January 22nd, 2015 § § permalink

An artist’s impression of how the new St Ann’s Warehouse venue will look after its October opening

When the latest incarnation of St Ann’s Warehouse opens in the shadow of Brooklyn Bridge in New York, a theatre that already has a reputation of staging cutting edge UK plays will be in prime position to attract new audiences. Howard Sherman meets its leading lights

There has long been a reciprocity between Broadway and the West End, dating back perhaps a century, with shows and artists travelling back and forth with regularity and acclaim.

For a steady diet of many of the UK’s most acclaimed companies and artists, New Yorkers can turn not only to Times Square but also to an area of Brooklyn called Dumbo (Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass). This is where St Ann’s Warehouse has been a leader not only in presenting provocative, inventive and often thrilling work from the UK, as well as from across Europe, South Africa and Asia, but also at the forefront of the reclamation of an industrial neighbourhood as a community asset.

A wide variety of UK work has played at St Ann’s in recent years, including Kneehigh’s Brief Encounter, The Red Shoes, The Wild Bride and Tristan and Yseult, the National Theatre of Scotland’s Black Watch, several pieces by Daniel Kitson and now Let the Right One In.

Founded by Susan Feldman as Arts at St Ann’s in 1980, the company began with a dual purpose: establishing a creative centre for its Brooklyn Heights neighbourhood while also working to rehabilitate and preserve the historic church building that served as its home. In those days, the company was focused on shortrun concerts and musical events, but its move into the rough and tumble Dumbo neighbourhood in 2001 brought very different opportunities and challenges. From October, it begins work in its fourth venue when it moves into the former Tobacco Warehouse, a short distance from its current interim space, which has been in use since 2012.

Susan Feldman and Andrew Hamingson (Photo by Howard Sherman)

Recalling the early years at the church, Feldman explains how it “lent itself to music and fantastic spectacle”. But, in a move to a Water Street warehouse that was supposed to provide a home for only nine months but lasted for 12 years, theatre moved to the forefront of the programming, somewhat unexpectedly.

“We didn’t build a theatre,” Feldman says. “We used what was there, which was a very interesting grid, plus it had heat, electricity and an alarm system. We just built these temporary structures, so we could be flexible and move the space around. We kept that as we moved from place to place, so that temporary vibe and state of being became permanent.”

With the new building, the company’s executive director, Andrew Hamingson, speaks about only two “revolutionary” changes in store: “For the first time in St Ann’s history, there will be air conditioning, which means we can programme year-round if we want to. The second is a permanent dressing room.”

Hamingson also cites the opportunity for the offices and the theatre to be all under one roof and the increased potential of reaching out to even broader audiences, because the new venue is in Brooklyn Bridge Park, which he says draws 120,000 people each weekend.

While Feldman says St Ann’s audiences have been pretty much split between Manhattan and Brooklyn residents, she and Hamingson say the balance is shifting towards the continually gentrifying Brooklyn. Hamingson notes that they do not have the kind of tourist audience that one finds in Manhattan, but there is a serious international audience that makes its way to Brooklyn. Feldman attributes that to greater awareness of the neighbourhood itself – and to the success of Black Watch in its first of three visits, in 2007, which she calls a “crucial turning point”.

National Theatre of Scotland’s Black Watch

“Black Watch was a very special case,” she says. “There was a big New York Times story about how audiences didn’t want to talk about the war in Afghanistan. Then we did Black Watch and we found people absolutely did want to know about the war. The emotional responses of the audience and the press were so huge that it was more than just a cultural phenomenon. There was a need to wrap your arms around people and that’s what this play was doing and inviting.”

NTS’s executive producer Neil Murray says the show’s run at St Ann’s was significant for NTS as well. “The original run of Black Watch at St Ann’s and Ben Brantley’s New York Times review have been a huge driver not just for that show, but the company’s success in the US. While we have subsequently brought something like another seven shows to the US, including the 2015 runs of Let the Right One In and Dunsinane, that initial Black Watch run was a big springboard.”

The process of bringing a foreign show to the US puts St Ann’s in the position of being a presenter, but also a producing partner. “You can take a show from Europe and it really has to adapt to come over, it has to adapt to come into our space,” says Feldman.

Citing shows like Brief Encounter and Misterman, she speaks of having to shrink the productions. “Recapitalisation has to happen, so that becomes very much like producing. We have to raise money together to close the gap between the presentation costs and the box office. There’s always a period of risk assessment that we go through because we don’t have a single budget every year. We have to develop funding that’s going to go for each project and we put that together the way a producer would for every single presentation.”

St Ann’s does not typically participate financially in the future lives of productions it brings to the US, only doing so in cases where it has commissioned and plans to premiere the work.

Tristan Sturrock in Kneehigh’s Brief Encounter

Kneehigh’s executive producer Paul Crewe says he enjoys Feldman’s risk taking approach, and describes the connection between the companies as one that is “based on the work and a mutual respect”. He adds: “For Kneehigh, St Ann’s was a shop window into the US, because other programmers would often see the work. St Ann’s is one of the reasons we have had opportunities to play other cities and venues in America.”

As for how she finds work, Feldman says she visits three or four festivals each summer and makes trips to London regularly. She says that she also gets recommendations from others in the field.

Hamingson and Feldman say that bringing international work to the US has got harder. There used to be a lot more government funding for cultural exchanges, says Hamingson, adding: “Those pools, because of the downturn, have closed up a bit, so we’ve had to find other partners to take smaller pieces and do more of the fundraising on our own.”

“In fact, we are concerned,” says Feldman, “because there’s a lot of talk in Europe about how they’re going to follow the US model. When they say things like that they mean they’re going to start with philanthropy, but what they’re missing, the one reason that so many people go to Europe to see work is because of the core support that European companies get in their towns and in their cities.

“That support sustains the development of work on a regular basis. If it goes away, because they want to go on the US model, there is going to be an even worse drying up of original work. To me, it’s not a great sign. On the other hand, for European companies to be able to make use of philanthropy, and the desire of patrons to support, is a good thing for sure.”

As for the distinction between Brooklyn and Manhattan, neither Crewe nor Murray place much emphasis on it back home. “People in the UK are certainly aware of St Ann’s particular kind of programming,” says Murray. “I don’t think it’s a coincidence that companies we really admire, like Kneehigh and Druid, are also frequent visitors there. I’m not sure a Scottish audience makes that distinction between Manhattan and Brooklyn, but in deference to Susan Feldman, we are always very careful to differentiate.”

“We have had, and continue to have, an interest in Manhattan,” says Crewe. “But the fact that St Ann’s is slightly outside the Broadway and Off-Broadway aesthetic gives us a sense of being part of a maverick world – an outsider that is a little rebellious. This fits well with us.” St Ann’s move into the new Tobacco Warehouse facility this year will be followed by the openings of several new performing arts venues, including the Ground Zero Arts Center, the Culture Shed, and Pier55. So is Feldman concerned about market saturation? Not really: “You know, the more culture there is, the more culture there is.

“What’s really going to determine what goes into those buildings as well as what goes into our building is going to be the financial relationships of whatever’s going in there. They’re not going to be the Metropolitan Opera suddenly that’s got an unlimited budget to make art. Five spaces the size of St Ann’s, which is what the Shed is supposed to be? I don’t know. But they’re talking about Fashion Week, they’re not talking about Mark Rylance and Measure for Measure. Some people say we’re all competing for the same money and it’s going to be a very competitive. I don’t think we’ve ever competed on that level, so I’m not sure. We’ve always been a niche.”

* * *

5 things you need to know about St Ann’s

* Founded 1980 in a historic landmark church by the New York Landmarks Conservancy to provide a complementary public use for the building and to preserve the first stained glass windows made in America.

* It has never had a permanent home. This will only come with the opening at the Tobacco Warehouse in October 2015.

