Let’s be honest. If you didn’t follow documentary filmmaking or live and die by theatre news, Hands on a Hardbody would sound like something that might play late at night on Cinemax. Those of a certain age might think it was a belated sequel to the 1984 teen sexploitation comedy Hardbodies (think Porky’s, with less class). But the fact is, that title was very likely a deterrent to audiences, even with “a new musical” appended to it, which is seemingly de rigeur these days, despite having been brilliantly parodied years ago by The Musical of Musicals (The Musical!).

It’s not my habit to write critiques of shows, and I’m not about to break that practice, but with Hands on a Hardbody now closed, I feel a bit freer to engage in analysis of the show’s marketing. In my outsider assessment, it didn’t manage to sufficiently surmount the challenges inherent in the show, attested to by the consistently low grosses throughout previews and the four weeks of the regular run. Hardbody built up no head of steam, no significant name recognition and apparently no advance sales, despite the usual potpourri of discounts. Frankly, if it came up in any of my discussions, I couldn’t make it sound inherently appealing either.

If, as some suggest, the theatergoing audience is finite, and fragmented by the welter of openings each spring, then Hardbody was starting at a disadvantage. Though it was based on a well-received documentary, it didn’t come with name recognition, since the film is 17 years old and grossed less than a half-million dollars; though its creative credentials were impressive, how many new musicals are sold solely on the strength of their writing team nowadays; it had a talented cast with several names well-known to theatre audiences (particularly Keith Carradine and Hunter Foster), but there was no Tom Hanks, Bette Midler or Alec Baldwin to tap into the celebrity buzz machine.

Mind you, I don’t mention the foregoing to say that they are absolute necessities for Broadway success. How many people really knew Once the movie before the show opened (with the benefit of starting at New York Theatre Workshop)? Were Jonathan Groff and Lea Michele big names before Spring Awakening? Who on earth was Lin-Manuel Miranda or Quiara Alegria Hudes in the public imagination before In The Heights?

This could be looked at as Monday morning quarterbacking, but the title must have suggested a challenge to the creative and producing teams up front. There was a change made from the documentary name, merging what had been “Hard Body” into “Hardbody.” Perhaps this means something to those who are truck aficionados, but in the steep canyons of New York (and let’s remember that new Broadway shows don’t often reach the tourist market right away), I fear this ultrafine distinction was lost.

Going back to my earlier comparison to late-night cable, I’m not sure whether “hard body” or “hardbody” is an important distinction; I also wonder about some of the glistening bodybuilders who beckon from magazine covers on the newsstand when those words are deployed. In any event, the title didn’t bring any marketing recognition to the table; perhaps it deserved something that would have moved us into the realm of the mythic, rather than grounding us, enigmatically, in the truck at the center of the show. Sometimes, being too loyal to source material can be counterproductive.

TV ads I saw seemed to be on the right track, emphasizing the spirit of competition. To be sure, playing up to TV’s countless reality contests wasn’t a bad strategy. I just wonder whether they went far enough, or – once again – were clear enough. You could (pardon the expression) drive a truck through the space between winning a motor vehicle and a better life. The campaign needed to express something between a pickup with a foreign brand name and a nebulous American dream. Unfortunately, few shows could have mounted the series of ads that might have prompted audiences to feel they had a stake too.

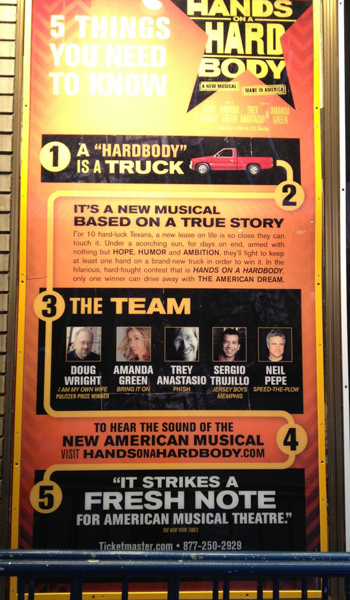

Where I really worried for the show was in its big three-sheet in Shubert Alley, long considered prime display space for Broadway shows, much sought after and fought over. I’ve reproduced it here so you can see exactly how eye-catching it wasn’t. Frankly, it could be compared to everything from a flow chart to a child’s board game to assembly instructions, and it required a close read for it to register at all. In trying to do everything, it did almost nothing, and even marred by amateur photography here, it sure remains one of the most confusing images I’ve ever seen put to use in advertising a Broadway show, or any form of entertainment, for that matter. If this was also used in print ads I can’t say, having shifted to almost exclusively digital readership; it might have worked if you were holding it in your hands, but it still would have been quite the jumble compared to the simplicity of The Phantom’s mask or the Jersey Boys in lights.

You can debate the pros and cons of the show among yourselves, but the failure for Hardbody to gain even initial traction is evidence of a communications strategy that couldn’t pump up any meaningful interest, leaving the show in the hands of the critics and an uninformed base of ticket buyers at the most Darwinian time of the year. Ironically, in preparing this piece, I found the cover of a home video release of the documentary and it had a rather intriguing tagline that might have been provocative and helpful to the show: “You lose the contest when you lose your mind.” Turned around so that it didn’t harp on losing (negatives are, funny enough, not positive in advertising), there was still something there: a sense of mental toughness, of endurance, even of the potential for madness. And if reality TV has taught us nothing, those are qualities people like to watch.

So I mourn the closing of the possibly misunderstood Hands On A Hardbody both because it was a show that dared to not fit some standard Broadway formula and because its closing probably scared producers and investors for future projects that don’t fit the mold. I hope that’s not the case.

But I’ve found a great new opening night gift for the brave souls who dare to take on Broadway with new material in particular: “You lose the contest when you lose your mind.”

I do like some of the visual elements, especially in how the tv ad uses them, but even there, it’s confusing. Looking at the logo alone–and it’s clearly a logo, designed for hats, shirts, etc–it’s still not clear that it’s a show about a truck. Maybe if the shape were more evocative of an auto company’s badge, perhaps against a background that reminded us of the front grille of a truck, it would make more subliminal connections. The text inside is just fine, but the star shape makes no sense, makes me think instead of star-making reality shows like American Idol et al.

When it was originally announced as going to Broadway, I asked around out here to see what people thought. Bear in mind, I live in pickup country. But to a one, people I talked to thought it was about people & sex based on the title. After explaining the story, the most common reaction was, “Why would I want to see a musical about a truck?” Whatever the merits of the show, I suspect it would have been hard to get past that question.

But of course, it was not about the truck, it was about the people who hoped to win the truck. That’s why I liked the TV spot: the focus on the people, not the vehicle. But anyone wanting to understand the challenge of “hardbody” should search for that term on Google Images or Bing. Yow.