversation with the key communicators in your organization about it, test it, make a decision. This may be a question of degree and nuance in the words we choose to speak and write, but to everyone fighting the good fight in not-for-profits, every little advantage helps. Even if that advantage is simply two hyphens and three letters.

P.S. For those in the arts, god save us all from “charitable.”