* St Ann’s Warehouse has been the New York base and often national launching point for multiple theatre pieces by the National Theatre

of Scotland (Black Watch and Let the Right One In); Enda Walsh (four productions including Misterman); Kneehigh (four productions including Brief Encounter and The Wild Bride; and Daniel Kitson (including the world premiere of Analog.ue), among others.

* St Ann’s activated the first warehouse at 38 Water Street in DUMBO in November 2001, one month after 9/11, with a sold-out concert hosted by Martin Scorsese.

* American rockers who have also found an artistic home at St Ann’s include Lou Reed and Jeff Buckley.

* * *

This article reflects British spelling and the copyediting style of The Stage, where it first appeared.

December 21st, 2014 § § permalink

Ari Roth

I have never attended Theater J in Washington DC. I have become increasingly aware of its work as controversy over that work has risen in recent years, while at the same time I have become aware of the high regard in which the company and its longtime artistic director, Ari Roth, are held by many theatre professionals I admire and call my friends. That Roth was fired this week after nearly two decades is simultaneously shocking and wholly unsurprising, as the theatre seems to have been on a collision course with the Washington DC Jewish Community Center, of which Theater J is a resident program (as opposed to a tenant), for some time over work that some in the Jewish community perceived as anti-Israel and therefore not deserving of a place in a JCC.

I cannot judge the work itself, because I have neither seen nor read it. I cannot be seen as impartial, at least by some, because I am a theatre professional who regularly speaks out against censorship, and because I am a Jew who does not believe that my religion requires unquestioning support of the State of Israel and its political, social and military policies. I do believe in the importance of Israel for the Jewish people and its right to exist, but I also believe in the rights of Palestinians to their own homeland as well, and the right and necessity of both populations to live in peace.

So rather than opine at length, I choose to share with you excerpts from many stories about Theater J, with links to the full reports, which in turn link to yet more. I decry the pressure that Theater J has been subjected to and the manner of Ari Roth’s firing. I believe that Roth’s artistic vision will ultimately be best served at his planned new company Mosaic Theater Company – a name I love for its ability to invoke both the Moses of biblical times, as well as the ancient art form of arranging multi-colored tiles to create art, suggesting the coming together of many fragments to make a larger and more cohesive whole. As for what happens to Theater J now, I hope it doesn’t become a home for only feel-good Jewish stories, but manages to sustain itself as a place that challenges those who attend and fosters debate among them, characteristics that I was taught from a very early age were a central part of Judaism.

From “Theater J incident illustrates larger dialogue on Israel at Jewish institutions” by Peter Marks in The Washington Post, August 6, 2011:

Andy Shallal, an Iraqi-born Muslim, was deeply proud of the open conversation channel he had maintained with Ari Roth, longtime artistic director of Theater J, a highly regarded branch of the D.C. Jewish Community Center. Together with another local theater lover, Mimi Conway, they’d created the Peace Cafe, an after-play forum, complete with plates of hummus and pita bread supplied by Shallal’s popular Busboys and Poets dining spots, that had become a mainstay of Theater J’s programming.

The makeshift cafe — established 10 years ago, during the run of a politically charged solo play about the Mideast by David Hare — has been important as an outlet for debate over issues raised in Theater J’s sometimes provocative repertory, especially for an outsider such as Shallal. “It was an emotional experience for me, to walk into a Jewish community center, to grow up as a Muslim, thinking of Israelis as really scary people,” he says. “I walked through that door, and it was a very beautiful experience.”

Then, suddenly, a few months ago, a curtain was drawn. The community center’s then-chief executive officer, Arna Meyer Mickelson, told Shallal that the Peace Cafe could no longer use the facilities of the center, at 16th and Q streets NW. “She said, ‘We appreciate what you’ve done, but we can’t have Peace Cafes at Theater J anymore,’ ” Shallal recalls. “I think she was waiting for the right moment to cut the strings.”

From “Heated Dialogue, Onstage and Off, at Theater J” by Lonnie Firestone in American Theatre magazine, February 2012

Maybe it’s the temperature, maybe it’s the politics—but there’s something about plays from the Middle East. Ask Ari Roth, artistic director of Theater J in Washington, D.C., who has produced more plays from that region than any other theatre artist in America. Roth can attest that the dialogue in plays from this part of the world is “more scalding than subtle. But that’s good, arresting theatre.”

Heated dialogue has become a Theater J trademark, both during the plays and at post-show talkbacks. A focus on Israel and the Middle East is one surefire way to attract passionate audiences (and occasional detractors). Since taking the helm of Theater J in 1998, Roth has been as avid about producing work that engages with Israeli life, culture and politics as he has about producing plays about American Jewish life.

From “Where do Jewish federations draw the ‘red line’ on opinions about Israel?” by Jason Kamaras on JNS.org, September 23, 2013:

Ari Roth, artistic director of Theater J, told JNS.org that “The Admission” is all based on “actual research done by three historians,” rather than implying the “fictitious 1948 massacre” that Young Israel’s Levi described in his letter. “The Admission” was also featured in an April 2013 workshop that was underwritten by the Israeli Consulate of New York, which Roth called an Israeli “hechsher” on the play.

COPMA does not acknowledge Theater J’s slate of more than 35 plays and workshops relating to Israel over the last 16 years, said Roth, who among other plays the group has performed cited “Dai” (“Enough”), which details the experiences of 14 different Israelis in the moments before a suicide bombing.

Theater J also never actually produced “Seven Jewish Children,” explained Roth. Instead, the group held a “critical dissection” of the play, featuring readings of “Seven Jewish Children” and response plays, as well as a talk to start the event that included “what troubled me about the play,” Roth said.

The DC federation, in an April 2011 statement, said it would not fund “any organization that encourages boycott of, divestment from, or sanctions against the State of Israel in pursuit of goals to isolate and delegitimize the Jewish State.” Theater J “stands squarely” against the BDS movement, Roth told JNS.org.

“We are all about bringing Israeli art over here, engaging with Israel,” he said. “We are a leading importer of Israeli cultural talent to Washington.”

Hanna Eady, Elizabeth Anne Jernigan, Leila Buck, Danny Gavigan, Pomme Koch, Kimberly Schraf, and Michael Tolaydo in The Admission (Photo by C. Stanley Photography)

From “Theater J Scales Back Show as Pro-Israel Critics Pressure Washington D.C. Troupe” by Nathan Guttman in the Jewish Daily Forward, October 9, 2013:

In an apparent bow to the right in the Jewish culture wars, Theater J, a celebrated theatrical group housed at Washington’s DC Jewish Community Center, will not produce a play set to open this spring that has been denounced by critics as anti-Israel.

The troupe will instead run a workshop on the play and a moderated discussion. . .

The compromise reached between Theater J and the DCJCC will likely not put an end to the heated political debate about the play. Activists from a group called Citizens Opposed to Propaganda Masquerading as Art, which organized the pressure campaign, have made clear they will not discuss anything short of removing the play altogether. The group’s chairman, Robert Samet, told the Forward earlier that he would accept only the play’s cancellation.

Carole Zawatsky, CEO of the DCJCC, told the Forward that the decision to cancel the full production was not a result of the outside pressure. “This had nothing to do with COPMA,” she said. “COPMA is trying to shut down the conversation and we are trying to broaden it.”

The DCJCC explained the decision as stemming from their “guiding principle” that plays from Israel should be done in partnership with Israeli theater companies. And since a planned partnership did not materialize, Theater J will not present a full production in Washington. The workshop, Zawatsky said, will include the play’s author, Motti Lerner, alongside other historians, artists and political figures.

The controversy surrounding production of The Admission is only the latest in a series of attacks against the capital city’s Jewish theater company involving plays related to Israel. Theater J rejected the earlier rounds of criticism, insisting on its right to stage the plays in question as a matter of artistic freedom.

This time, however, the debate was deepened by a call from the theater’s detractors to withhold donations from the city’s Jewish federation because of its support for the artistic group.

