I don’t know that I saw Kilty during the last 20 years of his life. Perhaps we ran into one another in a few theatre lobbies, I would occasionally hear a little something about his health, but he was long out of my mind and, I fear, the minds of many others who knew him during his lengthy theatrical career. So when I first saw a news story from a small Connecticut publication reporting that he had died, at age 90, in a car crash, I surprised myself with the depth of my feeling.

I don’t know that I saw Kilty during the last 20 years of his life. Perhaps we ran into one another in a few theatre lobbies, I would occasionally hear a little something about his health, but he was long out of my mind and, I fear, the minds of many others who knew him during his lengthy theatrical career. So when I first saw a news story from a small Connecticut publication reporting that he had died, at age 90, in a car crash, I surprised myself with the depth of my feeling.

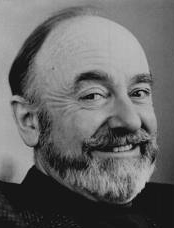

I had met Jerome Kilty immediately upon my college graduation, when I went to work as a press assistant at the Westport Country Playhouse. Kilty (as many called him when speaking of, not to, him) was part of the Westport theatre crowd, a fairly tight-knit group of theatre pros who had moved to the Connecticut countryside in the 50s and 60s, long before its main street became lined and littered with chain stores, before big box stores cropped up along once bucolic Route 1. He only performed at Westport once during my two summers there – a benefit reading of his own Dear Liar, playing the role of George Bernard Shaw – but he seemed to be around so often, an impression helped, no doubt, by the schedule of 11 shows in 11 weeks, meaning opening nights every Monday between June and August, the central event of Westport’s theatrical social circle. Then, magically, when I went to Hartford Stage, there was Kilty again, acting in the first show of the season and acting and directing in the third, the former a Shakespeare play, the latter a Shaw.

Kilty was a character from another era – actor, director, playwright; a man who had worked with the stage greats of the 50s, who had founded theatres and, with Dear Liar, written theatre’s most successful epistolary two-hander (until Pete Gurney overtook him with Love Letters). I remember sitting in my little office as he told me the story of his army leave in England, when he trekked to George Bernard Shaw’s home and, denied an audience with the great man, how he scooped some pebbles from Shaw’s driveway as keepsakes and how they still sat on his mantel as we spoke. The people we meet at this age make such an outsized impression when they deign to give us their attention, their time, their interest. Kilty embodied the perfect English gentleman – which is ironic since, as I would learn, he had been born on a California Indian reservation.

When I read of Kilty’s death, I knew that he left no survivors and I feared that his passing would go largely unnoticed, which struck me as profoundly sad, for a man of accomplishment. Having been raised in the climate of old media, I felt that he was deserving of a New York Times obituary, an honor he would have appreciated. So I forwarded to news story to the theatre editor, commenting that this was a man worthy of a final recognition. I made a few calls, I wracked my own memories, and provided what little material I could when called by the reporter working on the piece, all the while feeling inadequate to the task, regretful that I had not seen this lovely man in so very long, and determined that he have this one last moment in the spotlight.

The Times did well by Kilty, and I think that the reporter, Dennis Hevesi, was as charmed by Jerry, even in death, as I was in my youth several decades ago. I was so pleased to see this final remembrance, and both pleased and surprised when, on a Sunday morning in southern New Jersey, I saw it as well in the pages of The Philadelphia Inquirer, via the Times news wire. Perhaps it appeared in many other papers and websites (previously, Robert Simonson had written an even more thorough article for Playbill); perhaps it reached others long out of touch but who took a moment to commemorate Kilty privately when they learned of his passing.

I write this not out of pride in my role in this obituary, or to demonstrate that I can contact the right people at the Times. I know that the decision to write about Kilty was ultimately theirs, based on the merits of his life, his achievements. I write because I am lucky to have known Kilty, and never let him know I felt that. I write because I wonder how many theatre artists are forgotten – even before they pass away – and how many may never be given a final bow when they leave us? I am thinking, even now, of others who were kind and generous to me as I began my career, and how I don’t wish to only do them honor when they pass, but to reconnect with them while I, and they, are still able. I think about how, as I grow older, these opportunities will become fewer with every passing year, until I find myself hoping that I am, in some small way, remembered.

We know that theatre is an impermanent art form, as closed productions linger only in the pages and digital memories of journalism, and in the minds of those who saw them. The lives of theatre artists are fleeting as well, and we must honor not only the perpetually famous, but those who have committed their lives to this life, with dedication and talent but perhaps without fame, while they live, so their deaths don’t come as a surprise that triggers reveries and regrets, but as the finales of friends, remembered not from years past, but from our own recent present.

Very nice piece. Thanks. I knew of Jerome Kilty but didn’t know him. When I read his obituary in the Times, I too, wondered how many people might know or remember him. Our theatrical history is an important part of theatre and I’m glad you took the time to remember someone who should be remembered.

While at Harvard, Kilty ’49 placed an ad in The Harvard Crimson that invited any veteran to contact him who wanted to start a new theater group as an alternative to existing Harvard drama activities. As a result, several classmates–including Kilty, my husband, Peter Temple, and Albie Marre (who also died recently)–purchased the Brattle Theatre in Harvard Square (Cambridge) and formed a classical repertory theater company producing 60 plays–chiefly Shakespeare, Shaw, Ibsen and Chekhov–some in association with the Theater Guild and other New York producers. While Kilty performed many of the leading roles, the Brattle attracted many luminaries such as Zero Mostel, William Devlin, Nancy Marchand, Nancy Walker. Many years later my husband and I saw Kilty still giving extraordinary performances at the ART and Huntington Theatre in Boston.