From a letter by The Dramatists Guild and the Dramatists Legal Defense Fund to the Jewish Federation of Greater Washington and the DC JCC, January 27, 2014:

We understand that a group that calls itself Citizens Opposed to Propaganda Masquerading as Art has been formed to discourage Theatre J’s production of The Admission by advocating a boycott of your organizations and other intimidating tactics. Yes, private citizens have a right to object to the plays you produce by not funding you, and no, their actions do not constitute “censorship” in the strictest sense, but the bullying tactics of this group in order to impose their political worldview on the choice of plays you present must not succeed. As the representative of writers of all political persuasions, religious beliefs, etc., the Dramatists Guild strongly opposes their actions and agenda.

We find it ironic that COPMA’s wish to stifle the play is purportedly in defense of Israel, yet the Israeli minister of Home Security himself has said: “In the past, some plays by Motti Lerner have created stormed discourse … This discourse is taking place in the public sphere and that is where it should be. The State of Israel is proud of the freedom of expression in the arts in it and especially the freedom of expression in the theater.”

Should the Jewish Federation of Greater Washington and the DCJCC have a lower standard for the freedom of expression than Israel? Surely if a state under siege since its founding can withstand criticism in the form of drama, so can your audiences.

From “For Jewish groups, a stand-off between open debate and support of Israel” by Marc Fisher in The Washington Post,” May 28, 2014:

The D.C. Jewish Community Center runs a popular music festival featuring klezmer, a cappella, Broadway, liturgical and classical sounds. This year, they invited a Brooklyn feminist punk rock band called The Shondes — Yiddish for “disgrace” — to join the lineup.

Weeks later, the center uninvited The Shondes because the band’s leader had made public statements questioning whether Israel should exist as a Jewish state.

The JCC has staged an “Embracing Democracy” series over the past year, tackling tough issues with speakers on American Jews’ relationship with Israel and the birth of the Jewish state. David Harris-Gershon was asked to speak on his memoir about how he changed after a Palestinian terrorist’s bomb in Jerusalem seriously injured his wife.

But the JCC withdrew Harris-Gershon’s invitation after discovering that he had written a blog post sympathetic to the boycott and divestment movement against Israel. . .

“A wonderful aspect of Jewish tradition is healthy debate,” says Stuart Weinblatt, rabbi at Congregation B’nai Tzedek in Potomac, Md. “But ultimately, a big tent does have parameters. It’s not inappropriate for the JCC or any institution to ask, ‘Does this play or speaker convey a narrative that helps people understand Israel’s ongoing struggle?’ There are plenty of venues willing to host productions critical of Israel. The Jewish community doesn’t need to be that place.”

“You have to push the envelope, you have to challenge,” says Gil Steinlauf, senior rabbi at Adas Israel Congregation in the District. “This is the essence of what it means to be Jewish: We welcome dissent. And I do see a move away from that welcome in the Jewish community.”

From “DCJCC Cancels Theater J’s Middle East Festival, Prompting Censorship Debate” by Nathan Guttman in the Jewish Daily Forward, November 25, 2014:

Theater J, a nationally acclaimed group under the auspices of the Washington DC Jewish Community Center, is battling a decision by the JCC to cancel its annual Voices From a Changing Middle East Festival. The theatrical festival, which in the past has included works critical of Israeli policy, was asked to accept a rigorous vetting process of artists this year to limit that criticism.

“Increasingly, Theater J is being kept from programming as freely, as fiercely, and expressing itself as fully as it needs,” the artistic director, Ari Roth, wrote to the company’s executive committee in September, in an internal document obtained by the Forward. “We find the culture of open discourse and dissent within our Jewish Community Center to be evaporating.”

Theater J and the DCJCC are not the only institutions caught between donors concerned about negative depictions of Israel and creators arguing for artistic freedom; New York City’s Metropolitan Opera is still reeling from the protests against its decision to produce “The Death of Klinghoffer”; the JCC in Manhattan came under fire in 2011 for partnering with progressive organizations, and in San Francisco, the Jewish film festival was the first, in 2009, to face pressure from donors to change its programming.

“It’s pervasive,” said Elise Bernhardt, former president and CEO of the now-defunct Foundation for Jewish Culture. “At the end of the day, they are shooting themselves in the foot.” Bernhardt said that attempts to censor Jewish art will only deter young members from being involved in the community.

From an e-mail sent by DCJCC Executive Director Carole Zawatsky to the DC JCC board on December 18, 2014:

I am writing to let you know that Ari Roth will be stepping down as the Artistic Director of Theater J. Ari has been a great leader of our theater program for the last 18 years and has grown Theater J into an award-winning and groundbreaking destination for our community. Under his guidance, Theater J has become the premier Jewish theater in the country and has gained national critical acclaim. We are so proud of the heights we have reached with Ari at the helm. While Ari will no longer be the Artistic Director of Theater J, we have offered Ari the opportunity to continue to curate the Voices From a Changing Middle East Festival and use its branding wherever his next endeavor shall be.

To all the people who have worked most closely with Ari to make Theater J the incredible success it is today, I want to assure you of our continued commitment to Theater J’s mission of presenting thought-provoking, engaging theater. While a search is underway for a new Artistic Director, Theater J will continue operating under the leadership of two people you already know well: Managing Director Rebecca Ende and now Associate Artistic Director Shirley Serotsky.

From “Artistic director Ari Roth is fired from Theater J” by Peter Marks in The Washington Post on December 18, 2014:

Ari Roth, longtime artistic director of Theater J, an organization he has built over the past 18 years into one of the city’s most artistically probing and ambitious theater companies, said he was fired Thursday. Roth said notice of his dismissal was delivered by Carole R. Zawatsky, chief executive officer of the DC Jewish Community Center, of which Theater J is an arm. The cause given, he said, was insubordination, violating what he called the JCC’s “communications protocol.”. . .

On Thursday night, the DCJCC released a statement quoting Zawatsky as saying: “Ari Roth has had an incredible 18-year tenure leading Theater J, and we know there will be great opportunities ahead for him. Ari leaves us with a vibrant theater that will continue to thrive.”

Roth and Zawatsky, who was hired by the JCC in 2011, clashed repeatedly over some of Roth’s programming choices, particularly as they concerned the Middle East. Earlier this year, Theater J’s world premiere of “The Admission,” a play by Israeli dramatist Motti Lerner about a purported massacre of Palestinian villagers in 1948 by Israeli soldiers, was downgraded by the center from a full production to a workshop. That occurred after a small local activist group’s campaign to stop the play asked donors to withhold funds from the JCC’s parent body.

The group, calling itself Citizens Opposed to Propaganda Masquerading as Art, launched a similar effort in protest of a Theater J offering in 2011, “Return to Haifa,” a play that featured Arab and Israeli actors. From the highly regarded Cameri Theatre of Tel Aviv, Boaz Gaon’s drama — adapted from a novella by a spokesman for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, later assassinated — portrayed a Palestinian family returning to the home it had fled in 1948 that was occupied by Israeli Jews.

The latest and apparently final dispute was over the fate of Theater J’s Voices From a Changing Middle East Festival, an ongoing series of which “Return to Haifa” and “The Admission” were a part. Last month, the Jewish Daily Forward reported that the DCJCC was eliminating iterations of the festival. Roth said his commenting to the media after the article appeared was the reason given to support the charge of insubordination.

From “Ari Roth’s Firing From Theater J Is Part of a Larger Conflict About Jewish Criticism of Israel” by Benjamin Freed in the Washingtonian on December 19, 2014:

But the aggressive pushback that Israel’s critics like Roth and Judis from their fellow Jews isn’t a recent phenomeon, says Alan Elsner, the vice president of communications for J Street, a left-wing Middle East policy organization that calls itself pro-Israel and pro-peace. The group was founded in 2008 because the subject of Israel “had become so toxic that institutions, people, synagogues felt they couldn’t discuss it intelligently anymore,” he says.

Elsner believes the loud, hawkish voices that attack people like Roth are a slim portion of the the American Jewish community, but they do include some wealthy donors flexing their political clout. But those reactions, Elsner says, come at the expense of the Jewish population’s future.

“It’s a formula for driving away young people, driving away people who love Israel, but are not supportive of the settlements, and see the current government destroying the country,” he says. “The right has been in power in Israel with short breaks since 1977, and they’ve pursued building settlements and had three or four wars. The problem is, how do American Jews who support Israel and love Israel engage in a meaningful dialogue with Israel without being cast out of the tent?”

From “Ari Roth’s swift departure from Theater J follows a tumultuous tenure” by Peter Marks in The Washington Post, December 19, 2014:

As Ari Roth, Theater J’s longtime artistic director, recalled it, he sat down over a couple of lunches with Rabbi Bruce Lustig of the Washington Hebrew Congregation and the JCC’s chief executive, Carole R. Zawatsky, in an effort to undo the ire and mistrust that had soured his dealings with his boss.

“We went to marriage counseling,” is how Roth wryly describes those attempts. “We worked on our relationship.”

The meetings apparently came to naught, for on Thursday, Roth was fired by Zawatsky from the job he had held for 18 years, a tenure during which he built Theater J into one of the leading Jewish theaters in the country and one of the most important outposts for plays about Israel and its neighbors. His termination came after he refused to sign a severance agreement that would have given him six months’ salary and required that he keep quiet about the nature of his exit.

The firing, which was greeted with expressions of disbelief and widespread condemnation by everyone from Washington actors, directors and artistic directors to playwright Tony Kushner, was in point of fact the culminating event of a difficult, years-long struggle between Roth’s company and those in charge of the august Jewish institution on 16th and Q streets NW that housed it. Furious over some of his programming decisions — including producing a play based on a novel by a onetime spokesman for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), and a staged reading of another playlet, Caryl Churchill’s “Seven Jewish Children,” labeled by some as anti-Semitic — activist groups and others had exerted pressure on the JCC to try to stop them.

The dismissal, though, was not merely the wrenching end to a long-simmering personnel matter involving a headstrong staffer. It was also an illustration of a growing rift in the Jewish community, over what kinds of dialogue concerning Israel can be tolerated at a multipurpose Jewish organization — and whether, in fact, programming perceived as critical of Israeli policies has any place at a center for Jewish culture.

“The work that Ari’s been doing isn’t more or less controversial than it was 10 years ago, but the atmosphere for airing different voices has changed,” said Joshua Ford, who was the DCJCC’s associate executive director until leaving in March. “That’s in part because there’s a perception that Israel is more besieged than ever, and that’s a perception with some reality to it. And part of it is that it’s very, very hard for artists and institutions just to get along in general.

“Artists need to be artists,” Ford added, “and institutions need to answer to more than just their artistic impulses.”

From “Ari Roth, Director of Jewish Theater, Is Fired” by Michael Paulson in The New York Times, December 19, 2014:

Under Mr. Roth’s leadership, Theater J has periodically produced work that has tested the Jewish Community Center. This year, the agency scaled back a production of “The Admission,” which depicted a disputed incident of Israeli soldiers killing Palestinians in 1948, and canceled a Middle East festival; in 2010 the theater scuttled a production of a play about Bernie Madoff after objections from Elie Wiesel, the Holocaust survivor and writer; in 2009 there was controversy over a play by Caryl Churchill that some saw as anti-Semitic.

Mr. Roth said he was fired after unsuccessful efforts to negotiate an agreement to allow him to do some of his most contested work as a freelancer, or to make Theater J, which is producing six shows this season and has a $1.6 million budget, financially independent from the Jewish Community Center. He said he had recently been reprimanded for speaking to the news media without permission, and that he believed the J.C.C. wanted him gone to eliminate a possible source of concern for donors during a coming capital campaign.

“This was a long time coming, but it was becoming clear that for the theater to fully express itself, not just on the Middle East but on a whole range of issues, there was a growing artistic impasse,” he said.

Tony Kushner’s The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide… at Theater J

At the conclusion of Friday’s evening’s performance at Theater J, the following statement from playwright Tony Kushner was shared with the audience, read by members of the company of Kushner’s The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures, Theater J’s current production:

We know it’s been a long evening of theater, but we’d like to take one more moment of your time. We wouldn’t be standing here tonight without the hard work and fierce dedication of our friend and colleague, the artistic director of Theater J, Ari Roth. Yesterday, Ari was fired by the CEO of the Washington, D.C. Jewish Community Center in consultation with the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees of this center. This decision is of grave concern to theater artists and audiences alike. Ari wasn’t fired, as the executive committee has claimed, because of ‘insubordination.’ That is a preposterous and cowardly whitewashing of the truth. Ari was fired because he believes that a theater company with a mission to explore Jewish themes and issues cannot acquiesce to demands for an uncritical acceptance of the positions of the Israeli government regarding the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, or to an insistence on silence. Ari was fired because he refused to surrender to censorship; he was fired because he believes that freedom of speech and freedom of expression are both American values and Jewish values. “The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide” has 3 more performances. We can’t continue without expressing our shock and dismay at this violation of principles we cherish. Theater artists and administrators across the country are already speaking out in protest. We join them, and we hope you’ll join us. We call on the full Board of the DCJCC to renounce the action its executive committee has taken, and by renouncing it, demonstrate its support for theater that engages with contemporary reality in all its complexity, free of the fear of censors. Thanks for listening, thanks for being a great audience, and Ari, thanks for everything–shabat shalom, Godspeed, and good night.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BqTCWWaH7r0

In a New York Times Magazine article, “Can Liberal Zionists Count On Hillary Clinton?” published on Sunday, December 21, 2014 and wholly unrelated to the firing of Ari Roth at Theater J, one paragraph struck me as particularly apt to the themes and reality surrounding the theater and its place in discourse about Israel and the Middle East, echoing the observations of others:

“In many segments of American Jewry,” Zemel said, “one is free to disagree with the president of the United States, but the prime minister of Israel is sacrosanct. How patently absurd!” Zemel’s criticism of the current Israeli government pivoted to a discussion of how the Holocaust and that summer’s flare-ups of anti-Semitism in Europe reminded them all that Israel was existentially necessary. “We must love Israel even harder,” he concluded, quoting from the Israeli national anthem. “Od lo avda tikvateinu. We have not yet lost our hope.”

From “An Interview With Former Theater J Artistic Director Ari Roth” on HowlRound.com, December 21, 2014:

If you look around the country, how many plays are there on an annual basis that touch on the Middle East conflict? And then you think it’s such a rich source of drama and there are so many talented people writing about it, why aren’t they touching this subject? I don’t think they should use my example as a cautionary tale, they should use my example as a reason to do more of it. I shouldn’t be one of the only TCG theater artists engaged in this issue. It’s inexplicable to me that we don’t have a dozen other theater companies engaging in this theater subject. It isn’t the third rail, it isn’t that volatile or lethal. There’s not that much paranoid Jewish money that is so concerned about this issue being voiced. I think artists ask themselves how much do they know, how much more could they learn about the conflict and what’s my responsibility to reflect that on our stage? A lot of people could be doing this work and should be.

Via Twitter, a final observation from The Washington Post’s Peter Marks:

* * *

Update, December 22, 2014, 1 pm: The artistic directors of a broad cross-section of U.S. theatres have sent a letter regarding Ari Roth’s firing to the Board of Directors of the Washington Jewish Community Center. It reads:

We, the undersigned Artistic Directors, are outraged by the action of the JCC in Washington DC in summarily dismissing the long-serving Artistic Director of Theater J, Ari Roth, on the morning of December 18.

The stated cause was ‘insubordination’, and it is absolutely clear that Roth was fired because of the content of the work he has so thoughtfully and ably championed for the last two decades.

Ari Roth is a capable, brilliant and inspiring leader of the American non-profit theater. The actions of the JCC, in terminating him for blatantly political reasons, violate the principles of artistic freedom and free expression that have been at the heart of the non-profit theater movement for over half a century. Such actions undermine the freedom of us all.

A free people need a free art; debate, dissent, and conflict are at the heart of what makes theater work, and what makes democracy possible. We deplore the actions of the JCC, offer our complete support for Ari Roth, urge the American theater community to protest these events in all possible ways, and call upon the full Board of the JCC to renounce this action of the Executive Committee of the JCC.

Update, December 28, 2014 11 am:

From “D.C. Jewish Community Center head details ‘insubordination’ of Ari Roth” by Peter Marks in The Washington Post, December 26, 2014:

The battle over the firing of Theater J artistic director Ari Roth took another bitter turn this week, with the circulation of remarks by his boss at the D.C. Jewish Community Center, Carole R. Zawatsky, accusing him of “a pattern of insubordination, unprofessionalism and actions that no employer would ever sanction.”

That pattern, Zawatsky charged in a letter sent by e-mail Wednesday to “Members of the Israel arts community,” included an attempt “to force the DCJCC to give up Theater J to his sole control.” She added that after that failed to occur, “he had begun to work on a new venture, while still employed by DCJCC,” and that “despite clear and written warnings” he “continued to disregard direction” from his superiors.

“Ari Roth,” she contended, “was not fired because of his politics or because of outside pressure.”

From “The Facts on the Ground at Theater J” by Isaac Butler in American Theatre magazine, December 28, 2014:

In their own ways, both Zawatsky and Roth’s versions of the story identify the same problems: an untenable relationship between the theatre and the center, mirrored or manifested by their own untenable relationship; a document outlining possible ways those relationships could change; and Roth’s future plans for a new company and decision to leave. But both use these points of evidence for radically different, somewhat incompatible interpretations of the last few years.

And if you assume the politics of Israel-related programming was the cause of Roth’s firing, a few additional ironies seep into the story. For one, Roth is hardly a radical leftist on Israeli politics: He is instead a mainstream, left-of-center, two-state-solution-supporting moderate. He has said, both in his interview with HowlRound and with me, that he willingly embraced the DCJCC’s “red line” about work that promotes BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions, a movement that tries to use economic and cultural pressure to end Israeli occupation of Palestinian land).

What’s more, the work that actually landed him in hot water in the first place was a staged examination of whether or not a play by the greatest living English-language playwright was anti-Semitic—and then two plays by Israeli Jews attempting to reconcile with the events surrounding their nation’s founding.

But the past is prologue. Leaving aside the trail of events that brought Roth, Zawatsky, Theater J and the DCJCC to this impasse, the question is: What now?

* * *

I will continue to add to and amend this post if I discover thoughtful and pertinent information I believe to be constructive to the narrative and the issues.

April 10th, 2014 § § permalink

It is unquestionably a sign of his achievements at The Young Vic that David Lan has been named consulting artistic director for the planned arts centre at the site of the former World Trade Center in lower Manhattan.

Selection to be a part of this important element in rebuilding Ground Zero, the site of the 2001 terrorist attacks, was also a mark of achievement for, among others, Signature Theatre Company, architect Frank Gehry, and The Joyce Theatre.

But in the ensuing 10 years, the Signature abandoned its for Ground Zero and successfully built and opened a three-theatre complex on West 42nd Street. Gehry’s involvement going forward is in limbo. The Joyce, a home to numerous dance companies, still hopes for a role in programming the arts center, but has seen plans for the largest theatre among the three still under discussion drop from 1,000 seats to 550, only slightly larger than their longtime home. In the scheme of New York theatres, the city’s relative paucity of 1,000 seat venues other than on Broadway might have been more useful to the ecology of the arts.

Mayor Bloomberg, whose administration was involved in discussions for the redevelopment plans over his 12 year tenure, is out of office now. Before leaving, he allocated $50 million in city funds to a rival new arts facility, the Culture Shed, but none for the Ground Zero project. The city’s new mayor, Bill de Blasio, has yet to appoint a cultural affairs commissioner and is quiet on the project.

Even Mr. Lan’s participation seems somewhat fleeting, in that his appointment is only through September and he has told The New York Times that he does not foresee a programming role for himself. Maggie Boepple, president of the arts center’s seven member board (Stephen Daldry was recently named to the group) told the Times that there was no need for full-time artistic leadership because performances won’t begin until 2018 or 2019. What creative influence will Lan’s temporary engagement have in the next six months?

When the arts centre concept was first announced, the talk was heartening. The city committed to the idea that the arts had both a spiritual and economic role to play in healing lower Manhattan. Over time, the importance of that message has eroded.

Given the planning, emotional and political implications that surround the rebuilding of Ground Zero, it’s difficult not to be sceptical. The Wall Street Journal cites a daunting cost of $469 million, with only $155 million allocated by the federal government. Fundamentally, the Ground Zero Arts Center is a real estate project first and an arts project second, and that often places impractical burdens on creative work. Even during his limited engagement, I hope Mr. Lan can talk frankly and practically, challenging all existing presumptions, if the project is to ever succeed.

January 26th, 2014 § § permalink

This post has been updated, and a story that began as an account of censorship has become one of, dare I say it, resurrection. Here’s the tale.

This post has been updated, and a story that began as an account of censorship has become one of, dare I say it, resurrection. Here’s the tale.

Three days ago, the town council of Newtownabbey in Northern Ireland shut down a planned engagement of the Reduced Shakespeare Company’s The Bible: The Complete Word of God (abridged) on the grounds that it was sacrilegious and anti-Christian. In doing so, they overrode the prior decision by the town’s Artistic Council to allow the show to go forward in a town-financed facility. I abhor this action in no uncertain terms, and anything I write would simply be variations on that theme. So rather than embroider my own thoughts, I offer you – consistent with the practices of my friends at Reduced – a relatively brief compendium of what has occurred since the first announcement, all via local coverage from Ireland (links to each complete story are contained in the name of each press outlet), as well as select comments from Reduced’s chief twit Austin Tichenor. I trust you’ll see this for what it is, censorship, pure and simple.

From the Newtownabbey Times, “Artistic board axes controversial theatre show”:

Newtownabbey Council’s Artistic Board has cancelled a comedy show due to take place at Theatre at The Mill next week, following complaints that the production would be offensive to the borough’s Christian community.

The move to pull ‘The Bible: The Complete Word of God (abridged)’ comes after councillors and officers received correspondence from individuals and church leaders calling for the “blasphemous” show to be axed.

At Monday night’s Development Committee meeting, several councillors voiced their objection to the Reduced Shakespeare Company production taking place at the council-run venue. And there was significant support for a proposal from DUP councillor Audrey Ball calling for it to be cancelled.

Other members argued against “political censorship” of productions and a decision on the issue was deferred to allow council officers time to look at potential contractual and financial implications arising from stopping the show just days before the scheduled start of its two-night run.

From UTV, “Bible theatre show cancelled after row”:

The party’s Robert Hill told UTV on Thursday that members of the public had approached representatives asking them to “get it stopped” on the grounds that it was offensive.

He said the council was “willing to take a moral stand” and hit back at those who have criticised the decision by claiming it amounts to censorship of the arts.

“Every film in the theatre is censored – that’s why there are age limits on what can be seen and what can’t. And where do you stop? There has to be a limit somewhere,” Mr Hill said.

UUP Mayor Fraser Agnew also told UTV that he felt the right decision had been made regarding the controversial play, adding that a professional facilitator had been brought in to resolve the issue.

“There were a lot of people concerned about the nature of this play, that it was anti-Christian – and we have established indeed it was anti-Christian,” he said.

From the Belfast Telegraph, “Bible spoof play ban makes Northern Ireland a laughing stock”:

The decision by Newtownabbey Borough Council to cancel the Reduced Shakespeare Company’s light-hearted revue of the Bible gives religion a bad name.

The decision by Newtownabbey Borough Council to cancel the Reduced Shakespeare Company’s light-hearted revue of the Bible gives religion a bad name.

It also underlines the backwoods narrow-mindedness of some people in Northern Ireland as it begins to show a more multi-cultural face to the world.

We must ask ourselves where else would this happen, except among the Taliban in Afghanistan?

Surely God must have a sense of humour – how else could he put up with the numpties of Newtownabbey?

From BBC News, “Comedian Jake O’Kane criticizes ‘zealots’ who cancelled play”:

Mr O’Kane said: “I haven’t seen the play, and unfortunately I’ll never be able to see the play because councillors have decided that we will not be allowed to see the play.

“It’s like getting in a time machine and they went back to before the Reformation and the Enlightenment.

“There was £7m spent on this theatre, it opened in 2010, and they may as well close the doors. If they are going to be the moral guardians of what we see and don’t see, that theatre is dead in the water.

“We already have laws, we have hate speech laws, that dictate what the arts can and cannot do. If it is hateful, if it is against minorities, the laws are already there to censor that.

“We don’t need a bunch of unionist councillors in Newtownabbey deciding what we can or cannot go to see.

“They call themselves moral guardians – they weren’t elected to be moral guardians. We elected them to empty our bins, make sure the leisure centres were open – that’s the powers they have.

From the Newtownabbey Times, “Council faces stinging criticism over decision to axe show”:

One Belfast newspaper claimed that the board’s decision had made Northern Ireland “a laughing stock”, while playwright Dan Gordon said it was “staggering that this type of censorship still appears to flourish in the UK.”

Alliance Alderman John Blair said that cancelling the show had “brought us back into the Dark Ages and turned us into a laughing stock”. But Alderman Billy Ball argued that the board had made “the right decision,” while Raymond Stewart, secretary of Reformation Ireland, welcomed the move to axe what he branded “an insult upon our Lord Jesus Christ and His gospel.”

From BBC News, “Banned play: Arts minister ‘saddened’ by council decision”:

In a statement, the arts minister said: “I was disappointed to hear of the decision to cancel the production of The Bible: The complete Word of God (Abridged).

In a statement, the arts minister said: “I was disappointed to hear of the decision to cancel the production of The Bible: The complete Word of God (Abridged).

“I know that the play has travelled extensively and been performed on the international stage for the past 20 years.

Arts Minister Carál Ni Chuilín said audiences should be given the opportunity to “judge for themselves”

“I am saddened that audiences here will not be offered the opportunity to see the performance and judge for themselves the virtues of the show,” Ms Ni Chuilín added.

“I fully support the views of the Arts Council that the artist’s right to freedom of expression should always be defended and that the arts have a role in promoting discussion and allowing space for disagreement and debate.”

From the Irish Indpendent, “Cancellation of ‘blasphemous’ play interferes with freedom of speech: Amnesty International”:

Amnesty Northern Ireland director Patrick Corrigan said: “It is well-established in international human rights law that the right to freedom of expression, though not absolute, is a fundamental right which may only be restricted in certain limited circumstances to do with the advocacy of hatred.

“It is quite obvious that those circumstances are not met in the context of this work of comedy and, thus, that the cancelling of the play is utterly unjustified on human rights grounds.

From The Belfast Telegraph, “Bible play goes on in Newtownabbey… but only behind closed doors”:

The company behind the show, Newbury Productions and Reduced, have told this paper that they have already booked flights and accommodation and intend to come to Newtownabbey as planned.

They will take to the stage at the Theatre At The Mill for technical and dress rehearsals ahead of the rest of a UK tour, which takes in more than 40 venues in England, Scotland and Wales.

Last night a spokeswoman for Newtownabbey Borough Council confirmed the public would not be permitted access to watch the rehearsals.

“As is normal practice, dress rehearsals are not open to the public,” she added.

It has cost the council at least £2,000 to cancel the show.

Davey Naylor, general manager of Newbury Productions, told the Belfast Telegraph that tech and dress rehearsals will be taking place at Theatre At The Mill on January 29 and 30 as planned.

He said: “We will be there, we just won’t be able to perform for the public at the theatre.”

From The Irish News, “Comedy company considers other venues for Bible show”:

Last night the show’s producers – who revealed it was the first time in 20 years the production had been cancelled – said they would definitely consider returning at another date.

Davey Naylor said they believed the “good people of Northern Ireland should be free to come and see the show to make up their own minds”.

He added: “Sadly, at this late stage, I think another performance next week is remote, however, our tour goes on until April and there’s no reason we couldn’t come back at some point.”

By sheer coincidence, the website Upworthy happened to feature a video by Monty Python member John Cleese, “On Creativity: Serious vs Solemn,” which seems particularly apt to this situation, billed by Upworthy as, “John Cleese Describes Why Nothing Is ‘Too Serious’ To Be Joked About”:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gdWKQ36JkwE

I sincerely hope that the Reduced Shakespeare Company does return to play Newtownabbey. I suspect they need a good laugh there just about now.

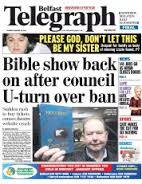

Update, January 27 8:15 pm

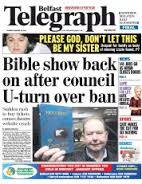

From The Belfast Telegraph, “Newtownabbey Borough Council has reversed the controversial decision to ban comedy play The Bible: The Complete Word Of God (Abridged).”

From The Belfast Telegraph, “Newtownabbey Borough Council has reversed the controversial decision to ban comedy play The Bible: The Complete Word Of God (Abridged).”

The Reduced Shakespeare Company production is expected to run as originally scheduled on Wednesday and Thursday this week. Anger had been growing since it was revealed the council’s artistic board – made up of councillors and independent members – had pulled the plug on the show at Newtownabbey’s Theatre At The Mill

DUP members had branded the pay blasphemous and an attack on Christianity, but the decision caused outrage and made international headlines. But on Monday night the artistic board announced it had reversed its decision – an announcement that was backed by the full council.

From the BBC, “Newtownabbey council reverses decision to cancel Bible play”

Austin Tichenor of the Reduced Shakespeare Company said: “I’m thrilled that the Newtownabbey community can now come see the show and decide for themselves what kind of a show it is. “My biggest fear is that they’ll come see the show and go ‘this is what all the fuss was about?’. I think people assume we’re coming from a place of hatred and mockery and we’re absolutely not. This is a celebration of the Bible and I think anybody who has seen the show, and many people of all faiths have seen the show, testify to that effect.”

And, I trust a good time will be had by all.

And, I trust a good time will be had by all.

Update, January 30, 11 am:

October 30th, 2013 § § permalink

Position 1: a stage production that is recorded, filmed or actually broadcast live ceases to be theatre. It may be considered television or film, but it is a record of theatre, not the thing itself. True theatre is experienced in the flesh, so to speak.

Position 2: for people who have no means to see any theatre, or a specific production, a recording or live transmission of the event, whether it occurs in a movie theatre or on a computer, is better than not seeing it at all, provided it is at least competently produced.

Position 3: even though it means I don’t get to see some things that really interest me, I don’t enjoy recorded theatre, no matter how artfully done, and I’m lucky enough to have access to lots of great theatre live, so after a few tries, I now don’t go. But that shouldn’t stop anyone else.

Why have I laid out these positions so baldly, rather than making a case for them? Because I want to talk about an aspect of the growing appetite for cinecasts, NT Live, the home delivery Digital Theatre and the like that isn’t about the viewing experience at all. That’s a matter of opportunity and preference and I leave it to everyone else to hash out those issues. My interest in this trend is about how it is branding certain cultural events and producers – and how U.S. theatre is quickly losing ground.

Why have I laid out these positions so baldly, rather than making a case for them? Because I want to talk about an aspect of the growing appetite for cinecasts, NT Live, the home delivery Digital Theatre and the like that isn’t about the viewing experience at all. That’s a matter of opportunity and preference and I leave it to everyone else to hash out those issues. My interest in this trend is about how it is branding certain cultural events and producers – and how U.S. theatre is quickly losing ground.

In general, people attend commercial theatre based upon the appeal of a production – cast, creative team, author, reviews, word of mouth, etc. Who produced a show is pretty much irrelevant, and only theatre insiders can usually tell you who produced any given work. In institutional theatre, the producer has more impact, as people may attend because they have enjoyed a company’s work previously, because it conveys a certain level of quality. This is true in major cities and regionally, and while the name of the theatre alone isn’t sufficient for sales, it is a factor in a way it isn’t in the West End or on Broadway.

As a result, what is happening with theatrecasts is that the reach of the companies utilizing this opportunity is vastly extended, and the brands of the companies travel far beyond those who sit in their seats or regularly read or hear about their work. There’s long been prestige attached to The Royal Shakespeare Company, the Metropolitan Opera and the National Theatre; now their presence in movie theatres has served to increase access and awareness. These longstanding brands are being burnished anew now that more people can actually see their work. The relatively young Shakespeare’s Globe, even as it makes its Broadway debut, is also gaining recognition thanks to recordings of their shows.

As a result, what is happening with theatrecasts is that the reach of the companies utilizing this opportunity is vastly extended, and the brands of the companies travel far beyond those who sit in their seats or regularly read or hear about their work. There’s long been prestige attached to The Royal Shakespeare Company, the Metropolitan Opera and the National Theatre; now their presence in movie theatres has served to increase access and awareness. These longstanding brands are being burnished anew now that more people can actually see their work. The relatively young Shakespeare’s Globe, even as it makes its Broadway debut, is also gaining recognition thanks to recordings of their shows.

It should be noted that for UK companies, “live” is a misnomer when it comes to North American showings. We’re always seeing the work after the fact, given the time difference, so in many ways it’s no different than a pre-recorded stage work on PBS. But the connotation of live is a valuable imprimatur, and few seem to mind it, even when there are “encore” presentations of shows from prior years. The scale of a movie screen, the quality of a cinema sound system appear to be the true lure, along with the fact that these are not extended engagements, but carefully limited opportunities that don’t compete with actual movie releases.

MEMPHIS, one of the rare U.S. originated cinecasts

Regretfully, by and large, American theatre (and theatres) are missing the boat on this great opportunity for exposure, for revenue, for branding. There have been the occasional cinecasts (Memphis The Musical; Roundabout’s Importance of Being Earnest, imported from Canada’s Stratford Festival) but they’re few and far between. We’re about to get a live national television broadcast of the stage version of The Sound of Music, but it’s an original production for television, not a stage work being shared beyond its geographic limitations. Long gone are the days when Joseph Papp productions of Much Ado About Nothing and Sticks And Bones were seen in primetime on CBS; when Bernard Pomerance’s The Elephant Man was produced for ABC with much of the original Broadway cast; when Nicholas Nickleby ran in its entirety on broadcast TV; when PBS produced Theatre in America, showcasing regional productions, when Richard Burton’s Hamlet was filmed on Broadway for movie theatre showings 50 years ago.

London MERRILY rolled across the Atlantic

Most often, when this topic comes up in conversations I’ve been party to, there’s grumbling about prohibitive union costs as a roadblock. Perhaps the costs have changed since the days of many of the examples I just cited, yet somehow Memphis and Earnest surmounted them. Even as someone who doesn’t particularly care to see these recorded stage works, I worry that American theatre is lagging our British counterparts in showcasing work nationally and internationally, in taking advantage of technology to advance the awareness of our many achievements. Seeing an NT Live screening has become an event unto itself – this week the National’s Frankenstein is back just in time for Halloween; the enthusiasm last week for the cinecast of Merrily We Roll Along (from the West End by way of the Menier Chocolate Factory) was significant, at least according to my Twitter and Facebook feeds. The appetite is also attested to by an online poll from The Telegraph in London, with 90% of respondents favoring theatre at the movies (concurrent with an article about the successful British efforts in this area). I’d like to see this same enthusiasm used not just to bring U.S. theatre overseas, but to bring Los Angeles theatre to Chicago, Philadelphia theatre to San Francisco, Seattle theatre to New York, and so on – and not just when a show is deemed commercially viable for a Broadway transfer or national tour.

I’m not trying to position this as a competition, because I think there’s room for theatre to travel in all directions, both at home and abroad. But without viable and consistent American participation in the burgeoning world of theatre on screen, we run the risk of failing to build both individual brands and our national theatre brand, of having our work diminished as other theatre proliferates in our backyards, while ours remains contained within the same four walls that have always been its boundaries and its limitations. Somebody needs to start removing the obstacles, or we’re going to be left behind.

March 5th, 2013 § § permalink

As I said in Part 1 of this series, Matt Trueman’s piece for the Financial Times got me thinking about a variety of issues relating to the exchange of new plays between England and the United States. After focusing on perceived favoritism or bias, and then the common issue of support beyond the box office and its apparent impact on new work, let me circle back to focus more directly on the original issue.

I agree with Trueman, and the people with whom he spoke, that despite a handful of big name plays traversing the pond every year, each country only scratches the surface of the vast number of plays produced by the other. Now, unencumbered as I am by more comprehensive data, what could be the causes for this?

Personally, I don’t really hold with the idea that some of the plays are mired in cultural differences not readily understood. I have certainly seen plays in which cricket plays a role (I don’t understand anything connected with cricket), but the plays aren’t about cricket, and the minutiae of the game is typically irrelevant. We may mention footlong sandwiches in a play, calling them subs, grinders or hoagies, but so long as it’s clear its an item of food, either from other dialogue or stage action, I don’t think English theatergoers would be lost in incomprehension. We may not know the particulars of the National Health Service, or the English may not understand the nuances of city, county, state and national government here, but those are mechanics, not meaning. If we can find common ground in Monty Python and Downton Abbey, I have no worries about plays – even those that require specific regional accents.

I certainly think familiarity and awareness plays a role, and it amplifies a frequent intra-country challenge: if a play is produced in a regional theatre outside of a major media area, how does it get noticed? I don’t doubt that large theatres in both countries have the means and the inclination to look beyond New York and London alone, but how do they look? Literary offices are likely stocked with unread homegrown material, even if they only accept work by agent submission. Media websites may offer reviews of work, but who has the time to scan it all on a daily basis, hunting for a lesser known but worthwhile work. If a play doesn’t get published, or added to the catalogue of a major licensing house, how does it get attention, at home or abroad? Some may like to decry the influence of reviews, but good reviews distributed by theatre or producer may have the most impact, but is there a readily accessible list of artistic directors and literary managers in both countries (and other English-speaking countries) to make the dissemination of that material efficient? To be interested in a play, one first has to hear or read about it.

But let me come back to “homegrown.” In America, we constantly see mission statements that, rightly, talk about theatres serving their community. This can take many forms and be interpreted in a variety of ways, but the fact is that even those not-for-profit companies which also speak of adding to the national and even international theatrical repertoire must first and foremost serve their immediate community, the audience located in a 30 mile radius of their venue, give or take. Many theatres are also making an increased effort to serve the artists in their local community as well, instead of importing talent from one of the coasts. I have no reason to suspect that it is any different in England.

So the question about producing plays from other countries is less one of interest than adherence to mission. If your theatre is the only one of any scale for 30 miles, or the largest even in a crowded field, where should your focus be? Unless your company is specifically dedicated to work from other countries, on balance it’s going to be wise to focus on homegrown plays, especially if your company does new work.

Several months back, the artistic director of a large U.S. theatre and I were discussing a British playwright we both hold in high regard, but the A.D. said he couldn’t make room for that author’s work in a season, even for a U.S. premiere. “If I do that, that’s one less slot I have for a new American play.” With most theatres having perhaps four to seven shows a season, not all necessarily new, it is in fact a tricky political prospect to debut or produce foreign work. Look at the flack Joe Dowling took for his season of Christopher Hampton plays at The Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis.

Add to that the necessity of balancing a season for gender and race, plus the desire to show the audience work that may have debuted elsewhere in the U.S., as well as classics and the challenge grows greater for foreign work (though it doesn’t justify our significant blind spot towards our neighbor Canada or the limited awareness of theater from Australia and New Zealand either). I suspect this comes into play in England as well, but I’d need to speak with more English A.D.’s to know.

When I surveyed the Tony nominations it was quickly apparent that if one removed David Hare, Tom Stoppard, Martin McDonagh, Brian Friel and Yasmina Reza, foreign presence on Broadway would drop precipitously; the same would happen at the Oliviers if one excluded Tony Kushner, August Wilson, and David Mamet. Yes, England has premiered work by Katori Hall, Bruce Norris and Tarrell Alvin McCraney, but they are exceptions to the rule, not exemplars of a new trend.

I support the exchange of dramatic literature and artists between countries – all countries –not just the U.S.-English traffic that has been the focus here. Improved communication about that work might help to foster an increase and, as I said originally, a survey of past productions on a larger scale might reveal more than we’re aware of. But when it comes right down to it, English theatres and artistic directors must focus on what’s most important for their audiences, and American theatres and A.D.s must do the same. What that yields in terms of exchange is simply part of balancing so many necessary elements, tastes, styles and budgets; trends may appear when looking from a distance, but up close, it’s a theatre by theatre function.

March 5th, 2013 § § permalink

In the process of debunking the idea that English and American plays experience bias, for or against them , when produced in the their “opposite” theatrical cities of New York and London, I began to notice something extremely interesting about the origin of plays nominated for the Olivier and Tony Awards. Thinking it might be my own bias coming into play as I assembled data, I expanded my charts of nominated plays beyond simply the country of origin for the works, adding the theatres where the plays originated. What I found suggests that the manner of theatrical production in the two countries may be even more alike than many of us realize.

In the U.S., of the 132 plays nominated for the Tony Award for Best Play between 1980 and 2012, 61 of them had begun in not-for-profit theatres in New York and around the country. That’s 46% of the plays (and even more specifically, their productions) having been initiated by non-commercial venues. In England, 99 of the plays came from subsidised companies, a total of 75% of all of the Oliviers nominees.

Together, these numbers make a striking argument for how essential not-for-profit/subsidized companies are to the theatrical ecology of today. And, frankly, my numbers are probably low.

To work out these figures, I identified plays and productions which originated at not-for-profits. That is to say, if a play was originally produced in a not-for-profit setting, but the production that played Broadway was wholly or significantly new, it was not included. As a result, for example, both parts of Angels in America don’t appear in my calculations, because the Broadway production wasn’t a direct transfer from a not-for-profit, even though its development and original productions had been in subsidized companies in both the U.S. and England.

These statistics also don’t include plays that may have been originally produced in their country of origin at an institutional company, but were subsequently seen across the Atlantic under commercial aegis. So while Douglas Carter Beane’s The Little Dog Laughed is credited with NFP roots in the U.S. it has been treated as commercial in London. Regretfully, I don’t know enough about the origin of all nominated West End productions in companies from outside London to have represented them more fully, which is why I have an inkling that the 75% number is low.

Additionally, it’s worth noting that in England, the Oliviers encompass a number of theatres that are wholly within subsidized companies, in some cases relatively small ones, which needn’t transfer to a conventional West End berth to be eligible; examples include the Royal Court and the Donmar Warehouse, as well as Royal Shakespeare Company productions that visit London. While there are currently five stages under not for profit management on Broadway (the Sondheim, American Airlines, Beaumont, Friedman Theatres and Studio 54), imagine if work at such comparable spaces as the Mitzi Newhouse, the Laura Pels, The Public, The Atlantic and Signature were eligible as well.

Why am I so quickly demonstrating the flaws in my method? Simply to show that even by conservative measure, it is the institutional companies, which rely on grants, donations and government support to function, which are producing the majority of the plays deemed to be the most important of those that play the major venues in each city.

Since we must constantly make the case for the value of institutional, not-for-profit, subsidized theatre, in the U.S. and in England (let alone Scotland, Ireland, Canada and so many other countries), I say tear apart my process and build your own, locally, regional and certainly nationally. I think you’ll find your numbers to be even stronger than mine and, hopefully, even more persuasive. While it may seem counterintuitive for companies outside London and New York to use those cities’ awards processes to make their case, the influence is undeniable.

March 5th, 2013 § § permalink

The conventional wisdom in theatrical circles is that America is stunningly Anglophilic, that we readily embrace works from England on our stages. Supposedly we do this to the detriment of American writers, and our affection is reputedly one-sided, as the British pay much less attention to our work. So they say.

This past weekend, British arts journalist Matt Trueman began a worthwhile conversation in an article for the Financial Times, in which he suggested that most American plays rarely reach England, and vice-versa. While a few of the assertions in the piece may not be wholly accurate, I think the central argument holds true: only a handful of plays from each country get significant exposure in the other. His piece set me thinking.

Much of America’s vision of British theatre is dominated by the fare on Broadway and, I suspect, it’s the same case in the West End for America. Now we can argue that these two theatrical centers don’t accurately represent the totality or even the majority of theatre in each country (and I have done so), but the high exposure in these arenas does have a significant impact on the profile and life-span of new plays, fairly or not. Consequently, our view of the dramatic repertoire from each country to the other is a result of a relative handful of productions in very specific circumstances.

Given the resources and data, one could perhaps build a database of play production in both countries and extract the most accurate picture. But in an effort to work with a manageable data set in exploring this issue, I took the admittedly subjective universe of the Best New Play nominations for the Tony and Olivier Awards, from 1980 to today. While significantly more work is produced than is nominated, this universe at least afforded me the opportunity to examine whether there is cultural bias among select theatrical arbiters. Although each has its own rules and methodology (I explain key variables in my addendum below), they are a microcosm of top-flight production in these “theatre capitals.”

So as not to keep you in suspense, here’s the gist: new English and American plays are nominated for Tony and Oliviers at roughly the same rate in the opposite country, running between 20 and 25% of the nominees when produced overseas.

In the past 33 years of Tony Awards, 32 English plays were nominated for Tonys out of a universe of 132, or 24% of the total. At the Oliviers, 20% of the Best New Play nominees were American. In my eyes, that 4% difference is irrelevant; though there’s no margin for error since this isn’t a poll, the total numbers worked with are small enough so that a few points means only a few plays, in this case, only five.

Now, let’s take a step back and look at this with larger world view. While Americans at large may have a tendency to blur distinctions between English, Welsh, Irish and Scottish, I’m aware that these national distinctions are extremely important. Blending these countries in our view of theatrical production may be contributing to the false American perception of English imperialism on our stages.

Factoring in all productions by foreign authors (the aforementioned Ireland, Wales and Scotland, as well as France, Canada, Israel and South Africa), we find that 44 plays from outside the U.S. received Tony nominations in 33 years, for 33% of the total nominees, while in England, foreign plays garnered 52 Olivier nods, for 39% of the total. So while the gap here is slightly wider, it shows that English plays actually are nominated less in their own country than American plays are at the Oliviers.

When it comes to the recognition of plays that travel between these two major theatrical ports of call, I think it’s fair to say that, so far as each city’s major theatrical award is concerned, there is no bias, no favoritism. Even if the number of plays being produced are out of balance, the recognition is proportional. Perhaps we can put that old saw to rest.

P.S. For those of you feeling petty, wondering whether there’s an imbalance in winners? American plays have won the Olivier nine times since 1980, while English authors have won the Best Play Tony seven times. So there.

* * * * *

Notes on methodology:

- Musicals were not studied, only plays.

- There is one key difference between the Best Play categories at the Tonys and The Oliviers, specifically that the Oliviers also have a category for Best Comedy in many of the years studied. While it is not included in this comparison, it should be noted that, with a few exceptions, American plays were rarely nominated in the Best Comedy category. Whether this is a result of U.S. comedies not traveling to England at all, or cultural differences causing U.S. comedies to be poorly received when they did travel, was not examined.